Abstract

The current longitudinal study examined Mexican-origin mothers’ cultural characteristics and ethnic socialization efforts as predictors of their adolescent daughters’ ethnic-racial identity (ERI) exploration, resolution, and affirmation. Participants were 193 Mexican-origin adolescent mothers (M age = 16.78 years; SD = .98) and their mothers (M age = 41.24 years; SD = 7.11). Findings indicated that mothers’ familism values and ERI exploration were positively associated with mother-reported ethnic socialization efforts one year later. Furthermore, mothers’ ERI affirmation was a significant positive predictor of adolescents’ ERI affirmation two years later, accounting for adolescents’ ERI affirmation one year earlier. Discussion emphasizes the significance of ERI development among adolescent mothers who are negotiating the normative development of ERI and faced with their new role as parents and cultural socializers of their young children.

Keywords: adolescent mothers, Mexican/Mexican-origin/Latino, enculturation, ethnic/racial socialization, ethnic/racial identity

Ethnic-racial identity (ERI; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014) is a normative developmental task during adolescence that has been positively associated with Latino youths’ adjustment (e.g., Ghavami, Fingerhut, Peplau, Grant, & Wittig, 2011; Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007), but less is known about how parents’ characteristics, especially parents’ own cultural characteristics, inform adolescents’ ERI over time. In addition, little is known about how this process unfolds in specific samples, for example among adolescent mothers who are engaging in the process of ERI and simultaneously facing the tasks of ethnic socialization with their own offspring.

Parenthood can engage parents in the process of thinking about their ethnicity and the role it will play in their child's life (Hughes et al., 2006). During the transition to parenthood, Latina adolescent mothers are experiencing their own ERI development and also considering the values and beliefs they will pass on to their young children (Umaña-Taylor, Updegraff, Jahromi, & Zeiders, 2015). Although one study examined ERI among adolescent mothers, and found that ERI was positively associated with adjustment (Sieger & Renk, 2007), no studies have examined predictors of ERI among adolescent mothers, taking an intergenerational perspective to consider how their own mothers’ characteristics and socialization efforts inform adolescent mothers’ ERI. Given that adolescent mothers rely heavily on their family of origin during the transition to adolescent parenthood (Contreras, Narang, Ikhlas, & Teichman, 2002), the relevance of parents’ own cultural characteristics (e.g., parents’ cultural values, involvement in culture, ERI) and parents’ ethnic socialization efforts may be particularly influential for adolescent mothers’ ERI development; furthermore, adolescents may be particularly attuned to parents’ socialization cues regarding ERI because they are assuming a parenting role and, thus, looking toward their own parents for cues regarding this aspect of socialization.

Understanding the factors that inform ERI development among adolescent mothers may also inform future intervention efforts with this population of young women who have been found to be at-risk for various negative outcomes, such as lower self-esteem and higher depression (Whitman, Borowski, Keogh, & Weed, 2001). Given the positive associations between ERI and adjustment in numerous studies of non-parenting ethnic minority youth (e.g., Costigan, Koryzma, Hua, & Chance, 2010; Schwartz et al., 2007), and in one study of Latina adolescent mothers (Sieger & Renk, 2007), understanding the factors that positively inform adolescent mothers’ ERI may have significant implications for preventive intervention efforts with adolescent mothers that target normative development and positive outcomes.

Finally, a focus on Mexican-origin adolescent mothers is important given that Mexican-origin adolescent females face the highest rates of teenage pregnancy among all racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. (Ventura, Hamilton, & Mathews, 2013), and are negotiating the normative developmental task of ERI while also taking on the role of parent cultural socialization with their young children. As such, the current longitudinal study examined how mothers’ cultural characteristics were associated with mothers’ ethnic socialization practices and with adolescent mothers’ ERI.

