Abstract

The elucidation of the molecular alterations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and the development of molecularly targeted agents have permanently shifted NSCLC therapy to a personalized approach. In the metastatic setting, the addition of the anti–vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody, bevacizumab, to chemotherapy improves overall survival. The oral epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors, gefitinib and erlotinib, prolong progression-free survival in patients selected for the presence of an EGFR activating mutation. The monoclonal antibody to EGFR, cetuximab, improves survival in patients with metastatic NSCLC, and the inhibitor of the echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (EML4-ALK) fusion protein, crizotinib, has resulted in an unprecedented overall survival advantage in patients harboring the EML4-ALK translocation. In the adjuvant setting, gefitinib has not been shown to improve patient survival outcomes; however, there are several ongoing clinical trials in the adjuvant setting evaluating the role of erlotinib, bevacizumab, and the MAGE-A3 and MUC1 vaccines. The realm of personalized lung cancer therapy also includes the study of chemotherapy selected on the basis of the pharmacogenetic profile of a patient’s tumor. Several ongoing clinical trials in both the metastatic and adjuvant settings are studying the excision repair cross-complementing group 1 (ERCC1) protein, the ribonucleotide reductase subunit 1 (RRM1) protein, thymidylate synthase, and BRCA1 as predictors of chemotherapy response. This review will outline the current state of the art of personalized NSCLC therapy.

Keywords: non-small cell lung cancer, targeted therapy

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States.1 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 85% of all lung cancers, and small cell lung cancer accounts for about 15%.2 Historically, NSCLC was treated as a single disease entity, and palliative chemotherapy in the metastatic setting resulted in modest survival prolongation and preservation of quality of life.3–7 A series of large randomized controlled phase III clinical trials established platinum-based doublets as the standard of care in the treatment of metastatic NSCLC, with response rates of 20%–30% and a median survival of 8–11 months.8–12

NSCLC therapy has evolved with the development of targeted agents against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and the inhibitor of the echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (EML4-ALK) fusion protein. Lynch et al13 and Paez et al14 first described a subset of patients with NSCLC harboring activating mutations in the EGFR gene who responded to treatment with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). This discovery permanently shifted the landscape of NSCLC therapy to a personalized approach based on the molecular alterations of a patient’s tumor (Table 1). The realm of personalized lung cancer therapy also includes several clinical trials studying the selection of chemotherapy on the basis of the pharmacogenetic profile of a patient’s tumor. This review will highlight the molecular alterations in lung cancer that are therapeutic targets in the metastatic and adjuvant setting and also discuss the ongoing trials in the realm of personalized pharmacogenomic-driven NSCLC therapy.

Table 1.

Molecular Alterations in Advanced NSCLC

| Molecular Aberration | Frequency |

|---|---|

| EGFR mutation | ~10% Northern Americans and Western Europeans25 |

| ~30%–50% East Asians25 | |

| ~>50% Nonsmokers with adenocarcinoma25 | |

| EML4-ALK fusion | 5%–7%49 |

| KRAS mutation | 17%–19%40,76,77 |

| PI3K amplification | 12%78 |

| PI3K mutation | 3%–5%79 |

| MET amplification | 3%–22%43,44,80 |

| MET mutation | 3%81 |

| BRAF mutation | 3%82 |

| Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor gene amplification | 3%83 |

TARGETED AGENTS IN THE TREATMENT OF METASTATIC NSCLC

Inhibitors of VEGF

Increased expression of VEGF, an endothelial specific mitogen, has been found in most human tumors, including NSCLC, and is associated with increased tumor recurrence, metastasis, and death.15–19 Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against VEGF and has been studied in 2 large randomized phase III clinical trials in patients with nonsquamous histology in the first-line setting.20,21 The phase II clinical trial of bevacizumab in the first-line setting resulted in excess pulmonary hemorrhage in patients with squamous histology; thus the use of bevacizumab is limited to the nonsquamous setting.22

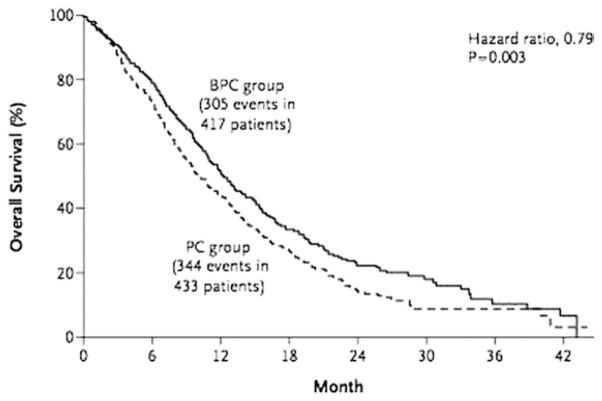

In the landmark intergroup trial E4599, the addition of bevacizumab to carboplatin/paclitaxel significantly improved median overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with chemotherapy alone (12.3 versus 10.3 months; hazard ratio (HR), 0.79; P = 0.003; Fig. 1, Table 2).20 The European counterpart, AVAiL, evaluated the addition of 1 of 2 doses of bevacizumab (7.5 mg/kg or 15 mg/kg) to cisplatin/gemcitabine versus chemotherapy alone. This trial met its primary end point, with a significant prolongation in progression-free survival (PFS) from 6.1 to 6.7 months in the low-dose bevacizumab group (HR, 0.75; P = 0.003; Table 2) and from 6.1to 6.5 months in the high-dose bevacizumab group (HR, 0.82; P = 0.03; Table 2).21 The update of AVAiL failed to demonstrate an OS advantage (13.1, 13.4, and 13.6 months for placebo, high-dose bevacizumab, and low-dose bevacizumab groups, respectively; HR, 1.03; P = 0.761; Table 2), although more than 60% of patients with progression of their disease had gone on to receive second-line therapy.23

