Abstract

Objective

To investigate treatment outcome and mediators of Cognitive-Behavioral Group Therapy (CBGT) vs. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) vs. Waitlist (WL) in patients with generalized social anxiety disorder (SAD).

Method

108 unmedicated patients (55.6% female; mean age = 32.7, SD = 8.0; 43.5% Caucasian, 39% Asian, 9.3% Hispanic, 8.3% other) were randomized to CBGT vs. MBSR vs. WL and completed assessments at baseline, post-treatment/WL, and at 1-year follow-up, including the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale – Self-Report (primary outcome) as well as measures of treatment-related processes.

Results

Linear mixed model analysis showed that CBGT and MBSR both produced greater improvements on most measures compared to WL. Both treatments yielded similar improvements in social anxiety symptoms, cognitive reappraisal frequency and self-efficacy, cognitive distortions, mindfulness skills, attention focusing and rumination. There were greater decreases in subtle avoidance behaviors following CBGT than MBSR. Mediation analyses revealed that increases in reappraisal frequency, mindfulness skills, attention focusing and attention shifting, and decreases in subtle avoidance behaviors and cognitive distortions mediated the impact of both CBGT and MBSR on social anxiety symptoms. However, increases in reappraisal self-efficacy and decreases in avoidance behaviors mediated the impact of CBGT (vs. MBSR) on social anxiety symptoms.

Conclusions

CBGT and MBSR both appear to be efficacious for SAD. However, their effects may be a result of both shared and unique changes in underlying psychological processes.

Keywords: social anxiety, cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness, meditation, mediators

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is highly prevalent (lifetime prevalence rate of 12.1%; (Kessler et al., 2005) and has an early onset that often precedes the onset of other anxiety disorders, substance use, and major depression (Otto et al., 2001). SAD is associated with significant impairment in social, educational, and occupational functioning (Acarturk, Graaf, Straten, ten Have, & Cuijpers, 2008), and entails a substantial personal and societal burden (Acarturk et al., 2009; Patel, Knapp, Henderson, & Baldwin, 2002).

Although SAD is highly persistent when untreated (Blanco et al., 2011), several psychological interventions have been shown to reliably reduce social anxiety symptoms. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 32 randomized controlled trials (RCT) of cognitive and/or behavioral interventions for SAD (N = 1,479) showed superior effects on social anxiety symptoms relative to waitlist (Cohen's d = 0.86), psychological placebo (d = 0.34), and pill-placebo (d = 0.36) (Powers, Sigmarsson, & Emmelkamp, 2008), with treatment gains maintained at follow-up (d = 0.76). Interestingly, there were no significant differences among combined exposure and cognitive therapy (vs. control: d = 0.68), exposure (vs. control: d = 0.89), and cognitive treatments (vs. control: d = 0.80). Also, no significant differences were observed for group (d = 0.68) versus individual (d = 0.69) treatments. Effect sizes were not associated with sample size, publication year, or number of hours of treatment further supporting the reliable and robust effects of cognitive and behavioral therapies for SAD.

Other more recent studies have shown the efficacy of nontraditional therapies, such as Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). For example, a recent meta-analysis (Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010) showed that mindfulness-based interventions reliably reduced anxiety symptoms across a variety of psychiatric and medical populations (Hedges's g = 0.63), and even more so in the subgroup of patients with anxiety and mood disorders (g = 0.97). In adults with SAD, MBSR has demonstrated improvement in mood, functioning, social anxiety, and quality of life (Koszycki, Benger, Shlik, & Bradwejn, 2007), self-esteem, negative self-views, trait anxiety, negative emotional reactivity, and depression (Goldin, Ziv, Jazaieri, & Gross, 2012; Goldin, Ziv, Jazaieri, Hahn, & Gross, 2013; Goldin & Gross, 2010). A recent review (Norton, Abbott, Norberg, & Hunt, 2015) concluded that mindfulness and acceptance-based treatments significantly reduce social anxiety symptoms, but that methodological weaknesses strongly limit inferences and comparisons to gold-standard psychosocial interventions for SAD such as CBT.

It is important to further examine the comparative efficacy of CBT and MBSR, and to determine whether they produce their effects through similar or different psychological mechanisms of action. To date, few studies have directly addressed whether CBT and MBSR (or similar treatments) have comparable efficacy for treatment of SAD. One study compared cognitive-behavioral group therapy (CBGT; n = 27) to MBSR (n = 26) in patients with SAD. CBGT and MBSR were comparable in improving mood, functioning, and quality of life, but CBGT produced significantly greater improvement in social anxiety symptoms, as well as greater response and remission rates (Koszycki et al., 2007). However, inferences from this study are somewhat constrained due to methodological issues, including no control group, inclusion of measurement of treatment adherence, or measurement of follow-up outcomes, and inclusion of patients with concurrent use of psychotropic medications, and unequal duration of treatment. A recent RCT compared CBGT (n = 53) to mindfulness and acceptance-based group therapy (MAGT; n = 53) and to a waitlist control group (n = 31) (Kocovski, Fleming, Hawley, Huta, & Antony, 2013). MAGT combined abbreviated mindfulness exercises from mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 1995), experiential and didactic components of acceptance and commitment therapy (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999), and in-session and in-vivo exposure exercises. Both interventions were more efficacious than waitlist, but not different from each other in reducing social anxiety symptoms or scores on most of the secondary outcome variables. A different RCT compared individual CBT (n = 40) to individual ACT (n = 34) and to a waitlist control group (n = 26) and found a similar pattern of greater efficacy for both treatments than waitlist and no differential treatment effect on multiple indices of social anxiety (Craske et al., 2015). However, potential confounds include permitting participants with concurrent use of psychotropic medications and alternative (i.e., non-cognitive or behavioral) psychotherapies.

