Abstract

Importance

The neuroinflammatory hypothesis of major depressive disorder (MDD) is supported by several main findings: First, in humans and animals, activation of the immune system causes sickness behaviors that present during a major depressive episode (MDE) such as low mood, anhedonia, anorexia and weight loss. Second, peripheral markers of inflammation are frequently reported in MDD. Third, neuroinflammatory illnesses are associated with high rates of MDE. However, a fundamental limitation of the neuroinflammatory hypothesis is a paucity of evidence for brain inflammation during MDE.

To investigate whether microglial activation, an important aspect of neuroinflammation, is present during MDE, [18F]FEPPA positron emission tomography (PET) was applied to measure translocator protein total distribution volume (TSPO VT), an index of TSPO density. Translocator protein density is elevated in activated microglia.

Objective

To determine whether TSPO VT, is elevated in the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and insula in MDE secondary to MDD.

Design

Case-control study.

Setting

Tertiary care psychiatric hospital.

Participants

20 subjects with MDE secondary to MDD and 20 healthy controls, underwent an [18F]FEPPA PET scan. MDE subjects were medication-free for at least 6 weeks. All participants were otherwise healthy, and non-smoking.

Main Outcome Measure

TSPO VT was measured in the prefrontal cortex, ACC, and insula.

Results

In MDE, TSPO VT was significantly elevated in all brain regions examined (multivariate analysis of variance, F15,23=4.46, P=0.001).TSPO VT was increased, on average, by 30% in the prefrontal cortex, ACC and insula. In MDE, greater TSPO VT in the ACC correlated with greater depression severity (ACC: r=0.628, P=0.005).

Conclusions and Relevance

This finding provides the most compelling evidence to date for brain inflammation, and more specifically microglial activation, in MDE. This is important for improving treatment since it implies that therapeutics which reduce microglial activation should be promising for MDE. The correlation between higher ACC TSPO VT with severity of MDE is consistent with the concept that neuroinflammation in specific regions may contribute to sickness behaviors which overlap with the symptoms of MDE.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is highly prevalent and impactful, with active symptoms present in 4% of the adult population.1 Although MDD exhibits multiple molecular phenotypes2-5 there is accumulating evidence for a role of inflammation in generating symptoms of a major depressive episode (MDE). For example, induction of inflammation is associated with sad mood in humans6 and direct induction of the central immune system in rodents is associated with the sickness syndrome of anhedonia, weight loss and anorexia which overlap with the diagnostic criteria for MDE.7 Also in MDD, several markers of peripheral inflammation, including C-reactive protein, IL-6 and TNF-α are frequently increased.8 Interestingly, conditions which create neuroinflammation such as traumatic brain injury, systemic lupus erythematosus and multiple sclerosis are associated with prevalence rates of MDE as high as 50% suggesting a link between brain inflammation and mood symptoms.9

Presently, it is not clear whether brain inflammation occurs during a current MDE because most postmortem investigations of neuroinflammation sampled either MDD with a history of MDE or suicide victims with varied diagnoses. Within such studies, the samples of subjects with current MDE were small. Van Otterloo et al.10 reported no difference in density of activated microglia, in the white matter of the orbitofrontal region in 10 MDD subjects. Dean et al. sampled 10 MDD subjects and found significantly increased levels of the transmembrane form of TNF in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex but no difference in levels of this form of TNF in the anterior cingulate cortex and no difference in the soluble form of TNF in either region.11 Steiner et al. reported increased density of quinolinic acid positive cells, a marker influenced by microglial activation, in the anterior cingulate cortex of 7 MDE subjects.12 Microarray studies have had mixed results, with a positive finding by Shelton et al. of increased pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine mRNA in Brodmann Area 10 (BA10) in 14 MDD subjects,13 but several other microarray studies, most of which sampled adjacent regions of the prefrontal cortex, did not identify this result.14, 15 Amongst investigations in suicide victims one study reported greater HLA-DR staining, a marker of microglial activation, in the dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex16 and a second study reported greater levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β in BA10.17 Neither study of suicide found a relationship to MDD (or MDE) but there were less than 10 subjects with MDD in each study. The mixed results among postmortem investigations in MDD have been attributed to issues of variation in brain regions sampled, inclusion of early and late onset MDD, comorbidity of other psychiatric disorders and addiction and, with the exception of the microarray studies, small sample size, although it is plausible that lack of focus on sampling the state of MDE may be important for investigations of neuroinflammation.

