Abstract

We investigated the mode of action underlying lytic inactivation of HIV-1 virions by peptide triazole thiol (PTT), in particular the relationship between gp120 disulfides and the C-terminal cysteine-SH required for virolysis. Obligate PTT dimer obtained by PTT SH cross-linking and PTTs with serially truncated linkers between pharmacophore isoleucine–ferrocenyltriazole-proline–tryptophan and cysteine-SH were synthesized. PTT variants showed loss of lytic activity but not binding and infection inhibition upon SH blockade. A disproportionate loss of lysis activity vs binding and infection inhibition was observed upon linker truncation. Molecular docking of PTT onto gp120 argued that, with sufficient linker length, the peptide SH could approach and disrupt several alternative gp120 disulfides. Inhibition of lysis by gp120 mAb 2G12, which binds at the base of the V3 loop, as well as disulfide mutational effects, argued that PTT-induced disruption of the gp120 disulfide cluster at the base of the V3 loop is an important step in lytic inactivation of HIV-1. Further, PTT-induced lysis was enhanced after treating virus with reducing agents dithiothreitol and tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine. Overall, the results are consistent with the view that the binding of PTT positions the peptide SH group to interfere with conserved disulfides clustered proximal to the CD4 binding site in gp120, leading to disulfide exchange in gp120 and possibly gp41, rearrangement of the Env spike, and ultimately disruption of the viral membrane. The dependence of lysis activity on thiol–disulfide interaction may be related to intrinsic disulfide exchange susceptibility in gp120 that has been reported previously to play a role in HIV-1 cell infection.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

The HIV-1 glycoprotein complex (Env), containing the only virus-specific proteins on the virion surface, consists of exposed gp120 subunits that engage CD4 receptors on T cells to initiate cell entry. Conformational changes within Env gp120 are required to promote co-receptor binding after CD4 engagement. The series of Env conformational rearrangements enables exposure of the fusion peptide of the Env transmembrane protein, gp41, and its insertion into the host cell membrane. Subsequent refolding of gp41 heptad repeat regions forms a six-helix bundle to allow membrane fusion and transmission of the viral genome into the host cell.1

The importance of Env gp120 for host cell recognition and infection makes it a critical target for therapeutic interventions. In this context, we previously identified a class of peptide triazole (PT) HIV-1 Env gp120 antagonists that potently inhibit cell infection.2 The peptide triazole design initially was conceived3 as a means to convert the low-activity 12p1 dual receptor site antagonist peptide4 into a more effective inhibitor. Structure–activity analyses3 showed that hydrophobic substituents on the triazoles were particularly effective, with the ferrocenyl derivative being the most effective. The high-potency ferrocenyl triazole was included in the PTTs investigated in the current work to ensure experiments in a maximum-activity condition. PTs contain a tripeptide sequence, IXW (X = triazole-proline), which is critical for binding.2 This tripeptide motif targets PT binding to gp120 in a two-cavity region5 that includes the Phe43 binding pocket, utilizing the conserved residues in this region to inhibit recognition of both CD4 and co-receptors. At the molecular level, PT binding appears to conformationally entrap soluble gp120 in an inactive state and prevents formation of the gp120 bridging sheet domain, thereby preventing CD4 and co-receptor engagement.6,7 The inactive conformation of gp120 is unique in that it does not resemble the flexible unliganded state nor is it highly structured as seen in the CD4-bound conformation of gp120.6,7 At the virus level, the inhibitors cause gp120 shedding from the HIV-1 virion, resulting in an inactive residual virus particle.8 A PT variant, denoted 1 (KR13, R-I-N-N-I-X-W-S-E-A-M-M-βA-Q-βA-C-CONH2; Figure 1A), containing a C-terminal cysteine, not only inhibits CD4 and mAb 17b (co-receptor surrogate) binding to gp120 with nanomolar IC50 values and causes gp120 shedding but also causes lysis of HIV-1 virions as determined by release of the internal capsid protein p24.8,9 Importantly, PTs without the cysteine-SH group did not cause lysis.8 Intriguingly, the p24 release activity of 1 was shown to have strong mechanistic similarities to virus–cell fusion, in particular the need in both cases for gp41 six-helix bundle formation.5 The different effects of 1 on the virus, including inhibition of receptor site binding and lysis, all are due to the fundamental binding event of the PT IXW pharmacophore to gp120. Hence, defining the mechanistic properties of the PTT thiol on lysis is a critical part of determining the overall cascade of PTT virological effects. However, the structural mechanism of thiol group action in PTTs has remained undetermined.

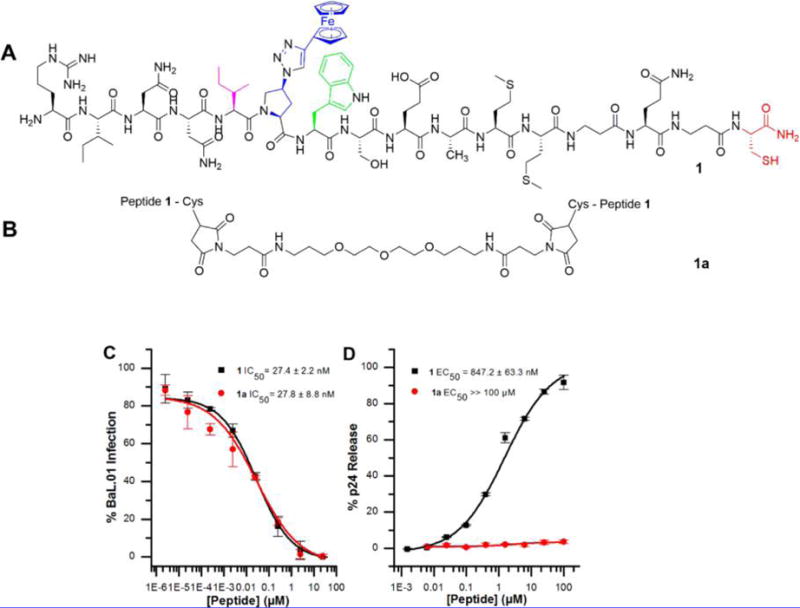

Figure 1.

Structures and dose response of the effects of 1 and 1a on HIV-1BaL pseudovirus antiviral functions. (A) 1 is the lytic parent peptide of the library of peptide triazole thiol truncates. All PTs contain the signature pharmacophore, isoleucine (magenta)–azidoproline (blue)–tryptophan (green). (B) 1a is composed of Bis-Mal dPeg conjugated to the C-terminal sulfhydryl groups of two monomers of 1. (C) Inhibition of cell infection analyzed using a single round pseudotyped assay. The IC50 values show that 1 and 1a inhibit HIV-1BaL infection to the same extent. (D) Relative p24 release measured using ELISA. The calculated EC50 values for 1 and 1a were and 1065 ± 40 nM and >100 000 nM respectively. The data were normalized using untreated virus as a negative control (<5% p24 release), and p24 release observed with 1% Triton X treated virus was taken as 100% p24 content. Sigmoidal curve fits of data were obtained using Origin v.8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA). Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean, n = 3.

In the current study, we sought to determine the mechanism by which peptide triazole thiols induce HIV viral lysis by investigating the structural requirements and role of the PTT SH group. Chemical synthesis of an obligatory dimer and PTT linker variants confirmed that lysis requires the free SH in PTTs. PTT-induced virus lysis occurs by engagement of the linker-tethered SH with specific conserved disulfide groups in gp120. Inhibition of lysis by mAb 2G12 but not by several other gp120 ligands, along with a simulation of PTT binding to gp120 by docking to the gp120 crystallographic structure, suggested that the peptide SH group could approach several gp120 disulfides, including C378–C445 (C3), C385–C415 (C4), and C296–C331 (V3), which are localized near the CD4 binding pocket. Analysis of the effects of reducing agents on lysis led to the view that PTTs not only disrupt a specific disulfide bond but more generally cause disulfide exchange in the Env protein. PTTs maintained lytic functions in two recombinantly derived gp120 single-disulfide mutant viruses. In contrast, p24 release was not observed with gp41 disulfide deficient mutant virus, arguing that an intact disulfide is required in the loop between the N- and C-helices of the gp41 ectodomain. The importance of thiol–disulfide interaction in lysis may be related to the role of gp120 disulfide exchange in HIV cell infection.10–12

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Role of the Peptide Triazole SH Group Probed by Characterizing an Obligatory Dimer

We previously reported that a subclass of peptide triazoles containing C-terminal sulfhydryl groups causes cell-independent disruption of HIV-1BaL virions as indicated by release of the luminal p24 protein.9 We further found that the terminal cysteine residue was required for luminal p24 release but was not essential for gp120 shedding, a phenotype displayed by non-sulfhydryl containing peptides (10, HNG156, and 12, UM15) and a sulfhydryl-blocked derivative (11, KR13b).8 Previously we synthesized a control peptide denoted KR13S, which contained a scrambled IXW pharmacophore (IWX). KR13S did not bind gp120, inhibit HIV infection, or induce either gp120 shedding or p24 release.8 Taken together, these results showed that the IXW amino acid sequence is required for PT binding to HIV Env and the lytic effect is specifically promoted by the gp120 binding-pharmacophore and C-terminal cysteine. In the current investigation, we started by confirming the requirement for the free SH group by determining the viral inhibition and virolytic properties of the obligate dimer, 1a (KR13 dimer) formed by cross-linking the cysteine residues of 1 monomers through thiol Michael addition using a bismaleimide linker13,14 (Figure 1 and Supporting Figures S2 and S3). We compared the effects of 1a with control peptide 1 on gp120 binding, HIV-1 infectivity, and p24 release. Peptide binding to gp120 was determined using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) interaction analysis, with KD values for 1 and 1a found to be 2.71 ± 1.4 and 3.02 ± 0.9 nM, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1). Antiviral effects of 1a were measured using HIV-1BaL pseudotyped virions; the dimer was found to be a powerful inhibitor of HIV-1 infection, comparable to 1 (Figure 1C). In contrast, we found that 1a did not induce p24 release (Figure 1D). This result demonstrated the need for a free-SH group in PTs for virolysis.

