Abstract

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are about 22 nucleotides, non-coding RNAs that affect various cellular functions, and play a regulatory role in different organisms including human. Until now, more than 2500 mature miRNAs in human have been discovered and registered, but still lack of information or algorithms to reveal the relations among miRNAs, environmental chemicals and human health. Chemicals in environment affect our health and daily life, and some of them can lead to diseases by inferring biological pathways.

Results

We develop a creditable online web server, ChemiRs, for predicting interactions and relations among miRNAs, chemicals and pathways. The database not only compares gene lists affected by chemicals and miRNAs, but also incorporates curated pathways to identify possible interactions.

Conclusions

Here, we manually retrieved associations of miRNAs and chemicals from biomedical literature. We developed an online system, ChemiRs, which contains miRNAs, diseases, Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms, chemicals, genes, pathways and PubMed IDs. We connected each miRNA to miRBase, and every current gene symbol to HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) for genome annotation. Human pathway information is also provided from KEGG and REACTOME databases. Information about Gene Ontology (GO) is queried from GO Online SQL Environment (GOOSE). With a user-friendly interface, the web application is easy to use. Multiple query results can be easily integrated and exported as report documents in PDF format. Association analysis of miRNAs and chemicals can help us understand the pathogenesis of chemical components. ChemiRs is freely available for public use at http://omics.biol.ntnu.edu.tw/ChemiRs.

Keywords: microRNA, Gene ontology, Chemical, Genomics, Disease

Background

The interactions between genetic factors and environmental factors have critical roles in determining the phenotype of an organism. In recent years, a number of studies have reported that the dysfunctions on microRNA (miRNAs), environmental factors or their interactions have strong effects on phenotypes and even may result in abnormal phenotypes and diseases [1]. Environmental chemicals have been shown to play a critical role in the etiology of many human diseases [2]. Studies have also demonstrated the link between specific miRNAs and aspects of pathogenesis [3]. The fact that a miRNA may regulate hundreds of targets and one gene might be regulated by more than one miRNAs makes the underlying mechanism of miRNA pathogenicity more complex. Many miRNA targets have been computationally predicted, but only a limited number of these were experimentally validated. Although a variety of miRNA target prediction methods are available, resulting lists of candidate target genes identified by these methods often do not overlap and thus show inconsistency. Hence, finding a functional miRNA target is still a challenging task [4]. Some integration methods and tools for comprehensive analysis of miRNA target prediction have been developed, such as miRGen [5], miRWalk [6], starBase [7], and ComiR [8]. However, it is rarely seen the consolidation and comparison of miRNA target prediction methods with chemicals, diseases, pathways and Gene Ontology (GO) related applications. Thus, it is crucial to develop the bioinformatics tools for more accurate prediction as it is equally important to validate the predicted target genes experimentally [9]. In this study, we develop a ChemiRs web server, in which various miRNA prediction methods and biological databases are integrated and relations between miRNAs, chemicals, genes, diseases and pathways are analyzed. First, we manually retrieved the associations of miRNAs and chemicals from biomedical literature, and downloaded toxicogenomics data from the comparative toxicogenomic database (CTD; http://ctd.mdibl.org) [10]. Then, our method integrated the latest versions of publicly available miRNA target prediction methods and curated databases, including DIANA-microT [11, 12], miRanda [13], miRDB [14], RNAhybrid [15], PicTar [16], PITA [17], RNA22 [18], TargetScan [19], miRWalk [6], miRecords [20], miR2Disease [21], and miRBase [22, 23]. A set of experimentally validated target genes integrated from the miRecords and mirTarBase [24] servers is also integrated in the ChemiRs server. In addition, information from KEGG [25], REACTOME [26], and Gene Ontology [27] databases were organized into ChemiRs manually. The logical restriction was also designed to compare different miRNA target prediction methods easily using R (http://www.r-project.org) for statistics.