Maternal Characteristics, Ethnic Socialization, and Adolescents’ Ethnic-Racial Identity

ERI captures individuals’ beliefs and attitudes about their ethnic-racial group membership, and the processes by which those beliefs and attitudes develop over time (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Guided by Erikson's (1968) ego identity theory and Tajfel's (1981) social identity theory, scholars propose that certain components of ERI reflect process (i.e., mechanisms through which individuals explore and form their ERI), and other components reflect content (i.e., attitudes and beliefs about one's group; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). In particular, ego identity theory (Erikson, 1968) suggests that development proceeds in a series of stages and, during adolescence, individuals mature by creating continuity between how they have defined identity for themselves and how others view them. Erikson (1968) conceived that this is achieved through exploration and commitment to an identity. Extended to ERI as part of normative development, adolescents engage in processes that involve exploration (i.e., actively learning about their ethnic background) and resolution (i.e., gaining a sense about the meaning of ethnicity as part of their self-concept; Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian & Bámaca-Gómez, 2004). In contrast, social identity theory (Tajfel, 1981) has guided the conceptualization of one aspect of ERI content: ERI affirmation, or the affect that one feels toward one's ethnicity (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). Consistent with notions from social identity theory (Tajfel, 1981), positive feelings regarding one's ethnic group membership (i.e., ERI affirmation) enable individuals to maintain a positive sense of self (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). This three-part conceptualization of ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation has been empirically supported by prior work (e.g., Yoon, 2011).

In considering the factors that are associated with ERI, bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) suggests that individuals’ development occurs through interactive, proximal processes that are informed by characteristics of the individuals involved in those processes. An important proximal process among ethnic minority families is ethnic socialization (Hughes et al., 2006), which can include the efforts of the collective members of a family (i.e., familial ethnic socialization), or the efforts of individual members of the family. With respect to the latter, maternal ethnic socialization captures the way in which mothers contribute to ethnic socialization, such as exposing their children to their heritage culture through activities, such as cooking traditional foods and attending cultural celebrations (Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004). A focus on mothers is particularly important for the current study because mothers are viewed as central figures in the lives of adolescent mothers (Brooks-Gunn & Chase-Lansdale, 1995). Thus, it is possible that mothers’ cultural characteristics inform their ethnic socialization efforts with their daughters, which in turn predict adolescents’ ERI. To date, we know little about the antecedents of maternal ethnic socialization.

In this study, we consider three important maternal cultural characteristics for Latinos: familism values, Mexican cultural involvement, and maternal ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation. Familism values are a defining cultural characteristic in Latino families, and represent values regarding a strong investment in and attachment to family (Knight et al., 2010). Mothers who strongly endorse familistic values may be more invested in putting effort into socializing their adolescents about their culture, which has been supported by limited work in this area (Knight et al., 2011). Similarly, another cultural characteristic that was predictive of mothers’ socialization efforts with children was mothers’ involvement in Mexican culture (Knight, Bernal, Garza, & Cota, & Ocampo, 1993). However, this work has tended to be cross-sectional or focused on mothers with young children and early adolescents. Thus, the current study expanded on this prior research by simultaneously examining how various maternal cultural characteristics (i.e., familism values, involvement in Mexican culture, and ERI) were related to mothers’ socialization efforts with their daughters during late adolescence, when identity formation is a particularly salient developmental task and when adolescents were negotiating their new role as parents.

Turning to the relation between ethnic socialization and ERI, a number of prior studies have focused on familial ethnic socialization (which has included mothers’ efforts), and found that it was positively associated with ERI exploration and resolution among adolescents from an ethnically diverse sample, including youth who were White, Latino, Black, Asian, Native American, and multiethnic (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004); Latino adolescents from immigrant families (i.e., Mexico, Guatemala, and El Salvador; Supple, Ghazarian, Frabutt, Plunkett, & Sands, 2006); and Latino adolescents in high school (Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, Bámaca, & Guimond, 2009). However, few studies have examined whether individual family members’ socialization efforts (e.g., mothers) contribute to adolescents’ ERI, and the limited work that has done so has yielded inconsistent findings. For example, with cross-sectional data, maternal ethnic socialization was not directly associated with Black, Latino (Puerto Rican and Dominican), and Chinese early adolescents’ ERI exploration; instead, maternal socialization efforts were indirectly associated with early adolescents’ ERI exploration via early adolescents’ reports of ethnic socialization (Hughes, Hagelskamp, Way, & Foust, 2009). However, using prospective longitudinal data, Knight and colleagues (2011) found that among a community-based sample of Mexican-origin families, maternal ethnic socialization was positively associated with Mexican-origin early adolescents’ ERI exploration and resolution over time; similarly, Else-Quest and Morse (2015) found that caregivers’ ethnic socialization predicted White, African American, Latino, and Asian American adolescents’ ERI exploration and commitment (i.e., resolution). Regarding adolescents’ ERI affirmation, previous work using cross-sectional data has not found this component to be informed by familial (Supple et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004) or maternal ethnic socialization (White, Umaña-Taylor, Knight, & Zeiders, 2011) among Latino families. The current study extends prior work by testing whether maternal ethnic socialization predicted adolescents’ ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation over time.

