Abstract

Acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis (AOSC) due to biliary lithiasis is a life-threatening condition that requires urgent biliary decompression. Although endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with stent placement is the current gold standard for biliary decompression, it can sometimes be difficult because of failed biliary cannulation. In this retrospective case series, we describe three cases of successful biliary drainage with recovery from septic shock after urgent endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS) was performed for AOSC due to biliary lithiasis. In all three cases, technical success in inserting the stents was achieved and the patients completely recovered from AOSC with sepsis in a few days after EUS-CDS. There were no procedure-related complications. When initial ERCP fails, EUS-CDS can be an effective life-saving endoscopic biliary decompression procedure that shortens the procedure time and prevents post-ERCP pancreatitis, particularly in patients with AOSC-induced sepsis.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage, Choledochoduodenostomy, Acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis, Sepsis, Life-saving endoscopy

Core tip: We present 3 cases of urgent endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS) performed for acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis (AOSC)-induced sepsis due to benign lesions. In all three cases, technical success in inserting the stents was achieved and the patients completely recovered from AOSC with sepsis in a few days after EUS-CDS. Although endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with transpapillary stent placement is the current gold standard for biliary decompression, this technique is not always successful. In this situation, EUS-CDS can be an effective life-saving biliary decompression procedure that can shorten the procedure time and prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis, particularly in patients with AOSC-induced sepsis.

INTRODUCTION

Acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis (AOSC) due to biliary lithiasis is a life-threatening condition that requires urgent biliary decompression. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with transpapillary stent placement is the current gold standard for biliary decompression. Endoscopic transpapillary stent placement can sometimes be difficult because of failed biliary cannulation. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) has been increasingly used as an alternative in patients with malignant biliary obstruction after failed initial ERCP[1-4]. However, this technique is not usually indicated for benign biliary lesions. Here we describe three cases of successful biliary drainage with full recovery from septic shock after urgent EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS) was performed for AOSC-induced sepsis. All procedures were carried out by a single experienced endoscopist (M.K.) at a tertiary-care referral center. All EUS procedures were performed using a therapeutic linear echoendoscope (GF-UCT260; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) with carbon dioxide insufflation. The collection of clinical data for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kinki University Faculty of Medicine and all study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

