Abstract

Following microbial pathogen invasion, one of the main challenges for the host is to rapidly control pathogen spreading to avoid vital tissue damage. Here, we report that an effector CD8+ T cell population that expresses the marker NK1.1 undergoes delayed contraction and sustains early anti-microbial protection. NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells are derived from CD8+ T cells during priming, and their differentiation is inhibited by TGF-β signaling. After their own contraction-phase, they formed a distinct pool of KLRG1 CD127 double positive memory T cells and rapidly produced both IFN-γ and granzyme B, compared to NK1.1− counterparts, providing significant pathogen-protection in an antigen-independent manner within only a few hours. Thus, by prolonging the CD8+ T cell response at the effector stage and by expressing exacerbated innate-like feature at the memory stage, NK1.1+ cells represent a distinct subset of CD8+ T cell that contributes to the early control of microbial pathogen re-infections.

Introduction

CD8+ T cells have been largely depicted as potent effector lymphocytes in the eradication of numerous intracellular pathogens including bacteria and viruses. During CD8+ T cell response to an acute infection, naïve CD8+ T cells, carrying an appropriate T Cell Receptor (TCR), specifically recognize pathogen-derived antigens presented by MHC-I to undergo an activation-phase characterized by a vigorous proliferative burst, resulting in the formation of a large pool of effector T cells. This expansion is associated with the acquisition of effector functions. A large proportion of CD8+ T cells acquire cytotoxic molecules and effector cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α), and thus the capacity to kill infected cells, as well as to recruit or activate other cells of the immune system, resulting in effective pathogen clearance 1,2. The CD8 response typically peaks around 6–7 days after infection, and 90–95% of the effector T cells are then destroyed in the following days and weeks by apoptosis, whether the pathogen is totally eliminated or not 3. The fraction of effector cells surviving this contraction-phase will persist long-term in an antigen-independent manner in mice and humans 4. These memory cells can blunt the severity of a second infection, by proliferating and producing cytokines quickly after pathogen infection1. However, it has been reported that at the peak of expansion following certain infections or immunizations, a small fraction of cells exhibit features of memory antigen-specific cells 5,6. Their potential to proliferate and acquire effector function appears to be blocked by the presence of effector cells 6, and it takes around 40 days for these cells to acquire full memory cell qualities 7. Moreover, a few days are required to establish an efficient antigen-specific response by memory CD8+ T cells following a secondary microbial infection 8. Thus, the hollowing out of antigen-specific effector cells due to the contraction-phase delays the re-establishment of a fully effective arsenal of CD8+ T cells, and could lead aid early pathogen propagation upon rapid re-infection. Conversely, recent observations revealed a heterogeneity at the initiation of the contraction-phase depending on the priming conditions, suggesting that some effector CD8+ T cells could prolong protection due to their delayed contraction 9,10. Moreover, at the memory stage, we and others have reported that pathogen-specific CD8+ T cells can respond to inflammatory cytokines by producing both IFN-γ and granzyme B in an antigen-independent manner within a few hours following pathogen entry 11–15. Thus, in order to improve microbial pathogen-protection, it is essential to identify CD8+ T cell subsets that can either contract later and/or respond earlier to second infections, as well as to determine factors controlling their differentiation.

During the last decade, it has become clear that antigen-induced effector CD8+ T cells are phenotypically heterogeneous 16. At the peak of the response, cells harboring IL-7Rα (CD127) and lacking the killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 (KLRG1) were reported to survive the contraction-phase and give rise to memory cells, whereas KLRG1 positive cells were regarded as short-lived effector cells 1. Interestingly, other markers usually associated with NK cells have also been observed on some CD8+ T lymphocytes. Among them, the glycoprotein NK1.1 was reported at the surface of some CD8+ T cells during viral infections in both mice and humans 17–19. Although NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells have been described for more than a decade, their contribution in the CD8 response against microbial infection, as well as the factors controlling their differentiation in vivo, remains elusive.

We show that, upon viral or bacterial infections in mice, a fraction of CD8+ T cells can escape Transforming Growth Factor beta (TGF-β) control during priming, giving rise to NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells. These TGF-β-repressed CD8+ T cells represent a unique pathogen-specific subset. In contrast to their NK1.1− counterparts, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells undergo delayed contraction, and provide prolonged pathogen-specific reactivity to the host. The fraction of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells that survives the contraction-phase maintains KLRG1 surface-expression. These memory cells rapidly produce both IFN-γ and granzyme B, not only in response to pathogen-antigens, but also in an antigen-independent manner, providing an early protection against invading microbial pathogens. Overall, our results reveal both the origin and the function of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells, a key subset of T lymphocytes that sustains early CD8+ T cell-mediated host protection against microbial pathogen re-infections.

Results

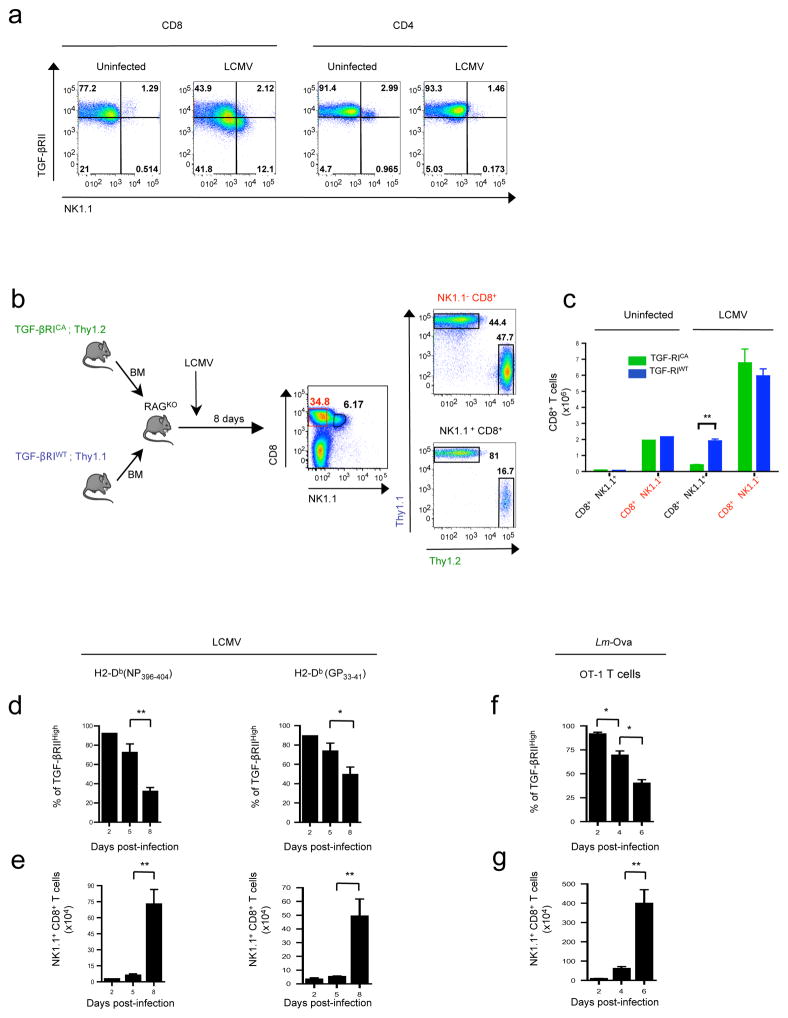

NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation is repressed by TGF-β signaling

