Summary

The goal of this study was to analyse plasma procalcitonin (PCT) concentrations during infectious events of burns in ICU. We conducted a prospective, observational study in a 20-bed Burn Intensive Care Unit in Tunisia. A total of 121 patients admitted to the Burn ICU were included in our study. Serum PCT was measured over the entire course of stay in patients with predictive signs of sepsis according to the Americain Burn Association Criteria for the presence of infection. Patients were assigned to two groups depending on the clinical course and outcome: Group A = non septic patients; Group B = septic patients. A PCT cutoff value of 0,69 ng/ml for sepsis prediction was associated with the optimal combination of sensitivity (89%), specificity (85%), positive predictive value (82%) and negative predictive value (88%). Serum procalcitonin levels can be used as an early indicator of septic complication in patients with severe burn injuries as well as in monitoring the response to antimicrobial therapy.

Keywords: burns, sepsis, procalcitonin (PCT)

Abstract

Le but de cette étude était d’analyser la concentration de procalcitonine plasmatique (PCT) mesurée au cours des cas d’infection chez les patients brûlés en soins intensifs. Nous avons mené une étude observationnelle prospective dans une unité de soins intensifs de 20 lits en Tunisie. Un total de 121 patients admis ont été inclus dans notre étude. La PCT a été mesurée pendant toute la durée du séjour chez les patients avec des signes prédictifs de septicémie selon les critères de l’American Burn Association pour la présence de l’infection. Les patients ont été répartis en deux groupes en fonction de l’évolution clinique et les résultats: Groupe A = pas de patients septiques; Groupe B = patients septiques. Une valeur PCT de 0,69 ng/ml est associée à la combinaison optimale de sensibilité (89%), spécificité (85%), valeur prédictive positive (82%) et valeur prédictive négative (88%). Les niveaux de procalcitonine sérique peuvent être utilisés comme un indicateur précoce de complication septique chez les patients atteints de brûlures graves, ainsi que dans le contrôle de la réponse à la thérapie antimicrobienne.

Introduction

Sepsis is still the major cause of death in the late post traumatic period in patients with major burns. Early diagnosis of sepsis is crucial for the management and outcome of critically burned patients. Nevertheless signs of infection may be obscured by systemic dysfunction. Detection of sepsis would be expedited if a simple, inexpensive test could be performed routinely, with a high degree of accuracy in correctly differentiating sepsis from SIRS. Such an assay should improve the ability to identify severe infection, guide treatment and reduce the duration of antibiotic exposure. There are several helpful scores1,2 to diagnose sepsis but some of these are not appropriate for the burned patient. The routinely measured parameters, such as thrombocytes and leukocytes, are dependent upon the multiple operations performed on the burned patient (nutritional status, dehydration, skin grafting, sepsis, and so on). CRP, a good marker for infection because of its role in the acute phase response, is very sensitive and remains elevated in the severely burned patient over the whole ICU stay. Changes, whether an increase or decrease, are not always reliable.The use of biomarkers provides a novel approach to diagnosing infection, its severity and treatment response. Yet, due to chronic baseline inflammatory response3 and immune dysregulation,4 the traditional markers of acute infection are difficult to identify in the burn patient. In this study, we attempted to assess whether plasma procalcitonin (PCT) level was related to sepsis in burned patients.

Patients and methods

A prospective and observational study, approved by our Institutional Ethics Committee, was conducted in a 20- bed adult burn ICU at a university-affiliated teaching hospital in Tunis. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or next of kin. Participation did not modify the therapeutic strategy. All consecutive adult burn patients admitted within the first 48h post burn from April 1st to December 31st, 2008 were included in the study. Any patients with infections prior to the burn injury, or those who discharged or died within 48h after admission were ruled out of the study. Smoke inhlation was suspected based on the mechanism of burn and diagnosed by clinical examination as well as bronchoscopy. Resuscitation of these patients was undertaken according to the current standard of care. Parkland formula based on the burn size and body weight of the patient was applied as a first approximation of required fluid administration rates. Thereafter, fluid resuscitation was adapted in order to meet a target urine output of 0.5 to 1 ml/kg/h and a target mean arterial pressure > 65 mmHg. Early excision of deep partial and full thickness burns was done usually at day 2 or day 3 post burn injury by waterjet hydrosurgery (Versajet). Every day, all patients were evaluated to diagnosis signs of sepsis. Sepsis was defined according to the American Burn Association Criteria for the presence of infection:5

Body temperature >39°C or <36.5°C.