CASE REPORT

Patient 1

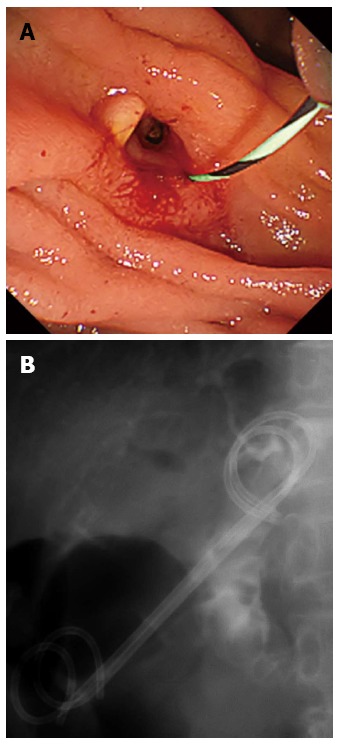

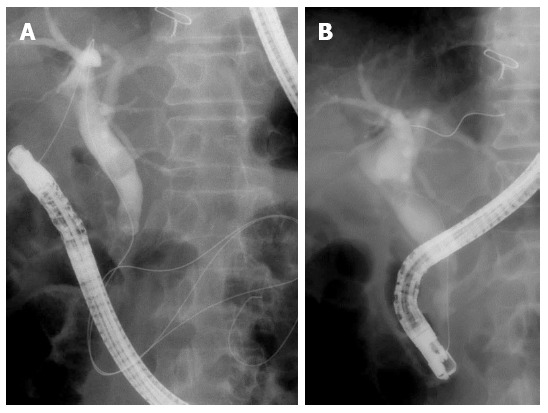

An 83-year-old woman with septic shock due to common bile duct (CBD) stones was referred to our hospital. Urgent ERCP had been performed at a neighboring general hospital; however, biliary cannulation was unsuccessful even with needle-knife precut papillotomy. Intravenous norepinephrine had been administered to maintain systolic blood pressure. Her vital signs were as follows: Glasgow coma scale (GCS) conscious level of E3V4M3, blood pressure of 75/55 mmHg, heart rate of 108 beats/min, and body temperature of 39.2 °C. Laboratory tests showed an elevated inflammatory reaction [white blood cell count (WBC), 38300/μL; serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level, 17.7 mg/dL; and serum procalcitonin (PCT), 64.3 ng/mL]. Elevated levels of serum liver function parameters and bilirubin were also noted [aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 123 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 169 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 220 IU/L; and total bilirubin, 5.2 mg/dL]. Computed tomography (CT) revealed large piled-up CBD stones and dilatation of CBD. Because the intrahepatic bile ducts were not dilated, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) seemed to be difficult. Thus, we decided to perform EUS-CDS. The procedure was performed without intubation after administration of a small amount of intravenous midazolam. The depth of the patient’s sedation was titrated by continuous monitoring with a bispectral index monitor and a pulse oximetry. On EUS, the dilated CBD was accessed from the duodenum bulb. First, the CBD was punctured using a 19-gauge needle (Sono Tip Pro Control; Medi-Globe, Rosenheim, Germany) under echoendoscopic guidance (Figure 1A). Bile was aspirated, and then contrast medium was injected. A 0.025-inch guidewire (VisiGlide 2; Olympus Medical Systems) was placed into the CBD. The fistula was dilated using a 4-mm balloon catheter (ZARA; Century Medical, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 1B), and a covered metallic stent (8-mm wide, 80-mm long; WallFlex partially covered stent; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States) and a 6-Fr endoscopic nasobiliary drainage catheter were inserted (Figure 1C). The duration for the procedure was 21 min. The patient completely recovered in a few days and was discharged 14 d after admission. One month later, we removed the metallic stents and inserted two 7-Fr plastic stents via the EUS-CDS fistula to keep it patent (Figure 2). When we suggested options for performing rendezvous technique via the CDS fistula or surgery to extract the CBD stones, the patient and her family did not choose to undergo these procedures because she did not have any new symptoms. Therefore, we decided to exchange stents semiannually. During 8 mo of follow-up, the patient was free of any symptoms and we exchanged the stents endoscopically 6 mo after the initial procedure.

Figure 1.

Images of patient 1 who underwent urgent endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy. A: EUS-guided common bile duct (CBD) puncture; B: EUS-guided cholangiography showed large piled-up CBD stones. Fistula track was dilated using a 4-mm balloon catheter; C: A covered metallic stent and an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage catheter were successfully placed via the duodenum bulb. EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound.

Figure 2.

Images of biliary cannulation and plastic stent placement via an endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy fistula. A: A matured fistula was created where the removed metallic stent was placed. The common bile duct (CBD) was cannulated via the EUS-CDS fistula using an ERCP catheter and a guidewire was inserted; B: Two 7-Fr double pigtail plastic stents were placed into the CBD via the EUS-CDS fistula. EUS-CDS: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Patient 2

An 85-year-old woman with septic shock due to CBD stones was referred to our hospital. Urgent ERCP had been attempted at a neighboring general hospital. Biliary cannulation had failed because of the presence of juxtapapillary diverticulum. The patient’s vital signs were as follows: GCS conscious level of E2V2M3, blood pressure of 193/92 mmHg, heart rate of 120 beats/min, and body temperature of 39.8 °C. Laboratory tests showed an elevated inflammatory reaction (WBC, 93600/μL; serum CRP, 11.6 mg/dL; and serum PCT, 30.1 ng/mL). Elevated levels of serum liver function parameters and bilirubin were also remarkable (AST, 567 IU/L; ALT, 372 IU/L; ALP, 1312 IU/L; and total bilirubin, 5.0 mg/dL). CT revealed large multiple CBD stones, and the CBD was dilated approximately 18 mm. Because urgent biliary drainage was required to treat septic shock, we performed EUS-CDS. The intrahepatic bile ducts were slightly dilated on EUS; therefore, the dilated CBD was punctured from the duodenum bulb using a 19-gauge needle. A 0.025-inch guidewire was placed into the CBD. Then, the fistula was dilated using a 7-Fr dilation catheter, and a covered metallic stent (8-mm-wide and 60-mm-long; WallFlex) was placed. The duration for the procedure was 18 min. The patient recovered completely in a few days and was discharged 12 d after admission. One month later, we removed the metallic stents and inserted two 7-Fr plastic stents via the EUS-CDS fistula. We suggested options for performing rendezvous technique or surgery in the same manner as described in case 1, she did not wish for these invasive procedures. Therefore, we decided to exchange stents semiannually. During 4 mo of follow-up, the patient was free of any symptoms.

