Abstract

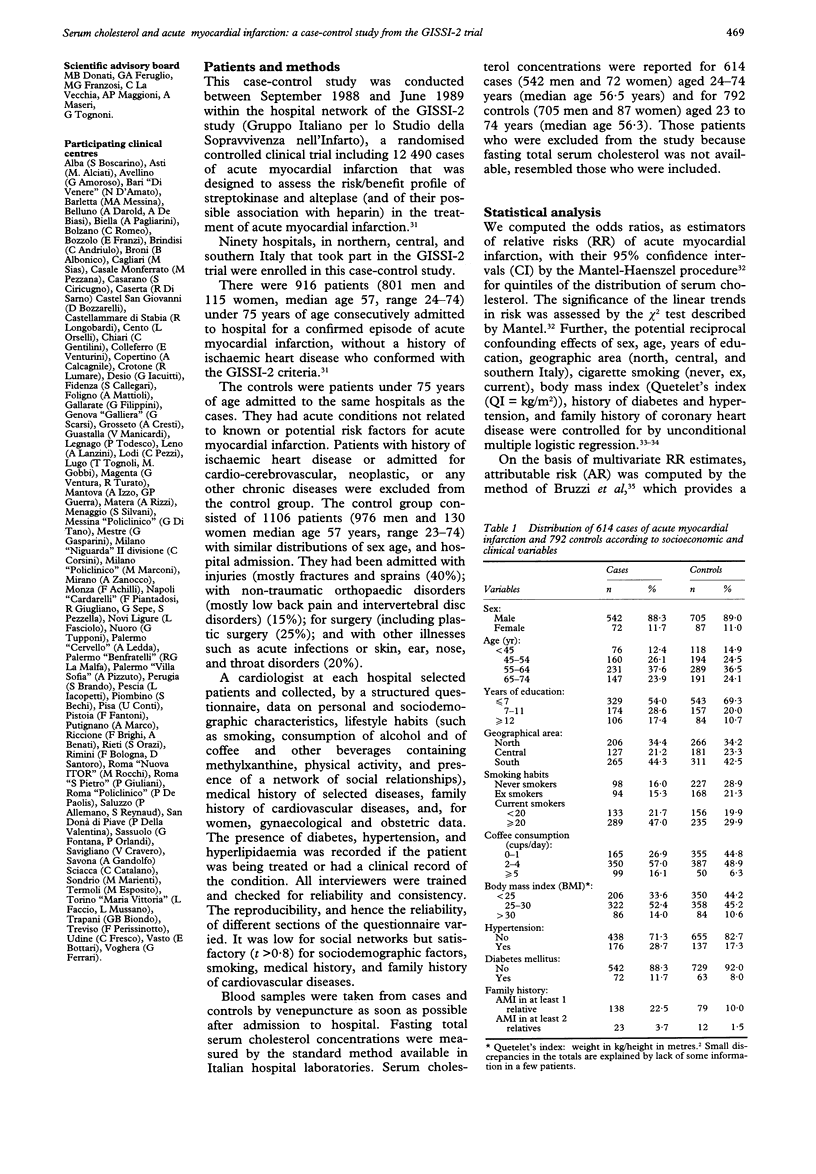

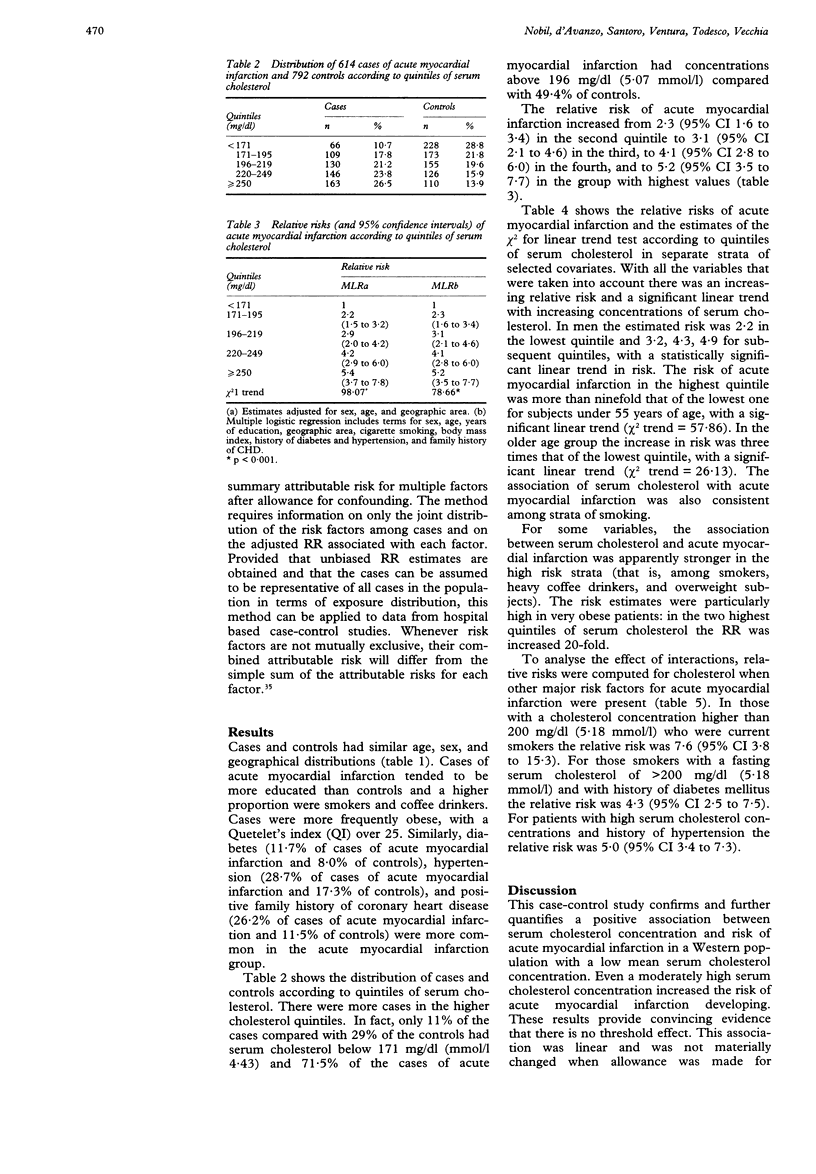

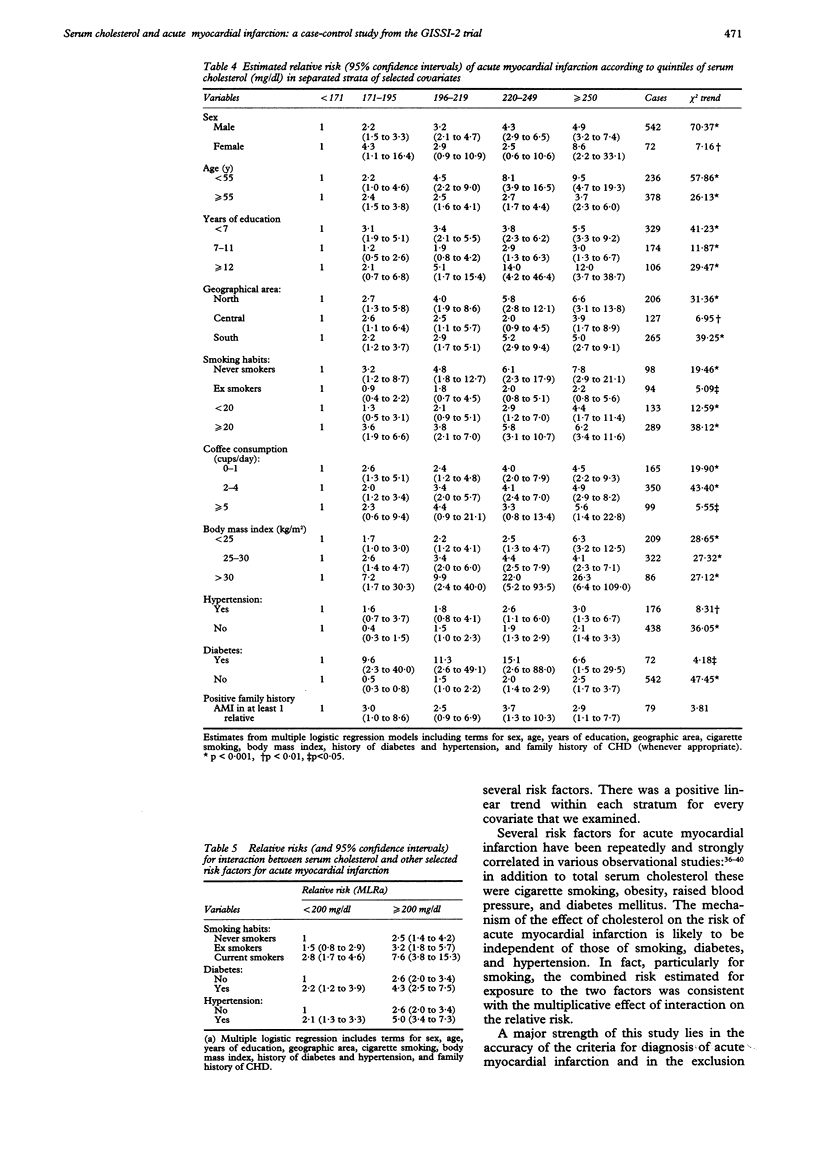

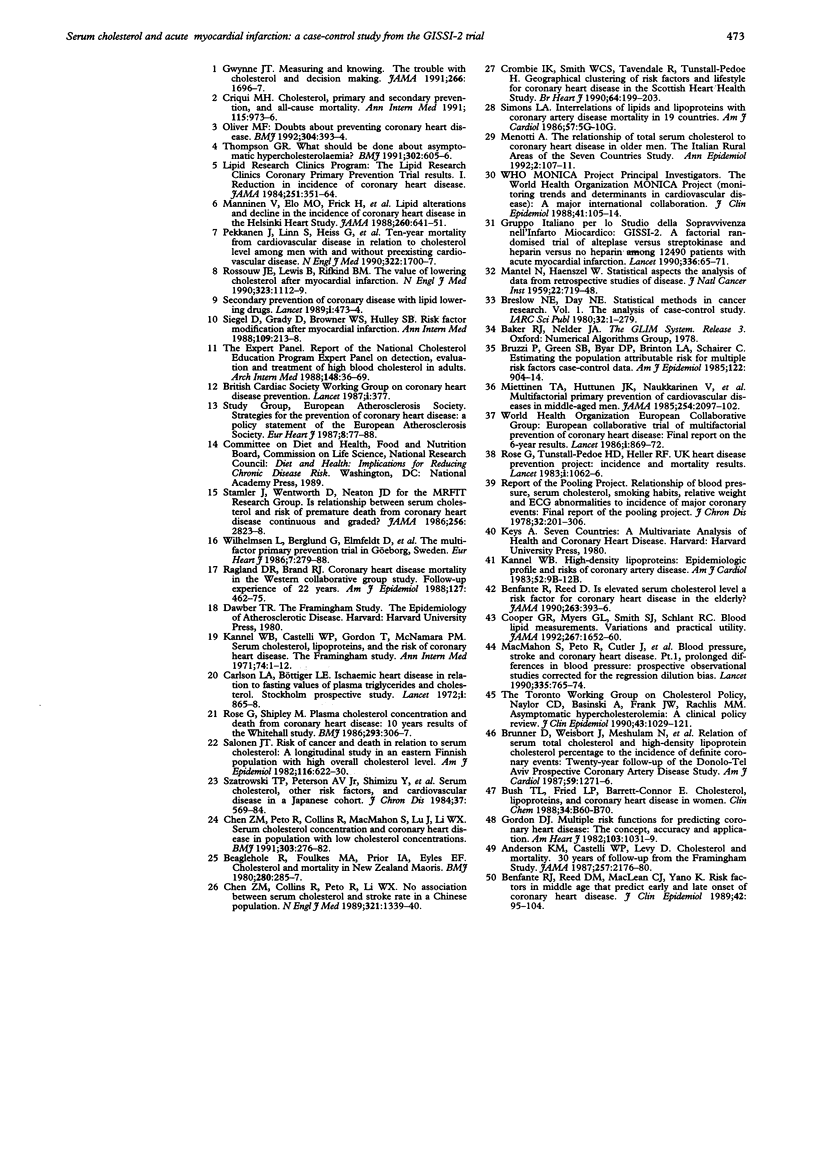

OBJECTIVE--To examine the role of serum cholesterol in acute myocardial infarction in a population of patients with no history of coronary heart disease and to establish the nature of this association, the degree of risk, and the possible interaction between serum cholesterol and other major risk factors for acute myocardial infarction. DESIGN--Case-control study. SETTING--90 hospitals in northern, central, and southern Italy. PATIENTS--916 consecutive cases of newly diagnosed acute myocardial infarction and 1106 hospital controls admitted to hospital with acute conditions not related to known or suspected risk factors for coronary heart disease. DATA COLLECTION--Data were collected with a structured questionnaire and blood samples were taken by venepuncture as soon as possible after admission to hospital from cases and controls. Blood cholesterol concentrations were available for 614 cases and 792 controls. RESULTS--After adjustment by logistic regression for sex, age, education, geographical area, smoking status, body mass index, history of diabetes and hypertension, and family history of coronary heart disease the estimated relative risks of acute myocardial infarction for quintiles of serum cholesterol (from lowest to highest) were 2.3 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.6 to 3.4), 3.1 (95% CI 2.1 to 4.6), 4.1 (95% CI 2.8 to 6.0), and 5.2 (95% CI 3.5 to 7.7). The estimated relative risk across selected covariates increased from the lowest to the highest quintile of serum cholesterol particularly for men, patients under 55 years of age, and smokers. When the possible interaction of known risk factors with serum cholesterol was examined, smoking habits, diabetes, and hypertension had approximately multiplicative effects on relative risk. CONCLUSIONS--This study indicates that serum cholesterol was an independent risk factor for acute myocardial infarction. This association was linear, with no threshold level. Moreover, there was a multiplicative effect between cholesterol and other major risk factors on the relative risk of acute myocardial infarction.