ABSTRACT

Genotype 3 (gt3) hepatitis E virus (HEV) infections are emerging in Western countries. Immunosuppressed patients are at risk of chronic HEV infection and progressive liver damage, but no adequate model system currently mimics this disease course. Here we explore the possibilities of in vivo HEV studies in a human liver chimeric mouse model (uPA+/+Nod-SCID-IL2Rγ−/−) next to the A549 cell culture system, using HEV RNA-positive EDTA-plasma, feces, or liver biopsy specimens from 8 immunocompromised patients with chronic gt3 HEV. HEV from feces- or liver-derived inocula showed clear virus propagation within 2 weeks after inoculation onto A549 cells, compared to slow or no HEV propagation of HEV RNA-positive, EDTA-plasma samples. These in vitro HEV infectivity differences were mirrored in human-liver chimeric mice after intravenous (i.v.) inoculation of selected samples. HEV RNA levels of up to 8 log IU HEV RNA/gram were consistently present in 100% of chimeric mouse livers from week 2 to week 14 after inoculation with human feces- or liver-derived HEV. Feces and bile of infected mice contained moderate to large amounts of HEV RNA, while HEV viremia was low and inconsistently detected. Mouse-passaged HEV could subsequently be propagated for up to 100 days in vitro. In contrast, cell culture-derived or seronegative EDTA-plasma-derived HEV was not infectious in inoculated animals. In conclusion, the infectivity of feces-derived human HEV is higher than that of EDTA-plasma-derived HEV both in vitro and in vivo. Persistent HEV gt3 infections in chimeric mice show preferential viral shedding toward mouse bile and feces, paralleling the course of infection in humans.

IMPORTANCE Hepatitis E virus (HEV) genotype 3 infections are emerging in Western countries and are of great concern for immunosuppressed patients at risk for developing chronic HEV infection. Lack of adequate model systems for chronic HEV infection hampers studies on HEV infectivity and transmission and antiviral drugs. We compared the in vivo infectivity of clinical samples from chronic HEV patients in human liver chimeric mice to an in vitro virus culture system. Efficient in vivo HEV infection is observed after inoculation with feces- and liver-derived HEV but not with HEV RNA-containing plasma or cell culture supernatant. HEV in chimeric mice is preferentially shed toward bile and feces, mimicking the HEV infection course in humans. The observed in vivo infectivity differences may be relevant for the epidemiology of HEV in humans. This novel small-animal model therefore offers new avenues to unravel HEV's pathobiology.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is a nonenveloped positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus of the genus Orthohepevirus and family Hepeviridae (1). Four major HEV genotypes infecting humans have been described so far. Genotype 1 (gt1) and gt2 strains are isolated only from humans, whereas gt3 and gt4 strains are considered zoonotic viruses, present in both humans and several other species like pigs and wild game. HEV is spread through the oral-fecal route via contaminated water in developing countries or, among other routes, via direct contact with animals or the consumption of undercooked meat in industrialized countries. In immunocompetent individuals, HEV infection is mainly self-limiting and often asymptomatic and thus remains largely underdiagnosed. HEV infections in immunosuppressed patients, such as solid-organ transplant recipients, often persist and can progress quickly to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis (2–4).

HEV gt3 infections are emerging in Western countries, including France, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands (5–7). Despite an overall decrease in anti-HEV seroprevalence from 1996 to 2011, young adult blood donors demonstrated higher seroprevalences from 2000 to 2011 (8, 9). In addition, HEV RNA-positive blood donations were reported to increase in the Netherlands since 2012 (10). Although the exact source of this HEV gt3 infection is unknown, it is likely that domestic swine and pig farming plays a critical role. HEV RNA gt3 was detected in approximately one-half of the pig farms in the Netherlands (11).

Human liver chimeric mice have contributed significantly to our understanding of viral pathobiology, virus-host interactions, and antiviral therapy for hepatitis B, C, and D infections (12–18). Since no animal model for chronic HEV infection is available, we examined the infectivity of HEV gt3 samples of different clinical origins in the humanized liver urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) transgenic mouse model on a severely immunodeficient NOD/Shi-scid/IL-2Rγnull background (uPA-NOG) and compared this to the established adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial cells (A549) culture system (19–22). We demonstrate that in vitro infectivity differences of feces-, liver-, and plasma-derived HEV are paralleled in vivo. These differences are most apparent when inocula from a single patient are used with a similar HEV RNA content. Once infected, persistent intrahepatic viral replication is seen in all chimeric mice, with preferential viral shedding to mouse bile and feces, reminiscent of human HEV infections. Human liver chimeric mice are therefore a suitable model for future studies on HEV transmission and pathobiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inoculum preparation.