Implementation

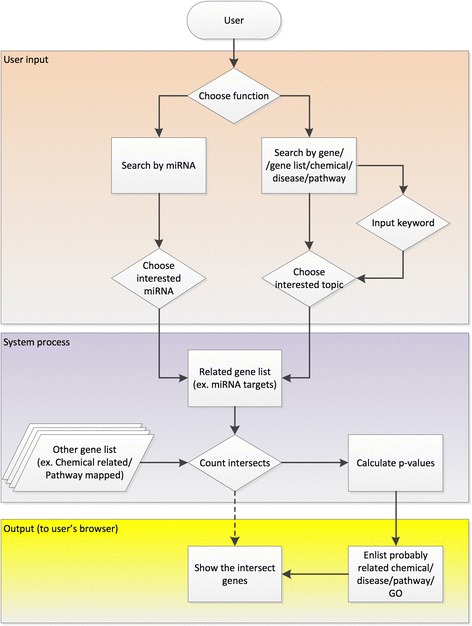

The workflow of ChemiRs server is illustrated in Fig. 1. Given different types of query inputs from the users, ChemiRs server extracts relevant search results from various prediction methods and databases. Then, the results are shown in an interactive viewer and available as downloadable files. Next, the data sources, implementation and components of ChemiRs are described as follows.

Fig. 1.

The workflow of ChemiRs web server. Illustration of six analysis modules provided by ChemiRs

Input

To access ChemiRs web server, a user has to choose a search function from main menu for one or more searches as query processing. In the ‘Search by miRNA’ module, the user directly selects a miRNA of interest from a dropdown list of human miRNAs. For the other search modules (i.e., search by gene, genelist, chemical, disease and pathway), the user can submit a query keyword of interest to search for related topics. A graphical control checkbox permits the user to make multiple choices of both the search databases and topics of interest. Detailed descriptions of the inputs are given by scrollable tabboxes, checkboxes, radio buttons or type text. Then, the ChemiRs server processes the user query, generates the intersection of search results, and calculates the statistical significance level with p-value.

Output

The search results of target genes and related associations with chemicals, diseases, pathways and GO terms are shown in the ChemiRs server. The output results are presented to the user via both an interactive viewer and downloadable files.

Interactive viewer

Query results are shown in a tabbox and automatically made scrollable when the sum of their width exceeds the container width size. The listbox component can automatically generate checkboxes or radio buttons for selecting list items by user selected attributes. Checkboxes allow multiple selections to be made, unlike the radio buttons. It is easy to obtain results immediately with sorting functionalities built in the grid and listbox components.

Downloadable files

The results can also be downloaded as comma-separated value (CSV) files, which can be easily imported into Microsoft Excel. The CSV files include all features calculated by ChemiRs. In addition, a related reference represented by the Pubmed ID is also provided. Multiple query results can also be easily integrated and exported as report documents in PDF format.

