ABSTRACT

A novel chimeric parvoviral vector, rAAV2/HBoV1, in which the recombinant adeno-associated virus 2 (rAAV2) genome is pseudopackaged by the human bocavirus 1 (HBoV1) capsid, has been shown to be highly efficient in gene delivery to human airway epithelia (Z. Yan et al., Mol Ther 21:2181–2194, 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/mt.2013.92). In this vector production system, we used an HBoV1 packaging plasmid, pHBoV1NSCap, that harbors HBoV1 nonstructural protein (NS) and capsid protein (Cap) genes. In order to simplify this packaging plasmid, we investigated the involvement of the HBoV1 NS proteins in capsid protein expression. We found that NP1, a small NS protein encoded by the middle open reading frame, is required for the expression of the viral capsid proteins (VP1, VP2, and VP3). We also found that the other NS proteins (NS1, NS2, NS3, and NS4) are not required for the expression of VP proteins. We performed systematic analyses of the HBoV1 mRNAs transcribed from the pHBoV1NSCap packaging plasmid and its derivatives in HEK 293 cells. Mechanistically, we found that NP1 is required for both the splicing and the read-through of the proximal polyadenylation site of the HBoV1 precursor mRNA, essential functions for the maturation of capsid protein-encoding mRNA. Thus, our study provides a unique example of how a small viral nonstructural protein facilitates the multifaceted regulation of capsid gene expression.

IMPORTANCE A novel chimeric parvoviral vector, rAAV2/HBoV1, expressing a full-length cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, is capable of correcting CFTR-dependent chloride transport in cystic fibrosis human airway epithelium. Previously, an HBoV1 nonstructural and capsid protein-expressing plasmid, pHBoV1NSCap, was used to package the rAAV2/HBoV1 vector, but yields remained low. In this study, we demonstrated that the nonstructural protein NP1 is required for the expression of capsid proteins. However, we found that the other four nonstructural proteins (NS1 to -4) are not required for expression of capsid proteins. By mutating the cis elements that function as internal polyadenylation signals in the capsid protein-expressing mRNA, we constructed a simple HBoV1 capsid protein-expressing gene that expresses capsid proteins as efficiently as pHBoV1NSCap does, and at similar ratios, but independently of NP1. Our study provides a foundation to develop a better packaging system for rAAV2/HBoV1 vector production.

INTRODUCTION

Human bocavirus 1 (HBoV1), first identified in 2005 (1), belongs to the genus Bocaparvovirus in the subfamily Parvovirinae of the family Parvoviridae (2). The genus Bocaparvovirus consists of three groups of viruses, namely, HBoV1 to -4, bovine parvovirus 1 (BPV1), and minute virus of canines (MVC/CnMV) (3). HBoV1 causes respiratory tract infections in young children worldwide (4–11). In vitro, the virus infects only polarized (well-differentiated) human airway epithelium cultured at an air-liquid interface (HAE-ALI) (12–15). We have constructed an infectious clone of HBoV1 (pIHBoV1). Transfecting pIHBoV1 in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cells results in efficient replication of the HBoV1 genome and production of HBoV1 virions, which are infectious in HAE-ALI (13, 14).

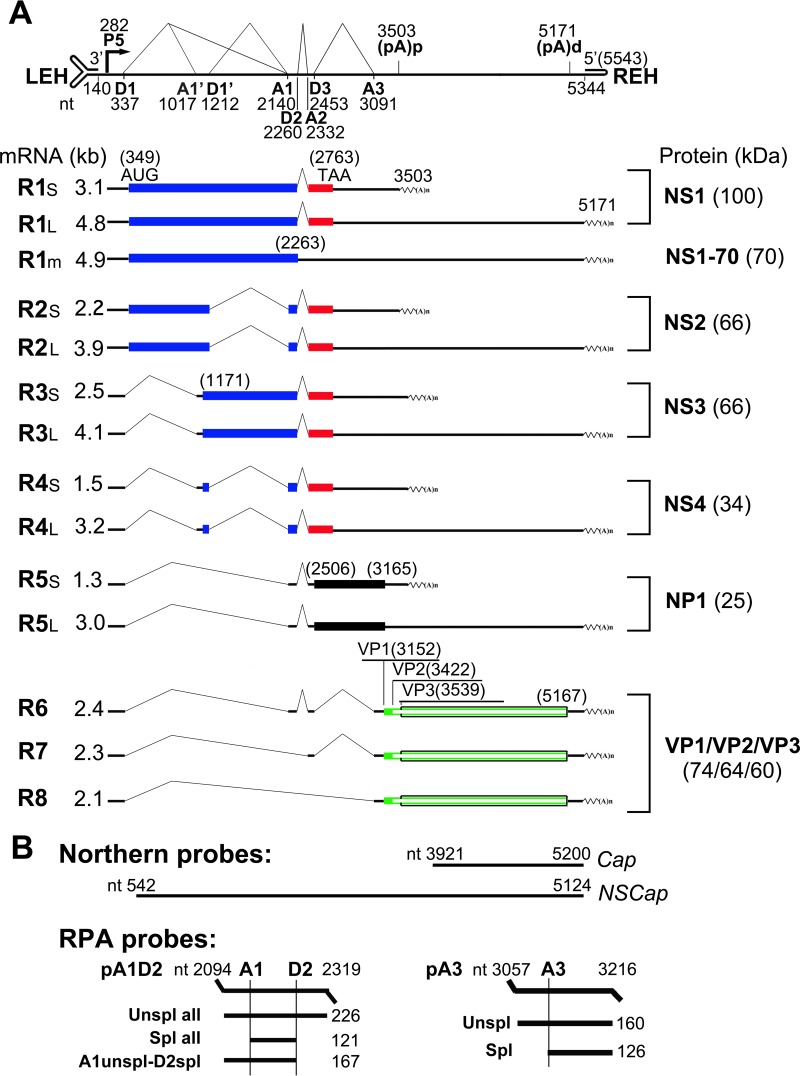

The transcription profile of HBoV1 has been studied in transfection of both HBoV1 nonreplicating and replicating double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) forms of the viral genome in HEK 293 cells (16, 17), as well as during HBoV1 infection of HAE-ALI (12, 17). All the viral mRNA transcripts are generated from both alternative splicing and alternative polyadenylation of one HBoV1 precursor mRNA (pre-mRNA), which is transcribed from the P5 promoter (Fig. 1A) (12, 16, 17). The left side of the genome encodes nonstructural (NS) proteins, and four major NS proteins (NS1, NS2, NS3, and NS4) are expressed from alternatively spliced mRNA transcripts (17). While NS1 is critical to viral DNA replication, NS2 also plays a role in virus replication of HAE-ALI (17). The right side of the genome encodes viral capsid proteins from alternatively spliced mRNA transcripts, R6, R7, and R8 mRNAs (Fig. 1A). Of note, HBoV1, like other members of the genus Bocaparvovirus, encodes a unique nonstructural protein, NP1, from the middle of the genome. NP1 is required for efficient replication of viral DNA (13, 18).

FIG 1.

Genetic map of HBoV1 and the probes used. (A) The expression profiles of HBoV1 mRNA transcripts and their encoded proteins are shown with transcription landmarks and boxed ORFs. The numbers are nucleotide numbers of the HBoV1 full-length genome (GenBank accession no. JQ923422). Major species of HBoV1 mRNA transcripts that are alternatively processed are shown with their sizes in kilobases [minus a poly(A) tail of ∼150 nt], which were derived from multiple studies of HBoV1 DNA transfection of HEK 293 cells and HBoV1 infection of polarized human airway epithelium (12, 16, 17). Viral proteins detected in both transfected and infected cells are shown side by side on the right. P5, P5 promoter; D, 5′ splice donor site; A, 3′ splice acceptor site; (pA)p and (pA)d, proximal (internal) and distal polyadenylation sites, respectively; LEH/REH, left-end/right-end hairpins. (B) Probes used for Northern blot analysis with nucleotide numbers. The probes used for the RPA are diagrammed with the sizes of their detected bands.

