Abstract

Purpose

It is well established that empirically supported treatments reduce depressive symptoms for the majority of adolescents; however, it is not yet known whether these interventions lead to sustained improvements in global functioning. The goal of this study is to assess the clinical characteristics and trajectories of long-term psychosocial functioning among emerging adults who have experienced adolescent-onset MDD.

Methods

Global functioning was assessed using the Clinical Global Assessment Scale for Children (CGAS; participants ≤18 years old), the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; participants ≥ 19 years old) and the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Adolescents (HONOSCA) among 196 adolescents who elected to complete 3.5 years of naturalistic follow-up subsequent to their participation in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). TADS examined the efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), fluoxetine (FLX), and the combination of CBT and FLX (COMB) over 36 weeks. Mixed-effects regression models were used to identify trajectories and clinical predictors of functioning over the naturalistic follow-up.

Results

Global functioning and achievement of developmental milestones (college, employment) improved over the course of follow-up for the majority of adolescents. Depressive relapse, initial randomization to the placebo (PBO) group, and the presence of multiple psychiatric comorbidities conferred risk for relatively poorer functioning.

Conclusions

Functioning generally improves among the majority of adolescents who have received empirically supported treatments. However, the presence of recurrent MDD and multiple psychiatric comorbidities is associated with poorer functioning trajectories, offering targets for maintenance treatment or secondary prevention.

Keywords: Intervention Studies, longitudinal studies, depression

Introduction

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) with adolescent-onset leads to impaired functioning(1, 2). Functional impairment refers to limitations deriving from illness in social, occupational, and other important areas of daily life. It is differentiated from core psychological symptoms in that it represents how symptoms affect an individual's ability to meet or adaptively respond to various problems in living. Functional impairment may be particularly disruptive during the transition from adolescence to adulthood, which is a critical period for attaining key developmental milestones including attending college, obtaining employment, and learning to live independently(3). During this time questions of identity become paramount, catalyzed by the onset of puberty(4), increasing complexity of parental(5), peer and romantic relationships(6, 7), and rising expectations of independent functioning(8). Viewed through this lens, transition from adolescence to young adulthood is a demanding developmental stage for even the well-adjusted adolescent. Limited research has examined how depression during this critical window affects how adolescents are able to meet these challenges(9).

Tragically, treatments that reduce depressive symptoms do not consistently improve functional impairment. Several trials of SSRIs(10-12) either failed to improve functioning or did not report on these outcomes. One study of CBT among youth with MDD(13), found no difference in global functioning compared to other psychotherapies, despite the superiority of CBT for depressive symptoms. In The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS), only one-third of adolescents achieved normalized functioning (i.e., “non-impaired” according to the Children's Global Assessment Scale; CGAS) after 12 weeks(14) and functioning outcomes were not evaluated at longer follow-up intervals. Improved functioning may simply take more time, as was evident in a study of antidepressants for adults with chronic MDD(15). In addition, adolescence is a period of development characterized by naturalistic fluctuations in mood and functioning, which might obscure gains associated with treatment. However, opportunities to examine long-term functioning during the transition to adulthood have been limited to date.

Another explanation for the gap between symptom improvement and functioning is that one global rating is typically used to assess functioning rather than individual domains (i.e., family, peer, occupational, academic), making it difficult to understand functioning trajectories across development. It remains unknown whether global, domain-specific, or combined ratings of functioning best capture true impairment (16). As a result, the two main diagnostic classification systems (The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and International Classification of Diseases) use different functioning rating systems. However, no studies to our knowledge have evaluated the course and development of functioning using both approaches. One measure, The Health of the Nation Outcome Scale for Children and Adolescents (HoNOSCA;(17)) captures 13 specific domains of functioning. Unfortunately, only two studies examining adolescent depression over extended follow-up have used the HoNOSCA. One found no differences between combination treatment (SSRI and CBT) relative to SSRI alone(18). Another found no differences between group therapy and routine care on rate of HoNOSCA change(19).

The complex presentation of adolescent depression may also relate to challenges achieving functional milestones. Adolescents with past depression are at high risk for relapse(20) and experience disproportionately high rates of comorbid disorders including anxiety(21), disruptive behaviors(22), and substance abuse(23). Psychiatric co-morbidity during adolescence is associated with poor treatment prognosis(24), greater risk of suicide(25), and persistence of psychopathology during adulthood (26). Despite understanding of the clinical sequelae of psychiatric co-morbidity, limited data exists examining how co-morbidity affects specific domains of functioning. This may offer insight into potential targets for secondary, preventative, or maintenance interventions.

