Abstract

Rationale

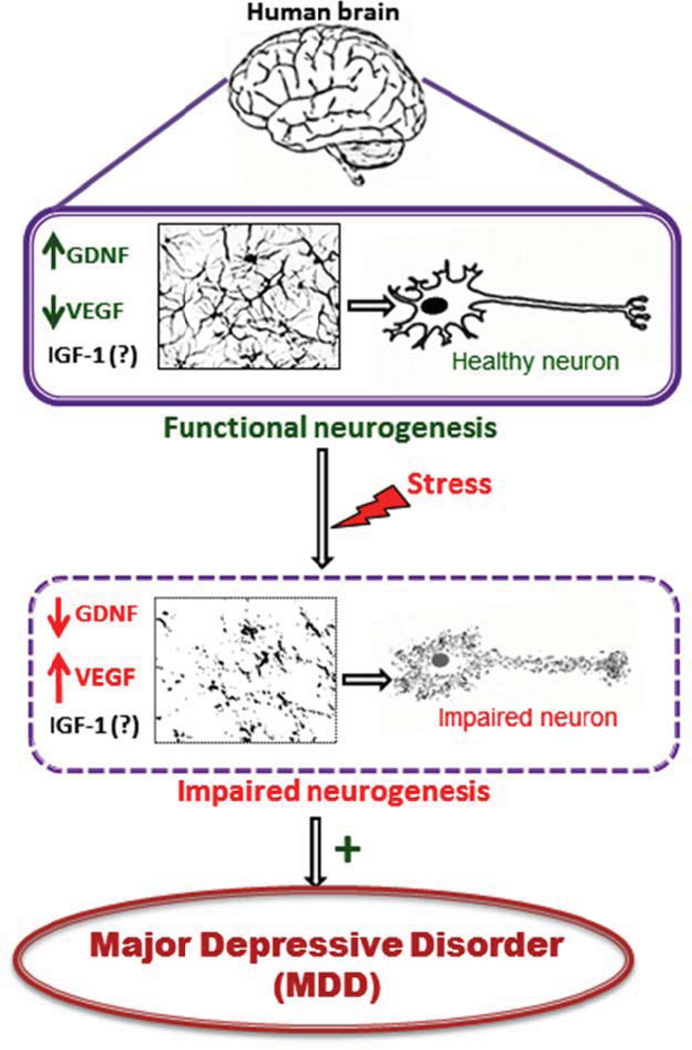

The neurotrophin hypothesis of major depressive disorder (MDD) postulates that this illness results from aberrant neurogenesis in brain regions that regulates emotion and memory. Notwithstanding this theory has primarily implicated BDNF in the neurobiology of MDD. Recent evidence suggests that other trophic factors namely GDNF, VEGF and IGF-1 may also be involved.

Purpose

The present review aimed to critically summarize evidence regarding changes in GDNF, IGF-1 and VEGF in individuals with MDD compared to healthy controls. In addition, we also evaluated the role of these mediators as potential treatment response biomarkers for MDD.

Methods

A comprehensive review of original studies studies measuring peripheral, central or mRNA levels of GDNF, IGF-1 or VEGF in patients with MDD was conducted. The PubMed/MEDLINE database was searched for peer-reviewed studies published in English through June 2nd, 2015.

Results

Most studies reported a reduction in peripheral GDNF and its mRNA levels in MDD patients versus controls. In contrast, IGF-1 levels in MDD patients compared to controls were discrepant across studies. Finally, most studies reported high peripheral VEGF levels and mRNA expression in MDD patients compared to healthy controls.

Conclusions

GDNF, IGF-1 and VEGF levels and their mRNA expression appear to be differentially altered in MDD patients compared to healthy individuals, indicating that these molecules might play an important role in the pathophysiology of depression and antidepressant action of therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Major depressive disorder, GDNF, IGF-1, VEGF, Neurorophin, Trophic factors, Biomarker

1. Introduction

The neurotrophin hypothesis of depression was initially formulated by Duman, Heninger, and Nestler(R. S. Duman, Heninger Gr Fau - Nestler, & Nestler, 1997). It postulated that MDD is secondary to aberrant neurogenesis in discrete brain regions subserving emotion and memory regulation1. According to this theoretical framework, stress-related alterations in BDNF signaling mediate aberrant neurogenesis in MDD. In addition, this theory indicates that antidepressants are efficacious because they increase BDNF expression, and thus resolve aberrant neuronal plasticity. Preclinical evidence allowing for mechanistic insights seems to fit well with these predictions. For example, Taliaz et al demonstrated that in rats a reduction in BDNF in the dentate gyrus impairs neurogenesis and induces depressive-like behaviors (Taliaz, Stall, Dar, & Zangen, 2010).

The neurotrophin theory is supported by studies demonstrating a decrease in BDNF in the postmortem brain of patients with MDD compared to non-depressed controls. Analyses of such post-mortem brains, that were harvested from depressed patients, found significant reduction in BDNF mRNA and protein levels in critical regions such as hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and amygdala (Dwivedi et al., 2003; Guilloux et al., 2012; Karege, Vaudan, Schwald, Perroud, & La Harpe, 2005). Interestingly, treatment with antidepressant medications was found to increase BDNF levels in the hippocampus, which further substantiated important role of this neurotrophin in MDD (Chen, Dowlatshahi, MacQueen, Wang, & Young, 2001). Blood levels of BDNF in MDD patients were also reported to be significantly low (Karege et al., 2002), which gets restored to normal after antidepressant treatment (H. Y. Lee & Kim, 2008). Recently, a large meta-analysis study indicated that peripheral BDNF levels are significantly lower in MDD patients compared to controls. In addition, antidepressant treatment increases peripheral BDNF levels in patients with MDD. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) also increases peripheral BDNF levels in MDD although the evidence is less compelling.

Thus, the biomedical literature is inundated with myriad of reports highlighting importance of BDNF in the MDD pathophysiology and treatment. In addition to BDNF’s role in the pathophysiology of MDD, other trophic factors may also contribute to neuroplasticity abnormalities in this disorder. For instance, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) were shown to contribute to maturation and maintenance of developing neurons, and modulate adult neurogenesis (Hoshaw, Malberg, & Lucki, 2005; Naumenko et al., 2013). The major objective of the present review is to compile and discuss comprehensively the role of these 3 trophic factors (i.e. GDNF, VEGF, and IGF-1) in MDD.

1.1. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)

GDNF is member of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily, and is broadly expressed in the mammalian brain. GDNF exerts its effects primarily through binding to GDNF-family receptors α1 (GFR α1) and activation of tyrosine kinase signaling4. GDNF is envisaged as a crucial factor for survival and maintenance of both dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons (P. Y. Lin & Tseng, 2015; Naumenko et al., 2013) due to its neuroprotective properties, particularly against oxidative and neuro-inflammatory damage. Additionally, the interplay between GDNF and dopaminergic pathways seems to be involved in memory and learning (Naumenko et al., 2013).

Preclinical evidence indicates that animals exposed to chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) - a model for depression, exhibit depression-like behavior, and decrease in GDNF expression in their hippocampus (Liu et al., 2012). Interestingly, chronic tricyclic antidepressant treatment helps to reverse depression-like behavior and restores hippocampal GDNF expression to normal (Liu et al., 2012).The role of GDNF in the pathophysiology of MDD has also been investigated in human studies. For example, studies that examined the serum, plasma and mRNA GDNF levels in MDD patients reported a significant reduction compared to healthy controls (P. Y. Lin & Tseng, 2015). A recent meta-analysis that evaluated GDNF changes in patients with depression strengthened this hypothesis (P. Y. Lin & Tseng, 2015). Thus, there seems to be a general trend for reduction in GDNF levels in MDD patients. However, there are few studies that reported increase in GDNF levels in the specific brain regions of MDD patients (Michel et al., 2008). For example, one post-mortem study reported an increase in GDNF levels in the parietal cortex of the MDD patients (Michel et al., 2008). Such discrepancy may be attributed to relatively smalls groups of MDD patients (n = 7) and healthy controls (n = 14) selected for this study.

1.2. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) is an endogenous peptide mainly produced in the liver, but also expressed in the brain. A pioneer study by Bach and colleagues (1991) examined IGF-1 mRNA expression in the rat brain starting from embryonic day 16 to postnatal day 82 (Bach, Shen-Orr, Lowe, Roberts, & LeRoith, 1991). It suggested that IGF-1 mRNA expression is regulated by the pre- and post-natal developmental time, especially in brain regions such as olfactory bulb, cerebral cortex, and hypothalamus (Bach et al., 1991). In contrast, IGF-1 mRNA expression in the brainstem and cerebellum remained constant throughout the study duration. Multiple effects have been attributed to IGF-1 in terms of its role in neuronal signaling, neurotrophic mechanisms, and neuroprotection in pro-neuroinflammatory conditions. These effects of IGF-1 are mediated by its binding to tyrosine kinase receptor (IGF-IR), which is structurally similar to the insulin receptor (Hoshaw et al., 2005; Szczesny et al., 2013). Due to its participation in neurogenesis, it has been theorized that imbalances in IGF-1 activity might be associated with the development of depression. For instance, clinical data suggests that peripheral IGF-1 levels are increased in depressed patients (Szczesny et al., 2013).