HBoV1 capsid is capable of cross-genus packaging of a genome of recombinant adeno-associated virus 2 (rAAV2) in HEK 293 cells. This cross-genus packaging generates an HBoV1 capsid-pseudotyped rAAV2 vector (rAAV2/HBoV1) (19). The chimeric vector can deliver a full-length cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene with a strong promoter to cystic fibrosis (CF) HAE, with demonstrated efficacy in correcting CFTR-dependent chloride transport (19). The rAAV2/HBoV1-CFTR vector therefore holds much promise for CF gene therapy. However, in the current vector production system, the vector is packaged using the packaging plasmid pHBoV1NSCap, which carries an HBoV1 nonreplicating dsDNA genome (containing the P5 promoter and NS and capsid protein [Cap] genes). The efficiency of the vector production is on average 10 times lower than that of the rAAV2 vector packaged by the AAV2 capsid (19). We hypothesize that this lower efficiency is likely due to the unnecessary expression of the HBoV1 NS gene from the packaging plasmid, pHBoV1NSCap.

To improve the packaging efficiency of rAAV2/HBoV1 vector HEK 293 cells, we studied the expression of the HBoV1 capsid proteins. We found that expression of HBoV1 capsid proteins is regulated by NP1, but not by NS1, NS2, NS3, or NS4. Without NP1, HBoV1 capsid protein-encoding transcripts are expressed at a low level that is not sufficient for the expression of capsid proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

The parent plasmid pHBoV1NSCap has been used to package the rAAV2/HBoV1 vector, which contains an incomplete HBoV1 genome (nucleotides [nt] 97 to 5395) that lacks the intact left- and right-end hairpins (19). All the other plasmids based on the pHBoV1NSCap were constructed as described below, and they are also diagrammed in the figures.

pHBoV1NSCap-based plasmids.

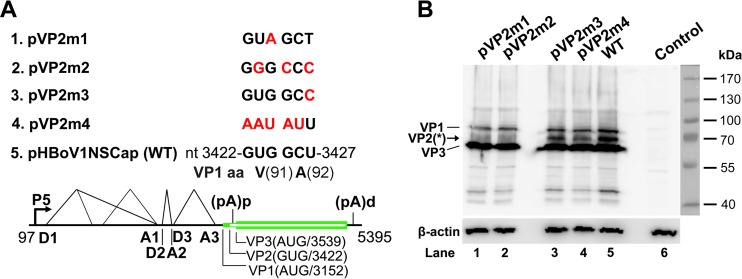

pVP2m1, pVP2m2, pVP2m3, and pVP2m4 were constructed by mutating nt 3422 to 3427 of the HBoV1 sequence (see Fig. 3A) in pHBoV1NSCap.

FIG 3.

VP2 is translated from a noncanonical translation initiation codon. (A) Diagrams of pHBoV1NSCap-based mutants. The parent pHBoV1NSCap plasmid is diagrammed with transcription, splicing, and polyadenylation units shown, together with the mutants that carry various mutations at the GUG and GCU codons (nt 3422 to 3427) of the HBoV1 genome, as indicated (red). (B) Western blot analysis of capsid proteins. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. The lysates of the transfected cells were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-VP antibody and reprobed with anti-β-actin. The identities of the detected bands are indicated at the left of the blot. The arrow shows the novel VP2 protein, which was denoted previously by an asterisk (17). Control, without transfection.

pCMVNSCap-based plasmids.

pCMVNSCap was constructed by replacing the HBoV1 P5 promoter (nt 97 to 281) with the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early enhancer/promoter sequence retrieved from the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Grand Island, NY) in pHBoV1NSCap. pCMVNSCapbGHpA was constructed by replacing the HBoV1 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (nt 5168 to 5395) with the bovine hormone gene polyadenylation signal (bGHpA) of pcDNA3 in pCMVNSCap. Based on pCMVNSCap, we terminated NS1-, NP1-, and both NS1- and NP1-encoding sequences early by introducing a stop codon (13), which allowed us to construct pCMVNS*Cap, pCMVNS(NP*)Cap, and pCMVNS*(NP*)Cap, respectively.

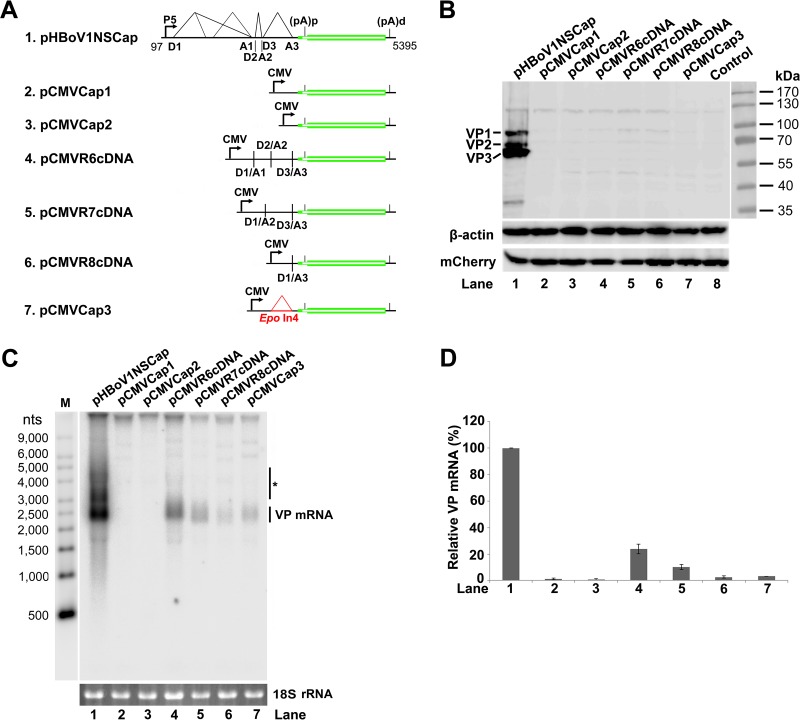

VP cDNA plasmids.

VP cDNA plasmids were derived from pCMVNSCap. We deleted nt 337 to 3091 of the HBoV1 sequence in the parent plasmid to construct pCMVCap1; further deletion of nt 282 to nt 3151, which left the VP1 open reading frame (ORF) directly under the CMV promoter, resulted in construct pCMVCap2. We deleted all the D1-A1, D2-A2, and D3-A3 intron sequences to construct pCMVR6cDNA. We removed the D1-A2 and D3-A3 intron sequences to construct pCMVR7cDNA. We removed the D1-A3 intron sequence to construct pCMVR8cDNA. These three cDNA constructs correlate with three VP-encoding mRNA transcripts, R6, R7, and R8 mRNAs, which we previously identified (Fig. 1A).

Plasmids with introns replaced.

We inserted the erythropoietin gene (Epo) intron 4 (20) between the D1 and A3 sites to construct pCMVCap3. Based on the pCMVNS*Cap plasmid, we deleted the D3-A3 intron sequence to construct pCMVNS*(In3Δ)Cap. Based on pCMVNS*(In3Δ)Cap, we changed the first and second introns to Epo introns 1 and 4, respectively, to construct pCMVEpoIn14(In3Δ)Cap. Additionally, we changed all three introns in pCMVNSCap to Epo introns 1, 2, and 4 to construct pCMVEpoIn124Cap.

Proximal polyadenylation site [(pA)p] knockout [m(pA)p] constructs.

We silently mutated the five polyadenylation sites (PASs) potentially used and both their upstream and downstream elements [m(pA)p], which span the coding region for the amino acids between methionines of the VP1 and VP3 ORFs, through a codon optimization algorithm at Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA (IDT) (Fig. 2). We used an optimized Kozak sequence (GTT AAG ACG) to express VP1 and retained the GTG codon for VP2 in order to obtain an appropriate ratio of VP1 to VP2 and to VP3. To construct pCMVNS*(NP*)m(pA)pCap and pCMVNS*(In3Δ)m(pA)pCap, we mutated the (pA)p sites in pCMVNS*(NP*)Cap and pCMVNS*(In3Δ)Cap, respectively. In the pCMVR6-8cDNA constructs, we mutated the (pA)p sites to make pCMVR6-8cDNAm(pA)p.