Inocula were obtained from heart (n = 4), liver (n = 1), and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (n = 2) transplant recipients and one recipient who received both heart and kidney grafts (Table 1), treated either at the University Hospital Antwerp or at the Erasmus Medical Center (21, 22). Clinical sequelae have been described elsewhere (4, 21, 22). All had detectable HEV RNA in their EDTA-plasma for more than 6 months (defined as chronic HEV infection). Table 1 shows the results of the anti-HEV IgM and IgG antibody determination in the EDTA-plasma inocula obtained with a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Wantai, Beijing, China). Open reading frame 1 (ORF1) and ORF2 sequences of the inocula are available from GenBank (Table 1). Fecal suspensions were prepared as follows: 3 g feces was vortexed thoroughly in 10 ml saline and centrifuged (450 × g, 3 min). After 2 additional centrifugation steps (14,000 × g, 5 min), the supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm filter. Cryopreserved liver biopsy specimen fragments from one heart transplant patient and from one allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patient were homogenized in 500 μl saline using ceramic beads. The supernatant was used as inoculum after centrifugation (5,000 × g, 10 min). All inocula were kept at −80°C until use.

TABLE 1.

Inocula of chronic HEV gt3 patients for in vitro and in vivo infection

| Case ID | 1st yr of patient's HEV positivity | Age at HEV+ diagnosis | Sex | Morbidityb | GenBank accession no. |

Plasma serostatusc (IgM/IgG) | HEV RNA (log IU/ml) |

Reference(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1 | ORF2 | Plasma | Fecesd | Liver | |||||||

| HEV0008 | 2008 | 55 | F | Allo-HSCT | JQ015407 | KT198654 | +/+ | 6.18 | 6.09 | 5.31 | 21 |

| HEV0014a | 2011 | 40 | F | Allo-HSCT | KC171436 | KP895853 | −/− | 5.46/6.84a | 5.61 | − | 21 |

| HEV0033 | 2010 | 51 | M | HTx | JQ015427 | KT198656 | +/+ | 5.73 | 6.20 | − | 4, 22 |

| HEV0047 | 2010 | 56 | M | HTx | JQ015425 | KT198657 | −/+ | 6.72 | 6.69 | − | 4, 22 |

| HEV0063 | 2010 | 19 | M | LTX | JQ015426 | KT198658 | +/+ | 4.96 | 5.18 | − | 4, 22 |

| HEV0069a | 2010 | 62 | M | HTx | JQ015423 | KP895854 | −/− | 6,23 | 6.37/8.80a | − | 4, 22 |

| HEV0081 | 2009 | 50 | M | HTx + KTx | JQ015418 | KT198659 | +/+ | 4.91 | 5.15 | − | 4, 22 |

| HEV0122a | 2014 | 63 | M | HTX | KP895856 | KP895855 | −/− | 5.83/6.74a | 6.12/8.80a | 4.87/6.26a | This publication |

Undiluted inocula used for in vivo infection.

Allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; HTx, heart transplantation; LTx, liver transplantation; KTx, kidney transplantation.

As determined by anti-HEV IgM and anti-HEV IgG ELISA (Wantai, Beijing, China).

Feces inocula were diluted to the plasma HEV RNA level in order to use an identical HEV RNA level for infection of the A549 cells.

Hepatitis E virus propagation.

A549 cells were seeded on a coverslip in a 24-well plate in A549 growth medium containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Lonza) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Greiner Bio-one, Kremsmünster, Austria), 0.08% NaHCO3, 2 mM l-glutamine (Lonza), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (pen-strep; Lonza), and 0.5 μg/μl amphotericin B (Pharmacy, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands). Three days after seeding, cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) and then were either inoculated with HEV derived from different sample types or mock inoculated and incubated for 1 h at 36.5°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Liver-derived samples were diluted 1:10 prior to inoculation to dilute toxic substances. The virus suspension was then removed, and cells were washed three times with PBS before adding maintenance medium, containing a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham's F-12 (Life technologies), supplemented with 2% FBS, 20 mM HEPES (Lonza), 0.4% NaHCO3, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.3% bovine serum albumin fraction V (BSA; Lonza), 1% pen-strep, and 2.5 μg/μl amphotericin B, and incubated at 36.5°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Proper washing was documented by the absence of HEV RNA (cycle threshold [CT], >38) in the last PBS supernatant. For monitoring virus propagation, every 2 to 3 days cells were inspected for cytopathogenic effect (CPE) and viability, culture medium was refreshed with maintenance medium (1:1), and supernatant was taken for HEV quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR).

Mouse origin and genotyping.

uPA-NOG mice were kindly provided by the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Kawasaki, Japan) (19). Mice were bred at the Central Animal Facility of the Erasmus Medical Center. Offspring zygosity was identified using a copy number duplex qPCR performed on phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)-extracted genomic mouse DNA from toe snip. The TaqMan Genotyping master mix (Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with the TaqMan uPA genotyping assay (Mm00422051_cn; Life Technologies) and Tert gene references mix (Life technologies) were used according to the manufacturer's protocol. All animal work was conducted according to relevant Dutch national guidelines. The study protocol was approved by the animal ethics committee of the Erasmus Medical Center (DEC nr 141-12-11).

Human hepatocyte transplantation.

uPA homozygous mice, 6 to 12 weeks of age, were transplanted as previously described (12). In short, mice were anesthetized and transplanted via intrasplenic injection with 0.5 × 106 to 2 × 106 viable commercially available cryopreserved human hepatocytes (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland, and Corning, Corning, NY, USA). Graft take was determined by human albumin in mouse serum using an ELISA with human albumin cross-adsorbed antibody (Bethyl laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA) as previously described (12).