Far less is known about the mechanisms of action of CBT and MBSR. Investigations of potential mechanisms of change during CBT for SAD have identified probability bias for negative social events (Smits, Rosenfield, McDonald, & Telch, 2006), estimated probability and estimated cost of negative social events, safety behaviors (Hoffart, Borge, Sexton, & Clark, 2009), and anticipated aversive social outcomes (Hofmann, 2004). Formal mediation analyses indicate that decreases in maladaptive interpersonal beliefs (Boden et al., 2012) and negative cognitions (Niles et al., 2014), as well as increases in cognitive reappraisal (Kocovski, Fleming, Hawley, Ho, & Antony, 2015), reappraisal success (Goldin et al., 2014), reappraisal self-efficacy (Goldin et al., 2012), and positive self-views (Goldin et al., 2013) mediate the effect of CBT on social anxiety symptoms. Other research has implicated rumination, specifically the brooding subtype, as an important predictor of changes in social anxiety during CBT for SAD (Brozovich et al., 2015). Comparable studies of the mechanisms of action of mindfulness-based treatments are less plentiful. However, a recent meta-analysis of meditation studies examined the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of MBSR and MBCT on psychological functioning and well-being (Gu, Strauss, Bond, & Cavanagh, 2015). This analysis found strong evidence for cognitive and emotional reactivity (stress reactivation of negative thinking and emotional patterns), moderate evidence for mindfulness, rumination, and worry, and preliminary but insufficient evidence for self-compassion and psychological flexibility as mediators of outcome. However, the authors state that most of the reviewed studies had key methodological shortcomings and highlight the need for more rigorous investigation of mediators of MBSR and MBCT, particularly given the recent emphasis on attention control, emotion regulation, self-awareness, and self-regulation as key variables (Tang, Hölzel, & Posner, 2015).

The Present Study

Our goals in this RCT of CBGT vs. MBSR (vs. WL) were to examine (1) differential efficacy and durability of effect of CBGT vs. MBSR on social anxiety symptoms (primary outcome) as well as measures of treatment-related processes, and (2) potential mediators of changes in social anxiety symptoms in patients with generalized SAD. Hypothesis 1 (outcomes): We expected greater statistical and clinically significant improvement on the primary outcome (social anxiety symptoms) for (a) both CBGT and MBSR (vs. WL), and (b) for CBGT (vs. MBSR) immediately and 1-year post-treatment. Hypothesis 2 (mediators): We expected that changes in cognitive reappraisal frequency and self-efficacy, subtle avoidance, and cognitive distortions would mediate the impact of CBGT vs. WL, and that changes in mindfulness skills, attention focusing, attention shifting, and rumination would mediate the impact of MBSR vs. WL on social anxiety symptoms immediately post-treatment. We further explored whether any of these variables differed in their mediational effect for CBGT vs. MBSR.

Method

Participants

Patients met DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for a principal diagnosis of generalized SAD based on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for the DSM-IV-Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L; (Di Nardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994). Patients met criteria for the “generalized” subtype of SAD if they endorsed greater then moderate social fear in 5 or more distinct social situations assessed by the ADIS-IV-L. Furthermore, participants had to achieve a score greater than 60 on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale – Self-Report (LSAS-SR), the cut-off score for the generalized subtype of SAD as determined by receiver operator characteristics analysis of the LSAS-SR (Rytwinski et al., 2009). Participants were excluded for pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy during the past year, participation in CBT for any anxiety disorder during the last two years, any previous MBSR course, previous participation in long-term meditation retreats, history of regular mediation practice of 10 minutes or more 3 or more times per week, history of neurological disorders, cardiovascular disorders, thought disorders, or bipolar disorder, as well as current substance and alcohol abuse/dependence.

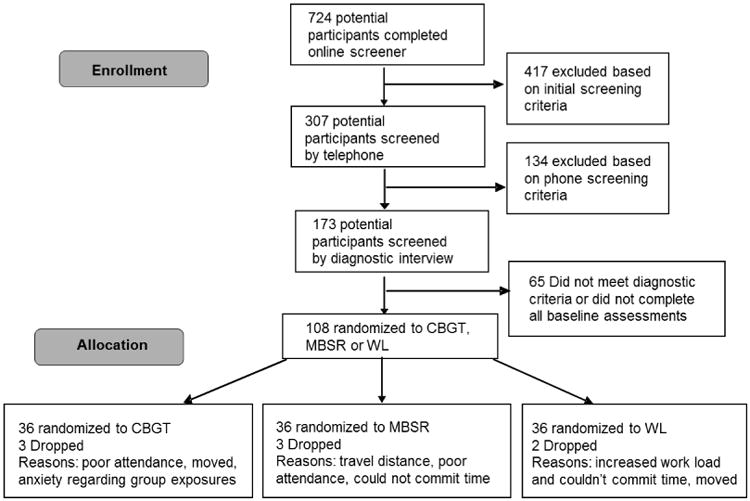

From 2012 to 2014, 724 potential participants completed an online screener, of whom 307 were screened by telephone (see Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, Figure 1). The 173 who were potentially eligible were administered the ADIS-IV-L in person to determine whether they met diagnostic inclusion/exclusion criteria. After 65 patients were excluded because they did not meet diagnostic criteria or failed to complete baseline assessments, the remaining 108 patients were randomly assigned to CBGT (n = 36), MBSR (n = 36), or WL (n = 36). Dropout from treatment was low and did not differ (χ2(2, N = 108) = 1.05, p = .59) across CBGT (n = 2; 6%), MBSR (n = 3; 8%) and WL (n = 1; 3%).

Figure 1.

Consolidated standards of reporting trials diagram for a randomized controlled trial of CBGT vs. MBSR vs. WL groups.

Procedure

Potential patients were recruited through clinician referrals and community listings. After passing a telephone screening, a face-to-face diagnostic interview was used to determine current and past Axis I psychiatric disorders and current clinician-rated severity. After completing all baseline assessments, each set of six consecutive patients entered one group (CBGT, MBSR or WL), which were sequenced randomly so that at the end of the study we had six groups of six patients each who were randomized to CBGT, MBSR or WL. Patients completed assessments again at post-treatment and every 3 months during the 1-year follow-up. Patients received treatment at no cost and $150 for completing the 1-year follow-up behavioral session. All participants provided informed consent in accordance with the Institutional Review Board.

Diagnostic Assessment

Diagnostic interviews were conducted at baseline using the ADIS-IV-L (Di Nardo et al., 1994). The ADIS has demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability (Brown, Di Nardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001) and provides clinician-rated severity for each assigned diagnosis on a 0-8 scale. To assess the inter-rater reliability of the ADIS-IV-L, we had Ph.D. clinical psychologists and doctoral students review 20% of the interviews. There was 100% agreement with the original principal diagnosis of SAD (κ = 1.0).

Measures

Primary outcome measure

Severity of social anxiety symptoms was assessed with the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-Self-Report (LSAS-SR; Fresco et al., 2001; Liebowitz, 1987) which assesses patients' reactions to 11 social interaction situations and 13 performance situations. A 4-point Likert-type scale is used for ratings of fear and of avoidance, with a range from 0 (none and never, respectively) to 3 (severe and usually, respectively) for each situation during the past week. Ratings are summed for a total LSAS-SR score (range = 0-144). The LSAS-SR has good reliability and construct validity (Rytwinski et al., 2009), and its internal consistency was excellent in this study (Cronbach's α = .92).

