Abstract

Aims

Impaired cardiac substrate metabolism plays an important role in heart failure (HF) pathogenesis. Since many of these metabolic changes occur at the transcriptional level of metabolic enzymes, it is possible that this loss of metabolic flexibility is permanent and thus contributes to worsening cardiac function and/or prevents the full regression of HF upon treatment. However, despite the importance of cardiac energetics in HF, it remains unclear whether these metabolic changes can be normalized. In the current study, we investigated whether a reversal of an elevated aortic afterload in mice with severe HF would result in the recovery of cardiac function, substrate metabolism, and transcriptional reprogramming as well as determined the temporal relationship of these changes.

Methods and results

Male C57Bl/6 mice were subjected to either Sham or transverse aortic constriction (TAC) surgery to induce HF. After HF development, mice with severe HF (% ejection fraction <30) underwent a second surgery to remove the aortic constriction (debanding, DB). Three weeks following DB, there was a near complete recovery of systolic and diastolic function, and gene expression of several markers for hypertrophy/HF were returned to values observed in healthy controls. Interestingly, pressure-overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and cardiac substrate metabolism were restored at 1-week post-DB, which preceded functional recovery.

Conclusions

The regression of severe HF is associated with early and dramatic improvements in cardiac energy metabolism and LVH normalization that precede restored cardiac function, suggesting that metabolic and structural improvements may be critical determinants for functional recovery.

Keywords: Cardiac hypertrophy, Heart failure regression, Metabolism, Remodelling

1. Introduction

Increases in aortic pressure resulting from conditions such as hypertension or valvular heart disease often induce compensatory structural remodelling of the left ventricle (LV), presenting as LV hypertrophy (LVH).1 These adaptive changes in the heart are necessary for the heart to normalize wall stress and to maintain cardiac output (CO).2 However, if the precipitating condition that increases afterload is not treated, the structural changes occurring within the heart may become maladaptive. This maladaptive remodelling of the LV can worsen over time and eventually transition from a compensated to decompensated hypertrophy and eventually to heart failure (HF).3,4

A hallmark of the transition from compensated to decompensated LVH is the genetic reprogramming of the metabolic pathways in the cardiomyocyte, which results in impaired cardiac energetics and subsequent impaired cardiac performance.5–8 Since many of these changes occur at the transcriptional level of the metabolic enzymes, it has been proposed that sustained loss of metabolic flexibility of the heart contributes to decreased mitochondrial flux and an energetically compromised heart.9,10 Although impaired cardiac energetics has been shown to be a major contributor to HF,11,12 whether or not this genetic reprogramming of the metabolic pathways can be reversed in established HF has not been extensively investigated. Therefore, to address this, we used a mouse model of severe HF to determine whether metabolic remodelling is reversible and whether regression of LVH or improved cardiac performance is preceded by improved cardiac energy metabolism. Overall, we propose that determining the potential reversibility of this previously assumed permanent change in cardiac metabolism has significant clinical implications for the treatment or management of patients with HF.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental animals

All protocols involving mice were approved by the University of Alberta Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conform with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institutes of Health (eighth edition; revised 2011). The University of Alberta adheres to the principles for biomedical research involving animals developed by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences and complies with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines. Male C57Bl/6 mice at 8 weeks of age were randomly assigned to the Sham (n = 9) or transverse aortic constriction (TAC, n = 48) group. At 3–4 weeks post-surgery, mice considered to be in severe HF [% ejection fraction (EF) <30] were then subjected to debanding (DB) surgery. An additional group of TAC mice served as controls without undergoing a DB surgery.

2.2. TAC surgery and DB

TAC surgery was performed as previously described.13 In brief, male 8-week-old mice were anaesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of a cocktail of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), intubated, and connected to a mouse ventilator (MiniVent, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). Following midline sternotomy, a double-blunted 27-gauge needle was tied encircling the aorta between the innominate and left common carotid arteries using a 6/0 silk suture. The needle was then removed, and chest and skin were sutured and closed. HF mice were then subjected to a second surgery re-entering through the original incision site. The TAC suture was carefully removed, and chest and skin were sutured closed (debanding, DB). Sham mice also underwent a second open-chest procedure.

2.3. Echocardiography

Mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane and in vivo cardiac function was assessed by transthoracic echocardiography using a Vevo 770 high-resolution imaging system equipped with a 30-MHz transducer (RMV-707B; VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada), as previously described.14 Pressure-overload was confirmed in all mice at 3-weeks after TAC by measuring trans-stenotic gradient by pulsed-wave Doppler flow. Full systolic and diastolic parameters were measured either at 3–4 weeks TAC or at 1 or 3-weeks following DB. Sham data were collected following two sham procedures.

2.4. Metabolic analysis in vivo

Total physical activity was measured using the Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS/Oxymax Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA) and was calculated by adding Z counts (rearing or jumping) to total counts associated with ambulatory movement and stereotypical rodent behaviour (grooming and scratching) as described previously.15 An Oxymax treadmill (Columbis Instruments) was used to determine running capacity in mice before or 1 or 3 weeks after DB. With a 10° incline, the belt speed was programmed to increase from 10 m/min by 1 m/min every minute, where VO2max was taken as peak VO2.

2.5. Histology

Masson's trichrome staining of paraffin-embedded left ventricular heart sections taken mid-papillary were visualized using a Leica DMLA microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a Retiga 1300i FAST 1394 CCD camera (OImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada), as described previously.16 Three representative images were taken from each sample and densitometric analysis was performed using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.6. Ex vivo heart perfusions

Mice were euthanized with an intraperitoneal injection of euthanyl (120 mg/kg body weight). Hearts were excised and perfused in working heart mode with Krebs–Henseleit buffer. Fatty acid and glucose oxidation rates were calculated based on the collection of myocardial 3H and 14CO2 production, respectively.13

2.7. Immunoblot analysis

Frozen heart tissue was homogenized according to the previously reported methods,16 and protein concentration was assayed using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (number 23 255; Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Protein (15–20 μg) was resolved by SDS–PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Densitometric analysis was performed using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) and corrected against Memcode protein stain as a loading control.

