Abstract

Background

The use of electronic interventions (e-interventions) may improve treatment of alcohol misuse.

Purpose

To characterize treatment intensity and systematically review the evidence for efficacy of e-interventions, relative to controls, for reducing alcohol consumption and alcohol-related impairment in adults and college students.

Data Sources

MEDLINE (via PubMed) from January 2000 to March 2015 and the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and PsycINFO from January 2000 to August 2014.

Study Selection

English-language, randomized, controlled trials that involved at least 50 adults who misused alcohol; compared an e-intervention group with a control group; and reported outcomes at 6 months or longer.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers abstracted data and independently rated trial quality and strength of evidence.

Data Synthesis

In 28 unique trials, the modal e-intervention was brief feedback on alcohol consumption. Available data suggested a small reduction in consumption (approximately 1 drink per week) in adults and college students at 6 months but not at 12 months. There was no statistically significant effect on meeting drinking limit guidelines in adults or on binge-drinking episodes or social consequences of alcohol in college students.

Limitations

E-interventions that ranged in intensity were combined in analyses. Quantitative results do not apply to short-term outcomes or alcohol use disorders.

Conclusion

Evidence suggests that low-intensity e-interventions produce small reductions in alcohol consumption at 6 months, but there is little evidence for longer-term, clinically significant effects, such as meeting drinking limits. Future e-interventions could provide more intensive treatment and possibly human support to assist persons in meeting recommended drinking limits.

Primary Funding Source

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Alcohol misuse is a broad term that incorporates a spectrum of severity, ranging from hazardous use that exceeds guideline limits to misuse severe enough to meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder (AUD). Table 1 provides a glossary of terms along this spectrum. To address the impairment related to alcohol misuse (1) from a public health perspective, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening and brief intervention (2, 3), an approach that reduces alcohol consumption by 3 to 4 drinks per week for up to 12 months after the intervention (4). Screening and brief intervention sessions typically consist of brief assessment, followed by personalized normative feedback and advice to adhere to recommended drinking limits, which are typically defined for men as consuming 4 standard drinks or fewer (1 drink equals 14 g of alcohol) on any day and 14 drinks or fewer per week and for women as 3 drinks or fewer on any day and 7 drinks or fewer per week (5).

Table 1.

Glossary of Terms on the Spectrum of Alcohol Misuse*

| Term | Definition† |

|---|---|

| Risky or hazardous use | Excess daily consumption (>4 drinks/d in men or >3 drinks/d in women and men aged ≥65 y) or excess total consumption (>14 drinks/wk in men or >7 drinks/wk in women and men aged ≥65 y) associated with increased risk for health problems. |

| Harmful use | A pattern of drinking that is already causing damage to health. The damage may be physical (e.g., liver damage) or mental (e.g., depressive episodes). |

| Alcohol abuse‡ | A maladaptive pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress (e.g., failure to fulfill major obligations). Continued use despite persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by alcohol. |

| Alcohol dependence‡ | A maladaptive pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, which may include the following symptoms associated with alcoholism or addiction: tolerance, withdrawal, excessive amounts consumed or time spent drinking, unsuccessful attempts to decrease use, or a pattern that continues despite persistent problems caused by or associated with alcohol. |

| AUD§ | A person continues a pattern of alcohol use despite >2 clinically significant alcohol-related problems in the following areas: impaired control over use (e.g., inability to decrease consumption), social impairment (e.g., failing to fulfill an obligation or foregoing a favorite activity), health consequences (physical or mental), and physiologic dependence (e.g., cravings). The disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number of symptoms. |

AUD = alcohol use disorder; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition.

Alcohol misuse (sometimes called unhealthy alcohol use) is an umbrella term for a spectrum of potentially problematic patterns of alcohol use. This table was adapted with permission from reference 4 and uses terminology from DSM-IV for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence and from DSM-5 for AUD. In collaboration with Dr. Jonas, we abbreviated and updated the table in the original source to reflect DSM-5 terminology.

Reference time period of 1 y.

DSM-IV criteria. Not all exact criteria are listed.

DSM-5 criteria. Not all exact criteria are listed. This new category integrates the 2 DSM-IV disorders “alcohol abuse” and “alcohol dependence” into a single disorder for DSM-5.

Alcohol misuse counseling, including screening and brief intervention, is constrained by barriers, such as inadequate funding, time, and trained personnel (6–8). In addition, the efficacy of screening and brief intervention in settings other than primary care is not established (9). Electronic interventions (e-interventions) may address some barriers and extend the reach of treatment by reducing demands for clinician time and clinic space while increasing the number of persons who can access treatment and their frequency of accessing treatment. With 87% of the U.S. population using the Internet (10), e-interventions can potentially reach persons with drinking problems who wish to remain anonymous, lack the time or resources for traditional therapy, need to access therapy during nonstandard business hours, or live in rural areas (11, 12).

Previous systematic reviews that evaluated e-interventions for alcohol misuse have generally found short-term benefits (13–17), but examination of maintenance of intervention effects is needed. Two recent systematic reviews have reported follow-up outcomes at 6 months or longer. However, they did not analyze college student and noncollege adult trials separately (13, 17), despite distinctions between these groups in patterns of alcohol consumption and associated impairment (18, 19). In addition, previous systematic reviews have generally not reported on the efficacy of e-interventions for AUDs (13–17) or provided detailed descriptions of treatment intensity, including amount and type of human support (13–14, 17).

To characterize treatment intensity for alcohol misuse and evaluate evidence for their efficacy, we did a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials (RCTs). We compared e-interventions for alcohol misuse with inactive or minimal intervention controls for reducing alcohol consumption and alcohol-related impairment in adults and college students for 6 months or longer.

METHODS

We followed a standard protocol in which key steps, such as eligibility assessment, data abstraction, and risk of bias, were piloted and discussed by team members. A technical report that fully details our methods and results is available on the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Web site (20).

We addressed 3 research questions. First, for e-interventions that targeted adults who misused alcohol or had an AUD, what level, type, and method of user support were provided; by whom; and in what clinical context? Second, for adults who misused alcohol but did not meet diagnostic criteria for an AUD, what were the effects of e-interventions compared with inactive controls? Third, for adults who were at high risk for or who had an AUD, what were the effects of e-interventions compared with inactive controls? Appendix Table 1 (available at www.annals.org) provides individual trial characteristics.

Data Sources and Searches

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed), the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and PsycINFO from 1 January 2000 to 18 August 2014 for peer-reviewed, English-language RCTs. We used medical subject heading terms and selected free-text terms for alcohol misuse, therapy types of interest, and electronic delivery. The MEDLINE search was updated on 25 March 2015. The search strategies are shown in Appendix Table 2 (available at www.annals.org). We reviewed bibliographies of included trials and applicable systematic reviews for missed publications (14–15, 21–25). To assess for publication bias, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov for trials that met our eligibility criteria (26) and found 2 trials that were completed at least 1 year before our literature search but were unpublished.

Trial Selection

Two reviewers used prespecified eligibility criteria to assess all titles and abstracts. The full text of potentially eligible trials was retrieved for further evaluation. We included RCTs that compared e-interventions with inactive or active controls in patients with alcohol misuse or an AUD. We reported effects on alcohol consumption or another eligible outcome at 6 months or longer (Appendix Table 3, available at www.annals.org). E-interventions could be delivered by CD-ROM, online, mobile applications, or interactive voice response (a technology that allows a computer to interact with humans using voice and signaling over analog telephone lines). Two investigators assessed for eligibility, and disagreements were resolved by team discussion or a third reviewer.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data abstractions were done by 1 reviewer and confirmed by a second. We assessed each trial’s risk of bias using criteria specific for RCTs and summarized overall risk of bias as low, moderate, or high using the approach described by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (26). The Appendix (available at www.annals.org) shows questions and the rationale for quality ratings criteria, and detailed quality ratings for each included trial are displayed in Appendix Table 4 (available at www.annals.org).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We evaluated the overall strength of evidence for selected outcomes as high, moderate, low, or insufficient using the domains of directness, risk of bias, consistency and precision of treatment effects, and risk of publication bias (27). Table 2 shows strength-of-evidence domain and overall ratings.

Table 2.