Interestingly, pre-clinical studies with rodents have demonstrated that IGF-1 may have antidepressant-like behavioral effects (Paslakis, Blum, & Deuschle, 2012; Szczesny et al., 2013). Central and peripheral administration of IGF-1 to rodents was shown to exhibit antidepressant-like effect (C. H. Duman et al., 2009; Hoshaw et al., 2005). In contrast to that, mice lacking IGF-1 gene, selectively in the hippocampal neurons, exhibit depression-like behavior (Michelson et al., 2000). Further, IGF-1 might have a significant role in the pathogenesis of BD, since its gene is located on a BD-associated chromosomal region. Additionally, its peripheral levels seem to be decreased in BD patients and up-regulated in lithium responsive patients (Scola & Andreazza, 2015). It will be interesting to examine if alterations in IGF-1 levels in BD patients are a universal phenomenon, or differ based on patients’ manic, depressive or euthymic status at the time of blood withdrawal. This may also help to understand why there is a reciprocal relationship between MDD (increased IGF-1) and BD (decreased IGF-1) in terms of their systemic IGF-1 levels.

1.3. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

VEGF is an angiogenic mitogen that belongs to the family of vasoactive growth factors. It exerts its characteristic molecular actions through the binding and activation of tyrosine kinase receptors present on endothelial cells. VEGF is classically associated with angiogenesis and vasculogenesis stimulation (Duric & Duman, 2013). However, recent evidence has indicated that it also affects neural cells and plays a significant role in hippocampal neurogenesis and neuroprotection (Clark-Raymond et al., 2014; Duric & Duman, 2013). Additionally, it is suggested to be involved in hippocampal processes, such as memory and learning (Clark-Raymond et al., 2014). Further, the relationship between stress-related conditions such as mood disorders and VEGF has been greatly explored over the last years (Newton, Fournier, & Duman, 2013). The role of VEGF in neurogenesis appears to be pivotal in the pathogenesis of MDD. Its signaling also seems to be significantly modified by the action of antidepressant medications and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which indicates that the regulation of VEGF mechanisms might be partially responsible for the behavioral effects observed with these treatments (Nowacka & Obuchowicz, 2012; Warner-Schmidt & Duman, 2008). In addition, cerebral endothelial dysfunction, caused by cerebrovascular diseases has been associated with a higher incidence of depression. Thus, VEGF could potentially be a molecular link between these conditions (Nowacka & Obuchowicz, 2012; Warner-Schmidt & Duman, 2008). VEGF may also be involved in the pathogenesis of BD as well. For instance, there is a phasic alteration in VEGF levels in BD, being usually high in maniac and depressive stages. It has also been noticed that lithium treatment apparently decreases VEGF expression in remissive patients (Scola & Andreazza, 2015). This may hint towards the role of VEGF in pharmacological effects of mood stabilizers such as lithium.

Although, there are handful of studies, as listed above (under section 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3), proposing role of GDNF, IGF-1 and VEGF in mood disorders such as MDD and BD, there are no attempts till date to comprehensively review their role and their potential interplay in the pathophysiology of MDD and impact of pharmacological interventions on them in MDD patients. Intrigued with above-cited reports, the aim of the present review was to critically summarize evidence regarding changes in GDNF, IGF-1 and VEGF in depressed patients and how these neurotrophic factors might be affected by antidepressant medication. Our main focus was to assess available and relevant clinical studies on these topics, discussing their limitations and proposing directions for further research.

1.4. Review objectives

The neurotrophin hypothesis for MDD is based on the notion that aberrations in the neurogenetic mechanisms in selective brain regions, specifically those regulating memory and emotions, are responsible for MDD. Hitherto, the neurotrophin hypothesis for MDD is primarily based on studies implicating aberrations in BDNF signaling. However, there is a need to comprehensively review the role of other trophic factors such as GDNF, IGF-1 and VEGF in MDD. Thus, the present review was aimed to critically summarize evidence regarding changes in GDNF, IGF-1 and VEGF in individuals with MDD compared to healthy controls. In addition, we also evaluated the role of these mediators as potential treatment response biomarkers for MDD.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

The PubMed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) from the National Library of Medicine (NLM) was searched through June 2nd, 2015. The Boolean terms that were used are: "Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor" OR "Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Receptors" OR "Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factors" OR "Insulin-Like Growth Factor I" OR "Receptor, IGF Type 1" OR "Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A" OR "Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor B" OR "Insulin-Like Growth Factor II" OR "Receptor, IGF Type 2" OR “GDNF” OR “VEGF” OR “IGF-1” OR “IGF-2” AND "Depression" OR "Depressive Disorder" OR “depression” OR “antidepressant”. A reference management software (EndNote X7 for Windows, Thomson Reuters 2013) was used for literature search and screening purposes. Only original, peer-reviewed English language articles were considered for inclusion in this review.

The PubMed search resulted in 566 studies, published from 1986 to June, 2015. The titles and abstracts of retrieved articles were screened in order to determine if they were potentially eligible for inclusion. We included studies that: (1) measured GDNF, IGF-1 or VEGF protein level in the blood, plasma, serum, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and brain homogenates as well as those that assessed mRNA expression and genotyping of these neurotrophins; and (2) had study participants diagnosed with depression. Studies that were selected for inclusion employed clinical diagnosis of study participants through a validated structured diagnostic interview instrument according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) criteria. Pre-clinical studies, case reports, and interventional studies employing treatments other than antidepressants, and reviews were excluded.

440 articles were discarded since they did not meet inclusion criteria. The full texts of the remaining articles were retrieved and examined. From the 126 studies considered for inclusion, 83 were excluded because they were reviews (n=17), pre-clinical studies (n=45), or evaluated interventions other than antidepressants (n=21). Forty-three references were included in this review.

2.2. Data extraction

The data that were extracted from the primary studies and included in this review are: (1) country of study origin; (2) measurement types, including levels of neurotrophin in serum, plasma, whole blood, cerebrospinal fluid or brain homogenates, as well as mRNA expression and genotyping; (3) the population evaluated by the study; (4) sample size discriminated by the number of cases and controls, if any; (5) mean age of cases and controls, if any; (6) percentage of females in case and control groups, if any; (7) depression instrument used, if any; (8) depression severity, determined by the mean score obtained from depression instrument; (9) neurotrophin changes in cases compared to controls, if any; and (10) antidepressant use and its effect on neurotrophins, if any.

3. Results

The characteristics of all 43 studies included in this review are summarized in tables 1, 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Summary of GDNF clinical studies in major depressive disorder (MDD)

| Reference | Country | Measurement | Patient population |

Sample size (case/control) |

Mean age (case/control) |

%Female (case/control) |

Depression instrument |

Depression severity (Mean ± SD) |

GDNF in depressed vs. controls |

Antidepressant use and its effect in GDNF, if any |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al., 2014 | China | Serum | MDD | 32/32 | 46.2 ± 16.0/40.3± 10.8 |

46.9/56.2 | HDRS | 25.4 ±6.2 | ↓ (p < 0.001) |

No |

| Tseng et al., 2013 | Taiwan | Serum | MDD | 55 (29 severe, 26 remitted)/35 |

Severe: 45.8±11.6, Remitted:46.4±14.0/4 8.3±10.7 |

Severe: 62.1, Remitted:53.8/ 57.1 |

HDRS | Severe:25.2±4.9 /Remitted: 3.0±2.2 |

↓ (p < 0.001) |

Yes, Imipramine equivalent |

| Pallavi et al., 2013 | India | Serum | Adolescent MDD |

84/64 | 15.5± 1.8/15.4±1.7 | 33.3/54.6 | BDI-II | 30(10,60)* | ↓ (p < 0.001) |

Yes, SSRI |

| Diniz et al., 2012 | Brazil | Serum | Late-life MDD |

34/37 | 69.7±4.5/67.8 ±5.4 | 73.5/78.3 | HDRS | 19.1 ± 6.8 | ↓ (p < 0.001) |

No |

| Wang et al., 2011 | China | Plasma | Late-life MDD |

27/28 | 67.85±5.63/65.32±8.0 7 |

59.2/57.1 | HDRS | 31.3±4.58 | ↑ (p<0.05) |

Yes, not specified |

| Zhang et al., 2008 | China | Serum | MDD | 76/50 | 45.1±14.7/43.4±13.4 | 55.3/56.0 | HDRS | 28.6±7.9 | ↓ (p < 0.001) |

Yes, SSRI/SNRI. ↑ in GDNF (p<0.001) |

| Otsuki et al., 2008 | Japan | mRNA | MDD, BD | 60 MDD (40 remissive), 42 BD(13 depressive)** |

MDD: 52.3 ±3.5, Depressive BD: 55.5 ± 3.5** |

MDD: 50, Depressive BD: 84.6** |

HDRS | MDD:25.9±1.9/BD depressive:24.6 ± 1.1 |

↓ expression (p<0.01)**¥ |

Yes, not specified |

| Michel et al., 2008 | Germany | Brain homogenates |

Recurrent MDD (Post- Mortem) |

7/14 | 85.71±4.79/79.60±7.7 4 (Age of death) |

71.4/42.8 | - | - | ↑ in parietal cortex (p = 0.0262) |

Yes, SSRI/TCA |

| Takebayashi et al., 2006 | Japan | Whole blood | MDD, BD | 56(39 MDD, 17 BD)/56 |

MDD:60.0±13.0, BD: 56.9 ±11.2/47.5 ±9.41 |

MDD:66.6, BD:76.4/69.6 |

- | - | ↓ (p = 0.0003) |

Yes, not specified |

Median (Range).

