Abstract

Introduction

Adult Medicaid enrollees are more likely to have mental health disorders (MHD) than privately insured patients and also have high rates of Emergency Department (ED) visits for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions (ACSC). We aimed to evaluate the association of MHD and insurance type with ED admissions for ACSC in the U.S.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of ED visits made by adults aged 18–64 years using the corrected 2011 National Emergency Department Survey (NEDS). Using multivariable logistic regression analysis, we controlled for socio-demographics and clinical variables to determine the association between insurance type, MHD, Medicaid and MHD (as an interaction variable) and ED admissions for ACSC.

Results

There were 131 million ED visits in 2011; after exclusions, 1.4 million admissions were included in our study. Of all ED visits, 44.7% had a MHD, of which 49.9% were covered by Medicaid and 38.1% were covered by private insurance. A total of 32.6% (95% CI 32.5%–32.7%) of ED admissions were for an ACSC (Table 1). Medicaid covered ED visits were more likely to result in ACSC hospital admission (OR 1.32; 95% CI 1.30–1.35) compared to visits covered by private insurance. Among patients with MHD, those with Medicaid insurance had 1.6 times the odds of ACSC admission compared to those privately insured.

Conclusion

Among all ED admissions, patients covered by Medicaid are more likely to be admitted for an ACSC when compared to those covered by private insurance, with a larger association being present among patients with MHD co-morbidities.

Keywords: Mental Health Disorders, Insurance, Medicaid, Hospital Admissions, Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions

INTRODUCTION

Millions of Americans suffer from co-occurring mental and physical chronic illness.1, 2 Adults with mental health disorders (MHD) are less likely to care for their chronic medical conditions and have worse outcomes of co-occurring chronic diseases compared to patients without MHD.3 They are also more likely to have frequent visits to the Emergency Department (ED) and to be admitted.4–7 States throughout the U.S. are developing interventions aimed at reducing costs by preventing avoidable hospital admissions. Ambulatory care sensitive condition (ACSC) hospital admissions are a nationally recognized quality measure used to identify avoidable hospital admissions.8

Patients insured by Medicaid are more likely to have MHD and to present to the ED with chronic medical disease complaints.9–11 Specifically, adult Medicaid enrollees have higher rates of ACSC ED visits compared to those privately insured and uninsured.12 Survey studies suggest that patients with Medicaid utilize the ED more often when compared with those who have private insurance because of primary care access barriers.13 However, those studies were limited in that they did not 1) evaluate hospital admissions from the ED for ACSC and 2) take into account whether or not Medicaid enrollees had a MHD diagnosis, and how this could potentially impact their care for co-occurring chronic diseases.

Previous studies conducted on the elderly population and veterans showed a strong link between MHD and hospital admissions for ACSC.14, 15 We hypothesize that a similar pattern exists for those with Medicaid insurance. Given the ED is the portal of entry for hospital admissions covered by Medicaid insurance, we used a nationally representative all payer ED dataset to evaluate whether an interaction exists between MHD and Medicaid insurance coverage when evaluating patients admitted from the ED for an ACSC. Understanding the role of MHD and insurance type on ACSC admissions from the ED has important clinical and policy implications, especially given Medicaid is now the largest payer source for low income Americans.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional study of adults aged 18 to 64 years using the corrected 2011 National Emergency Department Survey (NEDS). The corrected version accounts for errors found in the prior NEDS 2011 database. We included individuals that were admitted to the hospital from the ED or those that were transferred, as patients that are transferred are usually admitted to the hospital. NEDS is a part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Program (HCUP), which is the largest US collection of data related to longitudinal hospital care.16 The dataset provides patient level data on a 20% stratified sample of ED visits, from 950 hospitals and 30 states, which are used to generate nationally representative estimates. For the year of 2011, it had approximately 131 million ED visits.17 Hospitals are selected using a stratified probability sample based on geographic region, trauma designation, urban-rural location, teaching status, and hospital control in order to provider an accurate estimate of the total number of ED visits that occur in U.S. The NEDS is publically available through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Primary Outcome

Our primary outcome was hospital admissions from the ED for ACSC among patients with MHD and Medicaid when compared to patients with MHD or Medicaid alone.

