Abstract

Background

Surviving expression might serve as a prognostic biomarker predicting the clinical outcome of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The study was conducted to explore the potential correlation of survivin protein expression with NSCLC and its clinicopathologic characteristics.

Methods

PubMed, Medline, Cochrane Library, CNKI and Wanfang database were searched through January 2016 with a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data was extracted from these articles and all statistical analysis was conducted by using Stata 12.0.

Results

A total of 28 literatures (14 studies in Chinese and 14 studies in English) were enrolled in this meta-analysis, including 3206 NSCLC patients and 816 normal controls. The result of meta-analysis demonstrated a significant difference of survivin positive expression between NSCLC patients and normal controls (RR = 7.16, 95 % CI = 4.63-11.07, P < 0.001). To investigate the relationship of survivin expression and clinicopathologic characteristics, we performed a meta-analysis in NSCLC patients. Our results indicates survivin expression was associated with histological differentiation, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage and lymph node metastasis (LNM) (RR = 0.80, 95 % CI = 0.73-0.87, P < 0.001; RR = 0.75, 95 % CI = 0.67-0.84, P < 0.001; RR = 1.14, 95 % CI = 1.01-1.29, P = 0.035, respectively), but not pathological type and tumor size. (RR = 1.00, 95 % CI = 0.93-1.07, P = 0.983; RR = 0.95, 95 % CI = 0.86-1.05, P = 0.336, respectively).

Conclusion

Higher expression of survivin in NSCLC patients was found when compared to normal controls. Survivin expression was associated with the clinicopathologic characteristics of NSCLC and may serves as an important biomarker for NSCLC progression.

Keywords: Survivin, Non-small cell lung cancer, Pathological characteristics, Meta-Analysis

Background

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains one of the most fatal health problems in terms of morbidity and mortality and is the leading cause of cancer-related mortalities worldwide [1]. Histologically, NSCLC is consisted of three different subtypes: squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large cell carcinoma, accounting for approximately 80 % ~ 85 % of lung cancer [2]. NSCLC is highly resistant to the existing cancer therapeutics and the great majority of NSCLC patients are diagnosed at advanced tumor stage. Although the recent advances in clinical and experimental oncology the survival of advanced NSCLC are still poor, with a 5-year survival rate of about 15 % [3, 4].

It is generally accepted that abnormal inhibition of apoptosis during homeostasis plays an important role in cancer development, progression and resistance to therapy [5]. Survivin, the common member of the inhibitor of the apoptosis protein (IAP) family, is a protein encoded by the BIRC5 gene in human with dual role in promoting cell proliferation and preventing apoptosis [6]. Previous studies revealed that survivin expression was found in precancerous lesions as well as in early stages of cancer in the skin, uterine cervix, colon, and oral mucosa [7, 8]. It was reported that survivin expression might serve as a prognostic biomarker predicting the clinical outcome of NSCLC, and might be associated with the clinicopathologic characteristics of NSCLC [5]. Perobska I et al. showed that lymph node metastases, tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage and tumor size had a higher incidence of survivin expression [9]. In order to clarify the relation between survivin expression and NSCLC, we conducted this meta-analysis.

Methods

Publication search

Online electronic databases (PubMed, Medline, Cochrane Library, CNKI and Wanfang) were searched with the key terms: (survivin or survivin protein) and (non-small cell lung cancer or NSCLC or non-small-cell lung carcinoma) (update to January 2016). We also checked out the reference lists of all retrieved studies and relevant reviews manually for important cross-references.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Published studies were selected if they met all of the following criteria: (1) The study must be conducted in NSCLC patients; (2) The study must evaluate the Survivin protein expression; (3) Sufficient data, especially survivin positive expression in NSCLC patients and normal controls, have been provided to calculate risk ratios (RR) and 95 % confidence interval (95 % CI); (4) Number of NSCLC cases in enrolled studies should be more than 60; (5) The study must be published in a peer-reviewed journal; (6) The study must be independent from other studies. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The studies did not conform to the inclusion criteria; (2) Reviews, case reports, editorials, guidelines and comments were excluded; (3) In case of duplicated publications or studies with overlapping data, the study with largest data was selected.

Data extraction and qualitative assessment

The following data were collected from all the included studies: first author, publication year, country, ethnicity of participants, language, and numbers of participants, age, gender, subcellular localization and positive expression of survivin. Data from the finally selected studies were extracted based on a standard protocol. Potential discrepancy was resolved by discussions or by consulting the original report. Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of the included trials using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) criteria to ensure consistency in reviewing and reporting results. The studies were scored based on three aspects: (1) selection of study group; (2) comparability of study groups; (3) ascertainment of the outcome of interest. A study was considered as low, moderate or high quality with the score 0 ~ 3, 4 ~ 6 and 7 ~ 9, respectively. Disagreement was settled by discussion, or a third investigator was consulted.

