Abstract

Successful valorisation of raspberry and blueberry pomace was achieved through their application, as dried and ground powders, in the formulation of value-added gluten-free cookies. Simplex-lattice mixture design approach was applied to obtain the product with the best sensory properties, nutritional profile and antioxidant activity. The highest desirability of 90.0 % was accomplished with the substitution of gluten-free flour mixture with 28.2 % of blueberry and 1.8 % of raspberry pomace. The model was verified. Optimized cookies had similar protein (3.72 %) and carbohydrate (66.7 %) contents as gluten-containing counterparts used for comparison, but significantly lower fat content (10.97 %). Daily portion of the optimized cookies meets: 5.00 % and 7.73 % of dietary reference intakes (DRIs) for linoleic acid, 23.6 % and 34.3 % of DRIs for α-linolenic acid and 10.3 % and 15.6 % of DRIs for dietary fibers, for male and female adults, respectively. The nutritional profile of the optimized formulation makes it comparable with added-value gluten-containing counterparts.

Keywords: Gluten-free cookies, Raspberry, Blueberry, Pomace, Mixture design

Introduction

Celiac disease is one of the most common lifelong disorders with a prevalence of approximately 1 % in world population (Gujral et al. 2012). Adherence to a strict gluten-free diet leads to significantly lower intake of vitamins, dietary fibers, iron and calcium (Hallert et al. 2002; Hopman et al. 2006; Thompson et al. 2005). Gluten-free diet is also characterized by low daily energy intake and unbalanced composition of macronutrients compared to that of normal, balanced diet (Bardella et al. 2000). Hence, complete, lifelong avoidance of gluten could be a problem regarding the quality of the available products. Their structure, taste, and appearance are still different from their gluten-containing counterparts.

The most commonly used ingredients of gluten-free cereal products are gluten-free flours, corn, rice, potato and tapioca starches and different hydrocolloids able to mimic the viscoelastic properties of gluten. Recent studies conducted with the aim of improving the nutritional profile of gluten-free products have mainly been focused on the use of pseudocereals as functional gluten-free ingredients (Islas-Rubio et al. 2014; Sakač et al. 2010; Sedej et al. 2011).

An increasing trend in fruit waste revalorization is mainly attributed to the high amount of valuable bioactive compounds remained in by-products after fruit processing. Fruit juice industry generates a considerable amount of waste which may account up to 20 % of the initial fruit weight (Khanal et al. 2009). In addition to their good nutritional and functional properties, by-products from fruit industry also have the advantage of being gluten free, making them potentially ideal ingredients for creating new food products for celiac patients. However, only few studies investigated a possibility of enrichment of gluten-free products using waste from fruit processing industry, such as mango peel powder (Ajila et al. 2008). defatted strawberry and blackcurrant seeds (Korus et al. 2011). orange pomace (O’Shea et al. 2015) and apple skin powder (Rupasinghe et al. 2008).

Raspberry pomace, by-product from juice industry, has been reported as a good source of dietary fibers (Górecka et al. 2010) and phenolic compounds (Bobinaitė et al. 2013). Četojević-Simin et al. (2015) reported strong antioxidant, antiproliferative and proapoptotic activity of raspberry pomace extracts. Due to unique composition of raspberry seed oil, characterized by high tocopherol and α-linolenic acid content Parry and Yu (2004). raspberry pomace could also be beneficial in prevention of coronary heart diseases.

Blueberries are a rich source of anthocyanins and other phenolic compounds with documented health promoting effects (Prior et al. 1998). By-products generated during blueberry fruit processing into juice exhibit strong antioxidant activity (Lee and Wrolstad 2004). Pomace contains up to 50 % of the procyanindins present in the fresh fruit (Khanal et al. 2009). Studies regarding potential application of blueberry pomace have mainly been focused on extruded products (Khanal et al. 2009) and spray-dried encapsulated extract powder (Flores et al. 2014).

Concerning the above mentioned health benefits, raspberry and blueberry pomace were dried and ground to obtain new food ingredients, with the aim of improving the nutritional profile and antioxidant capacity of gluten-free cookies. In order to optimize the ingredients proportion and to create a new value-added product, simplex-lattice mixture design approach was used with two main goals: enhancement of nutritional and sensory quality. In order to evaluate the effects of pomace addition, the nutritional profile of the optimized cookie was compared with the nutritional value of commercially available whole grain counterparts.