To determine whether neuroinflammation occurs in MDE secondary to MDD, positron emission tomography may be applied to measure translocator protein (TSPO) binding in vivo. TSPO is an 18 kDa protein located on outer mitochondrial membranes in microglia and increased expression of TSPO occurs when microglia are activated during neuroinflammation.18 Recently, a new generation of positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracers were developed with superior quantification of TSPO binding and among these, [18F]FEPPA has excellent properties including high, selective affinity for TSPO19, increased binding during induced neuroinflammation,20 and a high ratio of specific binding relative to free and non-specific binding.21

To date, one neuroimaging study applied [11C]PBR28 PET to investigate TSPO levels in MDD, which was negative.22 This earlier study assessed whether TSPO levels were elevated in a sample of 10 MDD subjects (scanned once) under a variety of states (treated, untreated, symptomatic, partially symptomatic) hence, this study cannot be considered definitive for determining whether TSPO binding is elevated in MDE. Scores on the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale on the PET scan day ranged from 5 to 30, indicating that the severity ranged from almost asymptomatic to moderately symptomatic. Other issues which limit interpretation of this study include potential bias of ongoing antidepressant use, heterogeneity of combined sampling of early and late onset MDD, and incomplete information regarding a TSPO polymorphism (rs6971) known to influence binding of the new generation of TSPO PET radioligands, including [11C]PBR28 and [18F]FEPPA.23, 24

In the current study, [18F]FEPPA PET was applied to measure TSPO VT, an index of TSPO density, during MDE of MDD compared to healthy, age-matched controls. The main hypothesis was that TSPO VT would be elevated in MDE in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and insula. The PFC and ACC were chosen because of their role in mood regulation circuitry and affect dysregulation of MDD.25 The insula is a strong candidate for mediating some of the sickness behaviors in MDD as it is activated in response to an immune challenge26 and may participate in homeostatic regulation and interoceptive signaling in MDD.27, 28 The second hypothesis was that greater severity of symptom measures related to the sickness syndrome would be associated with greater elevation of TSPO VT in these regions.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty subjects with a current major depressive episode secondary to major depressive disorder (hereafter termed MDE subjects) and 20 age-matched healthy participants completed the study. Participants were recruited from the Toronto area community and a tertiary care psychiatric hospital (Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Canada) between May 1, 2010 and February 1, 2014. All were aged 18-70, non-smoking and in good physical health. None of the subjects had a history of autoimmune disease nor reported any recent illness. MDE subjects had early onset MDD (first MDE prior to age 45). Health or MDE was confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Healthy participants were age-matched within 4 years to depressed patients. Exclusion criteria for all subjects included: being pregnant, any herbal, drug or medication use within six weeks, except for oral contraceptives, and any history of neurological illness or injury. All participants underwent urine drug screening and women received a urine pregnancy test on the PET scan day. All subjects provided written informed consent after all procedures were fully explained. The protocol and informed consent forms were approved by the Center for Addiction and Mental Health Research Ethics Board, Toronto, Canada.

Participants with MDE were administered the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) at enrollment and on the PET scan day. For enrollment, a minimum score of 17 on the 17-item HDRS was required. All MDE subjects were medication-free for at least 6 weeks prior to the PET scan day (9 subjects had completed one or more previous anti-depressant trials). Other exclusion criteria included concurrent active axis I disorders including current alcohol or substance dependence, MDE with psychotic symptoms, bipolar disorder (type I or II) and borderline or antisocial personality disorder. Depression severity was measured as the total score on the 17-item HDRS which is also strongly correlated with sickness behaviors of low mood and anhedonia.29 Additional measures taken were body mass index (BMI) and levels of several peripheral inflammatory markers in serum (interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor α and C-reactive protein, see Supplementary Methods).

Image Acquisition and Analysis

Each participant underwent one [18F]FEPPA PET scan conducted at the Research Imaging Centre at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Canada. For this, intravenous [18F]FEPPA21 was administered as a bolus (mean ± SD, 180.5 ± 14.5 MBq or 4.88 ± 0.4 mCi). [18F]FEPPA was of high radiochemical purity (>96%) and high specific activity (119 ± 125 TBq/mmol). Manual and automatic (ABSS, Model #PBS-101 from Veenstra Instruments, Joure, The Netherlands) arterial blood samples were obtained to determine the ratio of radioactivity in whole blood to radioactivity in plasma, and the unmetabolized radioligand in plasma needed to create the input function for the kinetic analysis.30 The scan duration was 125 minutes following the injection of [18F]FEPPA. The PET images were obtained using 3D HRRT brain tomography (CPS/Siemens, Knoxville, TN, USA). All PET images were corrected for attenuation using a single photon point source, 137Cs (T1/2= 30.2 years, Eg = 662 keV) and were reconstructed by filtered back projection algorithm, with a HANN filter at Nyquist cutoff frequency.23

Each subject underwent a 2D axial proton density magnetic resonance scan acquired with a General Electric (Milwaukee, WI, USA) Signa 1.5 T magnetic resonance image scanner (slice thickness = 2mm, repetition time > 5 300 ms, echo time = 13 ms, flip angle = 90 degree, number of excitations = 2, acquisition matrix = 256 × 256, and field of view = 22cm). Regions of interest were automatically generated using the in-house software, ROMI, as previously described.31 Time activity curves were used to estimate TSPO VT using a two-tissue compartment model, which has been shown previously to be an optimal model to quantitate TSPO VT with [18F]FEPPA PET.30

DNA Extraction and Polymorphism Genotyping

The binding affinity of the second generation of radiotracers for TSPO, including [18F]FEPPA, is known to be affected by a co-dominantly expressed single nucleotide polymorphism (rs6971, C →T) in exon 4 of the TSPO gene.23, 24 High affinity binders (HAB, Ala147/Ala147) and mixed affinity binders (MAB, Ala147/Thr147) account for >90% of the population in North America.23 The polymorphism rs6971 was genotyped as described previously.23 One MDE subject was a low affinity binder (LB, Ala147/Thr147) and was not included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

For the primary hypothesis, PET data were analyzed by multivariate ANOVA with TSPO VT in PFC, ACC and insula as the dependent variables and diagnosis and genotype as fixed factors. Main effects were considered significant at the conventional P≤0.05. Effects in each region, analyzed by univariate ANOVA, were considered significant after Bonferroni correction (P≤0.017).