Patient 3

An 80-year-old man with severe cholangitis due to CBD stones was referred to our hospital. His vital signs were as follows: GCS conscious level of E3V4M5, blood pressure of 170/77 mmHg, heart rate of 102 beats/min, and body temperature of 38.6 °C. Laboratory tests showed an elevated inflammatory reaction (WBC, 13200/μL and serum CRP, 6.7 mg/dL). Elevated liver function parameters and bilirubin level were also noted (AST, 306 IU/L; ALT, 324 IU/L; ALP, 1510 IU/L; and total bilirubin, 1.8 mg/dL). His platelet count decreased to 96000/μL. He also had disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (defined as an acute DIC score ≥ 4) complicated by acute cholangitis induced-sepsis. CT revealed two CBD stones with a diameter of 12 mm. Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin was administered to treat DIC. Then, urgent ERCP was attempted. Deep biliary cannulation failed even after using a double-guidewire technique. To treat the sepsis, we performed EUS-CDS in the same session. The dilated CBD was punctured from the duodenum bulb using a 19-gauge needle. A 0.025-inch guide wire was placed into the CBD. Then, the fistula was dilated using a 7-Fr dilation catheter, and a 7-Fr straight plastic stent (70-mm-long; Flexima, Boston Scientific) was placed. The duration for ERCP and EUS-CDS procedures was 43 min and 18 min, respectively. The patient recovered fully in a few days. One month later, we removed the plastic stent, and because the guidewire was successfully advanced through the papilla, we performed a rendezvous technique via the EUS-CDS fistula (Figure 3). After achieving transpapillary biliary cannulation, endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed, and two stones were removed using a retrieval balloon. Follow-up MRCP obtained 6 mo later showed no recurrence of bile duct stones.

Figure 3.

Images of a rendezvous technique via the endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy fistula. A: The common bile duct was cannulated via the EUS-CDS fistula and a guidewire was advanced into the duodenum through the papilla; B: The guidewire was caught in the duodenum and transpapillary biliary cannulation was succeeded.

DISCUSSION

Acute cholangitis is a systemic infectious disease characterized by acute inflammation and biliary tract infection. AOSC is a severe form of cholangitis in which pus collects in the biliary tract. According to the newly published Updated Tokyo Guidelines for management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis (TG13), biliary tract drainage should be performed as soon as possible in patients with AOSC[5]; otherwise, translocation of bacteria into the bloodstream causes sepsis, which is a fatal complication of acute cholangitis that induces severe organ damage and high mortality. Endoscopic retrograde biliary stenting is the current gold standard treatment for acute cholangitis due to biliary lithiasis; however, it may be impossible in patients with selective cannulation failure of the major papilla. In this situation, PTBD is an alternative method, but is sometimes difficult when the intrahepatic bile ducts are not dilated.

Since being first reported in 2001 by Giovannini et al[1] EUS-BD has been increasingly performed as an alternative in patients with malignant biliary obstruction for failed ERCP[1-4]. Various techniques of EUS-BD have been described, including EUS-CDS, EUS-guided rendezvous (EUS-RV), and EUS-guided antegrade stent placement. Among these, because EUS-RV preserves the anatomical integrity of the biliary tree and avoids permanent fistula creation, it can be a first-line EUS-BD technique in patients with an endoscopically accessible papilla[6]. There still remain technically challenging aspects, including difficulty in negotiating the guidewire across the obstruction and papilla[6]. Furthermore, EUS-RV needs scope exchange and may require a long procedure time[7]. Püspök et al[8] indicated that, compared with EUS-RV, EUS-CDS has several advantages. One is that the fistulous tract created by a puncture of the bile duct is immediately sealed within the same session, which minimizes the risk of significant bile leakage. However, the main indication for EUS-CDS was malignant distal biliary obstruction due to pancreato-biliary malignancies. A recent review, which included 36 studies of EUS-CDS, found that EUS-CDS for benign biliary stricture was performed in only two cases[9]. For acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis, EUS-CDS was performed in only one case[10]. Therefore, the indication for benign biliary disease has not been established. In our series, we experienced three cases of successful urgent EUS-CDS for AOSC due to choledocholithiasis, and there were no procedure-related complications in any of the cases. We suggest that patients with AOSC due to biliary lithiasis after failed ERCP could be preferred candidates for EUS-CDS because endoscopic procedure of long duration may lead to causing increase in morbidity and mortality especially in elderly patients with AOSC-induced sepsis.