CD8+ T cell heterogeneity is believed to be largely influenced by factors controlling the initial priming during microbial infection 20,21. Among the factors able to influence the differentiation of numerous T cell subsets, cytokines, and particularly TGF-β, are regarded as potent actors 22. This pleiotropic cytokine signals through a two-receptor complex composed of TGF-βRI and TGF-βRII. Signaling is initiated by the auto-phosphorylation of the TGF-βRII subunit, which in turn phosphorylates TGF-βRI, activating several signaling pathways 23. First, we sought to examine whether microbial infections affected sensitivity of T lymphocytes to TGF-β. Wild-type C57BL/6 (B6) mice were infected by lymphocytic choriomingitis virus Armstrong strain (LCMV), and TGF-βRII expression was analyzed at the surface of T cells 8 days later. Strikingly, infection was associated with a loss of expression of TGF-βRII at the surface of around half of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1a). This feature was confined to CD8+ T cells, since surface TGF-βRII expression remained almost stable on CD4+ T cells. Interestingly, in clear contrast with cells that maintained high levels of TGF-βRII expression, we found that the TGF-βRIIlow CD8+ population was enriched in T cells expressing the glycoprotein NK1.1 (Fig. 1a), whereas activated T lymphocytes, based on CD44, CD62L and Ly6C expression, were almost equally distributed between TGF-βRIIlow and TGF-βRIIhigh populations after LCMV infection (data not shown). After infection, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells were mainly observed within the spleen, the blood, and the liver, but were barely detectable in the lymph nodes and not found in the thymus (data not shown). Notably, in addition to NK1.1, we found that TGFβRIIlow CD8+ T cells also expressed high levels of various surface receptors characteristic of NK cells, including DX5, CD94, NKG2A/C/E, NKG2D and LY49C/I/F (Supplementary Figure 1a). Moreover, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells generated in response to LCMV, exhibited a diverse α,β TCR repertoire and their development was not impaired in CD1dKO LCMV infected mice, ruling out a potential NKT cell lineage origin for these cells (data not shown). The low levels of TGF-βRII at the surface of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells suggested that TGF-β signaling could repress the development of these cells. To verify this, we created mixed bone marrow (BM) chimera mice by reconstituting sub-lethally irradiated Rag–deficient mice (RAGKO) with BM (ratio 1:1) from both Thy1.1 B6 mice and Thy1.2 CD4-cre; LsL TgfbRICA B6 (TGFβ-RICA) mice. The latter express a constitutively active (CA) form of TGF-βRI selectively in their αβ T cells 24. In response to LCMV infection, we observed that very few NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells were derived from TGFβRICA BM, whereas NK1.1− CD8+ T cells were equally provided by both TGFβRICA BM and TGFβRIWT BM (Figure 1b–c) demonstrating the repressive effect of TGF-β on NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation. To follow the kinetics of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell appearance, we analyzed LCMV peptide-MHC-tetramer positive CD8+ T cells from day 2 to the peak of the response at day 8. In line with a decreasing sensitivity to TGF-β due to a gradual loss of TGF-βRII at the surface of CD8+ T cells from day 5 (Fig. 1d), significant numbers of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells were only detected after the fifth day of LCMV infection (Fig. 1e). It was notable that, like their NK1.1− counterparts, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells specific for LCMV antigen gradually acquired KLRG1 at their surface, (Supplementary Figure 1b–c), refuting the possibility that they are derived from KLRG1+ effector cells. Moreover, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation was also observed in the spleen of mice grafted with purified naïve NK1.1− CD8+ T cells from ovalbumin peptide (Ova) specific OT-1 TCR transgenic mice and infected with Listeria monocytogenes bacteria expressing Ova (Lm-Ova), ruling out a viral infection restricted effect and suggesting a differentiation of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells in response to microbial pathogen infection during priming of naïve NK1.1− CD8+ T cells before KLRG1 expression (Fig. 1f–g). Thus, this first set of data reveal that TGF-β directly influences the heterogeneity of the CD8+ T cell population by repressing the differentiation of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells from NK1.1− CD8+ T cells during microbial pathogen infections.

Figure 1. TGF-β signaling represses NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation.

(a) Flow cytometry analysis of TGF-(βRII and NK1.1 expression at the surface of either CD8+ T cell splenocytes or CD4+ T cell splenocytes 8 days after LCMV infection of B6 mice. Data are representative of 4 experiments with 3–4 animals per group. (b–c) T cell- depleted bone marrow (BM) cells from CD4-Cre; Stopfl/fl Tgf-/βRICA Thy1.2 B6 mice (TGF- βRICA) or Thy 1.1 B6 mice (TGF-βRIWT) were mixed at a 1:1 ratio and transferred into irradiated rag2KO mice (RAGKO). Chimeras were infected with LCMV 5 weeks later and splenocytes analyzed by flow cytometry 8 days post-infection for the BM origin of NK1.1+ CD8+ T splenocytes. (c) Graph illustrating the absolute number of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells and NK1.1− CD8+ T splenocytes derived from each BM donor (mean + SD, n=3 representative of 2 experiments). (d) Graph illustrating the percentage of both LCMV specific H2-Db(NP396–404) tetramer+ CD8+ splenocytes and LCMV specific H2-Db(GP33–41) tetramer+ CD8+ splenocytes expressing high levels of TGF-(βRII at different times after LCMV infection. (e) Graph illustrating absolute numbers of LCMV specific H2-Db(NP396– 404) and LCMV specific H2-Db(GP33–41) tetramer+ CD8+ splenocytes expressing NK1.1 at different times after LCMV infection. Data are representative of three experiments and shown as mean + SD n=5 per point. (f–g) Naïve (CD44low CD62Lhigh) OT-1 T cells were adoptively transferred into B6 mice, infected the following day by Lm-Ova. The graphs illustrate the percentage of OT-1 splenocytes expressing high levels of TGF-(βRII (f) and the absolute numbers of NK1.1+ OT-1 T cells at different times after Lm-Ova infection (g). Data are representative of 3 experiments and shown as mean + SD n=3 per point.

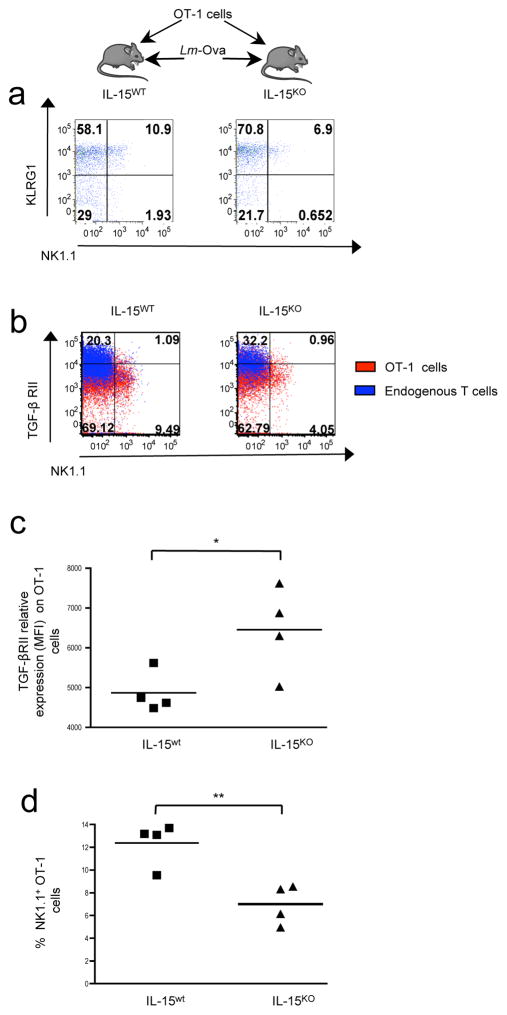

Dual role for IL-15 and TGF-β in NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation

Because inflammatory conditions during CD8+ T cell priming are known to influence the heterogeneity of the CD8+ T cells 20,21, we next investigated whether pro-inflammatory factors associated with microbial infection promote NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation. Since IL-15 levels can increase in response to infections 25,26, and IL-15 signaling has been proposed to repress of TGF-β signaling on cultured CD8+ T lymphocytes 27, we further assessed the contribution of IL-15 to NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation in vivo. For this, Il-15 competent (IL-15WT) or Il-15 deficient (IL-15KO) B6 mice were grafted with OT-1 cells and subsequently infected with Lm-Ova (Fig. 2a–d). Taking into consideration that IL-15 is critical for CD8+ T cell homeostasis 28, splenocytes were analyzed at day 6 after infection when the proportion of OT-1 KLRG1+ effector cells remained similar between il-15wt and il-15KO mice. However in the absence of IL-15, we observed a 50% reduction of NK1.1+ OT-1 cells, revealing a positive role for IL-15 on NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation (Fig. 2d). Moreover, TGF-βRII expression at the surface of OT-1 cells remained relatively high in il-15KO mice compared to that of grafted il-15wt animals, strongly suggesting that IL-15 signaling decreased the sensitivity of CD8+ T cells to TGF-β (Fig. 2b–d). Interestingly, in both IL-15 deficient and sufficient mice, the levels of TGF-βRII at the surface endogenous of T cells remained higher than that of OT-1 cells. In addition, endogenous T cells failed to differentiate efficiently in NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2b) implying that, in addition to cytokines produced during infection, such as IL-15, TCR engagement might also be required to enhance NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation. Altogether, these data revealed that, during infection, the differentiation of NK1.1− CD8+ T cells into NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells is influenced by a dual role of TGF-β and IL-15 during TCR priming. IL-15 facilitates TGF-β receptor down-regulation on CD8+ T cells, and their differentiation in NK1.1+cells.