As a secondary analysis, a MANOVA including every brain region sampled (including all cortical and subcortical regions) was performed to assess the effect of diagnosis on TSPO VT. A partial correlation, controlling for rs6971 genotype, was used in a secondary analysis to quantitate the relationship between TSPO VT in the primary regions of interest and severity of symptoms of MDE measured by total HDRS score. HDRS score was missing in one MDE participant and was not included in this analysis. Partial correlations were considered significant at the Bonferroni corrected threshold of P≤0.008.

Results

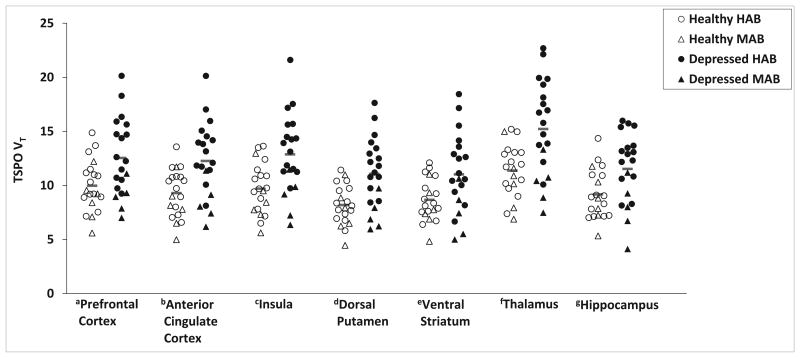

A global effect of diagnosis on TSPO VT was observed (Figure 1, Table 2). A MANOVA including all subregions of the prefrontal cortex as well as several other cortical and subcortical regions indicated a global brain effect of diagnosis with elevated TSPO VT in MDE compared to health (main effect of diagnosis, F15,23 = 4.46, P = 0.001). We also evaluated the regions selected in our hypothesis. Individuals in a MDE had significantly greater TSPO VT in prefrontal cortex (PFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and insula compared to healthy controls, after controlling for the effect of genotype (Figure 1. Effect of diagnosis, MANOVA, F3,35 = 4.73, P = 0.007. Effect of diagnosis, ANOVA by region: PFC, F1,37 = 8.07, P = 0.007; ACC, F1,37 = 12.24, P = 0.001; insula, F1,37 = 12.34, P = 0.001; magnitude increases 26%, 32%, 33%, respectively). In both groups, the effect of the rs6971 polymorphism was significant (MANOVA, effect of genotype: F3,35 = 4.5, P = 0.009) where HAB had higher TSPO VT compared to MAB. Scores on the HDRS indicated, on average, moderate to severe MDE (Table 1). Differences in TSPO VT between MDE and healthy subjects remained significant if age is applied as a covariate (see Supplemental Results). The frequency of MAB and HAB rs6971 genotype expression was not significantly different between healthy subjects and those with MDE.

Figure 1. Elevated translocator protein density (TSPO VT) during a major depressive episode (MDE) secondary to major depressive disorder (MDD).

TSPO VT was significantly greater in MDE of MDD (Depressed, N=20, 15 HAB, 5 MAB) compared to controls (Healthy, N=20, 14 HAB, 6 MAB): ANOVAs, aprefrontal cortex, F1,37 = 8.07, P = 0.007; banterior cingulate cortex, F1,37 = 12.24, P = 0.001; cinsula, F1,37 = 12.34, P = 0.001; ddorsal putamen, F1,37 =14.1, P=0.001; eventral striatum, F1,37 =6.9, P=0.013; fthalamus, F1,37 =13.6, P=0.001; ghippocampus, F1,37 =7.5, P=0.009. All second generation TSPO radioligands, such as [18F]FEPPA, show differential binding according to the SNP rs6971 of the TSPO gene resulting in high affinity binders (HAB) and mixed affinity binders (MAB). Red bars indicate means in each group.

Table 2. Analysis of Variance of Regional TSPO VT by Diagnosis and TSPO Genotypea.