SOE, by Outcome Domains*

| Outcome | SOE Domains

|

6-mo Effect Estimate (95% CI); Trial Composition | SOE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies, n | Patients, n | Study Design | Risk of Bias | Consistency | Directness | Precision | Publication Bias | |||

| E-intervention vs. control in persons who screened positive for alcohol misuse | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Alcohol consumption (g/wk) | 18 | 7484 | RCT | Moderate | Consistent | Direct | Precise | None detected | MD, −16.7 g/wk (−27.6 to −5.8 g/wk)†; 5 trials of adults | Moderate |

| MD, −11.7 g/wk (−19.3 to −4.1 g/wk); 11 trials of students | Moderate | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Alcohol consumption (met limits) | 5 | 4313 | RCT | Low | Some inconsistency | Direct | Imprecise | None detected | RR, 1.22 (0.79 to 1.89); 4 trials of adults | Low |

| OR, 1.53 (1.09 to 2.17); 1 trial of students | Low | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Alcohol consumption (binge drinking) | 7 | 5043 | RCT | Low | Some inconsistency | Some indirectness | Precise | None detected | Difference, −1.9% (−10.4% to 6.6%) (49) β, 0; SE, 0.01 (48); 2 trials of adults |

Moderate |

| MD, −0.1 episodes (−0.6 to 0.4 episodes); 5 trials of students | Moderate | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Alcohol social problems | 11 | 5234 | RCT | Low | Some inconsistency | Some indirectness | Precise | None detected | β, 0.24; SE, 0.41; 1 trial of adults | Low |

| SMD, 0 (−0.10 to 0.10); 10 trials of students | Moderate | |||||||||

| E-intervention vs. control in persons with an AUD | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Alcohol consumption | 3 | 533 | RCT | Moderate | Consistent | Direct | Imprecise | None detected | Increase in abstinence for adults with smartphone e-intervention: OR, 1.94 (1.14 to 3.31) | Low |

| No difference with IVR or computerized feedback | Insufficient | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Alcohol social problems | 2 | 409 | RCT | Moderate | NA | Direct | Imprecise | None detected | No difference in adults | Low |

AUD = alcohol use disorder; e-intervention = electronic intervention; IVR = interactive voice response; MD = mean difference; NA = not applicable; OR = odds ratio; RCT = randomized, controlled trial; RR = relative risk; SMD = standardized mean difference; SOE = strength of evidence.

When evaluating the overall strength of evidence, we considered a difference of 3 standard U.S. drinks/wk or an SMD ≥0.4 as clinically significant and defined precise effects as those with 95% CIs that excluded smaller effects.

Results are from a sensitivity analysis that included only trials rated as low to moderate risk of bias because this analysis produced a more precise estimate.

While synthesizing abstracted data, we classified the e-interventions according to the level of supplementary human support. Level 1 included e-interventions with no human support; level 2 included e-interventions supplemented by noncounseling interactions with study staff, such as technical support; and level 3 included e-interventions supplemented by counseling with trained staff.

The key outcomes were alcohol consumption, meeting recommended alcohol consumption limits, rates of binge drinking, alcohol-related health, social or legal problems, health-related quality of life, and adverse effects. When at least 3 trials reported a given outcome, we did a meta-analysis. We combined continuous outcomes by using mean differences (MDs) or standardized MDs when instruments varied and combined dichotomous outcomes by using risk ratios in random-effects models. Alcohol consumption was converted to a common unit (grams per week) across trials. We used metafor package in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) (28) to calculate summary estimates of effect, stratified by condition and sample (college students vs. adults), at 6 and 12 months, with Knapp–Hartung adjustment of SEs of the estimated coefficients (29, 30). When at least 3 trials were rated as low or moderate risk of bias, we excluded trials rated as high risk of bias and did sensitivity analyses to compute summary estimates.

We evaluated statistical heterogeneity in treatment effects by using the Cochran Q and I2 statistics. We planned subgroup analyses, specifying a priori, to explore the following potential sources of heterogeneity: follow-up rates, treatment dose, and the level of human support given with the intervention. However, these analyses could not be done because subgroups did not meet the prespecified minimum of 4 trials per subgroup (31). When there were too few trials for quantitative synthesis, we analyzed the data qualitatively, focusing on identifying novel aspects of the e-intervention and patterns of efficacy.

Role of the Funding Source

This review was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The funding source had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

RESULTS

We reviewed 100 full-text articles of the 856 citations that were screened and identified 28 trials that met eligibility criteria (Appendix Figure 1, available at www.annals.org). The populations were divided between college students (n = 14) and noncollege adults (n = 14). Only 3 trials specifically recruited participants who were at high risk for or who had an AUD. The other 25 trials recruited participants who misused alcohol. A single trial used a mobile device as the delivery platform (32). Strength of evidence for each outcome is summarized in Table 2.

E-Intervention Characteristics and Support

Seventeen trials were “minimal” support (level 1) interventions that used no human support, 8 used “low” noncounseling support (level 2), and 3 included “moderate or high” (level 3) counseling support. Summary characteristics and support for e-interventions are listed in Table 3. Most trials examined a 1-time intervention (n = 19), delivered online or at a desktop computer (n = 24), that compared a person’s alcohol consumption with his or her peer group norm (n = 19). When supplementary human support was used (for 7 trials that enrolled adults and 3 that enrolled students), it was typically limited, consisting only of technical support from a research assistant in more than one half of the cases (for 4 trials that enrolled adults and 3 that enrolled students). However, therapeutic support varied substantially, with some e-interventions supplemented by 1.5 to 6.5 hours of support (33–36).

Table 3.

Characteristics of E-Interventions*

| Characteristic | Adult Trials (n = 14) | Student Trials (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|

| Level of support | ||

|

| ||

| 1 | 7 | 11 |

|

| ||

| 2 | 4 | 3 |

|

| ||

| 3 | 3 | 0 |

|

| ||

| Number of sessions | ||

| 1 | 7 | 12 |

|

| ||

| >1 | 6† | 2‡ |

|

| ||

| NR | 1 | 0 |

| Session duration | ||

|

| ||

| Median (range), min | 10 (3–90) | 25 (2–50) |

|

| ||

| NR | 7 | 5 |

|

| ||

| NA§ | 2 | 0 |

|

| ||

| Intervention | ||

| IVR | 2 | 0 |

|

| ||

| Not named | 3 | 5 |

|

| ||

| e-CHUG | 0 | 2 |

|

| ||

| BASICS | 0 | 3 |

|

| ||

| What Do You Drink | 0 | 2 |

|

| ||

| Programs used only once‖ | 9 | 2 |

|

| ||

| Delivery mode | ||

| Accessed on the Internet | 9 | 12 |

|

| ||

| Software on laptop or desktop | 1 | 2 |

|

| ||

| Mobile device¶ | 1 | 0 |

|

| ||

| IVR | 2 | 0 |

|

| ||

| NR | 1 | 0 |

| Delivery location | ||

|

| ||

| Off-site** | 5 | 6 |

|

| ||

| On-site†† | 3 | 4 |

|

| ||

| NR | 6 | 4 |

|

| ||

| Content of e-intervention | ||

| Brief intervention | 10 | 8 |

|

| ||

| PNF‡‡ | GS: 6 Non-GS: 1 NR: 1 |

GS: 10 Non-GS: 2 |

|

| ||

| Psychoeducation | 9 | 7 |

|

| ||

| Alcohol-specific, n/N | 4/9 | 4/7 |

|

| ||

| Goal setting | 7 | 3 |

|

| ||

| Negative consequences | 5 | 6 |

|

| ||

| Skills training | 3 | 2 |

|

| ||

| Self-monitoring | 4 | 0 |

|

| ||

| Tailored feedback | 3 | 4 |

|

| ||

| Relapse prevention | 2 | 0 |

|

| ||

| Other techniques§§ | 10 | 3 |

| Comparator | ||

|

| ||

| WL‖‖ | 5 | 8 |

|

| ||

| Attention/information control | 6 | 5 |

|

| ||

| Treatment as usual | 3 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Low | 3 | 5 |

|

| ||

| Moderate | 7 | 8 |

|

| ||

| High | 4 | 1 |

BASICS = Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students; e-CHUG = Electronic Check-up to Go; e-intervention = electronic intervention; GS = gender-specific; IVR = interactive voice response; NA = not applicable; NR = not reported; PNF = personalized normative feedback; WL = wait list.

Values are numbers unless otherwise indicated.

2 daily IVR.

2–5 sessions.

IVR.

In adult trials: Balance; feedback, responsibility, advice, menu of options, empathy, and self-efficacy; eScreen.se; www.drinktest.nl; Down Your Drink; Check Your Drinking; minderdrinken.nl; Addiction-Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System; and Everything With Limits. In student trials: Tertiary Health Research Intervention Via Email and College Drinker’s Check-up.