Statistical analysis

Statistical test was conducted with the STATA statistical software (Version 12.0, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). To assess the correlation between survivin protein expression and the clinicopathologic characteristics, RR and its 95 % CI were calculated using random effects model or fixed-effects model. The statistical significance of pooled RRs was estimated by the application of Z test. We used Cochran’s Q-statistic (P < 0.05 was considered significant) and I2 test to assess heterogeneity among studies. Random effects model was applied for the evidence of significant heterogeneity (P < 0.05 or I2 test exhibited > 50 %); otherwise, fixed-effects model was used. Univariate and multivariate meta-regression analyses were used to evaluate the potential sources of heterogeneity. Further identification was performed by using Monte Carlo method. Additionally, we applied a sensitivity analysis to evaluate whether one single study had the weight to impact on the overall estimate. Further, the effect of publication bias was examined by Egger’s linear regression test (P < 0.05 was considered significant).

Results

Literature searching results and baseline characteristics of included studies

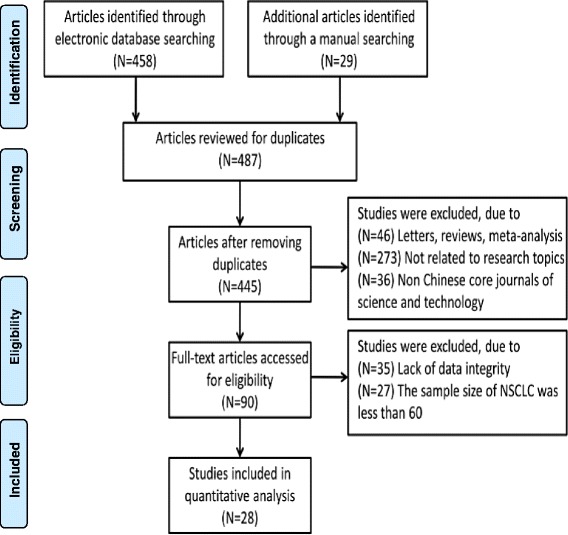

Four hundred and eighty-seven articles were initially identified through database searches. Twenty-eight studies remained after excluding duplicates (n = 42), letters, reviews, meta-analyses (n = 46) and irrelevant topic (n = 273), non-core journal in Chinese (n = 36), insufficient information in studies (n = 35) and number of NSCLC cases less than 60 (n = 27), 28 trials were finally selected for this meta-analysis (Fig. 1) [5, 10–36]. The enrolled studies published between 2005 and 2015 included 3206 NSCLC patients and 816 normal controls, with 2252 males and 954 females. For the pathological type, 1010 patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 806 with adenocarcinoma (AC). With respect to clinicopathologic features, 1198 patients with well/moderate differentiation, 788 with poor differentiation; 1421 at I/II stage and 1009 at III/IV stage (TNM stage); 1256 patients with lymphatic metastasis and 1185 patients without lymphatic metastasis. All included studies scored 7 in terms of NOS scores. The baseline characteristics of included studies were showed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow chart of study selection procedure

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies

| First author | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Language | Disease | Method | Case Number | Sample source | Gender (M/F) | Age (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hirano H | 2015 | Japan | Asians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 157 | tissue | 115/42 | 66.7(47–82) |

| Hu S | 2013 | China | Asians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 256 | tissue | 176/80 | 57.7 |

| Sun PL | 2013 | Korea | Asians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 373 | tissue | 258/115 | 65.0(21–84) |

| Zhang XY | 2012 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(SP) | 60 | tissue | 35/25 | 54.0(30–78) |

| Peng X | 2012 | China | Asians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 97 | tissue | 75/22 | 58.3(28–75) |

| Wang M | 2012 | China | Asians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 210 | tissue | 130/80 | 59.8(35–76) |

| Gao Q | 2012 | China | Asians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 62 | tissue | 44/18 | 57.8(35–78) |

| Hu FQ | 2011 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(Envision) | 116 | tissue | 78/38 | 65.8(35–84) |

| Guosheng L | 2011 | China | Asians | English | NSCLC | IHC(SP) | 100 | tissue | 69/31 | 55.6(37–76) |

| Fan CF | 2011 | China | Asians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 76 | tissue | 46/30 | 57.1(26–78) |

| Zhu CZ | 2010 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(SP) | 60 | tissue | 39/21 | 62.1(33–78) |

| Yang DX | 2010 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(PowerVision) | 60 | tissue | 40/20 | 53.5(37–71) |

| Zeng ZH | 2010 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC | 60 | tissue | 38/22 | 65.7(40–78) |