Mouse infection.

Mice were inoculated intravenously (i.v.) with 135 to 200 μl pooled patient EDTA-plasma (6.8 log IU/ml), individual patient EDTA-plasma (6.7 log IU/ml), a homogenized liver biopsy specimen fragment (6.3 log IU/ml), feces (8.8 log IU/ml or diluted to 6.8 log IU/ml), or 7th passage (P7) culture supernatant initially derived from feces (7.4 log IU/ml) containing HEV gt3 (Table 1 and Fig. 1J). The use of patient material was approved by the medical ethical committees of Erasmus MC and Antwerp University Hospital.

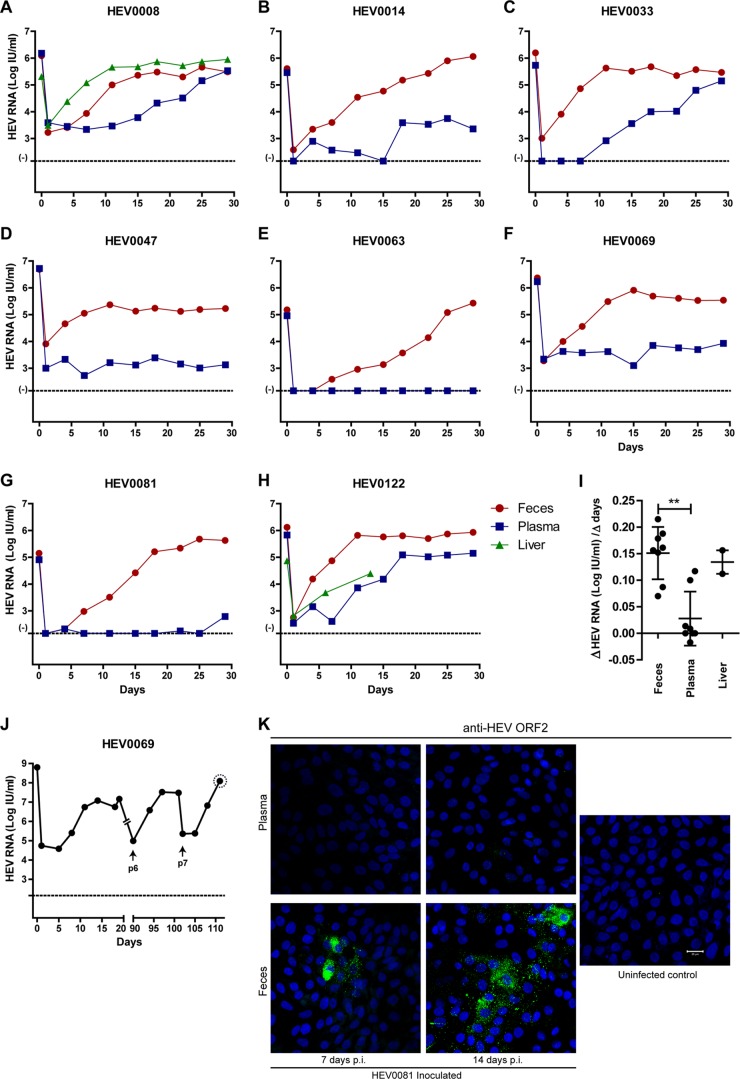

FIG 1.

Differences in in vitro infectivity of HEV gt3-containing clinical samples on A549 cells. Gradual increase in HEV RNA levels in supernatant of A549 cells after inoculation of feces-derived (A to H) or liver-derived (A, H) HEV (red and green lines, respectively). No or slower increase in HEV RNA levels in supernatants of A549 cells after inoculation of EDTA-plasma-derived HEV (A to H, blue line). (I) Log HEV RNA increase per day within the first 2 weeks after inoculation with feces-, plasma-, and liver-derived HEV as depicted in panels A to H. (J) Increasing HEV RNA titers after prolonged culture. Arrows indicate the first measurement after passage. The dotted circle around the last P7 viral load indicates the inoculum used for in vivo challenge described in the legend to Fig. 3A. (K) HEV ORF2 immunofluorescence of HEV-infected A549 cells 7 and 14 days after inoculation of HEV0081 feces- and plasma-derived virus and of uninfected control A549 cells. Bar, 20 μM HEV RNA was quantified with qRT-PCR, and CT values of >38 are considered background (−) (A to H and J). The HEV RNA concentrations of the initial inocula are indicated on time point 0 (A to H and J). Error bars indicate means ± SD; **, P < 0.01 (I).

Histology, immunohistochemistry, and HEV ORF2 immunofluorescence.