2.8. Quantitative real-time PCR

Cardiac mRNA expression was determined by real-time PCR using Taqman probes. Total RNA was extracted from heart tissue using the TRIzol RNA extraction method.17 RNA (1 µg) was subjected to reverse transcription to synthesize cDNA. Real-time PCR was performed by taking 5 µL of suitable cDNA dilutions from unknown, standard (brain cDNA) and 8 µL of Taqman master-mix (includes primers + probes) that were then loaded on white 384 Light cycler® 480 multiwell plates supplied from Roche. Gene expression of cardiac hypertrophy markers (anp, bnp, mhcβ, and mhcα), contractility (serca2a), fibrosis (col1a1), glucose metabolism (glut4 and pdk4), and fatty acid metabolism (ppara, mcd, pgc1a, and mcad) were analysed. Data are presented as mRNA molecules per nanogram total RNA relative to the control housekeeping gene (cyclophilin; see Supplementary material online for primers used in real-time PCR).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Comparisons between groups (Sham, TAC, and each respective DB group) were performed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test. A probability value of <0.05 is considered significant (see the Supplementary material online, Methods section for further description of methods).

3. Results

3.1. Removal of elevated aortic afterload improves survival and cardiac function in mice with pre-existing HF

Of the total of 44 male mice that successfully underwent TAC, 35 (79.5%) met criteria of %EF <30 by 3–4 weeks following surgery. At this time period, mice with established HF either remained as HF controls or underwent a second surgery to remove the aortic constriction (DB). Doppler echocardiography was used to confirm the presence of an elevated pressure gradient across the transverse aorta at 3-weeks following TAC (TAC: 53.5 ± 3.3 mmHg vs. Sham: 3.6 ± 0.4 mmHg) and subsequent normalization of this gradient following DB (8.4 ± 1.6 mmHg). We have previously shown that without intervention, mice with established HF have a 50% survival rate of ∼4 weeks,13 whereas mice with HF that underwent the DB procedure had no complications associated with HF even beyond 4 weeks following DB (data not shown).

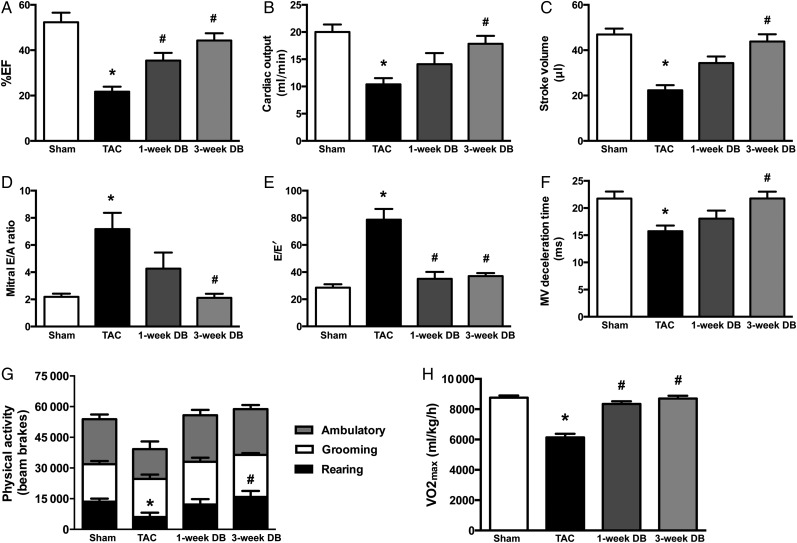

To determine whether prolonged survival in DB mice was due to restored cardiac function, mice were subjected to transthoracic echocardiography. At 3–4 weeks post-TAC, mice had a mean %EF of 21.73% compared to 52.33% for Sham controls (Figure 1A and Table 1). Moreover, mice subjected to TAC displayed additional impairments in systolic function, such as reductions in CO, stroke volume, and % fractional shortening (Figure 1A–C and Table 1), as well as diastolic dysfunction evident by an increase in mitral E/A and E/E′ ratios, with a shortened deceleration time (Figure 1D–F and Table 1). However, as early as 1-week following DB, all parameters of cardiac function showed improvement, with a near full recovery of systolic and diastolic function occurring by 3-weeks (Figure 1A–F and Table 1). To directly assess cardiac function in the absence of potential systemic or haemodynamic effects, mechanical function was also assessed ex vivo in the perfused working heart. Consistent with poor function in vivo, TAC hearts had reduced CO and aortic flow (58.9 and 44.7%, respectively) ex vivo, yet both of these parameters were fully restored to that of Sham-operated mice by 3-weeks post-DB (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Removal of elevated aortic afterload improves systolic (A–C) and diastolic (D–F) cardiac function and restores spontaneous physical activity and maximal exercise capacity in mice with heart failure. (A) Ejection fraction (%EF) (n = 8–9); (B) cardiac output (n = 7–9); (C) stroke volume (n = 7–9); (D) mitral E/A ratio (n = 5–9); (E) mitral E/E′ ratio (n = 5–9); (F) mitral valve (MV) deceleration time (n = 6–9). (G) Total 12-h rodent physical activity (divided into rearing, ambulatory, and grooming) as measured by metabolic cages (n = 4–10); (H) maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) during exercise (n = 4–9). *P < 0.05 vs. Sham; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC. TAC, transverse aortic constriction; DB, debanded.

Table 1.

Cardiac morphology and function in TAC and DB mice

| Sham | TAC | 1-week DB | 3-week DB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR, b.p.m. | 393.77 ± 19.78 | 464.30 ± 26.47 | 381.15 ± 14.86# | 388.30 ± 10.50# |

| Morphology | ||||

| Corr. LV mass, mg | 98.58 ± 5.11 | 149.42 ± 4.39* | 114.63 ± 5.65# | 122.45 ± 5.10*,# |

| IVS diastole, mm | 0.77 ± 0.02 | 0.98 ± 0.02* | 0.79 ± 0.02# | 0.82 ± 0.03# |

| IVS systole, mm | 1.05 ± 0.04 | 1.12 ± 0.03 | 0.99 ± 0.04 | 1.04 ± 0.03 |

| LVPW diastole, mm | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 0.98 ± 0.02* | 0.79 ± 0.02# | 0.82 ± 0.03# |

| LVPW systole, mm | 1.06 ± 0.04 | 1.12 ± 0.03 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 1.04 ± 0.03 |