| Porebska I | 2010 | Poland | Caucasians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 74 | tissue | 49/25 | 60.5(43–77) |

| Chen YQ | 2009 | China | Asians | English | NSCLC | IHC(SP) | 120 | tissue | 94/26 | 61.0(42–76) |

| Li CH | 2008 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(PV) | 91 | tissue | 77/14 | 62.0(39–78) |

| Shi M | 2007 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC | 80 | tissue | 55/25 | 56.2(33–79) |

| Miao LJ | 2007 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(SP) | 80 | tissue | 53/27 | 58.8(18–78) |

| Xue ZX | 2006 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(SP) | 84 | tissue | 51/33 | 53.2(22–75) |

| Wang M | 2006 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC | 72 | tissue | 45/27 | 58.5(38–74) |

| Li XC | 2006 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(SABC) | 64 | tissue | 41/23 | 55.6(35–78) |

| Yoo J | 2006 | Korea | Asians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 219 | tissue | 168/51 | 65.8 ± 9.9 |

| Huo XD | 2006 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(Envision) | 117 | tissue | 85/32 | 57.5(29–71) |

| Vischioni B | 2006 | Netherlands | Caucasians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 160 | tissue | 129/31 | 64.0(40–86) |

| Akyurek N | 2006 | Turkey | Caucasians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 78 | tissue | 72/6 | 60.8(39–78) |

| Ren YJ | 2006 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(Envision) | 61 | tissue | 45/16 | 62.0(40–75) |

| Qiu HL | 2005 | China | Asians | Chinese | NSCLC | IHC(SP) | 75 | tissue | 51/24 | 57.1 ± 10.6 |

| Shinohara ET | 2005 | America | Caucasians | English | NSCLC | IHC | 144 | tissue | 94/50 | 65.4 ± 11.04 |

(Notes: NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; IHC = Immunohistochemical;M = male; F = female; OA = osteoarthritis)

The comparison between NSCLC patients and normal controls on survivin protein expression

A total of 19 studies provided data of survivin expression in NSCLC patients and normal controls (1537 NSCLC patients and 816 normal controls). Heterogeneity test revealed the existence of heterogeneity in those 19 trials, thus a random-effect model was used (I2 = 58.1 %, P < 0.001). Meta-analysis result revealed that survivin expression in NSCLC patients was significantly higher when compared with normal controls (RR = 7.16, 95 % CI = 4.63-11.07, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots for the comparisons of survivin expression between NSCLC patients and normal controls

The analysis of survivin expression and clinicopathologic characteristics of NSCLC