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimate for overall survival in patients treated with bevacizumab/paclitaxel/carboplatin (BPC) and paclitaxel/carboplatin (PC) in the E4599 intergroup trial.20 (Reprinted with permission from Sandler et al,20 ©2006 Massachusetts Medical Society.)

Table 2.

| Study | Setting | Study Arms | No. of Patients | RR (%) | PFS (mo) | OS (mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF monoclonal antibody | ||||||

| E459920 | 1st line | Carboplatin/paclitaxel + bevacizumab | 434 | 35.0 | 6.2 | 12.3 |

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel | 444 | 15.0 | 4.5 | 10.3 | ||

| AVAiL21,23 | 1st line | Cisplatin/gemcitabine + LD bevacizumab | 345 | 34.1 | 6.1 | 13.6 |

| Cisplatin/gemcitabine + HD bevacizumab | 351 | 30.4 | 6.7 | 13.4 | ||

| Cisplatin/gemcitabine | 347 | 20.1 | 6.5 | 13.1 | ||

| Pointbreak | 1st line | Carboplatin/paclitaxel + bevacizumab | Ongoing | |||

| Carboplatin/pemetrexed + bevacizumab | ||||||

| EGFR TKIs | ||||||

| Clinically selected patients | ||||||

| IPASS26,27 | 1st line | Gefitinib | 609 | 43.0 | 5.7 | 18.8 |

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel | 608 | 32.2 | 5.8 | 17.4 | ||

| FIRST-SIGNAL28 | 1st line | Gefitinib | 159 | 53.5 | 5.9 | 20.3 |

| Cisplatin/gemcitabine | 150 | 42.0 | 5.8 | 23.1 | ||

| Molecularly selected patients | ||||||

| EURTAC29 | 1st line | Erlotinib | 77 | 54.5 | 9.4 | 22.9 |

| Chemotherapy | 76 | 10.5 | 5.2 | 18.8 | ||

| OPTIMAL30 | 1st line | Erlotinib | 82 | 86.0 | 13.1 | NM |

| Carboplatin/gemcitabine | 72 | 36.0 | 4.6 | |||

| Maemondo et al31 | 1st line | Gefitinib | 115 | 73.7 | 10.8 | 30.5 |

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel | 115 | 30.7 | 5.4 | 23.6 | ||

| WJTOG 340532 | 1st line | Gefitinib | 86 | 62.1 | 9.2 | NM |

| Cisplatin/docetaxel | 86 | 32.2 | 6.3 | |||

| Subsequent therapy | ||||||

| BR2133 | 2nd/3rd line | Erlotinib | 488 | 8.9 | 2.2 | 6.7 |

| Placebo | 243 | <1.0 | 1.8 | 4.7 | ||

| ISEL34 | 2nd/3rd line | Gefitinib | 1129 | 8.0 | 3.0* | 5.6 |

| Placebo | 563 | 1.3 | 2.6* | 5.1 | ||

| LUX-Lung145 | 2nd/3rd line | Afatinib | 390 | 11.0 | 3.3 | 10.8 |

| Placebo | 195 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 12.0 | ||

| Combined chemotherapy and EGFR TKI | ||||||

| TRIBUTE35 | 1st line | Carboplatin/paclitaxel + erlotinib | 526 | 21.5 | 5.1† | 10.6 |

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel | 533 | 19.3 | 4.9† | 10.5 | ||

| INTACT-136 | 1st line | Cisplatin/gemcitabine + erlotinib 500 mg/d | 365 | 49.7 | 5.5† | 9.9 |

| Cisplatin/gemcitabine + erlotinib 250 mg/d | 365 | 50.3 | 5.8† | 9.9 | ||

| Cisplatin/gemcitabine | 363 | 44.3 | 6.0† | 10.9 | ||

| INTACT-237 | 1st line | Carboplatin/paclitaxel + erlotinib 500 mg/d | 347 | 30.0 | 4.6† | 8.7 |

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel + erlotinib 250 mg/d | 345 | 30.4 | 5.3† | 9.8 | ||

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel | 345 | 28.7 | 5.0† | 9.9 | ||

| TALENT38 | 1st line | Cisplatin/gemcitabine + erlotinib | 580 | 31.5 | 25.4‡ | 43.0 |

| Cisplatin/gemcitabine | 579 | 29.9 | 23.9‡ | 44.1 | ||

| EGFR monoclonal antibodies | ||||||

| FLEX39 | 1st line | Cisplatin/vinorelbine + cetuximab | 557 | 36.0 | 4.8 | 11.3 |

| Cisplatin/vinorelbine | 568 | 29.0 | 4.8 | 10.1 | ||

| BMS09984 | 1st line | Carboplatin/taxane + cetuximab | 338 | 25.7 | 4.4 | 9.7 |

| Carboplatin/taxane | 338 | 17.2 | 4.2 | 8.4 | ||

| Combined targeted therapy | ||||||

| BeTa41 | 2nd line | Erlotinib + bevacizumab | 319 | 13.0 | 3.4 | 9.3 |

| Erlotinib + placebo | 317 | 6.0 | 1.7 | 9.2 | ||

| ALK TKI | ||||||

| Kwak et al50 | All lines | Crizotinib | 82 | 57.0 | NM | |

| PROFILE 100585 | All lines | Crizotinib | 136 | 54.0 | NM | |

RR, response rate; NM, not mature.