| LVID diastole, mm | 4.25 ± 0.11 | 4.49 ± 0.09 | 4.53 ± 0.07 | 4.60 ± 0.11 |

| LVID systole, mm | 2.99 ± 0.13 | 3.94 ± 0.11* | 3.76 ± 0.10* | 3.55 ± 0.15 |

| LA diameter, mm | 1.93 ± 0.08 | 2.87 ± 0.08* | 2.33 ± 0.10# | 2.16 ± 0.12# |

| Systolic function | ||||

| EF, % | 52.33 ± 4.19 | 21.73 ± 2.22* | 35.41 ± 3.41*,# | 44.26 ± 3.22# |

| FS, % | 29.12 ± 1.79 | 10.40 ± 1.10* | 17.12 ± 1.92* | 22.06 ± 1.83# |

| LVEDV, µL | 81.49 ± 5.26 | 94.03 ± 4.86 | 94.23 ± 3.54 | 97.71 ± 5.88 |

| LVESV, µL | 35.71 ± 3.96 | 70.48 ± 4.19* | 61.08 ± 3.86* | 53.75 ± 5.96 |

| CO, mL/min | 20.01 ± 1.38 | 10.39 ± 1.14* | 14.09 ± 2.04 | 17.84 ± 1.47# |

| SV, µL | 46.92 ± 2.59 | 22.30 ± 2.25* | 34.34 ± 2.88*,# | 43.81 ± 3.24# |

| Diastolic function | ||||

| Mitral E/A ratio | 2.19 ± 0.24 | 7.17 ± 1.20* | 4.27 ± 1.18 | 2.12 ± 0.30# |

| Mitral E velocity, mm/s | 652.62 ± 35.63 | 824.02 ± 55.79 | 598.76 ± 64.72# | 625.84 ± 36.41# |

| Mitral A velocity, mm/s | 324.60 ± 36.10 | 136.35 ± 26.65 | 232.73 ± 77.39 | 313.17 ± 30.29 |

| E/E′ | 28.58 ± 2.46 | 78.64 ± 7.89* | 35.01 ± 5.11# | 37.01 ± 2.24# |

| Deceleration time, ms | 21.74 ± 1.29 | 15.75 ± 1.05* | 18.04 ± 1.50 | 21.77 ± 1.24# |

| IVRT, ms | 18.44 ± 1.36 | 14.42 ± 0.82 | 20.26 ± 1.01# | 19.17 ± 1.16 |

| IVCT, ms | 17.24 ± 1.34 | 17.98 ± 3.51 | 16.12 ± 1.69 | 14.64 ± 1.21 |

| ET, ms | 49.46 ± 2.22 | 43.63 ± 6.73 | 45.10 ± 1.87 | 48.74 ± 2.05 |

n= 7–9 shams; n= 4–10 TAC; n= 7–9 1-week DB; n= 7–9 3-week DB.

CO, cardiac output; DB, debanding; EF, ejection fraction; ET, ejection time; FS, fractional shortening; HR, heart rate; IVCT, isovolumic contraction time; IVRT, isovolumic relaxation time; IVS, interventricular septal wall; LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricle; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVID, left ventricular internal diameter; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; LVPW, left ventricular posterior wall thickness; SV, stroke volume; TAC, transverse aortic constriction.

*P < 0.05 vs. Sham or #P < 0.05 vs. TAC using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

Table 2.

Physical characteristics and ex vivo cardiac function in TAC and DB mice

| Sham | TAC | 1-week DB | 3-week DB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 27.10 ± 0.85 | 23.64 ± 0.47 | 24.61 ± 0.57 | 25.65 ± 0.69 |

| Atria weight, mg | 2.85 ± 0.21 | 6.94 ± 1.32* | 4.30 ± 0.45 | 2.64 ± 0.21# |

| Ex vivo function | ||||

| HR, b.p.m | 263.40 ± 11.80 | 216.71 ± 11.80 | 268.92 ± 12.00 | 270.36 ± 28.41 |

| PSP (mmHg) | 69.10 ± 0.91 | 59.00 ± 2.02* | 68.04 ± 1.53*,# | 71.24 ± 1.66*,# |

| HR × PSP (×10−3) (b.p.m. × mmHg) | 18.22 ± 0.90 | 12.81 ± 0.85* | 18.26 ± 0.70*,# | 19.18 ± 1.81*,# |

| CO, mL/min | 7.77 ± 0.70 | 4.58 ± 0.96 | 7.42 ± 0.77 | 9.49 ± 1.40# |

| Aortic flow, mL/min | 5.42 ± 0.81 | 2.42 ± 0.86 | 5.01 ± 0.75 | 7.26 ± 1.15# |

| Coronary flow, mL/min | 2.35 ± 0.20 | 2.16 ± 0.20 | 2.42 ± 0.05 | 2.23 ± 0.31 |

| Cardiac work, mL mmHg/min | 5.37 ± 0.47 | 2.73 ± 0.66 | 5.10 ± 0.60 | 8.79 ± 1.17*,# |

n = 5–9 shams; n = 5–7 TAC; n = 5–6 1-week DB; n = 4–5 3-week DB.

CO, cardiac output; DB, debanding; DP, developed pressure; HR, heart rate, PSP, peak systolic pressure.

*P < 0.05 vs. Sham or #P < 0.05 vs. TAC using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

3.2. Removal of elevated aortic afterload restores spontaneous physical activity and maximal exercise capacity in mice with pre-existing HF

Exercise intolerance is a hallmark of HF severity in patients with HF.18 Given that both systolic and diastolic dysfunction were returned to normal in hearts following DB of TAC mice, we investigated whether these improvements had any effect on daily physical activity or exercise capacity. Using the Oxymax laboratory animal monitoring system with x-, y-, and z-axis activity monitors, we determined that Sham and DB mice displayed higher levels of daily physical activity (evident by increased rearing) than did TAC mice (Figure 1G). Furthermore, when subjected to an exercise endurance test, DB mice showed fully restored exercise capacity, determined by restored maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) by 1-week post-DB (Figure 1H).