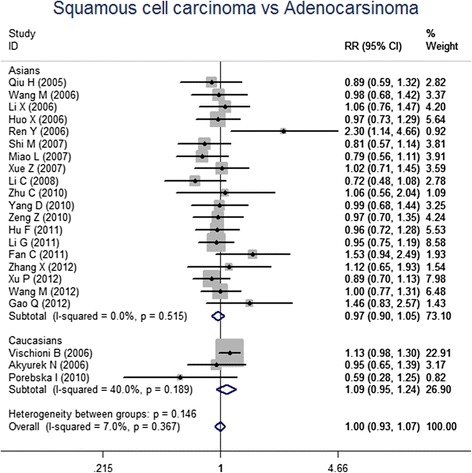

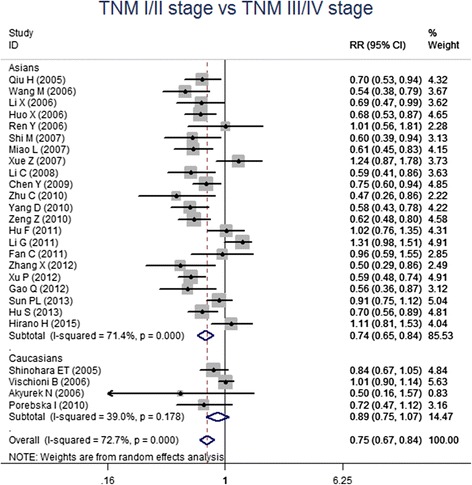

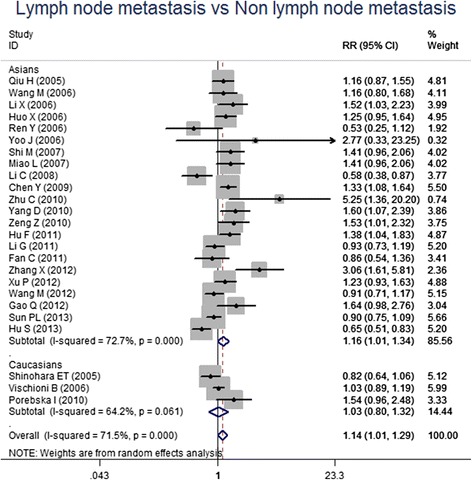

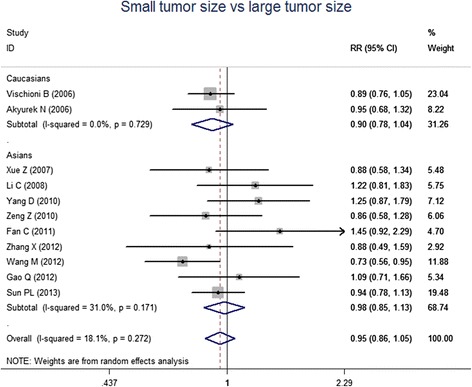

For the meta-analysis according to pathological types, we included 22 studies, involving 1010 SCC patients and 806 AC patients. Heterogeneity test revealed the lack of heterogeneity in these studies and a fixed-effect model was applied (I2 = 7 %, P = 0.367). No significantly different survivin expression was found between squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma (AC) (RR = 1.00, 95 % CI = 0.93-1.07, P = 0.983) (Fig. 3). A total of 21 studies investigated histological differentiation of NSCLC patients and moderate heterogeneity existed in these studies (I2 = 45.4 %, P = 0.013). Results from random-effect model suggested that survivin expression was significantly lower in NSCLC patients with well/moderate differentiation than that in the patients with poor differentiation (RR = 0.80, 95 % CI = 0.73-0.87, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). 26 studies provided survivin expression level at different TNM stages. Heterogeneity test showed the presence of heterogeneity in these studies (I2 = 72.7 %, P < 0.001). Meta-analysis results revealed that NSCLC patients at TNM III/IV stage had a significantly higher survivin expression than the patients at TNM I/II stage (RR = 0.75, 95 % CI = 0.67-0.84, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). A total of 25 studies indicated the status of lymphatic metastasis. Meta-analysis suggested that survivin expression in NSCLC patients with lymphatic metastasis was significantly higher than that in the patients without lymphatic metastasis (RR = 1.14, 95 % CI = 1.01-1.29, P = 0.035) (Fig. 6). 11 studies showed the survivin expression in the patient with different tumor size. No heterogeneity was found in these studies (I2 = 18.1 %, P = 0.272). Meta-analysis revealed that survivin expression was not associated with tumor size (RR = 0.95, 95 % CI = 0.86-1.05, P = 0.336) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots for the comparisons of survivin expression between SCC patients and AC patients

Fig. 4.

Forest plots for the comparisons of survivin expression between well/moderated differentiated patients and poor differentiated patient

Fig. 5.

Forest plots for the comparisons of survivin expression between patients at TNM I/II stage and TNM III/IV stage

Fig. 6.

Forest plots for the comparisons of survivin expression between patients with LNM and without LNM

Fig. 7.

Forest plots for the correlation of survivin expression and tumor size

We also performed subgroup analysis according to the ethnicity. And the results showed survivin expression was associated with respect to histological differentiation, TNM stage and lymph node metastasis in Asian populations but not in Caucasian populations. (Table 2) For Caucasians, only the contrast of NSCLC versus and normal control reach the statistical significance. According to the definition of positive expression, the studies were divided in to 3 subgroups. (1 Survivin expressed in cytoplasm only, 2 Survivin expressed in cytoplasm or nucleus, 3 Survivin expressed in both cytoplasm and nucleus) Subgroup analysis found survivin expression was associated with histological differentiation, TNM stage and lymph node metastasis in subgroup 1 and subgroup 2, but not in subgroup 3. (Table 3)

Table 2.

Summary of subgroup analysis by ethnicity

| Studies | Ethnicity (n) | Studies (n) | Combined RR (95 % CI) | P(Z) | I2 | P(Q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSCLC vs. Control | All | 19 | 7.16(4.63-11.07) | <0.001 | 58.1 % | 0.001 |

| Asians | 18 | 6.60(4.33-10.05) | <0.001 | 55..4 % | 0.002 | |

| Caucasians | 1 | 101(6.34-1608) | 0.001 | / | / | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma vs. Adenocarcinoma | All | 22 | 1.00(0.93, 1.07) | 0.983 | 7.0 % | 0.367 |

| Asians | 19 | 0.97(0.90-1.05) | 0.44 | 0 % | 0.189 | |

| Caucasians | 3 | 1.01(0.78-1.30) | 0.959 | 40.0 % | 0.515 | |

| Well/Moderately differentiated vs. Poor differentiated | All | 21 | 0.80(0.73-0.87) | <0.001 | 45.4 % | 0.013 |