Heart rate >110 beats/min.

Respiratory rate >25/min.

Insulin resistance or feeding intolerance

Thrombocytopenia: platelets <100.000/mm3.

The presence of infection clinically or microbiologically documented: sepsis, urinary tract infection, lung, skin, etc.

Meeting more than 3 of these criteria should “trigger” concern for infection.

Blood samples from patients were drawn for measurement of serum procalcitonin (PCT) and routine tests including white blood cells (WCC) within the first 24h following admission and daily thereafter. Serum PCT levels were determined by immunoluminometric assay (Lumitest PCT, Brahms Diagnostica, Berlin, Germany). The normal serum value of PCT in a healthy individual without inflammation is less than 0.05 ng/mL.6 PCT levels associated with local infection, possible systemic infection, sepsis, or severe sepsis are: <0.5 ng/mL, 0.5-2 ng/mL, 2-10 ng/mL, and >10 ng/mL respectively.7

When an infectious process was suspected, blood cultures, burn wound samples, urinary tract samples and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) using fiberoptic bronchoscopy were performed if patients had criteria for pneumonia (fever, presence of new infiltrates on chest radiography, or purulent tracheal secretion). Empirical antibacterial therapy was started, after bacterial investigation, before the pathogen and its susceptibility pattern were known. The choice of antibacterial therapy was largely based on the presumed pathogens, whether the infection was acquired in the hospital or not, and on local surveillance data on aetiology and microbial resistance. Then, de-escalation therapy was guided by clinical and biological parameters, especially kinetics of PCT and also ensures patterns isolated and their susceptibility.

The patients were assigned to two groups: Group A (non septic patients) included patients with neither infection nor SIRS and patients with SIRS without infection, and Group B (septic patients) included patients with SIRS and episodes of infection (sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock), according to the ABA sepsis guidelines.5 Exploitation of data was performed using SPSS 16.0. For statistical analysis, we used the Chi-2 test or Fisher test when the conditions of validity of the Chi-2 test were not met. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the comparison of results. The different predictive values were studied with the area under the ROC curve. ÉcouterLire phonétiquementOptimum sensitivity, predictive value and area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve were evaluated.