Materials and methods

Materials

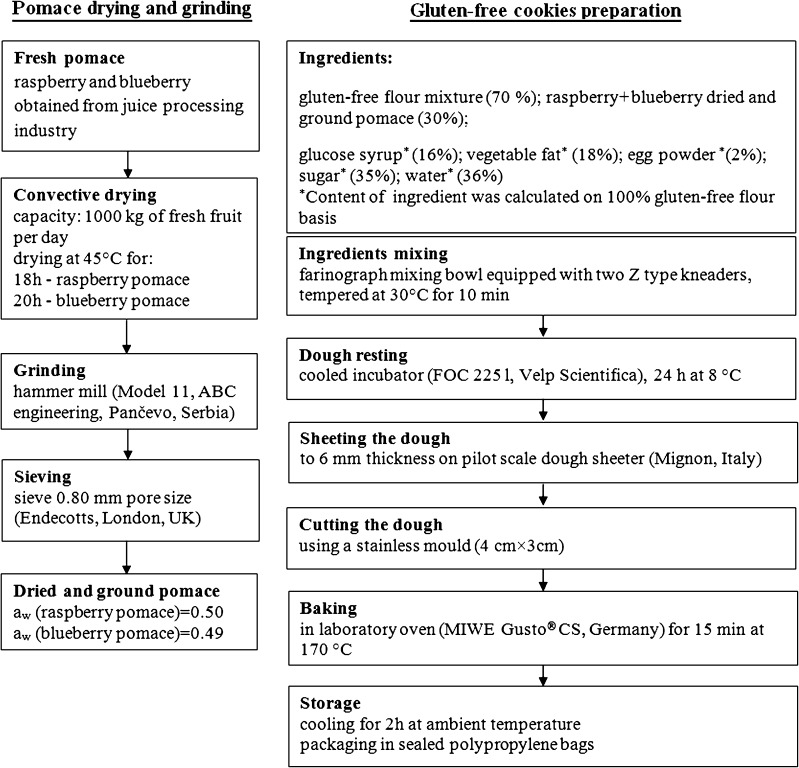

Fresh raspberry and blueberry pomace were obtained as by-products from the juice processing industries („Bio Una“, Novi Sad, Serbia and “Zdravo Organic”, Selenča, Serbia). After drying and grinding according to the procedure given in Fig. 1 the fractions passing through the 0.80 mm sieve were used as ingredients in cookies formulation. Commercially available gluten-free flour mixture consisting of corn starch/flour, potato starch/flour, rice flour, guar gum, baking powder and salt was obtained from “Nutri allergy center”, Zemun, Serbia. Vegetable fat, egg powder, sugar and glucose syrup were commercially available.

Fig. 1.

Process flow chart of pomace and cookie preparation

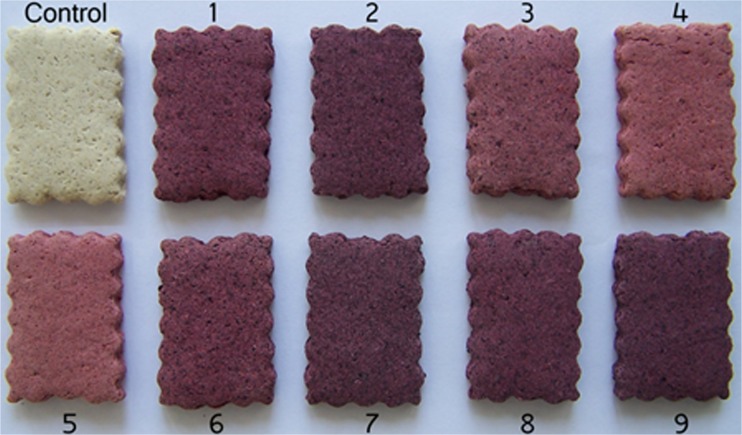

Cookie preparation

Phases of cookies preparation are given in Fig. 1. The basic formulation of cookies (control) consisted of gluten-free flour mixture, glucose syrup, vegetable fat, egg powder and water. All other cookie formulations were obtained by substituting of 30 % (w/w) of gluten-free flour mixture with different ratios (Table 1) of raspberry and blueberry pomace. The image of control and cookies containing raspberry and blueberry pomace is given in Fig. 2. All determined parameters were obtained from three independent batches of cookies and the average values were calculated for all formulations.