| Asians | 20 | 0.78(0.72-0.86) | <0.001 | 33 % | 0.077 | |

| Caucasians | 1 | 0.96(0.86-1.08) | 0.487 | / | / | |

| TNMI/II stage vs. TNM III/IVstage | All | 26 | 0.75(0.67-0.84) | <0.001 | 72.7 % | <0.001 |

| Asians | 22 | 0.74(0.65-0.84) | <0.001 | 71.4 % | <0.001 | |

| Caucasians | 4 | 0.89(0.75-1.07) | 0.222 | 39 % | 0.178 | |

| Lymph node metastasis vs. Non lymph node metastasis | All | 25 | 1.14(1.01-1.29) | 0.035 | 71.5 % | <0.001 |

| Asians | 22 | 1.16(1.01-1.34) | 0.037 | 72.7 % | <0.001 | |

| Caucasians | 3 | 1.03(0.80-1.32) | 0.839 | 64.2 % | 0.061 | |

| Small Tumor vs. Big Tumor | All | 11 | 0.95(0.86-1.05) | 0.336 | 18.1 % | 0.272 |

| Asians | 9 | 0.98(0.85-1.13) | 0.796 | 31 % | 0.171 | |

| Caucasians | 2 | 0.90(0.78-1.04) | 0.161 | 0 % | 0.729 |

Table 3.

Summary of subgroup analysis by localization of survivin expression

| Contrasts | Subcellular locolization | Study (n) | Combined RR (95 % CI) | P(Z) | I2 | P(Q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSCLC vs. Control | All | 19 | 7.16(4.63-11.07) | <0.001 | 58.1 % | 0.001 |

| Cytoplasma | 9 | 7.14(4.19-12.16) | <0.001 | 43.8 % | 0.076 | |

| Cytoplasma or nuclearus | 5 | 3.96(1.93-8.14) | <0.001 | 46.1 % | 0.115 | |

| Cytoplasma and nuclearus | 2 | 17.41(1.2-252.4) | 0.036 | 70.5 % | 0.065 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma vs. Adenocarcinoma | All | 22 | 0.99(0.92, 1.07) | 0.866 | 7.0 % | 0.367 |

| Cytoplasma | 11 | 0.98(0.88-1.08) | 0.641 | 0 % | 0.767 | |

| Cytoplasma or nuclearus | 6 | 0.98(0.83-1.15) | 0.771 | 30.8 % | 0.204 | |

| Cytoplasma and nuclearus | 2 | 1.74(1.12-2.71) | 0.013 | 0 % | 0.324 | |

| Well/Moderately differentiated vs. Poor differentiated | All | 21 | 0.80(0.73-0.87) | <0.001 | 45.4 % | 0.013 |

| Cytoplasma | 8 | 0.84(0.75-0.93) | 0.001 | 19.6 % | 0.274 | |

| Cytoplasma or nuclearus | 7 | 0.68(0.52-0.88) | 0.003 | 68.9 % | 0.004 | |

| Cytoplasma and nuclearus | 2 | 0.73(0.46-1.16) | 0.179 | 42.7 % | 0.186 | |

| TNMI/II stage vs. TNM III/IVstage | All | 26 | 0.75(0.67-0.84) | <0.001 | 72.7 % | <0.001 |

| Cytoplasma | 12 | 0.83(0.69-1.01) | 0.059 | 74.1 % | <0.001 | |

| Cytoplasma or nuclearus | 8 | 0.73(0.61-0.88) | 0.001 | 74.5 % | <0.001 | |

| Cytoplasma and nuclearus | 2 | 0.73(0.41-1.29) | 0.278 | 59.7 % | 0.115 | |

| Lymph node metastasis vs. Non lymph node metastasis | All | 25 | 1.14(1.01-1.29) | 0.035 | 71.5 % | <0.001 |

| Cytoplasma | 10 | 1.24(1.07-1.44) | 0.005 | 53.1 % | 0.024 | |

| Cytoplasma or nuclearus | 9 | 1.12(0.89-1.41) | 0.352 | 76.6 % | <0.001 | |

| Cytoplasma and nuclearus | 2 | 0.96(0.32-2.91) | 0.949 | 83.1 % | 0.015 | |

| Small Tumor vs. Big Tumor | All | 11 | 0.95(0.86-1.05) | 0.336 | 18.1 % | 0.272 |

| Cytoplasma | 6 | 0.97(0.79-1.19) | 0.738 | 48.3 % | 0.085 | |

| Cytoplasma or nuclearus | 4 | 0.92(0.83-1.04) | 0.226 | 0 % | 0.565 | |

| Cytoplasma and nuclearus | 1 | 1.09(0.71-1.67) | 0.691 | / | / |

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

The sensitivity analysis demonstrated that a single study had no significant effect on the pooled RRs. Egger’s test based on the 19 literatures which provided the comparison between NSCLC patients and normal controls revealed the presence of publication bias (P = 0.001). After the application of fill and trim method, statistical significance still existed on the survivin expression between NSCLC patients and normal controls (P < 0.001), suggesting publication bias has no significant effect on the final results. For those studies investigated pathological types (n = 22), histological differentiation (n = 21), TNM stage (n = 26), lymphatic metastasis (n = 25) and tumor size (n = 11), no publication biases were found by Egger’s test.