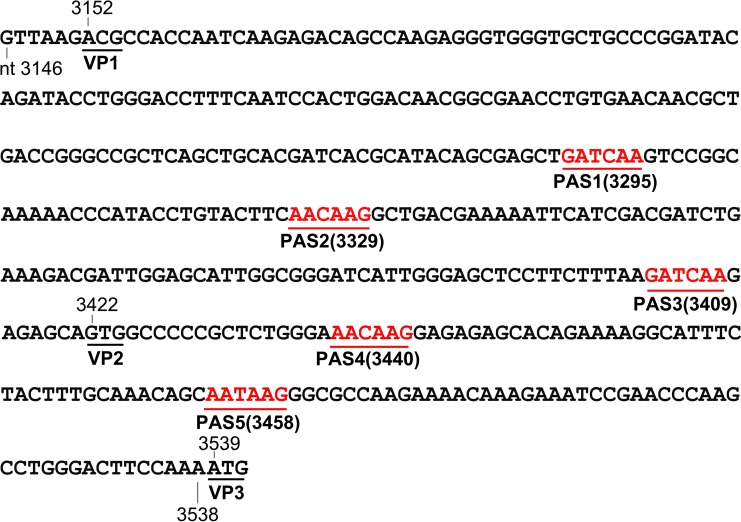

FIG 2.

DNA sequences of silent mutations in the (pA)p sites. Nucleotide sequences between the VP1 and VP3 start codons were silently mutated to eliminate potentially used (cryptic) PASs (AAUAAA) but still retain the same coding amino acid sequence as the wild type. The mutated sequence is shown with the locations of the 5 PASs (red). The VP1 start codon was mutated from ATG to ACG, together with a weak Kozak signal (GTT AAG), and retained the VP2 start codon, GTG.

Other plasmids.

pOpt-NP1 was constructed by inserting a codon-optimized NP1 ORF, which was synthesized at IDT, into the pLenti-CMV-IRES-GFP-WPRE vector (21) through XbaI and BamHI sites. pCI-mCherry-HA was constructed by inserting a C-terminally hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged mCherry ORF into the pCI vector (Promega, Madison, WI) through XhoI and XbaI sites.

All nucleotide numbers of the HBoV1 genome refer to the full-length HBoV1 genome (GenBank accession no. JQ923422). The constructs were verified for HBoV1 sequence and mutations by Sanger sequencing at MCLAB (South San Francisco, CA).

Cell culture and transfection.

HEK 293 cells (CRL-1573) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA) and were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) with 10% fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Cells grown in 60-mm dishes were transfected with a total of 4 μg of plasmid DNA using LipoD293 reagent (SignaGen Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD), following the manufacturer's instructions. The pLenti-CMV-IRES-GFP-WPRE vector (21) was cotransfected into HEK 293 cells to ensure the same amount of plasmid DNA was transfected for each NP1 complementation experiment. As a control for transfection, 0.4 μg of pCI-mCherry-HA plasmid DNA was cotransfected into HEK 293 cells.

Western blotting.

HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated in each figure. The cells were harvested and lysed 2 days posttransfection. Western blotting was performed to analyze the lysates as previously described (16), using the specific antibodies described in each figure legend. Rat anti-HBoV1 VP, NP1, and NS1 C terminus (NS1C) were produced previously (16). Anti-β-actin and anti-HA monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

RNA isolation and analyses. (i) RNA isolation.

Cytoplasmic RNA was purified from transfected cells following the Qiagen supplementary protocol using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). For the RNA samples used to examine RNA export, the same numbers of cells were extracted for cytoplasmic RNA and total RNA using the RNeasy minikit. Other total-RNA samples were prepared using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

(ii) Northern blotting.

Five micrograms of cytoplasmic or total RNA was separated on a 1.4% denaturation agarose gel and visualized using ethidium bromine (EB) staining. The stained 18S rRNA bands served as loading controls. Northern blot analysis was performed as previously described (18), using 32P-labeled DNA probes as diagrammed in Fig. 1B. In some gels, an RNA ladder (Invitrogen) was used as a size marker (22).

(iii) RPA.

We performed the RNase protection assay (RPA) as described previously (16, 18). RPA probes pA1D2 and pA3 were constructed by cloning HBoV1 sequences (nt 2094 to 2319 and nt 3057 to 3216, respectively) into the BamHI/HindIII-digested vector pGEM4Z (Promega). The protected bands detected by the pA1D2 and pA3 probes are diagrammed in Fig. 1B.

(iv) Quantification.

Images of both Northern blotting and RPA were processed using a GE Typhoon FLA 9000 phosphorimager (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA). ImageQuant TL 8.1 software was used to quantify the bands on the images.

RESULTS

Identification of a noncanonical initiation site that encodes a novel capsid protein of VP2.

We previously detected a band of capsid protein (VP*) whose size is between those of VP1 and “VP2” in HBoV1-infected human airway epithelium and HBoV1 plasmid-transfected HEK 293 cells (17), as well as in the purified rAAV2/HBoV1 vector (19). However, we did not know whether this VP* band was a cleaved protein of VP1 or a novel capsid protein translated from a noncanonical initiation site. A GCU codon of the alanine at amino acid (aa) 92 of the VP1 ORF has been identified as an initiation codon in the expression of the VP1 ORF in insect Sf9 cells (23). Therefore, we examined this initiation site in the expression of HBoV1 capsid proteins in HEK 293 cells. We made four mutations in the GUG and GCU codons in pHBoV1NSCap (Fig. 3A). Two mutants that bear mutations of the GUG codon, which encode the valine of aa 91 of the VP1 ORF, drastically decreased expression of the intermediate band between VP1 and VP3 (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 2). Thus, we confirmed that this intermediate band (VP*) of the HBoV1 capsid proteins is a novel capsid protein of VP2 initiated at the GUG codon at nt 3422 of the HBoV1 genome.

HBoV1 VP cDNA is intrinsically inefficient at generating VP-encoding mRNA.

In the rAAV2/HBoV1 vector production system, a nonreplicating HBoV1 construct, pHBoV1NSCap, was used as a packaging plasmid (19), which expressed NS1 to -4 and NP1 (17) in addition to capsid proteins. To identify a simple packaging plasmid that expresses only capsid proteins, we attempted to express HBoV1 capsid proteins ectopically with a minimal HBoV1 sequence containing the VP ORFs. To this end, six VP expression plasmids under the control of the CMV promoter, as outlined in Fig. 4A, were constructed, including three VP cDNA constructs of R6, R7, and R8 mRNAs (Fig. 1A) and the other three VP ORF constructs that contain various 5′ UTR sequences. To our surprise, none of them expressed capsid proteins in transfected HEK 293 cells, as detected by Western blotting (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 to 7). We next performed Northern blotting to analyze VP-encoding mRNA in the cytoplasm using a VP mRNA-specific Cap probe (Fig. 1B). We detected only a low abundance of the VP mRNA in the cytoplasmic RNA preparations of the cells transfected with the three cDNA constructs and pCMVCap3. This VP mRNA was less than ∼20% of the VP mRNA generated from the control pHBoV1NSCap (Fig. 4C and D, lanes 4 to 7). We detected almost no cytoplasmic VP mRNA from the cells transfected with pCMVCap1 and pCMVCap2 (Fig. 4C and D, lanes 2 and 3).

FIG 4.

HBoV1 VP cDNA constructs did not express capsid proteins. (A) Diagrams of HBoV1 VP cDNA constructs. pHBoV1NSCap is diagrammed with transcription, splicing, and polyadenylation units shown. pCMVCap1-3 and pCMVR6-8cDNA, which contain various sequences of the 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR and the VP1/2/3 ORF, are diagrammed with the junction of the 5′ and 3′ splice sites or the heterogeneous Epo intron 4 (Epo In4), as indicated. (B) Western blot analysis of capsid proteins. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. The lysates of the transfected cells were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-VP antibody and reprobed with anti-β-actin. The lysates were also analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-HA antibody to detect the C-terminally HA-tagged mCherry. The identities of the detected bands are indicated on the left of the blot. (C) Northern blot analysis of cytoplasmic VP mRNAs. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. Cytoplasmic RNA prepared from each transfection was analyzed by Northern blotting using the Cap probe, which specifically detects VP mRNA (Fig. 1B). EB-stained 18S rRNA bands are shown, and the VP mRNA band is indicated. The asterisk denotes various NS-encoding mRNAs. An RNA ladder (M) was used as a size marker. (D) Quantification of VP mRNA expression. The bands of VP mRNA in each lane of panel C were quantified and normalized to the level of 18S rRNA. The signal intensity of the VP mRNA band in lane 1 was arbitrarily set as 100%. Relative intensities were calculated for the bands in the other lanes. Means and standard deviations were calculated from the results of at least three independent experiments.

