Summary

This study has developed a learning kit for the prevention of domestic burns in childhood. The main objective was to trial an educational package for children (nursery and primary classes), for the prevention of burns, to be implemented through education in schools. The educational kit comprises posters, information leaflets, comic books, and pre and post education evaluation materials for school children, parents and teachers. Recipients of the preliminary study were the students of nine schools in the eight Italian cities where Burn Centers are located. In order to reach the target groups of children, it was necessary to identify the most effective communication strategy to convey the burn prevention message. For nursery school children, it was not possible to use tools with written texts alone, as they were not yet literate. Moreover, even for older children, it was necessary to find an attractive tool to catch their attention and interest, promoting the understanding and memorization of lessons learned. The most suitable means was found to be comic strips, allowing the messages to be conveyed through images as well as words. A total of 370 children (195 from nurseries and 175 from primary schools) participated in the trial of the educational kit. Overall, for every environment represented in the evaluation table, the ability to recognize the dangers among both the pre-school and primary school children increased significantly after the training activity. In conclusion, the educational kit has been positively assessed.

Keywords: school health promotion, health communication, burns, accident prevention, burn centers

Abstract

Cette étude a permis de mettre au point un kit d’apprentissage pour la prévention des brûlures domestiques chez les enfants. L’objectif principal était d’expérimenter un ensemble éducatif pour enfants (crèches et écoles primaires), pour la prévention des brûlures, à mettre en oeuvre à travers des actions d’éducation dans les écoles. Le kit éducatif est composé de posters, de brochures d’information, de bandes dessinées, et d’un matériel d’évaluation pré et post enseignements, pour enfants, parents et enseignants. Cette’étude préliminaire a rassemblé les élèves de 9 écoles, appartenant aux 8 villes des Centres de grands brûles en Italie. Concernant l’éducation des enfants, il était nécessaire d’identifier la stratégie de communication la plus efficace pour leur transmettre les messages de prévention. Pour les élèves de maternelle, il n’a pas été possible d’utiliser des outils avec textes, puisqu’ils n’étaient pas encore capables de lire et écrire; en outre, même pour les enfants plus âgés, il était nécessaire de trouver un outil attrayant pour attirer leur attention et susciter leur intérêt, promouvoir la compréhension et la mémorisation des leçons apprises. La bande dessinée a été jugée l’outil le plus approprié (langage complexe qui utilise l’outil verbal et les codes iconiques).Au total, 195 enfants de maternelle et 175 d’écoles primaires ont participé à l’évaluation du kit pédagogique. Nos résultats démontrent que, pour chaque environnement représenté dans le tableau d’évaluation, la capacité à reconnaître les dangers a augmenté d’une manière significative après la formation aussi bien dans le groupe des élèves de maternelle que dans celui des élèves d’écoles primaires. En conclusion, le kit pédagogique a été évalué positivement.

Introduction

Injuries and burns are a major public health problem in Italy, as in the other industrialized countries, especially among children for whom injury is the first cause of death.1 The data from the Italian Hospital Discharge Register (HDR) from 2005 to 20092 indicate that 71% of inpatients with pediatric burns (0-14 years) are children under 4 years old. If we consider the inpatients for burns up to 9 years old, this proportion rises to 86%. In the SINIACA- IDB Surveillance System, more than 20 hospitals throughout Italy registered the circumstances of the burn accidents. Pediatric burns have a psychological and social impact on the victims, as well as causing aesthetic and functional damage. Furthermore, the costs of pediatric burns are not to be underestimated. We assess a direct cost for the National Health Care Services of at least 15 million euros per year.

With regards to burn prevention, the active participation of children is fundamental because many situations in which children may be at risk cannot be totally avoided by adult intervention alone. Both children and parents (or care givers) must be made directly responsible and aware of the potential risks linked to their behavior in the home environment, where most burn accidents occur. From a very young age, children can be educated toward the prevention of burns via appropriate communication methods. Education in schools is the best way to teach children about safety in the home and how to identify and avoid the risks of burns, as well as their health consequences.