Functional Properties of Truncated Peptide Triazole Thiols

To evaluate the importance of the spatial relationship between the pharmacophore sequence IXW and the SH group in PTTs, we synthesized a series of truncated peptides (2–9) derived from peptide 1 by previously established methods (Supporting Table S1, Figure 2, and Supporting Figures S4–21). We tested the gp120 binding activities of the peptides by competition ELISA with soluble CD4 (sCD4) or monoclonal antibody 17b, a co-receptor surrogate (Table 1, Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 28). The activities of representative peptide truncates were further validated by sCD4 competition using the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) method (Supporting Figure S28B), with IC50 values obtained for 1–9 given in Table 1. The results showed that all of the peptides exhibited substantial gp120 binding activities, except for the shortest peptide, 9, for which binding activity was finite but reduced.

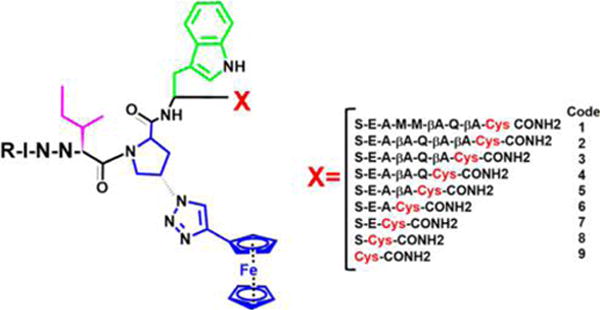

Figure 2.

Structures of PTTs with serially truncated linker between IXW pharmacophore and C-terminal cysteine. The pharmacophore sequence, composed of isoleucine (magenta)–triazole-proline (blue)–tryptophan (green).

Table 1.

| code | designation | ELISA, IC50 (nM)

|

SPR sCD4 IC50 (nM) | inhibition of infection, IC50 (nM) | Gp120 shedding, EC50 (nM) | p24 release, EC50 (nM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sCD4 | 17b | ||||||

| 1 | KR13 | 28 ± 4 | 32 ± 6 | 93 ± 4 | 53 ± 19 | 32 ± 20 | 1065 ± 40 |

| 2 | HL01 | 110 ± 8 | 153 ± 14 | 237 ± 8 | 143 ± 45 | 140 ± 37 | 1800 ± 91 |

| 3 | HL02 | 123 ± 51 | 142 ± 25 | 153 ± 47 | 114 ± 40 | a | 1321 ± 26 |

| 4 | HL03 | 199 ± 23 | 198 ± 35 | 172 ± 66 | 197 ± 38 | 183 ± 37.9 | 2202 ± 61 |

| 5 | HL04 | 183 ± 13 | 227 ± 30 | a | 286 ± 13 | a | 4762 ± 73 |

| 6 | LB05 | 207 ± 29 | 195 ± 41 | a | 469 ± 19 | a | 26730 ± 82 |

| 7 | LB04 | 218 ± 10 | 713 ± 144 | 344 ± 70 | 554 ± 7 | 288 ± 133 | 33210 ± 89 |

| 8 | LB03 | 331 ± 11 | 939 ± 186 | 379 ± 16 | 550 ± 63 | 523 ± 97.6 | 38420 ± 49 |

| 9 | LB02 | 589 ± 74 | 906 ± 128 | 2913 ± 798.8 | 7030 ± 2200 | 9366 ± 563 | ≫500000 |

Not determined.

Figure 3.

(A) ELISA competition of CD4-gp120 antagonism potencies of truncated peptide triazole thiols. (B) Dose response of the effects of peptide triazole thiol truncates on HIV-1BaL pseudovirus. Inhibition of cell infection was analyzed using a single round pseudotyped assay. The IC50 values are reported in Table 1. The data show that serially truncated PTTs progressively lose antiviral potency as the distance between the IXW pharmacophore and sulfhydryl group is shortened. (C) p24 release from HIV-1BaL pseudotyped virus caused by PTTs. Relative p24 release was measured using ELISA. The data were normalized using untreated virus as a negative control (<5% p24 release), and p24 release observed with 1% Triton X treated virus was taken as 100% p24 content. Sigmoidal curve fits of data were obtained using Origin v.8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA). Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean, n = 3. (D) Variation of EC50/IC50 ratio values for p24 release vs gp120 binding as a function of linker length. The IC50 values for gp120 binding were from inhibition of virus cell infection (closed squares) or CD4 competition ELISA (open squares).

Peptide effects on virus were determined by treating gradient-purified HIV-1BaL with increasing concentrations of peptide in cell infection, gp120 shedding, and p24 release analyses. As with gp120 binding (Table 1, Figure 3A, and Supporting Figure S28), inhibition of infection (Figure 3B, Table 1) and gp120 shedding (Table 1) activities of most truncates except 9 were substantial. However, the p24 release results (Figure 3C) showed a more severe loss of virus lysis activity for peptides with increasing linker truncations. Of note, the peptide potencies for infection inhibition were significantly greater compared with their respective potencies in lysis assays. This is likely because the assays were carried out under quite different conditions. In the lysis assay, peptides were incubated with virus for 30 min, whereas for infection assays, peptides were incubated with virus and cells for 1 day. Therefore, the potencies may be related to the respective kinetics of viral inhibitions and p24 release.

Discontinuous Relationship of Lysis to Binding

The differential effects of peptide linker truncation on p24 release versus binding-dependent properties were correlated as a function of distance between the IXW active core and free cysteine SH group. The results (Supporting Table S2, Figure 3D) showed that decreasing the distance between the tryptophan residue and SH caused disproportionate loss of p24 release activity. The strong dependence of lysis activity on linker length is consistent with a direct effect of the PT-SH on specific sites within gp120. One explanation for this behavior is that the free SH group of PTTs interacts with one or more gp120 disulfides. HIV-1 Env consists of 10 conserved disulfides, 9 of which are located within gp120 and the tenth in gp41.9,15–17 We speculate that, in order to reach specific gp120 disulfides, a minimum distance between IXW and the free SH group is required.

Molecular Docking and Predicted Location of SH Group

A previously derived molecular dynamics simulated model of peptide triazole–gp120 binding has suggested that the hydrophobic motif (IXW) binds to specific residues within and close to the CD4 binding cavity of gp120.5,18 However, this model for peptide triazoles utilized phenyltriazole instead of the ferrocenyltriazole found in high affinity peptide triazole thiols, including those reported in the present study. The use of the phenyl substituent enabled the use of CHARMM, which possessed surface desolvation and energy parameters for a phenyl moiety and not those for ferrocene rings. In the current study, we sought to identify possible gp120 contact sites of the PT thiol group as well as the location and trajectory of the C-terminus with one of the ferrocenyl PTT truncates examined here. The enhanced docking model in Figure 4 shows 8 in complex with core gp120. Docking simulation models more accurately predict binding orientation between ligand and protein when the ligand is small and rigid. Therefore, 8 was used in the docking simulation because it was the most truncated peptide still lytically active. This model predicts that the pharmacophore binds in a site overlapping the CD4 binding site. Interestingly, the C-terminus of 8 was localized similarly distant from several disulfide regions of gp120.

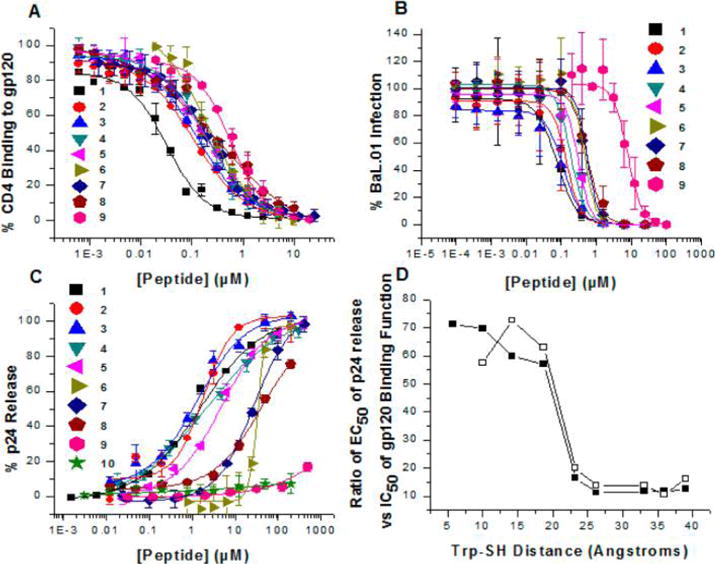

Figure 4.

Molecular docking simulation of PTT, 8, in complex with gp120. The structure of 8 (carbons shown in cyan) was docked onto gp120 resulting in the binding model shown. Peptide 8 binds in a site overlapping the CD4 pocket (surface shown in gray), with the C-terminal cysteine (SH shown as CPK) trajectory to the conserved disulfide cluster (blue, C296–C331; yellow, C385–C418; violet, C378–C445; orange, C119–C205), which encompasses possible sites of disulfide interaction. The model shows that the peptide SH group is well solvated and with the conformational flexibility can reach any of the disulfide bridges shown.