Smartphone.

For example, home or IVR.

For example, clinic or classroom.

For adults, the comparison group was usually a national population (n = 3) or age-matched adults (n = 3); for students, the comparison group was usually student peers (n = 7).

Used once. For adults: cognitive behavioral therapy, computer monitoring, e-mail, global positioning system, homework, taking responsibility, text messaging, and values clarification. For students: homework and decisional balance exercise.

Includes true WL, assessment only, and no treatment.

The modal intervention was a single session designed to moderate alcohol consumption in persons who screened positive for alcohol misuse on an alcohol questionnaire. Five trials offered 2 to 5 sessions with the e-intervention (for 3 trials that enrolled adults and 2 that enrolled students) (37–40), 1 trial offered 62 sessions (38), and 3 trials (32, 41, 42) offered participants unlimited access to the program. The most common e-intervention component was personalized normative feedback (for 8 trials that enrolled adults and 12 that enrolled students), but the breadth, intensity, and type of e-interventions that we combined in meta-analyses were heterogeneous. Other common treatment techniques were goal setting (for 7 trials that enrolled adults and 3 that enrolled students), psychoeducation (for 9 trials that enrolled adults and 7 that enrolled students), and coping skills training (for 3 trials that enrolled adults and 2 that enrolled students). E-interventions also varied in duration, ranging from a single, 2-minute interaction to as many as 62 interactions for more than 1 year (36). Comparators ranged from only wait list or assessment to attention or information controls.

All trials that used relatively intensive human support (n = 3) were conducted in adults (33–35), and 2 (34, 35) used interactive voice response. One intervention (34) used a motivational interview followed by 60 days of interactive voice response with reminder calls as needed and two 10- to 15-minute follow-up counseling sessions. Another intervention used 180 days of interactive voice response with 1 group that used reminder calls as needed (35). One intervention used four 30- to 40-minute follow-up phone calls for counseling from trained psychologists (33).

E-Interventions for Hazardous Alcohol Use Compared With Inactive Control

We included 25 trials of e-interventions versus inactive controls in participants who misused alcohol. Three trials of adults were rated as low, 7 as moderate, and 4 as high risk of bias. Five trials of students were rated as low, 8 as moderate, and 1 as high risk of bias.

Alcohol Consumption

The mean baseline alcohol consumption in 7 trials that enrolled adult samples ranged from 129 to 436 grams per week (median, 235 grams per week) (36, 40, 43–47), including 2 rated as high risk of bias. E-interventions were associated with no statistically significant effect on alcohol consumption at 6-month follow-up (MD, −25.0 grams per week [95% CI, −51.9 to 1.9]) (Figure 1); heterogeneity was moderate (Q = 11.1; P = 0.085; I2 = 46.1%) and likely due to 1 trial rated as high risk of bias that included a more intensive treatment (44). A sensitivity analysis that was limited to 5 trials rated as low or moderate risk of bias found a small, statistically significant reduction in alcohol consumption with no heterogeneity (MD, −16.7 grams per week [CI, −27.6 to −5.8]; I2 = 0%). In 5 trials that reported 12-month follow-up (33, 42, 43, 45, 47), e-interventions were not associated with a statistically significant reduction in alcohol consumption (MD, −8.6 grams per week [CI, −53.7 to 36.5]); heterogeneity in treatment effects were high (Q = 14.8; P = 0.005; I2 = 72.9%) and likely due to increases in drinking in the e-intervention group in 1 trial (45). Removal of the 1 trial rated as high risk of bias from 12-month follow-up analyses also resulted in no statistically significant effect on alcohol consumption (MD, −5.5 grams per week [CI, −79.0 to 68.1]; I2 = 79%).

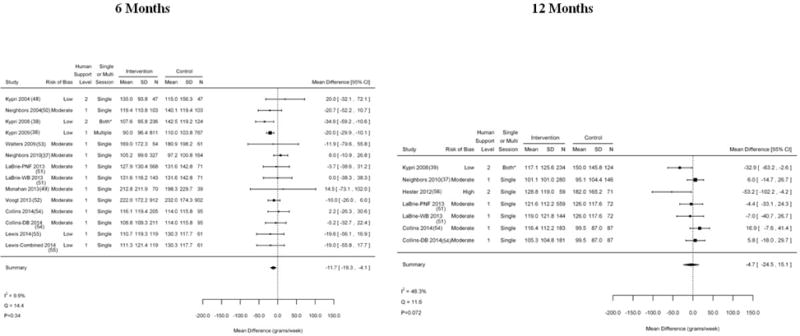

Figure 1.

Alcohol consumption at 6 and 12 mo in studies of adults. MD = mean difference; NR = not reported. * Means and SDs were not available because only MD and CI were given.

In college students, mean alcohol consumption at baseline ranged from 85 to 439 grams per week (median, 183 grams per week). In 11 trials rated as low to moderate risk of bias that used 14 comparisons (37–39, 48–55), e-interventions were associated with a small, statistically significant reduction in alcohol consumption at 6-month follow-up (MD, −11.7 grams per week [CI, −19.3 to −4.1]) (Figure 2), with low heterogeneity in treatment effects (Q = 14.4; P = 0.34; I2 = 9.9%). In 5 trials that used 7 comparisons of 12-month follow-up assessments of alcohol consumption in college students (37, 39, 51, 54, 56), including 1 trial rated as high risk of bias, analyses revealed no statistically significant reduction in alcohol consumption (MD, −4.7 grams per week [CI, −24.5 to 15.1]), with moderate heterogeneity in treatment effects (Q = 11.6; P = 0.072; I2 = 48.3%). Removal of the trial rated as high risk of bias produced a similarly statistically insignificant effect (MD, −0.3 grams per week [CI, −17.5 to 16.8]) but with lower heterogeneity (Q = 7.2; P = 0.21; I2 = 30%).

Figure 2.

Alcohol consumption at 6 and 12 mo in studies of college students. DB = decisional balance; MD = mean difference; PNF = personalized normative feedback; WB = Web-based. * The intervention group had 2 options (1 screening and brief intervention session or 3 screening and brief intervention sessions), so it is labeled “both.”

Drinking Limit Guidelines

In 4 trials that reported proportion of participants meeting drinking limit guidelines at 6 months (40, 43, 44, 57), including 2 trials rated as high risk of bias, e-interventions had no statistically significant effect on meeting guidelines (risk ratio, 1.22 [CI, 0.79 to 1.89]) (Appendix Figure 2, available at www.annals.org), with moderate heterogeneity in effect sizes (Q = 6.5; P = 0.088; I2 = 54.2%) that was influenced most heavily by 1 trial rated as high risk of bias (44). One trial rated as low risk of bias in students (38) reported elevated probability of meeting drinking limits in the e-intervention group at 6 months (odds ratio, 1.53 [CI, 1.09 to 2.17]). No trials reported on meeting drinking limits at 12 months.

Binge Drinking

In adults, 1 trial rated as moderate risk of bias found similar proportions of binge drinkers in the e-intervention (23%) and treatment-as-usual groups (25%) at 6 months (difference, −1.9% [CI, −10.4% to 6.6%]) (47). A trial rated as low risk of bias also found similar proportions of binge drinkers in the e-intervention (47%) and control groups (45%) at 6 months (β = 0; SE = 0.01; P = 0.76) (46).

In 5 trials rated as low to moderate risk of bias in students (37, 48, 49, 52), e-interventions resulted in no statistically significant reduction in binge drinking (MD, −0.1 episodes [CI, −0.6 to 0.4]) at 6-month follow-up. Effect sizes had moderate heterogeneity (Q = 8.8; P = 0.066; I2 = 55%); 1 trial rated as low risk of bias that studied human support reported significant effects (44).

Social Consequences

In the only trial rated as low risk of bias in adults (47), self-reported social problems were similar in the e-intervention (mean, 5.9 points on the Short Inventory of Problems questionnaire [SD, 10.2]) and treatment-as-usual groups (mean, 6.5 points [SD, 9.3]). In 10 student trials rated as low to moderate risk of bias reporting 6-month follow-up data (37–39, 48, 50, 53, 58), e-interventions had no statistically significant effect on social consequences (standardized MD, 0 points on the self-reported social consequences measure [CI, −0.10 to 0.10]); heterogeneity was low to moderate (Q = 20.1; P = 0.064; I2 = 40%). In the 6 trials that reported 12-month follow-up data (37, 39, 51, 54, 56, 58), e-interventions had no statistically significant effect on social consequences (standardized MD, 0.01 points [CI, −0.19 to 0.22]); these trials had high heterogeneity (Q = 30.0; P < 0.001; I2 = 77%) that was due in part to an e-intervention trial rated as low risk of bias that included human support (39). Removal of the trial rated as high risk of bias produced similar results (MD, −0.02 points [CI, −0.24 to 0.20]; I2 = 77%).