Study Patient Population

We defined MHD by applying MHD Clinical Classification Software (CCS) groupings (650–652, 656–659, 663 and 670) to NEDS diagnostic fields 2–15. These numbers correspond to the following MHD: adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, attention-deficit, conduct and disruptive behavior disorders, impulse control disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, screening and history of mental health and substance abuse codes, miscellaneous mental disorders (eating disorders, mental disorders in pregnancy, dissociative disorders, factitious disorders, sleep disorders, and somatoform disorders). We excluded substance abuse and mental health disorders of infancy, given our goal was to focus on mental health disorders, including mood, personality, adjustment, anxiety, impulse and behavioral disorders in the adult population.

Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions were defined using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) definition.8 The following conditions are included in the analysis: bacterial pneumonia, hypertension, dehydration, adult asthma, urinary tract infection, chronic-obstructive pulmonary disease, perforated appendix, diabetes short-term complication, diabetes long-term complication, uncontrolled diabetes, lower extremity amputation among patients with diabetes, angina without procedure, and congestive heart failure. We excluded all conditions pertaining to the pediatric population, such as pediatric gastroenteritis, pediatric asthma, and low birth weight.

From the 131 million ED visits in the NEDS database, we excluded 110 million as they did not lead to a hospital admission. From this population, we excluded patients with a primary admission diagnosis of MHD, as we wanted to evaluate the impact of MHD on admissions primarily for ACSC from the ED. We also excluded those who were admitted to the hospital from the ED primarily for an injury, as these are more likely a result of trauma and not a chronic disease. Patients who were pregnant or who died in the ED were also excluded. Finally, we excluded those with Medicare insurance as these patients are more likely to be chronically ill and disabled, and not comparable with our remaining sample. After all exclusions, we had 1.5 million ED visits in our study, which was equivalent to 6.5 million once weighted. We categorized insurance status by Medicaid, private, self-pay, or other. Using the NEDS database, we also collected information on patients’ gender, income, and zip codes.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to calculate the mean along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for baseline descriptive characteristics. We performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis controlling for socio-demographics and medical co-morbidities to determine the association between insurance type, presence of MHD, and ED admissions for ACSC. In order to determine if MHD modifies the relationship between Medicaid insurance and ED admissions for ACSC, we created an interaction variable (Medicaid*MHD). We report odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI for variables included in the multivariate logistic regression model. We applied SURVEY commands to account for the complex survey design and provide national estimates. All data analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 131 million ED visits in the year of 2011. Of these, there were 6.5 million admissions from the ED and, after applying our exclusion criteria, 1.4 million admissions were included in our study. The patient characteristics of those individuals, weighted as a total and separated by ACSC vs. non-ACSC admission, are listed in Table 1. Individuals between the ages of 45 and 64 made up the majority of admissions (29.55%, 95% CI 29.48–29.63 and 31.45%, 95% CI 31.37–31.53, respectively). Half of the admitted population was female (49.96%, 95% CI 49.88–50.04). A slightly higher, but statistically significant, portion of the population with a MHD was admitted for an ACSC (46.04%, 95% CI 45.89–46.19) compared with a non-ACSC (43.97%, 95% CI 43.87–44.07).

Table 1.