The drainage of the CBD can be achieved by two different types of stents, metal and plastic. In cases 1 and 2, covered metallic stents were deployed and in case 3, plastic stent was deployed. According to a recent systematic analysis, the post-procedure adverse events were lower in the metallic stents although there were no differences in technical and functional success rates between metallic and plastic stents[11]. In case 3, the patient had increased risk of bleeding due to DIC. Concerning this risk, we avoided to insert a metallic stent for it needs fistula dilation using a balloon catheter. We placed a nasobiliary tube through the metallic stent in case 1 because the previous report recommended the use of a nasobiliary drain for 48 h to decrease the pressure in the punctured bile duct[12]. In case 2, we attempted to place the nasobiliary tube but the guidewire slipped and failed to place it.

In one case, we extracted CBD stones using a RV technique, and in the other two cases, the patients and their families didn’t wish for RV technique or surgery due to advanced age, we routinely exchanged the plastic stents to keep the fistula patent. Endoscopic transpapillary biliary stenting remains an effective alternative for patients with stones difficult to manage by conventional endoscopic methods and those who are unfit for surgery or have high surgical risks[13,14]. There is no standardized time period for routine stent replacement of endoscopic transpapillary biliary stenting. Stent patency rates declined rapidly from 94% at 6 mo to 79% at 12 mo and 58% at 24 mo[15]. Therefore we decided to exchange stents semiannually in case 1 and 2.

Recent large studies have identified repeated cannulation attempts with standard approach as a risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP)[16]. It is important to change the procedure early to achieve safe and effective bile cannulation with a shorter procedure time. For prevention of PEP, EUS-CDS is a more advantageous procedure because the pancreas is untouched.

Although endoscopic retrograde biliary stenting has been well-established technique for providing biliary decompression in patients with bile duct obstruction, we believe that EUS-CDS will be a suited salvage to patients whom ERCP cannot be performed. There are still some problems to be solved. One is that bile leak is a concern during EUS-guided biliary interventions and previous studies have demonstrated that biliary leakage into the peritoneal space is the most common complications of EUS-BD[3,4,17]. Therefore, the development of new comfortable stenting device that facilitates simultaneous puncture/dilation is needed. If it becomes available, EUD-CDS will become easier and safer in the future.

The limitations of this study were the small number of patients, lack of a control group, and the inclusion of only a single operator at a single tertiary-care referral center.

In conclusion, with regards to a failed standard ERCP, EUS-CDS can be an effective life-saving biliary decompression procedure that can shorten the procedure time and prevent PEP, particularly in patients with AOSC-induced sepsis. Further long-term studies with a larger cohort are needed to prove the efficacy and safety of this technique.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

Three elderly patients (1 male, 2 female) presented with sepsis from acute cholangitis.

Clinical diagnosis

Acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis (AOSC) with sepsis due to biliary lithiasis.

Differential diagnosis

Tumors (pancreatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, ampullary cancer or metastasis) or benign bile duct stricture/stenosis.

Laboratory diagnosis

The laboratory findings showed an elevated inflammatory reaction and elevated levels of serum liver function parameters and bilirubin.

Imaging diagnosis

Computed tomography revealed common bile duct (CBD) stones and dilatation of CBD.

Pathological diagnosis

Pathological examination was not performed in any of the patients.

Treatment

Urgent endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS) via the duodenum bulb.

Related reports

EUS-CDS is commonly performed in patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction due to pancreato-biliary malignancies. In contrast, there are few reports performing this technique for benign biliary lesions.