Taken together, these results revealed that ectopic expression of the HBoV1 VP ORF is not sufficient to express capsid proteins, due to the poor production of VP mRNA in the cytoplasm.

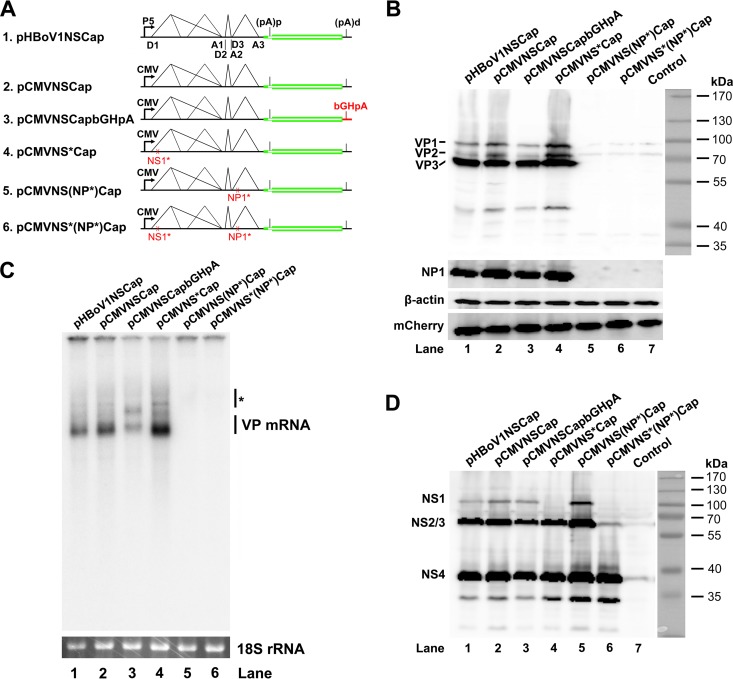

The NP1 protein plays an important role in the expression of capsid proteins.

We next investigated how the capsid proteins are expressed from pHBoV1NSCap. To systematically explore the effects of the cis elements of the viral genome and of the viral proteins in trans on the expression of capsid proteins, we made five constructs, as shown in Fig. 5A. Exchange of either the P5 promoter with the CMV promoter or the 3′ UTR with bGHpA did not affect capsid protein expression in general (Fig. 5B, lanes 2 and 3 versus 1). Knockout of NS1 and NS2 expression in pCMVNSCap (Fig. 5D, lane 4, NS1) did not diminish the levels of capsid proteins (Fig. 5B, lane 4, VP). However, when we knocked out NP1 expression by early termination of the NP1 ORF, both NP1 knockout constructs, pCMVNS(NP*)Cap and pCMVNS*(NP*)Cap, failed to express appreciable levels of capsid proteins (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 and 6). We next examined the levels of the cytoplasmic VP mRNA in transfected cells. Consistent with the capsid protein expression, NP1 knockout nearly abolished VP mRNA in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5C, lanes 5 and 6).

FIG 5.

Knockout of NP1 abolished VP mRNA production and capsid protein expression. (A) Diagrams of HBoV1 NSCap gene constructs. pHBoV1NSCap and its derivatives are diagrammed with replacement of the CMV promoter and bGHpA signal and knockout of NS1 and NP1, as indicated. (B) Western blot analysis of capsid proteins. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. The cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-VP antibody. The blot was reprobed with anti-β-actin. The lysates were also analyzed by Western blotting using anti-NP1 and anti-HA (for mCherry) antibodies. The identities of the detected proteins are shown at the left of the blot. (C) Northern blot analysis of cytoplasmic VP mRNAs. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. The cells were harvested, and cytoplasmic RNA was extracted 2 days posttransfection. The cytoplasmic RNA samples were analyzed by Northern blotting using the Cap probe. EB-stained 18S rRNA and detected VP mRNA are indicated. The asterisk denotes various NS-encoding mRNAs. (D) Western blot analysis of NS proteins. The same lysates prepared for panel B were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-NS1C antibody. The identities of the detected NS proteins are shown on the left of the blot.

Collectively, these results provided evidence that HBoV1 NP1 plays a critical role in the expression of capsid proteins, which is due to the increased level of VP mRNA in the cytoplasm. In addition, these results showed that NS1 and NS2 proteins in trans and the cis sequences of the P5 promoter and the 3′ UTR are not essential to capsid protein expression.

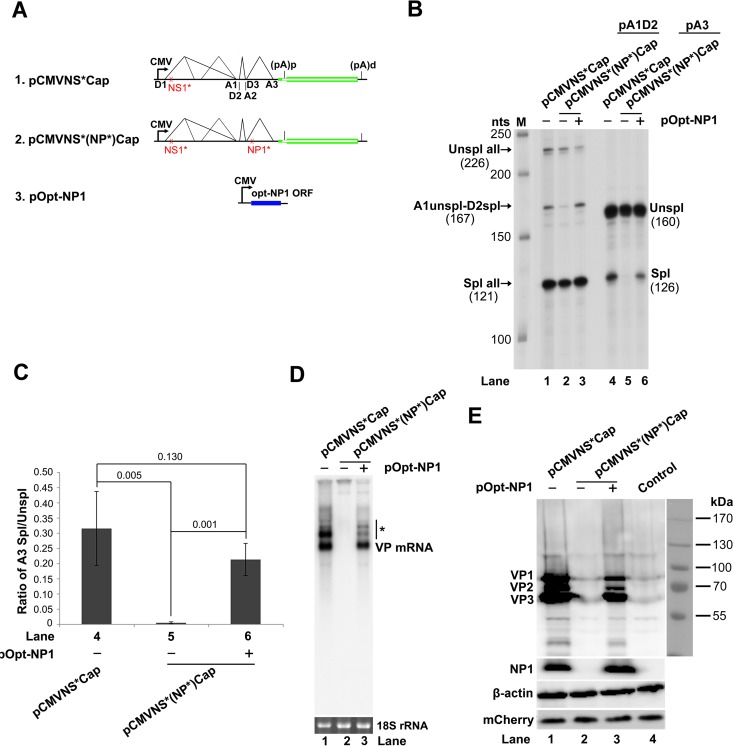

NP1 protein facilitates splicing of VP mRNA at the A3 splice acceptor.

We next studied how NP1 regulates capsid protein expression. Since splicing at the A3 splice acceptors of the three introns is a prerequisite for the production of VP-encoding R6, R7, and R8 mRNA transcripts (Fig. 1A), we examined the function of NP1 in the splicing at the A3 splice acceptor. When NP1 was knocked out, splicing at the A3 splice acceptor decreased by 78-fold (Fig. 6B, lane 5 versus 4), whereas the splicing of the first and second introns did not change very much (Fig. 6B, lane 2 versus 1). Complementation of NP1 in trans restored 67% of the mRNA spliced at the A3 splice acceptor (Fig. 6B and C, lane 6 and bar 6). In parallel with the inefficient splicing at the A3 splice acceptor, cytoplasmic VP mRNA was not detectable (Fig. 6D, lane 2), and capsid proteins were not expressed from pCMVNS*(NP*)Cap (Fig. 6E, lane 2). However, complementation of NP1 restored the expression of both VP mRNA and capsid proteins (Fig. 6D and E, lanes 3).

FIG 6.