Table 1.

Response values for control cookies (C) and cookies containing pomace: raspberry (RP) and blueberry (BP)

| Ingredient proportion (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP | BP | ΔE | H | OSQ | TPC | ACY | IC50 | M | aw | |

| 1 | 15 | 15 | 4.74b

(0.03) |

1018.4c

(13.27) |

4.31a

(0.01) |

320.1c

(21.45) |

156.2c

(14.54) |

4.73b,c,d

(0.21) |

6.70b

(0.03) |

0.48a

(0.00) |

| 2 | 0 | 30 | 1.63a

(0.04) |

1402.3b

(2.12) |

4.33a

(0.00) |

481.0a

(11.99) |

260.7a

(2.36) |

4.05a

(0.08) |

6.47a

(0.02) |

0.47a

(0.00) |

| 3 | 22.5 | 7.5 | 6.02e

(0.04) |

940.0a

(46.70) |

4.15b

(0.00) |

215.5d

(4.48) |

98.3d

(5.93) |

4.90b,c

(0.14) |

7.16d

(0.05) |

0.54d

(0.00) |

| 4 | 30 | 0 | 7.62c

(0.04) |

938.4a

(11.59) |

4.26a

(0.01) |

145.5b

(5.43) |

43.4b

(2.31) |

5.07b,c

(0.04) |

7.90c

(0.02) |

0.61b

(0.00) |

| 5 | 30 | 0 | 7.69c

(0.05) |

940.3a

(10.12) |

4.27a

(0.01) |

140.5b

(10.93) |

40.9b

(0.07) |

5.08c

(0.00) |

7.92c

(0.09) |

0.62b

(0.00) |

| 6 | 15 | 15 | 4.68b

(0.03) |

1020.4c

(9.25) |

4.31a

(0.03) |

311.0c

(12.96) |

150.7c

(1.54) |

4.60b,d

(0.04) |

6.67b

(0.02) |

0.49c

(0.00) |

| 7 | 0 | 30 | 1.59a

(0.02) |

1410.0b

(2.91) |

4.34a

(0.01) |

487.7a

(18.54) |

250.0a

(4.01) |

3.97a

(0.01) |

6.48a

(0.01) |

0.48a

(0.00) |

| 8 | 7.5 | 22.5 | 2.99d

(0.01) |

1170.6d

(5.61) |

4.49c

(0.00) |

400.1e

(11.12) |

212.5e

(1.58) |

4.36a,d

(0.25) |

6.46a

(0.01) |

0.48d

(0.00) |

| 9 | 0 | 30 | 1.50a

(0.02) |

1398.9b

(11.46) |

4.34a

(0.01) |

489.1a

(10.03) |

257.2a

(1.44) |

3.96a

(0.03) |

6.48a

(0.02) |

0.48a

(0.00) |

| C | 0 | 0 | 1.33 (0.04) |

576.2 (35.89) |

3.85 (0.03) |

0.20 (0.01) |

ND | 153.1 (0.64) |

6.43 (0.02) |

0.48 (0.00) |

ΔE–color differences among cookies; H (g)–hardness; OSQ–overall sensory quality; TPC (mg/100 g DM)–total phenolic content; ACY (mg/100 g DM)–total monomeric anthocyanins content; IC50 (DPPH·) (mg/ml)–IC50 values for DPPH∙ scavenging activity; M (%)-moisture content; aw–water activity

Each value is the mean of three independent experiments. Standard deviations are given in parentheses. For samples 1–9 means followed by different superscript letters in the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Fig. 2.

Images of control and gluten-free cookies containing raspberry and blueberry pomace

Experimental design

Optimal content of raspberry and blueberry pomace in gluten-free cookies formulation was determined using simplex-lattice two component mixture design. Preliminary study based on sensory analysis was conducted in order to define constrains of independent variables. Substitution of 30 % (w/w) of gluten-free flour mixture with raspberry/blueberry pomace was found to be maximal, regarding the sensory acceptance and textural characteristic of the final product. The experimental design was generated using Design-Expert 7.0 software (Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, USA). Numerical optimization of cookie formulation was based on generating the solution (proportion of blueberry and raspberry pomace) with the best sensory properties, the highest polyphenolic content and color stability of the final product. The measurements of all responses (dependent variables) were carried out in triplicate and given as average value with standard deviation.