Other Outcomes

No trials reported sufficient data to analyze effects on health-related quality of life, alcohol-related health problems, medical utilization, or adverse effects.

Effects of E-Interventions in Adults With Likely Diagnosis of an AUD

Three trials (2 rated as moderate and 1 as high risk of bias) that we describe qualitatively compared e-interventions with inactive controls in patients with a likely diagnosis of an AUD. In a subgroup of patients with alcohol dependence recruited from primary care, computerized feedback was combined with up to four 30- to 40-minute motivational interviewing phone counseling sessions conducted by psychologists (33). At 12-month follow-up, the intervention and control groups did not differ in alcohol consumption (P = 0.62) or binge drinking (P = 0.69).

A trial that enrolled patients who completed residential AUD treatment included an interactive voice-response system and 3 online modules on commitment to abstinence, motivation, and cognitive behavioral advice, with calls from the study coordinator prompted by 2 missed days of interactive voice response or participant request (35). At 6-month follow-up, abstinence was self-reported in 66.7% and 72.2% of intervention and control participants, respectively (difference, −5.6 percentage points [CI, −36.7 to 25.6]).

In another trial of patients who were recently discharged from residential AUD treatment, patients received a smartphone with an AUD application and data plan (32). The application included guided relaxation exercises and alerts initiated by the Global Positioning System when participants approached high-risk locations. Counselors received assessments of relapse risk and could intervene by phone when risk was elevated. At 12 months, participants in the e-intervention group had increased odds of abstinence (odds ratio, 1.94 [CI, 1.14 to 3.31]) and decreased frequency of risky drinking (defined as >4 drinks per day for men or >3 drinks per day for women) (MD, −1.47 days per month [CI, −0.13 to −2.81]).

DISCUSSION

Compared with controls, we found limited evidence for small effects of e-interventions (consumption of approximately 1 drink less per week) alcohol outcomes in adults and college students who screened positive for hazardous alcohol use at 6 months or longer, with diminishing effects at 12 months. There were no clinically or statistically significant effects on meeting drinking limit guidelines, binge-drinking frequency, or social consequences. Few data were available on e-interventions for AUDs. Although effects suggested a trend toward benefits from e-interventions, such small effects alone may not be sufficient to improve health and social consequences of drinking, especially in the absence of data indicating that e-interventions effectively resulted in meeting drinking limit guidelines or reducing frequency of binge drinking.

Our findings differ from those of a review of in-person screening and brief intervention, which found that behavioral counseling decreased alcohol consumption by 3 to 4 drinks per week and that 11% more persons had maintained recommended drinking limits at 12-month follow-up or longer (4). However, many trials in the previous review used multicontact interventions, in contrast to the modal single-episode, computer-delivered interventions in the present review. Our findings for direction and magnitude of change in weekly alcohol consumption are similar to those of a previous e-intervention review of PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and EMBASE in May 2013 (17), which also found a reduction in consumption of approximately 1 drink per week at 6-month follow-up or longer, with no clinically or statistically significant effect at 12 months or longer (17). Another review of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, CINAHL, PubMed, and EMBASE in September 2013 found no statistically significant effect of e-intervention on alcohol consumption at 6 months or longer (13).

The interventions discussed here may have successfully accomplished the desired aim of achieving small reductions in alcohol consumption with very little investment of clinical time. However, further research is needed to more confidently determine whether e-interventions can produce longer-term benefits and influence other clinically significant outcomes. If e-interventions are not designed to be robust enough to produce enduring benefits on other clinically significant outcomes, such as meeting drinking limits and improving physical health, then interventions that can improve these outcomes are needed. Although variability in treatment intensity was not sufficient to evaluate its effect on alcohol-related outcomes, exploratory qualitative analyses suggest that more intensive interventions with higher-level supplementary human support (such as phone counseling) could improve engagement and effectiveness. Although brief e-interventions could be a cost-effective way to effect small reductions in alcohol consumption in many persons, it is worth considering the value of developing more intensive e-interventions. Such interventions could include cognitive behavioral coping strategies and exercises tailored to the individual, who would then have access to e-interventions for daily skill building and coping with high-risk situations. This could yield greater improvement (14) without much of an increase in financial investment or clinician time. Because the primary cost of e-intervention is in development, once an intensive intervention is developed it could be delivered at a similar low cost to the existing brief interventions.

E-interventions for alcohol misuse continue to be an area of interest. A search of ClinicalTrials.gov for e-intervention trials of alcohol misuse that would likely meet the review criteria for our review when completed found 17 ongoing trials, including 3 with mobile applications. As future e-intervention trials are being designed, they should complement measures of consumption with more measures of clinically relevant outcomes, such as drinking within recommended limits, which has the most established relationship with health outcomes (59). The number of weeks of drinking within limits would be also be a useful outcome variable for determining trial sample size. More data on episodes of binge drinking, alcohol-related health markers, social or legal impairment, and health-related quality of life are needed. Ideally, e-interventions for alcohol misuse will be developed with the aim of addressing not only hazardous use but also AUDs, because e-interventions can provide frequent support over time to prevent relapse. Alcohol consumption levels and patterns could be used to determine which treatment components and goals (for example, moderation vs. abstinence) are appropriate for the patient. For AUDs, intensive e-intervention combined with a degree of human counseling, either by e-mail or phone, will likely be necessary to produce effective results. Future research could use mobile health technology to improve engagement with the treatment; some early promising results have already been seen (32). Use of corroborating evidence of abstinence or moderate alcohol use that does not rely on self-report, such as transdermal alcohol monitoring (60), would address recall bias and demand characteristics in e-intervention research.

The most common study limitations that increased risk of bias were lack of participant blinding to study condition, which is difficult in a behavioral trial, and incomplete or perceived potential for selective reporting of outcome data (Appendix Table 4, available at www.annals.org), suggesting the possibility of inflation of estimated effects due to selective reporting of statistically significant differences in favor of e-interventions. The literature is also limited by a dearth of trials and lack of variability in e-intervention subtypes to conduct analyses to determine which intervention components and features are most effective. This review included several analyses with moderate to high heterogeneity, which seemed to be heavily influenced by inclusion of more intensive treatments that involved more interaction with e-interventions, interactive voice response, human support, or some combination of these treatment components. Previous research found that assessment itself was associated with decreased alcohol consumption, which potentially obscured e-intervention effects. These limitations constrained our evaluation of factors that contributed to variable treatment effects.

E-interventions generally reduced alcohol consumption, but effects were small (approximately 1 drink less per week) and no effect was maintained to 12 months. More clinically significant measures, such as meeting drinking limit guidelines, need to be measured in clinical trials and targeted by e-interventions. More intensive interventions with extended interaction between the person and the e-intervention and possibly human support could produce more robust, enduring benefits with the possibility of improved health and decreased alcohol-related impairment.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Avishek Nagi, MS, for organizational support and Rebecca Gray, DPhil, for editorial assistance.

Grant Support: This article is based on research conducted by the Evidence-based Synthesis Program Center at the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, funded by the Health Services Research & Development, Office of Research & Development, Veterans Health Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (Evidence-based Synthesis Program Project #09-009). Dr. Dedert was supported by the Clinical Sciences Research & Development Service of the Veterans Affairs Office of Research & Development (award no. 1IK2CX000718).

Appendix: Criteria Used in Quality Assessment of RCTs

General Instructions

Rate each risk of bias item listed below as Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk (see Cochrane guidance to inform judgements). Add comments to justify ratings. After considering each of the quality items, give the study an overall rating of “Low risk,” “Moderate risk,” or “High risk” (see below).