Mouse livers were fixed in 4% formaldehyde solution (Merck-Millipore). Standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed, and human hepatocytes were identified using goat anti-human albumin cross-adsorbed antibody (Bethyl laboratories) or mouse anti-human mitochondria antibody (Merck). To visualize the detected antigens, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark) was added as a substrate, and slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. To confirm in vitro HEV replication after 7 to 14 days postinfection, cells were fixed in 80% acetone (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min, washed 3 times with PBS, and air dried. Cells were then blocked for 30 min at 36.5°C with 10% normal goat serum (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA), followed by washing three times in PBS. Subsequently, cells were stained for 1 h at 36.5°C with a 1:200 0.5% BSA–PBS diluted mouse-α-HEV ORF2 amino acids 434 to 547 antibody (MAB8002; Merck-Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), followed by staining with 1:200 0.5% BSA–PBS diluted goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies) for 1 h at 37°C. After washing with PBS, cells were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and pictures were taken using a confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM700).

HEV RNA detection.

All samples were screened for the presence of HEV RNA by an ISO15189:2012-validated, internally controlled quantitative real-time RT-PCR, described previously (22). CT values above 38 were considered background. HEV RNAs detected in samples with CT values below 38 are indicated with their calculated values. Feces was pretreated with transport and recovery buffer (STAR buffer; Roche, Almere, Netherlands) and chloroform. Liver tissues were homogenized using ceramic beads in 500 μl RPMI (Lonza). Mouse serum, bile, and liver homogenate supernatants were diluted 10-fold before extraction due to limited sample volume or to dilute any impurities inhibiting the qPCR.

Statistics.

Graphpad Prism 5.01 was used for statistical analysis. Nonnormally distributed data were log transformed. Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). The Michaelis-Menten nonlinear test was used to determine goodness of fit, and the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Mann-Whitney test were used to calculate the P values. Significance was set at P values of <0.05.

RESULTS

Infectivity differences of HEV gt3 from patient plasma, feces, or liver on A549 cells in vitro.

Different clinical isolates from 8 chronic HEV gt3 patients were used to infect cultured A549 cells (Table 1). Feces samples were diluted in order to load identical HEV RNA amounts of plasma- and feces-derived inocula on the A549 cells. A549 cells were efficiently infected with HEV derived from feces and liver biopsy specimens with increasing HEV RNA titers in supernatant up to 5.05 log IU/ml within 7 days (Fig. 1A to H). HEV propagation was less efficient when using HEV RNA-positive EDTA-plasma specimens, with 4 (HEV0008, HEV0014, HEV0033, and HEV0122) of 8 samples showing increasing HEV RNA titers after 10 or 15 days postexposure regardless of their serostatus (Fig. 1A to H; Table 1). The different in vitro replication kinetics of feces- versus plasma-derived HEV is evident from the calculated slopes during the first 2 weeks after inoculation on A549 cells (Fig. 1I; mean slope, 0.151 versus 0.028 log HEV RNA IU per day, respectively, P < 0.01). HEV gt3 derived from patient HEV0069 feces was passaged seven times onto new cells, which resulted in increasing HEV RNA titers after each passage up to 8 log IU/ml (Fig. 1J). Anti-HEV ORF2 fluorescence staining confirmed HEV protein expression in feces-inoculated but not in plasma-inoculated A549 cells at day 7 and day 14 (Fig. 1K). HEV is visualized in the cytoplasm of clustered infected cells without obvious cytopathogenic effects. The percentage of infected cells was determined as 3 to 5% of total cells.

Successful infection of chimeric mice with feces-derived HEV gt3.