Figure 2. TGF-β and IL-15 play a dual role in NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation.

(a–d) Tomato+ OT-1 CD8+ T cells were transferred into either IL-15 deficient mice or IL- 15 sufficient B6 mice infected the following day with Lm-Ova. (a) Flow cytometry analysis of the co-expression of NK1.1 and KLRG1 at the surface of OT-1 cells 6 days after infection. (b) Flow cytometry analysis of the co-expression of NK1.1 and TGF-βRII at the surface of either transferred or endogenous CD8+ T cells 6 days after infection. Quadrant digits indicate the proportion of cells expressing NK1.1 and TGF-βRII among the total CD8+ T splenocytes. (c–d) Graphs illustrate the proportion of NK1.1+ cells among CD8+ T splenocytes as well the mean of fluorescence intensity (MFI). These results are representative of 2 independent experiments with 4–5 recipient mice per group.

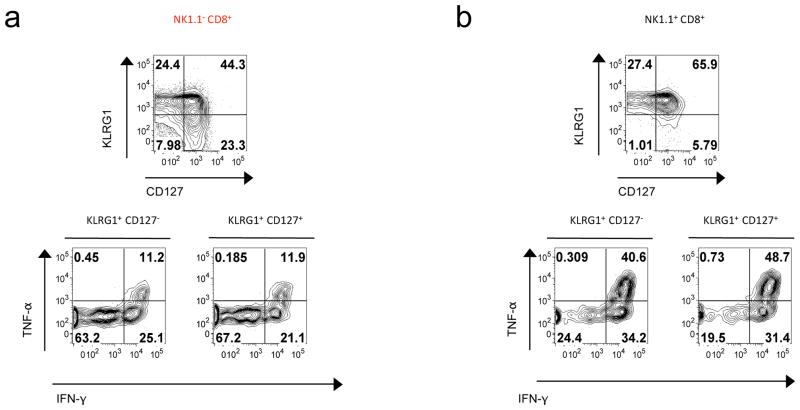

NK1.1+ CD8+ T lymphocytes are potent effector cells

It is well established that after recognition of pathogen antigens, CD8+ T cells undergo an activation-phase characterized by a vigorous proliferative burst in the first week of infection, resulting in the formation of a large pool of cells producing effector cytokines. We next assessed whether NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells were endowed with similar features in response to infectious agents. Using LCMV specific tetramers, we first compared NK1.1+ CD8+ and NK1.1− CD8+ T cell clonal expansion by giving mice drinking water containing 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) during the first 8 days following LCMV injection. We observed a modest, though not significant, increased proportion of BrdU+ among the NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells at day 5 after infection as compared to NK1.1− CD8+ T cells (data not shown). The up-regulation of CD44 and the down-regulation of CD62L, commonly used to monitor T cell-activation, was similar between NK1.1+ and NK1.1− LCMV specific CD8+ T cells, both at day 5 and day 10 after infection (data not shown). However, we found that LCMV-specific NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells were mainly KLRG1 positive 10 days after LCMV infection as compared to NK1.1− CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3a–b). Moreover, in clear contrast to their NK1.1− counterparts, NK1.1+ KLRG1+ CD8+ T cells massively expressed both IFN-γ and TNF-α ex-vivo in response to LCMV peptide stimulation (Fig. 3a–b). Notably, we did not find significant difference in granzyme B production between the two subsets, however a large proportion of NK1.1+ KLRG1+ CD8+ T cells expressed the degranulation associated molecule Lamp1 (CD107) at their surface compared to NK1.1− KLRG1+ CD8+ T cells (data not shown). Thus, these data reveal that, in response to infection, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells represent a potent effector CD8+ T cell population, and support the use of NK1.1 as a surface marker to discriminate CD8+ T cells with exacerbated effector functions.

Figure 3. NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells consist of activated and effector cells.

(a–b) B6 mice were infected by LCMV and their spleens analyzed 9 days later by flow cytometry. Expression of surface expression of KLRG1 and CD127 as well as IFN-γ and TNF-α production by H2-Db(NP396–404) tetramer+ CD8+ T cells after 3 hours of culture with LCMV NP396 peptide-pulsed APC. These results are representative of 2 independent experiments with 3mice per group.

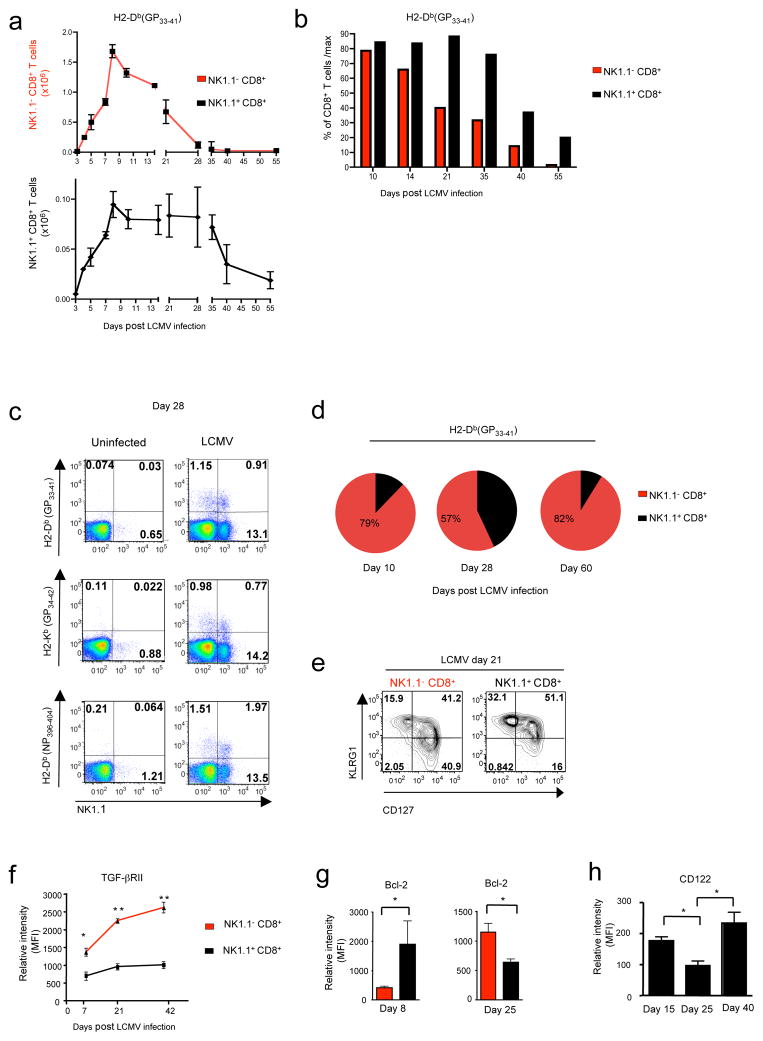

NK1.1+ CD8+ T lymphocytes are long-lived effector cells

The activation and expansion of effector cells is usually followed by a drastic reduction in their number due to large scale apoptotic death 2. We then monitored the numbers of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells and NK1.1− CD8+ T cells specific for a same LCMV immunogenic peptide at different time points post-infection (Fig. 4a). Surprisingly, while 60–70% of NK1.1− CD8+ T cells were lost between day 8 and 21 post-infection (Fig. 4 a–b), the population size of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells specific for the same LCMV peptide remained almost constant until the fourth week following infection, whereupon it started to significantly decrease. As a consequence of this delayed contraction, NK1.1+ CD8+ T lymphocytes, which represented only 10–15% of LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells at day 10, represented 40–60% of LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells at day 28, before returning to around 10% by day 60 (Fig. 4 c–d). Moreover, 3 weeks after infection twice more NK.1.1+ CD8+ T cells maintained the effector phenotype KLRG1+ CD127− compared to their NK1.1− counterparts (Fig. 4 e). This delayed contraction suggests that NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells could be more resistant than their CD8+ T cell counterparts to apoptosis. As TGF-β signaling in CD8+ T cells is known to promote apoptosis of effector CD8+ T cells during the contraction-phase 29,30, we next monitored TGF-βRII expression at the surface of CD8+ T cells at different time points after LCMV infection (Fig. 4f). Consistent with their survival advantage, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells maintained low levels of TGF-βRII at their surface, whereas TGF-βRII expression was gradually restored on NK1.1− CD8+ T cells. Supporting their enhanced ability to escape apoptosis, at the peak of expansion (day 8), NK1.1+ CD8+ T had higher expression of the anti-apoptotic molecule Bcl-2 compared to NK1.1− CD8+ T cells. In contrast, at three weeks post-infection, immediately prior to the drop in NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell numbers (Fig. 4a), they expressed slightly lower Bcl-2 levels than NK1.1− CD8+ T cells, which instead showed an increase in Bcl-2 levels (Fig. 4g). These data suggest that Bcl-2 dependent/TGF-β independent, late apoptosis of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells may involve a defect in IL-2 and/or IL-15 sensitivity, as supported by the lower level of CD122 surface expression observed only on NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells in the third week following infection (Fig. 4h). Thus, this set of data reveals that, while the number of effector NK1.1− CD8+ T cells rapidly decreases, the NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell population remains constant for a longer period and accounts for a large proportion of pathogen-specific effector CD8+ T cells in the weeks following the NK1.1− CD8+ T cell contraction.