Meta-regression analysis

Univariate meta-regression analysis revealed that country and ethnicity may be the potential sources for most of heterogeneity (P > 0.05). Multivariate meta-regression analysis further confirmed this finding (Table 4).

Table 4.

Meta-regression analyseis of potential source of heterogeneity

| Heterogeneity factors | Coefficient | SE | t | P | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| Country | 82.25 | 25.89 | 3.18 | 0.037 | 27.37 | 137.13 |

| Ethnicity | 78.35 | 27.13 | 3.08 | 0.025 | 26.15 | 120.65 |

| Language | 8.82 | 18.07 | 0.49 | 0.598 | −29.49 | 47.12 |

| Sample Size | −0.18 | 0.37 | −0.49 | 0.234 | −26.96 | 102.39 |

(Notes: SE = Standard Error; LL = Lower Limit; UL = Upper Limit)

Discussion

The tumorigenesis of NSCLC is a complex process with the feature of imbalance in cell apoptosis and proliferation. Aberrant proliferation of tumor cells may emerge as cell apoptosis is inhibited, which eventually provided supports for tumorigenesis, development, invasion and metastasis [37]. Survivin is one of the most important inhibitor of IAP family, which is normally expressed in embryonic and fetal tissues but is almost absent in terminally differentiated cells [6, 38]. Its overexpression has been reported in many malignancies including NSCLC. [39] Several studies have reported survivin overexpression was involved in the development of NSCLC [7, 8].

The result of meta-analysis showed a significant difference in survivin expression between NSCLC patients and normal controls. To investigate the correlation between survivin expression and clinicopathologic characteristics, we performed several meta-analysis in NSCLC patients classified by clinicopathologic parameters. Our results suggested survivin expression was associated to histological differentiation, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage and lymph node metastasis (LNM). Roles of survivin in the progression of NSCLC have been investigated previously. Babaei et al. reported survivin is associated with high grade malignancies. [40] Significant overexpression of survivin was observed in NSCLC patients at late stage. [41] A strong heterogeneity was detected among individual studies. Meta-regression indicated ethnicity was the primary source of heterogeneity. In the subgroup analysis classified by ethnicity, the significant associations were still present in Asians but not in Caucasians. One possible reason was that only few studies were conducted in Caucasians and no firm conclusions can be draw from a small sample set. Further research with large sample size is needed to define the impact of survivin expression in Caucasians.

Survivin has been shown to localize in mitochondria, cytoplasm and nucleus. And the functional dynamics of survivin are dependent on its subcellular localization. [42] Localization of survivin to the nucleus and cytoplasm confers its role in mitosis regulation and apoptosis inhibition. [43] In nucleus, survivin is involved in the chromosomal packaging complex and controls mitosis in many aspects including regulations of the mitotic spindle checkpoint and mitotic progression. [44] As an inhibitor in IAP family, survivin can directly inhibit caspase-3 and caspase-7 activity to prevent apoptosis [5]. In the studies included in our meta-analysis, most studies reported cytosol survivin expression only. Several studies defined positive expression as survivin expression in cytoplasm or nucleus. Only in 2 studies survivin expression in both cytoplasm and nucleus was considered as positive expression. We performed subgroup analysis according to the subcellular localization of survivin and only found the 2 studies with survivin expression in both cytoplasm and nucleus gave different results with other subgroups. Further research is necessary to determine with precision whether there is a correlation between subcellular localization of survivin expression and progression of NSCLC.

There were several limitations in our present meta-analysis. First, for the insufficiency of data, we did not analyze whether survivin expression is correlated the prognosis of NSCLC. Secondly, although our meta-analysis included 28 studies, only 4 studies were performed in Caucasians. Thus, no firm conclusions can be draw in Caucasians and the difference between Asians and Caucasians is uncertain.

Conclusions

In conclusion, although our meta-analysis has some shortcomings, it still provides evidence that survivin expression was associated with the clinicopathologic characteristics of NSCLC in Asians, suggesting that survivin protein can serves as an important biomarker for the progression of NSCLC. However, further investigations with more integral data are needed to determine the correlation of survivin expression and the progression of NSCLC in Caucasians.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all of the colleague in the team of Department of Thoracic Surgery, which provided advice for preparing the manuscript.