No control group.

MDD patients in current depressive state vs. those in remissive state.

BD: Bipolar disorder, HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory II, SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, SNRI: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, TCA: Tricyclic antidepressants.

Table 2.

Summary of IGF-1 clinical studies in major depressive disorder (MDD)

| Reference | Country | Measurement | Patient population |

Sample size (case/control) |

Mean age (case/control) |

%Female (case/control) |

Depression instrument |

Depression severity (Mean ± SD) |

IGF-1 in depressed vs. controls |

Antidepressant use and its effect in IGF-1, if any |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| van Varsseveld et al., 2015 | Netherlands | Serum | Late-life MDD |

1188 (Minor DD: 161/MDD:32; No DD:995)** |

75.4 ±6.5** | 50.33** | CES-D | - |

Females 3y FW: ↓ DD probability in ↓IGF-l (OR=0.43)** |

Yes, not specified |

| Kopczak et al., 2015 | Germany | Serum | MDD | 78/92 | 48.64±13.88/ 48.13±13.70 |

44.87/45.65 | HDRS | 26.37±6.73 | ↑ (p = 3.29E-04) |

Yes, not specified. IGF-1 still increased after 6 wk Rx (p=0.002) |

| Sievers et al., 2014 | Germany | Serum | West Pomerania Cohort* |

4079 (1246 had depressive symptoms )** |

50.0 ±16.4** | 51** | WHO WMH-CIDI |

- |

Females: ↑ DD probability in ↓ IGF-1 (OR=2.39). Males: ↑ DD probability in ↑ IGF-1 (OR=3.03)** |

No |

| Lin et al., 2014 | USA | Plasma | Adults age ≥50* |

94** | 60.68 ±8.42** | 58.5** | GDS | Stronger association between depression and cognition in ↑lGF-1** |

Yes, not specified | |

| Emeny et al., 2014 | Germany | Serum | KORA-Age study cohort* |

985 (144 had depressive symptoms)** |

Men:75.4 (74.9- 76.0), Women:75.7 (75.1–76.3)**¥ |

50** | GDS | - |

Females: IGF-1 positively associated with depression (p = 0.045)** |

No |

| Weber-Hamann et al., 2009 | Germany | Serum | MDD | 77 (34 on Amitriptyline, 43 on Paroxetine)** |

Amitriptyline (R:51 ± 17,NR:46± 16),Paroxetine (R:58 ±169,NR:57±14)** |

Amitriptyline (R:72,NR:88.8), Paroxetine (R:62.9,NR:75)** |

HDRS | Amitriptyline (R:23.9± 5.2,NR:22.1±3.9) Paroxetine (R:23.0 ±3.2,NR:23.7±3.5) |

Yes, Amitriptyline and Paroxetine. ↓UGF-l in R (p<0.02) |

|

| Rueda Alfaro et al., 2008 | Spain | Plasma | Adults age >70* |

313 (100 had depressive symptoms )** |

Men:76.7±5.4, Women:77.3±6.4** |

51.11** | GDS | - |

Females: IGF-1 positively associated with cognition, after adjustment for depression (p = 0.04)** |

No |

| Michelson et al., 2000 | USA | Plasma | MDD | 107 (37 on Fluoxetine, 34 on Sertraline-36 on Paroxetine)** |

Fluoxetine: 40.0±11.4, Sertraline:38.7±14.5, Paroxetine: 39.9±1.11** |

Fluoxetine:75.7, Sertraline: 76.5, Paroxetine:61.1** |

HDRS | Fluoxetine:4.8±2.4, Sertraline:4.7±2.3, Paroxetine:4.9 ±2.8 |

- | Yes, Fluoxetine, Sertraline, Paroxetine. Placebo substitution of Paroxetine resulted in -↑ IGF-1 (p=0.007) |

| Franz et al., 1999 | USA | Serum | MDD | 19/16 | 34.7 ±8.8/36.1 ±6.6 | 100/100 | HDRS | 18.8±3.9 | ↑ (p = 0.07) |

No |

| Deuschle et al., 1997 | Germany | Plasma | MDD | 24/33 | Male:46±16,Female: 48±18/Male:53± 18,Female:25±2 |

45.83/33.33 | HDRS | Young:31.6±5.0, Old:31.9±6.7 |

↑ (p<.01) |

Yes, Fluoxetine, Amitriptyline, Doxepin. IGF-1 decreased in R (p< 0.04) |

| Lesch et al., 1988 | Germany | Plasma | MDD,BD | 34 (6 patients also had BD)/34 |

48.2±12.2/44.7±11.9 | 67.64/67.64 | HDRS | 26.95±5.4 | ↑ (p < 0.001) |

No |

Evaluated for depressive symptoms.

No control group.

Median (Range)

BD: Bipolar disorder, DD: Depression disorder, R: Responders, NR: Non-responders, CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, WHO WMH-CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview, GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale, FW: Follow-up, DD, OR: Odds ratio, Rx: Treatment.

Table 3.

Summary of VEGF clinical studies in major depressive disorder (MDD)

| population | (case/control) | (case/control) | (case/control) | instrument | severity (Mean ± SD) |

depressed vs. controls |

effect in VEGF, if any | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elfving et al., 2014 | Denmark | Serum and Genotyping |

MDD | 155/280 | 46.8 ± 9.5/ 45.8±10.4 |

84/80 | WHO SCAN | ↑ (p=0.0001) VEGF 1612G/A (rsl0434) is associated with MDD (p = 0.002) |

Yes, not specified |

|

| Clark-Raymond et al., 2014 | USA | Plasma | MDD | 66/21 | 41.3±12.2/ 38.9±11.8 |

63.6/66.7 | HDRS, BDI | - | ↑ (p = 0.001) | No |

| Carvalho et al., 2014 | Netherlands | Serum | MDD | 47/42 | 54 (32–82)/ 49 (3131–74)¥ |

57/50 | HDRS | 24.4(18–30)¥ | ↑ (p = 0.028) | No |

| Berent et al., 2014 | Poland | Serum and mRNA |

MDD | 38/38 | 51.29 ±11.55/ 33.11 ±9.51 |

47.37/65.79 | HDRS | 18.95 ± 5.90 | ↑ Serum VEGF (p <0.001) ↑ mRNA expression (p = 0.001) |

Yes, Fluoxetine, Sertraline, Citalopram |

| Shibata et al., 2013 | Japan | mRNA | MDD, BD | 59 MDD (39 remissive), 44 BD (12 depressive)/28 |

MDD:52.3±3.6 depressive), Depressive BD: 54.8±3.9/50.0±1.8 |

MDD:57.62 BD:79.54/46.42 |

HDRS | MDD:25.9±1.9, Depressive BD: 24.5±1.2 |

↑ mRNA expression (p<0.01) |

Yes, not Specified. |

| Halmai et al., 2013 | Hungary | Plasma | MDD, BD | 34(21 MDD, 13 BD)** |

R:46.0±12.5, NR:41.6±12.9** |

R: 69.56, NR:81.81** |

MADRS | R:35.5±1.5, NR:36.0±1.7 (Before Rx) |

↑ VEGFin NRvs. R (p = 0.055)** |

Yes, not specified |

| Galecki and Orzechowska et al., 2013 | Poland | mRNAand Genotyping |

Recurrent MDD |

268/200 | 45.5±9.98/ 37.1±7.84 |

56.7/60.5 | HDRS | ↑ KDR mRNAand protein expression in rDD patients ( p<0.001) |

||

| Galecki and Galecka et al., 2013 | Poland | Serum, mRNA, Genotyping |

Recurrent MDD |

268/200 | 45.5 ± 9.98/ 37.1 ±7.84 |

56.7/60.5 | HDRS | ↑Serum levels (p = 0.019) ↑ mRNA expression (p = 0.002) ↑ VEGF 405G/C |

||

| Fornaro et al., 2013 | Italy | Plasma | MDD | 30/32 | 48.27±9.674/ 45.23±11.623 |