The PRIUS project: objectives, methods and materials

PRIUS project (prevention of burn accidents among school-aged children), funded by the Ministry of Health (CCM- National Centre for Disease Control and Prevention) and coordinated by the Italian National Health Institute (ISS), has proposed a learning path for the prevention of domestic burn accidents in childhood (3-8 years) and for the promotion of first aid standards.3

The target group comprises pre-school and primary school pupils, as well as their teachers and parents, who are to be trained at their schools in the main Italian cities where Burn Centers are located. The main objective of the project was the trial of an educational package for children (kindergarden and primary classes), for the prevention of burn accidents, to be implemented through education in schools. The instructional and educational package comprises posters put up in classrooms, information leaflets for parents and teachers (level II trainers), comic books for children, pre and post education evaluation boards for children, and pre and post evaluation questionnaires for parents, teachers, and primary school children. Specifically for trainers (level I and II), a manual in the CD-ROM format was also created.

Recipients of the preliminary study were the students of nine schools in Italy, sited in eight cities with Burn Centers (Brindisi, Milan, Naples, Padua, Palermo, Rome, Turin and Verona). The project included: a) training performed by the Burn Centers staff (level I trainers) for teachers and school principals (level II trainers); b) training of students, under the coordination of school principals and teachers; c) evaluation of pre and post training phases, in order to assess the level of learning; d) distribution of educational materials especially designed for teachers and children (comics, booklets, posters, multi-media material). The training recipients acquired specific knowledge of epidemiological elements of burn accidents in childhood (teachers and parents) and general knowledge on the effect of burns, risk factors, appropriate behaviors to avoid burns in the home, and basic first aid basic (teachers, parents and children).

In targeting children, it was necessary to identify the most effective form of communication to convey our messages. While primary school children are generally sufficiently literate to use text-based tools, this is not the case for nursery school children, who also possess less developed verbal reasoning skills. However, regardless of literacy levels, for all children it was important to find an attractive tool to catch their attention and interest, promoting the understanding and memorization of the burn prevention lessons learned. The most suitable tool was found to be comics, making use of words (inside speech bubbles and captions) and, most importantly, pictures.4-9 Initially, comic strips arose for entertainment purposes, although they showed pedagogical possibilities early on. The history of comics as an educational tool is complex and has gone through various stages, with mixed success. At first, they were regarded as a danger to the education of children (undergoing censorship in the United States and elsewhere). By the 1970s and 80s, especially in the United States, comics had been revalued from an artistic and literary point of view, with their use widening to include educational purposes within the school curricula.9-24 Among the many examples of programs that currently use comic strips as teaching tools, of particular note is the pilot program “Comics in the Classroom”;9,25 in Italy, the national project “Banchi di Nuvole”,26 the comic book “I jeans di Garibaldi”,9 and the European project “EduComics”.9,27

In addition to educational use, comics have been widely used in recent decades, including as an instrument of public communication for health prevention purposes or raising the awareness of social issues. For example, the Italian National AIDS Campaign “Lupo Alberto”,28,29 FAO’s campaign entitled “Nutrire la mente, combattere la fame” (“Feeding Minds, Fighting Hunger”), the European Project “Common Values” for the integration of immigrants, the comic book on the Holocaust distributed in Germany (entitled “Die Suche”),9 the campaign against drugs using Dylan Dog cartoons, the one based on Disney comics to explain economics to children in the financial newspaper “Il Sole 24 Ore”,29,30 the campaign for the prevention of road traffic accidents “Vacanze coi fiocchi”,31 and the campaign “Sicuramente”, promoted by Fondazione ANIA and Walt Disney Italia.32 With specific reference to the prevention of burns, we can mention the “Family Circus” campaign for the NFPA (National Fire Protection Association, USA) and, in the Euro-Mediterranean context, the BurNet project, conceived and promoted by MBC (Mediterranean Council for Burns).

