Abstract

Purpose of review

This review examines thresholds for treatment of traditional cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors among RA patients and whether RA-specific treatment modulates cardiovascular risk.

Recent findings

There are substantial data demonstrating an increased CVD risk among patients with RA. Both traditional CVD risk factors and inflammation contribute to this risk. Recent epidemiologic studies strengthen the case that aggressive immunosuppression with biologic DMARDs, such as TNF antagonists, is associated with a reduced risk of CVD events. However, to data, there are no randomized controlled trials published regarding the management of CVD in RA.

Summary

Epidemiologic evidence continues to accumulate regarding the relationship between the effects of traditional CVD risk factors and RA-specific treatments on CV outcomes in RA. The field needs randomized controlled trials to better guide management.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, risk stratification, coronary, treatment

Introduction

The risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is increased in rheumatoid arthritis (RA)[1–5], but no disease-specific treatment strategies have been agreed on. RA increases CVD morbidity by 1.5 - 2-fold compared to the general population[4,6*], with recent evidence supporting the notion that the mortality gap between patients with RA and those in the general population has widened[7]. Many factors contribute to the elevated CVD risk in RA, but it cannot be explained by traditional cardiovascular risk factors alone [8–11]. RA-specific factors –immune dysregulation, systemic inflammation, plaque instability, impaired coronary reserve, elevated thrombotic markers, or specific treatments (i.e. oral glucocorticoids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs)–likely also contribute to the increased CVD risk. Thus, traditional CVD risk factors and RA specific risk factors must be addressed to improve CV outcomes.

In this review, we examine: 1) whether thresholds for prevention and treatment of traditional cardiovascular risk factors should be altered in RA patients and 2) how RA-specific treatment modulates CVD risk.

Should Thresholds for Treatment of Traditional CVD Risk Factors be Altered in RA Patients?

Prior studies show that the prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors is increased in RA patients. Several traditional risk factors, such as dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), physical inactivity, advanced age, male gender, family history of CVD, cigarette smoking, and altered BMI predict CVD in RA patients[12,13]. As well, HTN, elevated LDL, and DM often go untreated or undertreated in this population [14**, 15*,16]. Whereas obesity is widely appreciated as a CVD risk factor in the general population and RA, rheumatoid cachexia may also confer an elevated CVD risk in RA patients [17]. Recent cardiology and rheumatology management guidelines acknowledge the higher risk of CVD in RA patients[18,19], but what remains unclear is whether treatment thresholds in RA patients should be altered to account for these CVD risk factors. In this section, we examine the elevated risk conferred by various traditional CVD risk factors and provide recommendations regarding management.

Dyslipidemia

Despite the increased risk of CVD in RA patients, the prevalence of dyslipidemia does not appear to differ significantly between RA patients and the general population[10]. Lipid levels may be altered by RA disease activity although the data is conflicting. In early RA, some studies demonstrate decreased levels of total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels [20,21], whereas others demonstrate increased levels of TC, LDL, and high density lipoprotein (HDL) levels[22,23]. Although reports of lipid profiles in patients with established RA vary, growing evidence suggests that lower TC and LDL levels result in paradoxically elevated CVD risk in RA patients[24,25*]. The majority of recent studies of lipid profiles in RA patients show that tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors and tocilizumab worsen lipid levels[26–29*]. As well, a recent study found that hydroxychloroquine may improve the atherogenic profile[30*].

Statin use in RA patients has been demonstrated to decrease TC and LDL levels in a randomized placebo-controlled trial [31]. A population-based retrospective study using a cohort from Scotland demonstrated that statin therapy was associated with reduced CV events and all-cause mortality in primary prevention [32*]. Lipid-lowering effects with statin treatment were similar in RA and non-RA control groups in patients randomized to atorvastatin or simvastatin therapy over a five-year period [33*]. A recent study noted that RA patients discontinuing statin therapy experienced an increased risk of myocardial infarction, although the results of observational “stopping trials” are difficult to interpret [34*]. Observational studies are unlikely to provide all of the answers. To this end, a randomized placebo-controlled study of atorvastatin in approximately 3,000 RA patients is in progress (TRACE-RA; http://www.dgoh.nhs.uk/tracera/http://www.dgoh.nhs.uk/tracera/). This study randomized patients with slight elevation in LDL (100–130 mg/dL) to test whether a more aggressive lipid treatment strategy than what is recommended in the general population is warranted [35].

Until results from this study are available, we recommend annual lipid profile screening and adherence to the current general population guidelines.