Figure 4. NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells undergo a delayed contraction-phase.

(a) Graphs illustrating the absolute numbers of H2-Db(GP33–41) LCMV tetramer specific CD8+ T splenocytes at different times after B6 mice infection by LCMV. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with 3 mice per point. (b) Histograms represent the percentage of H2-Db(GP33–41) CD8+ T cells at different times after infection compared with their maximum at day 8 (100%). (c) Flow cytometry analysis of the proportion of several LCMV tetramer specific NK1.1+ and NK1.1− cells among CD8+ splenocytes 28 days after LCMV infection. (d) Diagrams illustrate the repartition of H2- Db(GP33–41) specific CD8+ splenocytes in NK1.1+ and NK1.1− cells at different times after LCMV infection. These results are representative of 3 independent experiments with 2–3 animals per group. (e) Flow cytometry analysis of the expression of KLRG1 and CD127 at the surface of H2-Db(GP33–41) specific NK1.1+ and NK1.1− CD8+ T cells from spleen 21 days after LCMV infection. (f–g) Mean of MFI (Mean Fluorescence Intensity +SD) of the expression of TGF-βRII and Bcl-2 in H2-Db(GP33–41) LCMV specific tetramer CD8+ T splenocytes at different times after LCMV infection. (h) Graphs represent mean of MFI (+SD) of the expression of CD122 on H2-Db(GP33–41) LCMV specific tetramer NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells at different times after LCMV infection. These results are representative of 2 independent experiments with 2–3 animals per time point.

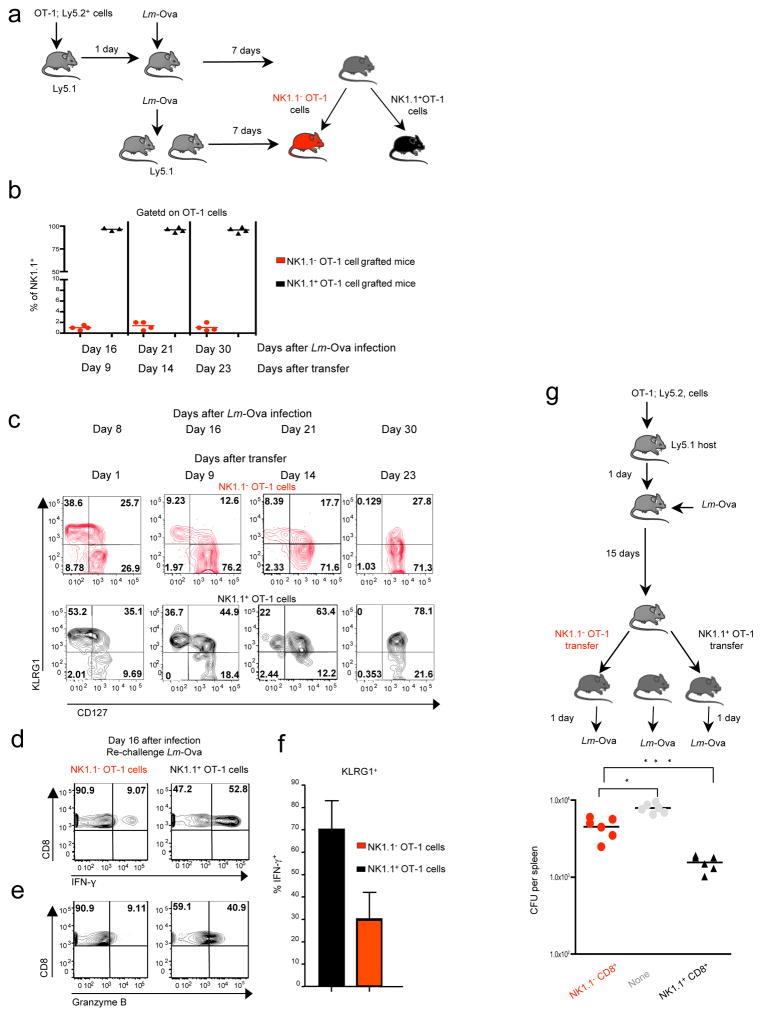

Interestingly, similar delayed contraction-phase of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells was also observed after Lm-Ova infection in mice previously transferred with OT-1 cells (Supplementary figure 2) excluding a pathogen specificity of this phenomena. We next took advantage of this OT-1 TCR transgenic model to monitor the individual outcome of both NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells and NK1.1− CD8+ T cells. We first adoptively transferred congenic B6 mice by injection of OT-1 cells and subsequently infected them with Lm-Ova. Seven days later, NK1.1+ and NK1.1− OT-1 cells were purified by flow-cell sorting and each population was separately transferred into Lm-Ova infected matched congenic recipient mice reproducing the same infectious and inflammatory environment as that of cell-donor mice (Fig. 5a). Transferred cells were analyzed on different days after infection. Notably, only a few % of the injected NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells had lost the NK1.1 marker at their surface and less than 5% of injected NK1.1− CD8+ T cells expressed low levels of NK1.1, likely due to poor fidelity of cell sorting, ruling out a major inter-conversion between these two populations that could explain their changes of proportion during the evolving CD8+ T cell response to infection (Fig. 5b). Given that coordinated expression of CD127 and KLRG1 has been proposed to distinguish short-lived effector cells (KLRG1high, CD127low) from those destined to develop into memory T cells (KLRG1−, CD127high)1, we then monitored the expression of these two markers at the surface of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells and NK1.1− CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5c). Both populations expressed mainly KLRG1 eight days after Lm-Ova infection, with a larger proportion of NK1.1+ CD8+ cells being KLRG1high. In total agreement with our observations made during LCMV infection (Fig. 3 a–b and Fig. 4e), in contrast to the NK1.1− CD8+ population that gradually lost KLRG1high cells to be replaced by KLRG1− CD127high cells, we found that the NK1.1+ CD8+ cells remained KLRG1high several weeks after Lm-Ova infection and gradually formed a KLRG1 CD127 double positive population (Fig. 5c). As the loss of KLRG1high CD8+ T cells (short-lived effector cells) was associated with an impairment of effector functions of the CD8 response in the weeks following the peak of the response 31, we next assessed whether NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells maintained their effector functions several weeks after infection. Mice immunized as in figure 5a were re-challenged with Lm-Ova two weeks later. As expected, few NK1.1− OT-1 cells were still able to produce both IFN-γ and granzyme B within 24 hours in response to recall infection. In contrast, approximately 50% of the NK1.1+ OT-1 cells were still endowed with strong effector functions (Fig. 5 d–e). It is notable that even among the KLRG1 positive cells, effector functions of NK1.1− OT-1 T cells were largely impaired compared to that of KLRG1+ NK1.1+ OT-1 T cells (Fig. 5f and not shown). Thus, these results imply that NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells are long-lived effector cells and that they could sustain the control of potential novel pathogen intrusion by rapidly mounting effector function compared to their NK1.1− counterparts. To further support this assumption, either NK1.1+ OT-1 cells or NK1.1− OT-1 cells purified from congenic B6 mice immunized with Lm-Ova 15 days prior, were separately grafted into B6 mice subsequently infected with Lm-Ova. One day later, we found a significantly reduced number of bacteria CFUs within the spleen of NK1.1+ OT-1 cell-grafted mice (Fig. 5g). Altogether, these results reveal NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells as a functionally distinct CD8+ population. Whereas NK1.1− CD8+ T lymphocyte numbers and effector functions rapidly decreased after infection, the NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell subset contracted substantially later and sustained prolonged effector functions and protection of the host, contributing to rapid anti-microbial CD8+ T cell response.

Figure 5. NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells remain long-lived effector cells.