Color parameters

Color measurement of the top surface of each cookie formulation was carried out on 10 randomly selected samples using a chromameter Minolta, CR-400 (Minolta Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Color measurements were taken in five areas of cookie (center and corners) and the results were given according to the CIELab color system as mean values: L* describing lightness (L* = 0 for black, L* = 100 for white), a* describing intensity in green-red (a* < 0 for green, a* > 0 for red), and b* describing intensity in blue-yellow (b* < 0 for blue, b* > 0 for yellow). Color measurements were performed 24 h after baking as well as after six months of storage during which cookies were kept in dark in sealed polypropylene bags at ambient temperature. Color differences were calculated according to the following equation:

where L*2, a*2 and b*2 represents the values of measured color parameters after 6 months of storage, while L*1, a*1 and b*1 represents the values of these parameters 24 h after baking.

According to ΔE value, color differences were categorized as: imperceptible (0–0.5), slightly noticeable (0.5–1.5), noticeable (1.5–3.0), significantly noticeable (3.0–6.0), extremely noticeable (6.0–12.0) and colors of different shades (above 12.0) (Popov-Raljić et al. 2013).

Textural analysis

Textural analysis of the cookies was conducted using a TA.XTPlus Texture Analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, England, UK), equipped with a 3-point bending rig (HDP/3 PB), and a 30 kg load cell. Texture analyzer settings were: mode – measure force in compression; pre-test speed – 1.0 mm/s; test speed – 3.0 mm/s; post-test speed – 10.0 mm/s; distance – 5.0 mm; trigger force – 50 g. Cookie hardness defined as maximal force at the point of the break was determined 24 h after baking. Five measurements per each sample were performed.

Sensory analysis

Sensory evaluation was performed 24 h after baking by seven experienced trained assessors (four females and three males) aged between 35 and 50 years. The samples were served in randomized order generated using XLSTAT software (Addinsoft, New York, USA), and coded with random three-digit numbers. Drinking water was provided for the palate cleansing between two samples. The evaluation was performed in individual booths featuring controlled lighting and positive air pressure.

The sensory attributes identified as the most important descriptors of gluten-free cookies enriched with raspberry/blueberry pomace were: appearance-AP (shape, color, surface characteristics, and the presence of particles), hardness of cookie at first bite-SH, mouthfeel-MTF (chewiness, separation of particles, and adhesiveness), odor-O, taste-T and flavor-F. Scoring procedure based on the five-point scale was adopted from previous studies used for the assessment of cookies and similar confectionery products (Pestorić et al. 2014; Sedej et al. 2011). Since selected properties do not contribute equally to the overall sensory quality of a product, the importance coefficients (ICs) for each sensory property were defined by the assessors: 1 for appearance; 1.5 for hardness of cookie at first bite; 2 for mouthfeel; 1.5 for odor; 1.5 for taste and 2.5 for flavor. The obtained scores for six evaluated properties were averaged and used as a measure of overall sensory quality of the product. Based on the total score, the quality of the cookies was categorized as follows: unacceptable quality (< 2.5), good quality (2.5–3.5), very good quality (3.5–4.5), excellent quality (> 4.5).

Determination of antioxidant activity

Extraction procedure

Determination of total phenolic content and DPPH• scavenging activity was performed on cookies extracts prepared according to procedure of Larrauri et al. (1997). Briefly, 10 g of samples was extracted sequentially with 40 mL of methanol:water (50:50, v:v) and 40 mL of acetone: water (70:30, v:v) at room temperature for 60 min. After centrifugation at 2500 RPM for 15 min, combined supernatants were made up to 100 mL with distilled water.

The extracts for determination of total monomeric anthocyanins were prepared according to the procedure of De Brito et al. (2007) with the following modification: 1 % HCl in methanol was used for extraction and the results are expressed using corresponding molar absorptivity.