The Current Study

Guided by bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), it was hypothesized that during adolescents’ pregnancy (Wave 1; W1) mothers’ familism, involvement in Mexican culture, and ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation would be positively associated with maternal ethnic socialization one year later (i.e., W2). In addition, maternal ethnic socialization at W2 was expected to be positively associated with adolescents’ ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation one year later (i.e., W3), after controlling for prior levels of ERI at W2. However, in our model, we also estimated the direct paths from mothers’ ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation to adolescents’ ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation to rule out the possibility that mothers’ ERI may be directly associated with adolescents’ ERI, rather than occurring via mothers’ socialization efforts. Adolescents’ age at W1 and country of birth were included as control variables.

Method

Participants

The current analytic sample included 193 Mexican-origin adolescents and their mother figures (e.g., biological mother, grandmother) from the first three waves of a larger sample of 204 dyads (author citation). The majority of families participated across all six waves of the larger study (i.e., 96% at W2, and 88% at W3, W4, W5, and W6). Because 88% of mother figures were adolescents’ biological mothers, the term “mother” was used for ease of discussion. Eleven dyads were excluded from the larger sample, including eight dyads that were excluded because the mother was not Latina and three additional dyads that were excluded because they represented families that had a duplicate mother. Specifically, the mothers in these dyads were interviewed twice (i.e., initially when the first daughter/niece was interviewed, and again when the second daughter/niece was interviewed). To eliminate the problem of non-independence of data and the possibility of practice effects, we retained the data from the first interview in which each mother participated, resulting in an analytic sample of 193 dyads.

At W1, adolescents were an average of 16.78 years old (SD = .98), and the majority were in a romantic relationship with the biological father of their baby (67%). The majority of adolescents were attending school (59%). Of the adolescents who were in school or who had graduated by W1, the average level of education attained was 9.63 years (SD = 1.45); 22% had completed 8 years or less, 68% had completed 9-11 years, and 10% had graduated high school. Most adolescents lived with their mothers (87%) in homes that included an average of 4.85 individuals (SD = 2.45). At W1, the majority of adolescents were expecting their first child (i.e., 94%). Mothers were 41.24 years old (SD = 7.11), and the majority were married or cohabiting (65%). On average, mothers had completed 8.79 years of school (SD = 3.25). Specifically, 46% of mothers had completed 8 years of school or less, 26.9% had completed some high school, 16% had a high school degree or equivalent, and 10.9% reported some education beyond high school (e.g., vocational school, Bachelor's degree). With respect to nativity, 62% of adolescents were U.S.-born, and 38% of adolescents were Mexico-born. With respect to mothers, 72% were born in Mexico, 27% were born in the U.S., 1% were born in Guatemala, and .5% were born in El Salvador. On average, mothers had lived in the U.S. for 22.42 years (SD = 14.66).