(b–f) Host animals received either NK1.1+ OT-1 or NK1.1− OT-1 cells as illustrated in a. For the first transfer, 500 OT-1 cells were grafted, and for the second 105 cells purified NK1.1+ OT-1 and NK1.1− OT-1 were individually transferred in different hosts. (b) Graph illustrates the percentage of NK1.1+ cells among the OT-1 cells in the spleen of either NK1.1+ OT-1 cell grafted mice or NK1.1+ OT-1 cell grafted mice 9, 14 and 23 days after transfer. (c) Mice were analyzed at different time points after infection for the co- expression of CD127 and KLRG1 on grafted cells. Data are representative of 2 experiments with 3 mice per each time point. (d–e) Host mice were re-challenged with Lm-Ova at day 16 post-infection and the ability of OT-1 cells to produce IFN-γ and granzyme B monitored 24 hours later without in vitro re-stimulation. These results are representative of 2 experiments with 2–3 mice per group. (e) OT-1 cells were grafted in B6 mice infected the following day with Lm-Ova. Fifteen days later, NK1.1+ OT-1 cells and NK1.1− OT-1 cells were purified and 105 cells separately transferred into B6 mice that were infected the following day by Lm-Ova. The graph illustrates the colony forming units (CFU) observed per spleen 1 day after infection and is representative of 3 individual experiments.

Memory NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells exhibit an effector-memory like phenotype

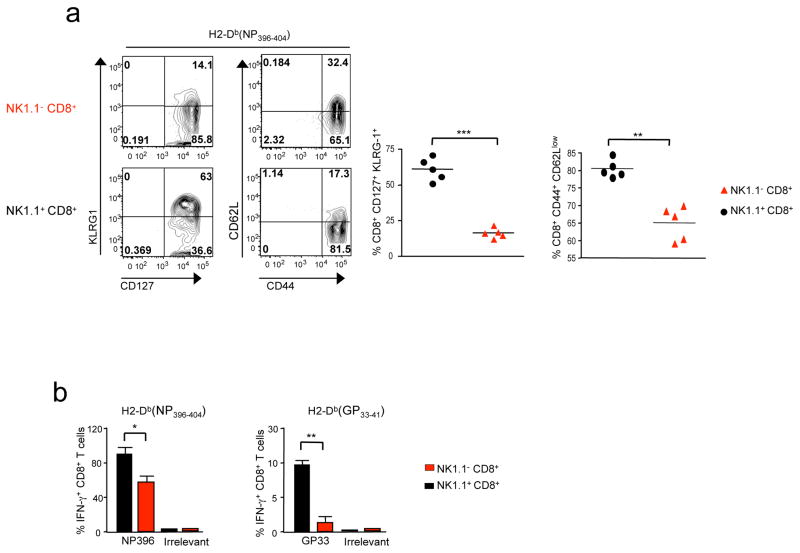

In humans and mice, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells comprise 5–10% of the memory CD8+ T cell population 19. Interestingly, at the memory stage, we found that they sustained low levels of TGF-βRII expression and had the same tissue tropism as NK1.1+ CD8+ effector T cells (Fig. 4e and data not shown). Surprisingly, two months after infection, KLRG1 CD127 double positive cells were still largely prevalent (~60–70%) within the subset of memory NK1.1+ CD8+ T splenocytes, whereas they only represented a small fraction (~10–15%) of the memory NK1.1− CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6a). Interestingly, a large proportion of NK1.1+ CD8+ memory T cells (~85%) were negative for the lymphoid organ homing molecule CD62L (Fig. 6a). As memory CD62Lneg T cells have been associated with an effector-memory like phenotype 32, we next examined the capacity of the NK1.1+ CD8+ memory T cells to rapidly produce IFN-γ in response to cognate pathogen peptide (Fig. 6b). In contrast to their NK1.1− counterparts, NK1.1+ CD8+ memory T cells specific for LCMV exhibited an exacerbated ability to rapidly produce IFN-γ after a short stimulation in vitro with cognate LCMV peptides, while maintaining their well-characterized difference of sensitivity between H2-Db(NP396–404) and H2Db(GP33–41) specific CD8+ T cells to their cognate antigen 33 (Fig. 6b). Thus, at the memory stage, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells represent a distinct subset of memory CD8+ T cells that were mainly composed of KLRG1 CD127 double positive cells, capable quickly mounting an effective effector response to pathogen-derived antigens.

Figure 6. NK1.1+ CD8+ T memory cells are effector memory-like T cells.

B6 mice were infected with LCMV 66 days previously. (a) Mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for the presence of H2-Db(NP396–404) tetramer+ cells expressing NK1.1, KLRG1, CD127, CD44 and CD62L. (b) Graphs illustrate the mean of LCMV specific tetramer+ CD8+ memory T cells producing IFN-γ 4 hours after in vitro re-stimulation with either cognate LCMV peptide (either NP396 or GP33) or irrelevant peptide (Ova). The mean of 2 experiments with 3–2 mice per groups (+SD) is illustrated.