Fundings

No funding.

Abbreviations

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- TNM

Tumor-node-metastasis

- LNM

Lymph node metastasis

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa scale

- RR

Risk ratios

- CI

Confidence interval

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma

- AC

Adenocarcinoma

- IAP

Inhibitor of the apoptosis protein

Footnotes

Liang Duan and Xuefei Hu are first co-author.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Authors LD and QJY conceived and designed the experiments. XFH and YXJ performed the experiments. RJL analyzed the data. LD, RJL and QJY contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools LD and QJY contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Liang Duan, Email: liangduanplos@163.com.

Qingjun You, Email: Qingjunyouplos@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Yun F, Jia Y, Li X, Yuan L, Sun Q, Yu H, Shi L, Yuan H. Clinicopathological significance of PTEN and PI3K/AKT signal transduction pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6(10):2112–2120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pao W, Girard N. New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):175–180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du Y, Su T, Zhao L, Tan X, Chang W, Zhang H, Cao G. Associations of polymorphisms in DNA repair genes and MDR1 gene with chemotherapy response and survival of non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen WL, Kuo KT, Chou TY, Chen CL, Wang CH, Wei YH, Wang LS. The role of cytochrome c oxidase subunit Va in non-small cell lung carcinoma cells: association with migration, invasion and prediction of distant metastasis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:273. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akyurek N, Memis L, Ekinci O, Kokturk N, Ozturk C. Survivin expression in pre-invasive lesions and non-small cell lung carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2006;449(2):164–170. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jha K, Shukla M, Pandey M. Survivin expression and targeting in breast cancer. Surg Oncol. 2012;21(2):125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawasaki H, Toyoda M, Shinohara H, Okuda J, Watanabe I, Yamamoto T, Tanaka K, Tenjo T, Tanigawa N. Expression of survivin correlates with apoptosis, proliferation, and angiogenesis during human colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer. 2001;91(11):2026–2032. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010601)91:11<2026::AID-CNCR1228>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo Muzio L, Pannone G, Leonardi R, Staibano S, Mignogna MD, De Rosa G, Kudo Y, Takata T, Altieri DC. Survivin, a potential early predictor of tumor progression in the oral mucosa. J Dent Res. 2003;82(11):923–928. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halasova E, Adamkov M, Matakova T, Vybohova D, Antosova M, Janickova M, Singliar A, Dobrota D, Jakus.Expression of Ki-67, Bcl-2, Survivin and p53 Proteins in Patients with Pulmonary Carcinoma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;756:15-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Yoo J, Jung JH, Lee MA, Seo KJ, Shim BY, Kim SH, Cho DG, Ahn MI, Kim CH, Cho KD, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of non-small cell lung cancer: correlation with clinical parameters and prognosis. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22(2):318–325. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.2.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirano H, Maeda H, Yamaguchi T, Yokota S, Mori M, Sakoda S. Survivin expression in lung cancer: Association with smoking, histological types and pathological stages. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(3):1456–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Hu S, Qu Y, Xu X, Xu Q, Geng J, Xu J. Nuclear survivin and its relationship to DNA damage repair genes in non-small cell lung cancer investigated using tissue array. PloS one. 2013;8(9):e74161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Shinohara ET, Gonzalez A, Massion PP, Chen H, Li M, Freyer AS, Olson SJ, Andersen JJ, Shyr Y, Carbone DP, et al. Nuclear survivin predicts recurrence and poor survival in patients with resected nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103(8):1685–1692. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun PL, Jin Y, Kim H, Seo AN, Jheon S, Lee CT, Chung JH. Survivin expression is an independent poor prognostic marker in lung adenocarcinoma but not in squamous cell carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2013;463(3):427–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Chen YQ, Zhao CL, Li W. Effect of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha on transcription of survivin in non-small cell lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:29. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan CF, Xu HT, Lin XY, Yu JH, Wang EH. A multiple marker analysis of apoptosis-associated protein expression in non-small cell lung cancer in a Chinese population. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2011;49:231–9. doi: 10.5603/FHC.2011.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao Q, Yang S, Kang MQ. Influence of survivin and Bcl-2 expression on the biological behavior of non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5(6):1409–1414. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guosheng L, Xuhan L, Daorong Z, Dong L, Zhiyong L. The expression and significance of cyclin B1 and survivin in human non-small cell lung cancer. Chin Ger J Clin Oncol. 2011;10(4):192–197. doi: 10.1007/s10330-011-0771-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu FQ, Zhong H, Wang L, Li GQ, Mei J. Expression of Survivin and its Correlation with VEGF in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Progress in Modern Biomedicine. 2011;11(24):4864–4867. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huo XD, Sun QN, Li GH. Expression and Clinical Significance of Survivin, Caspase-3, Gst and Pgp in Nsclc. Acta Academiae Medicinae Neimongol. 2006;28(4):279–283. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li CH, Hu B, Wang XQ, Li CS, He YF. Expression and clinical significance of caspase-3、survivin and k-ras in non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Lung Canc. 2008;11(1):90–96. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li XC, Min JX, Jiang L, Yao K, Zhang GQ. Expression and relationship of survivin gene and p16 protein in non-small-cell lung cancer. Acta Academiae Medicinae Militaris Tertial. 2006;28(22):2289–2292. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miao LJ, Wang J, Wu QG, Sun ZT, Wu YM, Wu YJ. Expression of Activated AKT, Survivin and Bcl-2 in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Tianjin Medical Journal. 2007;35(4):241–243. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porebska I, Sobańska E, Kosacka M, Jankowska R. Apoptotic regulators:P53 and survivin expression in non small cell lung cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2010;7:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu HL, Ding W, Zhou JY. Zhejiang Journal of Preventive Medicine. Expression of Survivin in Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma of Human and Its Association with COX-2 and Apoptosis. 2005;17(7):1–2,10.