According to Retalis,9 the presence of verbal and iconic elements in the comics can make them an innovative tool in pedagogy, able to involve students in a way that makes use the visual world in which they live. In Japan, for example, education through comics is a natural consequence of the study of writing.29 However, even without appealing to more complex concepts (sometimes conflicting) - developed in the frameworks of semiotics of iconic signs,33,34 communication theory35,36 or visual culture37-39 - it is quite natural that, at an early age, with limited or no literacy and verbal skills, people prefer stories told through images rather than exclusively through plain text or words. This is because humans learned to communicate through images before written words, which are also derived from extreme and complex graphical representation and abstraction of iconic signs.40

Another theory to support the effectiveness of comics as an educational tool is Clark and Paivio’s learning theory known as “dual encoding theory”, which stresses the importance of images in cognitive tasks. The authors argue that the recognition and storing of concepts expressed in the textual form would be reinforced by the presence of both visual and verbal information.9,41 Many other researchers have studied the benefits of using comics in education, 15 identifying the following strengths in particular:

Visual appeal: the natural human attraction for images allows comics to capture and hold the interest of the learner;15

Enhanced empathy: comics tell a story which relies on the interaction between verbal and iconic codes to “humanize” a given topic, resulting in an emotional bond between the reader and the characters of the comic story;9,42

Fixed images: Williams43 cites the permanent visual component of comics, as opposed to movies and animated cartoons, in which the medium dictates the rhythm at which the vision progresses. By contrast, with comics, the reading time progresses at the pace of the reader9,15 and the amount of time granted to review, assimilate and imagine how to behave or to assume the role or the attitude shown is unlimited.44

User-friendly format: comics can serve as an intermediate step toward difficult disciplines and concepts, offering a less challenging approach to readers with learning difficulties or those reluctant to tackle a particular topic. For those already experienced and motivated in a given topic, comics can provide inspiration and stimulus to a greater interest in more challenging texts;15

Aid to developing thinking skills: the ability of analytical and critical thinking can be developed through comics according to Versaci.42

Thus, comics - in using iconic language, that is almost universally understood and which can trigger identification or projection mechanisms - can be used for teaching in different disciplines and educational contexts.44,45 The use of comics, being reproducible on paper, was fundamental for the feasibility of the project and the possibility of dissemination of our methods and tools. In fact, we were able to share these tools in electronic format and then reproduce them simply by printing on paper. No special tools were required in addition to paper and pencil, and the readily available low-cost material used improved the project viability.

Results

The PRIUS project comics

The comic book product for the PRIUS project was designed with the intention of allowing the comprehension and memorization of the burn prevention concepts in children, including those who are very young and not yet able to read. For this reason, we made use of a professional illustrator and the educational training support of the SPES Speranza Onlus Association, which had specific expertise in the field of prevention of burns. Instructions were provided to the illustrator, as a guide to the contents of the PRIUS comics. In fact, we think it is important that the information provided to prepare the comics is evidencebased. So that the situations and circumstances which represent a greater risk of childhood burns are represented in a precise and effective way. This script was written based on a thorough analysis of the case studies of burns and their external causes from the observation of individual clinical reports (anamnestic in particular) from the emergency departments surveillance system SINIACA-IDB, held by the ISS.46