Treatment-related processes

For CBGT, we assessed four candidate mechanisms. We measured cognitive reappraisal frequency and cognitive reappraisal self-efficacy with an extended version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Goldin, Manber-Ball, Werner, Heimberg, & Gross, 2009; Gross & John, 2003). The instrument utilizes a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) and includes eight items assessing cognitive reappraisal frequency (CR-F), and eight items assessing cognitive reappraisal self-efficacy (CR-SE). Internal consistency for CR-F (α = .89) and CR-SE (α = .93) were good at baseline. We measured subtle avoidance using the Subtle Avoidance Frequency Examination (SAFE; Cuming et al., 2009), a 32-item measure of safety behaviors. It has good discriminant and construct validity in patients with SAD, and internal consistency was good in this study at baseline (α = .91). We measured cognitive distortions using the Cognitive Distortions Questionnaire (De Oliveira, 2015) which is comprised of 15 items that assess the frequency and intensity of a variety of common cognitive errors. The CD-Quest has shown good internal consistency (αs = .83 - .86) and convergent validity with self-report measures of depression, anxiety, and automatic thoughts (rs = .51 - .65; De Oliveira, 2015; Morrison et al., 2015). Internal consistency was excellent in this study at baseline (α = .91).

For MBSR, we assessed four candidate mechanisms. We measured mindfulness skills using the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006), a 39-item self-report measure of five mindfulness factors: observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-reactivity to inner experience, and non-judging of inner experience. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The instrument has good internal consistency in general (Baer et al., 2006) and it was excellent in this study at baseline (α = .91). We used the Attentional Control Scale (ACS; Derryberry & Reed, 2002) to measure attention focusing (9-items) and shifting (10 items). Internal consistency is good for the focusing subscale (α = .82) and acceptable for the shifting subscale (α = .68; Olafsson et al., 2011). In this study, internal consistency was good for both subscales (focusing α = .85; shifting α = .74).

We used the brooding subscale of the Ruminative Responses Scale (Treynor et al., 2003) to examine this maladaptive form of rumination. Brooding is depicted as moody rumination or “a passive comparison of one's current situation with some unachieved standard” (Treynor et al., 2003, p. 256). Five items are rated on Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). The brooding subscale has been shown to have good reliability in other studies (α = .77; Treynor et al., 2003), as well as in the current study (α = .76).

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive behavioral group therapy (CBGT) was delivered by two Ph.D. clinical psychologists trained by Dr. Richard Heimberg to implement his CBGT for SAD protocol (Heimberg & Becker, 2002). Groups of six individuals met for 12 sessions of 2.5 hours each (total time = 30 hours). The participants also used selected portions of the client workbook developed by (Hope, Heimberg, & Turk, 2010) to supplement relevant portions of the protocol. The treatment comprised four major components: (1) psychoeducation and orientation to CBGT; (2) cognitive restructuring skills; (3) graduated exposure to feared social situations, within session and as homework; and (4) relapse prevention and termination. Further details are available elsewhere (Heimberg & Becker, 2002).

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

MBSR followed the standard curriculum outline compiled in 1993 by Jon Kabat-Zinn except that the one-day meditation retreat was converted to four additional weekly group sessions between the standard class 6 and 7 so that there were 12 weekly 2.5 hour sessions. This was done to match the CBGT protocol in duration and time. The MBSR intervention was delivered by a University of Massachusetts Center for Mindfulness certified MBSR instructor with more than 30 years of teaching experience. To support the practice, each participant was given A Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Workbook (Stahl & Goldstein, 2010), which includes descriptions of mindfulness exercises together with pre-recorded audio files to support ongoing practice.

Adherence and Treatment Completer Status

To assure treatment adherence, a trained rater was present in every CBGT and MBSR session to conduct real-time rating of adherence using adherence scales developed for CBGT and for MBSR. Adherence ratings indicated that the CBGT therapists and MBSR instructor were “in protocol” (rating > 4 of 5 for each session) with no between-group differences, t(11) = 0.83, p = .43, in adherence for CBGT, Mean ± SD: 4.92 ± 0.27, versus MBSR, 4.81 ± 0.17. Based on a criterion of 9 of 12 sessions attended for treatment completer status, 33 (92%) patients completed CBGT and 33 (92%) completed MBSR. Mean number of sessions attended for CBGT (Mean ± SD = 10.47 ± 1.56) and MBSR (10.37 ± 2.09) were not significantly different, t(71) = 0.22, p = .82. The mean number of in-session exposures per patient in CBGT was 4.5 (SD = 0.84).

Statistical Analyses

Outcomes

All results were analyzed using an intention-to-treat approach based on treatment assignments. Longitudinal analysis was used to assess change over time and relate the changes to treatment group assignment. We implemented linear mixed-effects models (LMM) for continuous outcomes in SPSS (version 22) with the MIXED procedure to examine change pre vs. post-CBGT vs. MBSR, CBGT vs. WL and MBSR vs. WL, with maximum likelihood as the method of estimation. The parameters of main interest were the fixed effect interaction terms between groups and times, describing whether the patients had differential change from pre-to-post treatment groups. The model included random intercepts and identity covariance structure. We report effect sizes as Cohen's d (Cohen, 1988) computed as the mean difference divided by the pooled standard deviation of the difference score. Cohen's d for paired sample statistical tests (e.g., within groups t-tests comparing baseline to post-treatment) was computed as the mean difference divided by the standard deviation of the difference score.

To determine clinically significant improvement, we computed reliable and clinically significant change for the primary outcome measure (LSAS-SR). Reliable change (RC) was computed as 1.96*standard error of change, which resulted in a criterion of reduction in LSAS-SR greater than 13.83. Clinically significant change (CSC) consists of RC plus a shift from dysfunctional to the functional range. Using Jacobson's method C (Jacobson, Roberts, Berns, & McGlinchey, 1999; Jacobson & Truax, 1991), the CSC criterion was determined by an LSAS-SR score lower than the halfway point (47.68) between 2 SD above the mean of non-anxious healthy adults (Mean ± SD, 14.35 ± 12.7; Fresco et al., 2001) and 2 SD below the baseline mean of SAD patients (90.89 ± 17.64) measured in this study.

