Abstract

Recognition of RNA by high-affinity binding small molecules is crucial for expanding existing approaches in RNA recognition, and for the development of novel RNA binding drugs. A novel neomycin dimer benzimidazole conjugate 5 (DPA 83) was synthesized by conjugating a neomycin-dimer with benzimidazole alkyne using click chemistry to target multiple binding sites on HIV TAR RNA. Ligand 5 significantly enhances the thermal stability of HIV TAR RNA and interacts stoichiometrically with HIV TAR RNA with a low nanomolar affinity. 5 displayed enhanced binding than its individual building blocks including neomycin dimer azide and benzimidazole alkyne. In essence, a high affinity multivalent ligand was designed and synthesized to target HIV TAR RNA.

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency virus) is a global epidemic which has affected ~37 million people across the world since its discovery.1 Notably, the HIV pandemic severely affected the under-developed countries with nearly 70% of HIV infected population residing in Sub-Saharan Africa.1 A key step which strongly proliferates HIV viral infection takes place in a post-fusion state of HIV virus. In virus infected cells the DNA transcription process is strongly triggered by the formation of complex between the viral TAT protein (88 amino acid residue) and its cognate HIV TAR (Transactivation response region) RNA. HIV TAR RNA is a highly conserved 59-base stem-loop structure located at the 5’-end of all nascent viral transcripts.2,3 Therefore, the TAR RNA-TAT complex is an attractive target for therapeutic intervention.

A myriad of small molecules have been discovered as antagonist of TAR RNA-TAT assembly including intercalators,4 (ethidium bromide5 and proflavine), DNA minor groove binders6 (Hoechst 33258, and DAPI), phenothiazine,7 argininamide,8 peptides,9 peptidomimetics,10 cyclic mimic of TAT-peptide,11, 12 and aminoglycosides13. Majority of these binders display low to medium range micromolar affinity. To enhance selectivity and specificity towards HIV TAR RNA, a dual recognition approach has been employed by our lab and others.11, 14 Varani’s group utilized acyclic peptide which simultaneously targeted the bulge and apical loop region of HIV TAR RNA.11

In the similar vein, we have achieved dual and multi recognition using neomycin-based conjugates.15–24

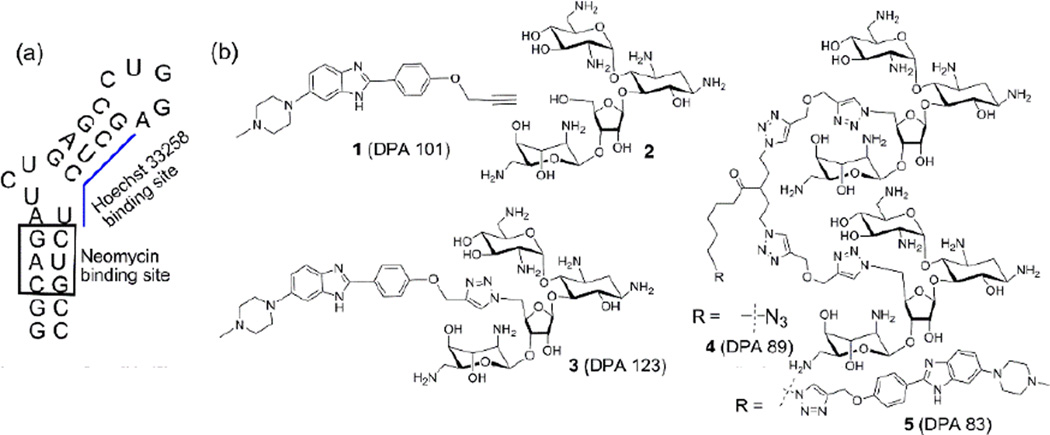

Neomycin, a broad spectrum aminoglycoside, has been known to target both RNA and DNA structures in a nucleic acid shape dependent binding pattern with varying affinities.25–34. Binding of neomycin to TAR-RNA, displayed low micromolar affinity using both NMR titration and gel electrophoresis.13 Mass spectrometry35 and ribonuclease protection experiments36 suggested that neomycin resides in the binding pocket formed by the minor groove of the lower stem of HIV TAR RNA and eventually impedes the essential TAT-TAR RNA interactions during complex formation. Further mass spectrometry binding site experiments and gel shift assays have revealed the existence of three neomycin binding sites in HIV TAR RNA.35 Interestingly, Hoechst 33258, a bisbenzimidazole, has been shown to bind with HIV TAR RNA by intercalating in the upper stem region.6 Therefore, design of a scaffold where both neomycin and benzimidazole are constituent units could potentially target multiple binding sites on HIV TAR RNA.