Rating of individual items:

- Selection bias:

- *Randomization adequate (Adequate methods include: random number table, computer-generated randomization, minimization w/o a random element) Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

- *Allocation concealment (Adequate methods include: pharmacy-controlled randomization, numbered sealed envelopes, central allocation) Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

- Baseline characteristics (Consider whether there were systematic differences observed in baseline characteristics and prognostic factors between groups, and if important differences were observed, if the analyses controlled for these differences) Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

- Performance bias:

- *Concurrent interventions or unintended exposures: (Consider concurrent intervention or an unintended exposure [eg, crossovers; contamination – some control group gets the intervention] that might bias results) Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

- Protocol variation: (Consider whether variation from the protocol compromised the conclusions of the study) Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

- Detection bias:

- *Subjects Blinded?: (Consider measures used to blind subjects to treatment assignment and any data presented on effectiveness of these measures) Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

- *Outcome assessors blinded (hard outcomes): (Outcome assessors blind to treatment assignment for “hard outcomes” such as mortality) Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

- *Outcome assessors blinded (soft outcomes): (Outcome assessors blind to treatment assignment for “soft outcomes” such as symptoms) Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

- Measurement bias: (Reliability and validity of measures used) Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

- Attrition bias:

- *Incomplete outcome data: (Consider whether incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed, including: systematic differences in attrition between groups [differential attrition]; overall loss to follow-up [overall attrition]; and whether an “intention-to-treat” [ITT; all eligible patients that were randomized are included in analysis] analysis was performed) (Note – mixed models and survival analyses are in general ITT) Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

-

Reporting bias:

- *Selective outcomes reporting: (Consider whether there is any suggestion of selective outcome reporting (e.g., systematic differences between planned and reported findings)? Low risk/High risk/Unclear risk

*Items contained in Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool

Overall study rating:

Please assign each study an overall quality rating of “Low risk,” “High risk,” or “Unclear risk” based on the following definitions:

A “Low risk” study has the least bias, and results are considered valid. A low risk study uses a valid approach to allocate patients to alternative treatments; has a low dropout rate; and uses appropriate means to prevent bias, measure outcomes, and analyze and report results. [Items 1a and 1c; 2a; 3b and 3c; and 4a are all rated low risk]

A “Moderate risk” study is susceptible to some bias but probably not enough to invalidate the results. The study may be missing information, making it difficult to assess limitations and potential problems (unclear risk). As the moderate risk category is broad, studies with this rating vary in their strengths and weaknesses. [Most, but not all of the following items are rated low risk: Items 1a and 1c; 2a; 3b and 3c; and 4a]

A “High risk” rating indicates significant bias that may invalidate the results. These studies have serious errors in design, analysis, or reporting; have large amounts of missing information; or have discrepancies in reporting. The results of a high risk study are at least as likely to reflect flaws in the study design as to indicate true differences between the compared interventions. [At least one-half of the individual quality items are rated high risk or unclear risk]

Conflict of interest: (Record but not used as part of Risk of Bias Assessment)

Was there the absence of potential important conflict of interest?: The focus here is financial conflict of interest. If no financial conflict of interest (eg, if funded by government or foundation and authors do not have financial relationships with drug/device manufacturer), then answer “Yes.” Yes/No/Unclear

Appendix Figure 1.

Summary of evidence search and selection. AUD = alcohol use disorder; RCT = randomized, controlled trial. * Manuscript reference list includes additional references cited for background and methods. All 28 trials and 3 trials of AUD were qualitatively described, and quantitative meta-analysis was done for 25 trials.

Appendix Figure 2.

Alcohol reduction to meet drinking limit guidelines at 6 mo in studies of adults. NR = not reported. * Did not report event rates. Intervention effects are based on adjusted estimates reported from a logistic regression model.

Appendix Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Study, Year (Reference); Population Type; Participants Randomly Assigned*; Treatment Groups | Intervention Type | Control Type | Mean Age (SD); Percentage Female; Percentage White | Location; Setting; VA† | Education, by Category or Mean Years (SD) | Mean Baseline Alcohol Intake, g/wk | Baseline Alcohol Instrument Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bischof et al, 2008 (33) Adult 408 3 |

E-intervention + phone (full) E-intervention + phone (stepped) |

WL | 36.5 (13.5) 32 NR |

Europe NR No |

Mean years (SD): E-intervention (full): 10.3 (2.7) E-intervention (stepped): 10.4 (2.7) WL: 10.4 (2.1) |

253.90 | NR |

| Boon et al, 2011 (57) Adult 450 2 |

E-intervention | IC | 40.5 (15.2) 0 NR |

Europe Web access No |

E-intervention: Less than college: 46.1% College or higher: 53.9% IC: Less than college: 47.7% College or higher: 52.3% |

312.91 | NR |

| Brendryen et al, 2014 (36) Adult 244 2 |

E-intervention | IC | 38.0 (13.5) 41.5 NR |

Europe Web access No |

NR | 235.2 | FAST 6.3 (2.9) |

| Collins et al, 2014 (54) Students 724 3 |

E-intervention (PNF) E-intervention (DB) |

WL | 20.8 (1.4) 56 67 |

United States University No |

Total population: Some college or higher: 100% |

439.0 | RAPI (other ETOH-related problems) E-intervention (PNF): 5.6 (7.0) E-intervention (DB): 5.8 (7.5) AO: 5.0 (5.3) |

| Cucciare et al, 2013 (47) Adults 167 2 |

E-intervention | TAU | 59.3 (15.0) 12 69 |

United States Clinic Yes |

NR | 336.11 | AUDIT-C Overall: 6.4 (2.50) E-intervention: 6.3 (2.5) TAU: 6.5 (2.5) |

| Cunningham et al, 2009 (45) Adults 185 2 |

E-intervention | IC | 40.20 (13.45) 47 NR |

Canada NR No |

E-intervention: College or higher: 78.3% IC: College or higher: 77.4% |

180.52 | AUDIT-C Overall: 6.7 (2.10) E-intervention: 7.0 (2.1) IC: 6.4 (2.1) |

| Gustafson et al, 2014 (32) Adults 349 2 |

E-intervention + TAU | TAU | 38.0 (10.0) 39.3 80.2 |

United States Smartphone No |

Total population: Less than college: 92.0% College or higher: 8.0% |

NR | NR |

| Hansen et al, 2012 (46) Adults 1380 3 |

E-intervention (PNF) E-intervention (personalized brief advice) |

WL | 44-65 (range) 45 NR |

Europe Web access No |

Total population: ≥15 y of education: 51.7% |

271.87 | NR |

| Hasin et al, 2013 (34) Adults 258 3 |

MI + IVR | IC | 45.70 (8.10) 22 None (100% African American) |

United States NR (primary diagnosis is HIV) No |

NR | NR | NR |

| Hester et al, 2012 (56) Students 144 2 |

E-intervention | TAU | 20.40 (2.0) 38 57 |

United States University clinic No |

Total population: College or higher: 100% |

290.75 | NR |

| Kypri et al, 2009 (38) Students 2435 2 |

E-intervention | WL | 19.70 (2.0) 45 NR |

New Zealand Web access No |

E-intervention: College or higher: 100% WL: College or higher: 100% |

85.00 | Instrument NR Overall: 14.2 (5.10) E-intervention: 14.2 (5.1) WL: 14.3 (5.1) |

| Kypri et al, 2008 (39) Students 429 2 |

E-intervention | IC | 20.1 (2.00) 52 NR |

New Zealand NR No |

E-intervention: College or higher: 100% IC: College or higher: 100% |

NR | AUDIT Overall: 14.9 (5.10) E-intervention: 14.9 (5.1) IC: 15.1 (5.5) |

| Kypri et al, 2004 (48) Students 104 2 |

E-intervention | IC | 20.20 (1.62) NR NR |

New Zealand University clinic No |

E-intervention: College or higher: 100% IC: College or higher: 100% |

NR | AUDIT Overall: 16.6 (5.85) E-intervention: 16.6 (5.7) IC: 16.6 (6.0) |

| LaBrie et al, 2013 (51) Students 1110 3 |

E-intervention-BASICS E-intervention PNF |

AC | 19.9 (1.3) 56.7 75.7 |

United States University No |

Total population: Some college or higher: 100% |

149.6 | RAPI E-intervention BASICS: 4.4 (5.8) E-intervention PNF: 3.85 (NR) Control: 3.3 (3.4) |

| Lewis et al, 2014 (55) Students 480 3 |

E-intervention ETOH E-intervention ETOH + RSB |

AC | 20.08 (1.48) 57.6 70 |

United States Web access No |

Total population: Some college or higher: 100% |

183.12 | BYAACQ E-intervention ETOH: 7.65 (4.73) E-intervention ETOH + RSB: 8.49 (5.34) AC: 8.26 (5.49) |