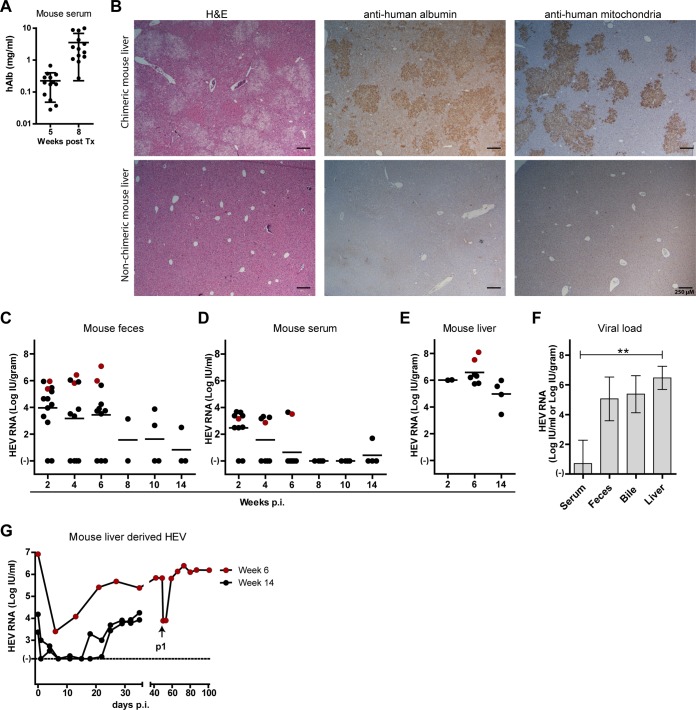

uPA-NOG mice successfully transplanted with human hepatocytes had increasing human albumin levels in serum (Fig. 2A), which correlated with liver repopulation by human hepatocytes as demonstrated by H&E, specific human albumin, and human mitochondrial staining (Fig. 2B) (12). To corroborate the observed feces-derived HEV in vitro infectivity, filtered undiluted fecal suspensions (see Materials and Methods) from patients HEV0069 and HEV0122 were i.v. inoculated into chimeric mice and the infection course was documented for 2, 6, or 14 weeks until mice were euthanized. During follow-up, HEV RNA was detected in feces of these mice with titers of up to 7 log IU/gram (3.1 ± 2.4 log IU HEV RNA/gram [Fig. 2C]), while HEV viremia was low and inconsistently detectable, with maximum viral loads of 3.6 log IU/ml (1.1 ± 1.5 log IU HEV RNA/ml [Fig. 2D]). All 13 inoculated animals had high intrahepatic HEV RNA titers at the time of euthanasia (6.0 ± 1.1 log IU HEV RNA/gram [Fig. 2E]). HEV is preferentially secreted via feces in infected individuals. In fact, HEV-seroconverted patients continue to shed HEV in feces for several weeks, even when HEV titers in serum drop to undetectable levels (3). We found that in infected animals the titers in serum were lower than the titers in feces, bile, and liver. In 5 infected mice at 6 weeks postinfection, the mean HEV RNA titers in serum, feces, bile, and liver were 0.7 ± 1.6 log IU/ml, 5.1 ± 1.5 log IU/gram, 5.4 ± 1.2 log IU/ml, and 6.5 ± 0.8 log IU/gram, respectively (P value 0.004, Kruskall-Wallis test [Fig. 2F]). These data suggest that virions are secreted preferentially through the biliary canaliculi, instead of basolaterally in the liver sinusoids. In addition, HEV0069 and HEV0122 isolates from mouse livers after 6 or 14 weeks of in vivo replication, respectively, could be propagated in vitro after exposure to A549 cells (Fig. 2G). The HEV0122 isolate was passaged further and could be maintained for over 3 months, reaching high HEV RNA levels (>6 log IU/ml) in the culture supernatant (Fig. 2G). Taken together, these data confirm the in vivo infectivity of feces-derived HEV gt3 with establishment of 100% persistent and productive HEV infections in chimeric mice.

FIG 2.

Persistent infection of human liver-chimeric mice with feces-derived HEV gt3 from two chronic HEV patients. (A) Human albumin levels were measured in mouse serum via ELISA to quantify the hepatocyte graft taken at 5 and 8 weeks posttransplantation (n = 13, geometric mean ± SD). (B) Liver histology of chimeric mouse livers at 8 weeks posttransplantation (upper panels) and nonchimeric mouse liver (lower panels); H&E (left panels), anti-human albumin (middle panels), and anti-human mitochondrial staining (right panels). (C to E) Chimeric mice (n = 13) were challenged i.v. with 8 log IU HEV RNA derived from human feces from patient HEV0069 (black dots) or patient HEV0122 (red dots) for 2, 6, or 14 weeks (n = 2, 7, and 4, respectively). HEV RNA levels were measured by qPCR in mouse feces (C), mouse serum (D), and mouse liver (E). (F) Comparison of HEV viral loads in serum, feces, bile, and liver at week 6 postinfection (n = 5, mean ± SD). (G) In vitro HEV propagation on A549 cells of mouse liver-derived HEV0122 (red dots) or HEV0069 (black dots) after in vivo replication for 6 or 14 weeks, respectively. The arrow indicates the first new data point after passage onto new A549 cells. **, P < 0.01.

Differences in in vitro HEV gt3 infectivity are reflected in vivo.

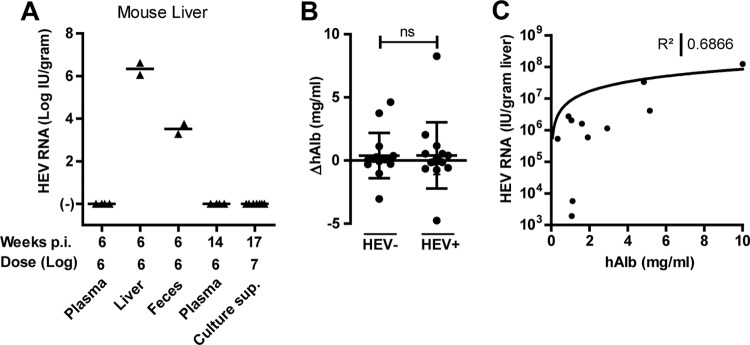

In order to assess the infectivity differences of HEV RNA-containing clinical samples, a total of 19 chimeric mice were challenged with EDTA-plasma samples from patients HEV0014 and HEV0122, with liver homogenate from patient HEV0122, with feces of patient HEV0069, or with a high-titer P7 culture supernatant of this patient's feces (Fig. 1J and 3A; Table 1). Care was taken to inject animals with similar HEV RNA-containing inocula, with some variation due to differences in injected volumes (135 to 200 μl). The respective inocula are indicated below the x axis (Fig. 3A). Given the need for liver HEV RNA quantification to demonstrate or rule out HEV infectivity, large liver fragments of sacrificed animals were collected at week 6 to week 17 after inoculation. Only liver- and feces-derived inocula proved to be infectious in chimeric mice. EDTA-plasma or A549 cell culture-derived inocula did not result in detectable HEV RNA levels at 6, 14, or 17 weeks after inoculation in any of the examined biological matrices (feces, sera, bile, and liver [Fig. 3A and data not shown]). In addition, untransplanted uPA+/−NOG mice inoculated with undiluted fecal suspensions from patient HEV0069 (8 log IU HEV RNA) remained HEV RNA negative in liver, serum, and feces, indicating that human hepatocytes are HEV target cells in vivo (n = 3; data not shown).