We have recently reported that dimeric neomycin conjugates display significantly enhanced binding to TAR-RNA in comparison to neomycin.37, 38 We have also shown that a neomycin-benzimidazole conjugate (3, DPA 123) synthesized via conjugation of neomycin to a Hoechst 33258 derived monobenzimidazole (1, DPA 101) resulted in enhanced binding than its individual components (1 and 2).14

The success of this dual binding motif relies on the synergistic binding of the two binding units at independent sites on TAR RNA. Here we extrapolate the idea of dual recognition using a dimeric neomycin-benzimidazole conjugate (5, DPA 83) (Fig. 1 and Scheme 1). DPA 83 (5) combines a click linked neomycin dimer and a benzimidazole alkyne. This ligand 5 (DPA 83), in principle, has been designed to recognize TAR RNA using monomers that binditin a non-competitive (independent binding site) manner. We surmise that the linker joining the dimeric neomycin and benzimidazole units will allow flexibility to the two binding units to reach their desired binding sites since both neomycin and benzimidazole binding sites on TAR-RNA are independent from each other. A surrogate RNA sequence, 29-mer HIV TAR RNA which contains functionally relevant region of wild-type 59-mer is used to investigate the binding interaction using biophysical assays.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the molecules used in the study. (a) Functionally relevant sequence of TAR-RNA used in the study. Boxed and blue underlined regions depict neomycin and Hoechst 33258 binding sites respectively. (b) Chemical structures of the ligands used in this study.

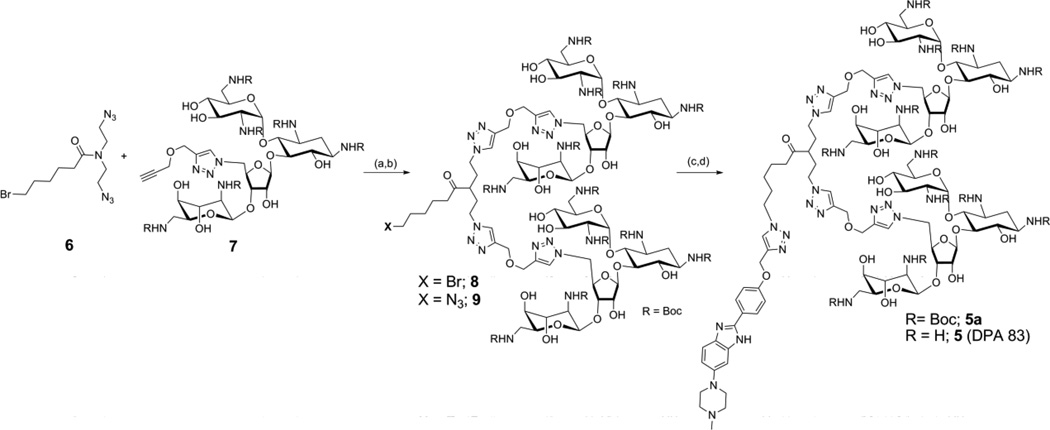

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compound 5. Reagent and conditions: (a) CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, ethanol, water, r.t., 20 h, 80%. (b) NaN3, DMF/H2O (10/1, (v,v)), 90 °C, 15 h, 95%. (c) CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, ethanol/water, 1 (DPA 101), r.t., 20 h, 73.6%. (d) 4 M HCl/dioxane, r.t., 10 min, 73%.

Synthesis of neomycin dimer benzimidazole conjugate, 5 (DPA 83) using click chemistry

N,N-bis(2-azidoethyl)-6-bromohexanamide (6) was synthesized in two steps from commercially available bis(chloro ethyl) amine hydrochloride (See supporting information, Scheme S1).39 A bis-click conjugation of compound 6 with a Bocprotected neomycin alkyne derivative (7, See supporting information Scheme S2 for synthesis details) yielded a bromo-ended neomycin dimer (8) which was converted to its corresponding azide (9) by reacting with sodium azide. Successive click reaction40 between a benzimidazole alkyne (1) and compound 9 yielded Boc protected DPA 83 (5a) which upon acid treatment (4 M HCl) resulted into 5 (DPA 83) as a hydrochloride salt (Scheme 1 and supporting information for complete synthetic detail and characterization).