Mediation

We implemented mediation models to investigate Mediators (M) of the effects of treatment Group (G) on treatment Outcome (O), namely, residualized social anxiety symptoms (LSAS-SR) immediately following treatment/WL. We investigated four putative CBT-related mediators (reappraisal frequency, reappraisal self-efficacy, subtle avoidance, cognitive distortions) as well as four putative MBSR-related mediators (mindfulness skills, attention focusing, attention shifting, and rumination), computed as residualized scores. We used Hayes' (2012) SPSS MEDIATE macro which uses ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to estimate direct (impact of G on O) and indirect (impact of G on O through M) effects, and allows analysis of 3 groups simultaneously when coded as categorical variables. Statistical significance was determined at p < .05 if the 95% bias-corrected percentile bootstrapped confidence interval (with 5,000 resamples) of the indirect effect point estimate did not contain zero (see Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008). Effect size for the mediation effect (PM) is the ratio of the indirect effect (a*b) to the total effect c = a*b + c′ (Preacher & Kelley, 2011; Wen & Fan, 2015).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

The three groups did not differ significantly (all ps > .05) in gender, age, education, ethnicity, marital status, income, current or past Axis I comorbidity, past psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy, age at SAD symptom onset, and years since symptom onset (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristic of Randomized Participants.

| Characteristic | CBGT (n = 36) | MBSR (n = 36) | WL (n = 36) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males, No. (%) | 16 (44.4) | 16 (44.4) | 16 (44.4) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 34.1 (8.0) | 29.9 (7.6) | 34.1 (7.8) |

| Education, mean (SD), years | 17.4 (3.3) | 16.2 (1.7) | 16.5 (2.9) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 18 (50.0) | 14 (38.9) | 15 (41.7) |

| Asian | 15 (41.7) | 13 (36.1) | 14 (38.9) |

| Latino | 2 (5.5) | 7 (19.4) | 1 (2.8) |

| African American | 0 | 1 (2.8) | 0 |

| American Indian / Alaskan Native | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.8) |

| More than One Race | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 5 (13.9) |

| Yearly income, No. (%) | |||

| <10k | 3 (8.3) | 3 (8.3) | 1 (2.8) |

| 10-25k | 3 (8.3) | 2 (5.6) | 4 (11.1) |

| 25-50k | 5 (13.9) | 5 (13.9) | 5 (13.9) |

| 50-75k | 6 (16.7) | 5 (13.9) | 3 (8.3) |

| 75-100k | 4 (11.1) | 3 (8.3) | 4 (11.1) |

| >100k | 9 (25.0) | 9 (25.0) | 10 (27.8) |

| Marital status, No. (%) | |||

| Single, never married | 20 (55.6) | 23 (63.9) | 18 (50.0) |

| Married | 12 (33.3) | 8 (23.8) | 16 (44.4) |

| Divorced, separated, widowed | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Living with partner | 3 (8.3) | 5 (13.9) | 1 (2.8) |

| Current Axis I Comorbidity, No. (%) | |||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 13 (36.1) | 10 (27.8) | 8 (22.2) |

| Specific phobia | 4 (11.1) | 10 (27.8) | 5 (13.9) |

| Panic disorder | 8 (22.2) | 4 (11.1) | 2 (5.6) |

| Major depressive disorder | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.6) | 1 (2.8) |

| Dysthymic disorder | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) | 3 (8.3) |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 0 | 1 (2.8) | 0 |

| Past Axis I Comorbidity, No. (%) | |||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 1 (2.8) |

| Panic disorder | 3 (8.3) | 3 (8.3) | 1 (2.8) |

| Major depressive disorder | 13 (36.1) | 17 (47.2) | 12 (33.3) |

| Dysthymic disorder | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.6) |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Substance abuse disorder | 3 (8.3) | 3 (8.3) | 2 (5.6) |

| Eating disorder | 2 (5.6) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.6) |

| Past non-CBT Psychotherapy, No. (%) | 20 (55.6) | 18 (50.0) | 23 (63.9) |

| Past Pharmacotherapy, No. (%) | 15 (41.7) | 15 (41.7) | 13 (36.1) |

| Age at symptom onset, mean (SD), years | 9.0 ± 5.1 | 9.4 ± 5.1 | 8.3 ± 5.0 |

| Years since symptom onset, mean (SD), years | 25.1 ± 1.3 | 20.5 ± 9.1 | 25.8 ± 8.3 |

Note: All comparisons (between-group t-test or χ2 tests) are non-significant, p >.05. CBGT= cognitive behavioral group therapy, CBT = cognitive-behavioral therapy, MBSR=mindfulness-based stress reduction, WL=waitlist group, HC=healthy controls, M=mean, SD=standard deviation, No=number, % = percentage, k = thousand dollars.

Treatment Effects on Social Anxiety Symptoms

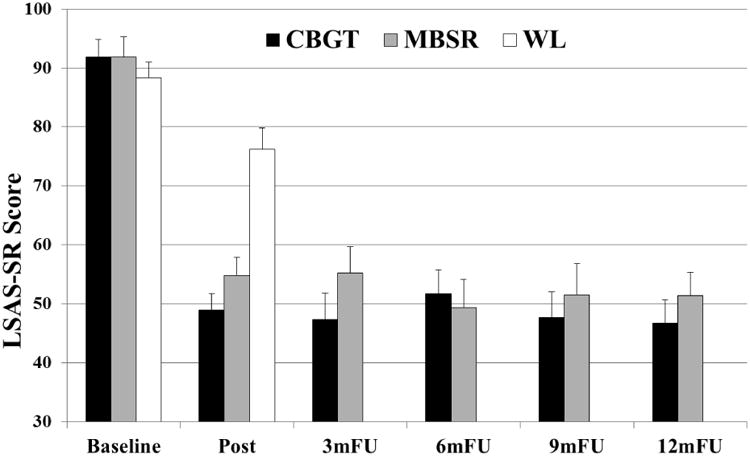

Linear mixed model (LMM) revealed significantly greater reduction (all ts > 5.36, ps < .001) of social anxiety symptoms (LSAS-SR) for CBGT (raw score change from baseline = -44; percent change from baseline level = 48%; Cohen's d = 1.56) and MBSR (-36.5; 40%; d = 1.43) compared to WL (-12.5; 14%). However, there were no significant differences for CBGT vs. MBSR (t = 1.36, df = 68, p = .18), indicating similar treatment efficacy. Furthermore, to examine the durability of clinical improvement, we tested whether there was equivalent maintenance of reduced social anxiety symptoms from immediately to 1-year post-treatment. LMM showed no significant differences (t = 1.63, df = 52, p = .11), suggesting similar sustained clinical improvement during the 1-year post-CBGT and MBSR period (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Social anxiety symptoms (LSAS-SR) pre/post-CBGT, MBSR and WL, and monthly during 1-year follow-up. Error bars = standard error of the mean. m = months, FU = follow-up assessment time point.