3.3. Removal of elevated aortic afterload causes a regression of LVH in mice with pre-existing HF

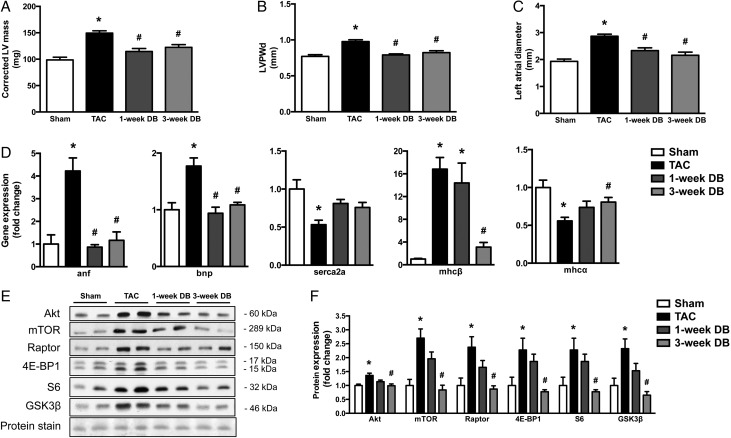

Morphological changes in response to pressure-overload include increased LVH, LV dilation, and increased left atrial (LA) diameter (Table 1). The presence of pressure-overload-induced LVH was evident in the TAC group compared to the Sham group by a 1.5-fold increase in LV mass and a 1.3-fold increase in wall thickness during diastole (Table 1). Surprisingly, DB mice demonstrate rapid regression of LVH, evidenced by significantly reduced LV mass, interventricular septal wall thickness, and LV posterior wall thickness during diastole as early as 1-week following DB (Figure 2A–C and Table 1), which preceded marked improvement in cardiac function. In addition, structural remodelling of the heart following TAC surgery resulted in an increase in LV internal diameter (LVID), LV volume, and enlarged LA, which were significantly reduced as early as 1-week post-DB. However, LVID and LV volume during diastole were not significantly reduced by DB (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Removal of elevated aortic afterload restores cardiac morphology and normalizes gene expression and molecular signalling events of LV hypertrophy in mice with heart failure. (A) LV mass; (B) LV posterior wall thickness during diastole (LVPWd) and (C) LA diameter (n = 5–9). (D) Gene expression of markers of pathological cardiac hypertrophy and HF (anp, bnp, mhcβ, mhcα, and serca2a) in ventricular tissue (n = 5–7). (E) Representative image and (F) densitometric analysis of immunoblot of proteins in the heart involved in protein synthesis (Akt, mTOR, Raptor, 4E-BP1, S6, and GSK3β) (n = 5–7). *P < 0.05 vs. Sham; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC. TAC, transverse aortic constriction; DB, debanded.

A hallmark of pathological hypertrophy is a shift in gene expression from the α-MHC to the β-MHC isoform.19–21 Therefore, in all groups of mice, we measured cardiac transcript levels of these as well as other molecular markers for LVH and HF, which are generally altered in hypertrophied/failing hearts (such as anf and bnp).22 In agreement with the regression of LVH, cardiac expression of these transcripts also returned to near-baseline values of Sham mice post-DB (Figure 2D). Furthermore, as reported previously,23 cardiac expression of serca2a, a Ca2+-ATPase that modulates cardiac contractility, was significantly reduced in TAC hearts, but returned to levels close to that of Sham-operated hearts by 3-weeks post-DB (Figure 2D).

In addition to changes in transcript levels of stress genes associated with HF and HF regression, previous reports have demonstrated TAC-induced activation of Akt and the mTOR signalling pathway.24 While expression of phosphorylated proteins did not appear to be altered in our HF mice (data not shown), total protein levels of Akt, mTOR, Raptor, 4E-BP1, S6, and GSK3β were significantly increased in response to pressure-overload, as previously described.25 More importantly, we observed normalized cardiac content of these regulators of protein synthesis following DB (Figure 2E and F), suggesting that some of the molecular signalling events that control hypertrophic growth have returned to baseline values and that the pro-hypertrophic molecular stimuli have also regressed.

3.4. Removal of elevated aortic afterload restores levels of markers of adverse cardiac remodelling without reversing cardiac fibrosis in mice with pre-existing HF

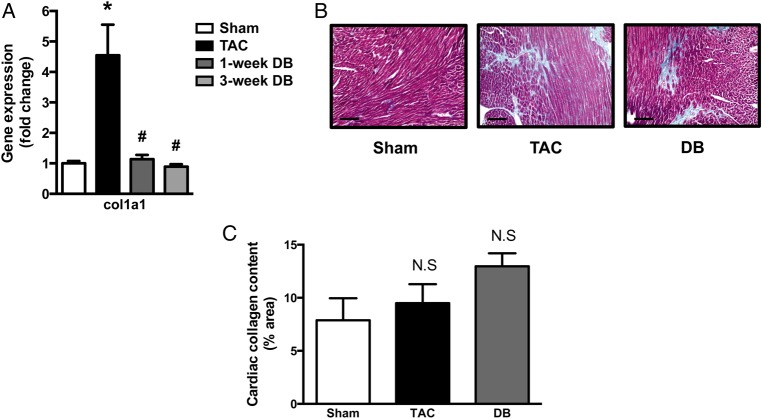

Since myocardial stiffness is a major result of pressure-overload due to worsening fibrosis, we investigated whether improved diastolic function in DB mice occurred as a result of reduced collagen deposition compared to TAC mice. The expression of collagen type 1 (col1a1), a gene involved in fibrotic remodelling, was increased five-fold in TAC hearts yet it was completely restored to that of Sham-operated mice by 1-week post-DB (Figure 3A). Surprisingly, however, despite significant recovery of diastolic function at 3-weeks following DB, Masson's trichrome staining showed a trend towards increased cardiac fibrosis in TAC mice that remained post-DB (Figure 3B and C). Taken together, these data suggest that while the potential for continued fibrosis and collagen deposition may be reduced, existing cardiac fibrosis is not degraded following DB.

Figure 3.

Removal of elevated aortic afterload restores the levels of markers of adverse cardiac remodelling without reversing cardiac fibrosis in mice with pre-existing heart failure. (A) Gene expression of the marker of cardiac fibrosis (col1α1) in ventricular tissue (n = 5–7); (B) representative images of left ventricular heart sections taken mid-papillary and stained with Masson’s trichrome at x 20 magnification; and (C) quantification of collagen staining in histological images expressed as % area (n = 3–4). Scale bars indicate 100 μm. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Sham; #P ≤ 0.05 vs. TAC. TAC, transverse aortic constriction; DB, debanded.

