Abstract

Background

Epidemiological and experimental studies have suggested that exposure to particulate air pollution may promote progression of atherosclerosis.

Methods

In the present study, the characteristics and trends of the research field of particulate matter (PM) and atherosclerosis were analyzed using bibliometric indicators. Bibliometric analysis was based on original papers obtained from PubMed/MEDLINE search results (from 1973 to 2014) using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. A fully-detailed search strategy was employed, and articles were imported into the Thomson Data Analyzer (TDA) software.

Results

The visualizing network of the collaborative researchers was analyzed by Ucinet 6 software. Main research topics and future focuses were explored by co-word and cluster analysis. The characteristics of these research articles were summarized. The number of published articles has increased from five for the period 1973–1978 to 89 for the period 2009–2014. Tobacco smoke pollution, smoke and air PM were the most studied targets in this research field. Coronary disease was the top health outcome posed by PM exposure. The aorta and endothelium vascular were the principal locations of atherosclerotic lesions, which were enhanced by PM exposure. Oxidative stress and inflammation were of special concern in the current mechanistic research system. The top high-frequency MeSH terms were clustered, and four popular topics were further presented.

Conclusion

Based on the quantitative analysis of bibliographic information and MeSH terms, we were able to define the study characteristics and popular topics in the field of PM and atherosclerosis. Our analysis would provide a comprehensive background reference for researchers in this field of study.

Keywords: Bibliometric analysis, Particulate matter, Atherosclerosis, Research tendency, Popular topics

Background

Exposure to air particulate matter (PM) may result in various diseases including cardiovascular diseases (CVD) such as atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, stroke, myocardial ischemia, coronary diseases and cardiac arrhythmia. Its etiology and pathogenic mechanisms may be complex, which include pulmonary and systemic inflammation, accelerated atherosclerosis and altered cardiac autonomic functions [1, 2]. PM contributes to increased cardiac risk by initiating and promoting atherosclerotic progression, which is the underlying cause of most cardiovascular diseases [3]. There is ample epidemiological, clinical and experimental evidence supporting the association of PM with atherogenesis [4–7]. Related research on PM exposure-enhanced atherosclerosis has attracted greater attention and is becoming an important, rapid-progressing field in the coming years. Therefore, it is necessary to survey bibliometric characteristics and portray the overall trend of these research fields.

Bibliometrics refers to a research methodology employed in library and information sciences, which utilizes quantitative analysis and statistics to describe the bibliographic information of articles (year publication, title, authors, publisher, affiliations, etc.) within a given topic, field, institution, and/or country [1, 8]. Recently, bibliometrics has been used to explore trends in biomedical, medical and environmental research fields; such as the mapping of global drinking water from 1992 to 2011 [8], air PM on the cardiovascular system [1], urban health for the period 1978–2012 [1], stem cell research in Iran [9], cardiovascular research from Latin America from 1999 to 2008 [10], and ophthalmology research from 1997 to 2009 [11]. Bibliometrics applies quantitative and statistical methods to analyze a variety of phenomena across scientific literatures. Literature data are mainly derived from international literature databases such as PubMed/MEDLINE [1], Springerlink [12], and Web of Science [13]. In the present study, we attempted to analyze the characteristics and trends within the research fields of PM and atherosclerosis using the bibliometric approach by conducting a search on the PubMed/MEDLINE database using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms.

Methods

Data sources

The database used in the present study was PubMed/MEDLINE, which is provided by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) in America. The NLM covers the largest number of publications on life sciences and biomedical research.

Search strategy

MeSH, compiled by NLM for its bibliographies and cataloging [14], were used to perform the literature search and exploration of popular topics in these research fields. As illustrated in Table 1, these MeSH terms (2015 MeSH) were combined using the Boolean operator AND. The first group of MeSH terms included PM and the expanded versions of the MeSH term such as particle size, air pollution and air pollutants. The second group of MeSH terms included atherosclerosis and the expanded versions of the MeSH of arteriosclerosis, atherosclerotic plaque, carotid artery diseases and coronary diseases.

Table 1.

Reference search strategy

| Connector | Field | Parameter |

|---|---|---|

| Mesh Terms | (Particulate Matter) OR ((Air Pollution) OR (Air Pollutants) AND (Particle Size)) | |

| AND | Mesh Terms | (Atherosclerosis) OR (Arteriosclerosis) OR (Coronary Disease) OR (Plaque, Atherosclerotic) OR (Carotid Artery Diseases) |

| AND | Publication type | Journal Article |

| NOT | Publication type | Review |

| AND | Language | English |

Data collection

Data was obtained through a comprehensive literature search of the PubMed/MEDLINE database on the 8th of January, 2015. The eligible records of 259 articles were downloaded. Bibliographic information included the title, abstract, name of authors, journal title, year of publication, and the corresponding authors’ address.