We examine functional outcomes in The Survey of Outcomes Following Treatment for Adolescent Depression (SOFTAD); an open, naturalistic follow-up lasting 3.5 years of adolescents who completed TADS(20). SOFTAD is the largest follow-up of depressed adolescents who received treatment(20). We examine trajectories of global functioning, as well as clinical attributes, including comorbidity profiles, which may confer risk for poorer functioning and interference with developmental milestones. We hypothesized that 1) functioning following treatment would be maintained among teens who received an active treatment; and 2) MDD relapse and comorbid psychiatric disorders would be associated with poorer functioning. As SOFTAD was not originally designed to examine these questions, the hypotheses are exploratory in the hopes of guiding future research on this understudied topic.

Methods

Study Design

The design and characteristics of TADS(27) and SOFTAD(20) have been described. Adolescents in TADS (N=439) were randomized to FLX, CBT, COMB, or PBO for 12 weeks of acute treatment. Treatment responders to the three treatments (FLX, CBT, COMB) received six weeks of continuation treatment plus 18 weeks of maintenance treatment. “Non-responders”(27) were referred to community treatment, offered 12 weeks of active treatment of their choice after the acute treatment phase, and then additional 12 weeks of uncontrolled continued care. Approximately 88% of PBO participants chose treatment with a TADS active treatment and approximately 80% continued with uncontrolled continued care after that(28). After 36 weeks, all adolescents were followed naturalistically (i.e. no research intervention or restrictions on outside treatment) for one year. SOFTAD was an extended naturalistic follow-up for an additional 3.5 years.

Participants

All TADS participants could enroll in SOFTAD. Forty-six percent (n=196) of TADS participants enrolled. Recruitment occurred at 12 of the 13 original sites. Demographic and clinical characteristics of SOFTAD participants have been described in relation to the TADS sample; specifically demographic characteristics at TADS baseline of SOFTAD participants were compared to participants who only did TADS(20). The SOFTAD sample was younger, included fewer minority adolescents, was more likely to be experiencing their initial depressive episode, and had fewer comorbidities at TADS baseline.

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the sites respective institutional review boards. SOFTAD involved seven assessments every six-months after the final TADS visit. Five assessments were clinic visits and two were completed via mail-in questionnaires. The optimal point of enrollment into SOFTAD was the final TADS follow-up visit, but participants could enroll in SOFTAD at any later visit. The first SOFTAD assessment occurred 6 months after TADS.

The clinic-based assessments were at SOFTAD Months 6, 12, 18, 30, and 42. Mail-in assessments occurred at Months 24 and 36. If participants were recruited into SOFTAD at a later point then their last TADS visit, their initial SOFTAD visit was marked to align with the next visit in the SOFTAD assessment sequence. Enrollment into SOFTAD was distributed as follows: Month 6(33.7%), Month 12(21.9%), Month 18(13.8%), Month 24(10.7%), Month 20(9.7%), Month 36(8.2%), Month 42(2.0%).

Assessment

Developmental Milestones

At enrollment participants updated a demographics form regarding living situation, education, and employment.

Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children – Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-P/L)

The K-SADS-P/L(29) was completed by Independent Evaluators to determine MDD and other psychiatric disorders according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–4th ed., text rev. The K-SADS-P/L also determined recovery from and recurrence of major depressive episodes (MDEs). An MDD “recurrence” constituted a new episode of MDD following at least 8 weeks without any clinically significant symptoms of an MDE. In the current study, recurrence was specifically defined as an MDE during the 3.5 years of follow-up in SOFTAD. The K-SADS-P/L also yielded diagnoses of anxiety, disruptive behaviors, and substance/alcohol abuse/dependence. Psychotic, eating, and tic disorders were assessed but not used due to small cell size.