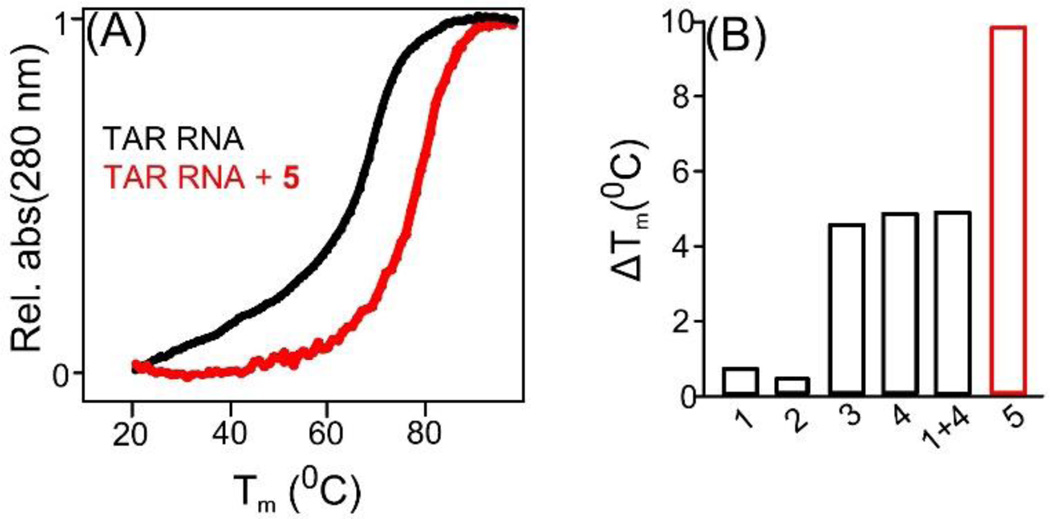

5 significantly enhances the thermal stabilization of HIV TAR RNA

UV thermal denaturation studies were conducted to monitor the effect of ligands on HIV TAR-RNA (Fig. 2) The melting temperature (Tm) of HIV TAR RNA (1 µM/strand) was 68.9 °C in the presence of 100 mM KCl. The thermal stabilization of HIV TAR RNA was insignificant (~1°C) in the presence of ligands 1 and 2 which served as controls.[11,12] A neomycin dimer (4, see supporting information scheme S3 for synthesis details), which is a constituent unit of compound 5, enhanced the thermal stabilization of HIV TAR RNA by ~5°C. Ligand 3 afforded a thermal stabilization comparable to 4. Another control experiment using a 1:1 mixture of 3 and 4 enhanced the melting temperature by ~5 °C.

Figure 2.

Effect of indicated ligands on the thermal stability of HIV TAR RNA. (A) Representative UV thermal denaturation profile of HIV TAR RNA in the absence and presence of 5 at equimolar ratio. (B) Comparison of the thermal stability of HIV TAR RNA in the presence of indicated ligands. Buffer conditions: 100 mM KCl, 10 mM SC, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 6.8. [HIV TAR RNA] = 1 µM/strand. [Ligand] = 1 µM.

Under matched conditions, 5 displayed the strongest thermal stabilization with a ΔTm of 10.1 °C (Fig. 2A,B) at a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1 (5 : HIV TAR RNA). Strong thermal stabilization by 5, highlights the synergistic role of covalently linked ligands 4 and 1.