80/75 | HDRS | 21.60±3.747 | At baseline, there was no difference |

Yes, Duloxetine. Among R, VEGF ↑ after 6wks of Rx (p=0.006). Among NR. VEGF ↓ after 12wks of Rx (p=0.000) |

| Carvalho et al., 2013 | UK | Serum | MDD | 19 (R:6, NR:14)/21 | R:47.2±3.0, NR:50.9±3.6/ 45.9±2.4 |

73.68 (R:50, NR:78.57)/71.42 |

HDRS, BDI | HDRS: R:21.8±1.9, NR:21.7±2.1/ BDI: R:32.7±3.7, NR:37.6±3.6 |

↓ (p=0.047) | No |

| Lee et al., 2012 | Korea | Plasma | MDD, BD | 35 MDD, 35 BD/60 | MDD: 29.8±7.1, BD:33.7±7.4/ 33.0±7.0 |

MDD:65.71, BD:62.85/55 |

HDRS | 22.1±6.7 | ↑ (p=0.023) | No |

| Kotan et al., 2012 | Turkey | Serum | Melancholic MDD |

40/40 | 35 ± 8/34 ± 8 | 80/80 | HDRS | 31.1 ±3.2 | There was no difference |

No |

| Isung and Mobarrez et al., 2012 | Sweden | Plasma | Suicide attempters |

58** | Men:39±12.7/ Women:36±12** |

60.34** | MADRS | Surviving: 17 (10–23), Victims:12.1 (3–21)¥ |

↓ among victims (p = 0.033)** |

Yes, SSRI |

| Isung and Aeinehband et al., 2012 | Sweden | CSF | Suicide attempters |

43** | 45±12.8** | 65.11** | MADRS | - | ↓ among attempters (p = 0.0004)** |

No |

| Dome et al., 2012 | Hungary | Plasma | MDD | 24** | 42.7±12.1** | 79.16** | MADRS | 35.4±7.2 (Before Rx) |

- | Yes, SSRI, SNRI, Other. ↑VEGF after Rx was not statistically significant |

| Arnold et al., 2012 | USA | Plasma | ADNI cohort* |

566 (165 had depressive symptoms)** |

74.8±7.5** | 62** | 6DS | 1.0 ±1.2 (All cohort) |

Associated with depressive symptoms (p = 0.0264)** |

- |

| Viikki et al., 2010 | Finland | Genotyping | Rx resistant MDD |

217 ( ECTRx:119, SSRI Rx: 98)/394 |

ECT Rx: 57.7±14.0, SSRI Rx: 40.7±13.9 /44.4±11.1 |

43.31 (ECT Rx:45.4, SSRI Rx: 40.8)/45.7 |

MADRS | ECT Rx:32.5±8.2, SSRI Rx:27.0±5.7 |

VEGF 2578 C/A associated with Rx resistant MDD (p = 0.015) |

Yes, Citalopram, Fluoxetine, Paroxetine |

| Takebayashi et al., 2010 | Japan | Plasma | MDD | 16/16 | 53.2 ± 13.0/ 53.8 ±12.5 |

50/50 | - | - | ↑ (p = 0.05) | Yes, SSRIJCA |

| Ventriglia et al., 2009 | Italy | Serum | MDD | 25/30 | 43.36±9.97/ 41.57±8.26 |

80/83.33 | HDRS | 19.68±2.76 | There was no difference |

Yes, Escitalopram |

| Tsai et al., 2009 | Taiwan | Genotyping | MDD | 351** | 43.7±15.7** | 58.68** | HDRS | R:28.5±5.0, NR:29.3±5.0 |

VEGF genetic variants were not associated with antidepressant therapeutic effect** |

Yes, Fluoxetine, Citalopram |

| Kahl et al., 2009 | Germany | Serum | MDD,BD | 12 (MDD + BD)/12 | 26.3 ±5.1/ 25.6 ±3.9 |

100/100 | BDI | 34.9 ±8.3 (MDD,BD) |

↑ (p = 0.01) | No |

| Dome et al., 2009 | Hungary | Plasma | MDD | 33/16 | 40.6±10.6/ 40.3±9.5 |

88/88 | BDI | 38.6±10.7 | ↓ (p = 0.1) | Yes, SSRI, SNRI, Other |

| Iga et al., 2007 | Japan | mRNA and Genotyping |

MDD | 32/32 | 42.7±12.6/ age matched |

68.75/ sex mate |

HDRS | - | ↑mRNA expression (p=0.023) VEGF 2578 C/A and VEGF634G/C are not associated with depression |

Yes, Paroxetine |

Evaluated for depressive symptoms.

No control group.

Median (Range)

CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid, BD: Bipolar disorder, Rx: Treatment, R: Responders, NR: Non-responders, ECT: Electroconvulsive therapy, SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, WHO-SCAN: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry, HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, MADRS: Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale, GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale, rDD: Recurrent depressive disorder, TCA: Tricyclic antidepressants.

3.1. GDNF and Major Depressive Disorder

Table 1 presents a summary of GDNF studies in patients with MDD. 9 articles (Diniz et al., 2012; Michel et al., 2008; Otsuki et al., 2008; Pallavi et al., 2013; van Varsseveld et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2008) published from 2006 to 2014, are listed. Three studies were performed in China (Wang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2008) and two in Japan (Otsuki et al., 2008; Takebayashi et al., 2006). The last four were conducted in four different countries (Taiwan (Tseng, Lee, & Lin, 2013), India (Pallavi et al., 2013), Brazil (Diniz et al., 2012) and Germany (Michel et al., 2008). Five studies measured GDNF serum levels (Diniz et al., 2012; Pallavi et al., 2013; Tseng et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2008), one measured GDNF plasma levels (Wang et al., 2011), and one evaluated GDNF whole blood levels (Takebayashi et al., 2006). While a study by Otsuki and colleagues was the only study that measured mRNA expression (Otsuki et al., 2008), Michel and co-workers performed a post-mortem assessment of GDNF levels in homogenates of different regions of the brain (Michel et al., 2008). Regarding the patient population included, only two studies evaluated MDD and BD patients simultaneously (Otsuki et al., 2008; Takebayashi et al., 2006). In contrast to that, the remaining articles were restricted to studies on depressed patients. Most populations evaluated in these studies were either middle aged (Otsuki et al., 2008; Tseng et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2008), or elderly (Diniz et al., 2012; Michel et al., 2008; Takebayashi et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2011). Only one study assessed patients with mean age ≤ 40 years (Pallavi et al., 2013). With the exception of studies by Zhang and co-workers (Zhang et al., 2014) and Pallavi and co-workers (Pallavi et al., 2013), in all studies females comprised more than 50% of cases, and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) was the preferred depression instrument.

In six different studies, GDNF levels were found to be decreased in depressed patients compared to controls (Diniz et al., 2012; Pallavi et al., 2013; Takebayashi et al., 2006; Tseng et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2008). Additionally, Otsuki and colleagues showed that GDNF mRNA expression was decreased in depressed patients (Otsuki et al., 2008). Only two studies demonstrated opposite results (Michel et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Wang and colleagues found increased GDNF plasma levels in cases versus controls (Wang et al., 2011), while Michel and co-workers reported increased GDNF levels in the parietal cortex homogenates of deceased depressed patients compared to post-mortem controls (Michel et al., 2008).

At the time of evaluation, most patients were on antidepressant treatment. In addition, Zhang and co-workers found that the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) or serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) was associated with a statistically significant increase in GDNF serum levels (Zhang et al., 2008).