Global Functioning

Global functioning was assessed using one of two measures depending on the participant age at time of assessment: the Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS(30)) or Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF(31)). Independent Evaluators, blinded to initial treatment condition, rated both measures at age-appropriate times, which consist of the same 100-point scale, where higher scores indicate better functioning. The CGAS was administered to all adolescents 18 years of age and younger, and the GAF was used for young adults 19 years or older. After administration, these ratings were combined into a single global functioning variable that consisted of the CGAS rating for participants 18 or under and GAF rating for participants 19 or older. Previous research suggests child and adult functional rating scales have a high degree of concordance(32). Further, functioning ratings on these measures in SOFTAD did not differ according to the measure used at any SOFTAD visit(all p's>.136).

Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Adolescents (HoNOSCA(17))

The HoNOSCA is clinician-rated measure that assesses behaviors, impairment, and social functioning in adolescents. Each HoNOSCA item is rated on a five-point scale (0=no problem;1-4 minor to severe problem). Items are summed to yield a total index of global clinical functioning. Higher scores indicate poorer functioning. The HoNOSCA has demonstrated adequate reliability(17) and validity with other measures of functioning(33, 34).

Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale (RADS(35))

The RADS is a 30 item, 4-point scale self-report questionnaire designed to assess depressive symptoms in adolescents. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms.

Statistical Analyses

Mixed-effects regression random intercept and trend models (MRMs;(36)) were conducted in SPSS to examine 1) trajectories of functional outcomes and 2) predictors of functioning and developmental milestones. MRMs are well-suited for longitudinal data analysis because they are robust to the data dependency that occurs with repeated assessments of individuals over time. MRMs are efficient in handling missing data by using all available data for a given participant to estimate group trends at each time point. Of the 196 participants enrolled in SOFTAD, 58%(n = 113) completed the 6 month, 67%(n = 131) completed the 12 month, 68%(n = 134) completed the 18 month, 68%(n = 134) completed the 30 month, and 70%(n = 138) completed the 42 month assessment. On average, participants completed 3.45 (SD=2.02) SOFTAD assessments. To evaluate whether data were missing at random, we examined whether age, depression severity, and global functioning at SOFTAD entry differed between those who completed SOFTAD and those who dropped out before Month 42. Reasons for selecting these variables to evaluate missing data included 1) participants may be more likely to drop out as they got older, 2) depression severity has predicted engagement in prior studies, and 3) global functioning was the primary outcome of the current investigation. None of these factors were significant.

Given the exploratory nature of the current hypotheses, the level of significance was set at p<.05 for each statistical test. Measures of functional outcomes included 1) global functioning as measured by the CGAS/GAF, 2) domains of functioning from the HoNOSCA, and 3) developmental milestones. MRM models included both fixed (time, site) and random (patient, patient-by-time) effects. Fixed effects predictors included: TADS initial treatment condition, MDE recurrence, and psychiatric comorbidities. To test hypothesis one (whether functioning would be maintained over treatment), site and time were entered in the first block of all models, to evaluate trajectories over time in global functioning. To test hypothesis two (whether initial treatment, relapse, or comorbidity predicted trajectories of poorer functioning or achievement of milestones), predictors were added separately into each model in a second block including fixed (predictor, time, predictor-by-time interactions, and site) and random (patient, patient-by-time) effects. The same models were run predicting factors derived from the HoNOSCA and developmental milestones. Although we did not hypothesize a quadratic effect, all models initially included quadratic effects for time to ensure we did not discount a better model fit. We also included linear effects for age to control for development. Linear effects of age and quadratic terms for time were removed if they did not reach significance. Significant model terms were probed with a posteriori pair-wise comparisons at each time point using the estimated marginal means subcommand with Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) comparisons.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

Average depressive severity at SOFTAD enrollment on the RADS was moderate (M=51.36, SD=14.60)(37). The distribution of SOFTAD participants based on their initial randomization was as follows: 23.5% FLX(n=46), 27% CBT(n=53), 25% COMB(n=49), and 24.5% PBO(n=48). SOFTAD completers (attended all subsequent assessments after enrollment) and non-completers did not differ in age (t=.18, p=.861), depression severity (t=.42, p=.673), or global functioning (t=.95, p=.344) at SOFTAD entry. Approximately 47%(n=92) of participants experienced a recurrent MDE during SOFTAD (described in detail in(20)). During the extended longitudinal follow-up, 54.6%(n=107) of participants met criteria for a comorbid psychiatric disorder (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of SOFTAD Adolescents

| Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| M | SD | |

| Age at Enrollment | 17.8 | 1.8 |

| N | % | |

| Race | ||

| White | 154 | 78.6 |

| African American | 16 | 8.2 |

| Latino | 18 | 9.2 |

| Female | 110 | 56.1 |

| Developmental Milestones at Enrollment | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Enrolled in School | 159 | 81.5 |

| Enrolled in College | 15 | 10.6 |

| Living Independently | 19 | 13.6 |

| Employed | 88 | 44.9 |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| M | SD | |

| Depression Severity at SOFTAD Enrollmenta | 51.4 | 14.6 |

| TADS Completion Depression Severitya | 53.38 | 16.65 |

| N | % | |

| MDD Recurrenceb | 92 | 46.9 |

| Psychiatric Co-morbidity During SOFTAD Period | 107 | 54.6 |

| Anxiety Disorderc | 31 | 15.8 |

| Behavioral Disorderd | 18 | 9.2 |

| Substance Use Disordere | 20 | 10.2 |

| Multiple Psychiatric Co-morbiditiesf | 38 | 19.4 |

| TADS Initial Treatment Assignment | ||

| Fluoxetine | 46 | 23.5 |

| CBT | 53 | 27.0 |

| Fluoxetine + CBT | 49 | 25.0 |

| Pill Placebo | 48 | 24.5 |

Depression severity as measured by Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale (RADS)

MDD relapse during SOFTAD

Anxiety disorders included general anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, social phobia, panic, agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, acute stress, and adjustment disorder.

Behavioral disorders included conduct, oppositional defiant, attention-deficit/hyperactivity, adjustment with disturbance of conduct, and adjustment with mixed mood/conduct.

Substance use disorders included substance abuse or dependence, alcohol abuse or dependence, and nicotine dependence.

Multiple Psychiatric Co-morbidities involved meeting criteria for any combination of two or more anxiety, behavioral, or substance use disorders.

Global Functioning

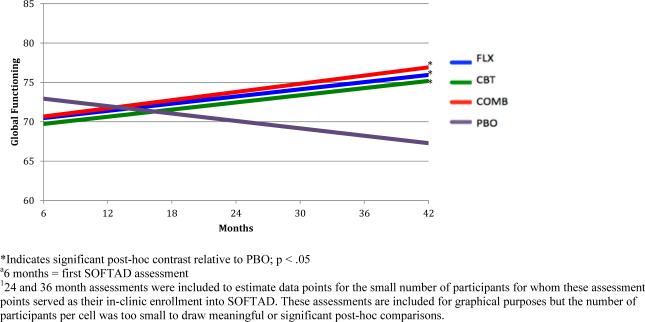

Average global functioning at SOFTAD entry (M=70.63, SD=14.12) corresponded with the CGAS/GAF scale rating of “some difficulty in a single area but generally functioning pretty well”. Global functioning improved linearly over time, b=.08, SE=.03, p=.013 (Table 2). At 42 months, average global functioning still fell within the same descriptive range, but improved slightly (M=74.00, SD=15.95), corresponding to a small effect size (d=.23). A significant time by initial treatment group interaction, b=−.06, SE=.03, p=.036 (Table 2) indicated that all adolescents receiving an active treatment (FLX, COMB, CBT) improved in global functioning over time. In contrast, adolescents originally assigned to PBO declined in functioning (Figure 1). Youth in the PBO arm did not have more comorbidities, increased depression severity, or differences in age (all p's>.107). Post-hoc tests indicated a trend for the superiority of COMB relative to PBO at SOFTAD month 30 (F=3.58, p=.061). At SOFTAD month 42, FLX (F=3.95, p=.049), CBT (F=4.52, p=.035), and COMB (F=5.69, p=.018) outperformed PBO.

Table 2.

Mixed Effects Regression Models Examining CGAS/GAF-by-time

| CGAS/GAF | ||

|---|---|---|

| Block 1: Time | Estimate | SE |

| Site | −.10 | .06 |

| Time | .08* | .03 |

| Block 2: Predictors of Functioning | ||

| Treatment | ||

| Treatment | .50 | 1.01 |

| Treatment × Time | −.06* | .03 |

| MDDa Recurrence | ||

| MDDa Recurrence | −13.1** | 2.31 |

| MDDa Recurrence × Time | −.01 | .08 |

| Psychiatric Co-morbidities | ||

| Psychiatric Co-morbidities | −2.32** | .69 |

| Psychiatric Co-morbidities × Time | −.05** | .02 |

p<.05

p<.01

MDD = Major Depressive Disorder

Figure 1.