NP1 complementation rescued VP mRNA production and capsid protein expression. (A) Diagrams of HBoV1 NSCap constructs. pCMVNS*Cap and pCMVNS*(NP*)Cap are diagrammed, along with the pOpt-NP1 plasmid that expresses NP1 from a codon-optimized NP1 ORF. (B) RPA analysis of viral RNAs spliced at the A1, D2, and A3 splice sites. Ten micrograms of total RNA isolated 2 days posttransfection from HEK 293 cells transfected with plasmids as indicated was protected by both the pA1D2 and pA3 probes. Lane M, 32P-labeled RNA markers (22), with sizes indicated on the left. The origins of the protected bands in the lanes are indicated on the left and right for the pA1D2 and pA3 probes, respectively. Spl, spliced RNAs; Unspl, unspliced RNAs. (C) Quantification of the mRNAs spliced at the A3 splice acceptor. The bands of both spliced and unspliced RNAs in lanes 4 to 6 of panel B were quantified. The ratio of spliced versus unspliced RNA (A3 Spl/Unspl) was calculated and is shown with means and standard deviations from three independent experiments. The numbers shown are P values calculated using a two-tailed Student t test. (D) Northern blot analysis of cytoplasmic VP mRNAs. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated and harvested 2 days posttransfection. Cytoplasmic RNA was extracted, and the RNA samples were analyzed by Northern blotting using the Cap probe. EB-stained 18S rRNA and VP mRNA are indicated. The asterisk denotes various NS-encoding mRNAs. (E) Western blot analysis of capsid proteins. Transfected cells were harvested and lysed 2 days posttransfection. The lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-VP antibody. The blot was reprobed with anti-β-actin. The lysates were also analyzed by Western blotting using anti-NP1 and anti-HA (for mCherry) antibodies. The identities of detected proteins are shown at the left of the blot.

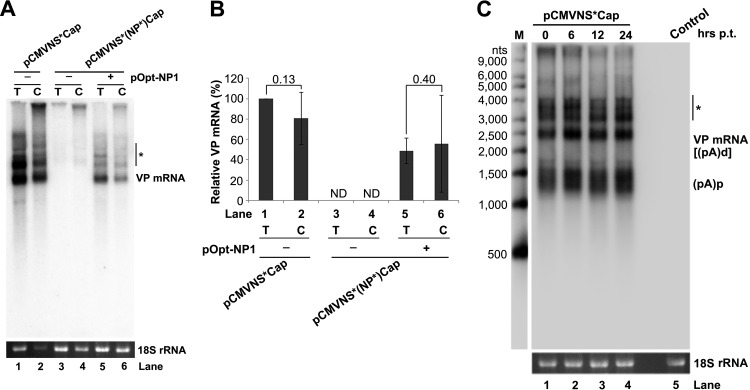

The undetectable level of cytoplasmic mRNA from the NP1 knockout mutant, therefore, was due to the inhibited production of VP mRNA in the nucleus and not to the inefficient export of VP mRNA from the nucleus (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 3 and 4). VP mRNA was exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm efficiently (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 1 versus 2 and 5 versus 6). In addition, VP mRNA was quite stable in the cells for a period of 24 h, as determined by an RNA stability assay using actinomycin D (Fig. 7C).

FIG 7.

HBoV1 VP mRNA was exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm efficiently and was stable. (A) Northern blot analysis. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids, as indicated, with (+) or without (−) cotransfection of pOpt-NP1. The same numbers of cells were harvested and extracted for both total (T) and cytoplasmic (C) RNA. The RNA samples were analyzed by Northern blotting using the Cap probe. EB-stained 18S rRNA and VP mRNA are indicated. The asterisk denotes various NS-encoding mRNAs. (B) Quantification of VP mRNAs on a Northern blot. The bands of VP mRNA in each lane of panel A were quantified and normalized to the level of 18S rRNA. The intensity of the VP mRNA band in lane 1 was arbitrarily set as 100%. The relative VP mRNA levels were calculated for the bands in the other lanes. Means and standard deviations were quantified from the results of three independent experiments. The P values shown were calculated using a two-tailed Student t test. ND, not detectable. (C) RNA stability assay. HEK 293 cells were transfected with pCMVNS*Cap. At 2 days postinfection, the cells were treated with actinomycin D at 5 μg/ml for the times (hrs p.t. [posttransfection]) indicated. The treated cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted. The RNA samples were analyzed by Northern blotting using the NSCap probe (Fig. 1B). EB-stained 18S rRNA bands are shown. The indicated bands are detected VP mRNA at ∼2.5 kb, which is likely the R6 mRNA that is polyadenylated at the (pA)d site, and (pA)p mRNA at ∼1.5 kb, which is the R5s mRNA that is polyadenylated at the (pA)p site (Fig. 1A). The asterisk denotes various NS-encoding mRNAs. Control, total RNA of nontransfected cells.

Taken together, these results confirmed that NP1 is required for the splicing of HBoV1 mRNAs at the A3 splice acceptor, which determines the level of VP mRNA in the cytoplasm and therefore the production of capsid proteins.

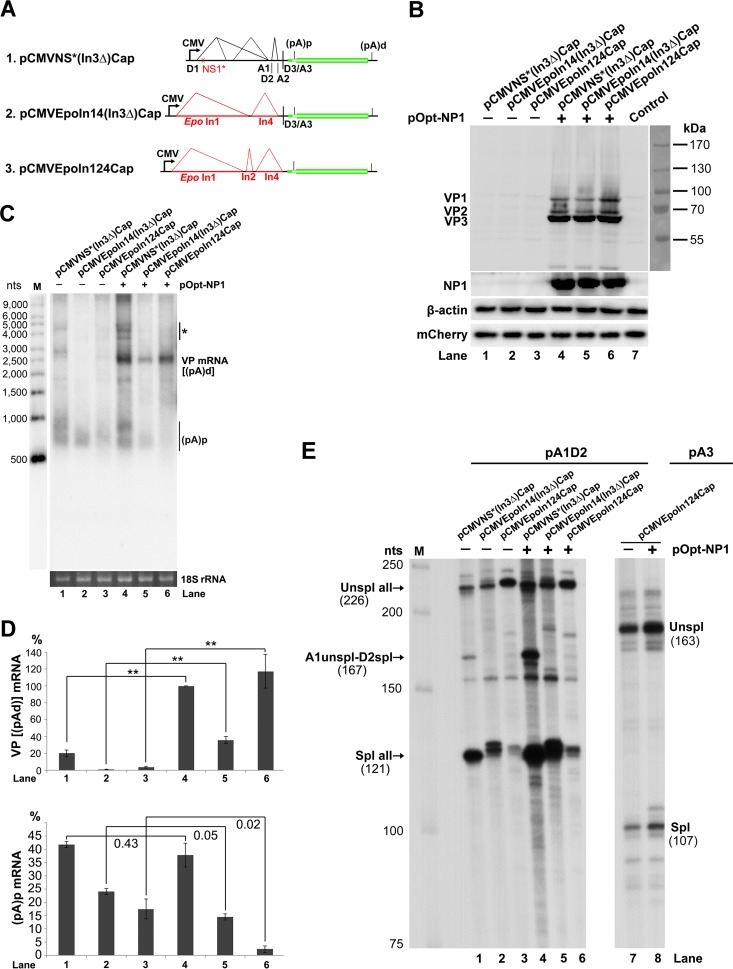

NP1 protein activates VP mRNA expression independently of splicing.

To distinguish the function of NP1 in splicing and internal polyadenylation of HBoV1 pre-mRNA, we constructed three helper plasmids: (i) pCMVNS*(In3Δ)Cap, in which the third intron was removed; (ii) pCMVEpoIn14(In3Δ)Cap, in which the first and second introns were replaced with Epo introns 1 and 4, respectively, and the third intron was also removed; and (iii) pCMVEpoIn124Cap, in which all three introns were replaced with Epo introns (Fig. 8A). Since the NP1 protein was encoded by the ORF in the third intron sequence, all three constructs did not express NP1 (Fig. 8B, lanes 1 to 3). When NP1 was added back in trans, VP mRNA at ∼2.5 kb, which is likely the R6 mRNA that reads through the (pA)p site and is polyadenylated at the (pA)d site (Fig. 1A), increased by at least 5-fold {Fig. 8C and D, VP [(pA)d] mRNA}. However, the (pA)p mRNA at ∼0.8 kb, which is spliced at all introns and polyadenylated at the (pA)p site, either remained unchanged or was not significantly decreased [Fig. 8C and D, (pA)p mRNA].