Diabetes

While DM is a clear risk factor for CVD in the general population, its influence on future CVD risk in RA patients is less clear. Although there are strong epidemiological data supporting an association between RA and insulin resistance[36], studies including diabetes as a covariate did not find a statistically significant relationship with CVD, although several were underpowered[1, 8, 10, 37]. In the QUEST-RA study, diabetes emerged as an independent risk factor in multivariate analyses but only for stroke[38]. A recent prospective study reported that diabetes mellitus was significantly predictive of a new CV event in patients with early RA[39*].

Given these conflicting data, at least annual screening of hemoglobin A1c in patients with active disease, chronic corticosteroid use, or those at high risk for CVD seems warranted. Treatment targets for DM should adhere to general population standards.

Hypertension

Studies assessing the prevalence of HTN in RA do not suggest an increase in risk compared to the general population[40*]. After disease onset, hypertension appears to be more common among patients with RA compared to those without [41]. A population-based cohort study evaluating patients with newly diagnosed RA showed that the 10-year absolute risk of a CVD event rose significantly if hypertension was present[12]. A recent multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis demonstrated that rates of undiagnosed hypertension are higher in RA patients compared to a non-RA cohort[14**]. Hypertension can be particularly difficult to control in RA patients using treatment with NSAIDs, chronic corticosteroids, or DMARDs associated with increased blood pressure (i.e. leflunomide and cyclosporine)[42, 43, 44].

Given these findings, it is important to regularly monitor blood pressure levels and treat based on general population guidelines for hypertension.

Cigarette smoking

Cigarette smoking is considered one of the strongest environmental risk factors for RA incidence and progression, particularly in genetically predisposed individuals[45]. In RA patients, cigarette smoking is associated with anti-citrullinated peptide antibody production and increases the risk of joint erosions and extra-articular manifestations[46]. In seropositive RA males, cigarette smoking is associated with increased disease severity [47]. However in a population-based incidence cohort of subjects with RA, cigarette smoking imparted less risk for the development of CVD in RA patients compared to the non-RA group[10].

Smoking cessation should be emphasized in RA patients, particularly to improve disease activity but also given the probable CVD benefit.

Body Mass Index (BMI)

While obesity is a well-documented traditional CVD risk factor in the population, low BMI is also shown to be associated with increased risk of death due to CVD in RA patients[48, 17]. Although it remains unclear whether individuals with RA have an elevated BMI compared to the general population[49], obese patients with RA tend to have worse disease activity and a significantly elevated CVD risk[50,51]. Rheumatoid cachexia may be equally important [52], although a recent small observational prospective study did not demonstrate low BMI to be a significant predictor of new CV events [39*].

Given the elevated CVD risk, regular monitoring of BMI and encouragement of healthy diet and regular exercise for RA patients is likely to be of significant CVD benefit.

Does Treatment of RA Modulate Cardiovascular Risk?

Based on the accumulating evidence of an increased association of systemic inflammation with increased CVD risk [39*, 53–55, 56*, 57, 58*, 59], the implication is that better control of disease activity in RA patients will result in improved CVD outcomes. However, it is not currently known whether the relationship between systemic inflammation and CVD risk is causal or simply an association. To date, no randomized controlled trial has directly evaluated whether anti-inflammatory agents reduce CVD event rates, in either RA or the general population. While a number of studies have evaluated the effects of whether effective treatment of RA improves cardiovascular outcome, these studies are conflicted and are unfortunately limited by study design and a low number of events. In this section, we attempt to highlight the most recent literature focusing on how individual treatment options may specifically modulate active inflammation and CVD risk factors in RA patients.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

The relationship of NSAIDs to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in RA patients remains controversial. Several earlier clinical trials demonstrated a higher risk of adverse CVD outcomes for patients treated with selective COX2 inhibitors compared to placebo[60–63]. Epidemiological studies of CVD outcomes in large population-based groups have also suggested increased toxicity of non-selective NSAIDs[64–66]. Subgroup analyses demonstrated that factors such as age>80 years, hypertension, prior CV events, presence of RA or COPD may identify patients at high risk[67]. However, little data exists regarding the CVD safety of NSAID use in cohorts of patients with chronic inflammatory disease. A previous meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials in patients with osteoarthritis and RA found that use of non-selective NSAIDs, compared to placebo, had no significant effect on CVD events in these patients [68]. Similar results from a primary care-based inception cohort of patients with inflammatory polyarthritis showed that NSAID use does not appear to be associated with increased cardiovascular disease or all-cause mortality[69]. While there are conflicting data regarding these agents’ safety in RA, one should employ similar caution regarding use of NSAIDs in RA patients as with the general population.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid studies demonstrate contradictory results regarding their impact on CVD risk. Previous studies demonstrate considerable detrimental effects of corticosteroids on blood pressure, insulin resistance, hypertension, body weight and fat distribution[70–72]. This risk appears dose-dependent, given that the use of corticosteroids in high cumulative doses has been associated with increased CVD mortality, MI, and heart failure[73]. While previous studies suggest an adverse impact on lipid profiles, corticosteroids may also have cardioprotective effects mediated by their anti-inflammatory effects. Corticosteroids may actually improve the lipid profile by increasing HDL levels and lowering the TC to HDL ratio [74–76]. Furthermore, a recent systematic literature review assessing the CVD risk in RA patients using low dose corticosteroids (defined as <10mg/day of prednisone) demonstrated weak association with CVD risk. However, a trend of increasing major CV events was identified[77].