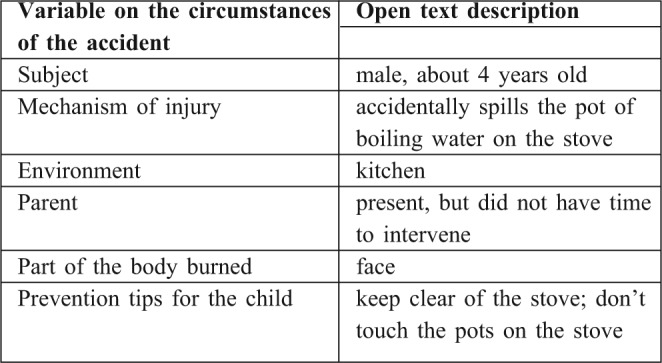

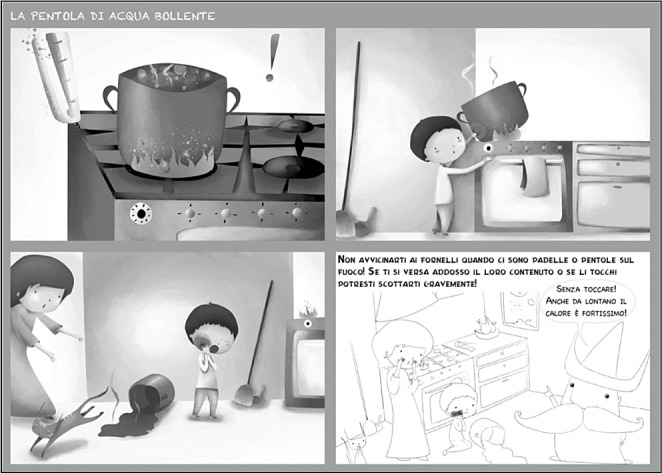

Below is an example of information given relating to the risks of burns in the kitchen, coupled with the comic strip created by the illustrator using the instructions provided from epidemiological evidence (Table I, Figs. 1 and 2).

Table I. Example of risk situation.

Fig. 1. Comic book cover – PRIUS Project.

Fig. 2. Comic book page on the dangers within the kitchen environment.

The PRIUS project comic book is entitled “A scuola di sicurezza con il Mago Teodoro e la Fata Celeste” (“The school of safety with Theodore Wizard and Celeste Fairy”). It is composed of 24 pages including the cover, and is divided into four main home environments: kitchen, bathroom, living room and outdoors. For each indoor environment there is a presentation page, four tables with regular comic panels and a final full page, in addition to a summary of the hazards relating to that environment. Only the external environment is represented entirely by a single table. Each page of comic strips includes a black and white panel, allowing a degree of interactivity, as children can color the pictures themselves, thus providing entertainment as well as training. The comic book images were colored using digital painting techniques, giving a more current effect to a classic product. The choice of colors were obviously bright, helping to provoke an immediate interpretation, softened with delicate shading designed to create a pleasant experience.

Graphically, this is the so-called “iconic image”,7 that is a very stylized graphic line, where the images and the characters are extremely simplified compared to reality. This technique facilitates the reading and understanding of situations by small children and ensures rhythm and lightness in pages rich in detail. The same author points out that the more the sign is iconic, stylized, the more universal the appeal the represented scene. The elimination of details in graphical images also increases the humorous and childish aspect, alleviating the “threat” implicitly inherent in the subject (accidents and burns), and making the text more suitable for young children.6 The comic panels are all rectangular, with straight edges and have a stable rhythm with regard to the size and position, with the exception of full pages, which constitute a completion and an aesthetic rupture of the rhythm.47 All the scenes are shown from a child “eye-level” perspective, which in the language of cinema is known as reinforcement of the realism effect and of involvement in the represented scene.6

The protagonists and guides of the comic book story are a Wizard and a Fairy that can be considered, in relation to the narrative structure of the story, magical Helpers. They guide the hero - represented by children depicted in the text - to the acquisition of the necessary Competence to achieve the Object of value. Children, at the ‘level of enunciation’, represent the enunciators of the story, i.e. the child to which the story turns into reality.48,49 The magic, introduced in the comics through the two Helpers, a Fairy and a Wizard, appeals greatly to older child-readers, but even more so to the younger ones who, at 3-5 years old, are used to listening to fairy tales where magic prevails. The Object of value, in this case, is represented by “Safety”, the ability to avoid a burn accident, while the necessary Competence is the “Knowledge” that the child must acquire in the context of the correct action to be taken. Another important magic protagonist of the comic book story is the “Dragon”, indirectly and symbolically represented by fire. In fact, the dragon, in fairy tales, is a manyheaded igneous and threatening being.50 Many, therefore, are the forms the dragon can take, all generally related to fire, the protagonist and the “Anti-subject” of the story.51