Population Characteristics

| Characteristic | Hospital Admission | Total Admission | Total Admission 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACSC (W1 %) | ACSC 95% CI | Non-ACSC | Non-ACSC 95% CI | |||

| N=472046 (W=2104909) | -- | N=970376 (W=4347328) | -- | N=1442422 (W=6452237) | -- | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18–24 | 4.61 | 4.55–4.67 | 9.18 | 9.12–9.23 | 7.69 | 7.64–7.73 |

| 25–34 | 8.26 | 8.18–8.35 | 15.70 | 15.63–15.78 | 13.28 | 13.22–13.33 |

| 35–44 | 15.15 | 15.05–15.26 | 19.43 | 19.35–19.51 | 18.04 | 17.97–18.10 |

| 45–54 | 31.70 | 31.56–31.84 | 28.51 | 28.42–28.60 | 29.55 | 29.48–29.63 |

| 55–64 | 40.27 | 40.13–40.42 | 27.18 | 27.08–27.27 | 31.45 | 31.37–31.53 |

| Gender (female) | 50.80 | 50.65–50.94 | 49.55 | 49.45–49.66 | 49.96 | 49.88–50.04 |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Medicaid | 36.26 | 36.11–36.40 | 28.25 | 28.16–28.35 | 30.86 | 30.79–30.94 |

| Private | 41.68 | 41.53–41.82 | 48.44 | 48.34–48.54 | 46.23 | 46.15–46.32 |

| Self-Pay | 16.67 | 16.56–16.78 | 17.99 | 17.91–18.07 | 46.23 | 46.15–46.32 |

| Other | 5.40 | 5.33–5.47 | 5.31 | 5.27–5.36 | 5.34 | 5.31–5.38 |

| Patient Location | ||||||

| “Central” counties of metro areas of ≥1 million population | 32.97 | 32.84–33.09 | 32.69 | 32.61–32.77 | 32.78 | 32.73–32.84 |

| “Fringe” counties of metro areas of ≥1 million population | 23.45 | 23.33–23.56 | 25.36 | 25.29–25.44 | 24.74 | 24.68–24.79 |

| Counties in metro areas of 250,000–999,999 population | 19.63 | 19.63–19.74 | 19.33 | 19.27–19.40 | 19.43 | 19.39–19.47 |

| Counties in metro areas of 50,000–249,999 population | 8.30 | 8.22–8.38 | 7.68 | 7.63–7.73 | 7.89 | 7.85–7.92 |

| Micropolitan counties | 9.56 | 9.49–9.64 | 9.06 | 9.01–9.10 | 9.22 | 9.19–9.25 |

| Not metropolitan or micropolitan counties | 6.10 | 6.03–6.16 | 5.87 | 5.83–5.91 | 5.94 | 5.92–5.97 |

| Zip Code Quartile | ||||||

| 0–25th percentile | 32.23 | 32.09–32.36 | 26.44 | 26.35–26.52 | 28.33 | 28.26–28.40 |

| 26th to 50th percentile | 24.56 | 24.44–24.69 | 23.08 | 22.99–23.16 | 23.56 | 23.49–23.63 |

| 51st to 75th percentile | 23.19 | 23.07–23.31 | 24.69 | 24.61–24.78 | 24.20 | 24.13–24.27 |

| 76th to 100th percentile | 16.83 | 16.73–16.94 | 22.47 | 22.39–22.55 | 20.63 | 20.57–20.6 |

| Missing | 3.19 | 3.14–3.24 | 3.33 | 3.29–3.36 | 3.28 | 3.25–3.31 |

| Mental Health Disorder2 | 46.04 | 45.89–46.19 | 43.97 | 43.87–44.07 | 44.65 | 44.57–44.73 |