Procedure

Families for the study were recruited from high schools, health centers, and community agencies in a Southwestern metropolitan area. Adolescents had to be of Mexican-origin, 15 to 18 years old, currently pregnant, not legally married, and have a mother figure who was also willing to participate. All participants older than 18 years of age provided written informed consent to participate. Parental consent and youth assent were obtained for adolescents who were younger than 18 years of age. Adolescents and mothers participated in face-to-face, in-home interviews in which all questions were read aloud by a trained female interviewer. All interviewers completed more than 30 hours of mandatory training that included cultural sensitivity, research ethics, and interviewing techniques. Participants were interviewed separately when the adolescent was in her first trimester of pregnancy (W1), and approximately 12 months later for each subsequent interview (i.e., W2 and W3). A majority of adolescents were interviewed in English (61%), and 69% of mothers were interviewed in Spanish. Each participant received $25 for participation at W1, $30 at W2, and $35 at W3. All procedures were approved by the University's Human Subjects Review Board.

Measures

Nativity

Adolescents reported on demographic characteristics at W1. Nativity (0 = Mexico-born, 1 = U.S.-born) was coded based on self-reported country of birth.

Familism values

Mothers completed the 16-item familism subscale of the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (Knight et al., 2010) at W1 to assess their familism values (e.g., “Parents should teach their children that the family always comes first.”). Responses ranged from (1) Strongly disagree to (5) Strongly agree, and higher scores indicated higher familism values. Cronbach's alpha were .82 (English) and .80 (Spanish).

Mexican involvement

Mothers’ responses to the 17-item Mexican orientation subscale of the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans – II (Cuéllar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995) at W1 were used to assess their involvement in Mexican culture (e.g., “I associate with Mexicans and/or Mexican Americans.”). Responses ranged from (1) Not at all to (5) Extremely often or almost always, and higher scores indicated higher engagement in Mexican-oriented behaviors. Cronbach's alphas were .84 (English) and .78 (Spanish).

Ethnic socialization

Mothers’ responses to the 12-item Familial Ethnic Socialization Measure (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004) at W2 was used to assess mothers’ perceptions of the ethnic socialization they provided to their daughters (e.g., “We talk about how important it is to know about her ethnic/cultural background.”). Responses ranged from (1) Not at all to (5) Very Much, and higher scores indicated higher maternal ethnic socialization. Cronbach's alphas were .94 (English) and .84 (Spanish).

Ethnic-racial identity

Mothers’ responses at W1 and adolescents’ responses at W2 and W3 on the 17-item Ethnic Identity Scale (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004) were used to assess the three dimensions of ERI: exploration (7 items; “I have attended events that have helped me learn more about my ethnicity”); resolution (4 items; “I am clear about what my ethnicity means to me”); and affirmation (6 items; “my feelings about my ethnicity are mostly negative”). Responses ranged from (1) Does not describe me at all to (4) Describes me very well, and negatively worded items were reverse scored so that higher scores indicated higher ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation. For mothers, Cronbach's alpha at W1 ranged from .64 - .88 for English and Spanish versions. For adolescents, Cronbach's alpha at W2 and W3 ranged from .70 - .92 for English and Spanish versions.

Results

Prior to testing the hypothesized model, means, standard deviations and correlations were computed separately based on adolescents’ nativity (see Table 1). In addition, independent samples t-tests were conducted to test for potential mean level differences in study variables between participants with complete data versus those with incomplete data; results indicated that there were no significant differences on any study variable at W1 (i.e., when all participants provided data). The hypothesized model was tested with path analysis via structural equation modeling using Mplus version 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood (Arbuckle, 1996). Three indices were used to examine model fit: the comparative fit index (CFI), the root-mean-square-error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized-root-mean-square residual (SRMR). Model fit was considered to be good if the CFI was ≥ .95, the RMSEA was ≤ .06, and the SRMR ≤ .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Study Variables for Mexico-born (N = 73) and U.S.-born (N = 120) Adolescents.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. W1 A Age | -- | .06 | .12 | .36*** | −.02 | .04 | .06 | .12 | .03 | −.04 | −.20** | .05 | .13 |

| 2. W1 M Familism | −.11 | -- | .28*** | −.05 | −.02 | −.12 | .37*** | −.13 | −.18* | −.10 | .03 | −.04 | .15* |

| 3. W1 M Mexican Involvement | .01 | .24*** | -- | .03 | .07 | −.29*** | .33*** | .11 | −.05 | −.14 | .03 | .16* | −.12 |