Protein Ligand Effects

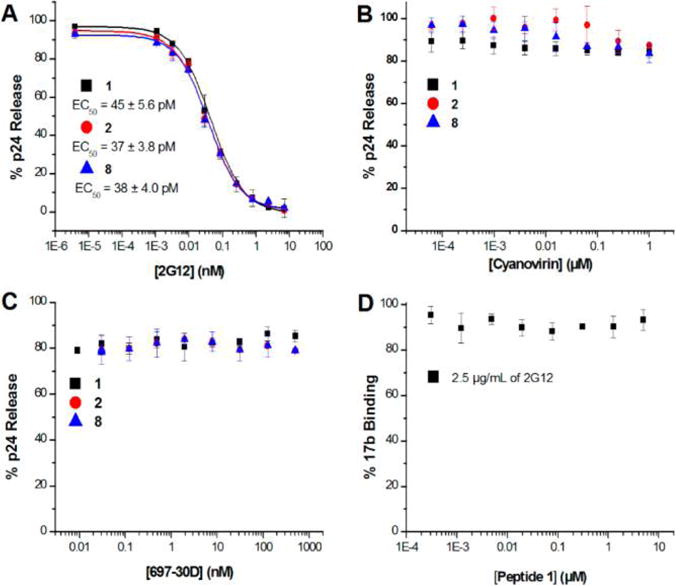

We addressed whether p24 release activity of PTTs could be affected by gp120 binding at some or all of the above disulfide-containing regions by proteins ligands that do not inhibit PT interaction. The broadly neutralizing gp120 antibody 2G12 has previously been shown to bind to the mannose-rich epitope at the base of the gp120 V3 loop19 but to not affect PT binding20 (Figure 5D). Inhibition assays with 2G12 were performed with 1 (positive control), 2 (the longest of the truncated virolytic peptides), and 8 (the shortest peptide truncate that still causes observable p24 release). These inhibition assays showed that 2G12 inhibits the lytic ability of all three PTTs (Figure 5A). We also evaluated the effect of cyanovirin-N, a lectin that binds high-mannose glycans in the gp120 outer domain, which has been observed before to not compete with peptide triazole binding.20 In contrast to 2G12, cyanovirin-N did not inhibit p24 release induced by the PTTs 1, 2, or 8 (Figure 5B). Based on the docking model of Figure 6, another possible site of disulfide interaction is located in the V1/V2 loop encompassing the disulfide C119–C205. We evaluated the effect of the neutralizing antibody, 697-30D, which is specific for the V2 region of gp120 and recognizes an epitope that spans the region 164–1946 and overlaps the C119–C225 disulfide. The results of p24 release inhibition analysis showed that 697-30D did not affect the lytic ability of PTTs of varying lengths (Figure 5C). To confirm that 2G12 inhibition of lysis was not due to inhibition of six-helix bundle formation, we performed an infection assay in which the onset of six-helix bundle formation was delayed by low temperature until after 2G12 treatment. The results of this control analysis are given in Supporting Information Figure S32. In contrast to T20, a fusion inhibitor that blocked infection, 2G12 did not prevent infection. These data confirm that the 2G12 inhibition of lysis is due to direct binding to gp120 and that the most likely gp120 disulfides participating in disruption by the PTT SH are those in the V3 region close to the 2G12 binding site.

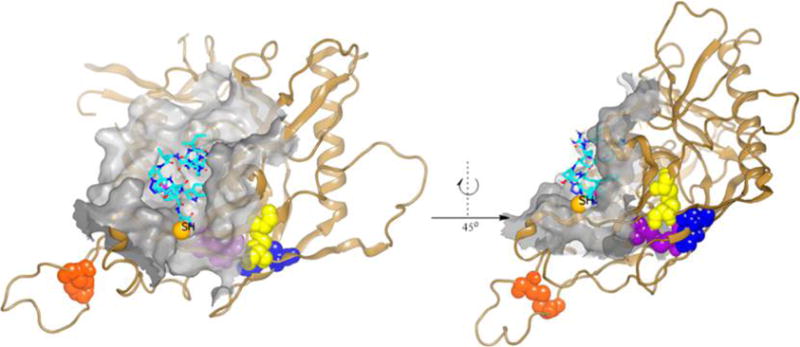

Figure 5.

Effect of protein ligands on p24 release by PTTs. (A) Effect of conformational antibody 2G12 on p24 release. HIV-1BaL pseudovirus was treated in the presence and absence of 10 μM 1, 14 μM 2 or 50 μM 8 and serial dilution of 2G12 starting at 10 nM. (B) Effect of carbohydrate binding protein, cyanovirin, on p24 release. HIV-1BaL pseudovirus was treated in the presence and absence of the respective EC80 concentrations of 1, 2, and 8 and serial dilution of cyanovirin starting at 1 μM. (C) Effect of conformational antibody, 697-30D, on p24 release. HIV-1BaL pseudovirus was treated in the presence and absence of 10 μM 1, 14 μM 2 or 50 μM 8 and serial dilution of 697-30D starting at 1 μM. (D) Effect of 2G12 on 1 binding to gp120: 17b Sandwich ELISA assay performed with constant concentration of 2G12(2.5 μg/mL) and serial dilutions of 1.

Figure 6.

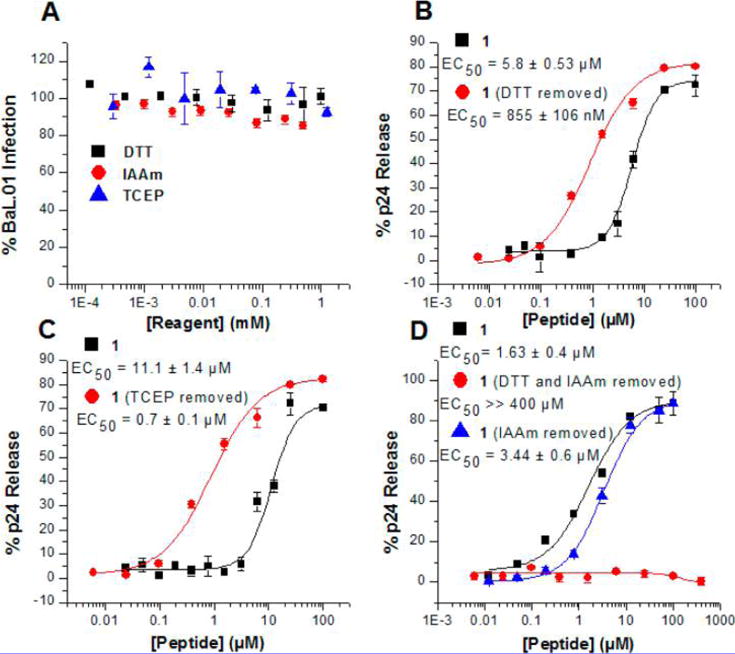

Effect of sulfhydryl reagents on PTT induced p24 release. (A) Effect of sulfhydryl reagents on HIV-1BaL infectivity: DTT, TCEP, and IAAm treated HIV-1BaL virions. Sulfhydryl reagents were removed by centrifugation prior to adding to HOS cells to test infectivity. (B) Effect of HIV-1BaL treatment and removal of DTT, followed by 1 treatment and p24 release analysis. (C) Effect of HIV-1BaL treatment and removal of TCEP, followed by 1 treatment and p24 release analysis. (D) Effect of HIV-1BaL treatment of DTT serial dilutions and removal with subsequent treatment of 0.02 mM IAAm, followed by 1 treatment and p24 release analysis.

Effects of Sulfhydryl Reagents on p24 Release by KR13

Previous work has shown that cysteine reduction and alkylation impairs the HIV-1 infection process.21 Such observations and the detrimental effects of oxidoreductase inhibition on infection efficiency of several enveloped viruses have suggested that Env protein disulfide exchange could play a role in viral entry.10,11,15,22 In view of the importance of the thiol in PTT and proximity to gp120 disulfides, we evaluated the possible role of Env disulfide exchange in PTT-induced virolysis using sulfhydryl reduction and blocking for the test case of 1. The reducing agents examined included the thiol reagent dithiothreitol (DTT)23 and the non-thiol containing tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). The alkylating reagent, iodoacetamide (IAAm), was used as an irreversible sulfhydryl blocker. These three reagents were independently found to inhibit pseudotyped HIV-1BaL infection (in agreement with prior observations15,22,24), but infection activity was regained after removal of the reagents before assays (Figure 6A). Strikingly, virolysis assays where virions were exposed to treatment with DTT or TCEP and subsequent reagent washout (“treat/wash”) showed strongly enhanced KR13-induced p24 release potencies (Figure 6B,C). As expected, the effect was specific for PTs containing an exposed C-terminal sulfhydryl group (Supplementary Figure 29). Furthermore, virions treated with DTT, washed, then treated with IAAm and washed again, were refractory to KR13 lysis (Figure 6D), even though virions similarly treated with IAAm alone and then washed were not functionally suppressed. The greater lytic activity of DTT treat/wash versus untreated viruses, taken with the effects of IAAm, suggest that initiating reduction of HIV-1 Env protein disulfide bonds, while not in itself disruptive of function, enhances the ability of the thiol group of peptide triazole thiols to more potently cause lytic inactivation. Increased KR13 lytic potency can be explained as due to potentiation of a disulfide exchange cascade through the Env protein.