Time to treatment failure.

Time to progression.

Duration of response.

In an embedded substudy of E4599, the onset of hypertension with bevacizumab portended better OS and PFS relative to patients who did not have onset of hypertension.24 However, selection of patients who are most likely to benefit from chemotherapy plus bevacizumab is limited by the lack of a validated biomarker of response to VEGF therapy. Outstanding questions also include which platinum doublet is best paired with bevacizumab in the nonsquamous setting, carboplatin/paclitaxel versus carboplatin/pemetrexed. This is the subject of the ongoing clinical trial Pointbreak, which has enrolled 900 patients with metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC, with the primary end point of OS.

Inhibitors of EGFR

EGFR is a receptor tyrosine kinase that is a crucial component of the activation of cell signaling pathways, which include the Ras-Raf-Mek pathway and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway.2 These pathways can in turn be modulated by other receptor tyrosine kinases, such as the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and cMET, and, in concert, affect cell proliferation, local invasion, metastasis, resistance to apoptosis, and angiogenesis.2 Sensitizing EGFR mutations most commonly occur as in-frame deletions of exon 19 (45%) and the L858R substitution in exon 21 (40%–45%), whereas nucleotide substitutions in exon 18 and in-frame insertions of exon 20 account for another 5%.25 EGFR gene mutations are present in up to 10% of Northern Americans and Western Europeans, 30%–50% of East Asians, and more than 50% of patients who are nonsmokers with adenocarcinoma histology (Table 1).25 Thus, EGFR has been exploited as a therapeutic target of EGFR TKIs and monoclonal antibodies targeted against EGFR.

The IPASS clinical trial evaluated the efficacy of gefitinib in the first-line setting in patients who were clinically selected on the basis of adenocarcinoma histology, Asian ethnicity, and never- or light-smoking status. This trial met its primary end point of PFS with respect to noninferiority and demonstrated superiority of gefitinib to chemotherapy (5.7 versus 5.8 months; HR, 0.74; P < 0.001; Table 2), with a 12-month PFS rate of 24.9% in the gefitinib arm and 6.7% in the carboplatin/paclitaxel arm.26 This trial did not demonstrate an OS advantage with gefitinib treatment (18.8 versus 17.4 months; HR, 0.90; P = 0.109; Table 2), likely owing to the high crossover rate to subsequent therapies.27 In the biomarker analysis of IPASS, patients with EGFR mutations had a significantly longer PFS with gefitinib compared with chemotherapy (HR, 0.48; P < 0.001), whereas patients without EGFR mutations had a worse PFS with gefitinib compared with chemotherapy (HR, 2.85; P < 0.001). Similarly, the FIRST-SIGNAL trial selected patients on the basis of clinical criteria and demonstrated superior PFS for gefitinib compared with chemotherapy (5.9 versus 5.8 months; HR, 0.74; P = 0.0063; Table 2), with a significantly longer PFS in patients with an EGFR mutation compared with those without a mutation (7.9 versus 2.1 months; HR, 0.385; P = 0.009). This trial also did not demonstrate a statistically significant OS advantage with gefitinib (Table 2).28

A series of clinical trials have been conducted in patients selected on the basis of the presence of an EGFR mutation and have consistently demonstrated superior PFS with EGFR TKI therapy compared with chemotherapy in the first-line setting. Erlotinib was compared with chemotherapy in the EURTAC clinical trial and resulted in a PFS of 9.4 months compared with 5.2 months in the chemotherapy arm (HR, 0.42; P < 0.0001; Table 2),29 and in the clinical trial OPTIMAL, erlotinib resulted in a PFS advantage of 13.1 months compared with 4.6 months in the chemotherapy arm (HR, 0.16; P < 0.0001; Table 2).30 Maemondo et al31 demonstrated that gefitinib resulted in a superior PFS when compared with chemotherapy (10.8 versus 5.4 months; HR, 0.30; P < 0.001; Table 2), and WJTOG3405 demonstrated a PFS of 9.2 months with gefitinib compared with 6.3 months with chemotherapy (HR, 0.49; P < 0.0001; Table 2).32 EURTAC and Maemondo et al failed to demonstrate a statistically significant OS advantage. As with prior trials, there was a high crossover rate after progression of disease. In the study by Maemondo et al, more than 65% patients who had discontinued gefitinib went on to receive chemotherapy, and 95% of patients who had completed first-line carboplatin/paclitaxel went on to receive gefitinib in the second-line setting with a response rate of 60%. These trials established EGFR TKI therapy as the treatment of choice in the first-line setting in patients with sensitizing EGFR mutations.