| 4. W1 M ERI Exploration | −.12 | .27*** | .23** | -- | .51*** | .12 | .12 | .35*** | .13 | .07 | .02 | .14 | .09 |

| 5. W1 M ERI Resolution | .05 | .23** | .33*** | .49*** | -- | .20** | .27*** | .24*** | .22** | .06 | .08 | .04 | −.20 |

| 6. W1 M ERI Affirmation | .01 | −.11 | −.09 | .06 | .15* | -- | .04 | −.06 | −.04 | −.12 | −.12 | .01 | .14 |

| 7. W2 M Ethnic Socialization | −.13 | .37*** | .19** | .37*** | .25*** | .02 | -- | .13 | .11 | −.03 | .28*** | .38*** | .12 |

| 8. W2 A ERI Exploration | .04 | −.01 | .13 | .02 | .02 | −.13 | .14 | -- | .66*** | .16* | .39*** | .36*** | .09 |

| 9. W2 A ERI Resolution | −.08 | .09 | .04 | .17** | .16* | .02 | .22** | .35*** | -- | .22** | .39*** | .53*** | .08 |

| 10. W2 A ERI Affirmation | .18* | −.06 | −.02 | −.01 | .03 | .20** | −.02 | .07 | .25*** | -- | .10 | .10 | .28*** |

| 11. W3 A ERI Exploration | .05 | −.11 | .12 | −.03 | .06 | −.00 | −.02 | .46*** | .15* | −.05 | -- | .68*** | .40*** |

| 12. W3 A ERI Resolution | .02 | −.10 | .15* | .06 | .19** | .18* | −.02 | .26*** | .11 | .11 | .43 | -- | .50*** |

| 13. W3 A ERI Affirmation | −.02 | −.07 | .11 | .16* | .17** | .42*** | .05 | −.10 | .16* | .55*** | −.11 | .07 | -- |

| Mexico-Born Adolescents | |||||||||||||

| Mean | 16.73 | 4.59 | 4.34 | 2.74 | 3.29 | 3.58 | 3.48 | 3.01 | 3.43 | 3.72 | 3.04 | 3.58 | 3.77 |

| Standard Deviation | .92 | .28 | .46 | .58 | .63 | .61 | .64 | .60 | .69 | .51 | .57 | .69 | .56 |

| U.S.-Born Adolescents | |||||||||||||

| Mean | 16.81 | 4.46 | 3.93 | 2.73 | 3.34 | 3.70 | 3.30 | 2.80 | 3.38 | 3.88 | 2.86 | 3.52 | 3.90 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.01 | .40 | .75 | .69 | .70 | .52 | .77 | .69 | .62 | .32 | .66 | .56 | .36 |

| All Adolescents | |||||||||||||

| Mean | 16.78 | 4.51 | 4.09 | 2.73 | 3.32 | 3.66 | 3.38 | 2.88 | 3.39 | 3.82 | 2.93 | 3.54 | 3.85 |

| Standard Deviation | .98 | .37 | .69 | .66 | .68 | .56 | .73 | .66 | .65 | .40 | .63 | .59 | .44 |

Note. Mexico-born adolescents' correlations are above the diagonal; U.S.-born adolescents' correlations are below the diagonal. W = Wave, A = Adolescent, M = Mother, ERI = Ethnic-Racial Identity.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