| Monahan et al, 2013 (49) Students 133 3 |

E-intervention (e-CHUG) | MI (BASICS) WL |

18-26 (range) 50 65.4 |

United States University research lab No |

Total population: College or higher: 100% |

205.18 | NR |

| Moreira et al, 2012 (58) Students 1751 2 |

E-intervention | WL | 17-19: 59.6% 20-24: 34.3% ≥25: 6.1% Or <25: 93.7% 62 NR |

Europe NR No |

Total population: College or higher: 100% |

140.61 | AUDIT Overall: 11.10 (7.01) E-intervention: 11.25 (7.15) WL: 11 (6.86) |

| Mundt et al, 2006 (35) Adults 60 3 |

IVR IVR + follow-up For relapse prevention |

WL | 41.9 (9.20) 45 95 |

United States NR (IVR) No |

NR | NA (relapse prevention) | NR |

| Neighbors et al, 2010 (37) Students 491 3 |

E-intervention (GSF) E-intervention (multidose GSF) |

AC | 18.2 (0.60) 57.6 65.3 |

United States NR No |

Total population: College or higher: 100% |

159.12 | NR |

| Neighbors et al, 2004 (50) Students 252 2 |

E-intervention | WL | 18.50 (1.2) 59 79.5 |

United States University No |

Total population: College or higher: 100% |

161.35 | ACI Overall: 1.95 (1.35) E-intervention: 2.03 (1.35) WL: 1.86 (1.35) |

| Neumann et al, 2006 (43) Adults 1136 2 |

E-intervention | WL | Median (range): 30.5 (24–29) 21 NR |

Europe Clinic No |

NR | 188.91 | Median AUDIT (IQR) E-intervention: 7 (6–11) WL: 8 (6–11) |

| Riper et al, 2008 (44) Adults 261 2 |

E-intervention | IC | 46.1 (9.1) 49 NR |

Europe NR No |

E-intervention: Less than college: 31.5% College or higher: 68.5% IC: Less than college: 29% College or higher: 71% |

436.00 | NR |

| Schulz et al, 2013 (40) Adults 448 2 |

E-intervention | WL | 41.72 (NR) 43.5 NR |

Europe Web access No |

Total population: College or higher: 34% |

129.4 | AUDIT ≥8 Overall: 80% |

| Sinadinovic et al, 2012 (41) Adults 202 2 |

E-intervention | TAU | 32.5 (NR) 45 NR |

Europe NR Dual diagnosis: ETOH + drug No |

NR | NR | AUDIT-C Overall: 7.60 (2.85) E-intervention: 7.8 (2.7) TAU: 7.3 (3.0) |

| Voogt et al, 2013 (52) Students 913 2 |

E-intervention | WL | 20.9 (1.70) 40 NR |

Europe NR No |

Total population: College or higher: 100% |

218.01 | NR |

| Voogt et al, 2014 (61) Students 907 2 |

E-intervention | WL | 20.85 (1.70) 40 NR |

Europe University No |

Total population: Some college or higher: 100% |

310.1 | NR |

| Wallace et al, 2011 (42) Adults 2652 2 |

E-intervention | IC | 38.0 (11.0) 57 NR |

Europe NR No |

E-intervention: College or higher: 52% IC: College or higher: 51% |

368.00 | AUDIT-C Overall: 8.5 (2.02) |

| Walters et al, 2009 (53) Students 279 4 |

E-intervention (Web FB only) | MI MI + FB WL |

19.80 (NR) 64.2 84.6 |

United States University No |

Total population: College or higher: 100% |

206.95 | RAPI Overall: 6.35 (6.45) E-intervention: 5.99 (6.01) MI: 6.37 (6.50) MI + FB: 6.67 (6.92) WL: 6.38 (6.35) |

AC = attention control; ACI = Alcohol Consumption Inventory; AO = assessment-only control; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption; BASICS = Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students; BYAACQ = Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire; DB = decisional balance; e-CHUG = Electronic Check-up to Go; e-intervention = electronic intervention; ETOH = alcohol; FAST = Fast Alcohol Screening Test; FB = feedback; GSF = gender-specific feedback; IC = information control; IQR = interquartile range; IVR = interactive voice response; MI = motivational interviewing; NA = not applicable; NR = not reported; PNF = personalized normative feedback; RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index; RSB = risky sexual behavior; TAU = treatment as usual; VA = Veterans Administration; WL = wait list.

Number of participants randomly assigned in the groups analyzed for this report.

Yes or no.

Appendix Table 2.

Search Strategies

| Set | Search |

|---|---|

|

Database: PubMed; search date: 18 August 2014; updated: 25 March 2015

| |

| 1 | “Behavior Therapy”[Mesh:NoExp] OR ((behavior[tiab] OR behaviour[tiab]) AND (therapy [tiab] OR therapies[tiab])) OR “Cognitive Therapy”[Mesh] OR ((cognitive[tiab] OR cognition[tiab]) AND (therapy[tiab] OR therapies[tiab])) OR “Psychotherapy, Brief”[Mesh] OR ((brief[tiab] OR short-term[tiab]) AND (psychotherapy[tiab] OR psychotherapies[tiab])) OR “brief counseling”[tiab] OR intervention[tiab] OR interventions[tiab] OR “Health Education”[Mesh] |

|

| |

| 2 | “Alcoholism”[Mesh] OR “Alcohol Drinking”[Mesh] OR ((heavy[tiab] OR hazardous[tiab] OR harmful[tiab] OR excessive[tiab] OR problem[tiab] OR binge[tiab] OR controlled[tiab] OR risky[tiab] OR “at risk”[tiab] OR “at-risk”[tiab] OR use[tiab]) AND drink*[tiab] AND (Alcohol[tiab] OR “Alcoholic Beverages”[Mesh])) |

|

| |

| 3 | “Therapy, Computer-Assisted”[Mesh] OR “Internet”[Mesh] OR “Cellular Phone”[Mesh] OR “Computers”[Mesh] OR “Computer-assisted”[tiab] OR computerized[tiab] OR “low intensity”[tiab] OR internet[tiab] OR web[tiab] OR “social media”[tiab] OR online[tiab] OR computer[tiab] OR computers[tiab] OR electronic[tiab] OR mobile[tiab] OR smartphone[tiab] OR smartphones[tiab] OR tablet[tiab] OR tablets[tiab] OR self-paced[tiab] OR “health buddy”[tiab] OR e-health[tiab] OR ehealth[tiab] OR m-health [tiab] OR mhealth[tiab] |

|

| |

| 4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

|

| |

| 5 | ((randomized controlled trial[pt] OR controlled clinical trial[pt] OR randomized[tiab] OR randomised[tiab] OR randomization[tiab] OR randomisation[tiab] OR placebo[tiab] OR drug therapy[sh] OR randomly[tiab] OR trial[tiab] OR groups[tiab]) NOT (animals[mh] NOT humans[mh]) NOT (Editorial[ptyp] OR Letter[ptyp] OR Case Reports[ptyp] OR Comment[ptyp])) |

|

| |

| 6 | #4 AND #5; limit to English, 2000 – present |

|

Database: EMBASE; search date: 18 August 2014

| |

| 1 | ‘cognitive therapy’/exp OR ‘behavior therapy’/exp OR ‘behavior modification’/exp OR ‘health education’/exp OR ((‘psychotherapy’/exp OR psychotherapy:ab,ti OR psychotherapies:ab,ti) AND (brief:ab,ti OR ‘short term’:ab,ti)) OR ((behavior:ab,ti OR behaviour:ab,ti) AND (therapy:ab,ti OR therapies:ab,ti)) OR ((cognitive:ab,ti OR cognition:ab,ti) AND (therapy:ab,ti OR therapies:ab,ti)) OR ‘brief counseling’:ab,ti OR intervention:ab,ti OR interventions:ab,ti |

|

| |

| 2 | ‘alcoholism’/exp OR ‘drinking behavior’/exp OR ((heavy:ab,ti OR hazardous:ab,ti OR harmful:ab,ti OR excessive:ab,ti OR problem:ab,ti OR binge:ab,ti OR controlled:ab,ti OR risky:ab,ti OR “at risk”:ab,ti OR “at-risk”:ab,ti OR use:ab,ti) AND drink*:ab,ti AND (Alcohol:ab,ti OR ‘alcoholic beverage’/exp)) |