- 26.Ren YJ, Zhang QY. Expression of survivin and its clinical significance in non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Peking University(HealthSciences). 2005;37(5):504–7. [PubMed]

- 27.Shi M, Yu SY. The relationship between expression of survivin, P53, Bcl- 2 with the clinicopathologic factors in non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Modern Oncology. 2007;15(2):193–196. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vischioni B, Oudejans JJ, Vos W, Rodriguez JA, Giaccone G. Frequent overexpression of aurora B kinase, a novel drug target, in non-small cell lung carcinoma patients. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(11):2905–2913. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang M, Chen GY, Lin T. Expression and Correlation of survivin and VEGF in NSCLC. Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment. 2006;33(1):5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M, Liu BG, Yang ZY, Hong X, Chen GY. Significance of survivin expression: Prognostic value and survival in stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2012;3(6):983–988. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu P, Xu XL, Huang Q, Zhang ZH, Zhang YB. CIP2A with survivin protein expressions in human non-small-cell lung cancer correlates with prognosis. Med Oncol. 2012;29(3):1643–1647. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xue ZX, Liu JX, He J, Deng XH. Study of the expression and the relationship of Cox-2 and Survivin on non-small cell lung cancer. Chin Clin Oncol. 2006;11(10):735–738. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang DX, Li NE, Ma Y, Han YC, Shi Y. Expression of Elf-1 and survivin in non-small cell lung cancer and their relationship to intratumoral microvessel density. Chin J Cancer. 2010;29(4):434–441. doi: 10.5732/cjc.009.10547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng ZH. FHIT expression and the relationship with expressions of Survivin and Ezrin proteins in non-small cell lung cancer. Chinese Medical Herald. 2010;07(20):12–14,20. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang XY, Jiang JG, Zhai ZY, Zheng YY, Liu RF, Zhang JW, Yang C, Sun M. Expression and significance of apoptosis related gene Survivin in non small cell lung cancer. Chin J Gerontol. 2012;32(11):2227–2228. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu CZ, Li F, Li Y, Wang XY. Survivin and COX-2 expression in non-small cell lung cancer:Association with tumorigenesis and development of lung cancer. Journal of Tianjin Medical University. 2010;16(3):433–436. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407(6805):770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ambrosini G, Adida C, Altieri DC. A novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and lymphoma. Nat Med. 1997;3(8):917–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang XP, Li J, Yu LC, Chen YC, Shi SB, Zhu LR, Chen P. Clinical significance of survivin and VEGF mRNA detection in the cell fraction of the peripheral blood in non-small cell lung cancer patients before and after surgery. Lung Cancer. 2013;81(2):273–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Soleimanpour E, Babaei E. Survivin as a Potential Target for Cancer Therapy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(15):6187–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Javid J, Mir R, Julka PK, Ray PC, Saxena A. Role of survivin re-expression in the development and progression of non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(7):5543–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Khan S, Ferguson Bennit H, Asuncion Valenzuela MM, Turay D, Diaz Osterman CJ, Moyron RB, Esebanmen GE, Ashok A, Wall NR. Localization and upregulation of survivin in cancer health disparities: a clinical perspective. Biologics. 2015;9:57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Fortugno P, Wall NR, Giodini A, O'Connor DS, Plescia J, Padgett KM, Tognin S, Marchisio PC, Altieri DC. Survivin exists in immunochemically distinct subcellular pools and is involved in spindle microtubule function. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 3):575–585. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Church DN, Talbot DC. Survivin in solid tumors: rationale for development of inhibitors. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14(2):120–28. [DOI] [PubMed]