Given the concerns raised, we suggest that corticosteroid dosing be limited to the shortest duration possible.

Methotrexate (MTX)

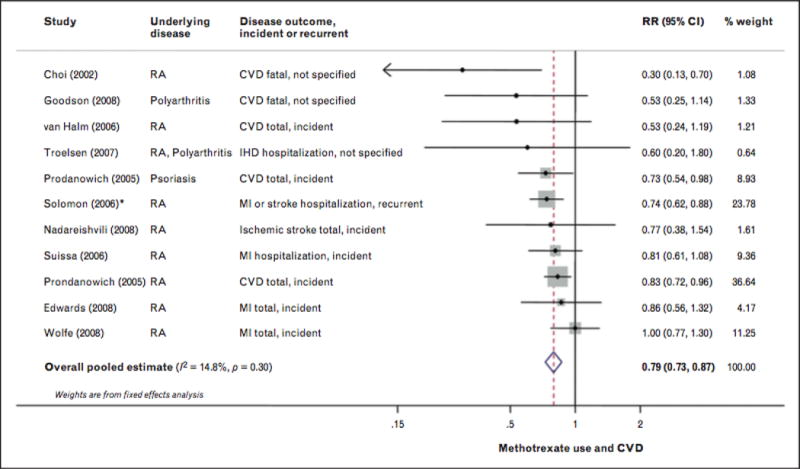

MTX has been associated with reductions in CVD [78], ranging from 15% to 85%[37, 79, 80]. However, in studies including TNF inhibitors, reductions in MTX-associated CVD have not been observed [81*,82]. Recent systematic reviews also demonstrate overall cardiovascular benefits with MTX in RA, although the results have been heterogenous[83**,84]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that MTX use among patients with systemic inflammation primarily due to RA was associated with a 21% lower CVD risk, with little evidence of between-study heterogeneity [83**] (Figure 1). The evidence for benefit is strongest for a reduction in the overall CVD morbidity and mortality and weakest for stroke outcomes. A large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial known as CIRT (Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial) is currently funded by the NIH to assess the effect of MTX (15–20 mg weekly) in the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death among patients with known prior cardiovascular disease who have DM or metabolic syndrome[85]. The potential impact of CIRT is significant in that if MTX is shown to improve CVD outcomes, this would not only lend support to the hypothesis of the significant role of inflammation in the development of CVD, but would also provide a novel treatment for patients with chronic cardiovascular disease.

FIGURE 1.

Risk for cardiovascular disease associated with methotrexate use, including eight prospective and two retrospective cohort studies, 66334 participants and 6235 events. Random-effects meta-analysis was used to calculate the overall pooled RR, in the presence of statistical between-study heterogeneity (P>0.10]. Solid diamonds and lines are study-specific RRs ond 95% Cls, respectively; the size of each box is weighted by the inverse variance of each study. Dashed line and open diamond are pooled RR and 95% CI, respectively, combining each study-specific RR. *Assessed other RA medication compared with methotrexate as the reference group. The RR of methotrexate versus other RA medications wos calculated by pooling the inverse RRs of all other RA medications, using fixed-effects meta-analysis. CI, confidence interval; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; RA, rheumatoid arthritis. Adapted from [85■■].

Until results from the CIRT are known, we recommend continuing MTX as a DMARD in RA patients, but cannot definitively comment on its CVD benefits.

TNF inhibitors

TNF-α is an inflammatory cytokine known to contribute to the pathogenesis of RA and has an atherogenic effect on the endothelial cells lining arterial walls [86]; it may contribute to vascular instability and atherosclerosis progression[87]. As a result, TNF inhibitor therapy has been postulated to have a potential cardioprotective effect. In patients with RA, recent epidemiological studies have shown conflicting results. Data from a large registry study shows significant reductions in fatal and nonfatal CVD outcomes associated with TNF inhibitors[81*]. In contrast, another study from the U.S. Veterans Administration database did not demonstrate a reduction in the rate of composite CVD endpoints, but did appear to reduce stroke risk [88*]. Similarly, a study from the Swedish Rheumatology Registry found no decrease in the risk of acute coronary syndrome with TNF-inhibitor therapy, including in a subgroup of patients with a good or moderate EULAR response [89*]. Given the known atherogenic effects of TNF-α, there has been significant literature surrounding the effect of TNF inhbitors on the lipid profile[75, 90, 91*, 92, 93*], with recent literature suggesting that these agents are associated with significant increases of TC, HDL, and TG levels, although LDL levels and the atherogenic index again remained unaffected[94*]. Therefore, the presumed cardioprotective effects of TNF inhibitors in RA patients do not seem to be explained by changes in the lipid profile, given that long-term treatment appears to have no effect on the atherogenic index or LDL levels. While increased HDL levels may offer benefit towards improved CVD outcomes, this has yet to be confirmed by prospective studies with long-term follow-up.