| Comorbid Condition | ||||||

| Diabetes | 70.82 | 70.68–70.95 | 2.47 | 2.44–2.50 | 24.77 | 24.69–24.84 |

| HTN3 | 61.39 | 61.25–61.53 | 32.48 | 32.39–32.58 | 41.91 | 41.83–41.99 |

| CAD4 | 22.36 | 22.34–22.48 | 11.32 | 11.25–11.38 | 14.92 | 14.86–14.98 |

| COPD5 | 14.96 | 14.86–15.07 | 8.28 | 8.23–8.34 | 10.46 | 10.41–10.51 |

| CKD6 | 12.32 | 12.22–12.42 | 3.71 | 3.67–3.75 | 6.52 | 6.48–6.56 |

| Cancer | 8.13 | 8.05–8.21 | 10.72 | 10.66–10.79 | 9.88 | 9.83–9.93 |

| CHF7 | 2.45 | 2.40–2.49 | 2.94 | 2.91–2.97 | 2.78 | 2.75–2.81 |

Weighted total,

Presence of Mental Health Disorder,

HTN=Hypertension,

CAD=Coronary Artery Disease,

COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease,

CKD=Chronic Kidney Disease,

CHF=Congestive Heart Failure

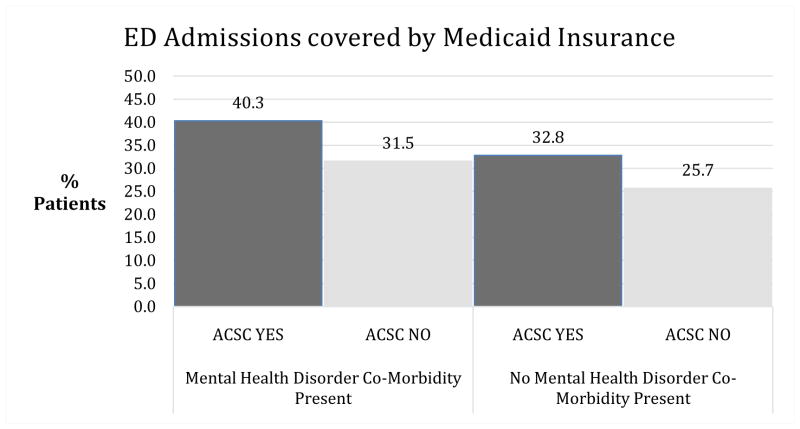

Using an adjusted logistic regression analysis for confounders, there was an interaction between insurance and MHD in association with admission for an ACSC (p<0.001; Figure 1). Medicaid patients without MHD had increased odds of being admitted for an ACSC compared to patients with private insurance and no MHD (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.31–1.35). Among admissions listing MHD as a co-morbidity, those covered by Medicaid were 1.41 times more likely to be for an ACSC compared to privately insured patients.

Figure 1.

Insurance status by presence of MHD and ACSC

A total of 32.6% (95% CI 32.5%–32.7%) of ED admissions were for an ACSC. After controlling for confounding factors, this population was more likely to be 55–64 years of age than younger, more likely to be female, more likely to be insured by Medicaid, self-pay or other compared to privately insured, and more likely to have a lower income (Table 2).

Table 2.

Odds of Admission for an Ambulatory Care Sensitive Condition by Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | OR for ACSC N=215464 (W=969103) |

95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 0.70* | 0.69–0.72 |

| 25–34 | 0.60* | 0.59–0.61 |

| 35–44 | 0.68* | 0.67–0.69 |

| 45–54 | 0.83* | 0.81–0.84 |

| 55–64 | REFERENCE | |

| Gender (female) | 1.23* | 1.22–1.25 |

| Patient Location | ||

| “Central” counties of metro areas of ≥1 million population | REFERENCE | |

| “Fringe” counties of metro areas of ≥1 million population | 1.09* | 1.07–1.11 |

| Counties in metro areas of 250,000–999,999 population | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 |

| Counties in metro areas of 50,000–249,999 population | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 |