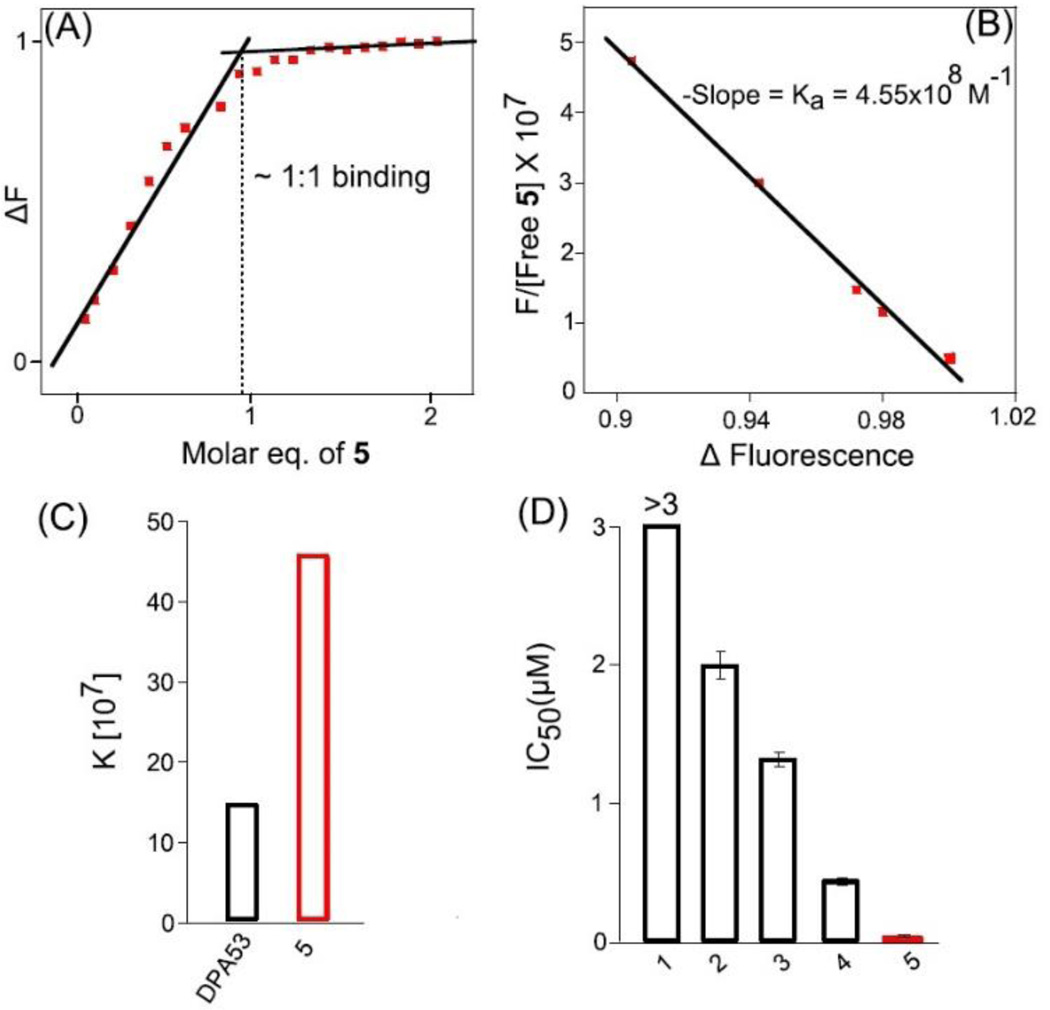

Fluorescent intercalator displacement assay (FID)41 was used to determine the relative binding of various ligands against HIV TAR RNA. Briefly, 50 nm/strand HIV TAR RNA was incubated with 1.25 µM Ethidium Bromide (EtBr). The concentration ratio of exogenous intercalator to RNA ensures a small fraction of the former is bound (<20%) to RNA. The solution was then titrated in a dose dependent manner with various ligands. The relative change in fluorescence was plotted as a function of the concentration of ligand. The curve was fit using a sigmoidal fit to extract the midpoint of the titration (IC50). The IC50 for 5 was 33±7 nM which was the lowest among all the ligands. The IC50 for 5 was ~14 fold lower than the control ligand (4). The trend for IC50 values for various ligands corroborate well with their ΔTm values. A dose dependent FID titration of 5 with TAR RNA-EtBr complex was employed to assess the apparent binding affinity between 5 and HIV TAR RNA. The linear fit of the pre and post saturation curves afforded the binding stoichiometry of 1:1 (HIV TAR RNA: 5). Subsequent Scatchard analysis41 of the binding curve yielded an association constant of 4.6 × 108 M-1 (Fig. 3B and 3C). The association constant for 5 towards HIV TAR RNA was ~4 times higher than the highest affinity neomycin dimer (DPA 53) we reported earlier (Fig. 3C). 20

Figure 3.