Data analysis

These records were imported into the Thomson Data Analyzer software version 3.0 (TDA; Thomson Reuters Co., New York, NY, USA), which could provide a global view of the technology area. In order to analyze characteristics and trends, the data analysis process consisted of five parts: data cleaning, bibliographic information analysis, MeSH terms analysis, co-occurrence of word (co-word) analysis, and cluster analysis. In order to ensure the accuracy of these results, reduplicates and conflicting data were cleaned using the TDA software, which offers an efficient and accurate automatic data cleansing tool. For subsequent analysis, a bibliographic information database with 259 articles and 683 MeSH terms used during the period 1973–2014 was established. TDA was used to process and analyze bibliographic information (year of publication, journal title, affiliation, author and country).

The visualized network of the collaborative researchers was analyzed by Ucinet 6 (Analytic Technologies Co., Lexington, KY, USA) software, which is considered the most popular social network analysis software and features a strong matrix analysis function. The 50 × 50 co-occurrence frequency matrix of the 50 most published authors was calculated to reflect the collaborative relationship between top researchers. The betweenness centrality for measures of structural centrality in social networks can reflect the degree of centralization of the research network [15]. MeSH terms were ranked according to frequency. The top 225 MeSH terms (with a cumulative frequency of 74.2 %) were defined as high-frequency terms for the subsequent research trend analysis.

Co-occurrence of word (co-word) analysis is a basic and important approach for themes exploration, which include three steps: measurement of the links between terms, organization of clusters, and concluding the topics [1]. The 225 × 225 co-occurrence frequency matrices of the top 225 MeSH terms were conducted using the TDA software. After conducting the cluster analysis with SPSS software version 17.0 (Chicago, IL, USA), the MeSH terms were combined to create 12 clusters according to the degree of similarity. Based on the cluster analysis of high-frequency MeSH terms, popular topics in the research fields of PM and atherosclerosis were concluded.

Results

Characteristics of publications

Publication outputs

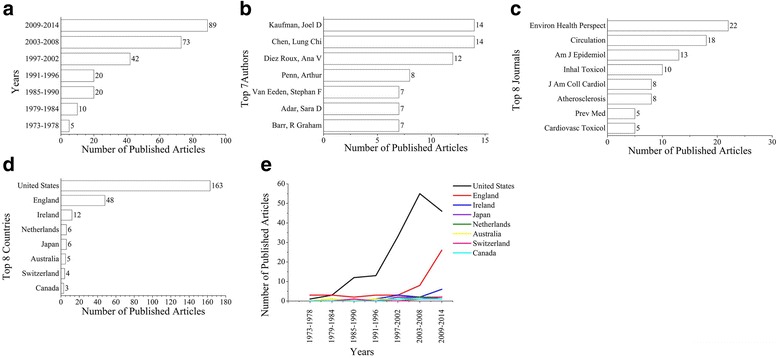

Due to the large number of publications retrieved, more attention was given to the research area of PM and atherosclerosis. As shown in Fig. 1a, the number of published articles increased from five occurrences for the period 1973–1978 to 89 occurrences for the period 2009–2014. As shown in Fig. 1b, Dr. Kaufman and Dr. Chen LC had authored most of the published articles in the field of PM exposure-related atherosclerosis. As shown in Fig. 1c, journals on Environmental Health Perspectives and Circulation had covered the largest portion of published articles. As shown in Fig. 1d, USA was the top country that conducted related studies. As shown in Fig. 1e, there has been an increasing trend of published articles from other countries.

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of published articles on the study of PM exposure-related arteriosclerosis. The numbers of papers for every 6-year segment from 1973 to 2014 are shown in (a). The numbers of papers of the top authors, journals and countries are shown in (b), (c) and (d), respectively. The trends of published articles for the top eight countries during the period 1973–2014 are shown in (e)

Characteristics of the top fifty researchers in the field of PM exposure-related atherosclerosis

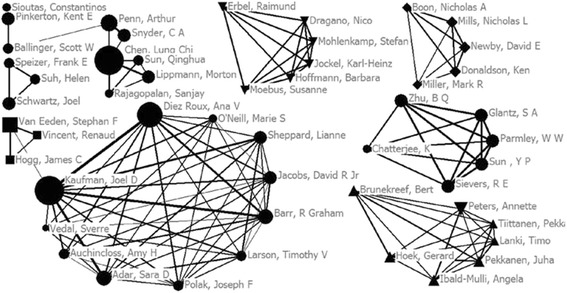

As shown in Fig. 2, the research network included USA, Germany, Finland, Canada and UK. Researchers from USA constituted the largest research network. Furthermore, Dr. Kaufman and Dr. Chen LC published most of the articles in the field of PM exposure-related atherosclerosis, but Dr. Kaufman was the central researcher and acted as a bridge that connected the whole network (betweenness centrality = 31).

Fig. 2.