| Micropolitan counties | 1.12* | 1.10–1.14 |

| Not metropolitan or micropolitan counties | 1.19* | 1.17–1.22 |

| Zip Code Quartile | ||

| 0–25th percentile | REFERENCE | |

| 26th to 50th percentile | 0.90* | 0.89–0.91 |

| 51st to 75th percentile | 0.82* | 0.80–0.83 |

| 76th to 100th percentile | 0.71* | 0.70–0.72 |

| Missing | 0.86 | 0.83–0.89 |

| Insurance Type1 | ||

| Medicaid | 1.33* | 1.31–1.35 |

| Private | REFERENCE | |

| Self-Pay | 1.31* | 1.28–1.33 |

| Other | 1.12* | 1.09–1.16 |

| MHD by Insurance Type2 | ||

| Medicaid | 1.22* | 1.20–1.24 |

| Private | 1.15* | 1.13–1.17 |

| Comorbid Condition | ||

| Diabetes | 91.68* | 90.24–93.14 |

| HTN3 | 1.46* | 1.45–1.48 |

| CAD4 | 1.28* | 1.26–1.30 |

| COPD5 | 2.91* | 2.87–2.96 |

| CKD6 | 1.66* | 1.62–1.69 |

| Cancer | 0.70* | 0.69–0.72 |

| CHF7 | 0.29* | 0.28–0.30 |

| Interaction Variable | ||

| Medicaid for MHD | 1.41* | 1.38–1.44 |

| Self-pay for MHD | 1.32* | 1.25–1.39 |

| Other for MHD | 1.04 | 0.99–1.08 |

Corresponds to a p-value <0.001,

Corresponds to OR when no MHD present,

Patients with co-morbid Mental Health Disorder,

HTN=Hypertension,

CAD=Coronary Artery Disease,

COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease,

CKD=Chronic Kidney Disease,

CHF=Congestive Heart Failure

Certain mental health disorders were more likely to be associated with admission to the hospital for ACSC than others (Table 3). The presence of an anxiety disorder, mood disorder, or history of a mental health disorder was more closely associated with admission in relation to other mental health disorders.

Table 3.

Mental Health Disorders (MHD) Percentage among Ambulatory Care Sensitive Condition (ASCS) Admissions

| Mental Health Disorder | ACSC % N=215464 (W=969103) |

ACSC 95% CI2 |

|---|---|---|

| Screening and history of mental health | 24.06 | 23.95–24.17 |

| Mood Disorder | 11.15 | 11.06–11.22 |

| Anxiety Disorder | 5.14 | 5.19–15.27 |

| Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders | 1.41 | 1.38–1.44 |

| Suicidal Ideation | 0.29 | 0.27–0.30 |

| Attention-Deficit Disorder, conduct and disruptive behavior disorder | 0.28 | 0.26–0.30 |

| Miscellaneous | 0.22 | 0.21–0.24 |

| Adjustment Disorder | 0.21 | 0.20–0.22 |

| Personality Disorder | 0.20 | 0.19–0.21 |

| Disorders usually diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence | 0.05 | 0.04–0.05 |

| Impulse Control Disorder, NEC | 0.01 | 0.01–0.02 |

Confidence Interval for Proportions

Lastly, lower-extremity amputation from a diabetic complication was the leading cause of admission for both individuals with (29.72%) and without a MHD (39.46%) (Appendix 1). COPD was the next highest admission for individuals with MHD with 5.03% of the MHD population admitted for this diagnosis, while only 1.24% of individuals without MHD were admitted for COPD. The remaining admission diagnoses by presence or absence of MHD are presented in Appendix 1.

Appendix 1.

Ambulatory Care Sensitive Condition (ASCS) Admission Diagnoses

| ACSC Admission Diagnosis | MHD N =215464 W=969103 |

MHD 95% CI --- |

No MHD N =256582 W=625608 |

MHD 95% CI -- |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower-extremity amputation among patients with diabetes | 29.72 | 29.59–29.86 | 39.45 | 39.30–39.59 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 5.05 | 4.99–5.11 | 1.25 | 1.21–1.28 |

| Bacterial Pneumonia | 4.90 | 4.84–4.96 | 4.55 | 4.49–4.62 |

| Adult Asthma | 3.49 | 3.43–3.54 | 2.68 | 2.63–2.72 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 2.79 | 2.74–2.84 | 3.58 | 3.53–3.64 |

| Diabetes short-term complication | 2.49 | 2.44–2.53 | 2.97 | 2.93–3.03 |

| Diabetes long-term complication | 1.60 | 1.57–1.64 | 2.55 | 2.51–2.60 |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 1.93 | 1.89–1.97 | 3.11 | 3.05–3.16 |