3.5. Removal of elevated aortic afterload normalizes genetic reprogramming and molecular signalling events of the metabolic pathways in mice with pre-existing HF

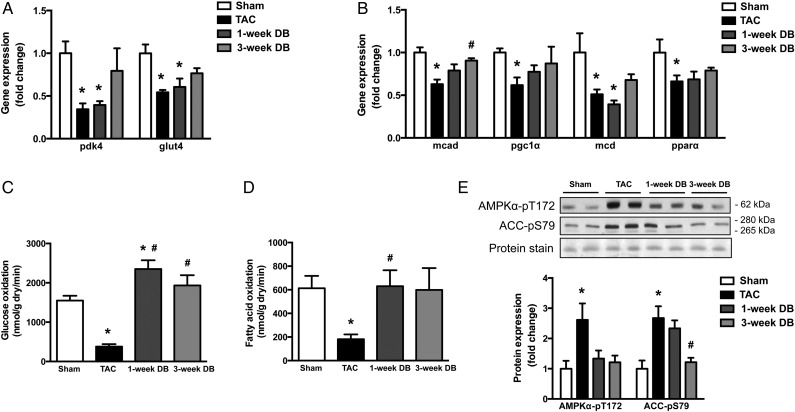

The healthy heart generates the majority of the necessary ATP primarily via the utilization of fatty acids and glucose.26 However, it has been shown that HF is associated with alterations at the transcriptional level of metabolic enzymes that contribute to impaired cardiac energetics.11,12 To determine whether these transcriptional changes are permanent, we measured the transcript levels of metabolic genes involved in both glucose and fatty acid metabolism in all hearts. Consistent with the previous work,27–31 numerous genes involved in the regulation of glucose (glut4 and pdk4) and fatty acid (mcad, pgc1α, mcd, and pparα) metabolism were significantly reduced in TAC hearts (Figure 4A and B). In most instances, unlike markers of cardiac hypertrophy (which were restored by 1–3 weeks following DB), gene expression of several regulators of both glucose and fatty acid transport and utilization (pdk4, glut4, pgc1α, mcd, and pparα) were not significantly different for mice following DB when compared to TAC controls. However, the expression of these markers also did not significantly differ from Sham-operated mice and transcript levels of mcad were significantly increased (Figure 4A and B), suggesting the potential for reversibility of the transcript levels of metabolic enzymes otherwise reduced by HF, beyond 3-weeks following DB.

Figure 4.

Removal of elevated aortic afterload normalizes transcript levels of metabolic enzymes and restores cardiac oxidative metabolism in mice with HF. Gene expression of proteins involved in (A) glucose (pdk4 and glut4) and (B) fatty acid (mcad, pgc1a, mcd, and ppara) uptake and metabolism (n = 5–7); and (C) glucose and (D) FA oxidation rates in hearts from ex vivo perfusions (n = 4–7). Representative images and densitometric analysis of (E) cardiac phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK; Thr 172) and phosphorylated acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC; Ser 79) in the heart as measured by immunoblot analysis (n = 5–7). *P < 0.05 vs. Sham; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC. TAC, transverse aortic constriction; DB, debanded.

3.6. Removal of elevated aortic afterload improves cardiac oxidative metabolism in mice with pre-existing HF

Although we did not observe normalization of transcript levels of metabolic enzymes normally reduced by HF, we directly measured ex vivo rates of glucose and fatty acid oxidation in all groups of hearts. Compared to Sham mice, mice with HF demonstrated significantly impaired myocardial glucose oxidation (Figure 4C) and fatty acid oxidation (Figure 4D) rates by 75 and 70%, respectively. This is consistent with numerous pervious reports that total myocardial oxidative metabolism is reduced in pressure-overload-induced HF.32,33

Contrary to our gene expression data, both glucose and fatty acid oxidation levels were restored to that of the Sham-operated group by 1-week post-DB, indicating a very early and remarkable recovery of cardiac energy metabolism following removal of the elevated aortic afterload. Consistent with this, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which is a metabolic stress kinase and thus an endogenous measure of cardiac myocardial energetic status,7,34–36 was activated in TAC hearts [indicated by phosphorylation of AMPK and its downstream target, acetyl-coA carboxylase (ACC)], but normalized post-DB (Figure 4E). Taken together, these data demonstrate that improved myocardial energetic status precedes cardiac functional recovery in TAC mice following DB.

4. Discussion

Here, we present data characterizing a mouse model of reversible HF using a DB surgery of a previously banded transverse aorta and have used this model to better understand the molecular and structural changes that occur in the regression of severe HF. This model is unique as the DB was performed in mice with severe HF (mean %EF of 21.73%) and the recovery period was studied for 3-weeks following DB. In addition to significant reductions in %EF, prior to DB, there was also a significant diastolic dysfunction, profound cardiac remodelling, and the mice exhibited severe exercise intolerance. Moreover, hearts from these mice demonstrated many of the hallmarks of HF such as increased transcript levels of cardiac stress markers (anf and bnp) as well as decreased expression of transcripts involved in HF (serca2a). Furthermore, molecular signalling pathways that mediate cellular growth in response to stress were also characteristically altered, as was the genetic reprogramming of the pathways controlling glucose and fatty acid oxidation, and an accompanying impairment of cardiac substrate metabolism. Using this model, we investigated whether removal of the elevated aortic afterload in mice with established severe HF would result in the recovery of cardiac function, substrate metabolism, and genetic reprogramming as well as determined the temporal relationship of these changes.

Since our model was designed to determine whether there was functional recovery following intervention after the establishment of severe HF, we first determined whether or not our DB procedure could reverse cardiac dysfunction. Interestingly, as early as 1-week post-DB, hearts from mice with previous HF started to show signs of improved systolic and diastolic function and a near full recovery of cardiac function was observed at 3-weeks post-DB. In fact, the majority of indices of cardiac function measured, such as CO, stroke volume, mitral E/A ratio, E/E′ ratio, and deceleration time, were returned to near-baseline levels observed in Sham mice. The noticeable exceptions to this were %FS and %EF, which were only recovered to 76 and 85%, respectively, of Sham controls at 3-weeks following DB. Although we cannot explain this delay in functional recovery compared to other parameters post-DB, it is likely that %FS and %EF would have returned to normal if the mice were allowed to recover for a longer period of time. Importantly, unlike previous studies where mice were debanded at a %EF of 39–53%,37–39 we provide evidence that mice with more severe HF are able to fully recover in response to pressure unloading. Importantly, this improved function is manifested in restored physical activity and exercise capacity in mice with pre-existing HF, suggesting that this major symptom of clinical HF also has the potential to be regressed.