| Depressed (n=20) |

Healthy (n=20) |

Diagnosis Effectb | Genotype Effectb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Region of Interest | HAB (n=15) | MAB (n=5) | Total | HAB (n=14) | MAB (n=6) | Total | F1,37 | P | F1,37 | P |

| MPFC | 13.6 (3.1) | 8.5 (2.0) | 12.3 (3.6) | 9.8 (2.1) | 8.3 (2.4) | 9.3 (2.2) | 11.4 | .002 | 11.2 | .002 |

| VLPFC | 14.9 (2.9) | 9.4 (1.7) | 13.5 (3.6) | 11.3 (2.4) | 9.5 (2.6) | 10.8 (2.5) | 9.1 | .005 | 13.5 | .001 |

| DLPFC | 13.6 (3.2) | 8.9 (1.3) | 12.4 (3.5) | 10.7 (2.3) | 8.8 (2.5) | 10.1 (2.5) | 6.5 | .015 | 11.6 | .002 |

| OFC | 14.4 (2.9) | 9.5 (2.7) | 13.2 (3.6) | 10.9 (2.4) | 9.6 (2.8) | 10.5 (2.5) | 7.8 | .008 | 9.4 | .004 |

| Frontal Pole | 13.3 (3.0) | 8.9 (2.0) | 12.2 (3.3) | 10.2 (2.1) | 8.3 (2.3) | 9.6 (2.3) | 9.1 | .005 | 11.8 | .002 |

| ACC | 13.5 (2.9) | 8.4 (2.0) | 12.3 (3.5) | 9.8 (2.0) | 8.0 (2.3) | 9.3 (2.2) | 12.2 | .001 | 14.2 | .001 |

| Insula | 14.2 (3.0) | 8.8 (2.1) | 12.9 (3.7) | 10.2 (2.2) | 8.6 (2.5) | 9.7 (2.3) | 12.3 | .001 | 12.6 | .001 |

| Temporal Cortex | 14.4 (2.8) | 8.7 (2.1) | 12.9 (3.6) | 10.9 (2.2) | 9.0 (2.5) | 10.3 (2.4) | 8.7 | .006 | 15.9 | .000 |

| Parietal Cortex | 15.0 (3.1) | 9.6 (2.0) | 13.7 (3.7) | 11.5 (2.2) | 9.6 (2.5) | 10.9 (2.4) | 8.9 | .005 | 13.8 | .001 |

| Occipital Cortex | 14.5 (3.0) | 8.4 (2.2) | 12.9 (3.9) | 11.0 (2.1) | 9.3 (2.7) | 10.5 (2.4) | 7.0 | .012 | 14.8 | .000 |

| Hippocampus | 12.8 (2.5) | 7.9 (2.7) | 11.5 (3.3) | 9.4 (2.3) | 8.6 (2.3) | 9.2 (2.3) | 7.5 | .009 | 9.4 | .004 |

| Thalamus | 16.9 (3.6) | 10.2 (2.2) | 15.2 (4.4) | 11.8 (2.2) | 10.4 (2.9) | 11.4 (2.4) | 13.6 | .001 | 12.5 | .001 |

| Dorsal Putamen | 12.3 (2.6) | 7.3 (1.5) | 11.1 (3.2) | 8.5 (1.6) | 7.5 (2.3) | 8.2 (1.8) | 14.1 | .001 | 12.4 | .001 |

| Dorsal Caudate | 10.9 (2.6) | 6.4 (1.8) | 9.8 (3.1) | 8.2 (1.9) | 6.7 (2.1) | 7.8 (2.0) | 6.7 | .013 | 13.4 | .001 |

| Ventral Striatum | 12.2 (3.2) | 7.4 (2.3) | 11.0 (3.7) | 9.0 (1.8) | 7.9 (2.1) | 8.7 (2.0) | 6.9 | .013 | 9.2 | .004 |

Values are expressed as mean (SD).

Main effect of univariate ANOVA. MPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; VLPFC, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; ACC, anterior cingulate cortex. HAB, high affinity binders and MAB, mixed affinity binders refer to the single nucleotide polymorphism rs6971 of the TSPO gene known to influence [18F]FEPPA binding. For a more detailed description of the subregions of the prefrontal cortex please refer to the supplemental section.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Study Participantsa.

| Characteristics | Depressed (n=20) | Healthy (n=20) |

|---|---|---|

| Female, No. (%) | 12 (67) | 11 (55) |

| Age, y | 34.0 (11.3) | 33.6 (12.8) |

| TSPO Genotypeb | 15 HAB, 5 MAB | 14 HAB, 6 MAB |

| BMI | 23.4 (5.4) | 24.8 (2.9) |

| HDRS Scorec | 20.0 (3.8) | na |

| Age of first MDE, y | 15.7 (5.2) | na |

| Previous MDEs, No. | 6 (3) | na |

| Previous AD Trial, No. (%) | 9 (45) | na |

| No Previous AD Trial, No. (%) | 11 (55) | na |

Values are expressed as mean (SD) except where indicated.

Single nucleotide polymorphism rs6971 of the TSPO gene known to influence [18F]FEPPA binding: HAB, high affinity binders; MAB, mixed affinity binders.

17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; scores derived on the day of scanning. Missing data in one subject.