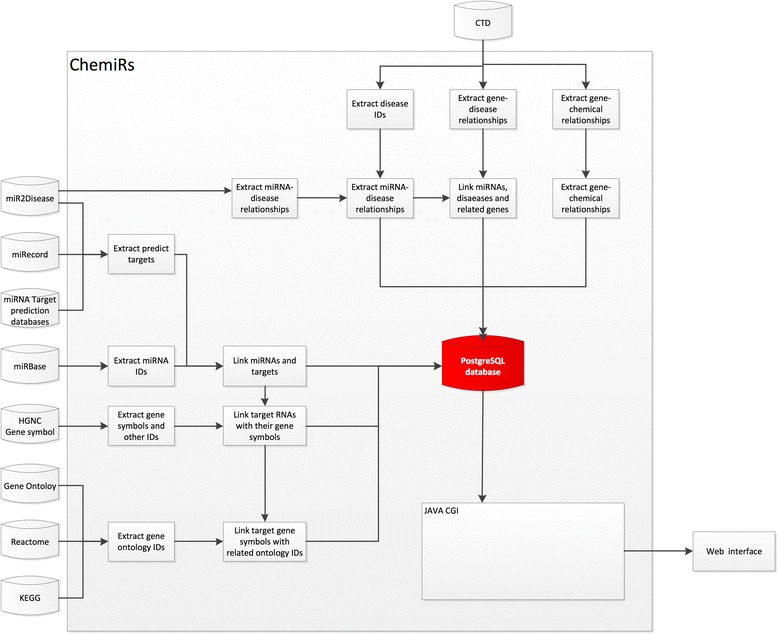

Data sources

Schema of the client-server architecture of ChemiRs is shown in Fig. 2. ChemiRs incorporated miRNA target prediction methods and curated databases, including DIANA-microT, miRanda, miRDB, RNAhybrid, PicTar, PITA, RNA22, TargetScan, miRWalk, miRecords, miR2Disease and miRBase as shown in Table 1. Data from the latest versions of all dependent databases are collected and integrated into a relational database in the ChemiRs server. A set of experimentally validated target genes integrated from the miRecords and mirTarBase servers is also integrated in the ChemiRs server. In addition, biological information from CTD, KEGG, REACTOME and Gene Ontology databases were manually curated into ChemiRs. The information is stored in a remote PostgreSQL server which is accessed through a Java Model-View-Controller (MVC) web service design. MyBatis library is used to connect to databases, and data can be retrieved by clients in both text and PDF formats.

Fig. 2.

System overview of ChemiRs core framework. All results generated by ChemiRs are deposited in PostgreSQL relational databases and displayed in the visual browser and web page

Table 1.

The versions and links of dependent databases used in the ChemiRs server

| Database | Version | Link |

|---|---|---|

| CTD | 2016/2/9 | http://ctdbase.org/ |

| miR2Disease | 2011/3/14 | http://www.mir2disease.org/ |

| miRecords | 2013/4/27 | http://c1.accurascience.com/miRecords/ |

| miRBase | Release 21 | http://www.mirbase.org/ftp.shtml |

| miRWalk | 2011/3/29 | http://zmf.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/apps/zmf/mirwalk/ |

| DIANA-microT | Version 4.0 | http://diana.imis.athena-innovation.gr/DianaTools/index.php?r=microtv4/index |

| miRanda | August 2010 Release | http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do |

| miRDB | Version 5.0 | http://mirdb.org/miRDB/ |

| PicTar(4way) | 2007/3/1 | http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de/cgi-bin/PicTar_vertebrate.cgi |

| PicTar(5way) | 2007/4/1 | http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de/cgi-bin/new_PicTar_vertebrate.cgi |

| TargetScan | Version 6.0 | http://www.targetscan.org/ |

| HGNC | 2016/2/29 | http://www.genenames.org/cgi-bin/statistics |

| miRTarBase | Release 6.0 | http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/index.php |

Results and discussion

Data statistics in ChemiRs

The data statistics of ChemiRs are described in Table 2. All data were organized in ChemiRs.

Table 2.

Data statistics in the ChemiRs server

| Category | Total number |

|---|---|

| Unique miRNAs | 2,588 |

| Unique genes | 36,817 |

| Unique chemicals | 161,394 |

| Unique diseases | 11,860 |

| Unique pathways | 292 |

| Gene Ontology (GO) terms | 41,468 |

| miRNA-target genes associations | 5,087,441 |

| miRNA-disease associations | 2,323 |

| Chemical-gene interactions | 500,105 |

| Gene-disease associations | 182,490 |

| Chemical-disease associations | 1,834,693 |

| Gene-GO annotations | 314,375 |

Case studies

The aim of ChemiRs web server is to provide integrated and comprehensive miRNA target prediction analysis via flexible search functions, including search by miRNAs, gene lists, chemicals, genes, diseases and pathways. Next, case study examples by six different search methods are described in the following sections.