Global Functioning -by-TADS Randomization over Extended Follow-up1

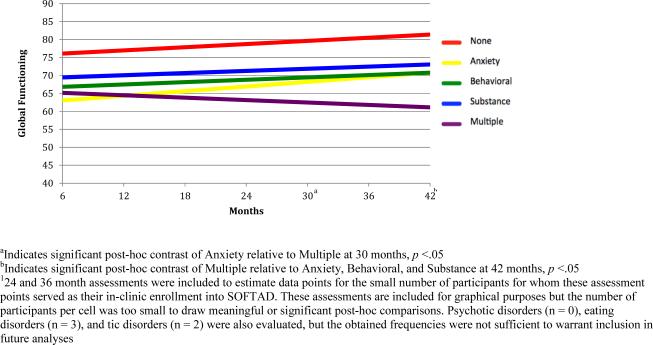

A significant time by comorbid psychiatric disorder interaction term, b=−.05, SE=.02, p=.009 (Table 2) indicated that individuals without psychiatric comorbidity during SOFTAD reached the highest level of global functioning, (all p's<.05; Figure 2). Adolescents meeting criteria for any one comorbidity (anxiety, behavioral, or substance use) also improved, whereas teens with multiple comorbidities declined in functioning. Teens with multiple comorbidities demonstrated poorer functioning compared to teens with an anxiety disorder at Month 30 (F=9.94, p=.001). By Month 42, teens with multiple comorbidities were functioning poorly compared to those with anxiety (F=5.44, p=.001), behavioral (F=5.79, p=.017), and substance use disorders (F=9.77, p=.002). MDE recurrence was a predictor of lower functioning across all assessment points (b=−13.1, SE=2.31, p<.001).

Figure 2.

Global Functioning-by-Psychiatric Comorbidity2

Domains of Functioning (HoNOSCA)

The HoNOSCA factored into three domains of functioning; internalizing, externalizing, and severe mental health impairment (see supplement). Functioning in all of these factor scores was consistently lower among teens with an MDE recurrence (Table 3). Post-hoc tests indicated this difference was present at all assessment points for internalizing impairment (all p's<.01), emerged and persisted after month 18 for externalizing impairment (all p's<.05), and emerged and persisted after month 12 for impairment related to severe mental health (all p's<.05).

Table 3.

Mixed Effects Regression Models Examining Domains of Functioning on the HoNOSCA and Developmental Milestones

| Internalizing Impairment | Externalizing Impairment | Severe Mental Health Impairment | Living Independent | College | Employment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: Time | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE |

| Site | .006 | .003 | .002 | .004 | .001 | .003 | −.004 | .04 | .06 | .05 | −.03 | .02 |

| Time | −.003 | .002 | −.001 | .002 | −.003 | .002 | .05 | .03 | .10 | .04* | .06 | .01** |

| Block 2: Predictors of Functioning | ||||||||||||

| Treatment | ||||||||||||

| Treatment | −.02 | .07 | −.03 | .07 | −.02 | .07 | −3.61 | 2.34 | −2.13 | 1.09 | −.28 | .29 |

| Treatment × Time | −.001 | .002 | .002 | .002 | .003 | .002 | −1.30 | .12 | .04 | .03 | .01 | .01 |

| MDDa Recurrence | ||||||||||||

| MDDa Recurrence | −.91** | .17 | −.42* | .18 | −.67** | .17 | −1.04 | 1.29 | −1.75 | 1.56 | −.61 | .72 |

| MDDa Recurrence × Time | .004 | .006 | .004 | .006 | .002 | .01 | .03 | .05 | .06 | .05 | .03 | .03 |

| Psychiatric Co-morbidities | ||||||||||||

| Psychiatric Co-morbidities | .05 | .05 | .30** | .05 | .06 | .05 | 1.15 | .93 | .51 | .59 | −.04 | .21 |

| Psychiatric Co-morbidities × Time | .004* | .001 | .003 | .01 | .003 | .01 | −.12 | .03** | −.02 | .02 | .01 | .01 |