As expected with almost complete recovery of heart function, we show that hearts undergo a dramatic beneficial remodelling that involves both concentric LVH regression and LA diameter normalization as early as 1-week following DB. While regression of LVH has previously been shown in models of compensated hypertrophy,38,40–42 ours is the first to demonstrate complete regression of LVH following severe HF. In addition to these morphological changes, the hearts also underwent profound changes in the expression of hypertrophy gene transcripts and the molecular signalling events that are associated with cardiac remodelling. For instance, a marked reversal in the expression of cardiac stress markers (such as anf and bnp) as early as 1-week following DB provides evidence that genetic reprogramming is not irreversible, even following severe HF. In addition, ours is the first study to demonstrate that protein expression of numerous molecules involved in regulating protein synthesis were altered in TAC hearts and normalized following DB. Particularly, the Akt/mTOR signalling pathway, which mediates cellular growth in response to stress,43 was normalized by 3-weeks following DB, suggesting that these hearts undergo reverse remodelling rapidly following relief of the pressure-overload.

Since myocardial stiffness is a major result of pressure-overload due, in part, to fibrosis, we investigated whether improved cardiac function in DB mice occurred as a result of reduced collagen deposition when compared to TAC mice. The expression of collagen type 1 (col1a1), a gene involved in fibrotic remodelling, was increased in TAC hearts and was completely restored to that of Sham-operated mice by 1-week post-DB. Interestingly, despite the normalization in col1a1 expression and the reduction in myocardial stiffness indicated by improved diastolic relaxation and function, there was a trend towards increased fibrosis in TAC hearts, which was not resolved following DB (Figure 3B and C). Thus, it appears that while remodelling and impaired function regress in our model of pressure unloading, residual cardiac fibrosis remains following pressure unloading, suggesting that reduced fibrosis is not responsible for this recovery.

Since we observed a near complete reversal of functional/structural remodelling as well as the reversal of the transcriptional changes observed in HF following DB, we assessed whether or not this was also the case with the significant transcriptional reprogramming of many of the proteins that control cardiac substrate metabolism that occurs in the hypertrophied/failing heart.44 Unlike the reversal of the hypertrophic and cardiac stress markers that occurred rapidly after DB, the altered expression of genes encoding for proteins involved in the regulation of glucose and fatty acid metabolism were either unchanged (pparα), not fully normalized (pdk4, glut4, pgc1α, and mcd), or did not normalize until 3-weeks post-DB (mcad). These data agree with the only partial reversal of depressed metabolic gene expression in the failing human heart upon implantation of a left ventricular assist device,45 suggesting that the impairment in cardiac energetics that occurs at the transcriptional level in HF is not fully recovered following unloading.

Since it is widely understood that a poor correlation exists between mRNA and protein expression levels,46–48 and cardiac energy metabolism is regulated at multiple levels including many post-translational modifications, we also measured phosphorylation of AMPK, a key regulator of cellular metabolism. Despite not observing dramatic changes in the expression of genes encoding for proteins involved in the regulation of glucose and fatty acid metabolism by 3-weeks following DB, activity of AMPK and its downstream target, ACC, were fully restored. Since activation of the AMPK signalling pathway may not be responsible for the rapid normalization of substrate utilization following DB, we speculate that post-translational modification of specific metabolic enzymes via AMPK-independent mechanisms is likely involved. However, we have not measured the activities of all enzymes involved in regulating glucose and fatty acid oxidation and thus cannot provide data to pinpoint the precise regulatory pathways involved.