Collaborative relationship network of the top 50 researchers. The size of the nodes represents the number of papers. The size of the lines represents the close degree of co-authors. The shapes of the nodes represent different countries (circle represents the US, down-triangle represents Germany, box represents Canada, up-triangle represents Finland, and diamond represents UK)

Characteristics of the high-frequency MeSH terms

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the MeSH terms were ranked according to frequency and were classified into eight categories including PM, objects-human, objects-animals, objects-lesions, main outcomes, mechanisms, main methods and factors. Epidemiological studies, in which ‘middle-aged’ and ‘aged’ populations were the main focus, comprised of a significant proportion of the research field of PM exposure-related atherosclerosis; and were mostly cohort studies. Mice, gene knockout mice and disease model animals were the most frequently chosen subjects in vivo. Oxidative stress and inflammation were the most popular mechanisms hypothesized. The methods of cell culture in vitro were very important in toxicological and mechanistic studies, and endothelial cells were the major experimental model. Tobacco smoke pollution, smoke and air PM were the most studied targets in the research fields. The aorta and endothelium vascular were the principal atherosclerosis lesion locations, which were enhanced by PM exposure. Coronary disease was the top health outcome posed by PM exposure. Time, gender and diet were the top three risk factors that may influence the degree of atherosclerosis accelerated by PM exposure.

Table 2.

Characteristics of high-frequency MeSH terms

| PM | Objects-humans | Objects-animals | Objects-lesions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | MeSH terms | Freq. | MeSH terms | Freq. | MeSH terms | Freq. | MeSH terms | Freq. |

| 1 | Tobacco Smoke Pollution | 149 | Humans | 192 | Animals | 80 | Aorta | 37 |

| 2 | Smoke | 84 | Male | 186 | Mice | 45 | Endothelium, Vascular | 26 |

| 3 | Particulate Matter | 70 | Female | 150 | Mice, Knockout | 34 | Tunica Intima | 12 |

| 4 | Air Pollutants | 50 | Middle Aged | 108 | Disease Models, Animal | 20 | Carotid Arteries | 8 |

| 5 | Particle Size | 37 | Aged | 88 | Rabbits | 16 | Myocardium | 7 |

| 6 | Air Pollution | 33 | Adult | 87 | Rats | 8 | Brachial Artery | 6 |

| 7 | Vehicle Emissions | 16 | Aged, 80 and over | 22 | Chickens | 7 | Carotid Artery, Common | 6 |

| 8 | Carbon Monoxide | 14 | Adolescent | 16 | Dogs | 3 | Tunica Media | 6 |

Table 3.

Characteristics of high-frequency MeSH terms

| Main outcomes | Mechanisms | Main methods | Factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | MeSH terms | Freq. | MeSH terms | Freq. | MeSH terms | Freq. | MeSH terms | Freq. |

| 1 | Coronary Disease | 128 | Oxidative Stress | 19 | Cohort Studies | 24 | Risk | 97 |

| 2 | Atherosclerosis | 73 | Inflammation | 13 | Prospective Studies | 21 | Time Factors | 33 |

| 3 | Arteriosclerosis | 52 | Vasodilation | 11 | Cross-Sectional Studies | 19 | Sex Factors | 12 |

| 4 | Lung Neoplasms | 21 | Gene Expression Regulation | 8 | Questionnaires | 14 | Diet, Atherogenic | 11 |

| 5 | Heart Rate | 14 | C-Reactive Protein | 8 | Biological Markers | 13 | Antioxidants | 10 |

| 6 | Myocardial Infarction | 13 | Muscle, Smooth, Vascular | 8 | Follow-Up Studies | 13 | Vitamin | 9 |

| 7 | Blood Pressure | 12 | Vasoconstriction | 8 | Case–control Studies | 10 | Age Factors | 7 |

| 8 | Cardiovascular Diseases | 9 | Endothelial Cells | 7 | Cells, Cultured | 10 | Life Style | 5 |

Research tendencies and hotspots

Cluster analysis of the top 225 high-frequency MeSH terms was classified into 10 clusters, which explained 99.05 % of total variations. According to the roles of MeSH terms in the studies and relying on professional judgment, the terms in every cluster were categorized into objects, exposure variables, main outcome variables, factors, lesions, designs/methods and contents/mechanisms. Cluster analysis can group separate data types into clusters, and help identify valuable clues of possible research issues. After the synthetic analysis of the ten clusters, four research hotspots related to PM and atherosclerosis were identified, which provide a reference for further research in these fields (Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7). Results of the cluster analyses reflected the research tendencies in these research fields. Topic 1 was formed by combining Clusters 1, 3, and 9; Cluster 2 was combined with Cluster 4 to form Topic 2; Clusters 5, 7, and 8 were converged to form Topic 3; and Cluster 6 was combined with Cluster 10 to form Topic 4 (Table 8).

Table 4.