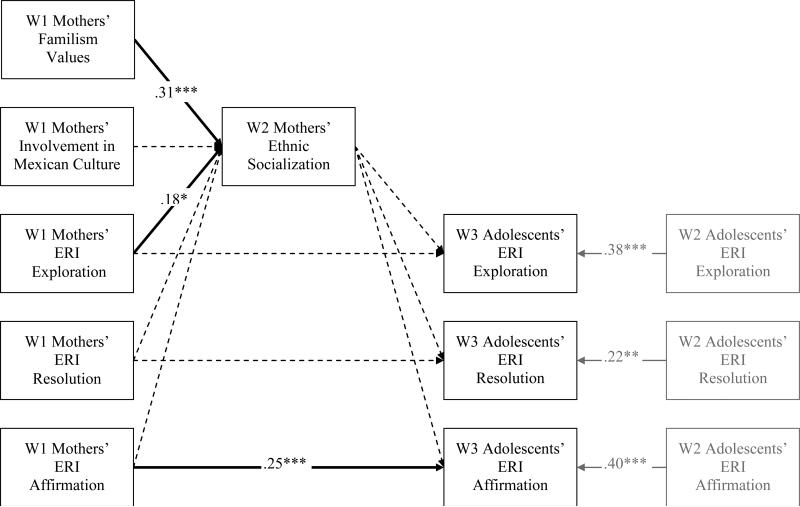

Fit indices for the hypothesized model (Figure 1) indicated a good fit [χ2 (23) = 31.86, p > .05; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .05 (.00 - .08); SRMR = .04]. Mothers’ familism values at W1 (ƅ = .60, SE = .14, p < .001) and ERI exploration at W1 (ƅ = .20, SE = .09, p < .05) were positively associated with maternal ethnic socialization at W2. Contrary to expectations, mothers’ W1 involvement in Mexican culture and W1 ERI resolution were not significantly associated with W2 maternal ethnic socialization (p > .05). Regarding the alternative test of whether components of mothers’ ERI were direct predictors of adolescents’ ERI, the paths were not significant for ERI exploration or resolution, (p > .05); however, mothers’ W1 ERI affirmation was positively associated with increases in adolescents’ ERI affirmation two years later at W3 (ƅ = .19, SE = .05, p < .001), after accounting for ERI affirmation at W2.

Figure 1.

Final model for mothers and adolescents.

Note. W1 = Wave 1, W2 = Wave 2, W3 = Wave 3, ERI = ethnic-racial identity. Black lines indicate hypothesized variables and paths, and grey lines indicate control variables and paths. Solid lines indicate significant paths, and dashed lines indicate non-significant paths. Adolescents’ nativity and age at W1 were included as controls predicting adolescents’ ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation at W3, but are not shown here. In addition, the residuals of all exogenous variables were allowed to be correlated, but are not illustrated above. All path estimates are standardized. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

Discussion

ERI has been associated with positive outcomes among youth (Ghavami et al., 2011; Schwartz et al., 2007). Adolescent mothers are at risk for negative outcomes, such as decreased self-esteem and increased depressive symptoms (e.g., Whitman et al., 2001), and Mexican-origin females in particular are at heightened risk for becoming adolescent mothers (Ventura et al., 2013). Considering this combined high risk for pregnancy and maladjustment, the current study took an intergenerational perspective to consider how mothers’ characteristics and socialization efforts informed adolescent mothers’ ERI.

Guided by bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 2006), we hypothesized that mothers’ cultural characteristics would predict their ethnic socialization efforts; our hypotheses were partially supported. In particular, mothers’ familism values and ERI exploration predicted maternal ethnic socialization; however, mothers’ involvement in Mexican-culture, ERI resolution, and ERI affirmation did not predict maternal ethnic socialization. Our finding regarding the positive association between maternal familism and ethnic socialization a year later is consistent with previous work with early adolescents in a community-based sample (Knight et al., 2011), suggesting that mothers endorsing familism values invest effort into socializing youth about their ethnicity. In addition to familism values, the degree to which mothers had explored their own ethnicity also predicted ethnic socialization. Hughes and colleagues (2006) underscored the dearth of research examining whether parents’ ERI predicted their socialization practices, and suggested that this relation should exist because when ethnicity is salient to parents, they are more likely to be motivated to socialize their children about ethnicity. Our findings support this notion among a sample of parenting adolescents and their mothers. Overall, findings highlight the importance of mothers’ familism values and ERI exploration as important predictors of mothers’ ethnic socialization of adolescent mothers, who are in turn faced with the task of socializing their young children. In future research, an important next step is to examine whether these same cultural characteristics emerge as predictors of maternal ethnic socialization among non-parenting adolescent samples and in different developmental periods.