Beyond the first-line setting, the BR21 clinical trial demonstrated an advantage in PFS (2.2 versus 1.8 months; HR, 0.61; P < 0.001; Table 2) and in OS (6.7 versus 4.7 months; HR, 0.70; P < 0.001; Table 2) with erlotinib relative to best supportive care.33 The ISEL trial also demonstrated a PFS advantage with gefitinib over placebo (3.0 versus 2.6 months; HR, 0.82; P = 0.0006; Table 2) but did not demonstrate an advantage with regard to the primary end point, OS (5.6 versus 5.1 months; HR, 0.89; P = 0.087; Table 2).34 The patients in both these studies were not selected on the basis of clinical or molecular criteria, and thus, EGFR TKI therapy is reasonable in the setting of progressive disease, regardless of histology or mutational status.

The TRIBUTE clinical trial studied the efficacy of combining an EGFR TKI with chemotherapy in the first-line setting in NSCLC regardless of histology. This trial randomized patients to carboplatin/paclitaxel with or without erlotinib and found no advantage with regard to time to progression (TTP) (5.1 versus 4.9 months; HR, 0.937; P = 0.36; Table 2).35 The INTACT-1 and INTACT-2 clinical trials randomized patients to 1 of 2 doses of erlotinib plus platinum-based chemotherapy and demonstrated no statistically significant advantage in TTP (Table 2).36,37 The TALENT clinical trial of cisplatin/gemcitabine with or without erlotinib demonstrated a modest prolongation of duration of response with the addition of erlotinib to chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone (6.4 versus 6.0 months; HR, 0.77; P = 0.45; Table 2)38; however, the body of evidence as a whole does not support the addition of erlotinib to chemotherapy in the first-line setting.

Cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody to EGFR, was evaluated in the FLEX clinical trial, which randomized patients of all NSCLC histologies with immunohistochemical evidence of EGFR expression to cisplatin/vinorelbine with or without cetuximab. This study failed to demonstrate an advantage in PFS for the addition of cetuximab (4.8 months for both treatment arms; HR, 0.943; P = 0.39; Table 2) but did demonstrate a modest OS advantage of 11.1 months for the chemotherapy plus cetuximab arm compared with 10.1 months for the chemotherapy alone arm (HR, 0.871; P = 0.044; Table 2).39 The BMS099 clinical trial compared carboplatin/taxane with or without cetuximab in patients with all histologies without regard for EGFR immunohistochemistry; there was no statistically significant benefit in PFS but a trend toward improved OS (9.7 versus 8.4 months; HR, 0.890; P = 0.1685; Table 2).40

Combining targeted therapies in the second-line setting was studied in the BeTa trial, which compared erlotinib with or without bevacizumab. This trial failed to meet its primary end point of OS (Table 2).41 Although PFS seemed significant (3.4 months on the combination arm versus 1.7 months in the erlotinib alone arm; HR, 0.62), the study design required that the primary end point be met before testing of the secondary end point; therefore, this difference could not be deemed statistically significant.

One of the most relevant EGFR mutations is the T790M mutation in exon 20, which is found in 50% of patients who have acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors.42–44 In the LUX-Lung1 clinical trial, the novel irreversible TKI of EGFR and HER2, afatinib, was evaluated in patients who had progression of their disease after 12 or more weeks of therapy with erlotinib or gefitinib. Although this study failed to demonstrate an OS advantage with afatinib compared with best supportive care (10.8 versus 12.0 months; HR, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 0.86–1.35), there was a 3-fold increase in PFS from 1.1 to 3.3 months with afatinib (HR, 0.38; P < 0.0001).45

Inhibitors of ALK

The EML4-ALK fusion oncogene results from an inversion in chromosome 2p, which leads to a constitutively active chimeric tyrosine kinase with potent oncogenic activity.46–48 The EML4-ALK fusion oncogene occurs in 5%–7% of NSCLC cases and is more likely to occur in patients who are younger, male, never or light smokers, and in patients with adenocarcinoma histology (Table 1).49

In the seminal phase I clinical trial of the ALK inhibitor crizotinib in patients harboring EML4-ALK, 82 patients were treated with crizotinib, with an overall response rate of 57% and a stable disease rate of 33%.50 Shaw et al51 reported on the impact of crizotinib on OS in patients with advanced EML4-ALK–positive NSCLC compared with historical controls. The use of crizotinib in EML4-ALK–positive patients resulted in an unprecedented survival benefit with 1-year OS of 77%, 2-year OS of 64%, and median OS that has not been reached. Patients with ALK rearrangements who were not treated with crizotinib had 1- and 2-year OS rates of 73% and 33%, respectively. In the second- and third-line setting, the survival of 32 patients with ALK rearrangements treated with crizotinib was significantly longer than that of 24 patients with ALK rearrangements not treated with crizotinib (OS not reached for the ALK-positive crizotinib-treated patients versus 11 months for the ALK-positive patients not treated with crizotinib; P = 0.004). On the basis of these compelling results, crizotinib was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of NSCLC harboring ELM4-ALK rearrangements. The phase II clinical trial, PROFILE 1005, and the 2 phase III clinical trials in the first- and second-line settings are still ongoing (Table 2).