Cluster analysis of MeSH terms (Topic1)

| Cluster | MeSH terms |

|---|---|

| 1 | Objects: Humans; Male; Female; Middle Aged; Aged; Adult |

| Exposure variables: Tobacco Smoke Pollution | |

| Main outcome variables: Coronary Disease | |

| 3 | Exposure variables: Smoke |

| Main outcome variables: Arteriosclerosis; Aortic Diseases; Heart Diseases; Hypertension; Body Mass Index; | |

| Contents/Mechanisms: Apolipoprotein; Cholesterol; Antioxidants; Lipid; Lipoproteins LDL; Lipoproteins HDL; Hyperlipidemias; | |

| Peroxidation; Genetic Predisposition to Disease; Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances; Glutathione; Ascorbic Acid; Vitamin; Chromatography High Pressure Liquid | |

| Factors: Atherogenic Diet; Workplace; Health Education; Educational Status | |

| 9 | Objects: Child; Parents/psychology |

| Exposure variables: Cotinine | |

| Designs/Methods: Case–control Studies; Biological Markers | |

| Contents/Mechanisms: Vasodilation; Endothelium, Vascular; Vasodilator Agents; Nitroglycerin; Brachial Artery |

Table 5.

Cluster analysis of MeSH terms (Topic2)

| Cluster | MeSH terms |

|---|---|

| 2 | Objects: Aged-80 and over; Ethnic Groups; Continental Population Groups; Europe; USA; Spouses |

| Exposure variables: Air Pollutants; Air Pollution; Air Pollution-Indoor; Environmental Exposure; Occupational Exposure; Environmental Monitoring; Soot; Nitrogen Dioxide; Nitrogen Oxides | |

| Designs/Methods: Epidemiologic Studies; Cohort Studies; Prospective Studies; Cross-Sectional Studies; Follow-Up Studies; Questionnaires; Prevalence; Odds Rati; Proportional Hazards Models; Multivariate Analysis; Logistic Models; Longitudinal Studies; Linear Models; Confidence Intervals | |

| Main outcome variables: Carotid Intima-Media Thickness; Carotid Artery Diseases; Stroke; Cardiovascular Diseases; Vascular Calcification; Respiratory Tract Diseases; Pulmonary Disease-Chronic Obstructive; Lung Neoplasms; Neoplasms; Occupational Diseases; Sensitivity and Specificity; Tomography X-Ray Computed; Predictive Value of Test; Public Health; Comorbidity; Hospitalization; Cause of Death | |

| Factors: Time Factors; Sex Factors; Age Factors; Socioeconomic Factors; Life Style; Obesity; Health Behavior; Health Status | |

| 4 | Lesions: Tunica Intima; Carotid Arteries; Tunica Media |

Table 6.

Clusters analysis of MeSH terms (Topic3)

| Cluster | MeSH terms |

|---|---|

| 6 | Objects: Infant; Pregnancy; Adolescent; Aging; European Continental Ancestry Group; Rats; Rabbits; Chickens; Dogs; Great Britain; Africa; Canada/epidemiology |

| Exposure variables: Carbon Monoxide; Dust; Nitric Oxide; Sulfur Dioxide; Metals; Nanoparticles; Tars; Urban Health; Fires | |

| Designs/Methods: Retrospective Studies; Random Allocation; Single-Blind Method; Confounding Factors (Epidemiology); Marriage; Residence Characteristics; Models-Statistical; Regression Analysis; Analysis of Variance; Blood Chemical Analysis; Respiratory Function Tests; In Vitro Techniques | |

| Contents/Mechanisms: Inflammation; Muscle- Smooth-Vascular; Cytokines; Interleukin-6/metabolism; Carboxyhemoglobin; Immunohistochemistry; Platelet Aggregation/drug effects; Reactive Oxygen Species; Endothelin-1; Cell Movement; Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1/metabolism; Lipid Metabolism; Interleukin-1beta; Apoptosis; Myocytes-Smooth Muscle Leukocyte Count; Lipids/blood; Receptors-LDL; Fibrinogen; Aspirin; Temperature; Cyclooxygenase 2; Neutrophils; Macrophages/metabolism; Monocytes; Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid | |

| Main outcome variables: Cerebrovascular Disorders; Asthma; Lung Diseases; Diabetes Mellitus; Acute Disease; Disease Progression; Blood Pressure; Pulmonary Artery; Carotid Artery-Common; Blood Vessels; Brachiocephalic Trunk; Endothelins Arteries; Lung; Heart; Liver; Pneumonia; Intermittent Claudication; Mortality; Prenatal Exposure Delayed Effects | |

| Exposure variables: Particulate Matter; Particle Size; Inhalation Exposure; Vehicle Emissions; China | |

| 10 | |

| Designs/Methods: Cross-Over Studies; Double-Blind Method; Electrocardiography | |

| Contents/Mechanisms: Vasomotor System; Cardiovascular System; C-Reactive Protein/analysis; | |

| Main outcome variables: Myocardial Infarction; Myocardial Ischemia; Thrombosis; Heart Rate; Arrhythmias-Cardiac |

Table 7.

Cluster analysis of MeSH terms (Topic4)

| Cluster | MeSH terms |

|---|---|

| 5 | Objects: Endothelial Cells; Cell Line |

| Study designs and methods: Cells Cultured; Dose–response Relationship-drug; Microscopy | |

| Contents/Mechanisms: RNA Messenger; Gene Expression; Gene Expression Regulation; Up-Regulation; Antigens-CD; Heme Oxygenase-1, Tyrosine | |

| Main outcome variables: Vasoconstriction; Myocardium | |

| 7 | Contents/Mechanisms: Oxidative Stress; Superoxide Dismutase,Oxidants; Mitochondria; DNA-Mitochondrial, DNA Damage |

| 8 | Objects: Animals; Mice; Mice-Knockout; Disease Models- Animal |

| Contents/Mechanisms: Aorta; Apolipoproteins E | |

| Main outcome variables: Atherosclerosis |

Table 8.