3.2. IGF-1 and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

Table 2 presents a summary of studies that examined IGF-1 in MDD patients. Eleven articles, published from 1988 to 2015 were included (Deuschle et al., 1997; Emeny et al., 2014; Franz et al., 1999; Kopczak et al., 2015; Lesch, Rupprecht, Muller, Pfuller, & Beckmann, 1988; F. Lin, Suhr, Diebold, & Heffner, 2014; Michelson et al., 2000; Rueda Alfaro et al., 2008; Sievers et al., 2014; van Varsseveld et al., 2015; Weber-Hamann et al., 2009). Six studies were conducted in Germany (Deuschle et al., 1997; Emeny et al., 2014; Kopczak et al., 2015; Lesch et al., 1988; Sievers et al., 2014; Weber-Hamann et al., 2009), and three in the US (Franz et al., 1999; F. Lin et al., 2014; Michelson et al., 2000). The remaining two studies were performed in the Netherlands (van Varsseveld et al., 2015) and Spain (Rueda Alfaro et al., 2008). While six studies measured IGF-1 serum levels (Emeny et al., 2014; Franz et al., 1999; Kopczak et al., 2015; Rueda Alfaro et al., 2008; Sievers et al., 2014; van Varsseveld et al., 2015), five assessed IGF-1 plasma levels (Deuschle et al., 1997; Lesch et al., 1988; F. Lin et al., 2014; Michelson et al., 2000; Rueda Alfaro et al., 2008). In six studies, the study population consisted exclusively of MDD patients (Deuschle et al., 1997; Kopczak et al., 2015; Michelson et al., 2000; van Varsseveld et al., 2015; Weber-Hamann et al., 2009). Additionally, one study evaluated MDD and BD populations at the same time (Lesch et al., 1988)37. Two studies included large cohorts of patients evaluated for depressive symptoms (Emeny et al., 2014; Sievers et al., 2014); and two studies assessed depression in individuals at certain age ranges. Only middle aged (Deuschle et al., 1997; Franz et al., 1999; Kopczak et al., 2015; Lesch et al., 1988; Michelson et al., 2000; Sievers et al., 2014; Weber-Hamann et al., 2009) and elderly (Emeny et al., 2014; F. Lin et al., 2014; Rueda Alfaro et al., 2008; van Varsseveld et al., 2015) populations were evaluated in these articles and females comprised more than 50% of cases in most of these studies. Regarding depression instruments, HDRS was used in six studies (Deuschle et al., 1997; Franz et al., 1999; Kopczak et al., 2015; Lesch et al., 1988; Michelson et al., 2000; Weber-Hamann et al., 2009) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used in three of them (Emeny et al., 2014; F. Lin et al., 2014; Rueda Alfaro et al., 2008). Different depression instruments were utilized in the remaining articles (Sievers et al., 2014; van Varsseveld et al., 2015).

IGF-1 levels were found to be increased in depressed patients compared to controls in four studies (Deuschle et al., 1997; Franz et al., 1999; Kopczak et al., 2015; Lesch et al., 1988). Two of themevaluated plasma samples (Deuschle et al., 1997; Franz et al., 1999), and the other two assessed serum specimen (Franz et al., 1999; Kopczak et al., 2015). Van Varsseveld and co-workers demonstrated a decrease in the probability of depression among females with low IGF-1 levels after a 3 year-follow-up (van Varsseveld et al., 2015). In contrast, Sievers and colleagues described an increase in the odds of depression among females with low IGF-1 levels (Sievers et al., 2014). In males, an increase in the probability of depression was observed among those with high IGF-1 levels (F. Lin et al., 2014). Further, Lin and co-workers reported a strong association between depression and cognition in patients with high IGF-1 levels. Moreover, one study found a positive association between depression and IGF-1 levels in females (Emeny et al., 2014). And, finally another study reported that, after adjustment for depression, among females IGF-1 was positively associated with cognition, (Rueda Alfaro et al., 2008).

Patients from six of these studies were using antidepressants at the time of evaluation (Deuschle et al., 1997; Kopczak et al., 2015; F. Lin et al., 2014; Michelson et al., 2000; van Varsseveld et al., 2015; Weber-Hamann et al., 2009). Weber-Hamann and colleagues demonstrated that the use of antidepressants: amitriptyline and paroxetine was associated with a significant decrease in IGF-1 plasma levels (Weber-Hamann et al., 2009). Further, Michelson and colleagues found that the placebo substitution of paroxetine resulted in a significant increase in IGF-1 plasma levels (Michelson et al., 2000). In addition, Deuschle and co-workers reported a significant decrease in IGF-1 plasma levels in patients responding to antidepressant therapy (Deuschle et al., 1997).

3.3. VEGF and Major Depressive Disorder

Twenty-three articles published between 2007 and 2014 that studied VEGF in MDD patients are summarized in Table-3 (Arnold et al., 2012; Berent, Macander, Szemraj, Orzechowska, & Galecki, 2014; L. A. Carvalho et al., 2014; L. A. Carvalho et al., 2013; Clark-Raymond et al., 2014; Dome et al., 2012; Dome et al., 2009; Elfving et al., 2014; Fornaro et al., 2013; Galecki, Galecka, et al., 2013; Galecki, Orzechowska, et al., 2013; Halmai et al., 2013; Iga et al., 2007; Isung, Aeinehband, et al., 2012; Isung, Mobarrez, Nordstrom, Asberg, & Jokinen, 2012; Kahl et al., 2009; Kotan, Sarandol, Kirhan, Ozkaya, & Kirli, 2012; B. H. Lee & Kim, 2012; Shibata et al., 2013; Takebayashi, Hashimoto, Hisaoka, Tsuchioka, & Kunugi, 2010; Tsai et al., 2009; Ventriglia et al., 2009; Viikki et al., 2010). Researchers from Japan (Iga et al., 2007; Shibata et al., 2013; Takebayashi et al., 2010), Poland (Berent et al., 2014; Galecki, Galecka, et al., 2013; Galecki, Orzechowska, et al., 2013) and Hungary (Dome et al., 2012; Dome et al., 2009; Halmai et al., 2013) performed three studies each. While USA (Arnold et al., 2012; Clark-Raymond et al., 2014), Italy (Fornaro et al., 2013; Isung, Aeinehband, et al., 2012), and Sweden (Isung, Aeinehband, et al., 2012; Isung, Mobarrez, et al., 2012) researchers conducted two studies each. Moreover, Denmark (Elfving et al., 2014), the Netherlands (L. A. Carvalho et al., 2014), the United Kingdom (UK) (L. A. Carvalho et al., 2013), Korea (B. H. Lee & Kim, 2012), Turkey (Kotan et al., 2012), Finland (Viikki et al., 2010), Taiwan (Tsai et al., 2009) and Germany (Kahl et al., 2009) scientists contributed to one of these studies each. Nine studies measured VEGF plasma levels (Arnold et al., 2012; Clark-Raymond et al., 2014; Dome et al., 2012; Dome et al., 2009; Fornaro et al., 2013; Halmai et al., 2013; Isung, Aeinehband, et al., 2012; B. H. Lee & Kim, 2012; Takebayashi et al., 2010); and eight assessed its serum levels (Berent et al., 2014; A. F. Carvalho et al., 2015; L. A. Carvalho et al., 2014; Elfving et al., 2014; Galecki, Galecka, et al., 2013; Kahl et al., 2009; Kotan et al., 2012; Ventriglia et al., 2009). Additionally, five studies evaluated mRNA expression (Berent et al., 2014; Galecki, Galecka, et al., 2013; Galecki, Orzechowska, et al., 2013; Iga et al., 2007; Shibata et al., 2013), and six assessed genotyping (Elfving et al., 2014; Galecki, Galecka, et al., 2013; Galecki, Orzechowska, et al., 2013; Iga et al., 2007; Tsai et al., 2009; Viikki et al., 2010). Only one study measured VEGF levels in the CSF (Isung, Mobarrez, et al., 2012). Sixteen studies exclusively evaluated MDD patients (Berent et al., 2014; L. A. Carvalho et al., 2014; L. A. Carvalho et al., 2013; Clark-Raymond et al., 2014; Dome et al., 2012; Dome et al., 2009; Elfving et al., 2014; Fornaro et al., 2013; Galecki, Galecka, et al., 2013; Galecki, Orzechowska, et al., 2013; Iga et al., 2007; Kotan et al., 2012; Takebayashi et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2009; Ventriglia et al., 2009; Viikki et al., 2010), and four assessed MDD and BD populations simultaneously (Halmai et al., 2013; Kahl et al., 2009; B. H. Lee & Kim, 2012; Shibata et al., 2013). Two articles studied populations of suicide attempters (Isung, Aeinehband, et al., 2012; Isung, Mobarrez, et al., 2012), and one included a large cohort of depression patients (Arnold et al., 2012). Elderly populations were majorly studied in these articles, and females were more than 50% of cases in all except three studies (Berent et al., 2014; Takebayashi et al., 2010; Viikki et al., 2010). HDRS was the most commonly used depression instruments.

VEGF levels were increased in the plasma or serum of depressed patients versus controls in eight studies (Berent et al., 2014; L. A. Carvalho et al., 2014; Clark-Raymond et al., 2014; Elfving et al., 2014; Galecki, Galecka, et al., 2013; Kahl et al., 2009; B. H. Lee & Kim, 2012; Takebayashi et al., 2010). On the other hand, two studies (L. A. Carvalho et al., 2013; Dome et al., 2009) demonstrated decreased plasma or serum VEGF levels in depressed patients compared to healthy individuals. No significant difference in VEGF levels between cases and controls were reported in three studies (Fornaro et al., 2013; Kotan et al., 2012; Ventriglia et al., 2009). Additionally, four articles (Berent et al., 2014; Galecki, Galecka, et al., 2013; Halmai et al., 2013; Iga et al., 2007) found increased mRNA expression levels in MDD patients in comparison with controls, Halmai et al described increased plasma VEGF levels in depressed patients that did not respond to antidepressant therapy versus those that responded (Halmai et al., 2013). Moreover, Arnold et al reported a statically significant association between depressive symptoms and VEGF plasma levels(Arnold et al., 2012).