FID derived binding characterization of indicated ligands with HIV TAR RNA. (A) Relative change in the fluorescence intensity of HIV-TAR RNA-EtBr complex in the presence of 5 in a dose dependent manner. (B) Scatchard analysis to extract an association constant between HIV TAR RNA and 5. (C) Comparison of the association constants of 5 and DPA 5320 determined using Scatchard analysis of FID assay. (D) Comparison of the IC50 values extracted for the indicated ligands determined using FID assay. [HIV TAR RNA] = 1 µM/strand.

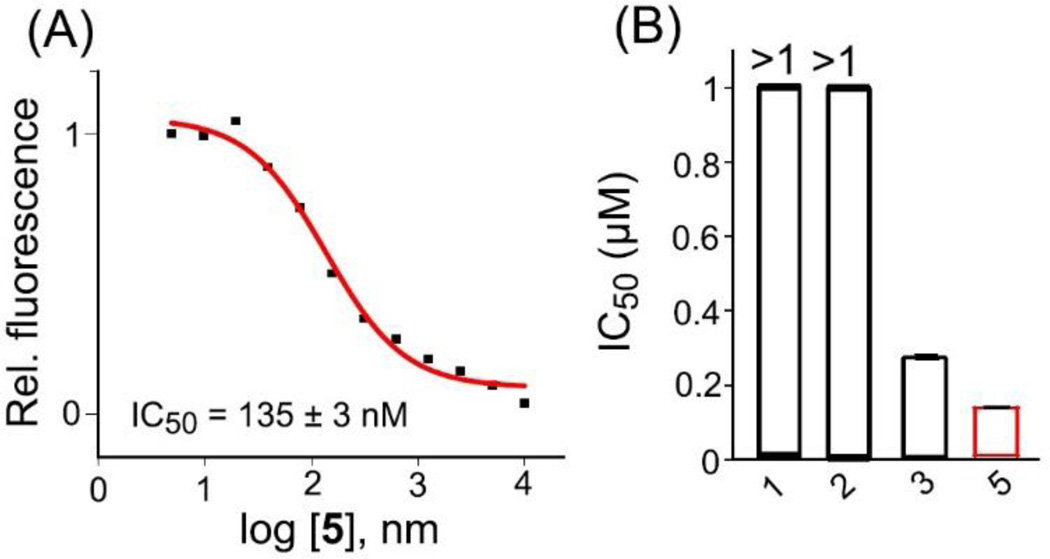

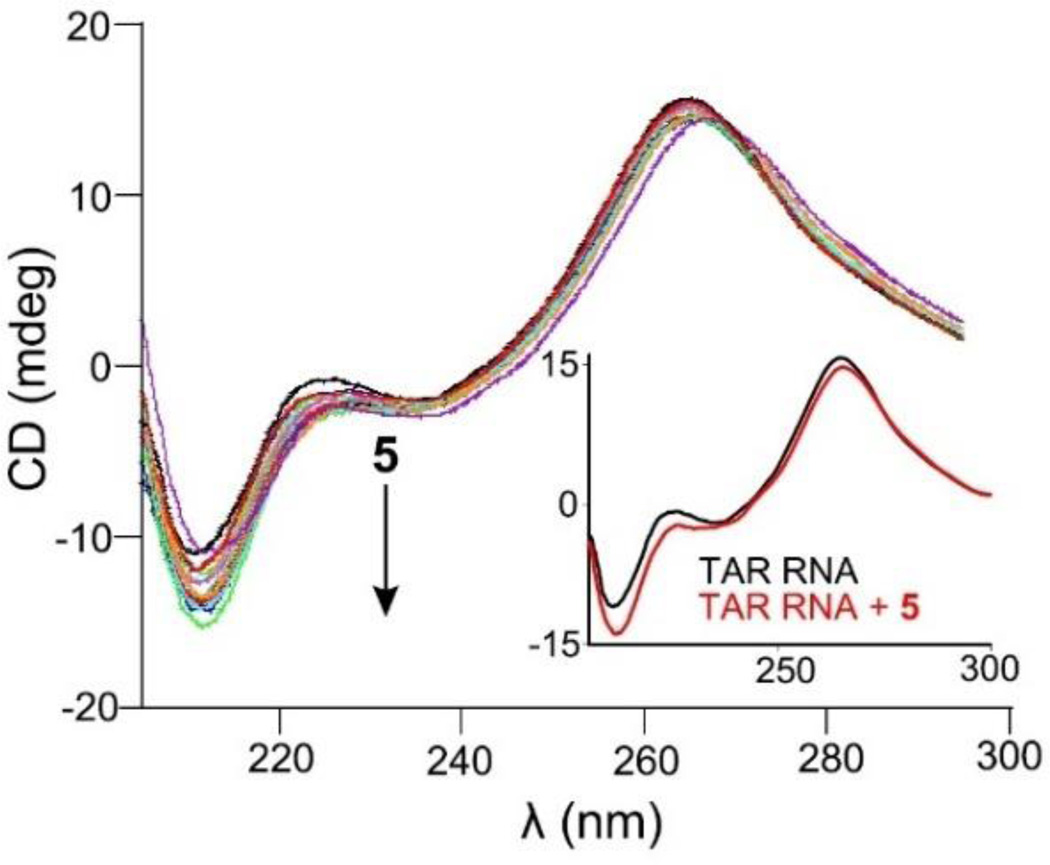

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) competitive binding assay was utilized to assess the antagonist activity of 5 towards HIV TAR RNA-TAT assembly. Briefly, the preformed complex of fluoresce in-labeled TAT 49–57 HIV TAR RNA was titrated with 5 in a dose dependent manner which resulted in a decrease in the fluorescence intensity (Fig. 4). The curve was fitted using sigmoidal fit to extract the IC50 value for 5 which was (135±3) nM. The IC50 for 5 was nearly two-fold better than neomycin benzimidazole conjugate (3). It is evident from both FRET and FID assays that 5 is a better antagonist of HIV TAR RNA-TAT assembly than its individual building units. To probe the binding induced conformational changes, a circular dichroism (CD) titration was conducted. Incremental addition of 5 to TAR RNA led to small changes in the CD spectrum, however the overall conformation of TAR RNA was conserved (Fig. 5). The CD spectrum of HIV TAR RNA is typically characterized with a positive band at 265 nm and a negative band at 210 nm. A continuous decrease in the magnitude of ellipticity was observed for the band at 210 nm upon addition of 5. Additionally, a slight red shift was observed for the band at 265 nm. The shift indicates that 5 moderately drive the conformation of HIV TAR RNA towards A-form likely locking the TAR RNA in a conformation not conducive for tat protein binding.

Figure 4.