FIG 3.

Differences in in vivo infectivity of HEV gt3-containing clinical samples in human liver chimeric mice. Chimeric mice (n = 19) were challenged i.v. with HEV RNA-containing inocula derived from EDTA plasma (patients HEV0014 and HEV0122; n = 4, respectively), a cryopreserved liver biopsy specimen (patient HEV0122; n = 2), feces (patient HEV0069; n = 2), or P7 culture supernatant of patient HEV0069 feces (n = 7) (see Materials and Methods). The respective infectious doses are indicated below the x axis, as well as the duration of the infection in weeks. HEV RNA levels were measured by qPCR in mouse liver at euthanasia (A). (B) Changes in serum human albumin levels from HEV inoculation to the end of the follow-up for HEV RNA-negative and HEV RNA-positive mice (n = 23, P = 0.9339). (C) Nonlinear regression of chimerism, indicated by human albumin level in mouse serum (x axis), versus the HEV titer in the liver (y axis) at week 6 postinfection (n = 11).

The absence of detectable HEV RNA could not be ascribed to loss of chimerism, as the variation of human albumin levels during the course of the experiment was similar in HEV-positive and HEV-negative mice (Fig. 3B). Intrahepatic HEV RNA titers do vary and correlate with the degree of liver chimerism, as reflected by the human albumin levels in mouse serum (R2 = 0.6866) (Fig. 3C). However, the latter does not explain the infectivity differences observed between the different HEV-containing samples, as the animal with lowest human albumin values at the end of the follow-up (50 μg/ml) still had detectable intrahepatic HEV RNA levels. These data therefore corroborate a genuine biological difference in infectivity of HEV-containing samples of different origins.

DISCUSSION

Human HEV gt3 infections are emerging in Western countries, and immunosuppressed patients are at risk of developing chronic HEV with progressive liver fibrosis. In this study, we establish the human liver chimeric mouse as a model for chronic HEV gt3 infections and demonstrate intrinsic in vitro A549 cell culture and in vivo infectivity differences of HEV gt3-containing clinical samples. Our data show that human liver chimeric mice can develop a 100% chronic HEV infection, mimicking the infection course in solid-organ and bone marrow transplant recipients. HEV in these mice is preferentially shed in bile and feces, which corresponds to the secretion pattern seen in humans.

Feces- and liver-derived inocula led to rapid HEV RNA increases in the A549 cell culture system. The plateauing viral titers early after plasma inoculation may be ascribed to HEV cell surface detachment and gradual release into the supernatant, as HEV ORF2 staining remained negative after 7 days of culture (Fig. 1K). We observed intrinsic HEV infectivity differences that were most apparent when plasma, feces, and liver HEV isolates from the same patients (HEV0008 and HEV0122) were examined: plasma-derived HEV demonstrated slower or no replication in vitro and in vivo, respectively. HEV virions from plasma and feces have been found to differ in virion density, ascribed to a divergent lipid membrane content. In addition, culture-derived HEV has characteristics comparable to those of plasma-derived HEV (23, 24). Differences between these viruses might be caused by the detergent activity of bile acids, which could strip the HEV virions from their lipid membrane upon their passage toward the intestinal system (25). This different buoyant density may influence in vivo infectivity, as has previously been shown for the hepatitis C virus (18). Circulating inhibiting factors, including virus-specific antibodies, on the other hand, may also negatively influence the infectivity of the virus preparations. Nevertheless, we used only preseroconversion plasma samples in our in vivo infectivity assays.

Similar to 4 late resurgences of HEV RNA levels in vitro demonstrated here, others found productive in vitro infections with insertions in the ORF1 region after 5 to 6 weeks of culture of chronic HEV gt3 sera, but not of acute-phase sera (26–29).

The observation that human plasma-derived virus is less infectious in vivo may be relevant for the infectivity and epidemiology of HEV in humans. Indeed, only a limited number of cases of transfusion-transmitted HEV have been reported despite administration of contaminated blood products (3, 7, 30, 31). In addition, a recent retrospective survey of United Kingdom's plasma pool surprisingly showed that only one-half of HEV viremic British blood donors infected their recipients (7). The HEV transmission rate seemed to be dependent on the HEV RNA load and the status of anti-HEV antibodies in donor plasma. Ultimate proof of intrinsic infectivity differences of membranous or antibody-coated HEV particles will require delipidation and antibody depletion of plasma-derived inocula. While recent reports have shown HEV gt3 viremia among blood donors (10), Dutch national blood safety guidelines do not require nucleic acid testing (NAT) of the donor pool (32). This is of concern for solid-organ transplant patients, who are prone to developing chronic infections.