Consistent with bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), we hypothesized that maternal ethnic socialization would predict ERI among late adolescents in our sample; however our hypotheses were not supported. It is possible that among older adolescents transitioning to adulthood, mothers’ ethnic socialization efforts are only one source of influence among many (e.g., siblings, peers), and to understand how adolescents’ ERI evolves, it is necessary to assess the influence of these multiple sources. Given that previous work has found an association between familial ethnic socialization and adolescents’ ERI (e.g., Supple et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009), it is possible that there may be a cumulative effect, such that multiple family members’ ethnic socialization efforts are necessary to elicit increases in adolescents’ ERI. In the current study, we focused on the ethnic socialization that mothers provided because they have been identified as particularly important to adolescent mothers (Brooks-Gunn & Chase-Lansdale, 1995); however, a key direction for future studies will be to better understand whether the specific source of ethnic socialization matters at different developmental periods and/or whether it is necessary to consider the cumulative impact of different sources of ethnic socialization.

Interestingly, the current findings indicated that mothers’ own ERI affirmation was positively associated with adolescents’ ERI affirmation two years later, controlling for adolescents ERI affirmation one year earlier. Given that ERI affirmation is believed to develop as a function of individuals’ need to maintain a positive sense of self, and the content of socialization messages focused on teaching cultural traditions or history may not necessarily include positive messages about individuals’ ethnic-racial group, it is possible that rather than merely exposing youth to their culture via ethnic socialization efforts, it may be necessary for family members to model positive attitudes about their ethnic group to adolescents in order to inform adolescents’ ERI affirmation. Indeed, social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) posits that individuals can vicariously learn emotions that they internalize for themselves by modeling others in their environment (e.g., parents). Consistent with this notion, mothers may serve as role models of positive regard for their ethnicity (i.e., ERI affirmation), which adolescents learn and internalize for themselves. Modeling may be especially salient to adolescent mothers because of their closeness with and reliance on their mothers as they transition to motherhood. Future work that examines this relation with other samples is warranted, however, as this was the first study to our knowledge to examine this link.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to acknowledge that provide direction for future research. First, with respect to generalizability, the current study focused on Mexican-origin adolescent mothers who were recruited from a large metropolitan region of the southwestern United States, where Mexican-origin individuals represent the majority of the Latino population. Previous work has noted variability in adolescents’ ERI based on the ethnic composition of their social context (e.g., Umaña-Taylor, 2004). It will be important for future research to examine this process with Mexican-origin families in other regions of the United States to determine whether findings generalize to other settings. Second, the current study examined mothers’ cultural characteristics and socialization efforts as predictors of adolescents’ ERI; however, given that bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) posits that there a numerous individuals within various contexts that are informative, future work should test whether additional individuals’ characteristics and socialization efforts (e.g., fathers, teachers, siblings) inform adolescents’ ERI. Furthermore, although a strength of the current study was that we examined processes underlying ERI development among a sample of adolescent mothers who are engaged in the process of identity development and simultaneously faced with the task of socializing their young children, it is possible that the associations of interest were specific to the context of adolescent parenthood because adolescent mothers may be particularly attuned to the transmission of cultural knowledge as they are assuming a similar role as a parent. Future work should examine these associations among samples of adolescent mothers and non-parenting adolescents, to test whether findings vary based on adolescents’ parenting status. Finally, although the current study focused on two process components of ERI (i.e., exploration and resolution) and a content component of ERI (i.e., affirmation), a future direction will be to examine mothers’ and adolescents’ ethnic identity statuses (i.e., foreclosed, diffused, moratorium, and achieved) to determine whether mothers’ ethnic identity status (as informed by the intersection of multiple ERI components) predicts adolescents’ ethnic identity status.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the current study advances the literature on adolescents’ ERI by examining this process among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers as it is informed by their mothers’ cultural characteristics and ethnic socialization efforts. Importantly, the current study provides insight into the intergenerational transmission of cultural values and beliefs via ethnic socialization efforts. Results highlight that familism and ERI exploration are important aspects of mothers’ ethnic socialization efforts with their daughters. In addition, findings underscore the importance of mothers’ own positive feelings toward their ethnicity in informing adolescent daughters’ ERI affirmation over time. Finally, coupled with prior work linking ERI to adolescent mothers’ adjustment (i.e., Sieger & Renk, 2007), our findings suggest that interventions focused on bolstering mothers’ positive feelings toward their culture would be valuable for their adolescent daughters as they transition from pregnancy to parenting.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Department of Health and Human Services (APRPA006011; PI: Umaña-Taylor), the Fahs Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation of the New York Community Trust (PI: Umaña-Taylor), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD061376; PI: Umaña-Taylor) and the Challenged Child Project of the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University.