Effects of Env Disulfide Mutations of KR13-Induced HIV-1BaL Lysis

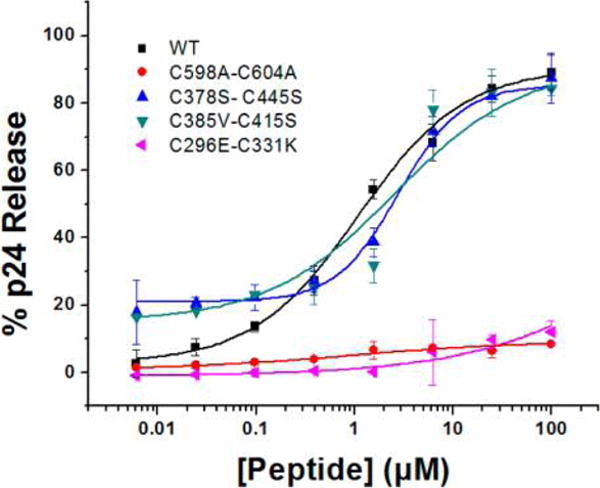

In order to assess what disulfides in Env protein could be involved in the disulfide exchange cascade occurring in PTT-induced lysis, we mutated several individual disulfide bonds in both gp120 and gp41. As explained above, MD simulation of gp120 binding (Figure 4) predicted that the thiol group of PTTs would be proximal to gp120 V3 region disulfide bonds C378–C445, C385–C415, and C296–C331, and hence one or more of the latter could be sites for initial disulfide disruption. We were able to prepare viruses carrying the mutations C378S–C445S, C385V–C415S, and C296E–C331K. We also recombinantly modified the gp41 disulfide bond, C598–C604, with the C598A–C604A mutant, based on the prior observation8 that KR13-induced lysis involves rearrangement of the gp41 protein into a six-helix bundle8 and that such rearrangement could depend on the gp41 disulfide. Mutant HIV-1BaL virions were gradient-purified and quantified for gp120 and p24 content. Although the mutant HIV-1BaL virions were not infectious, they were found to bind to CD4 and 17b by virus ELISA (Supporting Figure S31). Strikingly, KR13-induced p24 release analysis revealed that, while mutant HIV-1BaL C378S–C445S and C385V–C415S virions showed p24 release comparable to the WT HIV-1BaL virions, KR13-induced virolysis of the HIV-1BaL mutants C296E–C331K and C598A–C604A were greatly suppressed (Figure 7). These data show that disulfide exchange triggered by 1 appears to use selective gp120 disulfide engagement in an ordered manner and that preservation of both gp120 C296–C331 and gp41 C598–C604 disulfides is important for the Env rearrangements that ultimately cause lytic inactivation by this PTT.

Figure 7.

Effect of HIV-1BaL disulfide mutations on p24 release by 1. Effect of HIV-1BaL mutations C378S–C445S (cyan), C385V–C415S (blue), and C598A–C604A (red) on p24 release. Relative p24 release was measured using ELISA. The data were normalized using untreated virus as a negative control (<5% p24 release), and p24 release observed with 1% Triton X treated virus was taken as 100% p24 content. Sigmoidal curve fits of data were obtained using OriginPro8 (OriginLab). Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean, n = 3.

Overall, the investigation reported here was aimed to determine the role of the thiol group of PTTs in the lytic inactivation of HIV-1. Functional analysis of obligate dimer 1a (Figure 1) confirmed the hypothesis5 that the free peptide-SH rather than an oxidized disulfide dimer is the functional form of PTTs. Results obtained with PTT linker truncates, flexible docking, protein ligand effects, and Env disulfide mutations all demonstrated that the free thiol engages specific Env protein disulfides during lysis. Further, sulfhydryl reagent effects on lysis argued that Env disulfide engagement by PTT triggers a disulfide exchange cascade in the Env protein spike. These findings show that in the HIV-1 lytic inactivation process, the PTT thiol takes advantage of the sensitivity of Env disulfides to thiol–disulfide exchange, a property that has been reported to play a role in the infection processes of HIV-1 and other enveloped viruses.11,15,16,25–28

We surmised that if interactions occur between the PTT SH group and specific gp120 disulfides, virolysis would be dependent on sufficient length of the linker between the PT binding pharmacophore and C-terminal cysteine-SH contact. We examined a library of truncated peptide triazole thiols (Figure 2, Supporting Table S1) derived from parent peptide 1 by serially shortening the linker. The most shortened peptides evaluated, including 9 with no linker, retained finite gp120 binding affinity and inhibited virus cell infection (Figure 3, Table 1). In contrast, we observed a disproportionate loss of virolysis activity with shortened linkers, in particular peptides with three linker residues or fewer (Figure 3D). The truncation results argued that there is a minimal required spacing between the IXW pharmacophore and thiol group to enable contact with specific gp120 disulfides.

We examined which of the 10 conserved gp120 disulfides and possibly the single gp41 disulfide were the primary sites of PTT thiol contact using a combination of computational simulation, effects of protein ligands, and disulfide mutations. Flexible docking of PTT truncate 8 to gp120 in an F105-bound conformation5,18 showed that the IXW pharmacopore docked with the tryptophan residue located as expected in the recently revealed two-cavity site in gp120.2 The SH group in the docked complex was located similarly distanced from several disulfide groups of gp120, including C119–C205 in the V1/V2 loop region (left side in Figure 4) and C378–C445 (C3), C385–C415 (C4), and C296–C331 (V3) (right side in Figure 4). The docked structure confirmed the location of the IXW pharmacophore close to residues found to be important for binding by mutagenesis2,5,7 However, the model left open which disulfide interactions with the PTT SH could be the cause of lytic inactivation. The ability of the monoclonal antibody 2G12, which binds to the base of the gp120 V3 loop, to suppress lysis (Figure 5A) argued that V3 loop disulfides could be a site of initial engagement by PTT thiol. In contrast to 2G12, no inhibition of p24 release was observed (Figures 5B,C) with cyanovirin-N, which binds to glycans distal to the V3 loop region, or with mAb 697-30D, which binds close to V1/V2 disulfides.6,19,29–31

The importance of specific V3 loop disulfide involvement for PTT SH contact was further revealed by examining pseudoviruses with disulfide mutations. Mutation of C378–C445 or C385–C415 in HIV-1BaL had no effect on lysis. In contrast, C296E–C331K mutation had a strong suppressive effect, allowing the conclusion that this disulfide is an important initial contact for PTT thiol in its lytic inactivation function. Importantly, retention of the gp41 disulfide also was found to be required for lytic inactivation, as shown by the observation that the C598A–C604A mutant was not lysed by 1. Given the location of the PTT in the docking model (Figure 4), the gp120 disulfide C296–C331 is likely the initial contact for PTT thiol, while the involvement of gp41 disulfide C598–C604 is more indirect.

Evidence obtained in this work with thiol reducers suggested that the lysis-inducing PTT thiol interaction with specific gp120 disulfides likely occurs not simply by single disulfide bond reductions but instead by more extensive Env disulfide disruption. We found that reduction by either DTT or TCEP, followed by excess reagent removal, did not cause significant dose-dependent reduction in virus infectivity (Figure 6A). In contrast, the treated and washed viruses obtained with both reducing reagents showed increased sensitivity to PTT-induced p24 release compared with untreated viruses (Figure 6B,C). This sensitivity was blocked by treating the DTT- and TCEP-reduced viruses with IAAm prior to PTT exposure (Figure 6D), showing that the enhancement of lysis depended on the availability of reduced sulfhydryl groups in the protein and further that specific reduced sulfhydryl groups are likely required to trigger the lytic process. The overall results with reducers argue that reduction of one or more Env disulfides activates a disulfide exchange cascade triggered by 1 and that it is this cascade that ultimately causes Env protein conformational transformation and consequent lytic inactivation.

Disulfide exchange triggered by PTT, combined with requirements of both gp120 C296–C331 and gp41 C598–C604 in lysis, lead us to the hypothesis that exchange likely is initiated by C296–C331 interaction with PTT thiol and requires intact C598–C604 to enable lysis. For the latter, our data do not exclude the possibility that gp41 disulfide reduction could occur as a required step during lysis induced by 1. The gp41 disulfide occurs in the loop between the gp41 N- and C-helices that form the six-helix bundle hairpin known to occur as a key step in virus–cell fusion. Since six-helix bundle formation also has been shown before to occur during PTT-induced lysis,8 one possibility is that the gp41 disulfide stabilizes the six-helix bundle for lysis. A similar role of gp41 disulfide in stabilizing bundle formation for fusion and consequent infection has been argued.27,28

Disulfides are known to be important for HIV-1 gp120 folding, CD4 binding, and infectivity.17,32 The susceptibility of gp120 to undergo disulfide exchange has been observed before and may be carried out by cell-associated oxidoreductases.16,33–36 In gp120, the disulfide bonds C378–C445, C385–C415, and C296–C331 are often referred to as the “CD4 exposed disulfide cluster” because of their proximity to the CD4 binding site.37 This close relationship between the disulfides and CD4 binding site make them possible sites of disruption through disulfide exchange by membrane-associated PDI.15 The work reported here demonstrates sensitivity of this same disulfide cluster of gp120 to PTT lytic inactivaton of HIV-1.15,16,33

Prior findings for several viruses suggest that disulfide bond cleavage regulated by disulfide exchange is an important event in cell entry. Several lentiviruses rely on redox-induced changes to their disulfides to ensure efficient viral membrane fusion and subsequent infection.28 Enveloped viruses such as murine leukemia virus (MLV), human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1), and HIV-1 contain a conserved disulfide bond, located in a Cys-X-X-Cys motif in their respective fusion proteins that is required for membrane fusion.38–40 Further, the effects of sulfhydryl reagents on the fusogenic activity of several viruses, including MLV, HTLV-1,38–40 human cytomegalovirus (CMV), Sindbis (SINV) virus, and HIV10,15,26,41 have implied a role for disulfide exchange in the cell infection process.