Term explanation

EUS-CDS is a novel alternative technique for biliary drainage in patients for whom endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has failed and who prefer internal rather than percutaneous biliary drainage or surgical bypass procedures.

Experiences and lessons

Urgent EUS-CDS for AOSC-induced sepsis due to biliary lithiasis can be an effective life-saving endoscopic biliary decompression procedure that can shorten the procedure time and prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Peer-review

This case report is well written and the topic is interesting. This report describes the successful use of EUS-CDS in three patients with AOSC-induced sepsis due to biliary lithiasis.

Footnotes

Supported by The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and the Japanese Foundation for the Research and Promotion of Endoscopy, No. 22590764 and 25461035.

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kinki University Faculty of Medicine.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare no conflicts-of-interest related to this article.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: December 12, 2015

First decision: December 30, 2015

Article in press: January 30, 2016

P- Reviewer: Amornyotin S, Giannopoulos GA, Kayaalp C, Muguruma N, Skok P, Yan SL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Giovannini M, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, Bories E, Lelong B, Delpero JR. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided bilioduodenal anastomosis: a new technique for biliary drainage. Endoscopy. 2001;33:898–900. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artifon EL, Aparicio D, Paione JB, Lo SK, Bordini A, Rabello C, Otoch JP, Gupta K. Biliary drainage in patients with unresectable, malignant obstruction where ERCP fails: endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy versus percutaneous drainage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:768–774. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31825f264c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahaleh M, Hernandez AJ, Tokar J, Adams RB, Shami VM, Yeaton P. Interventional EUS-guided cholangiography: evaluation of a technique in evolution. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park do H, Jang JW, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. EUS-guided biliary drainage with transluminal stenting after failed ERCP: predictors of adverse events and long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1276–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miura F, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Pitt HA, Gouma DJ, Garden OJ, Büchler MW, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, et al. TG13 flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:47–54. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0563-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwashita T, Yasuda I, Mukai T, Iwata K, Ando N, Doi S, Nakashima M, Uemura S, Mabuchi M, Shimizu M. EUS-guided rendezvous for difficult biliary cannulation using a standardized algorithm: a multicenter prospective pilot study (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YS, Gupta K, Mallery S, Li R, Kinney T, Freeman ML. Endoscopic ultrasound rendezvous for bile duct access using a transduodenal approach: cumulative experience at a single center. A case series. Endoscopy. 2010;42:496–502. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Püspök A, Lomoschitz F, Dejaco C, Hejna M, Sautner T, Gangl A. Endoscopic ultrasound guided therapy of benign and malignant biliary obstruction: a case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1743–1747. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogura T, Higuchi K. Technical tips of endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:820–828. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i3.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horaguchi J, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Ito K, Obana T, Takasawa O, Koshita S, Kanno Y. Endosonography-guided biliary drainage in cases with difficult transpapillary endoscopic biliary drainage. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:239–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang K, Zhu J, Xing L, Wang Y, Jin Z, Li Z. Assessment of efficacy and safety of EUS-guided biliary drainage: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giovannini M, Pesenti Ch, Bories E, Caillol F. Interventional EUS: difficult pancreaticobiliary access. Endoscopy. 2006;38 Suppl 1:S93–S95. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-946665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain SK, Stein R, Bhuva M, Goldberg MJ. Pigtail stents: an alternative in the treatment of difficult bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:490–493. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J, Peng JY, Chen W. Endoscopic biliary stenting for irretrievable common bile duct stones: Indications, advantages, disadvantages, and follow-up results. Surgeon. 2012;10:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li KW, Zhang XW, Ding J, Chen T, Wang J, Shi WJ. A prospective study of the efficacy of endoscopic biliary stenting on common bile duct stones. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:328–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng CL, Sherman S, Watkins JL, Barnett J, Freeman M, Geenen J, Ryan M, Parker H, Frakes JT, Fogel EL, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:139–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poincloux L, Rouquette O, Buc E, Privat J, Pezet D, Dapoigny M, Bommelaer G, Abergel A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage after failed ERCP: cumulative experience of 101 procedures at a single center. Endoscopy. 2015;47:794–801. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]