Among suicidal individuals, VEGF was found to be decreased in the plasma of victims (Isung, Mobarrez, et al., 2012) and in the CSF of attempters (Isung, Aeinehband, et al., 2012). Regarding VEGF polymorphisms, Elfving and colleagues pointed out that the VEGF 1612G/A (rs10434) was significantly associated with depression (Elfving et al., 2014). On the other hand Galecki and Galecka reported that VEGF 405G/C was increased in depressed patients compared to controls (Galecki, Galecka, et al., 2013). Moreover, Viikki and colleagues suggested that VEGF 2578 C/A was associated with treatment resistant MDD (Viikki et al., 2010). In contrast, some studies suggested that VEGF genetic variations were not associated with depression or antidepressant therapeutic effect (Iga et al., 2007).

Patients from thirteen of these studies were being treated with antidepressants at the time of evaluation (Berent et al., 2014; Dome et al., 2012; Dome et al., 2009; Elfving et al., 2014; Fornaro et al., 2013; Halmai et al., 2013; Iga et al., 2007; Isung, Mobarrez, et al., 2012; Takebayashi et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2009; Ventriglia et al., 2009; Viikki et al., 2010). Fornaro and colleagues found that VEGF plasma levels increased after six weeks of duloxetine treatment among respondent patients (Fornaro et al., 2013). Besides, VEGF levels were decreased after twelve weeks of therapy in patients that did not clinically respond to treatment. Dome and colleagues also reported an increase in VEGF plasma levels after antidepressant use, but it was not statistically significant (Dome et al., 2012).

4. Discussion

The principal findings of the present review are: (i) when compared with healthy individuals, MDD patients experience differential alterations in their systemic neurotrophins levels and their mRNA expression; and (ii) the balance of such neurotrophin alterations in MDD patients is tilted in such a manner that there is a significant decrease in GDNF and IGF-1 levels as well as increase in VEGF levels. These findings supports the neurotrophic hypothesis of depression1- a novel and increasingly important theory that aims to expand current understanding pertaining to underlying mechanisms for MDD pathophysiology.

Since half of the twentieth century, dysregulations in classic monoaminergic signaling were considered to be major pathophysiologic mechanisms for depression. All currently prescribed antidepressant medications are thought to modulate monoamine metabolism in order to promote positive behavioral outcomes (Walker, 2013). However, these medications come with a price-tag such as treatment refractoriness and myriad of undesired effects. These limitations put a question-mark on whether the monoamine theory provides a complete neurobiological explanation of depression (Hoshaw et al., 2005; Paslakis et al., 2012; Walker, 2013). Thus, alternative hypotheses such as neurotrophic changes in MDD patients are gradually been conceptualized as a viable potential mechanism for the pharmacological management of depression (Hoshaw et al., 2005; Paslakis et al., 2012). The findings based on studies summarized in this review corroborate with this hypothesis. It also helps to shed some light on how antidepressant drugs may possibly exert their beneficial effects by their significant influence on distinct neurotrophins.

4.1. Lower GDNF levels in Major Depressive Disorder

The vast majority of studies assessing GDNF alterations in MDD found that serum, plasma and mRNA expression levels were decreased in these patients when compared with healthy controls. These findings also corroborated with a recent meta-analysis that evaluated GDNF changes in patients with depression, including those with concomitant bipolar disease (P. Y. Lin & Tseng, 2015). However, there are some conflicting reports as well regarding GDNF changes among patients with MDD and BD (P. Y. Lin & Tseng, 2015). For example, one study reported that the serum levels of this neurotrophin were significantly increased in depressed bipolar patients (Rosa et al., 2006). While another study reported exact opposite outcomes (Zhang et al., 2010). Despite the similarities, discrepancies in the results were also observed. The lack of consistency in the data might be because of different sample sources, diagnostic tools, age and gender distributions between studies as well as the presence of confounding organic or mental disorders (P. Y. Lin & Tseng, 2015). For instance, two studies reported increased GDNF levels in MDD patients compared to controls (Michel et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Interestingly, these were the only studies measuring GDNF in the plasma and the brain of MDD patients. In contrast, rest of the studies assessed either serum or whole blood samples. There seems to be a general trend of reduction in GDNF levels in MDD patients. This argument is based on the fact that data presented in this review is extracted from diverse and heterogeneous groups of MDD patients, from different parts of the world, with differences in age ranges, rates of MDD recurrence, and severity. Moreover, the source and methods for measuring GDNF were very distinct. Thus, variables such as geographical location, age, severity and GDNF assay methods did not affect the MDD associated downhill trend in GDNF levels.

4.2. IGF-1 in Major Depressive Disorder: inconsistent findings

In contrast to GDNF, there were mixed findings with IGF-1 levels in MDD patients when compared with healthy controls. However, majority of studies reported elevated levels of IGF-1 in the MDD patients (Deuschle et al., 1997; Franz et al., 1999; Kopczak et al., 2015; Lesch et al., 1988). Gender-specific relationships between IGF-1 levels and MDD were also described by some studies (Emeny et al., 2014; Rueda Alfaro et al., 2008; van Varsseveld et al., 2015). An exact explanation for these differences among males and females is still unavailable; however, it has been hypothesized that it may be due to sex hormone variations across genders as well as GH- and IGF-1-binding protein level fluctuations (Sievers et al., 2014; van Varsseveld et al., 2015). Van Varsseveld and colleagues described conflicting cross-sectional and longitudinal findings regarding IGF-1 levels and depression (van Varsseveld et al., 2015). While a 3-year follow-up of the cohort found that mild IGF-1 concentrations decreased the probability of minor depression in females, a baseline evaluation of the same group of patients showed that low levels of this molecule may increase the probability of MDD. A baseline assessment of IGF-1 in a West Pomerania cohort also demonstrated that low IGF-1 concentrations increased the odds of depression disorder among females (Sievers et al., 2014). These findings suggest that IGF-1 may have a more acute role in depression, which fades over time (van Varsseveld et al., 2015). The main limitation regarding the compilation of these studies is heterogeneity. All cohorts included in the review have a relatively low prevalence of depressive disorders and depression was screened and diagnosed with the assistance of multiple instruments. Additionally, there were significant differences in the source and techniques for measuring IGF-1, age of population, depression severity and antidepressant use.

4.3. Elevated VEGF levels in Major Depressive Disorder

The majority of the VEGF studies included in this review reported increased serum, plasma and mRNA expression levels in MDD individuals compared to controls. A recent meta-analysis study that focused on clinical studies that assessed changes in VEGF peripheral (plasma, serum, or whole blood) concentrations in MDD patients reported similar conclusions (A. F. Carvalho et al., 2015). Previous non-meta-analytical reviews that aimed to investigate the role of VEGF in depression also described such trend in VEGF level among depressed individuals (Clark-Raymond & Halaris, 2013; Fournier & Duman, 2012). Two studies that explored VEGF alterations in suicide attempters reported decreased concentrations of this molecule among victims (Isung, Mobarrez, et al., 2012) and attempters (Isung, Aeinehband, et al., 2012). However, role of peripheral or central VEGF levels in suicide risk is unclear (Isung, Mobarrez, et al., 2012; Ventriglia et al., 2009). Regarding VEGF polymorphisms, there were quite a few observations. The first one reported contrasting data about the association between VEGF 2578 C/A polymorphism and depression. While Iga co-workers did not find any significant correlation (Iga et al., 2007), Viikki and colleagues reported that this polymorphism was associated with treatment-resistant depression (Viikki et al., 2010). Correlations between depression and other polymorphisms were also described by Elfving and colleagues (Elfving et al., 2014) and Galecki and Galecka (Galecki, Galecka, et al., 2013). Finally, the pool of VEGF studies was extremely diverse and any inference from the combination of data from them might linger with certain limitations.