Sulfhydryl-containing peptide triazoles are novel due to their ability to cause lytic inactivation of HIV-1. Improved understanding of the minimum sequence needed for virolysis will help guide further design of PTTs as drug leads, for example, using an emerging peptidomimetic approach.42 In addition, further investigation of PTT-induced disulfide exchange could shed light on the intrinsic mechanism of structural rearrangements, initiated by virus Env–cell receptor interactions, that lead to fusion, entry, and infection.

METHODS

Reagents

Escherichia coli strain XL-10 gold (Agilent) and Stbl2 cells (Invitrogen) were products of Novagen Inc. (Madison, WI). Thermostable DNA polymerase (PfuUltra) was obtained from Stratagene Inc. (La Jolla, CA). Custom-oligonucleotide primers were supplied by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). DNA plasmids encoding HIV-1BaL Env (catalog no. 11445) and NL4-3 R− E− Luc+ were obtained from the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, and were a kind gift of Dr. J Mascola and Dr. N Landau, respectively. All other reagents used were of the highest analytical grade available.

Peptide Synthesis and Click Conjugation

All sequences and denotations of peptides reported are given in Supplementary Table 1. Peptides were synthesized manually by stepwise solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) on a Rink amide resin (NovaBiochem) with a substitution value of 0.25 mmol/g as described previously.2 The 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) group was employed for protection of the α-amino group during coupling steps. All α and β Fmoc amino acid derivatives and coupling reagents were purchased from Chem-Impex International, Inc. Side chain protecting groups were triphenylmethyl (Trt) for asparagine, tert-butyl (tBu) for serine, and tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc) for tryptophan. Synthesis grade solvents were used in all procedures. Coupling of each residue was carried out using N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl) uronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU)/hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) in dimethylformamide (DMF). Four equivalents of each Fmoc protected amino acid was used for coupling. The click chemistry reaction resulting in the [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction of ethynyl ferrocene (Sigma-Aldrich) was carried out by an on-resin method.43 Completed peptides were cleaved from the resin using a cocktail of 95:2:2:1 trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/1, 2-ethanedithiol/water/thioanisole. Crude peptides were purified using a semipreparative column (Phenomenex Jupiter 10 μ C4, 300 Å, 250 mm × 10 mm, 3 mL/min) by HPLC (Beckman Coulter, System Gold 126 solvent module and 168 detector, 280 nm) with gradient between 95:5:0.1 and 5:95:0.1 water/acetonitrile/trifluoroacetic acid. Peptide purity and mass were confirmed using an analytical HPLC column (Phenomenex Luna 5 μ C18, 100 Å, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 1 mL/min) and MALDI-TOF mass spectrophotometry, respectively.

Chemoselective Ligation of Bis-maleimide and KR13 (1)

KR13 (1; 2.084 mg, 2.5 equiv) was dissolved into 1000 μL of degassed phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.6) prior to the addition of 0.574 mg of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP·HCl, 5 equiv; Thermo Fisher Scientific) to the reaction vessel. Compound 1 was reduced with TCEP for 30 min under vacuum and nitrogen purging. Bis-Mal-dPeg3 (400 μL, 0.522 g; Quanta Biodesign Limited) dissolved into 1000 μL of ACN (1 equiv) was added dropwise to the reaction vessel. The ligation process was monitored by analytical HPLC (Phenomenex Luna 5 μ C18, 100 Å, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 1 mL/min) over a 30–95% ACN gradient, as the reaction mixture was stirred under N2 at 37 °C. After 2 h, another 200 μL of Bis-Mal-dPeg was added to the reaction, and the reaction continued for 3 h. Peptide purity and mass of the final ligation product, KR13 dimer (1a), were confirmed using an analytical HPLC (Phenomenex C18) and MALDI-TOF mass spectrophotometry, respectively.

Pseudoviral Production and Inhibition Assays

Modified human osteosarcoma cells engineered to express CD4 and CCR5 (HOS.T4.R5), as well as the vectors expressing pNL4-3.Luc+ R− E− and the CCR5-targeting spike protein BaL.01 gp160 were obtained through the NIH AIDS Repository as a kind gift from Dr. Nathaniel Landau and Dr. John Mascola, respectively. The pseudovirus was produced by cotransfecting HEK-293T cells with the envelope expressing plasmid, HIV-1BaL.01 strain, and the envelope-deficient plasmid, pNL4-3.Luc+ R− E− provirus. Post-transfection (72 h), pseudovirus-containing supernatants were collected, filtered through a 0.45 μM syringe filter, and concentrated using an Amicon spin filter (100 kDa MWCO) prior to being loaded on an iodixanol gradient ranging from 6% to 20% in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Samples were spun for 2 h at 112 000g on an SW41 rotor in a Beckman ultracentrifuge at 4 °C. Fractions containing the pseudovirus were collected, aliquoted in serum-free medium, and frozen at −80 °C. Prior to experiments, pseudovirus samples were titered for p24 content and infectivity as described below. The single-round pseudoviral infection luciferase reporter assay was conducted as previously described.20 Briefly, when testing peptide inhibition potencies, the viral stocks were first incubated with serial dilutions of the peptide at 37 °C for 30 min and then added to 96 well tissue culture plates with HOS.T4.R5 cells, preseeded for 24 h at 8000 cells per well. Two controls (virus with no peptide, 100%, and buffer only, no virus, 0%) were used to establish the window for this assay. After 48 h infection, with a growth medium wash step 24 h post-treatment, the cells were lysed with passive lysis buffer (Promega) followed by three freeze–thaw cycles. Luciferase assays were performed using 1 mM D-luciferin salt (AnaSpec) as substrate and detected on a 1450 Microbeta liquid scintillation and luminescence counter (Wallac and Jet). Nonlinear regression analysis was performed using Origin v.8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA) to calculate the IC50 values. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed as relative infection with respect to cells infected with virus in the absence of inhibitor (100% infected).

Sulfhydryl Reagent “Treat/Wash” Viral Infection Assays

The viral stocks were first incubated with serial dilutions of dithiothreitol (DTT), iodoacetamide (IAAm), and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) at 37 °C for 30 min then transferred to 30 kDa MWCO 0.5 mL centrifuge filters (Amicon) and spun at 2000g at 37 °C for 7 min. After the 7 min spin, 165 μL of 1× PBS was added to the samples and mixed thoroughly via pipetting. The centrifugation and PBS addition were repeated 3 times; at this point, the treated virus was added to 96 well tissue culture plates and tested for infectivity. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed as relative infection with respect to cells infected with virus in the absence of inhibitor (100% infected).

Competition ELISA

The ability of peptides to inhibit sCD4 and mAb 17 binding to HIV-1YU2 gp120 was analyzed by competition ELISA.2 First, 100 ng of HIV-1YU2 gp120 per well was adsorbed to wells of a 96-well high binding polystyrene plate (Fisher Scientific) for 12 h at 4 °C. The HIV-1YU2 gp120 was removed from the plate and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Research Products International, Corp) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 2 h at 25 °C, followed by plate washing with PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 v/v (PBS-T). For the CD4 competition experiments, 30 nM sCD4 was added to each well in the presence of increasing concentrations of peptide. This and all subsequent incubation steps were done in 0.5% BSA in PBS. After 1 h incubation period, the plate was washed with PBS-T followed by addition of biotinylated anti-CD4 antibody (eBioscience) at a 1:5000 dilution, and the plate incubated for an additional 1 h at 25 °C. After plate washing, streptavidin-bound HRP (AnaSpec) was added at a 1:5000 dilution and again incubated for 1 h at RT. To determine effectiveness of peptides to inhibit the co-receptor surrogate 17b antibody binding to gp120, 15 nM mAb 17b was added to the plate-immobilized gp120 in the presence of increasing concentrations of peptide. After 1 h incubation at RT, the plate was washed with PBS-T, followed by the addition of streptavidin-bound horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-human antibody (CHEMICON), which was incubated for 1 h at RT. The extent of HRP conjugate binding was detected in both assays by adding o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) (Sigma-Aldrich) reagent for 30 min followed by measuring optical density (OD) at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices). IC50 values were determined using nonlinear regression analysis with Origin v.8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA).

Optical Biosensor Binding Assays

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) kinetic interaction experiments were performed on a Biacore 3000 (GE) optical biosensor instrument. A CM5 sensor chip was derivatized by amine coupling, using N-ethyl-N-(3-(dimethylamino)-propyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride/N-hydroxy-succinimide and conjugating with either soluble CD4 or 2B6R (antibody to human IL-5 receptor α) as controls at a density of 2000 RU. For sCD4 competition experiments, serial dilutions of the peptides with a constant concentration of HIV-1YU2 WT gp120 (200 nM) were injected over the sCD4 surface at a flow rate of 100 μL/min with a 2.5 min association phase and a 2.5 min dissociation phase. Surfaces were regenerated with 10 mM HCl injection for 3 s. All experiments were conducted at 25 °C in filtered and degassed PBS, pH 7.4, containing 0.005% Tween 20. SPR data analyses were performed using BIAEvaluation 4.1.1 software (GE Healthcare). The responses from the buffer injection and responses from the control surface to which the mAb 2B6R was immobilized were subtracted to account for nonspecific binding. Experimental data were fit to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model. The average kinetic parameters generated from a minimum of three data sets were used to define the equilibrium dissociation (KD) constant. The evaluation method for SPR inhibition data included a calculation for the inhibitor concentration at 50% of the maximal response (IC50). The inhibition curve was converted into a calibration curve by the use of a fitting function. Data were fit to a four-parameter sigmoidal equation in Origin v.8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA).