In conclusion, we have shown that feces- and liver-derived HEV gt3 induces a sustained infection in human liver chimeric mice with preferential viral shedding toward mouse bile and feces, mimicking the course of infection in humans. This novel small-animal model offers new avenues to study chronic HEV infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vincent Vaes from the Erasmus MC animal care facility for his assistance in performing biotechnical manipulations and Jolanda Voermans, Jolanda Maaskant, Kim Kreefft, Debby van Eck-Schipper, Marwa Karim, and Stalin Raj for excellent technical assistance.

We declare that we have no commercial relationships that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted manuscript.

Author's contributions: M.D.B.V.D.G., S.D.P., B.L.H., A.D.M.E.O., A.B., and T.V. designed the research; M.D.B.V.D.G., S.D.P., G.V.D.N., BLH, and T.V. performed the experiments; M.D.B.V.D.G., S.D.P., G.V.D.N., B.L.H., A.B., and T.V. conducted the analysis and interpretation of the data; M.D.B.V.D.G., S.D.P., and T.V. wrote the manuscript; S.D.P., B.L.H., A.D.M.E.O., T.V., and R.A.D.M. provided essential research tools; S.D.P., B.L.H., R.A.D.M., A.D.M.E.O., A.B., and T.V. performed critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Belgian Foundation Against Cancer (2014-087), an Erasmus MC fellowship 2011, the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI) (050-060-452), and the Virgo Consortium (FES0908).