4.4. Impact of antidepressant treatment on GDNF, IGF-1 and VEGF in MDD patients

Another confounding factor that worth to mention is, use of antidepressants by patients at the time of evaluation in most studies. However, not all studies investigated their effects on neurotrophins. Previous reports suggest a significant association between SSRI and SNRI use with an increase in GDNF level (Zhang et al., 2008). Moreover, amitriptyline and paroxetine use was correlated with a decrease in IGF-1 plasma levels (Weber-Hamann et al., 2009). On the contrary, paroxetine substitution for placebo was shown to increase IGF-1 level (Michelson et al., 2000). In addition, duloxetine use among patients that responded to a 6-week course of this medication was associated with an increase in VEGF plasma level (Fornaro et al., 2013). This finding is of particular interest since the same study demonstrated that VEGF levels were not increased at baseline, contrasting with the majority of the literature in the present review. In addition to the classic regulation of monoaminergic activity, modulation of VEGF metabolism has been theorized to be instrumental in the mechanism of action of many antidepressant medications (Nowacka & Obuchowicz, 2012; Paslakis et al., 2012; Warner-Schmidt & Duman, 2008). An antidepressant effect of VEGF per se has also been described, which also corroborate with the hypothesis that VEGF might enhance neurogenesis (Nowacka & Obuchowicz, 2012; Warner-Schmidt & Duman, 2008). A better understanding of how antidepressant therapies modify GDNF, IGF-1 and VEGF metabolisms would permit the development of novel molecules targeting these neurotrophins, expanding the relatively limited current therapeutic arsenal against depression and other mood disorders (Hoshaw et al., 2005; Nowacka & Obuchowicz, 2012; Scola & Andreazza, 2015; Walker, 2013; Warner-Schmidt & Duman, 2008).

4.5. Limitations

Our review was restricted to peer-reviewed journals published in English. Herein we aimed to provide a comprehensive review of the field. Therefore, we included genetic studies as well as studies in which GDNF, VEGF and IGF-1 were measured in different body compartments. In addition, most studies so far has assayed these trophic mediators in the periphery. Notwithstanding, the “periphery as a window to the brain” model has provided valuable mechanistic insights in several psychiatric disorders, including MDD. Clearly, the extent to which peripheral findings reflect signaling mechanisms in the CNS remains to be established. To the best of our understanding, there are no studies that simultaneously examined peripheral and CNS levels of these trophic factors. Future studies that may examine peripheral and CNS levels of these trophic factors in treatment naïve MDD patients, MDD patients on antidepressant medications, and healthy controls may help to further substantiate their crucial role in MDD.

5. Conclusion

Based on extant data, we found that MDD patients have low GDNF and simultaneously high VEGF levels, while role of IGF-1 is still ambiguous (Figure 1; Table 1–3). The typical approach to the diagnosis and management of major depression has always been clinical, based on subjective findings and complaints. However, these practices are often associated with a great variability and imprecision, especially when compared to standardized assessments. The development of clinically useful biomarkers for MDD could significantly improve this scenario, allowing the identification of target populations, increasing diagnostic precision and refining therapeutic strategies (Scarr et al., 2015). Currently, there is only one commercial biological test available for clinical use, the MDDScore, which measures 9-biomarkers (alpha1 antitrypsin, apolipoprotein CIII, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, cortisol, epidermal growth factor, myeloperoxidase, prolactin, resistin and soluble tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor type II) associated with neurotrophic, metabolic, inflammatory, and HPA axis pathways (Scarr et al., 2015). It has been questioned whether GDNF, IGF-1 and VEGF could be potentially used for this purpose as well (A. F. Carvalho et al., 2015; Clark-Raymond & Halaris, 2013; P. Y. Lin & Tseng, 2015; Szczesny et al., 2013). Despite significant data supporting that these molecules might have an important role in the pathophysiology of MDD, it is still unclear if they would be clinically useful biomarkers for depression (A. F. Carvalho et al., 2015). Thus, large scale studies examining role of these trophic factors in MDD are warranted. Such studies may help to improve our understanding about their potential as biomarkers for depression.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized mechanism

Highlights.

In general, MDD patients had low GDNF mRNA and protein levels.

There is an ambiguity about the role of IGF-1 in MDD.

Studies also suggest high VEGF levels in MDD patients.