Expression and Purification of Cyanovirin (CVN)

The CVN plasmid was transformed in BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells, and cells were scaled up in LB media. Protein expression was induced using 1 mM isopropyl-B-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 9 h at 30 °C. In order to perform extraction of periplasmic proteins from the bacterial membrane, the cell suspension was pelleted and lysed before being sonicated using a microtip probe (Misonix 3000). The sonicated sample was spun down for 30 min at 10 000g to separate the bacterial debris from the protein containing supernantant. The latter was then fractionated by gravity flow affinity chromatography with nickel nitriloacetic acid (Ni-NTA) beads (Qiagen), followed by gel filtration with a 26/60 Superdex 200 prep-grade column (GE Healthcare) using an AKTA fast protein liquid chromatograph (FPLC, GE Healthcare). Western blotting of the Ni-NTA and gel filtration elution fractions along with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis were used to track protein content of eluates and functionality, respectively. Fractions containing target proteins were concentrated, and buffer was exchanged to phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, using a 5000 molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) spin filter (Amicon). The final protein was examined on a 15% SDS-PAGE gel using Commassie blue and silver staining. Western blot analysis using a rabbit anti-CVN (Biosyn Inc.) was used to confirm the presence of the CVN component. The final concentration was determined using absorbance at 280 nm and an extinction coefficient at 280 nm of 39 740 M−1 cm−1.

Virolysis Assays

The ability of the peptide triazole thiols to cause virolysis of pseudotyped HIV-1BaL virus was analyzed by quantifying p24 release. An equal volume of intact pseudotyped HIV-1BaL, purified through gradient centrifugation, was added to a series of samples that contained a 1:4 serial dilution of peptide triazole thiols, as well as nonlytic 10, at working concentrations determined from the viral assays. The control samples replaced the peptide with either phosphate-buffered-saline (PBS; negative lysis control) or 1% Triton-X 100 (positive lysis control). All prepared samples were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C prior to a 2 h spin at 16 000g and 4 °C on a tabletop 5424R centrifuge (Eppendorf). The top 120-μL soluble fraction was collected and tested for p24 content by sandwich capture ELISA as follows. High binding polystyrene ELISA plates (Fisher Scientific) were coated with 50 ng/well of mouse anti-p24 (Abcam) followed by blocking with 3% BSA for 2 h at RT. This was removed by flicking prior to the addition of the soluble fractions obtained from the peptide treated HIV-1BaL in 0.5% BSA and incubated for 2 h. The p24 in the soluble fractions was quantified using 1:5000 dilutions of anti-rabbit p24 (Abcam) and then anti-rabbit IgG fused to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Invitrogen). The activity of the HRP conjugate binding was determined by adding 200 μL/well of o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) (Sigma-Aldrich) reagent for 30 min followed by measuring absorbance at 450 nm using a plate reader (Tecan, Infinite F50). The PBS treated virus signals were subtracted; signals were then plotted as a function of p24 release, using the fully lysed virus control, treated with 1% Triton X-100, as the 100% value. Nonlinear regression analysis was performed using Origin v.8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA) to calculate the EC50 values. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Assays for Protein Inhibition of Virolysis

The neutralization EC50 values of gp120 protein ligands were used as the starting concentrations for measuring inhibition of virolysis.6,29 Serial dilutions of 2G12 antibody starting at 1 mg mL−1, 1 μM cyanovirin, or 100 μg/mL 697-30D antibody were incubated with the EC80 concentration of peptide, namely, 10 μM for 1, 14 μM for 2, and 50 μM for 8. The peptide and protein were added to a 1:4 working dilution of the purified pseudotyped HIV-1BaL virions for 30 min at 37 °C. The soluble fraction was separated, and the extent of p24 release was determined by the same protocol as the sandwich ELISA protocol described above. Virus in PBS was the negative control, while virus in 1% Triton-X 100 was the positive control. Quantified values from triplicate assays were plotted as a function of p24 released compared with the positive control. These values were fit using Origin v.8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA) to determine EC50 values.

2G12 Mechanism of Action Infection Assay

To allow HIV viral engagement with CD4 and co-receptors yet halt fusion, the initial part of the assay was performed under chilled conditions at 4 °C. The latter part of the assay was conducted at 37 °C to facilitate viral fusion. Viral stocks, growth medium, and HOS.T4.R5 cells, preseeded for 24 h at 8000 cells per well, were prechilled to 4 °C. The virus was then incubated with the prechilled cells for 4 h at 4 °C. The media was removed, and cells were washed twice with chilled growth medium to remove unbound virus. Then serial dilutions of 2G12 prepared in chilled medium and 1× PBS were incubated with cells at 30 min increments at 4 °C, then 23 °C, followed by a 37 °C incubation for 24 h, which concluded with a growth medium wash step. After 48 h of infection, the cells were lysed with passive lysis buffer (Promega) followed by three freeze–thaw cycles. The fusion inhibitor peptide, enfuvirtide (T20), added to a control group of wells, was used as a control to verify that at the time of 2G12 addition, six-helix bundle formation had not occurred. The luciferase activity for the infection assay was performed as described above. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed as relative infection with respect to cells infected with virus in the absence of inhibitor (100% infected).

Assays for Sulfhydryl Reagent Inhibition of Virolysis

DTT (1 mM), TCEP (1 mM), and IAAm (0.02 mM) were incubated with a 1:4 working dilution of purified pseudotyped HIV-1BaL virions for 30 min at 37 °C. Reagents were removed from virions by centrifugation at 2000g for 7 min at 37 °C in 30 kDa centrifugation filters (Amicon). The retained HIV-1BaL virions were washed with 165 μL of PBS, and this was repeated three times. The viral particles were then treated with serial dilutions of 1, 11, and 12 for 30 min at 37 °C. The soluble fraction was separated, and the extent of p24 release was determined by the same protocol as the sandwich ELISA protocol described above. Virus in PBS was the negative control, while virus in 1% Triton-X 100 was the positive control. Quantified values from triplicate assays were plotted as a function of p24 released compared with the positive control. These values were fit using Origin v.8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA) to determine EC50 values.

Design and Construction of Various HIV-1BaL Env Mutants

Wild-type (WT) HIV-1BaL Env construct in a pcDNA3.1D vector (NIH AIDS reagent program) was used to prepare HIV-1BaL Env substitution mutants. Mutants of HIV-1BaL Env were created using Quick-Change site-directed mutagenesis reagents and methods (Stratagene). The primers used for mutagenesis were custom synthesized at IDT DNA. The following forward primers and their reverse complements were used in the 5′–3′ direction: C598A forward, 5′-ggg gat ttg ggg tgc ctc tgg aaa act c; C598A-reverse, 5′-gag ttt tcc aga ggc acc cca aat ccc c; C604A forward, 5′-gga aaa ctc atc gcc acc act gcc g; C604A reverse, 5′-cgg cag tgg tgg cga tga gtt ttc c; C385V forward, 5′-ggg aat ttt tct acg cta att caa cac aac tg; C385V reverse, 5′-cag ttg tgt tga att agc gta gaa aaa ttc cc; C415S forward, 5′-cac aat cac act ccc agc cag aat aaa ac; C415S reverse, 5′-cac aat cac act ccc agc cag aat aaa ac; C378S forward, 5′-gtg acg cac agt ttt aat agt gga ggg gaa; C378S reverse, 5′-cac tgc gtg tca aaa tta tca cct ccc ctt; C445S forward, 5′-ccc atc aga gga caa att aga agt tca tca aa; C445S reverse, 5′-ggg tag cct gtt taa tct tca agt agt tt; C296E forward, 5′-gaa tct gta gaa att aat gag aca aga ccc aac aac; C296E reverse, 5′-gtt gtt ggg tct tgt ctc att aat ttc tac aga ttc; C331K forward, 5′-ata aga caa gca cat aag aac ctt agt aga gca; C331K reverse, 5′-tgc tct act aag gtt ctt atg tgc ttg tct tat. Mutagenesis was confirmed by sequencing (Genewiz Inc.) using the BGHR primer or a custom-made primer that spans the Env cassette (IDT).