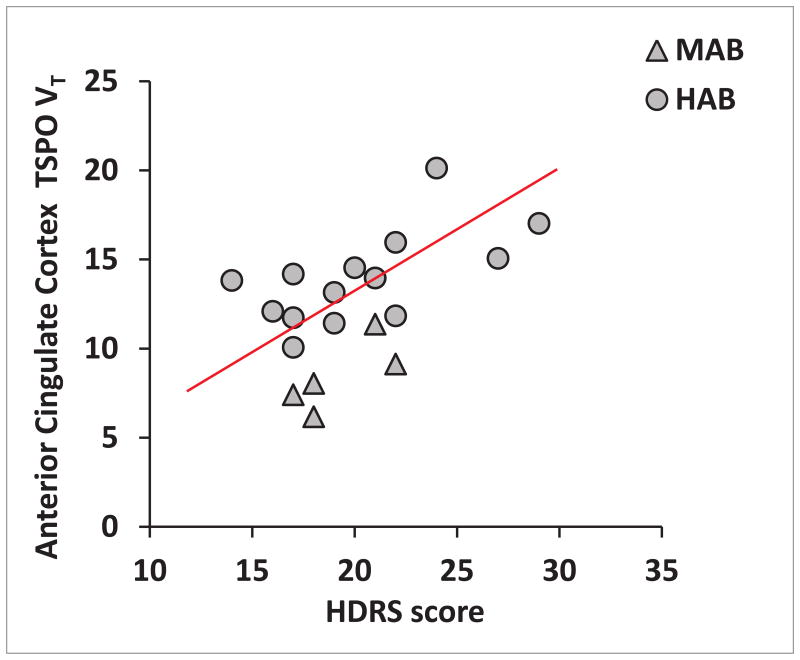

Total HDRS score, was positively correlated with TSPO VT in the ACC, after correcting for rs6971 genotype (r = 0.628, P = 0.005, Figure 2). Similar correlations were found in the insula and PFC but these did not survive Bonferroni correction (insula, r = 0.574, P = 0.013; PFC, r = 0.457, P = 0.057).

Figure 2. Relationship between regional translocator protein density (TSPO VT) and symptoms of current major depressive episode.

TSPO VT in the anterior cingulate cortex was positively related to scores on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), after correcting for rs6971 genotype (r=0.628, P=0.005). All second generation TSPO radioligands, such as [18F]FEPPA, show differential binding according to the SNP rs6971 of the TSPO gene resulting in high affinity binders (HAB) and mixed affinity binders (MAB).

In MDE subjects, but not healthy (see Supplementary Results), BMI was significantly, negatively correlated with TSPO VT in the insula, after correcting for rs6971 genotype (r = -0.605, P = 0.006). The relationship between BMI and TSPO VT was also present in ACC (r = -0.547, P = 0.015) and PFC (r = -0.488, P = 0.034) but neither survived Bonferroni correction. In MDE subjects, none of the serum markers of inflammation had a significant positive correlation with TSPO VT in the primary regions of interest (see Table 3).

Table 3. Lack of Positive Correlation Between Regional TSPO VT and Peripheral Inflammatory Markers in Major Depressive Episodes.

| Marker | Prefrontal Cortex | Anterior Cingulate Cortex | Insula |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| IL-1β | -0.35 (0.13)a | -0.39 (0.09) | -0.35 (0.14) |

| IL-6 | -0.20 (0.39) | -0.04 (0.88) | -0.09 (0.70) |

| TNFα | -0.29 (0.21) | -0.34 (0.14) | -0.36 (0.12) |

| CRP | -0.27 (0.25) | -0.16 (0.51) | -0.26 (0.27) |

|

| |||

| Correlations Controlling for rs6971 Genotype | |||

|

| |||

| IL-1β | -0.39 (0.10) | -0.45 (0.05) | -0.40 (0.09) |

| IL-6 | -0.29 (0.24) | -0.08 (0.75) | -0.15 (0.53) |

| TNFα | -0.33 (0.16) | -0.40 (0.09) | -0.44 (0.06) |

| CRP | -0.52 (0.02) | -0.40 (0.09) | -0.54 (0.02) |

|

| |||

| Correlations Controlling for Body Mass Index | |||

|

| |||

| IL-1β | -0.18 (0.46) | -0.21 (0.38) | -0.14 (0.56) |

| IL-6 | -0.12 (0.62) | 0.09 (0.71) | 0.03 (0.89) |

| TNFα | 0.18 (0.46) | 0.16 (0.52) | 0.18 (0.46) |

| CRP | -0.15 (0.54) | 0.01 (0.98) | -0.12 (0.63) |

|

| |||

| Correlations Controlling for Both rs6971 Genotype and Body Mass Index | |||

|

| |||

| IL-1β | -0.25 (0.31) | -0.31 (0.21) | -0.23 (0.36) |

| IL-6 | -0.22 (0.39) | 0.04 (0.87) | -0.04 (0.89) |

| TNFα | 0.05 (0.84) | 0.01 (0.97) | 0.03 (0.90) |

| CRP | -0.42 (0.08) | -0.25 (0.31) | -0.43 (0.07) |

Values represent the correlation coefficient (or partial correlation coefficient) followed by the two tailed, uncorrected p-value. Positive r values would reflect greater TSPO VT when a higher serum level of the peripheral marker is present. Body mass index (BMI) was included in two analyses since all of these serum markers are also secreted by adipocytes.

Discussion

This is the first study to detect microglial activation, as indicated by increased TSPO VT, in a substantial sample of MDE subjects. While the finding was prominent in the a priori regions of the PFC, ACC and insula, it was also present throughout all the regions assayed. Interestingly the highest levels of TSPO VT occurred in MDE subjects with the highest depression severity scores. These findings have important implications for the pathophysiology of MDE, identifying mechanisms contributing to symptom severity in MDE, and clinical targeting of treatment.