|

| |

| 3 | ‘computer assisted therapy’/exp OR ‘mobile phone’/exp OR ‘Internet’/exp OR ‘computer’/exp OR ‘Computer assisted’:ab,ti OR computerized:ab,ti OR ‘low intensity’:ab,ti OR internet:ab,ti OR web:ab,ti OR “social media”:ab,ti OR online:ab,ti OR computer:ab,ti OR computers:ab,ti OR electronic:ab,ti OR mobile:ab,ti OR smartphone:ab,ti OR smartphones:ab,ti OR tablet:ab,ti OR tablets:ab,ti OR self-paced:ab,ti OR ‘health buddy’:ab,ti OR e-health:ab,ti OR ehealth:ab,ti OR m-health:ab,ti OR mhealth:ab,ti |

|

| |

| 4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

|

| |

| 5 | (‘randomized controlled trial’/exp OR ‘crossover procedure’/exp OR ‘double blind procedure’/exp OR ‘single blind procedure’/exp OR random*:ab,ti OR factorial*:ab,ti OR crossover*:ab,ti OR (cross NEAR/1 over*):ab,ti OR placebo*:ab,ti OR (doubl* NEAR/1 blind*):ab,ti OR (singl* NEAR/1 blind*):ab,ti OR assign*:ab,ti OR allocat*:ab,ti OR volunteer*:ab,ti) NOT (‘case report’/exp OR ‘case study’/exp OR ‘editorial’/exp OR ‘letter’/exp OR ‘note’/exp) |

|

| |

| 6 | #4 AND #5 |

|

| |

| 7 | #6 AND [embase]/lim NOT [medline]/lim |

|

| |

| 8 | #7, 2000 – present, English |

|

Database: PsycINFO; search date: 18 August 2014

| |

| 1 | ((DE “Behavior Therapy”) OR (DE “Cognitive Behavior Therapy”)) OR (DE “Cognitive Therapy”) OR (DE “Brief Psychotherapy”) OR (DE “Health Education”) OR TI (((behavior OR behaviour) AND (therapy OR therapies[tiab)) OR ((cognitive OR cognition) AND (therapy OR therapies)) OR ((brief OR short-term) AND (psychotherapy OR psychotherapies)) OR “brief counseling” OR intervention OR interventions) OR AB (((behavior OR behaviour) AND (therapy OR therapies[tiab)) OR ((cognitive OR cognition) AND (therapy OR therapies)) OR ((brief OR short-term) AND (psychotherapy OR psychotherapies)) OR “brief counseling” OR intervention OR interventions) |

|

| |

| 2 | (DE “Alcoholism”) OR (DE “Alcohol Drinking Patterns” OR DE “Alcohol Abuse” OR DE “Alcohol Intoxication” OR DE “Social Drinking”) OR ((TI (heavy OR hazardous OR harmful OR excessive OR problem OR binge OR controlled OR risky OR “at risk” OR “at-risk” OR use) OR AB (heavy OR hazardous OR harmful OR excessive OR problem OR binge OR controlled OR risky OR “at risk” OR “at-risk” OR use)) AND (TI (drink*) OR AB (drink*)) AND (TI Alcohol OR AB Alcohol OR (DE “Alcoholic Beverages”))) |

|

| |

| 3 | (((DE “Computer Assisted Therapy”) OR (DE “Internet”)) OR (DE “Cellular Phones”)) OR (DE “Computers” OR DE “Analog Computers” OR DE “Computer Games” OR DE “Digital Computers” OR DE “Microcomputers”) OR TI (“Computer-assisted” OR computerized OR “low intensity” OR internet OR web OR “social media” OR online OR computer OR computers OR electronic OR mobile OR smartphone OR smartphones OR tablet OR tablets OR self-paced OR “health buddy” OR e-health OR ehealth OR m-health OR mhealth) OR AB (“Computer-assisted” OR computerized OR “low intensity” OR internet OR web OR “social media” OR online OR computer OR computers OR electronic OR mobile OR smartphone OR smartphones OR tablet OR tablets OR self-paced OR “health buddy” OR e-health OR ehealth OR m-health OR mhealth) |

|

| |

| 4 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 |

|

| |

| 5 | #4 AND #5; Limiters – Publication Year: 2000-; English; Methodology: TREATMENT OUTCOME/CLINICAL TRIAL |

|

| |

| Database: Cochrane Library; search date: 18 August 2014 | |

| 1 | MeSH descriptor: [Behavior Therapy] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Cognitive Therapy] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Psychotherapy, Brief] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Health Education] explode all trees OR ((behavior:ab,ti OR behaviour:ab,ti) AND (therapy :ab,ti OR therapies:ab,ti)) OR ((cognitive:ab,ti OR cognition:ab,ti) AND (therapy:ab,ti OR therapies:ab,ti)) OR ((brief:ab,ti OR short-term:ab,ti) AND (psychotherapy:ab,ti OR psychotherapies:ab,ti)) OR “brief counseling”:ab,ti OR intervention:ab,ti OR interventions:ab,ti |

|

| |

| 2 | MeSH descriptor: [Alcoholism] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Alcohol Drinking] explode all trees OR ((heavy:ab,ti OR hazardous:ab,ti OR harmful:ab,ti OR excessive:ab,ti OR problem:ab,ti OR binge:ab,ti OR controlled:ab,ti OR risky:ab,ti OR “at risk”:ab,ti OR “at-risk”:ab,ti OR use:ab,ti) AND drink*:ab,ti AND (Alcohol:ab,ti OR MeSH descriptor: [Alcoholic Beverages] explode all trees |

|

| |

| 3 | MeSH descriptor: [Therapy, Computer-Assisted] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Internet] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Cellular Phone] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Computers] explode all trees OR “Computer-assisted”:ab,ti OR computerized:ab,ti OR “low intensity”:ab,ti OR internet:ab,ti OR web:ab,ti OR “social media”:ab,ti OR online:ab,ti OR computer:ab,ti OR computers:ab,ti OR electronic:ab,ti OR mobile:ab,ti OR smartphone:ab,ti OR smartphones:ab,ti OR tablet:ab,ti OR tablets:ab,ti OR self-paced:ab,ti OR “health buddy”:ab,ti OR e-health:ab,ti OR ehealth:ab,ti OR m-health :ab,ti OR mhealth:ab,ti |

|

| |

| 4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 (not limited by date) |

Appendix Table 3.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Study Characteristic | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults aged ≥18 y with alcohol misuse (e.g., positive alcohol screen; KQ 2), at high risk for AUD, or with diagnosis of AUD (KQ 3). | Pregnant women |

| Intervention | Intervention must be a computer-based therapy adhering to evidence-based treatment principles and providing individually delivered treatment for alcohol misuse delivered by CD-ROM, Web-based, IVR, mobile phones, or in-home electronic devices (e.g., Health Buddy [Bosch Healthcare]) and may be combined with various levels of supplementary human support. | Interventions targeted at dyads (e.g., couple) or primary prevention Computerized screening only |

| Comparator | The comparator for KQ 2 and KQ 3 was usual care not involving psychotherapy, WL, or information or attention control. For KQ 4, the comparator was face-to-face treatment. | Any comparator where the effect of the electronic aspect of the intervention could not be isolated |

| Outcome | Studies must report effects on at least 1 of the following relevant outcomes: alcohol consumption, alcohol-related health problems, alcohol-related legal or social problems, HRQOL, functional status measures, medical utilization, or adverse effects from treatment. | – |

| Timing | Outcomes reported at ≥6 mo from randomization and initiation of intervention. | Outcomes reported at <6 mo |

| Setting | Outpatients in any setting (general medical, emergency department, and community) or participants not engaged in clinical care who are enrolled through self-assessments. We included studies where enrollment was inpatient but the majority of the intervention was delivered outpatient. | Inpatient settings for intervention delivery |

| Study design | RCTs with ≥50 participants. The sample size requirement is designed to exclude small pilot studies that typically are underpowered and have more methodological problems than larger trials. Studies with small samples and no treatment effect are also less likely to be published, increasing the risk for publication bias. | RCTs with 50 participants |

| Publications | English-language publication Published from 2000 to present* Peer-reviewed, full publication Study conducted in North America, the European Union, or Australia/New Zealand† |

Non-English language Published before 2000 Abstract only |

AUD = alcohol use disorder; HRQOL = health-related quality of life; IVR = interactive voice response; KQ = key question; RCT = randomized, controlled trial; WL = wait list.