TARGETED AGENTS IN THE ADJUVANT SETTING

Inhibitors of VEGF

A series of large randomized phase III clinical trials have demonstrated an OS benefit with adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy in the treatment of early-stage resected NSCLC.20,21 The intergroup trial E4599 and the AVAiL clinical trial demonstrated a benefit from the addition of bevacizumab to platinum-based chemotherapy in the metastatic setting and provide the rationale for the addition of bevacizumab to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting. This is the subject of the ongoing intergroup trial E1505, which will enroll 1500 patients with resected stage IB to IIIA disease and randomize to cisplatin-based chemotherapy with or without the addition of bevacizumab. The primary end point will be OS, with secondary end points of disease-free survival, toxicity, and molecular correlates for the prediction of clinical outcome.

Inhibitors of EGFR

On the basis of the activity of EGFR TKIs in clinically and molecularly selected patients with advanced NSCLC, the phase III clinical trial BR.19 evaluated the role of gefitinib in patients with stage IB to IIIA NSCLC who had undergone complete resection.52 Gefitinib compared with placebo failed to demonstrate a benefit in the adjuvant setting with regard to OS (5.1 years versus OS not reached; HR, 1.24; P = 0.14; Table 3) and disease-free survival (4.2 years versus disease-free survival not reached; HR, 1.22; P = 0.15; Table 3). In an exploratory analysis, neither EGFR nor KRAS mutational status was prognostic or predictive of benefit from gefitinib. It is important to note that this trial was stopped early after the ISEL clinical trial failed to demonstrate an OS advantage with gefitinib in the metastatic setting. Thus, BR.19 failed to meet its accrual goal, and the duration of adjuvant gefitinib was short. These results will be corroborated with the ongoing phase III clinical trial, RADIANT, which is comparing erlotinib with placebo in the adjuvant setting. The target accrual is 945 patients, and the primary end point is disease-free survival, with secondary end points of OS and toxicity.

Table 3.

Phase III Trials Evaluating Targeted Agents in the Adjuvant Setting

| Study | Study Arms | No. of Patients | DFS (mo) | OS (mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF antagonists | ||||

| E1505 | CT + bevacizumab | Ongoing | ||

| CT | ||||

| EGFR inhibitors | ||||

| BR.1952 | Gefitinib | 251 | 4.2 | 5.1 |

| Placebo | 252 | NR | NR | |

| RADIANT | Erlotinib | Ongoing | ||

| Placebo | ||||

| Vaccine trials | ||||

| MAGRIT | MAGE-A3 vaccine | Ongoing | ||

| Placebo | ||||

| START | BLP25 liposomal vaccine | Ongoing | ||

| Placebo | ||||

DFS, disease-free survival; CT, cisplatin-based doublet chemotherapy; NR, not reached.

In patients with stage III NSCLC with stable or responding disease after treatment with definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

VACCINE TRIALS

Cancer immunotherapy exploits a patient’s own immune system to elicit a T-cell response against cancer cells.53–57 MAGE-A3 is a tumor-specific antigen that is expressed in 35%–50% of NSCLC cases and is not expressed in normal tissue, except the testes and placenta, which lack the protein essential for antigen presentation to T cells.58 As such, MAGE-A3 is an ideal immunotherapeutic target and the subject of a proof-of-concept phase II clinical trial of the MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic (recombinant MAGE-A3 and a potent immune adjuvant) conducted in patients with completely resected stage IB and II NSCLC.59 This trial enrolled 182 patients and demonstrated a trend toward improved disease-free interval (HR, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.44–1.20), disease-free survival (HR, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.45–1.160), and OS (HR, 0.066; 95% confidence interval, 0.36–1.20). On the basis of these results, there is an ongoing phase III clinical trial, MAGRIT, evaluating the efficacy of the MAGE-A3 vaccine in the adjuvant setting in MAGE-A3–positive patients with resected stage IB to IIIA NSCLC. This trial will enroll 2270 patients, with the primary end point of disease-free survival and the secondary end point of validating a gene signature as a predictor of benefit from the MAGE-A3 vaccine.

MUC1 is a human mucin gene that is overexpressed in NSCLC compared with corresponding normal tissue and is the target of the immunotherapeutic liposomal vaccine, BLP25.60 The BLP25 liposomal vaccine was evaluated in a randomized phase IIb clinical trial of 171 patients with stage IIIB and IV NSCLC who had stable or responding disease after first-line chemotherapy.61 This trial demonstrated a 4.4-month trend toward prolonged median OS (HR, 0.739; P = 0.112), with the greatest benefit in patients with stage IIIB disease (median OS not been reached in the BLP25 liposomal vaccine arm versus 13.3 months for the best supportive care arm; HR, 0.524; P = 0.69). On the basis of these results, the START study was designed as a phase III clinical trial of the BLP25 liposomal vaccine in patients with stage III disease who have been treated definitely with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. This trial will accrue 1476 patients, with the primary end point of OS.