| Hypertension | 1.34 | 1.31–1.37 | 1.69 | 1.65–1.72 |

| Dehydration | 0.69 | 0.67–0.72 | 0.90 | 0.88–0.93 |

| Angina without procedure | 0.63 | 0.61–0.66 | 0.88 | 0.85–0.90 |

| Perforated Appendix | 0.52 | 0.50–0.54 | 1.35 | 1.32–1.39 |

| Uncontrolled diabetes | 0.45 | 0.43–0.47 | 0.57 | 0.55–0.59 |

DISCUSSION

In this national study, we found that although patients with Medicaid have higher rates of ACSC admission when compared with those who are privately insured, even higher rates are seen for those who also have MHD. Our study is novel in that we investigate the interaction between MHD and Medicaid insurance. This interaction suggests MHD is an important co-morbidity to evaluate when assessing avoidable ED utilization and developing interventions that reduce avoidable hospital admissions.

Medicaid enrollees are among those with less socioeconomic resources, with complex medical problems or in many cases, both. Low-income individuals with chronic health problems have a high likelihood of MHD.18, 19 As such, the interaction of MHD, chronic medical problems and socioeconomic status would seem to have an intimate and deeply intertwined role. These factors are likely linked with the inability to make or keep a primary care appointment or to navigate the system further to receive mental health help.

Interestingly, the most common ACSC admissions for those with MHD were related to respiratory conditions, specifically asthma and COPD. Studies show a significant relationship between respiratory disorders and anxiety and depression.20–22 The feeling of dyspnea, which is often the chief complaint associated with an ED visit for a respiratory condition, can invoke a strong feeling of anxiety. This feeling may persist after treatment has been implemented and become a regular part of a patient’s life. Over time, a respiratory condition may decrease quality of life, both from a functional and mental standpoint, and patients may subsequently develop depression. Alternatively, those individuals with existing MHD may also have a more difficult time adhering to outpatient management of respiratory disorders,23 which may increase their likelihood of presenting to the ED and being admitted for treatment.

Although we cannot explain why the interaction between MHD and Medicaid exists in association with ACSC ED admissions, we believe that improving access to behavioral health and primary care services may be the key to decreasing ACSC hospital admissions from the ED. Because Medicaid enrollees have a difficult time accessing primary care services, adding mental health evaluations in the ED (i.e., PQH9), may help to identify those patients at most need of intensive outpatient mental health follow-up. In addition, implementing reform to integrate primary care visits with mental health visits may provide the needed support for these patients to function and help treat their comorbid illnesses in the outpatient setting.24, 25 At the very least, more studies need to be completed to evaluation and understand this interaction.

Our study is limited in that it is a retrospective cross-sectional study using hospital claims data. Due to the nature of the study design, we can only conclude there is an association, not causation, between Medicaid patients with MHD and subsequent ACSC hospital admission from the ED. Additionally, it is possible that because we used claims data that we are under-detecting those with MHD, which could potentially alter our results. On a more fundamental level, we were unable to evaluate the impact of race and ethnicity, as these variables are not available in NEDS. The data also does not distinguish repeat visits from new visits, so high utilizers of the ED could not be identified. Lastly, we are unable to assess primary care and mental health access for these patients.

As the nation moves forward with assessing ways to decrease health care costs, identifying the patient populations that are more likely to be admitted to the hospital for avoidable medical problems is a key improvement measure. Using national data, our study highlights the importance of accounting for Medicaid and MHD as potential drivers for avoidable hospital admissions. While previous studies have concluded that barriers to accessing primary care are one explanation for the high ACSC ED visits for Medicaid patients, our study finds that MHD is an important alternative or additional explanation for these visits. Helping these patients overcome the barriers that exist to obtaining appropriate primary care and addressing their mental health needs may improve their health as well as decrease costs for health care nationwide.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Roberta Capp was supported by a Translational NIH K award.