Search by a miRNA

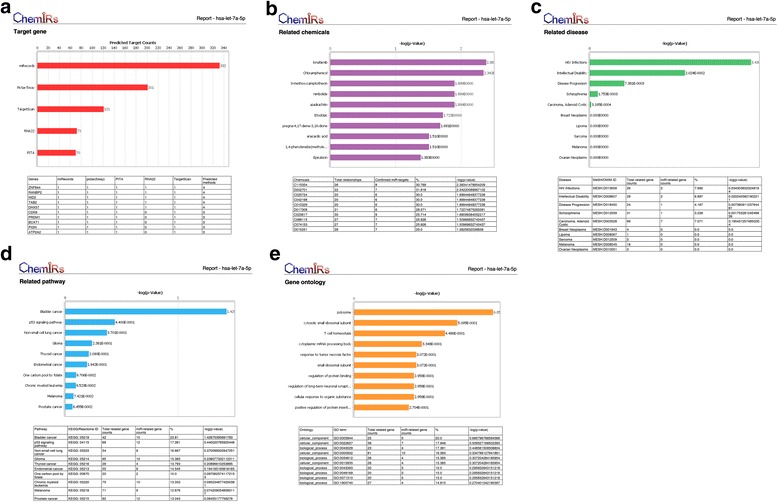

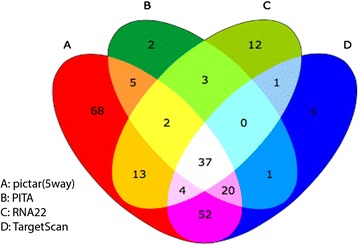

As an example, we applied ChemiRs to analyze the hsa-let-7a-5p miRNA. We selected the miRNA ‘hsa-let-7a-5p’ in ‘Search by miRNA’ module and chose ‘pictar(5way),’ ‘PITA,’ ‘RNA22,’ and ‘TargetScan’ as miRNA target prediction methods; ‘4 minimum predicted methods’ as restrictions; and ‘Targets,’ ‘Chemicals,’ ‘Diseases,’ ‘Pathways,’ and ‘GO terms’ as the output functions, respectively. This example can be referred by clicking ‘Tip#2 logical analysis’ on the start page of ChemiRs. As shown in Fig. 3, a PDF report including top ten results can be easily downloaded. We checked ‘target genes,’ the top ten ‘related chemicals,’ ‘related diseases,’ ‘related pathways,’ and ‘related GO terms’ returned by ChemiRs, which were sorted according to their significance of activity changes denoted by -log(p-value). The p-value represents the probability of a random intersection of two different gene sets, and the p-value calculations are based on hypergeometric distribution. The probability to randomly obtain an intersection of certain size between user’s set and a network/pathway follows hypergeometric distribution. The lower the p-value, the higher is the non-randomness of finding such intersection. By taking log of p-value, the higher the -log(p-value), the higher is the non-randomness. Generally, when p-value is considered as 0.05, the -log(p-value) greater than 2.995 denotes statistically significant. As shown in Fig. 4, our system identified 37 miRNAs within the intersection of the 4-way Venn diagram. Notably, the top one related pathway, ‘Bladder cancer,’ has already been reported to be associated with the hsa-let-7a miRNA in biomedical literature [28]. This demonstrates that our proposed method is able to identify important features that correspond well with biological insights.

Fig. 3.

Query result of ‘hsa-let-7a-5p’ by ‘Search by miRNA’ module in ChemiRs. Given a miRNA as query, ChemiRs identifies related a Targets, b Chemicals, c Diseases, d Pathways and e GO terms as output, respectively

Fig. 4.

The four-way Venn diagram of hsa-let-7a-5p target genes using a pictar(5way), b PITA, c RNA22 and d TargetScan as the miRNA target prediction methods in ChemiRs

Search by a gene list

We applied ChemiRs to analyze a gene list data reported by Naciff et al. [29], in which the gene set was selected according to expression changes induced by Bisphenol A (BPA) and 17alpha-ethynyl estradiol in human Ishikawa cells. We downloaded the gene list with 76 genes in Table 6 [29] under the accession number GSE17624. We used the 76 genes gene symbols as input in ChemiRs by choosing ‘Search by gene list’ module, and ‘miRNAs,’ ‘Chemicals,’ ‘Diseases,’ ‘Pathways,’ and ‘GO terms’ as the output functions; all ten methods as miRNA target prediction methods; and ‘5 minimum predicted methods’ as restrictions, respectively.