Since TSPO is upregulated in activated microglia, elevated TSPO VT implies that greater microglial activation, a potentially targetable process of neuroinflammation, is present during MDE. During activation, microglia transform from a monitoring role into a macrophage-like state, responding to infections or insults by phagocytosing pathogens and dying cells, and recruiting immune cells via cytokine secretion. However, active microglia during MDE may represent a maladaptive response. Identifying greater microglial activation in MDE suggests that selective therapeutic strategies such as stimulating microglial targets like CX3CR1 to promote a more quiescent state, suppressing the effects of cytokines in the central nervous system, or promoting a shift in microglial activity towards repair oriented functions by activating purinergic receptors may hold promise.32 Reducing microglial activation itself might also have therapeutic utility and consistent with this viewpoint, minocycline, a second generation tetracycline antibiotic known to reduce microglial activation and TSPO expression in rodents,33, 34 can attenuate depressive behaviors in rodents.35 The present study also suggests that the ability of such interventions to reduce microglial activation may be monitored by techniques such as [18F]FEPPA PET.

We found MDE was associated with elevated TSPO VT across all brain regions examined and regional TSPO VT was inter-correlated, although the relationships between TSPO VT with severity of MDE were most pronounced in the ACC. We propose that while global mechanisms may account for elevated TSPO VT in multiple brain regions in MDD, greater TSPO VT in specific regions and/or their associated circuitry may be influential for the expression of particular symptoms within this complex disorder. As with any association between symptoms and a central biomarker the correlation found between higher TSPO VT and greater HDRS score in the ACC, can be interpreted as an epiphenomenon secondary to a common origin or that one phenomenon predisposes to the other. We favor a causal mechanism of neuroinflammation contributing towards symptoms because induction of inflammation in humans is associated with depressed mood26, 36 and direct induction of central inflammation in rodents is associated with anhedonia.7 The function of this region in relation to symptoms of MDE is consistent with this interpretation: The ACC participates in regulating and processing negative emotional responses.25 In MDD, active MDE symptoms are associated with higher metabolic function in the ACC and direct stimulation of the subgenual ACC results in reduction of MDE symptoms.25 The negative relationship between TSPO VT and BMI may be consistent with anorexia following induction of central inflammation.7 The insula is important in this relationship as it integrates interoceptive and affective signaling, is involved in homeostatically driven responses to food cues.27 Future studies in preclinical models to induce microglial activation in combinations of regions that include the ACC and insula would be important to clarify the role of this pathology in relation to depressive behavior.

The lack of correlation between central and peripheral inflammatory markers is consistent with previous reports. Bromander et al., found no correlation between serum and cerebrospinal fluid TNF-α in neurosurgical patients.37 Similarly, dissociation between central and peripheral cytokines in preclinical data have been reported following peripheral38, 39 or central inflammatory stimuli.40 It has been proposed that peripheral cytokines cross the blood brain barrier in severe medical illness to induce neuroinflammation and symptoms of depression.41 However, our results suggest that central inflammation may be present during MDE even when peripheral inflammation is absent.

There are several limitations in this study, most of which are related to the interpretation of TSPO density and the use of PET imaging. To the best of our knowledge, the most supported explanation for greater TSPO binding with PET is microglial activation, although TSPO has other roles such as translocating cholesterol from outer to inner mitochondrial membranes for steroid hormone synthesis and participating in the mitochondrial permeability transition pore heterooligomer, which influences predisposition towards apoptosis.18 Hence, other explanations for elevated TSPO binding might be found in future study. Also, the resolution of the scanner does not allow for identification of the cell type involved. While elevated TSPO binding is most convincingly related to microglial activation,18 there is a minority in the field who suggest that it may also reflect astrocyte activation, at least under conditions, such as after exposure to high concentrations of cytokine neurotrophic factor.42

This is the first study to find a significant elevation of brain TSPO density in vivo, a marker of microglial activation and neuroinflammation, during MDE. Though MDD has often been associated with increased peripheral inflammatory markers, the current study provides the first important compelling evidence for a neuroinflammatory process of microglial activation during MDE in a substantial group of subjects unbiased by other psychiatric illnesses or recent medication. Correlations found between greater regional TSPO density in the anterior cingulate cortex and insula with severity of MDE and BMI, respectively, may be explained by microglial activation leading to abnormal function in these regions contributing to symptoms. Given the magnitude of difference in TSPO VT between the MDE and healthy subjects, replication should be possible in future studies, particularly if the MDE sample is focused on those with higher overall severity. Finally, the current results support further investigation of brain penetrant therapeutics that reduce microglial activation to treat MDE.