NK1.1+ CD8+ memory T cells provide rapid innate immune protection

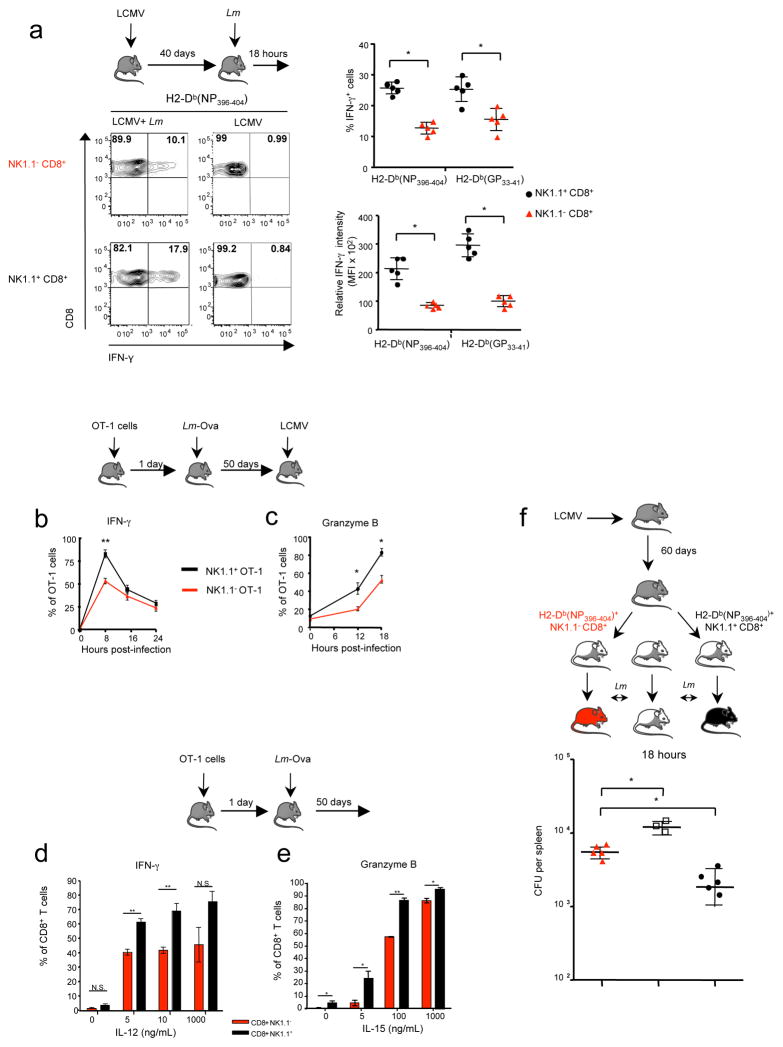

Similarly to NK cells, memory CD8+ T cells can be an early source of both IFN-γ and granzyme B in a cognate antigen-independent manner 34,35,13,14. It is notable that NK1.1+ CD8+ memory T cells expressed surface makers associated with NK cells (data not shown). In order to address whether NK1.1+ CD8+ memory T cells were also endowed with functional characteristics of innate immune cells, mice previously infected with LCMV were subsequently challenged with Lm a few months later. IFN-γ production by memory LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells was then assessed in response to Lm infection (Fig. 7a). Remarkably, within a few hours after Lm injection, we observed approximately 50% more IFN-γ+ cells among NK1.1+ CD8+ memory T cells compared to NK1.1− counterparts. Moreover, these IFN-γ+ NK1.1+ CD8+ memory T cells clearly expressed higher levels of IFN-γ (Fig. 7a). Similar observations were made in OT-1 memory cells generated in B6 mice grafted with OT-1 cells, primarily immunized with Lm-Ova and subsequently challenged with LCMV (Fig. 7b–c). Interestingly, a closer analysis of the kinetics revealed that NK1.1+ OT-1 memory splenocytes produced IFN-γ and granzyme B, both in larger frequency and more rapidly, compared to NK1.1− OT-1 memory cells. In line with recent observations showing that early production of IFN-γ and granzyme B is orchestrated by IL-15 and IL-12 14,13, we observed that NK1.1+ CD8+ OT-1 memory cells were more sensitive to both IL-15 and IL-12 than their NK1.1− counterparts (Fig. 7d–e). Thus these data reveal that memory NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells are endowed with exacerbated innate-like features and respond earlier and more dramatically than their NK1.1− counterparts to antigen non-specific, cytokine-mediated stimulation, suggesting an important role for this memory cell-subset in the early control of pathogen propagation within the host. To confirm this assumption, LCMV specific NK1.1+ or NK1.1− CD8+ T cells were purified by flow-cell sorting from mice immunized with LCMV 60 days prior and adoptively transferred into naïve syngenic mice. Recipients were subsequently infected by Lm and their spleens analyzed the next day to determine bacterial titers. We observed four to five fold reduction in bacterial CFUs in the spleen from mice grafted with LCMV specific NK1.1+ CD8+ memory T cells compared to mice grafted with NK1.1− cells (Fig. 7f). Altogether, these results support the idea that, among the memory CD8+ T cells, the NK1.1+ subset represents a unique subset that contributes efficiently to the early protective immune response against microbial pathogens.

Figure 7. Memory NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells produce rapidly IFNγ and granzyme B in an innate-like manner and are recruited to the sites of inflammation.

(a) Mice were infected by LCMV and subsequently re-infected or not 40 days later by Lm. Percentages of H2-Db(NP396–404) tetramer positive memory cells producing IFN-γ 14 hours after Lm infection are represented. Graphs illustrate either the percentage of IFN- γ positive memory cells or their mean fluorescence intensity in spleen. (b–c) CD8+ T cells from OT-1 Rag2KO were grafted in B6 mice infected the following day with Lm-Ova. 50 days later, animals were infected with LCMV. The percentage OT-1 memory cells (H- 2Kb(Ova) tetramers+) expressing IFN-γ and granzyme B at different hours post LCMV infection are illustrated by graph a and c respectively. Data are representative of 2–3 experiments with 3–5 animals per time points. (d–e) CD8+ T cells from OT-1 Rag2KO were grafted in B6 mice infected the following day with Lm-Ova. 50 days later, splenocytes were incubated with different concentrations of IL-15 and IL-12 for 12 hours and the production of IFN-γ and granzyme B by H-2Kb(Ova) tetramer positive CD8+ T cells monitored by flow cytometry. Graph illustrates the mean of the percentage of IFN-γ and granzyme B (n=4 +SD). (f) B6 mice were infected by LCMV 60 days earlier, H2-Db(NP396–404) tetramer specific NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells and NK1.1− CD8+ T cells were purified and separately grafted into B6 mice (5.103 cells per recipient). Recipient animals were then infected the next day by Lm. Graph illustrates Lm titration (Colony Forming Unit: CFU) in the spleens of different recipient animals 18 hours later. Results are representative of 2 experiments with 3–4 animals per group.

Discussion

After microbial pathogen invasion, one of the main challenges for the host is to rapidly control pathogen propagation to avoid vital tissue-damage. Our results reveal that a unique subset of CD8+ T cells that express NK1.1 at their surface contribute to the early CD8 response to microbial recall infections, both at the effector and memory stage. In contrast with their NK1.1− counterparts, for which both numbers and activity rapidly decrease after infection, the effector NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells are maintained longer and sustain prolonged microbiocidal activity. These long-lived effector cells ensure a rapid response to secondary microbial pathogen infections occurring during the period when pathogen specific effector T cells are massively reduced and the memory CD8 response is not yet fully established 7. Later, after undergoing contraction, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells compose a pool of memory cells, expressing both KLRG-1 and CD127, endowed with exacerbated adaptive response and innate-like features, contributing again to the early control of microbial pathogen re-infections both in an antigen-dependent and independent manner.

It is well known that after infection, the expression levels of Tgfbr1 and Tgfbr2 complexes are rapidly down regulated after TCR engagement CD8+ T cells, either individually or together, to be gradually restored during the proliferation phase 36. Our findings reveal that TGF-β represses differentiation of naïve NK1.1− CD8+ T cells in NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells during infectious episodes, since CD8+ T cells that cannot control TGF-β signaling, fail to differentiate into NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells. Given that NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells were found in non-divided cells and KLRG1− cells, we propose that their differentiation occurs during the initial priming-phase, likely before CD8+ T cells undergo significant expansion. This idea is strongly comforted by the absence of generation from effector cells from the peak of the response. Moreover, contrary to NK1.1− CD8+ T cells, the NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells keep low levels of expression of TGF-βR at their surface all their life long. Our work strongly suggests that the concerted action of inflammatory factors produced during infection, such as IL-15, is necessary for optimal CD8+ T cell differentiation into NK1.1+ cells. However like for numerous genes of klrg cluster, the expression klrb1c, encoding for NK1.1, seems dependent on STAT-5 but not directly regulated by this IL-15 activated transcription factors 37. Although our results in vivo indicate that IL-15 signaling contributes to the down-regulation of TGF-βR and enhances NK1.1 expression at the surface of CD8+ T cells, they do not rule out additional suppressive effects of IL-15 signaling downstream of the TGF-β receptor, as suggested in T cells in vitro27, and the contribution of other inflammatory factors working in concert with IL-15. Whether NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell differentiation occurs in the vicinity of cells selectively producing inflammatory cytokines in response to infection remains to be addressed. Interestingly, NK1.1 is a glycoprotein also expressed on NK cells and CD1d-dependent NKT cells, both lymphoid subsets that share several other NK surface markers and similar tissue tropism with NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells. It is notable that a similar dual role for IL-15 and TGF-β on NK1.1 expression has been also reported during the thymic development of CD1d-dependent NKT subsets 38,39. Whilst the function of NK1.1 remains unclear, due to the absence of identified ligand in mice 19, we do not exclude that NK1.1 expression by CD8+ T cells could reflect a differentiation stage of small numbers of pre-existing precursor cells, as for NK cells and CD1d-dependent NKT cells 38,39. Such a hypothesis would explain why only a restricted proportion of TGF-βRlow CD8+ T cells acquire the NK1.1 glycoprotein. As reported for NK cells NKT cells 40, NK1.1 seems not playing role in NK.1.1+ CD8+ T cell development or function in vivo since, in Balb/c mice that contrary to Humans and C57BL/6 mice do not expression NK.1.1 (CD161), CD8+ T cells expressing the other markers associated with NK.1.1 (Supplemental figure 1) were still present and endowed with exacerbated effector functions (data not shown).

Like their NK1.1− counterparts, NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells progress from effector cells to memory cells, however we revealed that they behave on the fringes of the current paradigm. During a primary infection, it is well documented that most CD8+ T cells entering into effector end-stage have a shortened life-span and die following infection, while a smaller proportion of cells differentiate into memory cell precursors 1. This longer survival of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells is in agreement with previous gene expression analysis showing that klrb1c expression is enriched in pathogen specific CD8+ T cells during the contraction-phase41. Moreover, unlike certain effector cells, like Th1742, differentiated NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells seem stable at least under inflammatory conditions we analyzed them. We propose that effector NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells fit into a unique differentiated CD8+ T cell population with a longer effector life-span accounted for by delayed contraction and sustained effector abilities. Notably, during both viral and bacterial infections, a wave of TGF-β production has been observed concomitantly to the beginning of the contraction-phase 29,43 TGF-β signaling in effector CD8+ T cells was reported as essential to promote their large-scale death by apoptosis, since CD8+ T cells expressing a dominant negative TGF-βRII survive much longer and maintain prolonged expression of high levels of Bcl-2 29. We found that NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells maintain low surface levels of TGF-βR throughout their life-span. Hence, in contrast to the majority of effector CD8+ T cells, they can control the pro-apoptotic effects of TGF-β and thus survive longer. This escape from apoptosis could explain why, several weeks after infection, effector NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells are still largely composed of KLRG1high CD127low cells, a population that has been reported with shortened life in many acute infections 1. Though we do not rule out a role for other factors, such as IL-15 described to promote survival during the contraction-phase 44, the contribution of IL-15 in the delayed contraction of NK1.1− CD8+ T cells is likely tenuous, since NK1.1+ CD8+ T effectors still contract later than their NK1.1− counterparts in IL-15 deficient mice (data not shown). Thus, our results suggest that control of TGF-β sensitivity by programming TGF-βR expression might determine which antigen-specific CD8+ T cells may survive longer and prolong the anti-microbial response while the majority of the effector cells are dying.