We analyzed the top ten related chemicals returned by ChemiRs, which were sorted according to their significance of activity changes (i.e., −log(p-value)). Interestingly, we found that these chemicals have already been well-known to be associated with estrogens or Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs). In fact, many industrially made estrogenic compounds and other EDCs are potential risk factors of cancer. Moreover, estrogen and progesterone receptor status have already been reported to be associated with breast cancer [30]. For example, BPA was linked to breast cancer tumor growth [31]. It is expected that other chemicals might also be involved in ‘Pathways in cancer’ returned by ChemiRs, and these chemicals might be potential candidates for further investigation.

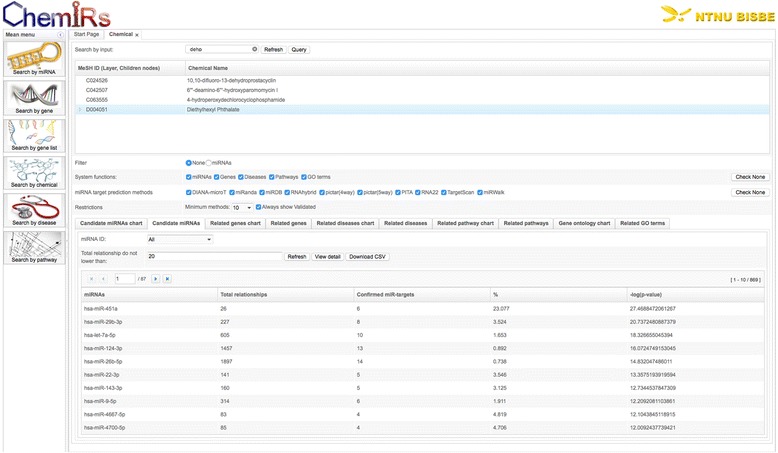

Search by a chemical

Here, we exemplify the application of ChemiRs to search by chemicals. We applied ChemiRs to analyze diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) by submitting ‘DEHP’ in ‘Search by chemical’ module. After pressing the ‘Refresh’ button, we clicked the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) ID ‘D004051, Diethylhexyl Phthalate’ and chose ‘None’ as the filter; ‘miRNAs,’ ‘Genes,’ ‘Diseases,’ ‘Pathways,’ and ‘GO terms’ as the output functions; all ten methods as miRNA target prediction methods, and ‘10 minimum predicted methods’ as restrictions, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5, the results can be easily downloaded as CSV files.

Fig. 5.

Query result of ‘DEHP’ by ‘Search by chemical’ module in ChemiRs. Related miRNAs of MeSH ID ‘D004051, Diethylhexyl Phthalate’ are listed

We checked ‘Candidate miRNAs,’ the top ten ‘related genes,’ ‘related diseases,’ ‘related pathways,’ and ‘related GO terms’ returned by ChemiRs, which were sorted according to their significance of activity changes (i.e., −log(p-value)). The 93 related human genes and their associated references are listed in Table 3. The top one related pathway is ‘Pathways in cancer,’ and the top one related disease is ‘Brest-Ovarian Cancer, Familiar, Susceptibility To, 1; BROVCA1 (OMIM: 604370).’ DEHP is converted by intestinal lipases to mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), which is then preferentially absorbed [2]. It has already been reported that exposure to the parent compound of the phthalate metabolite MEHP might be associated with breast cancer [32].

Table 3.