Among patients with RA, we recommend continuing use of TNF-inhibitors as DMARD therapy, with annual lipid screening and management based on current general population guidelines.

Non-TNF Biologic DMARDs

Newer agents in RA treatment demonstrate conflicting results regarding CVD risk. Long-term safety analysis of rituximab, a human-murine chimeric monoclonal antibody against CD20 approved for the treatment of refractory RA demonstrated no notable differences in serious CVD events during placebo-controlled periods[95,96]. Recent studies evaluating the effect of rituximab on the lipid profile and endothelial dysfunction have shown conflicting results. [97,98]. Tocilizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor, has been associated with CRP reductions within two weeks of initiation of treatment[99]. However, studies on tocilizumab demonstrate an adverse impact on lipid profiles[100,101*], with a recent meta-analysis demonstrating persistent elevations of TC, LDL, and HDL for years after initiating treatment[102]. Thus far, increased CVD events have not been demonstrated in patients treated with tocilizumab. Similarly, tofacitinib, a new oral Janus Kinase inhibitor, recently approved by the FDA for use in patients with RA, is also associated with significantly increased mean LDL levels as compared with placebo [103**]. Larger studies, with long-term follow-up are needed to determine the relationship between these newer agents and the risk of CVD. It is possible that they will have beneficial effects on CVD risk, but more data need to be collected to understand the CVD risk-benefit profile of these agents.

Conclusion

We have focused on treatment effects on CVD in patients with RA. However, targeting preventive treatments requires accurate estimation of CVD risk. Multiple studies demonstrate the limitations of general population CVD risk stratification methods among patients with RA [104**, 105, 106*], and this remains an active area of investigation. Future research is needed to develop and validate RA-specific CVD risk algorithms to provide effective primary and secondary prevention in RA patients.

We suggest clinicians maintain a high level of suspicion for CVD and its risk factors in RA. Until treatment trials have been completed, regular screening for traditional CVD risk factors, education of patients and primary care providers, and aggressive management of each risk factor is prudent. Treating to target with an aggressive DMARD strategy may also lead to reduced CVD risk. However, this is still an unproven hypothesis.

Key Points.

Substantial data demonstrates increased CVD risk among RA patients.

This review examines whether thresholds for treatment of traditional CVD risk factors should be altered among RA patients and whether RA-specific treatment modulates CVD risk.

While well-designed, randomized controlled trials are necessary, accumulating epidemiological data supports careful risk factor management and the possibility that disease suppression may reduce CVD risk in RA.

Acknowledgments

Support: Dr. Solomon’s efforts were supported by NIH K24 AR 055989.

Disclosures: Dr. Solomon also receives salary support from research grants to his institution from Amgen, Lilly, and CORRONA. He serves in unpaid roles on trials funded by Pfizer and Novartis.