p<.05

p<.01

MDD = Major Depressive Disorder

A significant interaction term of time by psychiatric comorbidity (Table 3) indicated that specific comorbidities predicted divergent trajectories in internalizing impairment, b=.004, SE=.001, p=.015. Individuals without a comorbid disorder during SOFTAD improved and showed the least internalizing impairment. Individuals with anxiety, behavioral, or substance use disorders as a sole comorbidity also improved moderately, whereas teens with multiple comorbidities showed worsening trajectories (Supplemental Table 2). Multiple comorbidities or a substance-use disorder predicted more externalizing impairment relative to teens with no comorbidity of anxiety at all assessment points (all p's<.01).

Developmental Milestones

At SOFTAD enrollment, 81.5%(n=159) of adolescents were enrolled in school; 10.6% of whom were enrolled in college(n=15). Approximately 45% of adolescents(n=88) were employed. Thirteen percent(n=19) were living independently. Likelihood of college or employment increased over time, even after controlling for age (Table 3). A significant time by psychiatric co-morbidities interaction term indicated that independent living increased at a faster rate among teens with a substance use disorder. Individuals with behavioral disorders were least likely and slowest at achieving independent living. At month 42, where cumulative percentages of independent living, college enrollment, and employment were highest, participants were an average age of 20.13 (SD =1.49).

Discussion

This study examined how treatment history and clinical characteristics influence long-term functioning of emerging adults who experienced adolescent-onset depression. There is a scarcity of research investigating the impact of depression on the achievement of developmental milestones and functioning during the transition to early adulthood. Given that depression with adolescent-onset typically sets individuals on a negative trajectory towards multiple episodes and a chronic, refractory course, this study is important in directing treatment and secondary prevention targets that could be tailored to this critical developmental phase.

These data paint a relatively optimistic picture for youth fortunate enough to receive treatment for early-onset depression. Approximately one year after completing treatment, average functioning was above clinical thresholds and not indicative of major impairment(30). Over the follow-up, global functioning was sustained and continued to improve gradually. This outcome is an improvement over the moderate/severe degree of impairment observed at TADS baseline prior to treatment(14). However, improvement during SOFTAD was gradual and of a small effect size (Cohen's d=.23). Thus, it is unclear to what extent this change had a meaningful impact in the daily living. Nonetheless, it is promising that developmental milestones (college and employment) became more likely over time.

It is sobering that youth randomized to PBO declined in functioning. Kennard and colleagues (2009) failed to find any significant harm or diminished response to subsequent treatment among teens initially assigned to PBO(28). It is also puzzling that the effect was not explained by demographic characteristics or over-representation of PBDO in the SOFTAD. It is noteworthy that at the assessments PBO participants began to separate from other conditions; average age was 18.5 and 19.5 years, respectively. This decline could represent an incubated effect triggered by the transition to emerging adulthood, when developmental milestones and stressors such as moving away from home, attending college, or obtaining gainful employment are often faced. We believe these results should be interpreted with extreme caution until replicated, especially because the magnitude of the effect is small. The good news is that long-lasting improvements in functioning were observed among teens initially assigned to active treatment.

Several subgroups of youth decline in global functioning. It is not surprising MDD recurrence predicted consistently lower functioning, consistent with the debilitating effect of depression on role fulfillment(38). Notably, youth experiencing MDD recurrence still demonstrated an overall positive trajectory, suggesting that sustained recovery is feasible; albeit at a slightly lower threshold of functioning compared to peers with sustained remission. Youth who met criteria for multiple comorbidities declined in functioning. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of examining maintenance treatments and secondary prevention. Treatment of residual depressive symptoms among adult populations(39) and modular intervention for youth with comorbidities(40), represent promising avenues for future research.

Existing measures to assess functioning do not allow for a nuanced examination of domain-specific impairment. MDD recurrence predicted poorer functioning in all HoNOSCA domains, whereas the presence of multiple-comorbidities was associated with internalizing and externalizing impairment. It is possible that adolescents with more comorbidities may not have faired as well in initial treatment, as the treatment delivered was aimed at specifically targeting MDD, not comorbid conditions. Substance-use was the only comorbidity uniquely related to externalizing impairment. Given that this factor consisted of problems with aggression and family functioning, these may be goals for functioning that treatment can address. Surprisingly, teens that used substances showed the highest rates of independent living. Substance use could lead to difficulties living at home with their families, or conversely, teens may be more likely to use drugs or alcohol when living in an unsupervised environment. In contrast, teens with behavioral disorders were least likely to achieve independent living over the follow-up, which could possibly reflect the difficulties with organization, motivation, and executive functioning that are characteristic of some behavioral disorders.