Acknowledgments

This research received project and salary support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (ES, Fellowship and JHM, Canada Research Chair), the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (ES, NARSAD Young Investigator Grant), and the National Institutes of Health (GR, Grant P30 GM103328), as well as infrastructure support from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI) and the Ontario Ministry for Research and Innovation. These funding sources did not participate in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. We thank research co-ordinators, Cynthia Xu, research assistant, Ian Fan, doctoral students Nathan Kolla and Andrea Tyrer, technicians Alvina Ng and Laura Nguyen, chemistry staff Jun Parkes, Armando Garcia, Winston Stableford and Min Wong, and engineers Terry Bell and Ted Harris- Brandts for their assistance with this project. Dr. Meyer had full access to all the data in the study and takes final responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This research was presented in part at the 2013 meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology and the 2014 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry. All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: JHM, AAW, SH, JLK, ES, and LM contributed to study design. JHM, SH, RM, PMR, and GR designed and validated region of interest analysis. JHM, ES, PVR, LM, PMR and IS recruited and assessed all participants, analyzed and interpreted data. JLK provided genotype data. ES and JHM drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical revisions and final approval of the submitted manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement: JHM, AAW and SH have received operating grant funds for other studies from Eli-Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lundbeck, and SK Life Sciences in the past 5 years. JHM has consulted to several of these companies as well as Takeda, Sepracor, Trius, Mylan and Teva. None of these companies participated in the design or execution of this study or in writing the manuscript. All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ustun TB, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S, Mathers C, Murray CJ. Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:386–392. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dwivedi Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: role in depression and suicide. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:433–449. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s5700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacQueen G, Frodl T. The hippocampus in major depression: evidence for the convergence of the bench and bedside in psychiatric research? Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(3):252–264. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer JH. Neuroimaging markers of cellular function in major depressive disorder: implications for therapeutics, personalized medicine, and prevention. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(2):201–214. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajkowska G, Miguel-Hidalgo JJ. Gliogenesis and glial pathology in depression. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2007;6(3):219–233. doi: 10.2174/187152707780619326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reichenberg A, Yirmiya R, Schuld A, Kraus T, Haack M, Morag A, Pollmacher T. Cytokine-associated emotional and cognitive disturbances in humans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(5):445–452. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu X, Zunich SM, O'Connor JC, Kavelaars A, Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Central administration of lipopolysaccharide induces depressive-like behavior in vivo and activates brain indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase in murine organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:43. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2006;27(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maes M, Kubera M, Obuchowiczwa E, Goehler L, Brzeszcz J. Depression's multiple comorbidities explained by (neuro)inflammatory and oxidative & nitrosative stress pathways. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2011;32(1):7–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Otterloo ES, Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Stockmeier C, Rajkowska G. patients Paper presented at: Society for Neuroscience. Washington, DC: 2005. Microglia immunoreactivity is unchanged in the white matter of orbitofrontal cortex in elderly depressed. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean B, Tawadros N, Scarr E, Gibbons AS. Regionally-specific changes in levels of tumour necrosis factor in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex obtained postmortem from subjects with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010;120(1-3):245–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner J, Walter M, Gos T, Guillemin GJ, Bernstein HG, Sarnyai Z, Mawrin C, Brisch R, Bielau H, Meyer zu Schwabedissen L, Bogerts B, Myint AM. Severe depression is associated with increased microglial quinolinic acid in subregions of the anterior cingulate gyrus: evidence for an immune-modulated glutamatergic neurotransmission? J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:94. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shelton RC, Claiborne J, Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz M, Reddy R, Aschner M, Lewis DA, Mirnics K. Altered expression of genes involved in inflammation and apoptosis in frontal cortex in major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(7):751–762. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sequeira A, Gwadry FG, Ffrench-Mullen JM, Canetti L, Gingras Y, Casero RA, Jr, Rouleau G, Benkelfat C, Turecki G. Implication of SSAT by gene expression and genetic variation in suicide and major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(1):35–48. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sibille E, Arango V, Galfalvy HC, Pavlidis P, Erraji-Benchekroun L, Ellis SP, John Mann J. Gene expression profiling of depression and suicide in human prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(2):351–361. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steiner J, Bielau H, Brisch R, Danos P, Ullrich O, Mawrin C, Bernstein HG, Bogerts B. Immunological aspects in the neurobiology of suicide: elevated microglial density in schizophrenia and depression is associated with suicide. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(2):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandey GN, Rizavi HS, Ren X, Fareed J, Hoppensteadt DA, Roberts RC, Conley RR, Dwivedi Y. Proinflammatory cytokines in the prefrontal cortex of teenage suicide victims. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(1):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rupprecht R, Papadopoulos V, Rammes G, Baghai TC, Fan J, Akula N, Groyer G, Adams D, Schumacher M. Translocator protein (18 kDa) (TSPO) as a therapeutic target for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(12):971–988. doi: 10.1038/nrd3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennacef I, Salinas C, Horvath G, Gunn R, Bonasera T, Wilson A, Gee A, Laruelle M. Comparison of [11C]PBR28 and [18F]FEPPA as CNS peripheral benzodiazepine receptor PET ligands in the pig. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(Supplement 1):81P. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kudo G, Toyama H, Hatano K, Suzuki H, Wilson AA, Ichise M, Ito F, Kato T, Katada K, Sawada M, Ito K. In-vivo imaging of microglial activation using a novel peripheral benzodiazepine receptor ligand, 18F-FEPPA and animal PET following 6-OHDA injury of the rat striatum; A comparison with 11C-PK11195. NeuroImage. 2008;41(Supplement 2):T94–T94. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson AA, Garcia A, Parkes J, McCormick P, Stephenson KA, Houle S, Vasdev N. Radiosynthesis and initial evaluation of [18F]-FEPPA for PET imaging of peripheral benzodiazepine receptors. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35(3):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannestad J, DellaGioia N, Gallezot JD, Lim K, Nabulsi N, Esterlis I, Pittman B, Lee JY, O'Connor KC, Pelletier D, Carson RE. The neuroinflammation marker translocator protein is not elevated in individuals with mild-to-moderate depression: a [(11)C]PBR28 PET study. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;33:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizrahi R, Rusjan PM, Kennedy J, Pollock B, Mulsant B, Suridjan I, De Luca V, Wilson AA, Houle S. Translocator protein (18 kDa) polymorphism (rs6971) explains in-vivo brain binding affinity of the PET radioligand [(18)F]-FEPPA. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(6):968–972. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owen DR, Yeo AJ, Gunn RN, Song K, Wadsworth G, Lewis A, Rhodes C, Pulford DJ, Bennacef I, Parker CA, StJean PL, Cardon LR, Mooser VE, Matthews PM, Rabiner EA, Rubio JP. An 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) polymorphism explains differences in binding affinity of the PET radioligand PBR28. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(1):1–5. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ressler KJ, Mayberg HS. Targeting abnormal neural circuits in mood and anxiety disorders: from the laboratory to the clinic. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(9):1116–1124. doi: 10.1038/nn1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannestad J, Subramanyam K, Dellagioia N, Planeta-Wilson B, Weinzimmer D, Pittman B, Carson RE. Glucose metabolism in the insula and cingulate is affected by systemic inflammation in humans. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(4):601–607. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.097014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avery JA, Drevets WC, Moseman SE, Bodurka J, Barcalow JC, Simmons WK. Major Depressive Disorder Is Associated with Abnormal Interoceptive Activity and Functional Connectivity in the Insula. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76(3):258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmons WK, Rapuano KM, Kallman SJ, Ingeholm JE, Miller B, Gotts SJ, Avery JA, Hall KD, Martin A. Category-specific integration of homeostatic signals in caudal but not rostral human insula. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(11):1551–1552. doi: 10.1038/nn.3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vrieze E, Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Hermans D, Pizzagalli DA, Sienaert P, Hompes T, de Boer P, Schmidt M, Claes S. Dimensions in major depressive disorder and their relevance for treatment outcome. J Affect Disord. 2014;155:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rusjan P, Wilson AA, Bloomfield PM, Vitcu I, Meyer J, Houle S, Mizrahi R. Quantification of translocator protein (18kDa) in the human brain with PET and a novel radioligand, [18F]-FEPPA. JCBFM. 2010;31(8):1807–1816. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiuccariello L, Houle S, Miler L, Cooke RG, Rusjan PM, Rajkowska G, Levitan RD, Kish SJ, Kolla NJ, Ou X, Wilson AA, Meyer JH. Elevated monoamine oxidase a binding during major depressive episodes is associated with greater severity and reversed neurovegetative symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(4):973–980. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kierdorf K, Prinz M. Factors regulating microglia activation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:44. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin A, Boisgard R, Kassiou M, Dolle F, Tavitian B. Reduced PBR/TSPO expression after minocycline treatment in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia: a PET study using [(18)F]DPA-714. Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;13(1):10–15. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0324-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He Y, Appel S, Le W. Minocycline inhibits microglial activation and protects nigral cells after 6-hydroxydopamine injection into mouse striatum. Brain Res. 2001;909(1-2):187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02681-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henry CJ, Huang Y, Wynne A, Hanke M, Himler J, Bailey MT, Sheridan JF, Godbout JP. Minocycline attenuates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation, sickness behavior, and anhedonia. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrison NA, Brydon L, Walker C, Gray MA, Steptoe A, Critchley HD. Inflammation causes mood changes through alterations in subgenual cingulate activity and mesolimbic connectivity. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(5):407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bromander S, Anckarsater R, Kristiansson M, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Anckarsater H, Wass CE. Changes in serum and cerebrospinal fluid cytokines in response to non-neurological surgery: an observational study. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:242. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bay-Richter C, Janelidze S, Hallberg L, Brundin L. Changes in behaviour and cytokine expression upon a peripheral immune challenge. Behav Brain Res. 2011;222(1):193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin L, Wu X, Block ML, Liu Y, Breese GR, Hong JS, Knapp DJ, Crews FT. Systemic LPS causes chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration. Glia. 2007;55(5):453–462. doi: 10.1002/glia.20467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Simoni MG, Terreni L, Chiesa R, Mangiarotti F, Forloni GL. Interferon-gamma potentiates interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha but not IL-1beta induced by endotoxin in the brain. Endocrinology. 1997;138(12):5220–5226. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.12.5616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dantzer R, O'Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lavisse S, Guillermier M, Herard AS, Petit F, Delahaye M, Van Camp N, Ben Haim L, Lebon V, Remy P, Dolle F, Delzescaux T, Bonvento G, Hantraye P, Escartin C. Reactive astrocytes overexpress TSPO and are detected by TSPO positron emission tomography imaging. J Neurosci. 2012;32(32):10809–10818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1487-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]