Direct measure of the antagonist activities of indicated ligands towards HIV TAR RNA-TAT assembly. (A) Representative sigmoidal fit to extract the IC50 for 5 using FRET competition binding assay. (B) Comparison of the IC50 values for the indicated ligands determined using FRET competitive binding assay. [HIV TAR RNA] = 100 nM/strand, [TAT-fluoresce in] = 100 nM/strand.

Figure 5.

CD spectra depict the change in conformation of HIV TAR RNA induced by 5. The inset corresponds to the CD spectrum of HIV TAR RNA in the absence (black) and presence (red) of 5 at an equimolar ratio.

Neomycin has been shown to bind at three independent sites on TAR; namely the trinucleotide bulge, lower stem below the bulge, and the hairpin loop region.18 We approached such multi-recognition using a tridentate ligand. The tridentate ligand, compound 5, constitutes two neomycin units and a benzimidazole ligand attached via a linker. We speculate that two neomycin units bind in the lower stem and the trinucleotide bulge of TAR while the benzimidazole potentially binds at the preferential Hoechst 33258 binding site below the hairpin loop (See Figure 1). Alternatively, one of the neomycin units could occupy the loop with the other binding to either trinculeotide bulge or lower stem of TAR with benzimidazole still occupying the Hoechst 33258 binding site below the hairpin loop. However, such binding is expected to be disfavoured by steric constraints.

In conclusion, a multiple recognition approach has been practiced using a neomycin dimer benzimidazole conjugate to target multiple binding sites on HIV TAR RNA. A number of biophysical studies including FID assay, CD, and UV thermal denaturation verified enhanced binding of neomycin dimer benzimidazole towards HIV TAR RNA. The study presented here will aid in development of new approaches for novel antagonists of HIV TAR RNA-TAT assembly via multiple binding site approach, in addition to opening up new avenues in multivalent ligand design to target novel RNA structures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant (R15CA125724, and GM097917) to D.P.A. We thank Dr. Suresh Pujari (Clemson University) for obtaining HPLC chromatogram of compound 5.

Footnotes

Footnotes relating to the title and/or authors should appear here.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here].