While our data show that in response to pressure-overload the heart exhibits severely reduced glucose oxidation, this is not consistent with the work done by Riehle et al.49 that shows increased glucose oxidation and glycolysis rates in hearts subjected to TAC. These discrepancies may be accounted for by the stage of compensation and severity of HF induced in both our model and others who have demonstrated either no change or a decrease in both glucose and fatty acid oxidation in hearts subjected to aortic banding.32,33 In addition, several studies have demonstrated a switch from mitochondrial oxidative metabolism to increased rates of glycolysis in hypertrophied rodent hearts.7,50–52 Although glycolysis was not measured in the current study, we speculate, based on the reversal of cardiac function, regression of LVH, and normalization of fatty acid and glucose oxidation, that any potential changes in glycolysis in mice with HF would similarly be restored. Despite not measuring glycolysis in the present study, we did show that there was a striking and rapid normalization of cardiac oxidative metabolism (which is severely impaired in the failing heart13) as early as 1-week post-DB. While these data are consistent with normalized baseline cardiac substrate oxidation of dogs recovering from pacing-induced HF,53 this is the first account that fully restored fatty acid and glucose oxidation precedes recovery of cardiac function in the regression of severe HF. While the precise mechanisms responsible for this are unknown, it has been well established that increases in local ADP concentration at the myofilaments occur as a result of depressed energy metabolism in HF.54,55 In fact, Tian et al.56 have shown that a linear relationship exists between ADP and LVEDP; therefore, elevated ADP contributes to impaired relaxation. Taken together, these data support the concept that recovered myocardial energy reserve following HF contributes to restored diastolic function. Notwithstanding this, although it is likely that early recovery of energy production may drive the normalization of cardiac function, our data do not provide direct genetic or pharmacological evidence to definitively prove this conclusion. Although previous groups have studied metabolic remodelling in both humans and animal models of HF,45,53 our study is the first to address the temporal recovery of improved substrate oxidation in relationship to both morphological and functional improvements. In addition, while previous studies have assessed the recovery of HF in models exhibiting moderately reduced cardiac function,37–39 we have shown that even in a model of severe HF, the metabolic perturbations are reversible. However, in the current study, we examined the reversibility of impaired cardiac function and substrate metabolism under normal physiological conditions and whether or not debanded hearts respond to a second, delayed stress such as ischaemia or pressure-overload have yet to be determined.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study indicates that in severe HF, removal of the elevated aortic afterload enables complete restoration of myocardial substrate metabolism, LVH regression, and normalization of cardiac function. Importantly, LVH regression and normalization of cardiac energy metabolism occur prior to full functional recovery. Taken together, the data presented here show that impaired myocardial energy metabolism as a result of HF is not permanent and, in fact, suggest that early recovery of substrate utilization along with LVH regression may be critical determinants for functional recovery in the failing heart.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) to J.R.B.D. N.J.B. was supported by the Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship at the University of Alberta.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms Carrie-Lynn Soltys, Ms Amy Barr, and Mr Max Grenett for their technical assistance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Dorn GW II, Force T. Protein kinase cascades in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 2005;115:527–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naylor LH, George K, O'Driscoll G, Green DJ. The athlete's heart: a contemporary appraisal of the ‘morganroth hypothesis’. Sports Med 2008;38:69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorell BH. Transition from hypertrophy to failure. Circulation 1997;96:3824–3827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frey N, Olson EN. Cardiac hypertrophy: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Annu Rev Physiol 2003;65:45–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehman JJ, Kelly DP. Gene regulatory mechanisms governing energy metabolism during cardiac hypertrophic growth. Heart Fail Rev 2002;7:175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allard MF. Energy substrate metabolism in cardiac hypertrophy. Curr Hypertens Rep 2004;6:430–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nascimben L, Ingwall JS, Lorell BH, Pinz I, Schultz V, Tornheim K, Tian R. Mechanisms for increased glycolysis in the hypertrophied rat heart. Hypertension 2004;44:662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolwicz SC Jr, Tian R. Glucose metabolism and cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res 2011;90:194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neubauer S, Horn M, Cramer M, Harre K, Newell JB, Peters W, Pabst T, Ertl G, Hahn D, Ingwall JS, Kochsiek K. Myocardial phosphocreatine-to-ATP ratio is a predictor of mortality in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1997;96:2190–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taegtmeyer H. Genetics of energetics: transcriptional responses in cardiac metabolism. Ann Biomed Eng 2000;28:871–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharov VG, Todor AV, Silverman N, Goldstein S, Sabbah HN. Abnormal mitochondrial respiration in failed human myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2000;32:2361–2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paolisso G, Gambardella A, Galzerano D, D'Amore A, Rubino P, Verza M, Teasuro P, Varricchio M, D'Onofrio F. Total-body and myocardial substrate oxidation in congestive heart failure. Metabolism 1994;43:174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung MM, Das SK, Levasseur J, Byrne NJ, Fung D, Kim TT, Masson G, Boisvenue J, Soltys CL, Oudit GY, Dyck JR. Resveratrol treatment of mice with pressure-overload-induced heart failure improves diastolic function and cardiac energy metabolism. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung MM, Koonen DP, Soltys CL, Jacobs RL, Febbraio M, Dyck JR. Increased CD36 expression in middle-aged mice contributes to obesity-related cardiac hypertrophy in the absence of cardiac dysfunction. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89:459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koonen DP, Sung MM, Kao CK, Dolinsky VW, Koves TR, Ilkayeva O, Jacobs RL, Vance DE, Light PE, Muoio DM, Febbraio M, Dyck JR. Alterations in skeletal muscle fatty acid handling predisposes middle-aged mice to diet-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes 2010;59:1366–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kienesberger PC, Pulinilkunnil T, Sung MM, Nagendran J, Haemmerle G, Kershaw EE, Young ME, Light PE, Oudit GY, Zechner R, Dyck JR. Myocardial ATGl overexpression decreases the reliance on fatty acid oxidation and protects against pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction. Mol Cell Biol 2012;32:740–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong J, Basu R, Guo D, Chow FL, Byrns S, Schuster M, Loibner H, Wang XH, Penninger JM, Kassiri Z, Oudit GY. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 suppresses pathological hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis, and cardiac dysfunction. Circulation 2010;122:717–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conraads VM, Van Craenenbroeck EM, De Maeyer C, Van Berendoncks AM, Beckers PJ, Vrints CJ. Unraveling new mechanisms of exercise intolerance in chronic heart failure: role of exercise training. Heart Fail Rev 2013;18:65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiss E, Ball NA, Kranias EG, Walsh RA. Differential changes in cardiac phospholamban and sarcoplasmic reticular Ca(2+)-ATPase protein levels. Effects on Ca2+ transport and mechanics in compensated pressure-overload hypertrophy and congestive heart failure. Circ Res 1995;77:759–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowes BD, Minobe W, Abraham WT, Rizeq MN, Bohlmeyer TJ, Quaife RA, Roden RL, Dutcher DL, Robertson AD, Voelkel NF, Badesch DB, Groves BM, Gilbert EM, Bristow MR. Changes in gene expression in the intact human heart. Downregulation of alpha-myosin heavy chain in hypertrophied, failing ventricular myocardium. J Clin Invest 1997;100:2315–2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arai M, Matsui H, Periasamy M. Sarcoplasmic reticulum gene expression in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Circ Res 1994;74:555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kehat I, Molkentin JD. Molecular pathways underlying