Clinically significant improvement was defined as having occurred for patients who met criteria for both reliable change (LSAS reduction > 14 points) and clinically significant change (LSAS-SR score < 48 at post-treatment). Immediately post-treatment/WL, compared to WL (11.1%), CBGT (44.4%; χ2(1, N = 72) = 9.97, p = .002, Φ = .37) and MBSR (38.9%; χ2(1, N = 72) = 7.41, p = .006, Φ = .32) yielded higher rates of clinically significant improvement, but did not differ significantly from each other, χ2(1, N = 72) = 0.23, p = .63, Φ = .06.

CBGT and MBSR Related Psychological Processes

CBGT-related processes

For cognitive reappraisal frequency, LMM demonstrated significantly greater increases (all ts > 2.60, ps < .05) for CBGT (+1.1; 30%, d = 0.59) and for MBSR (+1.2; 33%, d = 0.71) compared to WL (+0.4; 10%), with no significant CBGT vs. MBSR differences (t = 0.04, df = 59, p = .97). For cognitive reappraisal self-efficacy, LMM demonstrated significantly greater increases (all ts > 2.24, ps < .05) for CBGT (+1.4; 40%; d = 1.05) and for MBSR (+0.8; 22%; d = 0.58) compared to WL (+0.2; 5%), with no significant CBGT vs. MBSR differences (t = 1.77, df = 56, p = .08). For subtle avoidance behaviors, LMM demonstrated significantly greater decreases (all ts > 2.59, ps < .05) for CBGT (-20.1; 24%; d = 1.27) and for MBSR (-9.8; 12%; d = 0.64) compared to WL (-1; 1%), and significantly greater decreases for CBGT vs. MBSR (t = 2.30, df = 66, p = .025). For cognitive distortions, LMM demonstrated significantly greater decreases (all ts > 2.40, ps < .05) for CBGT (-9.1; 32%; d = 0.59) and for MBSR (-8.3; 27.5%; d = 0.67) compared to WL (-1; 3%), with no significant CBGT vs. MBSR differences (t = 0.20, df = 59, p = .84).

MBSR-related processes

For mindfulness skills, LMM demonstrated significantly greater increases (all ts > 5.79, ps < .001) for CBGT (+14.4; 13%; d = 1.67) and for MBSR (+17.6; 17%; d = 1.44) compared to WL (-5.6, 5%), with no significant CBGT vs. MBSR differences (t = 0.78, df = 61, p = .44). For attention focusing, LMM demonstrated greater increases (all ts > 2.21, ps < .05) for CBGT (+1.0; 4.5%; d = 0.50) and for MBSR (+1.1; 5%; d = 0.62) compared to WL (-0.8; 3.5%), with no significant CBGT vs. MBSR differences (t = 0.02, df = 63, p = .99). For attention shifting, LMM showed greater increases (t > 2.56, p = .01) for CBGT (+1.5; 6.5%; d = 0.64) and no significant difference (t = 1.90, p = .06) for MBSR (+0.5; 2%; d = 0.46) compared to WL (-0.9; 4%), with no significant CBGT vs. MBSR differences (t = 0.90, df = 64, p = .37). For rumination, LMM revealed significantly greater decreases (all ts > 2.01, ps < .05) for CBGT (-2.9; 22%; d = 0.94) and for MBSR (-1.5; 11%; d = 0.46) compared to WL (+0.3; 2%), with no significant CBGT vs. MBSR differences (t = 1.27, df = 67, p = .21).

Mediators of CBGT and MBSR Effects

As shown in Table 3, increases in reappraisal frequency, mindfulness skills, attention focusing and attention shifting, as well as decreases in safety behaviors and cognitive distortions each mediated the effect of CBGT vs. WL and MBSR vs. WL on social anxiety symptoms. Increases in reappraisal self-efficacy and decreases in rumination mediated the effect of CBGT vs. WL, but not MBSR vs. WL. For the contrast of the two interventions, there was evidence that increases in reappraisal self-efficacy and decreases in safety behaviors mediated the effect of CBGT (vs. MBSR) on social anxiety symptom reduction.

Table 3. Mediators of the impact of CBGT and MBSR on social anxiety symptoms.

| Mediator | Group contrast | IE, SE, [95% CI] | DE | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reappraisal Frequency | CBGT (vs WL) | -3.46, 2.17, [-9.62, -0.47] | -25.86 | .12 |

| MBSR (vs WL) | -3.78, 2.20, [-9.98, -0.73] | -17.35 | .18 | |

| CBGT (vs. MBSR) | -0.33, 1.52, [-3.50, 2.71] | 8.51 | .04 | |

| Reappraisal Self-Efficacy | CBGT (vs WL) | -5.70, 2.67, [-12.42, -1.68] | -23.62 | .19 |

| MBSR (vs WL) | -2.23, 1.89, [-7.44, 0.32] | -18.90 | .11 | |

| CBGT (vs. MBSR) | 3.46, 1.96, [0.66, 8.73] | 4.72 | .42 | |

| Safety Behaviors | CBGT (vs WL) | -16.53, 4.09, [-25.79, -9.52] | -12.76 | .56 |

| MBSR (vs WL) | -8.28, 2.78, [-14.56, -3.54] | -12.85 | .42 | |

| CBGT (vs. MBSR) | 8.25, 3.86, [2.13, 17.80] | -0.09 | 1.01 | |

| Cognitive Distortions | CBGT (vs WL) | -9.26, 3.63, [-18.50, -3.68] | -20.03 | .32 |

| MBSR (vs WL) | -7.76, 2.75, [-14.20, -3.20] | -13.37 | .37 | |

| CBGT (vs. MBSR) | 1.50, 2.74, [-3.12, 7.92] | 6.66 | .17 | |

| Mindfulness Skills | CBGT (vs WL) | -9.70, 3.37, [-17.69, -4.10] | -19.62 | .33 |