Rationale is that the Internet was developed in the 1990s and not used routinely for interventions until 2000. Based on our assessment of studies included in existing systematic reviews, the earliest relevant publication was in 2004.

Rationale is to include economically developed countries with sufficient similarities in health care system and culture to be applicable to U.S. medical care.

Appendix Table 4.

Quality of Included Studies

| Study, Year (Reference) | Individual Quality Assessment Criteria Ratings

|

Overall Rating | COI Absent? | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 1b | 1c | 2a | 2b | 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | 4 | 5 | |||

| Studies in adults | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Bischof et al, 2008 (33) | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | UNCL | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Boon et al, 2011 (57) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | UNCL | Low | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Brendryen et al, 2014 (36) | Low | Low | Low | High | High | High | UNCL | UNCL | Low | High | Low | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Cucciare et al, 2013 (47) | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | No |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Cunningham et al, 2009 (45) | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | UNCL | UNCL | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Gustafson et al, 2014 (32) | Low | UNCL | Low | UNCL | Low | High | NA | High | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Hansen et al, 2012 (46) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | UNCL | UNCL | UNCL | UNCL | UNCL | Low | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Hasin et al, 2013 (34) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Mundt et al, 2006 (35) | UNCL | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | High | UNCL | High | Low | UNCL | UNCL | High | No |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Neumann et al, 2006 (43) | UNCL | UNCL | Low | UNCL | Low | High | UNCL | UNCL | Low | High | UNCL | High | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Riper et al, 2008 (44) | UNCL | UNCL | Low | UNCL | High | High | UNCL | UNCL | Low | High | Low | High | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Schulz et al, 2013 (40) | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | High | NA | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Sinadinovic et al, 2012 (41) | UNCL | UNCL | High | UNCL | High | High | UNCL | UNCL | Low | High | Low | High | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Wallace et al, 2011 (42) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Moderate | Yes |

| Studies in college students | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Collins et al, 2014 (54) | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Moderate | UNCL |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Hester et al, 2012 (56) | UNCL | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | High | UNCL | UNCL | Low | UNCL | Low | High | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Kypri et al, 2009 (38) | Low | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Kypri et al, 2008 (39) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Kypri et al, 2004 (48) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| LaBrie et al, 2013 (51) | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | UNCL | Low | Moderate | UNCL |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Lewis et al, 2014 (55) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | UNCL |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Monahan et al, 2013 (49) | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | UNCL | UNCL | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Moreira et al, 2012 (58) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Neighbors et al, 2010 (37) | Low | Low | UNCL | UNCL | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Neighbors et al, 2004 (50) | UNCL | High | UNCL | Low | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Voogt et al, 2013 (52) | Low | UNCL | Low | UNCL | Low | Low | UNCL | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Voogt et al, 2014 (61) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | UNCL |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Walters et al, 2009 (53) | UNCL | UNCL | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Yes |

COI = conflict of interest; NA = not applicable; UNCL = unclear.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or Duke University. All work herein is original. All authors meet the criteria for authorship, including acceptance of responsibility for the scientific content of the manuscript.

Disclosures: Dr. Dedert reports other from the Health Services Research & Development, Office of Research & Development, Veterans Health Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and grants from Clinical Science Research & Development Service of the Veterans Affairs Office of Research & Development during the conduct of the study. Dr. McNiel reports other from the Health Services Research & Development, Office of Research & Development, Veterans Health Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and grants from Clinical Science Research & Development Service of the Veterans Affairs Office of Research & Development during the conduct of the study. Dr. Williams reports grants from the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development during the conduct of the study. Authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M15-0285.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: E.A. Dedert, J.R. McDuffie, R. Stein, J.M. McNiel, J.W. Williams.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: R. Stein, J.M. McNiel, A.S. Kosinski, C.E. Freiermuth, A. Hemminger, J.W. Williams.

Drafting of the article: E.A. Dedert, J.R. McDuffie, R. Stein, C.E. Freiermuth.

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: J.R. McDuffie, R. Stein, J.M. McNiel, J.W. Williams.

Final approval of the article: E.A. Dedert, J.R. McDuffie, A.S. Kosinski, C.E. Freiermuth, J.W. Williams.

Statistical expertise: A.S. Kosinski, J.W. Williams.

Obtaining of funding: J.W. Williams.

Collection and assembly of data: J.R. McDuffie, R. Stein, J.M. McNiel, A. Hemminger, J.W. Williams.

References

- 1.McBride O, Adamson G, Bunting BP, McCann S. Characteristics of DSM-IV alcohol diagnostic orphans: drinking patterns, physical illness, and negative life events. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:272–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:554–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moyer VA, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:210–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR, Brown JM, Brownley KA, Council CL, et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:645–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking Levels Defined. Accessed at www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking on 22 April 2015.

- 6.Barry KL, Blow FC, Willenbring ML, McCormick R, Brockmann LM, Visnic S. Use of alcohol screening and brief interventions in primary care settings: implementation and barriers. Subst Abus. 2004;25:27–36. doi: 10.1300/J465v25n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsen P. Brief alcohol intervention—where to from here? Challenges remain for research and practice. Addiction. 2010;105:954–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams EC, Johnson ML, Lapham GT, Caldeiro RM, Chew L, Fletcher GS, et al. Strategies to implement alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care settings: a structured literature review. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:206–14. doi: 10.1037/a0022102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson JM, Fayter D, Mdege N, Stirk L, Sowden AJ, Godfrey C. Interventions for alcohol and drug problems in outpatient settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32:356–67. doi: 10.1111/dar.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pew Research Center. Health Fact Sheet. Accessed at www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/health-fact-sheet on 22 April 2015.

- 11.Cunningham JA, Selby PL, Kypri K, Humphreys KN. Access to the Internet among drinkers, smokers and illicit drug users: is it a barrier to the provision of interventions on the World Wide Web? Med Inform Internet Med. 2006;31:53–8. doi: 10.1080/14639230600562816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vernon ML. A review of computer-based alcohol problem services designed for the general public. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:203–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riper H, Blankers M, Hadiwijaya H, Cunningham J, Clarke S, Wiers R, et al. Effectiveness of guided and unguided low-intensity internet interventions for adult alcohol misuse: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riper H, Spek V, Boon B, Conijn B, Kramer J, Martin-Abello K, et al. Effectiveness of E-self-help interventions for curbing adult problem drinking: a meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e42. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rooke S, Thorsteinsson E, Karpin A, Copeland J, Allsop D. Computer-delivered interventions for alcohol and tobacco use: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2010;105:1381–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Hewitt C, Hartley S, Godfrey C. Can stand-alone computer-based interventions reduce alcohol consumption? A systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106:267–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donoghue K, Patton R, Phillips T, Deluca P, Drummond C. The effectiveness of electronic screening and brief intervention for reducing levels of alcohol consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e142. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:719–59. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slutske WS. Alcohol use disorders among U.S. college students and their non-college-attending peers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:321–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dedert E, Williams JW, Stein R, McNeil JM, McDuffie J, Ross I, et al. e-Interventions for Alcohol Misuse. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014. Accessed at www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/alcohol_misuse.cfm on 22 April 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bewick BM, Trusler K, Barkham M, Hill AJ, Cahill J, Mulhern B. The effectiveness of web-based interventions designed to decrease alcohol consumption—a systematic review. Prev Med. 2008;47:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Elliott JC, Bolles JR, Carey MP. Computer-delivered interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2009;104:1807–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Elliott JC, Garey L, Carey MP. Face-to-face versus computer-delivered alcohol interventions for college drinkers: a meta-analytic review, 1998 to 2010. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elliott JC, Carey KB, Bolles JR. Computer-based interventions for college drinking: a qualitative review. Addict Behav. 2008;33:994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White A, Kavanagh D, Stallman H, Klein B, Kay-Lambkin F, Proudfoot J, et al. Online alcohol interventions: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e62. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Accessed at www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/search-for-guides-reviews-and-reports/?pageaction=displayproduct&productid=318 on 22 April 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Software. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knapp G, Hartung J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat Med. 2003;22:2693–710. doi: 10.1002/sim.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu R, Gartlehner G, Grant M, Shamliyan T, Sedrakyan A, Wilt TJ, et al. Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1187–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih MY, Atwood AK, Johnson RA, Boyle MG, et al. A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:566–72. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bischof G, Grothues JM, Reinhardt S, Meyer C, John U, Rumpf HJ. Evaluation of a telephone-based stepped care intervention for alcohol-related disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]