Strengths of this study include leveraging a large, randomized controlled trial with extended follow-up utilizing multiple measures of functioning. The current study is not without limitation. SOFTAD was an optional follow-up to TADS and did not capture all participants. Further, SOFTAD participants could enroll in the follow-up at any assessment point, making it difficult to estimate a true “initial illness severity” that is representative of the whole sample. The fact that the SOFTAD sample was comprised of participants who were younger, less likely to be a minority, had fewer comorbidities, and were more likely to be in their initial depressive episode than the overall TADS sample could represent a bias based on the illness severity of those who enrolled and were retained. We also were not able to control for differences in socioeconomic status because this data was not available. In particular, these differentiating factors could be associated with greater depressive symptoms, impairment, and resistance to treatment. Therefore, we caution that the findings may be only minimally representative of a select group of adolescents within a certain range illness severity. SOFTAD was also not designed with the power to test interactions for the selected outcomes. Although the study carries novelty in the use of factors of functioning derived from the HoNOSCA, this procedure, as well merging CGAS and GAF ratings, are methods that have yet to be validated in other studies and should be considered preliminary and in need of replication.

Nonetheless, our results are one of the first to show that early treatment may lead to long-lasting improvements in functioning. Early intervention during adolescence is important for promoting better functioning during emerging adulthood. However, depressive relapse and the onset of psychiatric comorbidities remain as obstacles during this critical transition. Future studies should examine effects of targeted interventions that prevent the recurrence of depression among remitted youth, as well as those that specifically target common co-occurring comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

Implications and Contributions.

The prognosis is positive for adolescents treated early for depression in regards to their ability to function as emerging adults, yet depressive recurrence and co-morbid disorders cause some teens persistent problems in functioning. Perhaps interventions specifically targeting functional outcomes could bolster sustained wellness during a critical period of development.

Acknowledgements

This study is dedicated to the memory of beloved colleague and mentor, David B. Henry.

Funding: This study was supported by grant NIMH R01-MH070494 (Curry (PI)) and an NIMH T32 MH067631 to (ATP)

Abbreviations

- MDD

Major Depressive Disorder

- TADS

Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study

- SOFTADS

The Survey of Outcomes Following Treatment for Adolescent Depression

- CBT

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- FLX

Fluoxetine

- COMB

Combination Treatment

- PBO

Placebo

- SSRI's

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor

- RCT

Randomized Controlled Trial

- MDE

Major Depressive Episode

- IPT

Interpersonal Psychotherapy

- CGAS

Children's Global Assessment Scale

- GAF

Global Assessment of Functioning

- HONOSCA

Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Adolescents

- MRM

Mixed Regression Models

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interests: Dr. Silva is a consultant to Pfizer. Dr. Henry has received honoraria and consultancies from Rush University, the Center for Alaska Native Health Research, and the University of Virginia Curry School of Education. The other authors have no financial interests or conflicts to report.