Footnotes

CB, EJC, RC have no conflicts of interest.

This research was presented at the Western SAEM Conference in Tucson, Arizona on March 27th, 2015 and the National SAEM Conference in San Diego, California on May 14th, 2015.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. The vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(1):A14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mental Health and Chronic Diseases. CDC. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: Division of Population Health; 2012. Issue Brief No 2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, et al. Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Medical Directors Council; 2006. www.nasmhpd.org. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hakenewerth AM, Tintinalli JE, Waller AE, et al. Emergency Department Visits by Patients with Mental Health Disorders — North Carolina, 2008–2010. Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2013;62(23):469–472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, et al. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM. 2008;21(5):398–407. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi NG, Marti CN, Bruce ML, et al. Relationship between depressive symptom severity and emergency department use among low-income, depressed homebound older adults aged 50 years and older. BMC psychiatry. 2012;12:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAlpine DD, Mechanic D. Datapoints: payer source for emergency room visits by persons with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric services. 2002;53(1):14. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AHRQ Quality Indicators—Guide to Prevention Quality Indicators: Hospital Admission for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001. AHRQ Pub. No. 02–R0203. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taubman SL, Allen HL, Wright BJ, et al. Medicaid increases emergency-department use: evidence from Oregon’s Health Insurance Experiment. Science. 2014;343(6168):263–268. doi: 10.1126/science.1246183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pukurdpol P, Wiler JL, Hsia RY, et al. Association of Medicare and Medicaid insurance with increasing primary care-treatable emergency department visits in the United States. Academic emergency medicine: official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2014;21(10):1135–1142. doi: 10.1111/acem.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas MR, Waxmonsky JA, Gabow PA, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders and costs of care among adult enrollees in a Medicaid HMO. Psychiatric services. 2005;56(11):1394–1401. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.11.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsia RY, Brownell J, Wilson S, et al. Trends in adult emergency department visits in California by insurance status, 2005–2010. Jama. 2013;310(11):1181–1183. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.228331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oster A, Bindman AB. Emergency department visits for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: insights into preventable hospitalizations. Medical care. 2003;41(2):198–207. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000045021.70297.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharya R, Shen C, Sambamoorthi U. Depression and ambulatory care sensitive hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic physical conditions. General hospital psychiatry. 2014;36(5):460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoon J, Yano EM, Altman L, et al. Reducing costs of acute care for ambulatory care-sensitive medical conditions: the central roles of comorbid mental illness. Medical care. 2012;50(8):705–713. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824e3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.HCUP NEDS Database Documentation. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Dec, 2014. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/neds/nedsdbdocumentation.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Apr, 2015. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/data/hcup/index.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas J, Jones G, Scarinci I, et al. A descriptive and comparative study of the prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in low-income adults with type 2 diabetes and other chronic illnesses. Diabetes care. 2003;26(8):2311–2317. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones DR, Macias C, Barreira PJ, et al. Prevalence, severity, and co-occurrence of chronic physical health problems of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric services. 2004;55(11):1250–1257. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egede LE. Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. General hospital psychiatry. 2007;29(5):409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Yelin EH, et al. Influence of anxiety on health outcomes in COPD. Thorax. 2010;65(3):229–234. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.126201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filipowski M, Bozek A, Kozlowska R, et al. The influence of hospitalizations due to exacerbations or spontaneous pneumothoraxes on the quality of life, mental function and symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with COPD or asthma. The Journal of asthma: official journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma. 2014;51(3):294–298. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.862543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turan O, Yemez B, Itil O. The effects of anxiety and depression symptoms on treatment adherence in COPD patients. Primary health care research & development. 2014;15(3):244–251. doi: 10.1017/S1463423613000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeiss AM, Karlin BE. Integrating mental health and primary care services in the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008;15(1):73–78. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felker BL, Chaney E, Rubenstein LV, et al. Developing effective collaboration between primary care and mental health providers. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(1):12–16. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v08n0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]