PREDICTORS OF RESPONSE TO PLATINUM-BASED CHEMOTHERAPY

The realm of personalized lung cancer therapy also includes the study of chemotherapy selection on the basis of the pharmacogenetic profile of a patient’s tumor. The excision repair cross-complementing group 1 (ERCC1) protein is a key component of nucleotide excision repair in response to platinum-induced DNA adducts.62–64 Ribonucleotide reductase subunit M1 (RRM1) is crucial for nucleotide metabolism and a molecular determinant of gemcitabine efficacy.65–68 MADeIt was a prospective phase II clinical trial in which patients with advanced NSCLC were required to have tumor biopsies for ERCC1 and RRM1 expression.69 Patients were then assigned to 1 of 4 chemotherapeutic regimens on the basis of the level of expression of these 2 proteins. Patients with low expression of both were assigned to carboplatin/gemcitabine, patients with low RRM1 and high ERCC1 expression were assigned to gemcitabine/docetaxel, patients with high RRM1 and low ERCC1 expression were assigned to carboplatin/docetaxel, and patients with high RRM1 and ERCC1 were assigned to docetaxel/vinorelbine. This strategy resulted in a promising response rate of 44%, with median OS of 13.3 months and median PFS of 6.6 months. This study demonstrated the feasibility of therapeutic decision-making on the basis of ERCC1 and RRM1 gene expression, which is the subject of an ongoing phase III clinical trial, also called MADeIt (Table 4).

Table 4.

Trials of Predictive Biomarkers of Chemotherapy Sensitivity

| Study | Biomarker |

|---|---|

| Metastatic setting | |

| MADeIt | ERCC1 |

| RRM1 | |

| Adjuvant setting | |

| SWOG 0720 | ERCC1 |

| RRM1 | |

| ITACA | ERCC1 |

| TS | |

| TASTE | EGFR activating mutation |

| ERCC1 | |

| GECP-SCAT | BRCA1 |

The clinical trial IALT demonstrated a 5-year OS benefit in 1867 patients treated in the adjuvant setting with cisplatin-based chemotherapy compared with observation.70 In a retrospective analysis of the ERCC1 immunohistochemistry on 761 tumors of patients treated in that study, adjuvant chemotherapy compared with observation significantly improved OS in patients with ERCC1-negative tumors (HR, 0.65; P = 0.002), but not in patients with ERCC1-positive tumors (HR, 1.14; P = 0.40).71 In the observation arm, patients with ERCC1-positive tumors survived longer than those with ERCC1-negative tumors (HR, 0.66; P = 0.009). Thus, ERCC1 appears to be both predictive of chemotherapy benefit and prognostic of clinical outcome.

Prospective validation is the subject of the ongoing SWOG0720 phase II clinical trial, which is evaluating the use of ERCC1 and RRM1 to guide therapy with cisplatin/gemcitabine in the adjuvant setting in patients with resected stage I NSCLC, with the primary outcome of feasibility and a secondary outcome of 2-year disease-free survival. The phase III ITACA clinical trial will accrue 700 patients with resected stage II to IIIA NSCLC and will randomize to either standard platinum-based chemotherapy or therapy selected on the basis of the expression of ERCC1 and thymidylate synthase (TS), a critical component of folate metabolism and a predictor of sensitivity to the antifolate drug, pemetrexed.72 In the TASTE clinical trial, patients with resected stage II to IIIA NSCLC are randomized to either standard chemotherapy or therapy based on the EGFR mutational status and ERCC1 expression. Patients randomized to the customized therapy arm with EGFR mutations are treated with erlotinib, whereas the remainder are treated on the basis of the level of ERCC1 expression (low-expression patients are treated with cisplatin/pemetrexed and high-expression patients are not treated) (Table 4).

BRCA1 is key to the repair of DNA double-strand breaks from cytotoxic chemotherapy,73 and the level of BRCA1 expression is prognostic in early-stage NSCLC.74 Low BRCA1 expression correlates with benefit from cisplatin-based chemotherapy, and high expression levels correlate with longer survival with taxane therapy.75 In the ongoing GECP-SCAT clinical trial, 432 patients with resected stage II to IIIA NSCLC are randomized to either standard chemotherapy or therapy selected on the basis of BRCA1 expression, with the primary end point of disease-free survival (Table 4).

CONCLUSIONS

In advanced NSCLC, the addition of bevacizumab is associated with a clear benefit with regard to PFS and, in E4599, OS. The EGFR TKIs are associated with superior PFS in the first-line setting in patients harboring sensitizing EGFR mutations. The evolution of resistance to EGFR TKIs necessitates the ongoing study of novel EGFR TKIs and combinations of EGFR TKIs with other molecularly targeted agents. Crizotinib in the treatment of patients with EML4-ALK rearrangements has resulted in unprecedented OS advantage, even in patients who have been heavily pretreated with multiple lines of therapy.

In the adjuvant setting, there are multiple ongoing clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of VEGF inhibitors and EGFR inhibitors in preventing disease recurrence, and there is intriguing work being done in the realm of cancer immunotherapy with the MAGE-A3 and MUC1 vaccines. These targeted agents do not negate the utility of chemotherapy but require a more refined approach to selecting the proper chemotherapeutic regimen for each individual patient. This realm of pharmacogenomic-driven personalized therapy might come to fruition with the conclusion of the multiple clinical trials being conducted in the adjuvant setting that are evaluating the role of ERCC1, RRM1, BRCA1, and TS.