FIG 8.

NP1 increased VP mRNA production independently of RNA splicing at the A3 splice acceptor. (A) HBoV1 intron deletion/exchange constructs. Plasmids pCMVNS*(In3Δ)Cap, pCMVEpoIn14(In3Δ)Cap, and pCMVEpoIn124Cap are diagrammed, with replaced introns shown. (B) Western blot analysis of capsid proteins. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids, as indicated, with (+) or without (−) cotransfection of pOpt-NP1. The cells were harvested and lysed 2 days posttransfection. The lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-VP antibody and reprobed with anti-β-actin. The lysates were also analyzed by Western blotting using anti-NP1 and anti-HA (for mCherry) antibodies. (C) Northern blot analysis of VP mRNAs. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. The cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted 2 days posttransfection. The total-RNA samples were analyzed by Northern blotting using the NSCap probe. EB-stained 18S rRNA bands are shown. Detected bands of VP mRNA and (pA)p mRNA are indicated. The asterisk denotes various NS-encoding mRNAs. Lane M, RNA ladder marker. (D) Quantification of VP mRNAs on a Northern blot. The bands of VP mRNA and (pA)p mRNA in each lane of panel C were quantified and normalized to the level of 18S rRNA. The intensity of the VP mRNA band in lane 4 was arbitrarily set as 100%. Relative intensities were calculated for the bands in the other lanes. Means and standard deviations were calculated from the results of three independent experiments. The P values shown were calculated using a two-tailed Student t test. **, P < 0.01. (E) Determination of the usage of the A1, D2, and A3 splice sites using RPA. Ten micrograms of total RNA isolated 2 days posttransfection from HEK 293 cells transfected with plasmids as indicated was protected by the pA1D2 and pA3 probes or by their homology counterparts, as indicated. Lane M, 32P-labeled RNA markers (22), with sizes indicated on the left. The origins of the protected bands are shown with sizes. Spl, spliced RNAs; Unspl, unspliced RNAs.

As controls, NP1 did not alter the splicing of introns 1 and 2 of the mRNAs generated from pCMVNS*(In3Δ)Cap (Fig. 8E, lanes 1 and 4) or splicing of the heterogeneous introns (Epo introns 1 and 4) of the mRNAs generated from pCMVEpoIn14(In3Δ)Cap (Fig. 8E, lanes 2 and 5). It also did not alter splicing of the three heterogeneous Epo introns (Epo introns 1, 2, and 4) of the mRNAs generated from pCMVEpoIn124Cap (Fig. 8E, lanes 3 versus 6, and 7 versus 8).

Thus, these results strongly suggested that the role of NP1 in increasing the read-through of the (pA)p site (the level of VP mRNA) is independent of splicing at the A3 splice acceptor and the intervening intron sequence. Since both the pCMVEpoIn14(In3Δ)Cap and pCMVEpoIn124Cap constructs did not contain any NS ORFs, the function of NP1 in facilitating the VP mRNA to read through the (pA)p site is also independent of NS1 to -4.

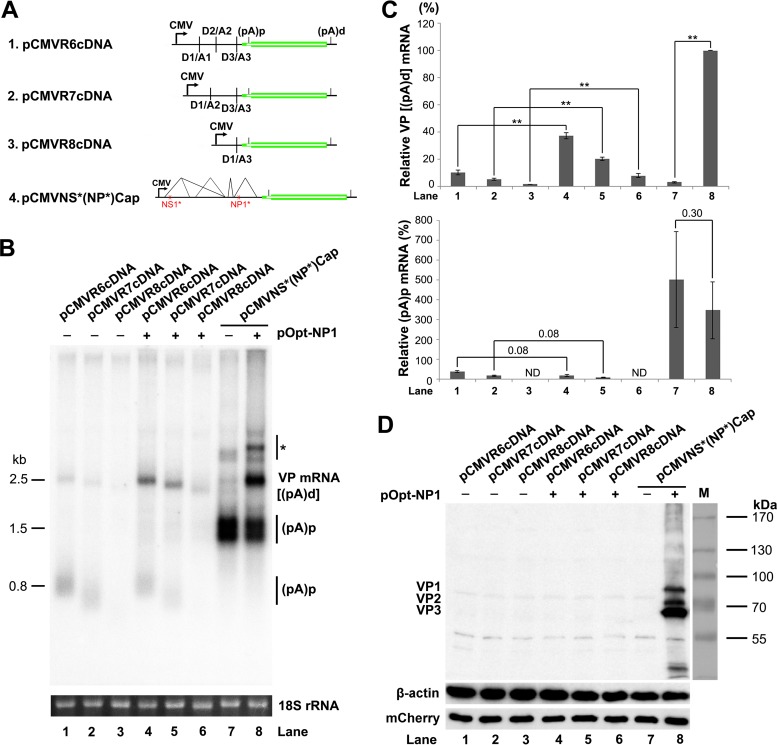

Furthermore, we evaluated the impact of NP1 on the expression of VP mRNA from various VP cDNA constructs. NP1 enhanced VP mRNA expression from all the VP cDNA constructs (Fig. 9B, lanes 4 to 6 versus 1 to 3). With NP1 provided in trans, the level of VP mRNA was increased by 3.7-, 4-, and 6-fold from the expression of R6, R7, and R8 VP cDNA constructs, respectively (Fig. 9B and C, lanes 1 versus 4, 2 versus 5, and 3 versus 6). Again, as a control, with NP1 provided in trans, the NS1 and NP1 knockout construct pCMVNS*(NP*)Cap expressed VP mRNA (at ∼2.5 kb [Fig. 1A, R6]) at a level over 30 times greater than that without NP1, whereas the level of (pA)p mRNA (at ∼1.5 kb [Fig. 1A, R5s]) did not significantly change (Fig. 9B and C, lanes 7 versus 8). However, the increased VP mRNAs from the cDNA constructs by NP1 were still not sufficient to express capsid proteins (Fig. 9D, lanes 4 to 6). Of note, with NP1 provided in trans, the level of (pA)p mRNA (at ∼0.8 kb) generated from the cDNA constructs was not significantly changed [Fig. 9C, (pA)p mRNA]. These results suggested that the increased read-through of VP mRNA is not due to the simple conversion of the (pA)p mRNA to (pA)d (VP) mRNA.

FIG 9.

NP1 increased VP mRNA production from cDNA constructs. (A) Diagrams of HBoV1 cDNA constructs, along with the pCMVNS*(NP*)Cap control. (B) Northern blot analysis of VP and (pA)p mRNAs. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids, as indicated, with (+) or without (−) cotransfection of pOpt-NP1. The cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted 2 days posttransfection. The RNA samples were analyzed by Northern blotting using the NSCap probe. EB-stained 18S rRNA bands of each sample are shown. The identities of detected bands are indicated. The asterisk denotes various NS-encoding mRNAs. (C) Quantification of VP and (pA)p mRNAs on a Northern blot. The bands of VP mRNA and (pA)p mRNA in each lane of panel B were quantified and normalized to the level of 18S rRNA. The intensity of the VP mRNA band in lane 8 was arbitrarily set as 100%. Relative intensities were calculated for the bands in the other lanes. Means and standard deviations were calculated from three independent experiments. The P values shown were calculated using a two-tailed Student t test. **, P < 0.01. ND, not detectable. (D) Western blot analysis of capsid proteins. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. The cells were harvested and lysed 2 days posttransfection. The lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-VP antibody. The blot was reprobed using an anti-β-actin antibody. The lysates were also analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-HA antibody for mCherry expression.

Taken together, these results confirmed that the NP1 protein facilitates VP mRNA read-through of the (pA)p site independently of any splicing events.

Knockout of the internal polyadenylation signals in the center of the viral genome compensates for the requirement for NP1 protein in the expression of capsid proteins.