Four high-frequent topics in the research of particulate matter and atherosclerosis

| Topics | Cluster | Explained variation, % |

|---|---|---|

| Topic 1. Epidemiological studies on the associations between tobacco exposure and atherosclerosis | Clusters 1, 3, and 9 | 3.5, 10.67, 4.44 |

| Topic 2. Epidemiological studies on the associations between environmental particulate matter exposure and atherosclerosis | Clusters 2 and 4 | 24.44, 1.33 |

| Topic 3. studies on the different roles of particulate matter size/components/source in health effects | Clusters 6 and 10 | 35.11, 7.11 |

| Topic 4. Toxicological studies on particulate matter-induced arteriosclerosis | Clusters 5, 7, and 8 | 6.67, 2.67, 3.11 |

Discussion

Topic 1 (Clusters 1, 3, and 9) included epidemiological studies on the associations between tobacco exposure and atherosclerosis. It is well-known that smoking is an important source of indoor air PM pollution [16] and levels of PM2.5 is a marker for secondhand tobacco smoke (SHS) [17]. Both active smoking and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) were associated with the progression of atherosclerosis [18, 19]. Cigarette smoking is a powerful risk factor for atherosclerotic diseases in middle-aged and aged populations [20–22]. Moreover, smoking is associated with lipoprotein abnormalities, which promote arterial lipid accumulation and atherogenesis [23–26]. SHS exposure or the inhalation of ETS is an independent risk factor for subclinical coronary atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease (CHD) and peripheral arterial disease (PAD). In addition, long-term exposure to SHS creates an imbalance in the lipid profile. This imbalance leads to lipid accumulation in the blood vessels of the heart and aorta in experimental models of human conditions in vivo, which in turn leads to atherosclerotic plaque formation [27]. In this topic, the association between familial and fetal tobacco smoke exposures and vascular damage also received close attention, because young adults/children/infants are at high risk of SHS exposure (Cluster 9). These studies show that thicker common carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) in young adulthood is associated with fetal tobacco smoke exposure [28–30]. Exposure to ETS is independently associated with decreased brachial artery flow-mediated dilation, decreased aortic elastic properties and increased ApoB levels among adolescents with increased cotinine level (a sensitive and specific biomarker of ETS exposure) [29, 31, 32]. Moreover, smoke-free legislation is associated with lower risk of smoking-related cardiac and cerebrovascular diseases [33–35].

Topic 2 (Clusters 2 and 4) covered epidemiological studies on the associations between environmental PM exposures and atherosclerosis. Epidemiological findings show a clear association between long-term exposure to PM2.5/PM10 and atherosclerosis. The studies reviewed on this topic focused on the effects of PM air pollution on subclinical atherosclerosis by means of noninvasive imaging (a predictor of cardiovascular events). Long-term PM concentrations are associated with increased CIMT progression [36–39], but does not appear to be associated with greater arterial stiffness [40]. CIMT, a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis, is associated with atherosclerosis development and progression in middle-aged populations [41]. The investigation of links between PM exposures and subclinical atherosclerosis mostly adopts the cohort and cross-sectional studies. The most studied cohort is the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) conducted across six study sites in the USA [36, 38, 40, 42]. In addition, exposure to traffic is also associated with atherosclerosis [43].

Topic 3 (Clusters 6 and 10) included studies on the different roles of PM components/sources in health effects. On this topic, the source that has the most concern is vehicle emissions (Cluster 10), which is linked with heart rate variability (HRV) [44], cardiac repolarization [45] and endothelial gene regulation [46]. The sources of PM from fire/combustion emission are also issues of concern. Exposure to ultrafine particles during fire suppression is considered a potential contributing factor for CHD [47]. Combustion emissions cause pro-atherosclerotic responses in ApoE−/− mice [48]. Moreover, these components (carbon black, metals, etc.) deserve closer attention. Nano-sized carbon black particles are associated with modest vasomotor impairment [49]. The zinc metal component of PM drives cardiovascular health effects, as well as the possible susceptibility induced by hyperlipidemia [50]. In addition, other air pollutants (nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, etc.) may also induce cardiovascular risk on their own, or combined with PM exposure. Elevated concentrations of PM and nitrogen dioxide increase the risk of supraventricular runs, as well as the number of ventricular runs [51].