Mutant HIV-1BaL Binding to CD4 and 17b ELISA

The ability of the HIV-1BaL mutants C296E–C331K, C378S–C445S, C385V–C415S, and C598A–C604A to bind sCD4 and mAb 17 was analyzed by ELISA.2 Gradient-purified viruses were added to a 100 kDa concentrator (Amicon) followed by centrifugation at 2000g at 4 °C for 3 min on a tabletop 5424R centrifuge (Eppendorf). The retained HIV-1BaL virions were washed with PBS. The wash step was repeated three times, and the flow through was discarded. Concentrated and washed virus (100 μL) was added to 100 μL of fixative mixture comprised of 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 2% paraformaldehyde. The resulting mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 15 min followed by the addition of 100 μL of 0.1 M glycine followed by another incubation at 4 °C for 15 min to quench the reaction. HIV-1BaL virus-fixative mixture was added to 100 kDa concentrators (Amicon) and spun at 2000g for 3 min at 4 °C to perform a buffer exchange with PBS. HIV-1BaL was adsorbed at 50 μL per well to a 96-well high binding polystyrene ELISA plate (Corning) for 12 h at 4 °C with gentle rocking. The HIV-1BaL was then removed from the plate and the latter was blocked with 3% BSA (Research Products International, Corp) in PBS for 2 h at 25 °C, followed by a plate washing step with PBS-T. For the CD4 binding experiments, 50 μL/well of 30 nM sCD4 in 0.5% BSA in PBS was added to the plate and incubated for 1 h at 25 °C. This and all subsequent incubation steps were done in 0.5% BSA in PBS. After a 1 h incubation period, the plate was washed with PBS-T followed by addition of of biotinylated anti-CD4 (OKT4) antibody (eBioscience) at a 1:5000 dilution, and the plate was incubated for an additional 1 h at 25 °C. After plate washing, streptavidin-bound HRP (AnaSpec) was added at a 1:5000 dilution and again incubated for 1 h at RT. For the 17b binding experiments, 15 nM mAb 17b was added to the plate-immobilized HIV-1BaL. After a 1 h incubation at 25 °C, the plate was washed with PBS-T, followed by the addition of a horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-human antibody (CHEMICON), which was incubated for 1 h at RT. The extent of HRP conjugate binding was detected colorimetrically in both assays by adding 200 μL/well of 0.4 mg mL−1 o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in sodium citrate with perborate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min in the dark. Capsid p24 and virion-associated gp120 were quantified by ELISA and Western blot, respectively, using the concentrated virus collected after the quenching step. The optical density (OD) units generated from either CD4 or 17b binding to the pseudovirus samples were normalized based on the p24 content of each mutant and the gp120 content to allow for comparison between the mutants. Each experiment for CD4 or 17b binding contained a standard curve using sCD4 and 17b binding to monomeric HIV-1YU2 gp120 serially diluted (1:2, v/v) starting at 100 ng/mL.

gp120 Shedding Assay

Serial dilutions of peptide triazole thiols 1, 2, 4, 7, and 9 starting from 50 μM were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with a 1:4 working dilution of the purified pseudotyped HIV-1BaL virions. Next, the virus-peptide mixture was spun for 2 h at 16 000g and 4 °C on a tabletop 5424R centrifuge (Eppendorf). Negative and positive control samples included, respectively, virus in PBS and virus in 1% Triton X-100. Next, 120 μL was removed from the soluble fraction to separate the viral pellet fraction. Western blot analysis with 1:3000 dilution of anti-gp120 D7324 (Aalto) and anti-sheep IgG conjugated HRP (Life Technologies) was used to quantify the amount of viral envelope gp120 retained in the pellet. The Western blots were quantified using ImageJ software and compared with the blots for the lysed virus fraction. Data for amount of gp120 shed from virus were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis with Origin v.8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA) to determine shedding EC50 values.

OriginPro 8 Curve Fitting of Dose Dependence Data

Data analysis of dose-dependence measurements performed in this study was conducted by sigmoidal curve fitting using the Origin v.8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA) software. The formula used, which enables a sigmoidal logistic fit, was

where A1 is the initial value (0), A2 is the final value (based on the experimental data), p is the Hill coefficient, X is the concentration of the inhibitor used, and X0 is the IC50 value. The logistic nature of the fitting algorithm allows the p value to float freely. The differences in cooperativity that we observe in the fitted plots likely arise from complexities of the peptide–virion and virion–cell interactions, a situation that is different than simple protein–protein and protein–peptide interactions.

Molecular Docking

Peptide Preparation for Docking

Peptide 8 was prepared and drawn using VIDA 4.2.0 (Openeye Scientific Software, Santa Fe, NM, http://www.eyesopen.com). The ferrocene containing peptide was energy-minimized using the MM2 force field (ChemBio3D Ultra 13.0) with RMS gradient of 0.001 and 104 alterations. The minimized structure was saved as a pdb file, and autodock tools graphical interface (Autodock tools 1.5.6rc3)44 was used to prepare the minimized structure of 8 for docking.

Flexible Docking

The starting point for 8 flexible docking to gp120 was the previously developed model of PT interactions using the F105 bound crystal structure of gp120 (PDB code 3HI1).45 The gp120 structure was extracted from this complex and was further energy refined using Szybki 1.8.0.2 (Openeye Scientific Software, Santa Fe, NM, http://www.eyesopen.com). The option (−max_iter) in Szybki was set to 106 to ensure that the added hydrogen atoms are correctly optimized. The optimized gp120 structure was then prepared by Autodock tools graphical interface (Autodock tools 1.5.6rc3),44 where nonpolar hydrogen atoms were merged, Kollman charges added, and Gasteiger charges calculated. Residue Trp112 was set to be flexible for the docking such that the indole side chain can move during the docking simulation to accommodate the bulky ferrocene moiety. The grid box for the docking search was set to 52 × 52 × 52 points for the x, y, and z dimensions with a spacing grid of 0.375 Å. Grid centers X, Y, and Z were set to 55.784, 28.301, and −21.068, respectively. AutoGrid 4.2 algorithm was used to evaluate the binding energies between the peptide and gp120 and to generate the energy maps for the docking run. For docking 8 with gp120 in a high accuracy mode, the maximum number of evaluations (25 × 106) was used. Fifty runs were generated by using Autodock 4.2 Lamarckian genetic algorithm44 for the searches. Cluster analysis was performed on docked results, with a root-mean-square tolerance of 2.0 Å. Visual inspection of the docked poses was done and compared with the mutagenesis analysis results5,46 to select a low energy representative binding mode. The complex was then typed with the CHARMM force field with Discovery Studio 4.0 software (Accelrys Software Inc., San Diego, CA, 2013) to relax the obtained pose within the protein pockets, visualized by VIDA 4.2.0 (Openeye Scientific Software, Santa Fe, NM, http://www.eyesopen.com).

Acknowledgments

We thank Openeye Scientific Software (Openeye Scientific Software, Santa Fe, NM, http://www.eyesopen.com) for providing a free academic license of their software package.

Funding

This work was supported by the following grants: NIH P01GM56550, NIH F31AI108485 Ruth L. Kirchstein Award (L.D.B.), and Schlumberger Foundation Faculty of the Future Fellowship Award (A.R.B.)

ABBREVIATIONS

- Boc

tert-butyloxycarbonyl

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovaries

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Env

HIV envelope gp160

- Fmoc

9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl

- HAART

highly active anti-retroviral therapy

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- HBTU

N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)uronium hexafluorophosphate

- HOBT

hydroxybenzotriazole

- HRP

horse radish peroxidase

- IXW

isoleucine–ferrocenyltriazole-proline–tryptophan

- Ni-NTA

nickel nitriloacetic acid

- OPD

O-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

- PT

peptide triazole

- PTT

peptide triazole thiol

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- TCEP

Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine HCl

- tBu

tert-butyl

- Trt

triphenylmethyl

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00381.

Peptide mass spectra and RP-HPLC chromatograms and functional characterization data (PDF)