References

- 1.Solomon DH, Karlson EW, Rimm EB, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in women diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003;107:1303–1307. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000054612.26458.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe F, Mitchell DM, Sibley JT, et al. The mortality of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:481–494. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han C, Robinson DW, Jr, Hackett MV, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2167–2172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon DH, Goodson NJ, Katz JN, et al. Patterns of cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1608–1612. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.050377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P, De Blasio G, et al. Preclinical impairment of coronary flow reserve in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann NY AcadSci. 2007;1108:392–397. doi: 10.1196/annals.1422.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6*.Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of incident cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1524–1529. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200726. This is a meta-analysis of controlled observational studies demonstrating a 48% increased risk of incident CVD in patients with RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez A, Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, et al. The widening mortality gap between rheumatoid arthritis patients and the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3583–3587. doi: 10.1002/art.22979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.del Rincon ID, Williams K, Stern MP, et al. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2737–2745. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2737::AID-ART460>3.0.CO;2-%23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon DH, Kremer J, Curtis JR, et al. Explaining the cardiovascular risk associated with rheumatoid arthritis: traditional risk factors versus markers of rheumatoid arthritis severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1920–1925. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.122226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez A, Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, et al. Do cardiovascular risk factors confer the same risk for cardiovascular outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis patients as in non-rheumatoid arthritis patients? Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:64–69. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.059980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brady SR, de Courten B, Reid CM, et al. The role of traditional cardiovascular risk factors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:34–40. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kremers HM, Crowson CS, Therneau TM, et al. High ten-year risk of cardiovascular disease in newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis patients: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2268–2274. doi: 10.1002/art.23650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon DH, Curhan GC, Rimm EB, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in women with and without rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3444–3449. doi: 10.1002/art.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14**.Chung CP, Giles JT, Petri M, et al. Prevalence of traditional modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison with control subjects from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:535–44. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.004. This case control study of RA patients compared to a control group from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis demonstrated that traditional cardiovascular risk factors are highly prevalent, underdiagnosed, and poorly controlled in both RA patients and the control group Hypertension was shown to be more common in the RA patients than in controls. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15*.Lindhardsen J, Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, et al. Initiation and adherence to secondary prevention pharmacotherapy after myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1496–1501. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200806. This cohort study of unselected patients with first-time MI demonstrated undertreatment with secondary prevention pharmacotherapy in RA patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toms TE, Panoulas VF, Douglas KM, et al. Statin use in rheumatoid arthritis in relation to actual cardiovascular risk: evidence for substantial undertreatment of lipid-associated cardiovascular risk? Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:683–688. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.115717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kremers HM, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, et al. Prognostic importance of low body mass index in relation to cardiovascular mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3450–3457. doi: 10.1002/art.20612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters MJ, Symmons DP, McCarey D, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:325–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.113696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:e50–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park YB, Lee SK, Lee WK, et al. Lipid profiles in untreated patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1701–1704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boers M, Nurmohamed MT, Doelman CJ, et al. Influence of glucocorticoids and disease activity on total and high density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:842–845. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.9.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Georgiadis AN, Papavasiliou EC, Lourida ES, et al. Atherogenic lipid profile is a feature characteristic of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: effect of early treatment. A prospective, controlled study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R82. doi: 10.1186/ar1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Halm VP, Nielen MM, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Lipids and inflammation: serial measurements of the lipid profile of blood donors who later developed rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:184–188. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.051672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semb AG, Kvien TK, Aastveit AH, et al. Lipids, myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the Apolipoprotein-Related Mortality RISk (AMORIS) Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1996–2001. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, et al. Lipid paradox in rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of serum lipid measures and systemic inflammation on the risk of cardiovascular disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:482–487. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.135871. This population-based RA incident cohort study examined the impact of systemic inflammation and serum lipids on CVD in RA patients, with results demonstrating an association between Inflammatory markers and increased CVD risk in RA along with a potential paradoxical relationship between lipid levels with the risk of CVD in RA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahlqvist SR, Engstrand S, Berglin E, Johnson O. Conversion towards an atherogenic lipid profile in rheumatoid arthritis patients during long-term infliximab therapy. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:107–111. doi: 10.1080/03009740500474578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Popa C, van den Hoogen FH, Radstake TR, et al. Modulation of lipoprotein plasma concentrations during long-term anti-TNF therapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1503–1507. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soubrier M, Jouanel P, Mathieu S, et al. Effects of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy on lipid profile in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:22–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29*.Singh JA, Beg S, Lopez-Olivo MA. Tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis: a Cochrane systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:10–20. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100717. This review demonstrated a decrease in RA disease activity and improved function in patients treated with tocilizumab in combination with methotrexate/DMARD Tocilizumab treatment was associated with a significant increase in cholesterol levels and occurrence of any adverse event, but no serious adverse events. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Morris SJ, Wasko MC, Antohe JL, et al. Hydroxychloroquine use associated with improvement in lipid profiles in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:530–534. doi: 10.1002/acr.20393. This study demonstrated that hydroxychloroquine use in an incident cohort of RA patients was independently associated with a significant decrease in LDL, total cholesterol, LDL/HDL, and total cholesterol/HDL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCarey DW, McInnes IB, Madhok R, et al. Trial of Atorvastatin in Rheumatoid Arthritis (TARA): double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2015–2021. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32*.Sheng X, Murphy MJ, Macdonald TM, Wei L. Effectiveness of statins on total cholesterol and cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:32–40. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110318. This population-based cohort study demonstrated that statins reduce total cholesterol levels in patients with OA or RA, and are associated with reduced CVD events and mortality in RA and reduced mortality in OA in primary prevention. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33*.Semb AG, Holme I, Kvien TK, Pedersen TR. Intensive lipid lowering in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and previous myocardial infarction: an explorative analysis from the incremental decrease in endpoints through aggressive lipid lowering (IDEAL) trial. Rheumatology. 2011;50:324–329. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq295. This study was a randomized controlled trial in which patients with previous myocardial infarction were randomly assigned to receive atorvastatin or simvastatin daily and followed for nearly five years Patients with RA and previous MI had comparable lipid-lowering effects and similar rates of cardiovascular events as those without RA, although the RA patients had lower baseline cholesterol levels than patients without RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34*.De Vera MA, Choi H, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Statin discontinuation and risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1020–1024. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.142455. This population-based cohort study of RA patients with incident statin use demonstrated that RA patients who discontinue statin therapy have increased risk of acute myocardial infarction. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.TRACE-RA. http://www.dgoh.nhs.uk/tracera/default.aspxhttp://www.dgoh.nhs.uk/tracera/default.aspx. (11 December 2012, date last accessed)