Topic 4 (Clusters 5, 7, and 8) included toxicological studies on PM-induced arteriosclerosis. Mice, mice-knockout and disease model animals were chosen as study subjects for animal experiments (Cluster 8). ApoE−/− mice, which is probably of more concern, lacks apolipoprotein E, a high-affinity ligand for lipoprotein receptors, and develops atherosclerotic plaques in a fashion similar to humans [52]. In ApoE−/− mice, exposure to both ambient PM and tobacco smoke increased the plaque area in the pathological analysis of the aorta [6, 53–56]. Vascular endothelial cells were chosen as study subjects to explore molecular biology mechanisms (Cluster 5). On this topic, the induction of oxidative stress [57, 58] and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage [53, 59, 60] play a key role in the progression of atherosclerosis (Cluster 7).

Conclusions

Increasing attention has been given to the research field of PM and atherosclerosis. The number of published articles has increased from five for the period 1973–1978 to 89 for the period 2009–2014. The characteristics of the research literature in the fields of PM and atherosclerosis can be obtained through the quantitative analysis of bibliographic information and MeSH terms. Bibliographic information includes annual publications, authors, journals, institutions and countries; which can support a deeper understanding of research directions in the future. Cluster analysis by MeSH terms can provide clues that suggest popular topics in these fields, and help determine research emphases and priorities. Based on the quantitative analysis of bibliographic information and MeSH terms, we found that “tobacco smoke pollution” and “smoke and air particulate matter” were the most studied targets in the research field of PM and atherosclerosis.

It should be pointed out that the overall characteristics of these studies might be affected to a certain extent by the interest and funding of the researchers. In conclusion, the bibliometric analysis method is an effective approach for providing the characterization of a given research field, and can be adopted by other research fields as well.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (Grant No. 21507122).

Abbreviations

- CVD

cardiovascular diseases

- PM

particulate matter

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

WFF: performed the data analyses and wrote the manuscript; JXF: significantly contributed to the analysis and preparation of the manuscript; WXL and ZYD: helped perform the analysis with constructive discussions. HWD: contributed to the conception of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Feifei Wang, Email: wangff@craes.org.cn.

Xiaofeng Jia, Email: jia.xiaofeng@imicams.ac.cn.

Xianliang Wang, Email: xlwang@craes.org.cn.

Yongdong Zhao, Email: zhaoyongdongdong@126.com.