cardiac remodeling during pathophysiological stimulation. Circulation 2010;122:2727–2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li XM, Ma YT, Yang YN, Liu F, Chen BD, Han W, Zhang JF, Gao XM. Downregulation of survival signalling pathways and increased apoptosis in the transition of pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2009;36:1054–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu X, Lu Z, Fassett J, Zhang P, Hu X, Liu X, Kwak D, Li J, Zhu G, Tao Y, Hou M, Wang H, Guo H, Viollet B, McFalls EO, Bache RJ, Chen Y. Metformin protects against systolic overload-induced heart failure independent of AMP-activated protein kinase alpha2. Hypertension 2014;63:723–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shende P, Plaisance I, Morandi C, Pellieux C, Berthonneche C, Zorzato F, Krishnan J, Lerch R, Hall MN, Ruegg MA, Pedrazzini T, Brink M. Cardiac raptor ablation impairs adaptive hypertrophy, alters metabolic gene expression, and causes heart failure in mice. Circulation 2011;123:1073–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dolinsky VW, Dyck JR. Calorie restriction and resveratrol in cardiovascular health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1812:1477–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Razeghi P, Young ME, Alcorn JL, Moravec CS, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Metabolic gene expression in fetal and failing human heart. Circulation 2001;104:2923–2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Depre C, Shipley GL, Chen W, Han Q, Doenst T, Moore ML, Stepkowski S, Davies PJ, Taegtmeyer H. Unloaded heart in vivo replicates fetal gene expression of cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med 1998;4:1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arany Z, Novikov M, Chin S, Ma Y, Rosenzweig A, Spiegelman BM. Transverse aortic constriction leads to accelerated heart failure in mice lacking PPAR-gamma coactivator 1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:10086–10091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sack MN, Rader TA, Park S, Bastin J, McCune SA, Kelly DP. Fatty acid oxidation enzyme gene expression is downregulated in the failing heart. Circulation 1996;94:2837–2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barger PM, Brandt JM, Leone TC, Weinheimer CJ, Kelly DP. Deactivation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha during cardiac hypertrophic growth. J Clin Invest 2000;105:1723–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, Jaswal JS, Ussher JR, Sankaralingam S, Wagg C, Zaugg M, Lopaschuk GD. Cardiac insulin-resistance and decreased mitochondrial energy production precede the development of systolic heart failure after pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:1039–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhabyeyev P, Gandhi M, Mori J, Basu R, Kassiri Z, Clanachan A, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. Pressure-overload-induced heart failure induces a selective reduction in glucose oxidation at physiological afterload. Cardiovasc Res 2013;97:676–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagendran J, Waller TJ, Dyck JR. AMPK signalling and the control of substrate use in the heart. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013;366:180–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim TT, Dyck JR. Is AMPK the savior of the failing heart? Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015;26:40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian R, Musi N, D'Agostino J, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ. Increased adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activity in rat hearts with pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation 2001;104:1664–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen NM, Stansfield WE, Tang RH, Rojas M, Patterson C, Selzman CH. Recovery from decompensated heart failure is associated with a distinct, phase-dependent gene expression profile. J Surg Res 2012;178:72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X, Javan H, Li L, Szucsik A, Zhang R, Deng Y, Selzman CH. A modified murine model for the study of reverse cardiac remodelling. Exp Clin Cardiol 2013;18:e115–e117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bjornstad JL, Skrbic B, Sjaastad I, Bjornstad S, Christensen G, Tonnessen T. A mouse model of reverse cardiac remodelling following banding-debanding of the ascending aorta. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2012;205:92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang DK, Choi BY, Lee YH, Kim YG, Cho MC, Hong SE, Kim do H, Hajjar RJ, Park WJ. Gene profiling during regression of pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Physiol Genomics 2007;30:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stansfield WE, Charles PC, Tang RH, Rojas M, Bhati R, Moss NC, Patterson C, Selzman CH. Regression of pressure-induced left ventricular hypertrophy is characterized by a distinct gene expression profile. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:232–238, 238e231–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao XM, Kiriazis H, Moore XL, Feng XH, Sheppard K, Dart A, Du XJ. Regression of pressure overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005;288:H2702–H2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaanine AH, Hajjar RJ. AKT signalling in the failing heart. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:825–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai L, Leone TC, Keller MP, Martin OJ, Broman AT, Nigro J, Kapoor K, Koves TR, Stevens R, Ilkayeva OR, Vega RB, Attie AD, Muoio DM, Kelly DP. Energy metabolic reprogramming in the hypertrophied and early stage failing heart: a multisystems approach. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:1022–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Razeghi P, Young ME, Cockrill TC, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Downregulation of myocardial myocyte enhancer factor 2c and myocyte enhancer factor 2c-regulated gene expression in diabetic patients with nonischemic heart failure. Circulation 2002;106:407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vogel C, Marcotte EM. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet 2012;13:227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo Y, Xiao P, Lei S, Deng F, Xiao GG, Liu Y, Chen X, Li L, Wu S, Chen Y, Jiang H, Tan L, Xie J, Zhu X, Liang S, Deng H. How is mRNA expression predictive for protein expression? A correlation study on human circulating monocytes. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin 2008;40:426–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Sousa Abreu R, Penalva LO, Marcotte EM, Vogel C. Global signatures of protein and mRNA expression levels. Mol Biosyst 2009;5:1512–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riehle C, Wende AR, Zaha VG, Pires KM, Wayment B, Olsen C, Bugger H, Buchanan J, Wang X, Moreira AB, Doenst T, Medina-Gomez G, Litwin SE, Lelliott CJ, Vidal-Puig A, Abel ED. PGC-1β deficiency accelerates the transition to heart failure in pressure overload hypertrophy. Circ Res 2011;109:783–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leong HN, Ang B, Earnest A, Teoh C, Xu W, Leo YS. Investigational use of ribavirin in the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome, Singapore, 2003. Trop Med Int Health 2004;9:923–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lei B, Lionetti V, Young ME, Chandler MP, d'Agostino C, Kang E, Altarejos M, Matsuo K, Hintze TH, Stanley WC, Recchia FA. Paradoxical downregulation of the glucose oxidation pathway despite enhanced flux in severe heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2004;36:567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Razeghi P, Young ME, Ying J, Depre C, Uray IP, Kolesar J, Shipley GL, Moravec CS, Davies PJ, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Downregulation of metabolic gene expression in failing human heart before and after mechanical unloading. Cardiology 2002;97:203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qanud K, Mamdani M, Pepe M, Khairallah RJ, Gravel J, Lei B, Gupte SA, Sharov VG, Sabbah HN, Stanley WC, Recchia FA. Reverse changes in cardiac substrate oxidation in dogs recovering from heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008;295:H2098–H2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spindler M, Saupe KW, Christe ME, Sweeney HL, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Ingwall JS. Diastolic dysfunction and altered energetics in the alphaMHC403/+ mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 1998;101:1775–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tian R, Nascimben L, Ingwall JS, Lorell BH. Failure to maintain a low ADP concentration impairs diastolic function in hypertrophied rat hearts. Circulation 1997;96:1313–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tian R, Christe ME, Spindler M, Hopkins JC, Halow JM, Camacho SA, Ingwall JS. Role of MGADP in the development of diastolic dysfunction in the intact beating rat heart. J Clin Invest 1997;99:745–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]