- 36.Dessein PH, Joffe BI, Stanwix A, et al. The acute phase response does not fully predict the presence of insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in inflammatory arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:462–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maradit Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, et al. Cardiovascular death in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:722–732. doi: 10.1002/art.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naranjo A, Sokka T, Descalzo MA, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R30. doi: 10.1186/ar2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39*.Innala L, Moller B, Ljung L. Cardiovascular events in early RA are a result of inflammatory burden and traditional risk factors: a five year prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R131. doi: 10.1186/ar3442. This five-year, prospective study from Sweden demonstrated that new CVD events in very early RA was explained by traditional CVD risk factors and potentiated by high disease activity, whereas use of DMARDs decreased the risk. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Boyer JF, Gourraud PA, Cantagrel A, et al. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;78:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.07.016. This meta-analysis aimed to find differences in the prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors between RA patients and controls, with results showing that smoking, diabetes mellitus, and lower HDL cholesterol levels appear more prevalent in RA patients and may contribute to the increased CVD morbidity and mortality in RA patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panoulas VF, Douglas KMJ, Milionis HJ, et al. Prevalence and associations of hypertension and its control in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1477–1482. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aw TJ, Haas SJ, Liew D, Krum H. Meta-analysis of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and their effects on blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:490–496. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.5.IOI50013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson AG, Nguyen TV, Day RO. Do nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs affect blood pressure? A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:289–300. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-4-199408150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pope JE, Anderson JJ, Felson DT. A meta-analysis of the effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bang SY, Lee KH, Cho SK, et al. Smoking increases rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility in individuals carrying the HLA-DRB1 shared epitope, regardless of rheumatoid factor or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody status. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:369–377. doi: 10.1002/art.27272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baka Z, Buzàs E, Nagy G. Rheumatoid arthritis and smoking: putting the pieces together. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:238. doi: 10.1186/ar2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albano SA, Santana-Sahagun E, Weisman MH. Cigarette smoking and rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2001;31:146–159. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2001.27719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Escalante A, Haas RW, del Rincon I. Paradoxical effect of body mass index on survival in rheumatoid arthritis: role of comorbidity and systemic inflammation. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1624–1629. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Metsios GS, Koutedakis Y, et al. Obesity in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2011;50:450–462. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panoulas VF, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Metsios GS, et al. Association of interleukin-6 (IL-6)-174G/C gene polymorphism with cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the role of obesity and smoking. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Rifai N, Cook NR. Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: the Reynolds Risk Score. JAMA. 2007;297:611–619. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.6.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lemmey AB, Jones J, Maddison PJ. Rheumatoid cachexia: what is it and why is it important? J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2074. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pai JK, Pischon T, Ma J, et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2599–2610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Casas JP, Shah T, Hingorani AD, et al. C-reactive protein and coronary heart disease: a critical review. J Intern Med. 2008;264:295–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hein TW, Singh U, Vasquez-Vivar J, et al. Human C-reactive protein induces endothelial dysfunction and uncoupling of eNOS in vivo. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56*.Giles JT, Post WS, Blumenthal RS, et al. Longitudinal predictors of progression of carotid atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3216–3225. doi: 10.1002/art.30542. This prospective study of a 158-patient RA cohort followed for three years showed that higher swollen joint counts and higher C-reactive protein levels were associated with incident as well as progressive carotid plaque. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodson NJ, Symmons DP, Scott DG, et al. Baseline levels of C-reactive protein and prediction of death from cardiovascular disease in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis: a ten-year follow up study of a primary care-based inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2293–2299. doi: 10.1002/art.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58*.Hjeltnes G, Hollan I, Ferre O, et al. Anti-CCP and RF IgM: predictors of impaired endothelial function in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Scand J Rheumatol. 2011;40:422–427. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2011.585350. This prospective study of 53 RA patients evaluated the presence of anti-CCP antibodies and RF IgM and endothelial function in terms of the reactive hyperaemic index, showing that anti-CCP antibodies and RF IgM were related to impaired endothelial function independent of other cardiovascular risk factors in RA patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.López-Longo FJ, Oliver-Miñarro D, de la Torre I, et al. Association between anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies and ischemic heart disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:419–424. doi: 10.1002/art.24390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Juni P, Nartey L, Reichenbach S, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events and rofecoxib: cumulative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2004;364:2021–2029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17514-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, Redston M, Solomon SD, Kim K, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:873–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1092–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nussmeier NA, Whelton AA, Brown MT, et al. Complications of the COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1081–1089. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnsen SP, Larsson H, Tarone RE, et al. Risk of hospitalization for myocardial infarction among users of rofecoxib, celecoxib, and other NSAIDs – a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:978–984. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.9.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients taking cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: population based nested case-control analysis. BMJ. 2005;330:1366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7504.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chan AT, Manson JE, Albert CM, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and the risk of cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2006;113:1578–1587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Solomon DH, Glynn RJ, Rothman KJ, et al. Subgroup analyses to determine cardiovascular risk associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and coxibs in specific patient groups. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1097–1104. doi: 10.1002/art.23911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salpeter SR, Gregor P, Ormiston TM, et al. Meta-analysis: cardiovascular events associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 2006;119:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goodson NJ, Brookhart AM, Symmons DP, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use does not appear to be associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis: results from a primary care based inception cohort of patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:367–372. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ravindran V, Rachapalli S, Choy EH. Safety of medium to long term glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2009;48:807–811. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Loddenkemper K, Bohl N, Perka C, et al. Correlation of different bone markers with bone density in patients with rheumatic diseases on glucocorticoid therapy. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:331–336. doi: 10.1007/s00296-005-0608-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Panoulas VF, Douglas KM, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, et al. Long-term exposure to medium-dose glucocorticoid therapy associates with hypertension in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2008;47:72–75. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Munro R, Morrison E, McDonald AG, et al. Effect of disease modifying agents on the lipid profiles of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:374–377. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.6.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garcia-Gomez C, Nolla JM, Valverde J, et al. High HDL-cholesterol in women with rheumatoid arthritis on low-dose glucocorticoid therapy. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008;38:686–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.01994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Toms TE, Symmons DP, Kitas GD. Dyslipidaemia in rheumatoid arthritis: the role of inflammation, drugs, lifestyle and genetic factors. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2010;8:301–26. doi: 10.2174/157016110791112269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Toms T, Panoulas V, Douglas K, et al. Are lipid ratios less susceptible to change with systemic inflammation than individual lipid components in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Angiology. 2011;62:167–175. doi: 10.1177/0003319710373749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77*.Ruyssen-Witrand A, Fautrel B, Sarauxc A, et al. Cardiovascular risk induced by low-dose corticosteroids in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.02.040. This systemic literature review of RA patients taking low dose corticosteroids showed poor association between LDC exposure and CV risk factors, and a trend of increasing major CV events was identified. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choi HK, Hernan MA, Seeger JD, et al. Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:1173–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Halm VP, Nurmohamed MT, Twisk JW, et al. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are associated with a reduced risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a case control study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R151. doi: 10.1186/ar2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hochberg MC, Johnston SS, John AK. The incidence and prevalence of extra-articular and systemic manifestations in a cohort of newly-diagnosed patients with rheumatoid arthritis between 1999 and 2006. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:469–80. doi: 10.1185/030079908x261177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81*.Greenberg JD, Kremer JM, Curtis JR, et al. Tumour necrosis factor antagonist use and associated risk reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:576–82. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.129916. This cohort study compared the use of TNF antagonists, methotrexate and other non-biological DMARDs in RA patients, showing that TNF antagonist use was associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular events in patients with RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kremer JM. An analysis of risk factors and effect of treatment on the development of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:307. [Google Scholar]