After contraction, and in contrast to NK1.1− CD8+ T cells, NK1.1+ cells gradually accumulate as double positive KLRG1 CD127 cells, a component of resting memory cells usually poorly represented among the bulk of memory CD8+ T cells. KLRG1high CD127high CD8+ memory T lymphocytes have been associated with cells that have experienced multiple infections by the same pathogen 45,46. Although unlikely, we cannot exclude that NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells could interact with some antigen-presenting cells, sustaining prolonged pathogen-derived antigen presentation. We propose that, like NK1.1, the expression of KLRG1 is maintained at the surface of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells throughout their life-span. We reported that NK1.1+ CD8+ memory T cells can efficiently and rapidly mount an adaptive immune response against pathogen-derived antigens. Such functional ability could be explained by their diminished sensitivity to the well-characterized TGF-β-suppressive effects on both inflammatory and cytotoxic differentiation programs 47,48 due to their sustained low expression of TGF-βR.

Adaptive immune response of memory CD8+ T cells is considered to be a powerful response to re-infection, however it only becomes fully efficient after a few days 8, a delay during which pathogens could exploit weaknesses to progress in the organism. However, like NK cells, in response to a subsequent pathogen infection, memory CD8+ T cells have been described as producers of an early source of effector cytokines and cytotoxic molecules in a cognate antigen independent manner 34,35,13,14. This innate-like feature has recently been demonstrated to be induced in vivo through inflammasome activation, triggered by various microbial pathogen infections 14. Memory CD8+ T cells are sensitive to inflammatory cytokines produced early by either dendritic cells 13 or inflammatory monocytes 14. Even though they represent a small fraction of memory CD8+ T cells, we propose that memory NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells constitute a potent early line of defence against microbial pathogens by responding earlier and more efficiently than their NK1.1− counterparts. Whether the expression of other NK associated markers and their tissue tropism contribute to the ability of the memory NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell subset to control early infection, remains to be addressed.

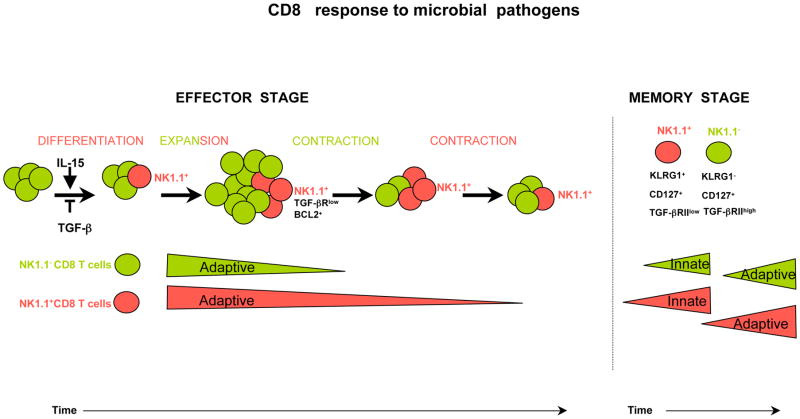

In summary, our work revealed that, during infection, a part of primed T cells will escape from TGF-β signaling, by down-regulating TGF-βR and can give rise to the NK1.1+ CD8+ T cell subset. This unique population contributes to the early response to pathogen re-infection due to its prolonged microbiocidal activity by effector cells and its exacerbated innate-like features as memory T cells. Therefore, we propose that the NK1.1+ CD8+ subset complements the action of the arsenal of CD8+ T cells during early response against microbial pathogens as illustrated by figure 8. Consequently, the development of vaccination adjuvants facilitating the differentiation of this subset will be of wide interest to speed up the control of pathogen propagation and thus to improve vaccine protection.

Figure 8. Schematic overview of the difference between NK1.1− CD8+ T cells and NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells responses to microbial pathogen.

In response to microbial infection, a fraction of CD8+ T cells can differentiate into NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells. This differentiation is blocked by TGF-β and enhanced by IL-15. While NK1.1- cells, in green, rapidly contract and loss their adaptive effector function, cells that acquire the NK1.1 marker, in red, contract much later and sustain longer effector functions and host protection. At the memory stage, NK1.1+ cells respond rapidly and strongly to pathogen in an innate-like manner, and develop more rapid and efficient adaptive memory response than their CD8+ memory T cell counterparts.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6) mice, B6 Thy.1.1 congenic mice and OT-1 and Rag2KO mice were purchased from Charles-Rivers (France). B6 CD4-Cre; Stopfl/flTgf-βRICA transgenic animals were generated as previously described 24. IL-15KO mice were purchased from Taconic, Rockville MD. Tomato-OT-1 mice were generated as previously described 14. CD1dKO mice were provided by Dr L. Van Kaer (Vanderbilt University, Nasville, TN). Mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free animal facility at the “PBES” (Lyon, France) and AniCan (Lyon, France) or SPF animal facility (AECOM). Animal experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations by the animal use committees CECCAPP at the CRCL and at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Viral and bacterial infections and peptide immunization

LCMV Armstrong was kindly provided by Dr R. Ahmed (Atlanta, USA) and amplified in BHK-21 cells as described 49. 2.105 PFU of Armstrong strain were injected i.p. for acute infection. Both Lm 10403s and Lm-Ova, expressing Ovalbumin (Ova) peptide were provided by Dr H. Shen. Bacteria were adapted to mice as described 29. 2000–5000 bacteria were injected i.v.. Bacterial titration was performed from spleen extract on Brain Heart Infusion soft agar (Fluka). Peptide immunization was performed by 2 intra-peritoneal injections over two subsequent days with 50nM of Ova (SIINFEKL) (NeoMPS, Strasbourg, France) diluted in PBS (Invitrogen).

Lymphocyte isolation, purification and transfer

Cell suspensions were prepared from spleen, liver, thymus, blood and peripheral lymph nodes as described previously 47. CD8+ T cells were purified using anti-CD8 conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi, France). Enriched CD8+ T cells fraction was then stained for NK1.1+ and CD8+ as well as CD44, CD62L or LCMV specific tetramers or Thy1.2 when indicated and sorted using a two laser BD FACS Aria (BD Biosciences) cell sorter/analyzer. 500–1000 of purified naïve OT-1 cells were transferred i.v. into mice.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

Anti-mouse Bcl-2, BrdU (3D4), CD4 (GK1.5), CD5 (53 7.3) CD8 (53-6.7), NK1.1 (PK136), CD44 (IM-7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD90.1 (HIS51), CD90.2 (53-2.1), CD94 (18d3 CD127 (A7R34), CD107, DX5 (DX5), NKG2A/C/E (20d5) NKG2D (C7), IFN-γ (XMG 1.2), KLRG1 (2F1), LY49C/I/F Ly6C (AL-21), TCR-β (H57-597), and TNF-α (MP6-XT22) and streptavidine were purchased from BD Biosciences (France) or eBioscience (France). Anti-mouse TGF-βRII (BAF532), was purchased from R&D Systems and anti-human granzyme B (GB11) was purchased from Invitrogen. Intracellular and intra-nuclear staining were performed using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) and FoxP3 staining buffer kit (ebioscience) respectively, according to provider guidelines. For cytokine staining, when indicated, splenocytes were incubated with LCMV NP396 (FQPQNGQFI) peptide or with LCMV GP33 (KAVYNFATC) (NeoMPS, Strasbourg) for 4 hours, in the presence of 1μg/mL Golgi Plug (BD Biosciences). LCMV iTAg™ MHC Tetramer NP396 (FQPQNGQFI) Allele H-2 Db/PE and iTAg™ MHC Tetramer GP33 (KAVYNFATC) Allele H-2Db/PE GP34/PE and Ova iTag™ Tetramer Ova (SIINFEKL) Allele H-2Kb/PE were purchased from Beckman Coulter (France) and provided by the NIH tetramer facility. Flow cytometry analysis was carried out on Canto II and Fortessa cytometers (BD Biosciences).

Bone marrow chimeras

Bone marrow cells from Thy1.1 C57BL/6 mice and Thy1.2 C57BL/6 CD4-Cre; Stopfl/flTGF-bRICA mice were isolated and depleted of CD3+ cells using Miltenyi-Biotec anti-CD3 beads. One million cells of each genotype were mixed (1:1) and transferred intravenously into irradiated Rag2KO recipient mice (8 Gray). Mice were infected 6 weeks after transfer by LCMV Armstrong.

BrdU administration

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine BrdU (Sigma) was given to animals in their drinking water 0.8mg/mL at the time infection and for 8 further days.