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson K. M., Castelli W. P., Levy D. Cholesterol and mortality. 30 years of follow-up from the Framingham study. JAMA. 1987 Apr 24;257(16):2176–2180. doi: 10.1001/jama.257.16.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaglehole R., Foulkes M. A., Prior I. A., Eyles E. F. Cholesterol and mortality in New Zealand Maoris. Br Med J. 1980 Feb 2;280(6210):285–287. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6210.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfante R. J., Reed D. M., MacLean C. J., Yano K. Risk factors in middle age that predict early and late onset of coronary heart disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(2):95–104. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfante R., Reed D. Is elevated serum cholesterol level a risk factor for coronary heart disease in the elderly? JAMA. 1990 Jan 19;263(3):393–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner D., Weisbort J., Meshulam N., Schwartz S., Gross J., Saltz-Rennert H., Altman S., Loebl K. Relation of serum total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol percentage to the incidence of definite coronary events: twenty-year follow-up of the Donolo-Tel Aviv Prospective Coronary Artery Disease Study. Am J Cardiol. 1987 Jun 1;59(15):1271–1276. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90903-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzi P., Green S. B., Byar D. P., Brinton L. A., Schairer C. Estimating the population attributable risk for multiple risk factors using case-control data. Am J Epidemiol. 1985 Nov;122(5):904–914. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush T. L., Fried L. P., Barrett-Connor E. Cholesterol, lipoproteins, and coronary heart disease in women. Clin Chem. 1988;34(8B):B60–B70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson L. A., Böttiger L. E. Ischaemic heart-disease in relation to fasting values of plasma triglycerides and cholesterol. Stockholm prospective study. Lancet. 1972 Apr 22;1(7756):865–868. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)90738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Peto R., Collins R., MacMahon S., Lu J., Li W. Serum cholesterol concentration and coronary heart disease in population with low cholesterol concentrations. BMJ. 1991 Aug 3;303(6797):276–282. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6797.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G. R., Myers G. L., Smith S. J., Schlant R. C. Blood lipid measurements. Variations and practical utility. JAMA. 1992 Mar 25;267(12):1652–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criqui M. H. Cholesterol, primary and secondary prevention, and all-cause mortality. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Dec 15;115(12):973–976. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-12-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombie I. K., Smith W. C., Tavendale R., Tunstall-Pedoe H. Geographical clustering of risk factors and lifestyle for coronary heart disease in the Scottish Heart Health Study. Br Heart J. 1990 Sep;64(3):199–203. doi: 10.1136/hrt.64.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon T., Kannel W. B. Multiple risk functions for predicting coronary heart disease: the concept, accuracy, and application. Am Heart J. 1982 Jun;103(6):1031–1039. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90567-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwynne J. T. Measuring and knowing. The trouble with cholesterol and decision making. JAMA. 1991 Sep 25;266(12):1696–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.266.12.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel W. B., Castelli W. P., Gordon T., McNamara P. M. Serum cholesterol, lipoproteins, and the risk of coronary heart disease. The Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1971 Jan;74(1):1–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-74-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANTEL N., HAENSZEL W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959 Apr;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMahon S., Peto R., Cutler J., Collins R., Sorlie P., Neaton J., Abbott R., Godwin J., Dyer A., Stamler J. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990 Mar 31;335(8692):765–774. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manninen V., Elo M. O., Frick M. H., Haapa K., Heinonen O. P., Heinsalmi P., Helo P., Huttunen J. K., Kaitaniemi P., Koskinen P. Lipid alterations and decline in the incidence of coronary heart disease in the Helsinki Heart Study. JAMA. 1988 Aug 5;260(5):641–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti A. The relationship of total serum cholesterol to coronary heart disease in older men. The Italian rural areas of the Seven Countries Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1992 Jan-Mar;2(1-2):107–111. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(92)90044-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen T. A., Huttunen J. K., Naukkarinen V., Strandberg T., Mattila S., Kumlin T., Sarna S. Multifactorial primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in middle-aged men. Risk factor changes, incidence, and mortality. JAMA. 1985 Oct 18;254(15):2097–2102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M. F. Doubts about preventing coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1992 Feb 15;304(6824):393–394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6824.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekkanen J., Linn S., Heiss G., Suchindran C. M., Leon A., Rifkind B. M., Tyroler H. A. Ten-year mortality from cardiovascular disease in relation to cholesterol level among men with and without preexisting cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1990 Jun 14;322(24):1700–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006143222403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragland D. R., Brand R. J. Coronary heart disease mortality in the Western Collaborative Group Study. Follow-up experience of 22 years. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Mar;127(3):462–475. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G., Shipley M. Plasma cholesterol concentration and death from coronary heart disease: 10 year results of the Whitehall study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986 Aug 2;293(6542):306–307. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6542.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G., Tunstall-Pedoe H. D., Heller R. F. UK heart disease prevention project: incidence and mortality results. Lancet. 