| MBSR (vs WL) | -10.31, 4.09, [-20.36, -3.91] | -11.52 | .47 | |

| CBGT (vs. MBSR) | -0.61, 2.40, -5.91, 3.83] | 8.10 | .08 | |

| Attention Focus | CBGT (vs WL) | -2.83, 2.12, [-9.12, -0.11] | -26.48 | .10 |

| MBSR (vs WL) | -3.12, 2.00, [-8.48, -0.32] | -18.71 | .14 | |

| CBGT (vs. MBSR) | -0.29, 1.72, [-4.08, 3.04] | 7.77 | .04 | |

| Attention Shifting | CBGT (vs WL) | -5.09, 2.90, [-13.31, -1.17] | -24.22 | .17 |

| MBSR (vs WL) | -3.50, 1.90, [-8.50, -0.71] | -18.33 | .16 | |

| CBGT (vs. MBSR) | 1.59, 2.38, [-1.77, 8.26] | 5.89 | .21 | |

| Rumination | CBGT (vs WL) | -5.40, 3.19, [-12.77, -0.69] | -23.89 | .18 |

| MBSR (vs WL) | -2.93, 2.29, [-9.10, 0.02] | -18.19 | .14 | |

| CBGT (vs. MBSR) | 2.46, 2.18, [-0.29, 8.73] | 5.70 | .30 |

Note. IE = indirect effect (a*b) of group on social anxiety symptoms through mediator, SE = standard error, CI = bias corrected bootstrap confidence intervals, DE = direct effect (c′) of group on social anxiety symptoms, ES = effect size ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect (PM = ab / (ab + c′))

Discussion

The goals of this study were to investigate the comparative effects of CBGT vs. MBSR (vs. WL) on treatment outcome, and test for mediators of responses to CBGT and MBSR in adults with SAD. CBGT and MBSR resulted in significant reduction in social anxiety symptoms (LSAS-SR) compared to WL. Thus, the prediction that CBGT would result in greater reduction in social anxiety symptoms compared to MBSR was not supported, either immediately or 1-year post-treatment. Furthermore, analysis of reliable and clinically significant change on the LSAS-SR showed similar rates of clinically significant improvement for CBGT and MBSR. These results converge with the results of a study reporting equivalent impact of CBGT vs. MAGT on social anxiety and secondary outcomes (Kocovski et al., 2013), but diverge from a prior finding of greater reduction in social anxiety symptoms for CBGT vs. MBSR (Koszycki et al., 2007). The use of more refined methods in our RCT, including matching CBGT and MBSR dose, excluding concurrent psychotropic medication use, and confirming protocol adherence, may have contributed to the equivalent efficacy of the two treatments. This pattern of results suggests that MBSR may be as efficacious as CBGT at reducing social anxiety symptoms and maintaining treatment gains.

Measures of treatment-related psychological processes provided additional evidence for similar effects of CBGT and MBSR, specifically, decreasing cognitive distortions and rumination, and increasing reappraisal frequency and self-efficacy, mindfulness skills, and attention focusing and shifting. These results are contrary to our hypotheses of greater clinical impact for CBGT vs. MBSR. The only differential improvement was greater reduction in the frequency of subtle avoidance behaviors after CBGT (vs. MBSR). Safety behaviors are considered to maintain social anxiety in persons with SAD (Piccirillo, Dryman, & Heimberg, in press). CBT explicitly discusses the role of avoidance, as well as trains patients to counter avoidance by engaging in and vicariously learning from multiple exposures to feared situations. The frequency of safety behaviors has previously been shown to decrease more following CBT compared to a stress management control (Cuming et al., 2009). Unlike CBT, MBSR does not explicitly address safety behaviors and specifically avoidance behaviors.

The improvement in reappraisal frequency and self-efficacy, and cognitive distortions after MBSR at the same level as CBGT was unexpected. Across studies of mindfulness meditation, there is preliminary evidence for improvement in cognitive distortions (Sears & Kraus, 2009), and increases in mindfulness and emotion regulation, as well as decreases in avoidance of emotional experience (Chiesa, Anselmi, & Serretti, 2014). Overall, the pattern of changes found in this study suggests more similarity then differences for the impact of CBGT and MBSR in adults with SAD.

With regard to mediation, increases in reappraisal frequency, mindfulness skills and attention focusing and shifting, as well as decreases in subtle avoidance and cognitive distortions each mediated the effect of CBGT vs. WL and also MBSR vs WL on social anxiety symptoms. These suggest multiple shared psychological mechanisms of change for both CBT and MBSR that span attention, cognitive and behavioral processes. In contrast, reappraisal self-efficacy and subtle avoidance differentially mediated the impact of CBT (vs. MBSR) on social anxiety symptoms. This result converges with a prior RCT study in which increases in reappraisal self-efficacy mediated the effect of individual CBT for SAD on social anxiety symptoms (Goldin et al., 2012). One explanation of this mediation result is that CBT provides challenging but safe opportunities to face long-held social fears in the context of in-session and in-vivo exposures. The shift in metacognition, namely, awareness of and belief in one's ability to use reappraisal effectively when needed (i.e., reappraisal self-efficacy) is a fundamental learning lesson in CBT and likely contributes to social anxiety symptom reduction.

Decreases in subtle avoidance and cognitive distortions both mediated the impact of CBGT and MBSR (vs. WL). Avoidance and cognitive distortions have been found to be mediators of CBT for SAD (Hedman et al., 2013; Smits et al., 2006) and accords with cognitive behavioral models of SAD. What is more novel is that reductions in avoidance and cognitive distortion mediated the impact of MBSR at the same level of CBGT. One key component of MBSR training which may account for the reduction in avoidance behaviors is the emphasis on radical acceptance of experience. While there is one study showing evidence for cognitive distortions as a mediator of mindfulness-based interventions (Gu et al., 2015), it is not yet clear whether CBT and MBSR arrive at reduction in cognitive distortions via different underlying mechanisms.

Contrary to our prediction, increases in attention focusing and shifting mediated the effect of CBGT and MBSR (vs. WL). This suggests that both CBT and MBSR may increases executive ability to direct attention albeit via different types of training methods. Enhanced attention regulation may be one shared mechanism by which both CBT and MBSR helps adults with SAD to modify overlearned attentional biases and flexibly shift between threat and non-threat stimuli. Although enhancement of mindfulness skills during CBT may be, at first glance, surprising, this is not a novel finding. Changes in mindfulness have been found to be a mediator of MBSR and MBCT across clinical samples (Gu et al., 2015), and specifically in patients with generalized anxiety disorder (Hoge et al., 2015).