Weidong Hao, Phone: +86 10 82802352, Email: whao@bjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Jia X, Guo X, Li H, An X, Zhao Y. Characteristics and popular topics of latest researches into the effects of air particulate matter on cardiovascular system by bibliometric analysis. Inhal Toxicol. 2013;25(4):211–8. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2013.775196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pope CA, Burnett RT, Thurston GD, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Godleski JJ. Cardiovascular mortality and long-term exposure to particulate air pollution: epidemiological evidence of general pathophysiological pathways of disease. Circulation. 2004;109(1):71–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108927.80044.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun Q, Hong X, Wold LE. Cardiovascular effects of ambient particulate air pollution exposure. Circulation. 2010;121(25):2755–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.893461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araujo JA, Barajas B, Kleinman M, Wang X, Bennett BJ, Gong KW, et al. Ambient particulate pollutants in the ultrafine range promote early atherosclerosis and systemic oxidative stress. Circ Res. 2008;102(5):589–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brocato J, Sun H, Shamy M, Kluz T, Alghamdi MA, Khoder MI, et al. Particulate matter from Saudi Arabia induces genes involved in inflammation, metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2014;77(13):751–66. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2014.892446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen T, Jia G, Wei Y, Li J. Beijing ambient particle exposure accelerates atherosclerosis in ApoE knockout mice. Toxicol Lett. 2013;223(2):146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fetterman JL, Pompilius M, Westbrook DG, Uyeminami D, Brown J, Pinkerton KE, et al. Developmental exposure to second-hand smoke increases adult atherogenesis and alters mitochondrial DNA copy number and deletions in apoE(−/−) mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu HZ, Wang MH, Ho YS. Mapping of drinking water research: a bibliometric analysis of research output during 1992–2011. Sci Total Environ. 2013;443:757–65. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmadi M, Habibi S, Sedghi S, Hosseini F. Bibliometric analysis of stem cell publications in iran. Acta Inform Med. 2014;22(4):259–62. doi: 10.5455/aim.2014.22.259-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colantonio LD, Baldridge AS, Huffman MD, Bloomfield GS, Prabhakaran D. Cardiovascular research publications from Latin america between 1999 and 2008. A Bibliometric Study Arq Bras Cardiol. 2015;104(1):5–14. doi: 10.5935/abc.20140213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mansour AM, Mollayess GE, Habib R, Arabi A, Medawar WA. Bibliometric trends in ophthalmology 1997–2009. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63(1):54–8. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.151471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu C, Liu Z, Zhu F, Li S, Jiang L. A meta-analysis: is low-dose computed tomography a superior method for risky lung cancers screening population? Clin Respir J. 2014. doi:10.1111/crj.12222. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ginsparg P. ArXiv at 20. Nature. 2011;476(7359):145–7. doi: 10.1038/476145a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sewell W. Medical subject headings in medlars. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1964;52:164–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman LC. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc Networks. 1979;1(3):215–39. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saade G, Seidenberg AB, Rees VW, Otrock Z, Connolly GN. Indoor secondhand tobacco smoke emission levels in six Lebanese cities. Tob Control. 2010;19(2):138–42. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.030460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Deusen A, Hyland A, Travers MJ, Wang C, Higbee C, King BA, et al. Secondhand smoke and particulate matter exposure in the home. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2009;11(6):635–41. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard DJ, Ota RB, Briggs LA, Hampton M, Pritsos CA. Environmental tobacco smoke in the workplace induces oxidative stress in employees, including increased production of 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1998;7(2):141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiechl S, Werner P, Egger G, Oberhollenzer F, Mayr M, Xu Q, et al. Active and passive smoking, chronic infections, and the risk of carotid atherosclerosis prospective results from the Bruneck Study. Stroke. 2002;33(9):2170–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000027209.59821.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salonen R, Salonen JT. Determinants of carotid intima‐media thickness: a population‐based ultrasonography study in eastern Finnish men. J Intern Med. 1991;229(3):225–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1991.tb00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tell GS, Polak JF, Ward BJ, Kittner SJ, Savage PJ, Robbins J. Relation of smoking with carotid artery wall thickness and stenosis in older adults. The cardiovascular health study. The cardiovascular health study (CHS) collaborative research group. Circulation. 1994;90(6):2905–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.6.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willeit J, Kiechl S, Oberhollenzer F, Rungger G, Egger G, Bonora E, et al. Distinct risk profiles of early and advanced atherosclerosis prospective results from the bruneck study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(2):529–37. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.20.2.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu L, Mackay DF, Pell JP. Association between level of exposure to secondhand smoke and peripheral arterial disease: cross-sectional study of 5,686 never smokers. Atherosclerosis. 2013;229(2):273–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peinemann F, Moebus S, Dragano N, Möhlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Zeeb H, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure and coronary artery calcification among nonsmoking participants of a population-based cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(11):1556–61. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prugger C, Wellmann J, Heidrich J, De Bacquer D, Perier M-C, Empana J-P, et al. Passive smoking and smoking cessation among patients with coronary heart disease across Europe: results from the EUROASPIRE III survey. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(9):590–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yankelevitz DF, Henschke CI, Yip R, Boffetta P, Shemesh J, Cham MD, et al. Second-hand tobacco smoke in never smokers is a significant risk factor for coronary artery calcification. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2013;6(6):651–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan H, Wong LS, Bhattacharya M, Ma C, Zafarani M, Yao M, et al. The effects of second-hand smoke on biological processes important in atherogenesis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2007;7(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geerts CC, Bots ML, Grobbee DE, Uiterwaal CS. Parental smoking and vascular damage in young adult offspring: is early life exposure critical? The atherosclerosis risk in young adults study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(12):2296–302. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.173229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kallio K, Jokinen E, Raitakari OT, Hämäläinen M, Siltala M, Volanen I, et al. Tobacco smoke exposure is associated with attenuated endothelial function in 11-year-old healthy children. Circulation. 2007;115(25):3205–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.674804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matturri L, Ottaviani G, Corti G, Lavezzi AM. Pathogenesis of early atherosclerotic lesions in infants. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2004;200(5):403–10. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benowitz NL. Biomarkers of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(Suppl 2):349. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kallio K, Jokinen E, Saarinen M, Hämäläinen M, Volanen I, Kaitosaari T, et al. Arterial intima-media thickness, endothelial function, and apolipoproteins in adolescents frequently exposed to tobacco smoke. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2010;3(2):196–203. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.857771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonetti PO, Trachsel LD, Kuhn MU, Schulzki T, Erne P, Radovanovic D, et al. Incidence of acute myocardial infarction after implementation of a public smoking ban in Graubunden Switzerland: two year follow-up. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13206. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herman PM, Walsh ME. Hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, and asthma after implementation of Arizona’s comprehensive statewide smoking ban. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(3):491–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.179572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan CE, Glantz SA. Association between smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for cardiac, cerebrovascular, and respiratory diseases a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2012;126(18):2177–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.121301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adar SD, Sheppard L, Vedal S, Polak JF, Sampson PD, Diez Roux AV, et al. Fine particulate air pollution and the progression of carotid intima-medial thickness: a prospective cohort study from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis and air pollution. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):e1001430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauer M, Moebus S, Möhlenkamp S, Dragano N, Nonnemacher M, Fuchsluger M, et al. Urban particulate matter air pollution is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis: results from the HNR (Heinz Nixdorf Recall) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(22):1803–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun M, Kaufman JD, Kim SY, Larson TV, Gould TR, Polak JF, et al. Particulate matter components and subclinical atherosclerosis: common approaches to estimating exposure in a multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis cross-sectional study. Environ Health. 2013;12:39. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tonne C, Yanosky JD, Beevers S, Wilkinson P, Kelly FJ. PM mass concentration and PM oxidative potential in relation to carotid intima-media thickness. Epidemiology. 2012;23(3):486–94. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31824e613e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Neill MS, Diez-Roux AV, Auchincloss AH, Shen M, Lima JA, Polak JF, et al. Long-term exposure to airborne particles and arterial stiffness: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis(MESA) Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(6):844–51. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernández-Ortiz A, Jiménez-Borreguero LJ, Peñalvo JL, Ordovás JM, Mocoroa A, Fernández-Friera L, et al. The progression and early detection of subclinical atherosclerosis (PESA) study: rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2013;166(6):990–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen RW, Adar SD, Avol E, Cohen M, Curl CL, Larson T, et al. Modeling the residential infiltration of outdoor PM2. 5 in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis and air pollution (MESA Air) Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(6):824. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffmann B, Moebus S, Kröger K, Stang A, Möhlenkamp S, Dragano N, et al. Residential exposure to urban Air pollution, ankle–brachial index, and peripheral arterial disease. Epidemiology. 2009;20(2):280–8. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181961ac2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zanobetti A, Gold DR, Stone PH, Suh HH, Schwartz J, Coull BA, et al. Reduction in heart rate variability with traffic and air pollution in patients with coronary artery disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(3):324–30. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campen MJ, McDonald JD, Reed MD, Seagrave JC. Fresh gasoline emissions, not paved road dust, alter cardiac repolarization in ApoE−/− mice. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2006;6(3–4):199–209. doi: 10.1385/CT:6:3:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maresh JG, Campen MJ, Reed MD, Darrow AL, Shohet RV. Hypercholesterolemia potentiates aortic endothelial response to inhaled diesel exhaust. Inhal Toxicol. 2011;23(1):1–10. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.535572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baxter CS, Ross CS, Fabian T, Borgerson JL, Shawon J, Gandhi PD, et al. Ultrafine particle exposure during fire suppression-is it an important contributory factor for coronary heart disease in firefighters? J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(8):791–6. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181ed2c6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seilkop SK, Campen MJ, Lund AK, McDonald JD, Mauderly JL. Identification of chemical components of combustion emissions that affect pro-atherosclerotic vascular responses in mice. Inhal Toxicol. 2012;24(5):270–87. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2012.667455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vesterdal LK, Folkmann JK, Jacobsen NR, Sheykhzade M, Wallin H, Loft S, et al. Pulmonary exposure to carbon black nanoparticles and vascular effects. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.LaGier AJ, Manzo ND, Carll AP, Jaskot RH, Slade R, Richards JH, et al. A hyperlipidemic rabbit model provides new insights into pulmonary zinc exposure effects on cardiovascular health. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2008;8(4):195–206. doi: 10.1007/s12012-008-9028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berger A, Zareba W, Schneider A, Rückerl R, Ibald-Mulli A, Cyrys J, et al. Runs of ventricular and supraventricular tachycardia triggered by air pollution in patients with coronary heart disease. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48(11):1149–58. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000245921.15916.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reddick RL, Zhang SH, Maeda N. Atherosclerosis in mice lacking apo E. Evaluation of lesional development and progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1994;14(1):141–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.14.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knight-Lozano CA, Young CG, Burow DL, Hu ZY, Uyeminami D, Pinkerton KE, et al. Cigarette smoke exposure and hypercholesterolemia increase mitochondrial damage in cardiovascular tissues. Circulation. 2002;105(7):849–54. doi: 10.1161/hc0702.103977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun Q, Yue P, Deiuliis JA, Lumeng CN, Kampfrath T, Mikolaj MB, et al. Ambient air pollution exaggerates adipose inflammation and insulin resistance in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. Circulation. 2009;119(4):538–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.799015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wan Q, Cui X, Shao J, Zhou F, Jia Y, Sun X, et al. Beijing ambient particle exposure accelerates atherosclerosis in ApoE knockout mice by upregulating visfatin expression. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2014;19(5):715–24. doi: 10.1007/s12192-014-0499-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang Z, Harrison CM, Chuang GC, Ballinger SW. The role of tobacco smoke induced mitochondrial damage in vascular dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Mutat. Res., Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2007;621(1):61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kunitomo M, Yamaguchi Y, Kagota S, Yoshikawa N, Nakamura K, Shinozuka K. Biochemical evidence of atherosclerosis progression mediated by increased oxidative stress in apolipoprotein E-deficient spontaneously hyperlipidemic mice exposed to chronic cigarette smoke. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;110(3):354–61. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09100FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wei H, Wei D, Yi S, Zhang F, Ding W. Oxidative stress induced by urban fine particles in cultured EA. hy926 cells. Human & experimental toxicology. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Ballinger SW, Patterson C, Knight-Lozano CA, Burow DL, Conklin CA, Hu Z, et al. Mitochondrial integrity and function in atherogenesis. Circulation. 2002;106(5):544–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000023921.93743.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang Z, Knight CA, Mamerow MM, Vickers K, Penn A, Postlethwait EM, et al. Prenatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure promotes adult atherogenesis and mitochondrial damage in apolipoprotein E−/− mice fed a chow diet. Circulation. 2004;110(24):3715–20. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000149747.82157.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]