References

- 1.Birmaher B, Williamson DE, Dahl RE, et al. Clinical presentation and course of depression in youth: does onset in childhood differ from onset in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:63–70. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cairns KE, Yap MB, Pilkington PD, et al. Risk and protective factors for depression that adolescents can modify: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of affective disorders. 2014;169:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 2002;59:225–231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graber JA. Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and behavior. 2013;64:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheets ES, Craighead WE. Comparing chronic interpersonal and noninterpersonal stress domains as predictors of depression recurrence in emerging adults. Behaviour research and therapy. 2014;63:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vujeva HM, Furman W. Depressive symptoms and romantic relationship qualities from adolescence through emerging adulthood: a longitudinal examination of influences. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology : the official journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53. 2011;40:123–135. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. The development of romantic relationships and adaptations in the system of peer relationships. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2002;31:216–225. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee C, Gramotnev H. Life transitions and mental health in a national cohort of young Australian women. Developmental psychology. 2007;43:877–888. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry D. The relationship between depression and emerging adulthood: theory generation. ANS Advances in nursing science. 2004;27:53–69. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emslie GJ, Heiligenstein JH, Wagner KD, et al. Fluoxetine for acute treatment of depression in children and adolescents: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1205–1215. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller MB, Ryan ND, Strober M, et al. Efficacy of paroxetine in the treatment of adolescent major depression: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:762–772. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner KD, Ambrosini P, Rynn M, et al. Efficacy of sertraline in the treatment of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder: two randomized controlled trials. Jama. 2003;290:1033–1041. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.8.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brent DA, Holder D, Kolko D, et al. A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family, and supportive therapy. Archives of general psychiatry. 1997;54:877–885. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210125017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitiello B, Rohde P, Silva S, et al. Functioning and quality of life in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1419–1426. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242229.52646.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kocsis JH, Schatzberg A, Rush AJ, et al. Psychosocial outcomes following long-term, double-blind treatment of chronic depression with sertraline vs placebo. Archives of general psychiatry. 2002;59:723–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ustun B, Kennedy C. What is “functional impairment”? Disentangling disability from clinical significance. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:82–85. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gowers SG, Harrington RC, Whitton A, et al. Brief scale for measuring the outcomes of emotional and behavioural disorders in children. Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for children and Adolescents (HoNOSCA). The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1999;174:413–416. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodyer I, Dubicka B, Wilkinson P, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and routine specialist care with and without cognitive behaviour therapy in adolescents with major depression: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2007;335:142. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39224.494340.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood A, Trainor G, Rothwell J, et al. Randomized trial of group therapy for repeated deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1246–1253. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curry J, Silva S, Rohde P, et al. Recovery and recurrence following treatment for adolescent major depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 2011;68:263–269. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Axelson DA, Birmaher B. Relation between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Depression and anxiety. 2001;14:67–78. doi: 10.1002/da.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker SP, Luebbe AM, Langberg JM. Co-occurring mental health problems and peer functioning among youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review and recommendations for future research. Clinical child and family psychology review. 2012;15:279–302. doi: 10.1007/s10567-012-0122-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Neil KA, Conner BT, Kendall PC. Internalizing disorders and substance use disorders in youth: comorbidity, risk, temporal order, and implications for intervention. Clinical psychology review. 2011;31:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emslie GJ, Mayes TL, Laptook RS, et al. Predictors of response to treatment in children and adolescents with mood disorders. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2003;26:435–456. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawton K, Saunders KE, O'Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379:2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolaitis G. [Mood disorders in childhood and adolescence: continuities and discontinuities to adulthood]. Psychiatrike = Psychiatriki. 2012;23(Suppl 1):94–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004;292:807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennard BD, Silva SG, Mayes TL, et al. Assessment of safety and long-term outcomes of initial treatment with placebo in TADS. The American journal of psychiatry. 2009;166:337–344. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A children's global assessment scale (CGAS). Archives of general psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of general psychiatry. 1976;33:766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bird HR, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, et al. Further measures of the psychometric properties of the Children's Global Assessment Scale. Archives of general psychiatry. 1987;44:821–824. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210069011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garralda M, Yates P, Higginson I. Child and adolescent mental health service use HoNOSCA as an outcome measure. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177:52–58. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macgregor CA, Sheerin D. Family life and relationships in the health of the nation outcome scales for children and adolescents (HoNOSCA). Psychiatric Bulletin. 2006;30:216–219. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds WM. Reynolds adolescent depression scale: Wiley Online Library. 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curry J, Silva S, Rohde P, et al. Onset of alcohol or substance use disorders following treatment for adolescent depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2012;80:299–312. doi: 10.1037/a0026929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birmaher B, Bridge JA, Williamson DE, et al. Psychosocial functioning in youths at high risk to develop major depressive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:839–846. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000128787.88201.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watkins ER, Mullan E, Wingrove J, et al. Rumination-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy for residual depression: phase II randomised controlled trial. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 2011;199:317–322. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.090282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chorpita BF, Weisz JR, Daleiden EL, et al. Long-term outcomes for the Child STEPs randomized effectiveness trial: a comparison of modular and standard treatment designs with usual care. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2013;81:999–1009. doi: 10.1037/a0034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.