Results

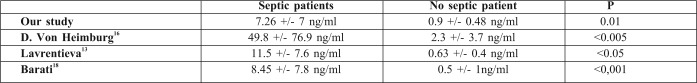

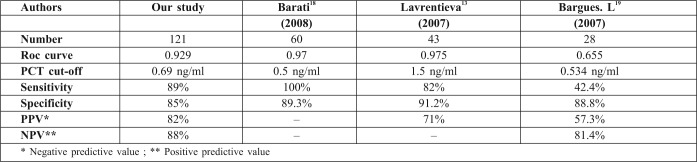

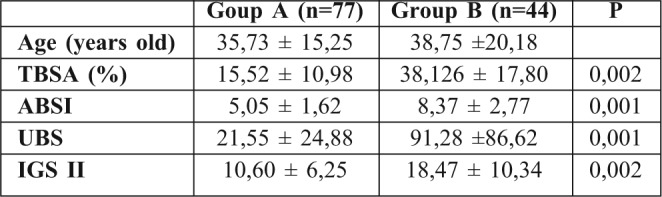

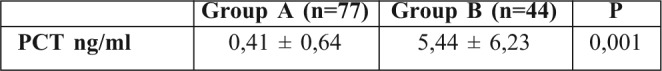

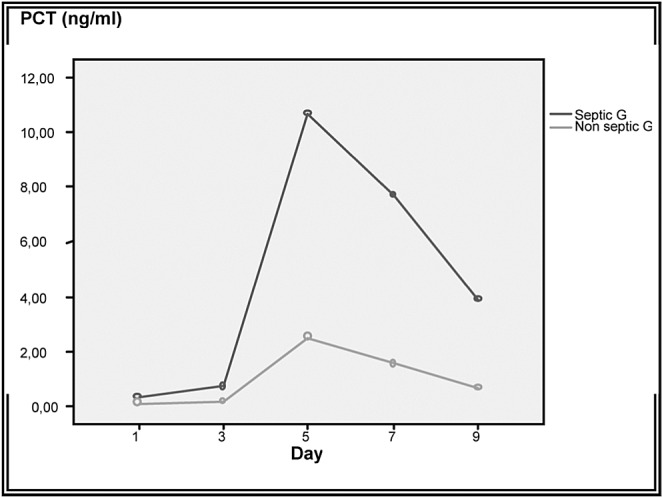

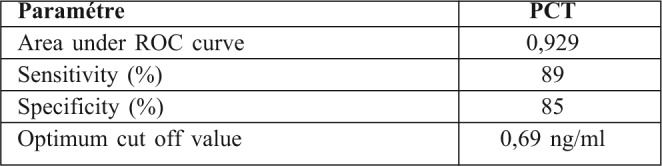

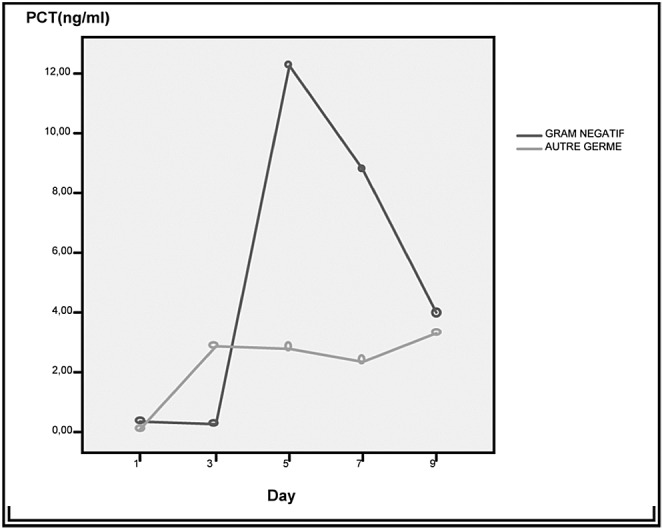

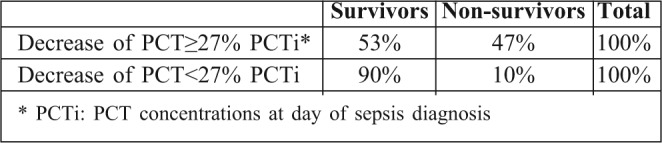

A total of 226 burn patients were admitted to our burn intensive care unit (ICU) during the 9-month study period and 121 were enrolled in the study. There were 105 patients excluded from the study: 37 of whom were discharged during the first 48 hours, 10 of whom died early in the first 3 days after admission because of severe and extensive burn injury (TBSA >80%), 40 of whom were secondary transfers and had sepsis before admission to our ICU, and 18 who refused to participate. Of the 121 patients in our study 77 were male and 44 female. The mean age was 37±17 years old. The average TBSA was 23±17 %. Patients were assigned into two groups: Group A (non septic, n=77) and Group B (septic, n=44). The results of a comparative study of the two groups are shown in Table I. Diagnosis of sepsis was performed in the first week of hospitalization in 90% of cases (mean: day 4). PCT was higher in patients with sepsis compared to those without sepsis (Table II). On day 5 post burn we found a strongly significant difference (p=0.001) between infected and non infected patients in terms of PCT serum concentrations, respectively 5,44 ± 6,23 ng/ml and 0,41 ± 0,64 ng/ml. There were significant differences in PCT levels between septic and non septic patients, and peak PCT-levels were higher in septic patients at day 5(day diagnosis sepsis) (Fig. 1). The area under the ROC curve was 0,929 on the day of sepsis diagnostic. A PCT cut-off value of 0,69 ng/ml was associated with the optimal combination of sensitivity (89%), specificity (85%), positive predictive value (82%) and negative predictive value (88%). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC curves) to distinguish presence or absence of sepsis were: 0.929 for PCT. The optimum cut-off value for PCT was 0.69 ng/ml with sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 85%, respectively (Table III). In the present study, among septic patients there was a prominent increase of the PCT level when gram-negative organisms (5,91± 6,48 ng/ml) were identified as opposed to gram positive (2,21 ± 2 ng/ml) (Fig. 2). Microorganisms associated with positive blood cultures are essentially staphylococcus aureus and pseudomonas aeruginosa. In survived septic patients, the PCT value, on day sepsis diagnosis, was significantly lower than the deceased septic patients respectively 1.6 ng/ml versus 21.43 ng/ml. There were significant differences in PCT levels throughout the course of the 2 Groups. PCT levels correlate closely with sepsis severity and can predict outcome (Fig. 3). In fact, PCT concentration ex119 ceeded 50 ng/ml in deceased septic patients. Decreased PCT concentrations of 27% between day of sepsis diagnosis and 3 days after empiric antimicrobial treatment have been detected as a predictive tool of favorable evolution during septic episodes (Table IV), with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC curve) of 0.812.