Ninety-three related human genes and associated PubMed references of searching by chemical for MeSH ID (D004051, Diethylhexyl Phthalate)

| Gene | Chemical | Reference PubMed ID |

|---|---|---|

| NR1I2 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 23899473;16054614;11581012;22206814;17003290;21227907 |

| PPARG | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 21561829;10581215;16326050;12927354;23118965 |

| PPARA | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 10581215;20123618;21354252;16455614 |

| CYP3A4 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23545481;18332045;22186153 |

| CYP19A1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22401849;19501113;19822197 |

| ESR1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 20382090;16756374;15840436 |

| CYP3A4 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 11581012;18332045;21742782 |

| CASP3 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 22155658;23220035;21864672 |

| CASP3 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 12927354;19165384;23360888 |

| PPARA | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 10581215;20123618;16326050 |

| CYP1A1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 8242868;16954067 |

| NR1I3 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 21227907;23899473 |

| NR4A1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23118965;19822197 |

| CYP2C9 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22186153;23545481 |

| AR | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 19643168;20943248 |

| AKR1B1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 20943248;19643168 |

| AKT1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 19956873;23793038 |

| IL4 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 20082445 |

| HEXB | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 20082445 |

| HEXA | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 20082445 |

| ESR2 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 15840436 |

| CYP1B1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 16040568 |

| CXCL8 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 23724284 |

| CDO1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 16223563 |

| CASP9 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 22155658 |

| CASP8 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 22155658 |

| CASP7 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 21864672 |

| BCL2 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 22155658 |

| BAX | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 22155658 |

| AHR | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 23220035 |

| ACADVL | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 21354252 |

| ACADM | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 21354252 |

| ABCB1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 17003290 |

| ZNF461 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 19822197 |

| VCL | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| TXNRD1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23360888 |

| TP53 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 21515331 |

| STAR | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22401849 |

| SREBF2 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23118965 |

| SREBF1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23118965 |

| SQLE | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23118965 |

| SLC22A5 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23118965 |

| SCD | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23118965 |

| SCARA3 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23360888 |

| PTGS2 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23360888 |

| PRNP | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23360888 |

| PPARGC1A | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 20123618 |

| NR4A3 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 19822197 |

| NR4A2 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 19822197 |

| NR1I2 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 16054614 |

| NR1H3 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23118965 |

| NCOR1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 20123618 |

| MYC | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| MMP2 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| MED1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 20123618 |

| MBD4 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 20123618 |

| MARS | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| LHCGR | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22401849 |

| LFNG | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| IL17RD | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| ID1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| HSD11B2 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 19786001 |

| HMGCR | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23118965 |

| GUCY2C | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22401849 |

| GLRX2 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23360888 |

| GJA1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| FSHR | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22401849 |

| FSHB | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 19501113 |

| FASN | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23118965 |

| EP300 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 20123618 |

| DHCR24 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23360888 |

| DDIT3 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| CYP2C19 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22186153 |

| CYP1A1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 15521013 |

| CTNNB1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| CSNK1A1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 16484285 |

| CLDN6 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22321834 |

| CGB | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 22461451 |

| CGA | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 19501113 |

| CELSR2 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 16484285 |

| CDKN1A | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 21515331 |

| CASP7 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23360888 |

| BCL2 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 12927354 |

| BAX | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 12927354 |

| AOX1 | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 23360888 |

| VEGFA | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 18252963 |

| AMH | mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 19165384 |

| TNF | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 20082445 |

| TIMP2 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 19956873 |

| SUOX | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 16223563 |

| RPS6KB1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 23793038 |

| PPARD | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 16455614 |

| PIK3CA | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 23793038 |

| PAPSS2 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 16223563 |

| PAPSS1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 16223563 |

| NCOA1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 11581012 |

| MYC | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 16455614 |

| MTOR | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 23793038 |

| MMP9 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 19956873 |

| MMP2 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 19956873 |

| MAPK3 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 16455614 |

| MAPK1 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 16455614 |

| LAMP3 | Diethylhexyl Phthalate | 20678512 |

Search by a gene

We applied ChemiRs to analyze the CXCR4 gene using ‘Search by gene’ module. After pressing the ‘Refresh’ button, we clicked ‘CXCR4,’ chose all output system functions, and pressed the ‘Query’ button. All the ‘related miRNAs,’ ‘related chemicals,’ ‘related diseases,’ ‘related pathways,’ and ‘related GO terms’ will be returned by ChemiRs.