Abbreviations

- MDD

Major Depressive Disorder

- YLD

Years Lost due to Disability

- BDNF

Brain derived neurotrophic factor

- GDNF

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor-1

- BD

Bipolar Disorder

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-β

- GFR α1

GDNF-family receptors α1

- IGF-IR

Tyrosine kinase receptor

- ECS

Electroconvulsive therapy

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- SSRI

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- SNRI

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

- HDRS

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- USA

United States of America

- GDS

Geriatric Depression Scale

- GH

Growth hormone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arnold SE, Xie SX, Leung YY, Wang LS, Kling MA, Han X, Shaw LM. Plasma biomarkers of depressive symptoms in older adults. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e65. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach MA, Shen-Orr Z, Lowe WL, Jr, Roberts CT, Jr, LeRoith D. Insulin-like growth factor I mRNA levels are developmentally regulated in specific regions of the rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1991;10(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(91)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berent D, Macander M, Szemraj J, Orzechowska A, Galecki P. Vascular endothelial growth factor A gene expression level is higher in patients with major depressive disorder and not affected by cigarette smoking, hyperlipidemia or treatment with statins. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2014;74(1):82–90. doi: 10.55782/ane-2014-1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AF, Kohler CA, McIntyre RS, Knochel C, Brunoni AR, Thase ME, Berk M. Peripheral vascular endothelial growth factor as a novel depression biomarker: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho LA, Bergink V, Sumaski L, Wijkhuijs J, Hoogendijk WJ, Birkenhager TK, Drexhage HA. Inflammatory activation is associated with a reduced glucocorticoid receptor alpha/beta expression ratio in monocytes of inpatients with melancholic major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e344. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho LA, Torre JP, Papadopoulos AS, Poon L, Juruena MF, Markopoulou K, Pariante CM. Lack of clinical therapeutic benefit of antidepressants is associated overall activation of the inflammatory system. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(1):136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Dowlatshahi D, MacQueen GM, Wang JF, Young LT. Increased hippocampal BDNF immunoreactivity in subjects treated with antidepressant medication. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(4):260–265. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Raymond A, Halaris A. VEGF and depression: a comprehensive assessment of clinical data. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(8):1080–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Raymond A, Meresh E, Hoppensteadt D, Fareed J, Sinacore J, Halaris A. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor: a potential diagnostic biomarker for major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;59:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschle M, Blum WF, Strasburger CJ, Schweiger U, Weber B, Korner A, Heuser I. Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) plasma concentrations are increased in depressed patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1997;22(7):493–503. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, Miranda AS, Talib LL, Gattaz WF, Forlenza OV. Circulating Glial-derived neurotrophic factor is reduced in late-life depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(1):135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dome P, Halmai Z, Dobos J, Lazary J, Gonda X, Kenessey I, Faludi G. Investigation of circulating endothelial progenitor cells and angiogenic and inflammatory cytokines during recovery from an episode of major depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):1159–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dome P, Teleki Z, Rihmer Z, Peter L, Dobos J, Kenessey I, Dome B. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and depression: a possible novel link between heart and soul. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14(5):523–531. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman CH, Schlesinger L, Terwilliger R, Russell DS, Newton SS, Duman RS. Peripheral insulin-like growth factor-I produces antidepressant-like behavior and contributes to the effect of exercise. Behav Brain Res. 2009;198(2):366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Heninger Gr Fau - Nestler EJ, Nestler EJ. A molecular and cellular theory of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54 doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830190015002. (0003-990X (Print)) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duric V, Duman RS. Depression and treatment response: dynamic interplay of signaling pathways and altered neural processes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(1):39–53. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1020-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y, Rizavi HS, Conley RR, Roberts RC, Tamminga CA, Pandey GN. Altered gene expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and receptor tyrosine kinase B in postmortem brain of suicide subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):804–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfving B, Buttenschon HN, Foldager L, Poulsen PH, Grynderup MB, Hansen AM, Mors O. Depression and BMI influences the serum vascular endothelial growth factor level. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(9):1409–1417. doi: 10.1017/S1461145714000273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emeny RT, Bidlingmaier M, Lacruz ME, Linkohr B, Peters A, Reincke M, Ladwig KH. Mind over hormones: sex differences in associations of well-being with IGF-I, IGFBP-3 and physical activity in the KORA-Age study. Exp Gerontol. 2014;59:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornaro M, Rocchi G, Escelsior A, Contini P, Ghio M, Colicchio S, Martino M. VEGF plasma level variations in duloxetine-treated patients with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(2):590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier NM, Duman RS. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in adult hippocampal neurogenesis: implications for the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. Behav Brain Res. 2012;227(2):440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz B, Buysse DJ, Cherry CR, Gray NS, Grochocinski VJ, Frank E, Kupfer DJ. Insulin-like growth factor 1 and growth hormone binding protein in depression: a preliminary communication. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33(2):121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)00066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galecki P, Galecka E, Maes M, Orzechowska A, Berent D, Talarowska M, Szemraj J. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene (VEGFA) polymorphisms may serve as prognostic factors for recurrent depressive disorder development. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galecki P, Orzechowska A, Berent D, Talarowska M, Bobinska K, Galecka E, Szemraj J. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 gene (KDR) polymorphisms and expression levels in depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1–3):144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilloux JP, Douillard-Guilloux G, Kota R, Wang X, Gardier AM, Martinowich K, Sibille E. Molecular evidence for BDNF- and GABA-related dysfunctions in the amygdala of female subjects with major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(11):1130–1142. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halmai Z, Dome P, Dobos J, Gonda X, Szekely A, Sasvari-Szekely M, Lazary J. Peripheral vascular endothelial growth factor level is associated with antidepressant treatment response: results of a preliminary study. J Affect Disord. 2013;144(3):269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshaw BA, Malberg JE, Lucki I. Central administration of IGF-I and BDNF leads to long-lasting antidepressant-like effects. Brain Res. 2005;1037(1–2):204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iga J, Ueno S, Yamauchi K, Numata S, Tayoshi-Shibuya S, Kinouchi S, Ohmori T. Gene expression and association analysis of vascular endothelial growth factor in major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(3):658–663. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isung J, Aeinehband S, Mobarrez F, Martensson B, Nordstrom P, Asberg M, Jokinen J. Low vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-8 in cerebrospinal fluid of suicide attempters. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e196. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isung J, Mobarrez F, Nordstrom P, Asberg M, Jokinen J. Low plasma vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) associated with completed suicide. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13(6):468–473. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.624549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahl KG, Bens S, Ziegler K, Rudolf S, Kordon A, Dibbelt L, Schweiger U. Angiogenic factors in patients with current major depressive disorder comorbid with borderline personality disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(3):353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karege F, Perret G, Bondolfi G, Schwald M, Bertschy G, Aubry JM. Decreased serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in major depressed patients. Psychiatry Res. 2002;109(2):143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karege F, Vaudan G, Schwald M, Perroud N, La Harpe R. Neurotrophin levels in postmortem brains of suicide victims and the effects of antemortem diagnosis and psychotropic drugs. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;136(1–2):29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopczak A, Stalla GK, Uhr M, Lucae S, Hennings J, Ising M, Kloiber S. IGF-I in major depression and antidepressant treatment response. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(6):864–872. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotan Z, Sarandol E, Kirhan E, Ozkaya G, Kirli S. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor, vascular endothelial growth factor and leptin levels in patients with a diagnosis of severe major depressive disorder with melancholic features. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2012;2(2):65–74. doi: 10.1177/2045125312436572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Kim YK. Increased plasma VEGF levels in major depressive or manic episodes in patients with mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(1–2):181–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Kim YK. Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a peripheral marker for the action mechanism of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;57(4):194–199. doi: 10.1159/000149817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Rupprecht R, Muller U, Pfuller H, Beckmann H. Insulin-like growth factor I in depressed patients and controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;78(6):684–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb06404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F, Suhr J, Diebold S, Heffner KL. Associations between depressive symptoms and memory deficits vary as a function of insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) levels in healthy older adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;42:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PY, Tseng PT. Decreased glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor levels in patients with depression: a meta-analytic study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015:1879–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.004. (Electronic)) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Zhu HY, Li B, Wang YQ, Yu J, Wu GC. Chronic clomipramine treatment restores hippocampal expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in a rat model of depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2–3):367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel TM, Frangou S, Camara S, Thiemeyer D, Jecel J, Tatschner T, Grunblatt E. Altered glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) concentrations in the brain of patients with depressive disorder: a comparative post-mortem study. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(6):413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Amsterdam J, Apter J, Fava M, Londborg P, Tamura R, Pagh L. Hormonal markers of stress response following interruption of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25(2):169–177. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumenko VS, Bazovkina DV, Semenova AA, Tsybko AS, Il’chibaeva TV, Kondaurova EM, Popova NK. Effect of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor on behavior and key members of the brain serotonin system in mouse strains genetically predisposed to behavioral disorders. J Neurosci Res. 2013;91(12):1628–1638. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton SS, Fournier NM, Duman RS. Vascular growth factors in neuropsychiatry. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(10):1739–1752. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1281-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowacka MM, Obuchowicz E. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its role in the central nervous system: a new element in the neurotrophic hypothesis of antidepressant drug action. Neuropeptides. 2012;46(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuki K, Uchida S, Watanuki T, Wakabayashi Y, Fujimoto M, Matsubara T, Watanabe Y. Altered expression of neurotrophic factors in patients with major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(14):1145–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallavi P, Sagar R, Mehta M, Sharma S, Subramanium A, Shamshi F, Mukhopadhyay AK. Serum neurotrophic factors in adolescent depression: gender difference and correlation with clinical severity. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(2):415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paslakis G, Blum WF, Deuschle M. Intranasal insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) as a plausible future treatment of depression. Med Hypotheses. 2012;79(2):222–225. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa AR, Frey BN, Andreazza AC, Cereser KM, Cunha AB, Quevedo J, Kapczinski F. Increased serum glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor immunocontent during manic and depressive episodes in individuals with bipolar disorder. Neurosci Lett. 2006;407(2):146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda Alfaro S, Serra-Prat M, Palomera E, Falcon I, Cadenas I, Boquet X, Puig Domingo M. Hormonal determinants of depression and cognitive function in independently-living elders. Endocrinol Nutr. 2008;55(9):396–401. doi: 10.1016/S1575-0922(08)75076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarr E, Millan MJ, Bahn S, Bertolino A, Turck CW, Kapur S, Dean B. Biomarkers for Psychiatry: The Journey from Fantasy to Fact, a Report of the 2013 CINP Think Tank. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyv042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scola G, Andreazza AC. The role of neurotrophins in bipolar disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2015;56:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata T, Yamagata H, Uchida S, Otsuki K, Hobara T, Higuchi F, Watanabe Y. The alteration of hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and its target genes in mood disorder patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;43:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers C, Auer MK, Klotsche J, Athanasoulia AP, Schneider HJ, Nauck M, Grabe HJ. IGF-I levels and depressive disorders: results from the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(6):890–896. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczesny E, Slusarczyk J, Glombik K, Budziszewska B, Kubera M, Lason W, Basta-Kaim A. Possible contribution of IGF-1 to depressive disorder. Pharmacol Rep. 2013;65(6):1622–1631. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(13)71523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi M, Hashimoto R, Hisaoka K, Tsuchioka M, Kunugi H. Plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor 2 in patients with major depressive disorders. J Neural Transm. 2010;117(9):1119–1122. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi M, Hisaoka K, Nishida A, Tsuchioka M, Miyoshi I, Kozuru T, Yamawaki S. Decreased levels of whole blood glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) in remitted patients with mood disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9(5):607–612. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705006085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taliaz D, Stall N, Dar DE, Zangen A. Knockdown of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in specific brain sites precipitates behaviors associated with depression and reduces neurogenesis. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(1):80–92. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ, Hong CJ, Liou YJ, Chen TJ, Chen ML, Hou SJ, Yu YW. Haplotype analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFA) gene and antidepressant treatment response in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009;169(2):113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng PT, Lee Y, Lin PY. Age-associated decrease in serum glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor levels in patients with major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;40:334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Varsseveld NC, van Bunderen CC, Sohl E, Comijs HC, Penninx BW, Lips P, Drent ML. Serum insulin-like growth factor 1 and late-life depression: a population-based study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;54:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventriglia M, Zanardini R, Pedrini L, Placentino A, Nielsen MG, Gennarelli M, Bocchio-Chiavetto L. VEGF serum levels in depressed patients during SSRI antidepressant treatment. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(1):146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viikki M, Anttila S, Kampman O, Illi A, Huuhka M, Setala-Soikkeli E, Leinonen E. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) polymorphism is associated with treatment resistant depression. Neurosci Lett. 2010;477(3):105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker FR. A critical review of the mechanism of action for the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: do these drugs possess anti-inflammatory properties and how relevant is this in the treatment of depression? Neuropharmacology. 2013;67:304–317. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Hou Z, Yuan Y, Hou G, Liu Y, Li H, Zhang Z. Association study between plasma GDNF and cognitive function in late-onset depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;132(3):418–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner-Schmidt JL, Duman RS. VEGF as a potential target for therapeutic intervention in depression. CurrOpin Pharmacol. 2008;8(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber-Hamann B, Blum WF, Kratzsch J, Gilles M, Heuser I, Deuschle M. Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) serum concentrations in depressed patients: relationship to saliva cortisol and changes during antidepressant treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2009;42(1):23–28. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Ru B, Sha W, Xin W, Zhou H, Zhang Y. Performance on the Wisconsin card-sorting test and serum levels of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with major depressive disorder. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2014;6(3):302–307. doi: 10.1111/appy.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang Z, Sha W, Xie C, Xi G, Zhou H, Zhang Y. Effect of treatment on serum glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in bipolar patients. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(1–2):326–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang Z, Xie C, Xi G, Zhou H, Zhang Y, Sha W. Effect of treatment on serum glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in depressed patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(3):886–890. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]