In vitro culture

Splenocytes were incubated for 14 hours at 37°C in the presence of either mouse recombinant IL-15 (R&D) or mouse recombinant IL-12 (Peprotech) in RPMI (10% foetal calf serum, 2mM L-Glutamine, 100U/L Penicillin Streptomycin, 1mM Hepes) with Golgi Plug (BD Biosciences).

TCR repertoire

Purified DNA from NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells was analyzed for Vβ chain diversity (Immun ID, Grenoble, France).

Statistics

Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test were used to assess the significance of differences observed between two groups with GraphPad Prism software P values are given as: (*) P<0.05; **P <0.001, *** P<0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. McCarron, C. Havenar-Daughton and A. Hennino for their comments. The technical assistance of J-F Henry, J. Noiret, C. Maisin, C. Faure and C. Garcia and A. Barbaz is acknowledged. We thank C.B. Wilson, L for CD4-Cre, as well as R. Ahmed, and H. Shen for providing us with LCMV and listeria respectively. Tetramers were kindly provided by the NIH Tetramer facility (NIH, USA). We also thank all the members of our laboratories for advice and helpful discussion as well as Sarah Kabani for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from ANR-08-JCJC-0005- 01 (JM), InCa Atip-Avenir program (JCM), FRM INE20091217951 (JCM), le comité du Rhone ligue (JCM), ANR investissement d’avenir ANR-10-LABX-61 (JCM). A L. R. was supported by the Bettencourt-Schuller foundation and the Helmholtz-association. This work was also supported by institutional funds of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University (GL), the National Institute of Health (Grants R21AI095835 and R01AI103338, GL). Core resources that facilitated flow cytometry were supported by the Einstein Cancer Center (NCI cancer center support grant 2P30CA013330). JCM is an Helmholtz-Association investigator

Footnotes

The authors declare to have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- 1.Cui W, Kaech SM. Generation of effector CD8+ T cells and their conversion to memory T cells. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:151–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sprent J, Surh CD. T cell memory. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:551–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100101.151926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mescher MF, et al. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murali-Krishna K, et al. Persistence of memory CD8 T cells in MHC class I- deficient mice. Science. 1999;286:1377–81. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badovinac VP, Harty JT. Programming, demarcating, and manipulating CD8+ T-cell memory. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:67–80. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong P, Lara-Tejero M, Ploss A, Leiner I, Pamer EG. Rapid development of T cell memory. J Immunol. 2004;172:7239–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaech SM, Hemby S, Kersh E, Ahmed R. Molecular and functional profiling of memory CD8 T cell differentiation. Cell. 2002;111:837–51. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmermann C, Prevost-Blondel A, Blaser C, Pircher H. Kinetics of the response of naive and memory CD8 T cells to antigen: similarities and differences. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:284–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199901)29:01<284::AID-IMMU284>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrod KR, et al. Dissecting T cell contraction in vivo using a genetically encoded reporter of apoptosis. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1438–47. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zehn D, Lee SY, Bevan MJ. Complete but curtailed T-cell response to very low-affinity antigen. Nature. 2009;458:211–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Sun S, Hwang I, Tough DF, Sprent J. Potent and selective stimulation of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in vivo by IL-15. Immunity. 1998;8:591– 9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg RE, Crossley E, Murray S, Forman J. Memory CD8+ T cells provide innate immune protection against Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of cognate antigen. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1583–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kupz A, et al. NLRC4 inflammasomes in dendritic cells regulate noncognate effector function by memory CD8(+) T cells. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:162–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soudja MS, Ruiz A, Marie JC, Lauvau G. Inflammatory monocytes switch on memory CD8+ T and innate NK lymphocytes during microbial pathogens invasion. Immunity. 2012;14:12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu T, et al. Bystander-activated memory CD8 T cells control early pathogen load in an innate-like, NKG2D-dependent manner. Cell Rep. 2013;3:701–8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaech SM, Wherry EJ. Heterogeneity and cell-fate decisions in effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation during viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kambayashi T, et al. Emergence of CD8+ T cells expressing NK cell receptors in influenza A virus-infected mice. J Immunol. 2000;165:4964–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slifka MK, Pagarigan RR, Whitton JL. NK markers are expressed on a high percentage of virus-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:2009–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fergusson JR, Fleming VM, Klenerman P. CD161-Expressing Human T Cells. Front Immunol. 2011;2:36. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harty JT, Badovinac VP. Shaping and reshaping CD8+ T-cell memory. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:107–19. doi: 10.1038/nri2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, Ahmed R. From vaccines to memory and back. Immunity. 2010;33:451–63. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubtsov YP, Rudensky AY. TGFbeta signalling in control of T-cell-mediated self-reactivity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:443–53. doi: 10.1038/nri2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–84. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartholin L, et al. Generation of mice with conditionally activated transforming growth factor beta signaling through the TbetaRI/ALK5 receptor. Genesis. 2008;46:724–31. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mortier E, et al. Macrophage- and dendritic-cell-derived interleukin-15 receptor alpha supports homeostasis of distinct CD8+ T cell subsets. Immunity. 2009;31:811–22. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colpitts SL, et al. Cutting edge: the role of IFN-alpha receptor and MyD88 signaling in induction of IL-15 expression in vivo. J Immunol. 2012;188:2483–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benahmed M, et al. Inhibition of TGF-beta signaling by IL-15: a new role for IL-15 in the loss of immune homeostasis in celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:994–1008. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyman O, Purton JF, Surh CD, Sprent J. Cytokines and T-cell homeostasis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:320–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanjabi S, Mosaheb MM, Flavell RA. Opposing effects of TGF-beta and IL-15 cytokines control the number of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;31:131–44. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takaku S, et al. Induction of apoptosis-resistant and TGF-beta-insensitive murine CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for HIV-1 gp160. Cell Immunol. 2012;280:138– 47. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang M, et al. Differential survival of cytotoxic T cells and memory cell precursors. J Immunol. 2007;178:3483–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wherry EJ, et al. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:225–34. doi: 10.1038/ni889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallimore A, Dumrese T, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM, Rammensee HG. Protective immunity does not correlate with the hierarchy of virus-specific cytotoxic T cell responses to naturally processed peptides. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1647– 57. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kambayashi T, Assarsson E, Lukacher AE, Ljunggren HG, Jensen PE. Memory CD8+ T cells provide an early source of IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2003;170:2399–408. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berg RE, Forman J. The role of CD8 T cells in innate immunity and in antigen non-specific protection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peixoto A, et al. CD8 single-cell gene coexpression reveals three different effector types present at distinct phases of the immune response. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1193– 205. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grange M, et al. Active STAT5 regulates T-bet and eomesodermin expression in CD8 T cells and imprints a T-bet-dependent Tc1 program with repressed IL- 6/TGF-beta1 signaling. J Immunol. 2013;191:3712–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doisne JM, et al. iNKT cell development is orchestrated by different branches of TGF-beta signaling. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1365–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Havenar-Daughton C, Li S, Benlagha K, Marie JC. Development and function of murine RORgammat+ iNKT cells are under TGF-beta signaling control. Blood. 2012;119:3486–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-401604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun JC, Lanier LL. NK cell development, homeostasis and function: parallels with CD8(+) T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:645–57. doi: 10.1038/nri3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doering TA, et al. Network analysis reveals centrally connected genes and pathways involved in CD8+ T cell exhaustion versus memory. Immunity. 2012;37:1130–44. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirota K, et al. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:255–63. doi: 10.1038/ni.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su HC, Ishikawa R, Biron CA. Transforming growth factor-beta expression and natural killer cell responses during virus infection of normal, nude, and SCID mice. J Immunol. 1993;151:4874–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melchionda F, et al. Adjuvant IL-7 or IL-15 overcomes immunodominance and improves survival of the CD8+ memory cell pool. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1177–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI23134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masopust D, Ha SJ, Vezys V, Ahmed R. Stimulation history dictates memory CD8 T cell phenotype: implications for prime-boost vaccination. J Immunol. 2006;177:831–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Obar JJ, et al. Pathogen-induced inflammatory environment controls effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2011;187:4967–78. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marie JC, Liggitt D, Rudensky AY. Cellular mechanisms of fatal early-onset autoimmunity in mice with the T cell-specific targeting of transforming growth factor-beta receptor. Immunity. 2006;25:441–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas DA, Massague J. TGF-beta directly targets cytotoxic T cell functions during tumor evasion of immune surveillance. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:369–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, van der Most R, Ahmed R. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J Virol. 2003;77:4911–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4911-4927.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.