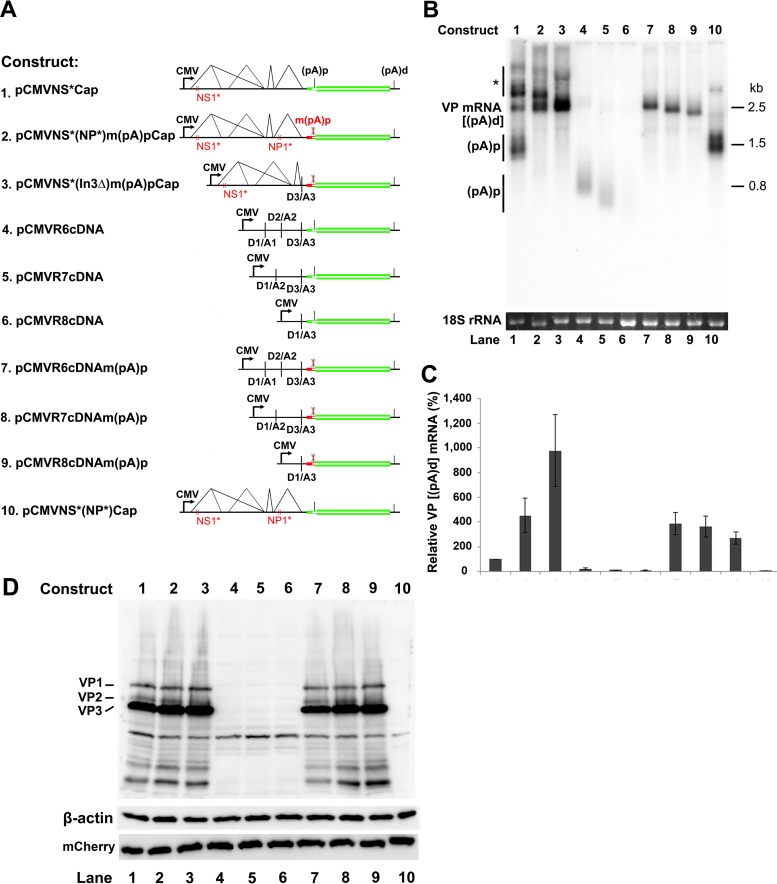

We next examined the role of the (pA)p site in blocking the read-through of VP mRNA and capsid protein expression. First, we made mutations of the PAS AAUAAA site at nt 3485 (16), as well as mutations of its upstream and downstream regions, which often regulate polyadenylation (24, 25), in pCMVNS*Cap. We failed to decrease the level of (pA)p mRNA or increase the level of VP mRNA (data not shown). Since there are a series of five PASs in the VP1 start-VP3 start-encoding region, we made silent mutations of the entire VP1 start-VP3 start-encoding sequences [m(pA)p], which cover all five PASs (Fig. 2). We observed that the constructs that bore the m(pA)p mutation no longer generated (pA)p mRNA (Fig. 10B and C, (pA)p, lanes 2, 3, and 7 to 9) but produced much higher levels of VP mRNA (Fig. 10B and C, VP mRNA, lanes 2, 3, and 7 to 9). In agreement with this finding, the m(pA)p mutation enabled capsid protein expression in the absence of NP1 from the NSCap gene constructs (Fig. 10D, lanes 2 and 3 versus 10), as well as the VP cDNA constructs (Fig. 10D, lanes 7 to 9 versus 4 to 6).

FIG 10.

Mutation of the (pA)p site enables VP mRNA production and capsid protein expression in the absence of NP1. (A) HBoV1 NSCap and cDNA constructs. HBoV1 NS and Cap genes and cDNA constructs are diagrammed, along with the pCMVNS*(NP*)Cap control. (B) Northern blot analysis of VP and (pA)p mRNAs. HEK 293 cells were transfected with constructs as indicated. The total-RNA samples were analyzed by Northern blotting using the NSCap probe. EB-stained 18S rRNA bands are shown. Detected bands of VP and (pA)p mRNAs are indicated on the left of the blot. The asterisk denotes various NS-encoding mRNAs. (C) Quantification of VP and (pA)p mRNAs on a Northern blot. The bands of VP and (pA)p mRNAs in each lane in panel B were quantified and normalized to 18S rRNA. The intensity of the VP mRNA band in lane 1 was arbitrarily set as 100%. Relative intensities were calculated for the bands of both VP and (pA)p mRNAs in the other lanes. Means and standard deviations were calculated from the results of three independent experiments. (D) Western blot analysis of capsid proteins. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. The cell lysates of each transfection were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-VP antibody. The blot was reprobed with an anti-β-actin antibody. The lysates were also analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-HA antibody for mCherry expression.

Thus, our results confirmed that internal polyadenylation prevents HBoV1 pre-mRNA from transcribing through the (pA)p site, which controls the production of VP mRNA and therefore also prevents the expression of capsid proteins. Of note, VP mRNA expressed from the NSCap constructs migrated at the same position as the mRNA expressed from the R6 cDNA (Fig. 10B, lanes 1 to 3 versus 7), suggesting that R6 mRNA is the VP mRNA.

DISCUSSION

The NP1 protein is a unique small nonstructural protein expressed only by members of the genus Bocaparvovirus among parvoviruses (16, 18, 26, 27). It is required for efficient replication of Bocaparvovirus DNA (13, 18). The NP1 protein shares features among members of the genus Bocaparvovirus. Both the BPV1 and HBoV1 NP1 proteins can complement the loss of NP1 during MVC DNA replication to some extent (18). The HBoV1 NP1 protein could complement some functions of the minute virus of mice (MVM) NS2 protein during an early phase of infection (28).

In a previous study, we showed that MVC NP1 plays a role in regulating capsid protein expression by facilitating the VP-encoding mRNA transcript read-through of the internal polyadenylation site (29). However, in that study, we did not differentiate the function of NP1 in enhancing splicing of VP-encoding mRNA transcripts at the A3 splice acceptor from its function in solely facilitating the (pA)p read-through of VP-encoding mRNA transcripts (29), since all VP-encoding mRNA transcripts must be spliced at the A3 splice acceptor (12, 16, 18). In the present study, we demonstrated that HBoV1 NP1 plays dual roles in controlling the production of VP mRNA. First, HBoV1 NP1 is critical to the splicing of the VP mRNA at the A3 splice acceptor, which is essential to generate VP mRNA. Second, HBoV1 NP1 facilitates viral pre-mRNA read-through of the internal (pA)p site for the production of VP mRNA, independently of any splicing events. More importantly, the function of HBoV1 NP1 in capsid protein expression is independent of the other four nonstructural proteins (NS1 to -4).

We observed that when splicing was involved (from the constructs that contain introns), NP1 increased VP mRNA to a much higher level on average than in the absence of splicing (from these cDNA constructs) (Fig. 8 versus 9). This finding suggests that splicing boosts NP1-facilitated read-through of the (pA)p site. Of note, while NP1 increases the read-through transcript of VP mRNA, (pA)p mRNA does not decrease significantly in most cases, suggesting that the increased read-through of VP-encoding mRNA transcripts (VP mRNA) is not merely a conversion of the (pA)p mRNA but is likely an activation of transcription. Moreover, replacing the D3-A3 intron with heterogeneous Epo intron 4 destroyed the NP1 protein dependence on the splicing at the A3 splice acceptor (Fig. 8), suggesting that the role of HBoV1 NP1 in enhancing splicing of VP mRNA at the A3 splice site is dependent on the intervening sequence of the D3-A3 intron. Since HBoV1 NP1 has a repeated RS (arginine/serine) motif at the N terminus, we speculate that HBoV1 NP1 may function as an SR protein to directly interact with the intervening intron sequence as the MVC NP1 does (30). On the other hand, during cellular mRNA processing, RNA transcription, splicing, and polyadenylation are all coupled (31). As VP mRNA must be spliced at the A3 splice site and read through the (pA)p site, we speculate that NP1 may target the transcription complex, which initiates at the P5 promoter to activate transcription, enhances splicing at the A3 splice site, and prevents internal polyadenylation. Therefore, HBoV1 NP1 is the first example of a parvovirus nonstructural protein that has multiple functions in viral pre-mRNA processing. Since NP1 is required for replication of HBoV1 infectious DNA (13), we are not able to prove the critical functions of NP1 in viral pre-mRNA processing when the transcription template, HBoV1 replicative DNA, is replicating. Dissecting the functions of NP1 in viral pre-mRNA processing from viral DNA replication will be attempted in the future.