Notes and reference

- 1.HIV U. UNAIDS. 2015:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones KA, Peterlin BM. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1994;63:717–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.003441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rana TM, Jeang K. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;365:175–185. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailly C, Colson P, Houssier C, Hamy F. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1460–1464. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.8.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratmeyer LS, Vinayak R, Zon G, Wilson WD. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:966–968. doi: 10.1021/jm00083a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dassonneville L, Hamy F, Colson P, Houssier C, Bailly C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4487–4492. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lind KE, Du Z, Fujinaga K, Peterlin BM, James TL. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao J, Frankel AD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992;89:2723–2726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang S, Tamilarasu N, Ryan K, Huq I, Richter S, Still WC, Rana TM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96:12997–13002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.12997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Athanassiou Z, Patora K, Dias RLA, Moehle K, Robinson JA, Varani G. Biochemistry (N. Y.) 2007;46:741–751. doi: 10.1021/bi0619371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson A, Leeper TC, Athanassiou Z, Patora-Komisarska K, Karn J, Robinson JA, Varani G. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:11931–11936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900629106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu J, Nguyen L, Zhao L, Xia T, Qi X. Biochemistry. 2015;54:3687–3693. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mei H, Mack DP, Galan AA, Halim NS, Heldsinger A, Loo JA, Moreland DW, Sannes-Lowery KA, Sharmeen L, Truong HN, Czarnik AW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1997;5:1173–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(97)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranjan N, Kumar S, Watkins D, Wang D, Appella DH, Arya DP. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:5689–5693. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nahar S, Ranjan N, Ray A, Arya DP, Maiti S. Chem. Sci. 2015;6(10):5837–5846. doi: 10.1039/c5sc01969a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willis B, Arya DP. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:2327–2332. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ranjan N, Arya DP. Molecules. 2013;18:14228–14240. doi: 10.3390/molecules181114228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranjan N, Davis E, Xue L, Arya DP. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:5796–5798. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42721h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willis B, Arya DP. Biochemistry. 2010;49:452–469. doi: 10.1021/bi9016796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue L, Xi H, Kumar S, Gray D, Davis E, Hamilton P, Skriba M, Arya DP. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5540–5552. doi: 10.1021/bi100071j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw NN, Xi HJ, Arya DP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:4142–4145. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue L, Ranjan N, Arya DP. Biochemisry. 2011;50:2838–2849. doi: 10.1021/bi1017304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willis B, Arya DP. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10217–10232. doi: 10.1021/bi0609265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue L, Charles I, Arya DP. Chem Commun. 2002:70–71. doi: 10.1039/b108171c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arya DP, Coffee RL., Jr Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:1897–1899. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arya DP, Lane Coffee JR, Willis B, Abramovitch AI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5385–5395. doi: 10.1021/ja003052x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arya DP, Coffee RL, Jr, Charles I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11093–11094. doi: 10.1021/ja016481j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arya DP, Xue L, Willis B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:10148–10149. doi: 10.1021/ja035117c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arya DP, Micovic L, Charles I, Coffee RL, Jr, Willis B, Xue L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:3733–3744. doi: 10.1021/ja027765m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arya DP. Top Curr Chem. 2005;253:149–178. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xi H, Gray D, Kumar S, Arya DP. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2269–2275. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ranjan N, Andreasen KF, Kumar S, Hyde-Volpe D, Arya DP. Biochemistry. 2010;49(45):9891–9903. doi: 10.1021/bi101517e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arya DP. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44(2):134–146. doi: 10.1021/ar100113q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xi HJ, Davis E, Ranjan N, Xue L, Hyde-Volpe D, Arya DP. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9088–9113. doi: 10.1021/bi201077h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sannes-Lowery KA, Mei H, Loo JA. Intl. J. Mass Spectrom. 1999;193:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang S, Huber PW, Cui M, Czarnik AW, Mei H. Biochemistry (N. Y.) 1998;37:5549–5557. doi: 10.1021/bi972808a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar S, Kellish P, Robinson WE, Wang D, Appella DH, Arya DP. Biochemisry. 2012;51:2331–2347. doi: 10.1021/bi201657k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar S, Arya DP. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:4788–4792. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li C, Ge Z, Liu H, Liu S. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:4001–4013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boger DL, Fink BE, Brunette SR, Tse WC, Hendrick MP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5878–5891. doi: 10.1021/ja010041a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.