Evaluation of the educational kit and conclusions

A total of 195 nursery children and 175 primary school children participated in the trial of the educational kit. Overall, the post-training evaluation revealed that, for every environment represented in the comic book, the ability of both the pre-school and primary school children to recognize the dangers was higher in the trained than in the pretrained groups. For the younger children, who were assessed on 41 risk situations presented in the tables (e.g. a bot of boiling water on a stove, lit gas hobs in the kitchen), on only five occasions did they fail to show an increase in their ability to recognize the danger post-training. As an example of improved recognition, we can cite the case of the scene of a pot of boiling hot soup on the kitchen table: before the training, 73.1% of respondents recognized it as dangerous; after the training this figure rose to 97.5% (difference = 24.4; p <0.0000). All the primary school children showed an increase in the ability to recognize the dangers after the training activity across all 47 risk situations represented in the tables (e.g. a child being held by a parent who is drinking a hot cup of coffee). Another example is the case of the bottle of flammable liquid at the foot of the barbecue: before the training, 36.0% of respondents recognized this as dangerous; after the training this figure rose to 65.7% (difference = 29.7; p <0.0000).

Conclusion

Overall, the evaluation of the risk perception of all the children involved from the nursery and primary schools has shown the educational kit to be a success, having produced an increase in their ability to recognize the dangers in each of the examined environments. Particularly relevant are the learning results of the younger children who are still unable to read, as they would have been expected to exhibit, on average, a lower level of development in verbal reasoning and processing concepts compared to the older ones.

In line with existing communication and pedagogic theories, our visual tool, in the form of comic strips, was shown to be suitable for conveying the desired concepts, even to very young children. Moreover, in enabling us to get competent answers from the children about the kinds of risks of burns illustrated and the proper behaviors required to avoid them, we could confirm that comics were sufficient to teach about both dangers and preventive measures. Furthermore, verbal feedback from the teachers suggested the comics were appreciated by the children and were thus a valid mode for transmission, understanding and storage of risk factors and preventive behaviors necessary to avoid childhood burn injuries. The use of simple tools for this project has allowed us to easily conduct our activities in the sample schools and will make future dissemination feasible, even in disadvantaged areas. Finally, as the educational kit has been validated in terms of its suitability as a teaching tool, it can be rolled-out on a large scale across educational institutions for the prevention of burns.

References

- 1.Bauer R, Injuries in the European Union Statistics Summary 2005-2007. Vienna: 2009. Report 2009 EU Injury Database, [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapporto annuale sull’attività di ricovero ospedaliero – Dati SDO 2008. Ministero della salute – Dir. Gen. Programmazione Sanitaria – Uff. VI,; Roma: 2009. (in Italian) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cedri S, Longo E, Masellis A, Briguglio E, Pitidis A, Gruppo di lavoro PRIUS e Gruppo di lavoro SINIACA La prevenzione degli incidenti da ustione in età scolastica: Il progetto PR.I.U.S. Not Ist Super Sanità. 2013;26:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.La funzione, la norma e il valore estetico come fatti sociali. Semiologia e sociologia dell’arte. Einaudi; Torino: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The History of the Comic Strip. University of California Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fumetto & Arte sequenziale. Vittorio Pavesio Productions; Torino: 2006. (in Italian) (original edition: “Comics & Sequential Art”, Poorhouse Press, 1990) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capire il fumetto. L’arte invisibile. Vittorio Pavesio Productions; Torino: 1996. (in Italian) (original edition: Understanding Comics, the invisible art, Harper Perennial, New York, 1994) [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Aesthetics of Comics. Penn State University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.State of the Art Comics in Education, Project Deliverable Report. EduComic Project; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sones WWD. The Comics and Instructional Method. J Educ Soc (American Sociological Association) 1944;18:232–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorndike RL. Words and the comics. J Exp Educ. 1941;10 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill GE. Word distorsions in comic strips. Elem School J. 1943;43 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchinson K. An experiment in the use of comics as instructional material. J Educ Soc. 1949;23:236–45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruenberg S. The Comics as a Social Force. J Educ Soc. 1944;18:204–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gene LY. History of Comics in Education. [Accessed January 28, 2015]. [http://humblecomics.com. web site]. Copyright Gene Yang 2003.