Table I. Comparative parameters between the two groups.

Table II. Markers of inflammation in the two groups.

Fig. 1. PCT-levels on admission and peak PCT-levels throughout the course in 2 groups.

Table III. Diagnosis performance in sepsis for PCT.

Fig. 2. PCT levels throughout the course in septic patients according to type of organisms.

Fig. 3. Time trend of PCT levels in survivors and non-survivors from sepsis.

Table IV. Assessment of prognostic value of PCT at day 3 after empiric antimicrobial treatment.

Discussion

Sepsis, clinically defined as the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) secondary to infection, is a common complication in Burn Intensive Care Units and delayed diagnosis is associated with increased morbidity, mortality and cost in the ICU. For these reasons, recognizing sepsis early is therefore of the utmost importance. Clinical and laboratory signs of systemic inflammation including changes in body temperature, leucocytosis and tachycardia are used for diagnosis of sepsis. However, they are neither specific nor sensitive for sepsis, and can be misleading because critically ill burn patients often manifest a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) without infection.8 This phenomenon might be in part responsible for withholding, delaying, or overutilizing antimicrobial treatment in critically ill burn patients.9 Thus, diagnosis of sepsis is frequently difficult. A marker that is able to distinguish inflammatory response to infection from other types of inflammation would be useful in clinical practice. The routinely measured parameters, such as white cell count (WCC), neutrophils, body temperature and CRP could help differentiate patients with either non-systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), non-infected SIRS, or infected SIRS. Changes, whether increase or decrease, are not always reliable. The ideal parameter for early sepsis diagnosis should be sensitive, specific, reliable and easy to measure. Procalcitonin shows some of these characteristics. While both procalcitonin site production and physiological role remain unclear, its interest has been evaluated in numerous studies including critically-ill patients with infection, shock, pancreatitis, major trauma, surgery and burns. PCT appeared to be a useful sepsis marker in heterogeneous population of adults in ICU.10,11 It increases earlier in patients with sepsis.12-15There was a significant increase of PCT serum concentration during episodes of sepsis in burned patients16-18 (Table V). In our study, PCT cut-off value for prediction of sepsis was 0,69ng/ml with a good sensitivity (89%) and specificity (85%).This result was found in other studies (Table VI). In many studies, PCT was proposed as a new marker of systemic inflammatory response to bacterial infection. Literature data seem to confirm that procalcitonin is a better marker of inflammation than C-reactive protein or cytokines, both as prognosis and diagnosis aid. Repeated measurements are more useful than single values.19Neely and al. compared PCT with CRP and platelet count in paediatric burns,18 and found that sensitivity and specificity of PCT for diagnosis of sepsis (defined as daily PCT increasement of 5 ng/ml or greater) were 42% and 67%, respectively. Procalcitonin correlates to the clinical outcome in sepsis. Zeni et al. found that PCT levels average 37 ng/ml (n=145) in severe sepsis [14], and Gramm and al. showed levels over 10 ng/ml (n=43).20 Our data suggest that PCT cut off value of 0,69 ng/ml predicts sepsis and that, in septic patients, peak PCT levels of 50 ng/ml was noted in deceased septic patients.The same result was found by many studies such as Heimberg et al.14Also, elevated PCT levels without decrease, in the present study, revealed a complicated course and indicated a worse prognosis. This phenomenon has been suggested in other studies.17,20In our study, even though prospectively conducted, there are many factors associated with sepsis and worse prognosis of burned patients that are not completely controlled, and it would be interesting to explore whether PCT has the potential of affecting diagnosis and prognosis of sepsis in burned patients favourably. Early diagnosis of sepsis is essential in severely burned patients (TBSA >20%). PCT seems to have valuable characteristics to be a reliable marker for systemic infection and sepsis in these patients.