These results highlight the many shared underlying psychological processes that are modulated during CBT and MBSR and may help explain why both are equivalently effective for SAD. The clinical implications of this study are that both CBT and MBSR are efficacious treatments for adults with SAD. They have both shared and unique changes in underlying psychological processes that mediate or predict treatment outcome. This provides clinicians and clinics with stronger confidence in integrating MBSR into their set of interventions to treat SAD.

Limitations

It is important to note that the 56.5% of the patient sample were non-white (39% Asian American, 9% Latino American, 6.5% multiple ethnicities, 1% African American, 1% Native American). Although there was significant ethnic diversity, there was underrepresentation of African-Americans in this sample. However, there was a wide range of socioeconomic status as indicated by yearly income. Thus, these results are highly generalizable.

The focus of this study was on the effects of CBGT vs. MBSR (vs. WL) on traditional outcomes and treatment-related psychological processes in adults with generalized SAD. Our study could be strengthened by the inclusion of computer tasks to complement traditional outcome indices (e.g., implicit association test) and putative mechanisms (e.g., attentional control measures). In an attempt to balance the frequency and dose of treatments in our study, MBSR was modified slightly from its standard implementation. It is possible that inclusion of the one-day silent retreat could have improved MBSR outcomes. Furthermore, community-based MBSR groups are typically larger and include individuals with a more diverse set of presenting problems. Similarly, the current results apply only to group therapy and future research should examine whether the results replicate in the context of individual CBT and MBSR, particularly given that mechanisms may differ between individual and group formats (Hedman et al., 2013).

Finally, experimental dismantling studies are needed to examine whether hypothesized treatment-specific mechanisms, such as cognitive reappraisal and mindfulness, differentially change (and mediate improvements) following implementation of treatment-specific techniques (e.g., cognitive restructuring vs. mindful breath awareness). It may be that the essential “ingredients” in practice are an ability to (1) distance oneself from one's thoughts, whether through questioning the evidence consistent with a troubling thought or through decentering, and (2) approach previously-avoided situations, whether as an attempt to gather disconfirmatory information about these situations or engage in valued action.

Table 2. Treatment Outcome and Process Measures.

| Variable | CBGT Mean (SD) (n = 36) | MBSR Mean (SD) (n = 36) | WL Mean (SD) (n = 36) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | |||

| Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale - SR | |||

| Baseline | 91.8 (17.9) | 91.9 (19.9) | 88.3 (16.1) |

| Post-Tx/WL | 49.0 (16.3) | 54.8 (18.6) | 76.2 (22.8) |

| Within-group effect | t(35)=10.4***, d=1.74 | t(35)=10.7***, d=1.79 | t(35)=5.3***, d=0.88 |

| Treatment-Related Processes | |||

| Cognitive Reappraisal Frequency | |||

| Baseline | 3.7 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.9 (1.4) |

| Post-Tx/WL | 4.8 (0.8) | 4.8 (0.8) | 4.3 (1.4) |

| Within-group effect | t(30)=4.5***, d=0.81 | t(26)=5.2***, d=1.01 | t(33)=2.4*, d=0.41 |

| Cognitive Reappraisal Self-Efficacy | |||

| Baseline | 3.5 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.3) | 4.0 (1.4) |

| Post-Tx/WL | 4.9 (0.9) | 4.4 (1.0) | 4.2 (1.4) |

| Within-group effect | t(30)=5.3***, d=0.95 | t(26)=3.1**, d=0.60 | t(33)=0.7, d=0.11 |

| Subtle Avoidance | |||

| Baseline | 83.0 (18.1) | 83.5 (16.8) | 88.4 (20.9) |

| Post-Tx/WL | 62.9 (13.7) | 73.7 (16.1) | 87.4 (21.7) |

| Within-group effect | t(29)=5.7***, d=1.03 | t(26)=2.9**, d=0.55 | t(33)=0.5, d=0.09 |

| Cognitive Distortions | |||

| Baseline | 28.2 (16.5) | 30.2 (15.2) | 32.8 (14.9) |

| Post-Tx/WL | 19.1 (10.7) | 21.9 (13.5) | 31.8 (16.6) |

| Within-group effect | t(29)=2.9**, d=0.53 | t(26)=3.8**, d=0.73 | t(33)=0.5, d=0.09 |

| Mindfulness Skills | |||

| Baseline | 109.1 (16.5) | 105.7 (14.9) | 110.8 (16.1) |

| Post-Tx/WL | 123.5 (15.9) | 123.3 (22.4) | 105.2 (15.2) |

| Within-group effect | t(30)=5.6***, d=1.00 | t(27)=4.3***, d=0.80 | t(33)=3.4**, d=0.58 |

| Attention Focusing | |||

| Baseline | 22.3 (4.4) | 22.6 (6.1) | 22.3 (5.0) |

| Post-Tx/WL | 23.3 (5.4) | 23.7 (5.6) | 21.5 (5.9) |

| Within-group effect | t(30)=1.3, d=0.23 | t(27)=1.7, d=0.31 | t(33)=1.7, d=0.29 |

| Attention Shifting | |||

| Baseline | 23.1 (3.6) | 24.1 (4.8) | 23.5 (5.1) |

| Post-Tx/WL | 24.6 (4.8) | 24.6 (4.8) | 22.6 (4.6) |

| Within-group effect | t(30)=1.8, d=0.33 | t(27)=0.8, d=0.16 | t(33)=1.7, d=0.28 |

| Rumination | |||

| Baseline | 13.3 (3.8) | 13.4 (3.7) | 13.4 (3.3) |

| Post-Tx/WL | 10.4 (3.9) | 11.9 (4.2) | 13.7 (3.3) |

| Within-group effect | t(29)=4.3***, d=0.77 | t(26)=1.7, d=0.32 | t(33)=-0.5, d=0.08 |

Note. CBGT = cognitive-behavioral group therapy, MBSR = mindfulness-based stress reduction, WL = waitlist, Tx = treatment, d = Cohen's d effect size measure, Pre vs. post within-group change

p < .01,

p < .005,

p < .001

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an NIMH Grant R01 MH076074, awarded to James Gross, Ph.D. Richard Heimberg, Ph.D. is the author of the commercially available group CBT protocol which was utilized in this study.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02036658