We noticed that the level of the VP mRNA is not proportionally related to the level of capsid proteins (Fig. 8 and 10). We are currently studying this discrepancy. One interpretation could be that a minimal level of VP mRNA is required for the translation of capsid proteins. However, in the cases of highly expressed VP mRNA from these (pA)p knockout constructs (Fig. 10), the higher level of VP mRNA did not express more capsid proteins. We speculate that NP1 may play a role in the translation of VP mRNA. Without NP1 expression from the (pA)p knockout constructs, a higher level of VP1 mRNA is required to efficiently translate capsid proteins. Further investigation into the multiple functions of NP1 is warranted.

In this study, we confirmed expression of the novel VP2 from a noncanonical translation initiation site (GUG) ORF. Importantly, we identified simple HBoV1 VP ORF constructs [pCMVR6-8cDNAm(pA)p] that do not express any of the NS proteins (NS1 to -4 and NP1) but express HBoV1 capsid proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3 at a level and at a ratio (VP1 versus VP2 versus VP3) similar to that of the packaging helper plasmid pHBoV1NSCap that has been used for rAAV2/HBoV1 vector production (19). Thus, in the future, we will use the HBoV1 Cap gene cDNAm(pA)p constructs to optimize rAAV2/HBoV1 vector production in HEK 293 cells without interference from any HBoV1 NS proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Qiu laboratory for discussions and critical readings of the manuscript.

The study was supported by PHS grants AI105543 and AI112803 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and a subaward of P30 GM103326 from the Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) Program of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health, to Jianming Qiu and by award YAN15XX0 from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation to Ziying Yan.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Andersson B. 2005. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:12891–12896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotmore SF, Agbandje-McKenna M, Chiorini JA, Mukha DV, Pintel DJ, Qiu J, Soderlund-Venermo M, Tattersall P, Tijssen P, Gatherer D, Davison AJ. 2014. The family Parvoviridae. Arch Virol 159:1239–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1914-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson FB, Qiu J. 2011. Bocavirus, Parvoviridae, Parvovirinae, p 1209–1215. In Tidona C, Darai G (ed), The Springer index of viruses, 2nd ed Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allander T, Jartti T, Gupta S, Niesters HG, Lehtinen P, Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Waris M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, van den Hoogen BG, Hyypia T, Ruuskanen O. 2007. Human bocavirus and acute wheezing in children. Clin Infect Dis 44:904–910. doi: 10.1086/512196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin F, Zeng A, Yang N, Lin H, Yang E, Wang S, Pintel D, Qiu J. 2007. Quantification of human bocavirus in lower respiratory tract infections in China. Infect Agent Cancer 2:3. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen A, Nordbo SA, Krokstad S, Rognlien AG, Dollner H. 2010. Human bocavirus in children: mono-detection, high viral load and viraemia are associated with respiratory tract infection. J Clin Virol 49:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng Y, Gu X, Zhao X, Luo J, Luo Z, Wang L, Fu Z, Yang X, Liu E. 2012. High viral load of human bocavirus correlates with duration of wheezing in children with severe lower respiratory tract infection. PLoS ONE 7:e34353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Don M, Soderlund-Venermo M, Valent F, Lahtinen A, Hedman L, Canciani M, Hedman K, Korppi M. 2010. Serologically verified human bocavirus pneumonia in children. Pediatr Pulmonol 45:120–126. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edner N, Castillo-Rodas P, Falk L, Hedman K, Soderlund-Venermo M, Allander T. 2012. Life-threatening respiratory tract disease with human bocavirus-1 infection in a four-year-old child. J Clin Microbiol 50:531–532. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05706-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantola K, Hedman L, Allander T, Jartti T, Lehtinen P, Ruuskanen O, Hedman K, Soderlund-Venermo M. 2008. Serodiagnosis of human bocavirus infection. Clin Infect Dis 46:540–546. doi: 10.1086/526532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin ET, Kuypers J, McRoberts JP, Englund JA, Zerr DM. 2015. Human bocavirus-1 primary infection and shedding in infants. J Infect Dis 212:516–524. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dijkman R, Koekkoek SM, Molenkamp R, Schildgen O, van der Hoek L. 2009. Human bocavirus can be cultured in differentiated human airway epithelial cells. J Virol 83:7739–7748. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00614-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Q, Deng X, Yan Z, Cheng F, Luo Y, Shen W, Lei-Butters DC, Chen AY, Li Y, Tang L, Soderlund-Venermo M, Engelhardt JF, Qiu J. 2012. Establishment of a reverse genetics system for studying human bocavirus in human airway epithelia. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002899. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng X, Yan Z, Luo Y, Xu J, Cheng Y, Li Y, Engelhardt J, Qiu J. 2013. In vitro modeling of human bocavirus 1 infection of polarized primary human airway epithelia. J Virol 87:4097–4102. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03132-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng X, Li Y, Qiu J. 2014. Human bocavirus 1 infects commercially available primary human airway epithelium cultures productively. J Virol Methods 195:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen AY, Cheng F, Lou S, Luo Y, Liu Z, Delwart E, Pintel D, Qiu J. 2010. Characterization of the gene expression profile of human bocavirus. Virology 403:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen W, Deng X, Zou W, Cheng F, Engelhardt JF, Yan Z, Qiu J. 2015. Identification and functional analysis of novel non-structural proteins of human bocavirus 1. J Virol 89:10097–10109. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01374-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Y, Chen AY, Cheng F, Guan W, Johnson FB, Qiu J. 2009. Molecular characterization of infectious clones of the minute virus of canines reveals unique features of bocaviruses. J Virol 83:3956–3967. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02569-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan Z, Keiser NW, Song Y, Deng X, Cheng F, Qiu J, Engelhardt JF. 2013. A novel chimeric adenoassociated virus 2/human bocavirus 1 parvovirus vector efficiently transduces human airway epithelia. Mol Ther 21:2181–2194. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan Z, Zhang Y, Duan D, Engelhardt JF. 2000. Trans-splicing vectors expand the utility of adeno-associated virus for gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6716–6721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen AY, Kleiboeker S, Qiu J. 2011. Productive parvovirus B19 infection of primary human erythroid progenitor cells at hypoxia is regulated by STAT5A and MEK signaling but not HIF alpha. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002088. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu J, Nayak R, Tullis GE, Pintel DJ. 2002. Characterization of the transcription profile of adeno-associated virus type 5 reveals a number of unique features compared to previously characterized adeno-associated viruses. J Virol 76:12435–12447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12435-12447.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cecchini S, Negrete A, Virag T, Graham BS, Cohen JI, Kotin RM. 2009. Evidence of prior exposure to human bocavirus as determined by a retrospective serological study of 404 serum samples from adults in the United States. Clin Vaccine Immunol 16:597–604. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00470-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zarudnaya MI, Kolomiets IM, Potyahaylo AL, Hovorun DM. 2003. Downstream elements of mammalian pre-mRNA polyadenylation signals: primary, secondary and higher-order structures. Nucleic Acids Res 31:1375–1386. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Q, Deng X, Best SM, Bloom ME, Li Y, Qiu J. 2012. Internal polyadenylation of parvoviral precursor mRNA limits progeny virus production. Virology 426:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lederman M, Patton JT, Stout ER, Bates RC. 1984. Virally coded noncapsid protein associated with bovine parvovirus infection. J Virol 49:315–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiu J, Cheng F, Johnson FB, Pintel D. 2007. The transcription profile of the bocavirus bovine parvovirus is unlike those of previously characterized parvoviruses. J Virol 81:12080–12085. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00815-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mihaylov IS, Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. 2014. Complementation for an essential ancillary non-structural protein function across parvovirus genera. Virology 468–470:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sukhu L, Fasina O, Burger L, Rai A, Qiu J, Pintel DJ. 2013. Characterization of the non-structural proteins of the bocavirus minute virus of canine (MVC). J Virol 87:1098–1104. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02627-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fasina OO, Dong Y, Pintel DJ. 2015. NP1 protein of the bocaparvovirus minute virus of canines controls access to the viral capsid genes via its role in RNA processing. J Virol 90:1718–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bentley DL. 2014. Coupling mRNA processing with transcription in time and space. Nat Rev Genet 15:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nrg3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]