- 16.Seduction of the Innocent. The influence of comic books on today’s youth. Rinehart and Company Inc; NewYork and Toronto: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Comic book nation: The transformation of youth Culture in America. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorrell L, Curtis D, Rampal K. Book worms without books? Students reading comic books in the school house. J Pop Cult. 1995;29:223–34. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fumetti. Guida ai comics nel sistema dei media. Datanews; Roma: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Psicologia del fumetto. Guaraldi; Firenze: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenke K. The careful use of comic books. Read Teach. 1981;34:592–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haugaard K. Comic books: Conduits to culture? Read Teach. 1973;27:54–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alongi C. Response to Kay Haugaard: Comic books revisited. Read Teach. 1974;27:801–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brocka B. Comic books: in case you haven’t noticed they’ve chanced. Media and Methods. 1979;15:30–2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The pilot program “Comics in the Classroom”. [Accessed February 10, 2015]. [http://marylandpublicschools.org. web site]

- 26.The Italian National Project “Banchi di Nuvole”. [Accessed March 7, 2015]. [http://archivio.pubblica.istruzione/news/banchidinuvole. web site]

- 27.The European project “EduComics”. [Accessed February 11, 2015]. [http://educomics.org. web site]

- 28.The Italian National AIDS Campaign “Lupo Alberto”. [Accessed March 6, 2015]. [http://salute.gov.it. web site]

- 29.Giorgio C. Disegno letterario. Il fumetto come strumento educativo. [Accessed February 11, 2015]. [http://rivista.ssef.it. web site]

- 30.Dizionario dei fumetti. Garzanti Editore; Milano: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The campaign for the prevention of road accidents “Vacanze coi fiocchi”. [Accessed March 5, 2015]. [http://vacanzecoifiocchi.it. web site].

- 32.The campaign “Sicuramente”, promoted from Fondazione ANIA and Walt Disney Italia. [Accessed March 6, 2015]. [http://fondazioneania.it. web site].

- 33.Manuale di Semiotica. Roma-Bari: Laterza; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trattato di semiotica generale. Bompiani; Milano: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 35.La galassia Gutenberg. Nascita dell’uomo tipografico. Gruppo Editoriale L’Espresso; Roma: 1991. (original edition: “The Gutenberg Galaxi. The making of typographic man”, University of Toronto Press, 1962) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gli strumenti del comunicare. Il Saggiatore; Milano: 2008. (in Italian) (original edition: “Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man”, Gingko Press, 1964) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Introduzione alla cultura visuale. Meltemi; Roma: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teorie delle comunicazioni di massa. Il Mulino Ed; Bologna: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark JM, Paivio A. Dual coding theory and education. Educ Psychol Rev. 1991;3:149–210. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Versaci R. How comic books can change the way our students see literature: One teacher’s perspective. Eng J. 2001;91:61–7. [Google Scholar]

- 43.The comic book as course book: why and how, Annual Meeting of the Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. Long Beach: CA; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinciroli F, Reati A. Il fumetto come strumento psicopedagogico. [Accessed January 27, 2015]. [http://educare.it. web site] April 11, 2011.

- 45.Heroes in the Classroom: Comic Books in Art Education. Art Education; 2001. p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pitidis A. Incidenti domestici in Italia: sorveglianza, modelli e azioni di prevenzione. Rapporto del Sistema Informativo Nazionale sugli Infortuni in Ambienti di Civile Abitazione (SINIACA) Istituto Superiore di Sanità; Roma: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barbieri D. Nel corso del testo. Una teoria della tensione e del ritmo. Bompiani; Milano: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Del senso 2: narrativa, modalità, passioni. Bompiani; Milano: 1985. (in Italian) (original edition: Du sens II, Seuil, Paris, 1983) [Google Scholar]

- 49.La teoria dell’enunciazione. Le origini del concetto e alcuni più recenti sviluppi. Protagon; Siena: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morfologia della fiaba. Le radici storiche dei racconti di magia. Newton Ed; 2012. (in Italian) (original edition: “Morfologija e skazki e Istoriceskie korni volšebnoj skazki”, Leningrado, 1928) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Semiotica. Dizionario ragionato della teoria del linguaggio. La Casa Usher; Firenze: 1986. (in Italian) (original edition: Sémiotique. Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage, Hachette, 1979) [Google Scholar]