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith DB, Simmonds P, International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses Hepeviridae Study Group, Jameel S, Emerson SU, Harrison TJ, Meng XJ, Okamoto H, Van der Poel WH, Purdy MA. 2014. Consensus proposals for classification of the family Hepeviridae. J Gen Virol 95:2223–2232. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.068429-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal R, Jameel S. 2011. Hepatitis E. Hepatology 54:2218–2226. doi: 10.1002/hep.24674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krain LJ, Nelson KE, Labrique AB. 2014. Host immune status and response to hepatitis E virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 27:139–165. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00062-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koning L, Pas SD, de Man RA, Balk AH, de Knegt RJ, ten Kate FJ, Osterhaus AD, van der Eijk AA. 2013. Clinical implications of chronic hepatitis E virus infection in heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant 32:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koot H, Hogema BM, Koot M, Molier M, Zaaijer HL. 2015. Frequent hepatitis E in the Netherlands without traveling or immunosuppression. J Clin Virol 62:38–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansuy JM, Saune K, Rech H, Abravanel F, Mengelle C, L Homme S, Destruel F, Kamar N, Izopet J. 2015. Seroprevalence in blood donors reveals widespread, multi-source exposure to hepatitis E virus, southern France, October 2011. Euro Surveill 20(119):pii:21127. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.19.21127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hewitt PE, Ijaz S, Brailsford SR, Brett R, Dicks S, Haywood B, Kennedy IT, Kitchen A, Patel P, Poh J, Russell K, Tettmar KI, Tossell J, Ushiro-Lumb I, Tedder RS. 2014. Hepatitis E virus in blood components: a prevalence and transmission study in southeast England. Lancet 384:1766–1773. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogema BM, Molier M, Slot E, Zaaijer HL. 2014. Past and present of hepatitis E in the Netherlands. Transfusion 54:3092–3096. doi: 10.1111/trf.12733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wenzel JJ, Sichler M, Schemmerer M, Behrens G, Leitzmann MF, Jilg W. 2014. Decline in hepatitis E virus antibody prevalence in southeastern Germany, 1996-2011. Hepatology 60:1180–1186. doi: 10.1002/hep.27244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaaijer HL. 2014. No artifact, hepatitis E is emerging. Hepatology doi: 10.1002/hep.27611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutjes SA, Lodder WJ, Lodder-Verschoor F, van den Berg HHJL, Vennema H, Duizer E, Koopmans M, Husman AMD. 2009. Sources of hepatitis E virus genotype 3 in the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 15:381–387. doi: 10.3201/eid1503.071472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanwolleghem T, Libbrecht L, Hansen BE, Desombere I, Roskams T, Meuleman P, Leroux-Roels G. 2010. Factors determining successful engraftment of hepatocytes and susceptibility to hepatitis B and C virus infection in uPA-SCID mice. J Hepatol 53:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanwolleghem T, Bukh J, Meuleman P, Desombere I, Meunier JC, Alter H, Purcell RH, Leroux-Roels G. 2008. Polyclonal immunoglobulins from a chronic hepatitis C virus patient protect human liver-chimeric mice from infection with a homologous hepatitis C virus strain. Hepatology 47:1846–1855. doi: 10.1002/hep.22244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanwolleghem T, Meuleman P, Libbrecht L, Roskams T, De Vos R, Leroux-Roels G. 2007. Ultra-rapid cardiotoxicity of the hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor BILN 2061 in the urokinase-type plasminogen activator mouse. Gastroenterology 133:1144–1155. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giersch K, Allweiss L, Volz T, Helbig M, Bierwolf J, Lohse AW, Pollok JM, Petersen J, Dandri M, Lutgehetmann M. 2015. Hepatitis delta co-infection in humanized mice leads to pronounced induction of innate immune responses in comparison to HBV mono-infection. J Hepatol 63:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bissig KD, Wieland SF, Tran P, Isogawa M, Le TT, Chisari FV, Verma IM. 2010. Human liver chimeric mice provide a model for hepatitis B and C virus infection and treatment. J Clin Invest 120:924–930. doi: 10.1172/JCI40094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucifora J, Xia Y, Reisinger F, Zhang K, Stadler D, Cheng X, Sprinzl MF, Koppensteiner H, Makowska Z, Volz T, Remouchamps C, Chou WM, Thasler WE, Huser N, Durantel D, Liang TJ, Munk C, Heim MH, Browning JL, Dejardin E, Dandri M, Schindler M, Heikenwalder M, Protzer U. 2014. Specific and nonhepatotoxic degradation of nuclear hepatitis B virus cccDNA. Science 343:1221–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1243462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindenbach BD, Meuleman P, Ploss A, Vanwolleghem T, Syder AJ, McKeating JA, Lanford RE, Feinstone SM, Major ME, Leroux-Roels G, Rice CM. 2006. Cell culture-grown hepatitis C virus is infectious in vivo and can be recultured in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:3805–3809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511218103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suemizu H, Hasegawa M, Kawai K, Taniguchi K, Monnai M, Wakui M, Suematsu M, Ito M, Peltz G, Nakamura M. 2008. Establishment of a humanized model of liver using NOD/Shi-scid IL2Rg(null) mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 377:248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka T, Takahashi M, Kusano E, Okamoto H. 2007. Development and evaluation of an efficient cell-culture system for hepatitis E virus. J Gen Virol 88:903–911. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82535-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Versluis J, Pas SD, Agteresch HJ, de Man RA, Maaskant J, Schipper ME, Osterhaus AD, Cornelissen JJ, van der Eijk AA. 2013. Hepatitis E virus: an underestimated opportunistic pathogen in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 122:1079–1086. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-492363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pas SD, de Man RA, Mulders C, Balk AH, van Hal PT, Weimar W, Koopmans MP, Osterhaus AD, van der Eijk AA. 2012. Hepatitis E virus infection among solid organ transplant recipients, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 18:869–872. doi: 10.3201/eid1805.111712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagashima S, Takahashi M, Jirintai S, Tanggis Kobayashi T, Nishizawa T, Okamoto H. 2014. The membrane on the surface of hepatitis E virus particles is derived from the intracellular membrane and contains trans-Golgi network protein 2. Arch Virol 159:979–991. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1912-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi M, Yamada K, Hoshino Y, Takahashi H, Ichiyama K, Tanaka T, Okamoto H. 2008. Monoclonal antibodies raised against the ORF3 protein of hepatitis E virus (HEV) can capture HEV particles in culture supernatant and serum but not those in feces. Arch Virol 153:1703–1713. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okamoto H. 2013. Culture systems for hepatitis E virus. J Gastroenterol 48:147–158. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0682-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johne R, Reetz J, Ulrich RG, Machnowska P, Sachsenroder J, Nickel P, Hofmann J. 2014. An ORF1-rearranged hepatitis E virus derived from a chronically infected patient efficiently replicates in cell culture. J Viral Hepat 21:447–456. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen HT, Torian U, Faulk K, Mather K, Engle RE, Thompson E, Bonkovsky HL, Emerson SU. 2012. A naturally occurring human/hepatitis E recombinant virus predominates in serum but not in faeces of a chronic hepatitis E patient and has a growth advantage in cell culture. J Gen Virol 93:526–530. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.037259-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shukla P, Nguyen HT, Faulk K, Mather K, Torian U, Engle RE, Emerson SU. 2012. Adaptation of a genotype 3 hepatitis E virus to efficient growth in cell culture depends on an inserted human gene segment acquired by recombination. J Virol 86:5697–5707. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00146-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shukla P, Nguyen HT, Torian U, Engle RE, Faulk K, Dalton HR, Bendall RP, Keane FE, Purcell RH, Emerson SU. 2011. Cross-species infections of cultured cells by hepatitis E virus and discovery of an infectious virus-host recombinant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:2438–2443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018878108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsubayashi K, Kang JH, Sakata H, Takahashi K, Shindo M, Kato M, Sato S, Kato T, Nishimori H, Tsuji K, Maguchi H, Yoshida J, Maekubo H, Mishiro S, Ikeda H. 2008. A case of transfusion-transmitted hepatitis E caused by blood from a donor infected with hepatitis E virus via zoonotic food-borne route. Transfusion 48:1368–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsubayashi K, Nagaoka Y, Sakata H, Sato S, Fukai K, Kato T, Takahashi K, Mishiro S, Imai M, Takeda N, Ikeda H. 2004. Transfusion-transmitted hepatitis E caused by apparently indigenous hepatitis E virus strain in Hokkaido, Japan. Transfusion 44:934–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawlotsky JM. 2014. Hepatitis E screening for blood donations: an urgent need? Lancet 384:1729–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]