Historically, NSCLC was treated as a single disease entity in both the metastatic and the adjuvant settings. With the evolving knowledge of the molecular aberrations in NSCLC, this disease should now be regarded as a compilation of molecularly distinct subtypes that should be treated as such with targeted agents and with the rational selection of chemotherapy guided by the pharmacogenetic characteristics of a patient’s tumor. Ongoing clinical trials and the development of novel agents are necessary to further advance the standard of care in the treatment of NSCLC.

Footnotes

Dr. Socinski reports receiving consulting fees from Lilly and Genentech. Dr. Villaruz has no commercial interests to disclose

References

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. [Accessed November 11, 2011];SEER stat fact sheets: Lung and bronchus. Available at: http://seercancergov/csr/1975_2008/

- 2.Herbst RS, Heymach JV, Lippman SM. Lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1367–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0802714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapp E, Pater JL, Willan A, et al. Chemotherapy can prolong survival in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Report of a Canadian multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:633–641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.4.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopwood P, Stephens RJ. Symptoms at presentation for treatment in patients with lung cancer: Implications for the evaluation of palliative treatment—The Medical Research Council (MRC) Lung Cancer Working Party. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:633–636. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 1995;311:899–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burdett S, Stewart L, Pignon J-P. Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: An update of an individual patient data-based meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:1205. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burdett S, Stephens R, Stewart L, et al. Chemotherapy in addition to supportive care improves survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 16 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4617–4625. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scagliotti GV, De Marinis F, Rinaldi M, et al. Phase III randomized trial comparing three platinum-based doublets in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4285–4291. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fossella F, Pereira JR, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized, multinational, phase III study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: The TAX 326 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3016–3024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: A Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3210–3218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zatloukal P, Petruzelka L, Zemanová M, et al. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin vs. gemcitabine plus carboplatin in stage IIIb and IV non-small cell lung cancer: A phase III randomized trial. Lung Cancer. 2003;41:321–331. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrara N. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in pathological angiogenesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;36:127–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00666035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattern J, Koomägi R, Volm M. Association of vascular endothelial growth factor expression with intratumoral microvessel density and tumour cell proliferation in human epidermoid lung carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:931–934. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown LF, Berse B, Jackman RW, et al. Expression of vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) and its receptors in adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4727–4735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown LF, Berse B, Jackman RW, et al. Expression of vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) and its receptors in breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:86–91. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seto T, Higashiyama M, Funai H, et al. Prognostic value of expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its flt-1 and KDR receptors in stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2006;53:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, et al. Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson DH, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny WF, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2184–2191. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, et al. Overall survival with cisplatin-gemcitabine and bevacizumab or placebo as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from a randomised phase III trial (AVAiL) Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1804–1809. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahlberg SE, Sandler AB, Brahmer JR, et al. Clinical course of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients experiencing hypertension during treatment with bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel on ECOG 4599. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:949–954. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–181. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukuoka M, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Biomarker analyses and final overall survival results from a phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in Asia (IPASS) J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2866–2874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J, Park K, Kim S-W, et al. A randomized phase III study of gefitnib (IRESSATM) versus standard chemotherapy (gemcitabine plus cisplatin) as a first-line treatment for never-smokers with advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Thoracic Oncol. 2009;4:S283. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosell R, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy (CT) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (p) with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations: Interim results of the European Erlotinib Versus Chemotherapy (EURTAC) phase III randomized trial. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2011;29:7503. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou C, Wu Y-L, Chen G, et al. Efficacy results from the randomised phase III Optimal (CTONG 0802) study comparing first-line erlotinib versus carboplatin (CBDCA) plus gemcitabine (GEM) in Chinese advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (PTS) with EGFR activating mutations. ESMO Late Breaking Abstracts. 2010;21:LBA13. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): An open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herbst RS, Prager D, Hermann R, et al. TRIBUTE: A phase III trial of erlotinib hydrochloride (OSI-774) combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5892–5899. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giaccone G, Herbst RS, Manegold C, et al. Gefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A phase III trial—INTACT 1. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:777–784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herbst RS, Giaccone G, Schiller JH, et al. Gefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A phase III trial—INTACT 2. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:785–794. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gatzemeier U, Pluzanska A, Szczesna A, et al. Phase III study of erlotinib in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: The Tarceva Lung Cancer Investigation Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1545–1552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pirker R, Pereira JR, Szczesna A, et al. Cetuximab plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (FLEX): An open-label randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1525–1531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynch TJ, Patel T, Dreisbach L, et al. Cetuximab and first-line taxane/carboplatin chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of the randomized multicenter phase III trial BMS099. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:911–917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herbst RS, Ansari R, Bustin F, et al. Efficacy of bevacizumab plus erlotinib versus erlotinib alone in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of standard first-line chemotherapy (BeTa): A double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1846–1854. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60545-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bean J, Brennan C, Shih JY, et al. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20932–20937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller V, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, et al. Phase IIB/III double-blind randomized trial of afatinib (BIBW 2992, an irreversible inhibitor of EGFR/HER1 and HER2) 1 best supportive care (BSC) versus placebo 1 BSC in patients with NSCLC failing 1–2 lines of chemotherapy and erlotinib or gefitinib (LUX-LUNG 1) Ann Oncol. 2010;21:LBA1. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiarle R, Voena C, Ambrogio C, et al. The anaplastic lymphoma kinase in the pathogenesis of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561–566. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soda M, Takada S, Takeuchi K, et al. A mouse model for EML4-ALK-positive lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19893–19897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805381105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4247–4253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Ana-plastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Solomon BJ, et al. Impact of crizotinib on survival in patients with advanced, ALK-positive NSCLC compared with historical controls. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2011;29:7507. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goss GD, Lorimer I, Tsao MS, et al. A phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor gefitinb in completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): NCIC CTG BR.19. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2010;28:LBA7005. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raez LE, Fein S, Podack ER. Lung cancer immunotherapy. Clin Med Res. 2005;3:221–228. doi: 10.3121/cmr.3.4.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abu-Shakra M, Buskila D, Ehrenfeld M, et al. Cancer and autoimmunity: Autoimmune and rheumatic features in patients with malignancies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:433–441. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.5.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Novellino L, Castelli C, Parmiani G. A listing of human tumor antigens recognized by T cells: March 2004 update. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:187–207. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pardoll D. Does the immune system see tumors as foreign or self? Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:807–839. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hirschowitz EA, Hiestand DM, Yannelli JR. Vaccines for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:93–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Plaen E, Arden K, Traversari C, et al. Structure, chromosomal localization, and expression of 12 genes of the MAGE family. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:360–369. doi: 10.1007/BF01246677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vansteenkiste J, Zielinski M, Linder A, et al. Final results of a multi-center, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase II study to assess the efficacy of MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic as adjuvant therapy in stage IB/II non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2007;25:7554. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ho SB, Niehans GA, Lyftogt C, et al. Heterogeneity of mucin gene expression in normal and neoplastic tissues. Cancer Res. 1993;53:641–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Butts C, Murray N, Maksymiuk A, et al. Randomized phase IIB trial of BLP25 liposome vaccine in stage IIIB and IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6674–6681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mu D, Hsu DS, Sancar A. Reaction mechanism of human DNA repair excision nuclease. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8285–8294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sancar A. Mechanisms of DNA excision repair. Science. 1994;266:1954–1956. doi: 10.1126/science.7801120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zamble DB, Mu D, Reardon JT, et al. Repair of cisplatinDNA adducts by the mammalian excision nuclease. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10004–10013. doi: 10.1021/bi960453+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosell R, Danenberg KD, Alberola V, et al. Ribonucleotide reductase messenger RNA expression and survival in gemcitabine/cisplatin-treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1318–1325. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davidson JD, Ma L, Flagella M, et al. An increase in the expression of ribonucleotide reductase large subunit 1 is associated with gemcitabine resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3761–3766. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bergman AM, Eijk PP, Ruiz van Haperen VW, et al. In vivo induction of resistance to gemcitabine results in increased expression of ribonucleotide reductase subunit M1 as the major determinant. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9510–9516. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bepler G, Kusmartseva I, Sharma S, et al. RRM1 modulated in vitro and in vivo efficacy of gemcitabine and platinum in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4731–4737. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simon G, Sharma A, Li X, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of molecular analysis-directed individualized therapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2741–2746. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, et al. Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:351–360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Olaussen KA, Dunant A, Fouret P, et al. DNA repair by ERCC1 in non-small-cell lung cancer and cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:983–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takezawa K, Okamoto I, Okamoto W, et al. Thymidylate synthase as a determinant of pemetrexed sensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:1594–1601. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Anders CK, Winer EP, Ford JM, et al. Poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition: “Targeted” therapy for triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4702–4710. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taron M, Rosell R, Felip E, et al. BRCA1 mRNA expression levels as an indicator of chemoresistance in lung cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2443–2449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quinn JE, James CR, Stewart GE, et al. BRCA1 mRNA expression levels predict for overall survival in ovarian cancer after chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7413–7420. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.O’Byrne KJ, Bondarenko I, Barrios C, et al. Molecular and clinical predictors of outcome for cetuximab in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Data from the FLEX study. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2009;27:8007. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Douillard JY, Shepherd FA, Hirsh V, et al. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib and docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer: Data from the randomized phase III INTEREST trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:744–752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kawano O, Sasaki H, Endo K, et al. PIK3CA mutation status in Japanese lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2006;54:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yamamoto H, Shigematsu H, Nomura M, et al. PIK3CA mutations and copy number gains in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6913–6921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Onozato RMD, Kosaka TMD, Kuwano HMD, et al. Activation of MET by gene amplification or by splice mutations deleting the juxtamembrane domain in primary resected lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:5–11. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181913e0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Paik PK, Arcila ME, Fara M, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2046–2051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dziadziuszko R, Merrick DT, Witta SE, et al. Insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF1R) gene copy number is associated with survival in operable non-small-cell lung cancer: A comparison between IGF1R fluorescent in situ hybridization, protein expression, and mRNA expression. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2174–2180. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lynch TJ, Patel T, Dreisbach L, et al. Cetuximab and first-line taxane/carboplatin chemotherapy in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: Results of the randomized multicenter phase III trial BMS099. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:911–917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Crino L, Kim D, Riely GJ, et al. Initial phase II results with crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): PROFILE 1005. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2011;29:7514. [Google Scholar]