Search by a disease

We applied ChemiRs to analyze Schizophrenia in ‘Search by disease’ module. We used ‘Schizophrenia’ as query and pressed the ‘Refresh’ button. A simple tree data model is used to represent a disease tree, and we pressed the light blue line’MeSH: D012559 Schizophrenia.’ All disease annotations included ‘MeSH Heading’ (i.e., controlled term in the MeSH thesaurus), ‘Tree Number’ (i.e., tree number of the MeSH term), ‘Scope Note’ (i.e., the scope notes that define the subject heading), and ‘MeSH Tree Structures’ (i.e., tree structure of the MeSH term) will be returned by ChemiRs.

Search by a pathway

We applied ChemiRs to analyze a cell cycle pathway using ‘Search by pathway’ module. We entered ‘cell cycle’ and pressed the ‘Refresh’ button, then five relevant pathways are listed. After we pressed the light blue line ‘KEGG: 04110 Cell cycle,’ all the hsa04110 pathway information will be returned.

Future extensions

In the future, we will continuously develop and enhance the interactive analysis module and adjust the web service for better user-experience. An automatic update will also be carried out monthly to keep pace with the latest database versions. It is also planned to incorporate more applications for gene expression data and allow users to customize their own visualization.

Conclusion

The ChemiRs web server integrates and compares ten miRNA target prediction methods of interest. The server provides comprehensive features to facilitate both experimental and computational target predictions. In addition, ChemiRs incorporates flexible search modules including (i) search by miRNA, (ii) search by gene, (iii) search by gene list, (iv) search by chemical, (v) search by disease and (vi) search by pathway. Moreover, ChemiRs can make predictions for Homo sapiens miRNAs of interest, and also allow fast search of query results for multiple miRNA selection and logical restriction, which can be easily integrated and exported as report documents in PDF format. The service is unique in that it integrates a large number of miRNA target prediction methods, experiment results, genes, chemicals, diseases and GO terms with instant and visualization functionalities.

Availability and requirements

Home page: http://omics.biol.ntnu.edu.tw

Tip: http://omics.biol.ntnu.edu.tw: Welcome

Demo: http://omics.biol.ntnu.edu.tw: Video

Tutorial: http://omics.biol.ntnu.edu.tw: Help

Operating system(s): Both portal and clients are platform independent.

Programming language: JAVA, JavaScript

Any restrictions to use by non-academics: None

Acknowledgements

We thank the NTNU BISBE Lab for supporting computational resources for this work.

Abbreviations

- BPA

bisphenol A

- DEHP

diethylhexyl phthalate

- GO

gene ontology

- MEHP

mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate

- MeSH

medical subject heading

- miRNA

microRNA

- MVC

Model-View-Controller

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SS and YCT initiated the study; YSC, YCT and JL implemented the system; SS, BCH and SLU tested the software; ECYS and SS wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Emily Chia-Yu Su, Email: emilysu@tmu.edu.tw.

Yu-Sing Chen, Email: 40043208s@ntnu.edu.tw.

Yun-Cheng Tien, Email: 495432294@ntnu.edu.tw.

Jeff Liu, Email: jeffliu@caece.net.

Bing-Ching Ho, Email: f94424002@ntu.edu.tw.

Sung-Liang Yu, Email: slyu@ntu.edu.tw.