- 83**.Micha R, Imamura F, Wyler von Ballmoos M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of methotrexate use and risk of cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1362–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.06.054. This systematic review and meta-analysis included cohort studies, case-control studies, and randomized trials if they reported associations between methotrexate and CVD risk Methotrexate use demonstrated a 21% lower risk for total CVD and an 18% lower risk for myocardial infarction without evidence for statistical between-study heterogeneity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Westlake SL, Colebatch AN, Baird J, et al. The effect of methotrexate on cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Rhematology. 2010;49:295–307. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ridker PM. Testing the inflammatory hypothesis of atherothrombosis: a scientific rationale for the cardiovascular inflammation reduction trial (CIRT) J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:332–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tracey D, Klareskog L, Sasso EH, et al. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist mechanism of action: a comprehensive review. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:244–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Levine B, Kalman J, Mayer L, et al. Elevated circulating levels of tumor necrosis factor in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:236–241. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007263230405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88*.Al-Aly Z, Pan H, Zeringue A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade, cardiovascular outcomes, and survival in rheumatoid arthritis. Transl Res. 2011;157:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2010.09.005. This cohort study demonstrated that use of TNF inhibitors in RA patients is not associated with an increased risk of atherosclerotic heart disease, congestive heart failure, or peripheral artery disease, but is associated with decreased risk of cerebrovascular disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89*.Ljung L, Simard JF, Jacobsson L, et al. Treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and the risk of acute coronary syndromes in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:42–52. doi: 10.1002/art.30654. In this cohort study of patients treated with TNF inhibitors within the first years of RA, treatment was not related to any statistically significant alteration in the risk of acute coronary syndrome. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jamnitski A, Visman IM, Peters MJ, et al. Beneficial effect of 1-year etanercept treatment on the lipid profile in responding patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the ETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1929–1933. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91*.Curtis JR, John A, Baser O. Dyslipidemia and changes in lipid profiles associated with rheumatoid arthritis and initiation of anti- TNF therapy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1282–1291. doi: 10.1002/acr.21693. This retrospective database study of patients with RA or osteoarthritis showed that RA patients were less likely to be tested for hyperlipidemia and had more favorable lipid profiles than patients with OA TNF inhibitor therapy modestly increased all lipid parameters in the RA group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pollono EN, Lopez-Olivo MA, Lopez JA, et al. A systematic review of the effect of TNF-alpha antagonists on lipid profiles in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:947–955. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93*.Van Sijl AM, Peters MJ, Knol DL, et al. The effect on TNF-alpha blocking therapy on lipid levels in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.04.003. This meta-analysis of RA patients following treatment with TNF inhibitor therapy showed that treatment with TNF inhibitors has a modest effect on total cholesterol and high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in RA patients with no significant overall effect on the atherogenic index. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94*.Daien CI, Duny Y, Barnetche T, et al. Effect of TNF inhibitors on lipid profile in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:862–868. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201148. This meta-analysis demonstrated that long-term treatment with TNF inhibitors in RA patients is associated with increased levels of high density lipoprotein and total cholesterol, whereas low density lipoprotein levels and the atherogenic index remain unchanged, suggesting that the presumed cardioprotective effects of TNF inhibitors in RA may not be explained by quantitative lipid changes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van Vollenhoven RF, Emery P, Bingham CO, III, et al. Long-term safety of patients receiving rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:558–567. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.van Vollenhoven RF, Emery P, Bingham CO, et al. Long-term safety of rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis: pooled analysis of patients in clinical trials with up to 9.5 years of treatment. Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology/Association of Rheumatology Health Professional; November 5–9 2011; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kerekes G, Soltesz P, Der H, et al. Effects of rituximab treatment on endothelial dysfunction, carotid atherosclerosis, and lipid profile in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;59:1821–1824. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Llorca J, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, et al. Short-term improvement of endothelial function in rituximab treated rheumatoid arthritis patients refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha blocker therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1821–1824. doi: 10.1002/art.24308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Welwyn Garden City, UK: Roche Registration Limited. RoActemra 20 mg/ml concentrate for solution for infusion [summary of product characteristics] 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Cocco G, et al. Adverse cardiovascular effects of antirheumatic drugs: implications for clinical practice and research. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:1543–1555. doi: 10.2174/138161212799504759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101*.Kawashiri SY, Kawakami A, Yamasaki S, et al. Effects of the anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab, on serum lipid levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:451–456. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1303-y. This case control study examined the effects of tocilizumab monotherapy versus conventional DMARD use on lipid metabolism in nineteen patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) After 3 months of treatment, serum levels of Apo A-1, Apo A-2, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein, and low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were significantly increased In the tocilizumab group, however all of the markers remained unchanged in the DMARD group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nishimoto N, Ito K, Takagi N. Safety and efficacy profiles of tocilizumab monotherapy in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: meta-analysis of six initial trials and five long term extensions. Md Rheumatol. 2010;20:222–32. doi: 10.1007/s10165-010-0279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103**.Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of tofacitinibmonotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:495–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109071. In this phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, 6-month study of patients with active RA, Tofacitinib treatment reduced signs and symptoms of RA but was associated with elevations in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104**.Liao KP, Solomon DH. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors, inflammation and cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2013;52:45–52. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes243. This review article demonstrates the challenges associated with risk stratification of patients with RA and shows that a gap in our knowledge exists given that most of the studies regarding traditional CVD risk factors stem from data collected as covariates for studies on CV disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chung CP, Oeser A, Avalos I, et al. Utility of the Framingham risk score to predict the presence of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R186. doi: 10.1186/ar2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106*.Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Roger VL, et al. Usefulness of risk scores to estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:420–424. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.044. This study demonstrated that the use of two commonly used CVD risk scoring systems–the Framingham and Reynolds risk scores–substantially underestimated CVD risk in patients with RA of both genders, especially in older ages and in patients with positive rheumatoid factor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]