References

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development. 6th ed. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Chase-Lansdale PL. Adolescent parenthood. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 3. Status and social conditions of parenting. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. pp. 113–149. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras JM, Narang D, Ikhlas M, Teichman J. A conceptual model of the determinants of parenting among Latina adolescent mothers. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the U. S. Praeger; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, Koryzma C, Hua JM, Chance LJ. Ethnic identity, achievement, and psychological adjustment: Examining risk and resilience among youth from immigrant Chinese families in Canada. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16(2):264–273. doi: 10.1037/a0017275. doi: 10.1037/a0017275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A Revision of the Original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–304. doi: 10.1177/07399863950173001. [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest N, Morse E. Ethnic variations in parental ethnic socialization and adolescent ethnic identity: A longitudinal study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2015;21(1):54–64. doi: 10.1037/a0037820. doi: /10.1037/a0037820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton; New York, NY: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami N, Fingerhut A, Peplau LA, Grant SK, Wittig MA. Testing a model of minority identity achievement, identity affirmation, and psychological well-being among ethnic minority and sexual minority individuals. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:79–88. doi: 10.1037/a0022532. doi: 10.1037/a0022532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Hagelskamp C, Way N, Foust MD. The role of mothers and adolescents perceptions of ethnic-racial socialization in shaping ethnic-racial identity among early adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(5):605–626. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9399-7. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettekal I, Jaconis M, Boyd BM. The familial socialization of culturally related values in Mexican American Families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;75:913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Bernal ME, Garza CA, Cota MK, Ocampo KA. Family socialization and the ethnic identity of Mexican-American children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1993;24:99–114. doi: 10.1177/0022022193241007. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén B. Version 6 Mplus user's guide. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Jarvis LH. Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieger K, Renk K. Pregnant and parenting adolescents: A study of ethnic identity, emotional and behavioral functioning, child characteristics, and social support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36(4):567–581. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9182-6. [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, Ghazarian SR, Frabutt JM, Plunkett SW, Sands T. Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77:1427–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00945.x. doi: 10.1111/j.14678624.2006.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Human groups and social categories. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Alfaro EC, Bámaca MY, Guimond A. The central role of familial ethnic socialization in Latino adolescents’ cultural orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:46–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00579.x. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Fine MA. Examining a model of ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin adolescents living in the U.S. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26:36–59. doi: 10.1177/0739986303262143. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Jr., Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, Seaton E. Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development. 2014;85(1):21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA, Jahromi LB, Zeiders KH. An examination of trajectories of ethnic-racial identity and autonomy among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. 2015 doi: 10.1111/cdev.12444. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, Bámaca-Gómez M. Developing the Ethnic Identity Scale using Erikson and social identity perspectives. An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2004;4:9–38. doi: 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura SJ, Hamilton BE, Mathews TJ. Pregnancy and childbirth among females aged 10–19 years — United States, 2007–2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(3):71–76. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6203.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Knight GP, Zeiders KH. Language measurement equivalence of the ethnic identity scale with Mexican American early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2011;31:817–852. doi: 10.1177/0272431610376246. doi: 10.1177/0272431610376246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman TL, Borowski JG, Keogh DA, Weed K. Interwoven lives: Adolescent mothers and their children. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon E. Measuring ethnic identity in the Ethnic Identity Scale and the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure-Revised. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:144–155. doi: 10.1037/a0023361. doi: 10.1037/a0023361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]