1983 May 14;1(8333):1062–1066. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91907-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw J. E., Lewis B., Rifkind B. M. The value of lowering cholesterol after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1990 Oct 18;323(16):1112–1119. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010183231606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen J. T. Risk of cancer and death in relation to serum cholesterol. A longitudinal study in an eastern Finnish population with high overall cholesterol level. Am J Epidemiol. 1982 Oct;116(4):622–630. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serum cholesterol levels and stroke mortality. N Engl J Med. 1989 Nov 9;321(19):1339–1341. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D., Grady D., Browner W. S., Hulley S. B. Risk factor modification after myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1988 Aug 1;109(3):213–218. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-3-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamler J., Wentworth D., Neaton J. D. Is relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease continuous and graded? Findings in 356,222 primary screenees of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT). JAMA. 1986 Nov 28;256(20):2823–2828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatrowski T. P., Peterson A. V., Jr, Shimizu Y., Prentice R. L., Mason M. W., Fukunaga Y., Kato H. Serum cholesterol, other risk factors, and cardiovascular disease in a Japanese cohort. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37(7):569–584. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson G. R. What should be done about asymptomatic hypercholesterolaemia? BMJ. 1991 Mar 16;302(6777):605–606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6777.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen L., Berglund G., Elmfeldt D., Tibblin G., Wedel H., Pennert K., Vedin A., Wilhelmsson C., Werkö L. The multifactor primary prevention trial in Göteborg, Sweden. Eur Heart J. 1986 Apr;7(4):279–288. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]