None of the authors of this manuscript have any other financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Acarturk C, Graaf R, Straten A, ten Have M, Cuijpers P. Social phobia and number of social fears, and their association with comorbidity, health-related quality of life and help seeking. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2008;43(4):273–279. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acarturk C, Smit F, de Graaf R, van Straten A, ten Have M, Cuijpers P. Economic costs of social phobia: A population-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;115(3):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13:27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Xu Y, Schneier FR, Okuda M, Liu SM, Heimberg RG. Predictors of persistence of social anxiety disorder: a national study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45:1557–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.08.004. doi:S0022-3956(11)00175-0[pii]10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, John OP, Goldin PR, Werner K, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. The role of maladaptive beliefs in cognitive-behavioral therapy: Evidence from social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012;50:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.02.007. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozovich FA, Goldin P, Lee I, Jazaieri H, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. The effect of rumination and reappraisal on social anxiety symptoms during cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2015;71:208–218. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Anselmi R, Serretti A. Psychological mechanisms of mindfulness-based interventions: What do we know? Holistic Nursing Practice. 2014;28:124–148. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Niles AN, Burklund LJ, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Vilardaga JCP, Arch JJ, et al. Lieberman MD. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for social phobia: Outcomes and moderators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;82:1034–1048. doi: 10.1037/a0037212. doi:10.1037.a0037212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuming S, Rapee RM, Kemp N, Abbott MJ, Peters L, Gaston JE. A self-report measure of subtle avoidance and safety behaviors relevant to social anxiety: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:879–883. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira IR. Introducing the Cognitive Distortions Questionnaire. In: De Oliveira IR, editor. Trial-based Cognitive Therapy: A manual for clinicians. New York: Routledge; 2015. pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Reed MA. Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:225–236. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L) New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Coles ME, Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hami S, Stein MB, Goetz D. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: a comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formats. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:1025–1035. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701004056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin P, Ziv M, Jazaieri H, Gross JJ. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction versus aerobic exercise: Effects on the self-referential brain network in social anxiety disorder. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012;6:295. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin P, Ziv M, Jazaieri H, Hahn K, Gross JJ. MBSR vs aerobic exercise in social anxiety: fMRI of emotion regulation of negative self-beliefs. Social, Cognitive Affective Neuroscience. 2013;8:65–72. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion. 2010;10:83–91. doi: 10.1037/a0018441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Jazaieri H, Ziv M, Kraemer H, Heimberg R, Gross JJ. Changes in positive self-views mediate the effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1:301–310. doi: 10.1177/2167702613476867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Lee I, Ziv M, Jazaieri H, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. Trajectories of change in emotion regulation and social anxiety during cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;56:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Manber-Ball T, Werner K, Heimberg R, Gross JJ. Neural mechanisms of cognitive reappraisal of negative self-beliefs in social anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Ziv M, Jazaieri H, Werner K, Kraemer H, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. Cognitive reappraisal self-efficacy mediates the effects of individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:1034–1040. doi: 10.1037/a0028555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K. How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;37:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hedman E, Mörtberg E, Hesser H, Clark DM, Lekander M, Andersson E, Ljótsson B. Mediators in psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: Individual cognitive therapy compared to cognitive behavioral group therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013;51:696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Becker RE. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia: Basic mechanisms and clinical strategies. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffart A, Borge FM, Sexton H, Clark DM. Change processes in residential cognitive and interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia: a process-outcome study. Behavior Therapy. 2009;40:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Cognitive mediation of treatment change in social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:393–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge EA, Bui E, Goetter E, Robinaugh DJ, Ojserkis RA, Fresco DM, Simon NM. Change in Decentering Mediates Improvement in Anxiety in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2015;39:228–235. doi: 10.1007/s10608-014-9646-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope D, Heimberg R, Turk C. Managing Social Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach. 2nd. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Roberts LJ, Berns SB, McGlinchey JB. Methods for defining and determining the clinical significance of treatment effects: Description, application, and alternatives. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:300. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocovski NL, Fleming JE, Hawley LL, Ho MHR, Antony MM. Mindfulness and acceptance-based group therapy and traditional cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: Mechanisms of change. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;70:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocovski NL, Fleming JE, Hawley LL, Huta V, Antony MM. Mindfulness and acceptance-based group therapy versus traditional cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: Arandomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013;51:889–898. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koszycki D, Benger M, Shlik J, Bradwejn J. Randomized trial of a meditation-based stress reduction program and cognitive behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2518–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A, Potter C, Carper M, Kinner D, Jensen D, Bruce L, et al. Heimberg R. The Cognitive Distortions Questionnaire (CD-Quest): Psychometric properties and exploratory factor analysis. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2015;8:287–305. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2015.8.4.287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niles AN, Burklund LJ, Arch JJ, Lieberman MD, Saxbe D, Craske MG. Cognitive mediators of treatment for social anxiety disorder: Comparing acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Behavior Therapy. 2014;45:664–677. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton AR, Abbott MJ, Norberg MM, Hunt C. A systematic review of mindfulness and acceptance-based treatments for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2015;71:283–301. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsson RP, Smari J, Guethmundsdottir F, Olafsdottir G, Harethardottir HL, Einarsson SM. Self reported attentional control with the Attentional Control Scale: factor structure and relationship with symptoms of anxiety and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:777–782. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Pollack MH, Maki KM, Gould RA, Worthington JJ, Smoller JW, 3rd, Rosenbaum JF. Childhood history of anxiety disorders among adults with social phobia: Rates, correlates, and comparisons with patients with panic disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;14:209–213. doi: 10.1002/da.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A, Knapp M, Henderson J, Baldwin D. The economic consequences of social phobia. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;68(2-3):221. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccirillo ML, Dryman MT, Heimberg RG. Safety behaviors in adults with social anxiety: Review and future directions. Behavior Therapy. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.11.005. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MB, Sigmarsson SR, Emmelkamp PMG. A meta-analytic review of psychological treatments for social anxiety disorder. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2008;1:94–113. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2008.1.2.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rytwinski NK, Fresco DM, Heimberg RG, Coles ME, Liebowitz MR, Cissell S, et al. Hofmann SG. Screening for social anxiety disorder with the self-report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:34–38. doi: 10.1002/da.20503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears S, Kraus S. I think therefore I om: Cognitive distortions and coping style as mediators for the effects of mindfulness meditation on anxiety, positive and negative affect, and hope. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:561–573. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JAJ, Rosenfield D, McDonald R, Telch MJ. Cognitive mechanisms of social anxiety reduction: An examination of specificity and temporality. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1203–1212. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl B, Goldstein E. A mindfulness-based stress reduction workbook. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tang YY, Hölzel BK, Posner MI. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2015;16:213–225. doi: 10.1038/nrn3916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Segal Z, Williams JMG. How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:25–39. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)E0011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]