Sher Singh, Email: sher@ntnu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Yang Q, Qiu C, Yang J, Wu Q, Cui Q. miREnvironment database: providing a bridge for microRNAs, environmental factors and phenotypes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(23):3329–30. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh S, Li SS. Phthalates: toxicogenomics and inferred human diseases. Genomics. 2011;97(3):148–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latronico MV, Catalucci D, Condorelli G. MicroRNA and cardiac pathologies. Physiol Genomics. 2008;34(3):239–42. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90254.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witkos TM, Koscianska E, Krzyzosiak WJ. Practical Aspects of microRNA Target Prediction. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11(2):93–109. doi: 10.2174/156652411794859250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Megraw M, Sethupathy P, Corda B, Hatzigeorgiou AG. miRGen: a database for the study of animal microRNA genomic organization and function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D149–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dweep H, Sticht C, Pandey P, Gretz N. miRWalk--database: prediction of possible miRNA binding sites by “walking” the genes of three genomes. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(5):839–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang JH, Li JH, Shao P, Zhou H, Chen YQ, Qu LH. starBase: a database for exploring microRNA-mRNA interaction maps from Argonaute CLIP-Seq and Degradome-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D202–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coronnello C, Benos PV. ComiR: Combinatorial microRNA target prediction tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Web Server issue):W159–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekimler S, Sahin K. Computational Methods for MicroRNA Target Prediction. Genes. 2014;5(3):671–83. doi: 10.3390/genes5030671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis AP, Grondin CJ, Lennon-Hopkins K, Saraceni-Richards C, Sciaky D, King BL, Wiegers TC, Mattingly CJ. The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database's 10th year anniversary: update 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D914–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Maragkakis M, Reczko M, Simossis VA, Alexiou P, Papadopoulos GL, Dalamagas T, Giannopoulos G, Goumas G, Koukis E, Kourtis K, et al. DIANA-microT web server: elucidating microRNA functions through target prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W273–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Maragkakis M, Vergoulis T, Alexiou P, Reczko M, Plomaritou K, Gousis M, Kourtis K, Koziris N, Dalamagas T, Hatzigeorgiou AG. DIANA-microT Web server upgrade supports Fly and Worm miRNA target prediction and bibliographic miRNA to disease association. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39(Web Server issue):W145–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(11):e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X. miRDB: a microRNA target prediction and functional annotation database with a wiki interface. RNA. 2008;14(6):1012–7. doi: 10.1261/rna.965408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruger J, Rehmsmeier M. RNAhybrid: microRNA target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W451–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37(5):495–500. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Kertesz M, Iovino N, Unnerstall U, Gaul U, Segal E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat Genet. 2007;39(10):1278–84. doi: 10.1038/ng2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miranda KC, Huynh T, Tay Y, Ang YS, Tam WL, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. A pattern-based method for the identification of MicroRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006;126(6):1203–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao F, Zuo Z, Cai G, Kang S, Gao X, Li T. miRecords: an integrated resource for microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D105–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang Q, Wang Y, Hao Y, Juan L, Teng M, Zhang X, Li M, Wang G, Liu Y. miR2Disease: a manually curated database for microRNA deregulation in human disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D154–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D152–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou CH, Chang NW, Shrestha S, Hsu SD, Lin YL, Lee WH, Yang CD, Hong HC, Wei TY, Tu SJ, et al. miRTarBase 2016: updates to the experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D239–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D199–205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Croft D, Mundo AF, Haw R, Milacic M, Weiser J, Wu G, Caudy M, Garapati P, Gillespie M, Kamdar MR, et al. The Reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D472–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Li Y, Liu H, Lai C, Du X, Su Z, Gao S. The Lin28/let-7a/c-Myc pathway plays a role in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;354(2):533–41. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1715-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naciff JM, Khambatta ZS, Reichling TD, Carr GJ, Tiesman JP, Singleton DW, Khan SA, Daston GP. The genomic response of Ishikawa cells to bisphenol A exposure is dose- and time-dependent. Toxicology. 2010;270(2–3):137–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Setiawan VW, Monroe KR, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN, Pike MC, Henderson BE. Breast cancer risk factors defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status: the multiethnic cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(10):1251–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhan A, Hussain I, Ansari KI, Bobzean SA, Perrotti LI, Mandal SS. Bisphenol-A and diethylstilbestrol exposure induces the expression of breast cancer associated long noncoding RNA HOTAIR in vitro and in vivo. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;141:160–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmes AK, Koller KR, Kieszak SM, Sjodin A, Calafat AM, Sacco FD, Varner DW, Lanier AP, Rubin CH. Case-control study of breast cancer and exposure to synthetic environmental chemicals among Alaska Native women. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2014;73:25760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]