Table V. Levels of PCT in sepsis.

Table VI. PCT cut-off value in different studies.

Conclusion

PCT assay can be a helpful adjunct to clinical diagnosis of sepsis and holds promise as a method for reducing antibiotic exposure in the critically ill patient. Procalcitonin appears to be a powerful marker of sepsis in burn patients. It is sensitive, specific, reliable and easy to measure. PCT determination offers an opportunity to burn intensive care specialists to make an early decision of any changes in the antimicrobial regimen as well as in monitoring of the response to therapy.

Acknowledgments

AcknowledgementsWe thank all authors for their contributions to the study design and for assisting in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, as well as for their involvement in writing the manuscript and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

This paper was accepted on Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters

References

- 1.Moyer E, Cerra F, Chenier R, Peters D, Oswald G, Watson F, Yu L, Mcmenamy RH, Border JR. Multiple systems organ failure: VI. Death predictors in the trauma-septic-state—The most critical determinants. J Trauma. 1981;21:862–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bone RC. Let’s agree on terminology: Definitions of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:973–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199107000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finnerty CC, Herndon DN, Przkora R, Pereira CT, Oliveira HM, Queiroz DM, et al. Cytokine expression profile over time in severely burned pediatric patients. Shock. 2006;26:13–9. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000223120.26394.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray CK, Hoffmaster RM, Schmit DR, Hospenthal DR, Ward JA, Cancio LC, et al. Evaluation of white blood cell count, neutrophil percentage, and elevated temperaturesas predictors of bloodstream infection in burn patients. Arch Surg. 2007;142:639–42. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.7.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenhalgh DG, Saffle JR, Holmes JH, et al. American Burn Association consensus conference to define sepsis and infection in burns. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:776–9. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181599bc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider HG, Lam QT. Procalcitonin for the clinical laboratory: A review. Pathology. 2007;39:383–90. doi: 10.1080/00313020701444564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harbarth S, Holeckova K, Froidevaux C, Pittet D, Ricou B, Grau GE, et al. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:396–402. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2009052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS (2003) 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definition conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1250–6. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garnacho-Montero J, Garcia-Garmendia JL, Barrero-Almodovar AE, Gimenez FG, et al. Impact of adequate empirical antibiotic therapy on the outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2742–51. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000098031.24329.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ugarte H, Silva E, Mercan D, De Mendonc A, Vincent JL. Procalcitonin used as a marker of infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:498–504. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199903000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavrentieva A. CRP – PCT Intérêt en pratique clinique. Burns. 2007;33:189–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gramm HJ, Beier W, Zimmermann J, Qedra N, Hannemann L, Boese-Landgraf J. Procalcitonin (Pro-CT)- A biological marker of the inflammatory response with prognostic properties. Clin Intens Care. 1995;6:71. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeni F, Viallon A, Assicot M, Tardy B, et al. Procalcitonin serum concentrations and severity of sepsis. ClinIntens Care. 1994;5:2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Heimburg D, Stieghorst W, Khorram-Sefat R, Pallua N. Procalcitonin – a sepsis parameter in severe burn injuries. Burns. 1998;24:745–50. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(98)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressel J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, et al. Earlygoal-directedtherapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barati M, Alinejad F, Bahar MA, Tabrisi MS, Shamshiri AR, Bodouhi NO, Karimi H. Procalcitonin, C-reactive Protein ESR and WBC Count: Marker of Sepsis in Burn Patients. Burns. 2008;34:770–4. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bargues L, Chancerelle Y, Catineau J, Jault P, Carsin H. Evaluation of serum procalcitonin concentration in the ICU following severe burn. Burns. 2007;33:860–4. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neely AN, Fowler LA, Kagan RJ, Warden GD. Procalcitonin in pediatric burn patients: an early indicator of sepsis? J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:76–80. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000105095.94766.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venet C, Tardy B, Zéni F. Marqueurs biologiques de l’infection en réanimation chez l’adulte: Place de la procalcitonine. Réanimation. 2002;11:156–71. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gramm HJ, Beier W, Zimmermann J, Qedra N, Hannemann L, Boese-Landgraf J. Procalcitonin (Pro-CT)- A biological marker of the inflammatory response with prognostic properties. Clin Intens Care. 1995;6:71. [Google Scholar]