Accession Codes

PDB code for F105 bound gp120 is 3HI1.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umashankara M, McFadden K, Zentner I, Schon A, Rajagopal S, Tuzer F, Kuriakose SA, Contarino M, Lalonde J, Freire E, Chaiken I. The active core in a triazole peptide dual-site antagonist of HIV-1 gp120. ChemMedChem. 2010;5:1871–1879. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopi HN, Tirupula KC, Baxter S, Ajith S, Chaiken IM. Click Chemistry on Azidoproline: High-Affinity Dual Antagonist for HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein gp120. ChemMedChem. 2006;1:54–57. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200500037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrer M, Harrison SC. Peptide Ligands to Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 gp120 Identified from Phage Display Libraries. J Virol. 1999;73:5795–5802. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5795-5802.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aneja R, Rashad AA, Li H, Kalyana Sundaram RV, Duffy CA, Bailey L, Chaiken IM. Peptide Triazole Inactivators of HIV-1 Utilize a Conserved Two-Cavity Binding Site at the Junction of the Inner and Outer Domains of Env gp120. J Med Chem. 2015;58:3843–3858. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorny MK, Moore JP, Conley AJ, Karwowska S, Sodroski J, Williams C, Burda S, Boots LJ, Zolla-Pazner S. Human anti-V2 monoclonal antibody that neutralizes primary but not laboratory isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:8312–8320. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8312-8320.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biorn AC, Cocklin S, Madani N, Si Z, Ivanovic T, Samanen J, Van Ryk DI, Pantophlet R, Burton DR, Freire E, Sodroski J, Chaiken IM. Mode of action for linear peptide inhibitors of HIV-1 gp120 interactions. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1928–1938. doi: 10.1021/bi035088i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastian AR, Contarino M, Bailey LD, Aneja R, Moreira DR, Freedman K, McFadden K, Duffy C, Emileh A, Leslie G, Jacobson JM, Hoxie JA, Chaiken I. Interactions of peptide triazole thiols with Env gp120 induce irreversible breakdown and inactivation of HIV-1 virions. Retrovirology. 2013;10:153. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bastian AR, Kantharaju McFadden K, Duffy C, Rajagopal S, Contarino MR, Papazoglou E, Chaiken I. Cell-free HIV-1 virucidal action by modified peptide triazole inhibitors of Env gp120. ChemMedChem. 2011;6:1335–1339. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glomb-Reinmund S, Kielian M. The role of low pH and disulfide shuffling in the entry and fusion of Semliki Forest virus and Sindbis virus. Virology. 1998;248:372–381. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulvey M, Brown DT. Formation and rearrangement of disulfide bonds during maturation of the Sindbis virus E1 glycoprotein. J Virol. 1994;68:805–812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.805-812.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerutti N, Killick M, Jugnarain V, Papathanasopoulos M, Capovilla A. Disulfide Reduction in CD4 Domain 1 or 2 Is Essential for Interaction with HIV Glycoprotein 120 (gp120), which Impairs Thioredoxin-driven CD4 Dimerization. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:10455–10465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.539353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Hu S, Xi Z, Zhang L, Luo S, Cheng JP. Chiral Amine Thiourea-Promoted Enantioselective Michael Addition Reactions of 3-Substituted Benzofuran-2(3H)-ones to Maleimides. J Org Chem. 2010;75:8697–8700. doi: 10.1021/jo101832e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu J, Zhou WJ, Liu F, Loh TP. Organocatalytic and Enantioselective Direct Vinylogous Michael Addition to Maleimides. Adv Synth Catal. 2008;350:1796–1800. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryser HJ, Levy EM, Mandel R, DiSciullo GJ. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus infection by agents that interfere with thiol-disulfide interchange upon virus-receptor interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4559–4563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stantchev TS, Paciga M, Lankford CR, Schwartzkopff F, Broder CC, Clouse KA. Cell-type specific requirements for thiol/disulfide exchange during HIV-1 entry and infection. Retrovirology. 2012;9:97. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Anken E, Sanders RW, Liscaljet IM, Land A, Bontjer I, Tillemans S, Nabatov AA, Paxton WA, Berkhout B, Braakman I. Only five of 10 strictly conserved disulfide bonds are essential for folding and eight for function of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4298–4309. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emileh A, Tuzer F, Yeh H, Umashankara M, Moreira DR, Lalonde JM, Bewley CA, Abrams CF, Chaiken IM. A model of peptide triazole entry inhibitor binding to HIV-1 gp120 and the mechanism of bridging sheet disruption. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2245–2261. doi: 10.1021/bi400166b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calarese DA, Scanlan CN, Zwick MB, Deechongkit S, Mimura Y, Kunert R, Zhu P, Wormald MR, Stanfield RL, Roux KH, Kelly JW, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Katinger H, Burton DR, Wilson IA. Antibody domain exchange is an immunological solution to carbohydrate cluster recognition. Science. 2003;300:2065–2071. doi: 10.1126/science.1083182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFadden K, Fletcher P, Rossi F, Kantharaju Umashankara M, Pirrone V, Rajagopal S, Gopi H, Krebs FC, Martin-Garcia J, Shattock RJ, Chaiken I. Antiviral Breadth and Combination Potential of Peptide Triazole HIV-1 Entry Inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1073–1080. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05555-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDougal JS, Nicholson JK, Cross GD, Cort SP, Kennedy MS, Mawle AC. Binding of the human retrovirus HTLV-III/LAV/ARV/HIV to the CD4 (T4) molecule: conformation dependence, epitope mapping, antibody inhibition, and potential for idiotypic mimicry. J Immunol. 1986;137:2937–2944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandel R, Ryser HJ, Ghani F, Wu M, Peak D. Inhibition of a reductive function of the plasma membrane by bacitracin and antibodies against protein disulfide-isomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4112–4116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleland WW. Dithiothreitol, a New Protective Reagent for SH Groups*. Biochemistry. 1964;3:480–482. doi: 10.1021/bi00892a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin YJ, Zhang X, Cai CY, Burakoff SJ. Alkylating HIV-1 Nef – a potential way of HIV intervention. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:26–26. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eissmann K, Mueller S, Sticht H, Jung S, Zou P, Jiang S, Gross A, Eichler J, Fleckenstein B, Reil H. HIV-1 Fusion Is Blocked through Binding of GB Virus C E2D Peptides to the HIV-1 gp41 Disulfide Loop. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glomb-Reinmund S, Kielian M. The Role of Low pH and Disulfide Shuffling in the Entry and Fusion of Semliki Forest Virus and Sindbis Virus. Virology. 1998;248:372–381. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiu J, Ashkenazi A, Liu S, Shai Y. Structural and Functional Properties of the Membranotropic HIV-1 Glycoprotein gp41 Loop Region Are Modulated by Its Intrinsic Hydrophobic Core. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:29143–29150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.496646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashkenazi A, Viard M, Wexler-Cohen Y, Blumenthal R, Shai Y. Viral envelope protein folding and membrane hemifusion are enhanced by the conserved loop region of HIV-1 gp41. FASEB J. 2011;25:2156–2166. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-175752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huskens D, Ferir G, Vermeire K, Kehr JC, Balzarini J, Dittmann E, Schols D. Microvirin, a Novel α(1,2)-Mannose-specific Lectin Isolated from Microcystis aeruginosa, Has Anti-HIV-1 Activity Comparable with That of Cyanovirin-N but a Much Higher Safety Profile. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24845–24854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.128546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balzarini J, Van Laethem K, Peumans WJ, Van Damme EJM, Bolmstedt A, Gago F, Schols D. Mutational Pathways, Resistance Profile, and Side Effects of Cyanovirin Relative to Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Strains with N-Glycan Deletions in Their gp120 Envelopes. J Virol. 2006;80:8411–8421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00369-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bewley CA. Solution Structure of a Cyanovirin-N:Manα1–2Manα Complex. Structure. 2001;9:931–940. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clements GJ, Price-Jones MJ, Stephens PE, Sutton C, Schulz TF, Clapham PR, McKeating JA, McClure MO, Thomson S, Marsh M, et al. The V3 loops of the HIV-1 and HIV-2 surface glycoproteins contain proteolytic cleavage sites: a possible function in viral fusion? AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1991;7:3–16. doi: 10.1089/aid.1991.7.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerutti N, Mendelow BV, Napier GB, Papathanasopoulos MA, Killick M, Khati M, Stevens W, Capovilla A. Stabilization of HIV-1 gp120-CD4 Receptor Complex through Targeted Interchain Disulfide Exchange. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25743–25752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.144121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthias LJ, Yam PTW, Jiang XM, Vandegraaff N, Li P, Poumbourios P, Donoghue N, Hogg PJ. Disulfide exchange in domain 2 of CD4 is required for entry of HIV-1. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:727–732. doi: 10.1038/ni815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auwerx J, Isacsson O, Söderlund J, Balzarini J, Johansson M, Lundberg M. Human glutaredoxin-1 catalyzes the reduction of HIV-1 gp120 and CD4 disulfides and its inhibition reduces HIV-1 replication. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1269–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reiser K, Francois KO, Schols D, Bergman T, Jörnvall H, Balzarini J, Karlsson A, Lundberg M. Thioredoxin-1 and protein disulfide isomerase catalyze the reduction of similar disulfides in HIV gp120. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wyatt R, Thali M, Tilley S, Pinter A, Posner M, Ho D, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Relationship of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 third variable loop to a component of the CD4 binding site in the fourth conserved region. J Virol. 1992;66:6997–7004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.6997-7004.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li K, Zhang S, Kronqvist M, Wallin M, Ekström M, Derse D, Garoff H. Intersubunit Disulfide Isomerization Controls Membrane Fusion of Human T-Cell Leukemia Virus Env. J Virol. 2008;82:7135–7143. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00448-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallin M, Ekström M, Garoff H. Isomerization of the intersubunit disulphide-bond in Env controls retrovirus fusion. EMBO J. 2004;23:54–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinter A, Kopelman R, Li Z, Kayman SC, Sanders DA. Localization of the labile disulfide bond between SU and TM of the murine leukemia virus envelope protein complex to a highly conserved CWLC motif in SU that resembles the active-site sequence of thiol-disulfide exchange enzymes. J Virol. 1997;71:8073–8077. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.8073-8077.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirazimi A, Mousavi-Jazi M, Sundqvist VA, Svensson L. Free thiol groups are essential for infectivity of human cytomegalovirus. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(11):2861–2865. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-11-2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rashad AA, Kalyana Sundaram RV, Aneja R, Duffy C, Chaiken I. Macrocyclic Envelope Glycoprotein Antagonists that Irreversibly Inactivate HIV-1 before Host Cell Encounter. J Med Chem. 2015;58:7603–7608. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gopi HN, Tirupula KC, Baxter S, Ajith S, Chaiken IM. Click chemistry on azidoproline: high-affinity dual antagonist for HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. ChemMedChem. 2006;1:54–57. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200500037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen L, Do Kwon Y, Zhou T, Wu X, O’Dell S, Cavacini L, Hessell AJ, Pancera M, Tang M, Xu L, Yang ZY, Zhang MY, Arthos J, Burton DR, Dimitrov DS, Nabel GJ, Posner MR, Sodroski J, Wyatt R, Mascola JR, Kwong PD. Structural Basis of Immune Evasion at the Site of CD4 Attachment on HIV-1 gp120. Science. 2009;326:1123–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.1175868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tuzer F, Madani N, Kamanna K, Zentner I, LaLonde J, Holmes A, Upton E, Rajagopal S, McFadden K, Contarino M, Sodroski J, Chaiken I. HIV-1 Env gp120 structural determinants for peptide triazole dual receptor site antagonism. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Genet. 2013;81:271–290. doi: 10.1002/prot.24184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]