Total phenolic content

Total phenolic content of cookie extract was determined spectrophotometrically at 750 nm (Jenway, 6405 UV/Vis) by using Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent (Singleton et al. 1999) and the obtained results were expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE) (μg GAE/g of sample on wet mass basis).

DPPH•scavenging activity

Effect of different cookie extracts on scavenging of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radicals (DPPH•) was determined according to the method of Sedej et al. (2011). Results were expressed as the concentration (mg/mL) of the extract which reduce the initial DPPH• concentration to 50 % (IC50 value).

Total monomeric anthocyanins

Content of total monomeric anthocyanins was determined according to pH-differential method (Giusti and Wrolstad 2001) using UV-visible spectrophotometer (Jenway, 6405 UV/Vis). The obtained extracts were diluted in pH 1.0 and pH 4.5 buffers. The results are expressed as cyanidin-3-O-glucoside using molar absorptivity ε = 34,300 Lmol−1 cm−1.

Proximate composition

Proximate composition was analyzed using the methods of AOAC (2000). protein (Official Method No. 950.36), fat (Official Method No. 935.38), reducing sugar (Official Method No. 975.14), total dietary fiber (Official Method No. 958.29), starch (14.031), and moisture (Official Method No.926.5). The following parameters were determined in optimized and control cookies: protein content, fat content, reducing sugar and starch. The moisture content was determined in control and samples 1–9.

Water activity of cookies as well as of dried and ground pomace was determined using Testo 650 measuring instrument with a pressure-tight precision humidity probe (Testo AG, USA). Each result presents the average value of 3 measurements.

Nutritional characteristics of the optimized cookie

Fatty acid composition

Pressurized solvent extraction performed on Dionex ASE 350 system (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used for extraction of fat from control and optimized gluten-free cookies under the following conditions: solvent-hexane; oven temperature-90 °C; static time-10 min; static cycles- 2; purge time-30 s; rinse volume-30 %. Fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were prepared from the extracted lipids with boron trifluoride/methanol solution. Samples were analyzed by a GC Agilent 7890A system with FID according the method of Csengeri et al. (2013). Highly polar biscyanopropyl column specifically designed for detailed separation of cis/trans isomers of FAMEs Supelco SP-2560 (Capillary GC Column 100 m × 0.25 mm, d = 0.20 μm) was used. Helium was used as a carrier gas (purity 99.9997 vol%, flow rate = 1.26 ml/min). The fatty acids were identified by comparing their retention times with retention times of standard FAMEs solution. Calculation of total fatty acid content in 100 g of sample was done using conversion factors (MAFF 1998).

Determination of mineral composition

Calcium and iron content of the control and optimized gluten-free cookies were determined after dry ashing, according to the procedure of Pavlović et al. (2001) using Varian Spectra AA 10 (Varian Techtron Pty Limited, Mulgrave Victoria, Australia) atomic absorption spectrophotometer equipped with a background correction (D2-lamp).

Statistical analysis

The significant differences for each parameter among cookie samples were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). Principal component analysis (PCA) was used as a tool for discriminate and differentiate the data obtained from sensory analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using XLSTAT software.

Results and discussion

Color of the cookies

The color of cookies as an important factor affecting consumers acceptance was determined instrumentally by comparing L*, a* and b*values with those of control cookies. Substitution of 30 % of gluten-free flour mixture with different proportion of raspberry and blueberry pomace led to increase in cookies darkness and redness and decrease in yellowness (data not shown). The increase of blueberry pomace content in cookie formulation led to decrease in b*values, indicating the presence of characteristic blue anthocyanins such as 3-glycosidic derivatives of delphinidin, malvidin and petunidin (Routray and Orsat 2011). Addition of raspberry pomace in formulation increased the redness of cookies, due to the presence of characteristic red pigment cyaniding-3-sophoroside (Chen et al. 2007). Changes in the cookies color reflected the composition of present anthocyanins in the pomace.

Significant negative correlation (P < 0.05) was observed between total monomeric anthocyanins content and color parameters of the cookies. Pearson’s correlation coefficients for L*, a* and b* values were −0.9524, −0.9891 and −0.9369, respectively. Similar findings regarding the correlation of anthocyanins level and color parameters were observed in different cherry cultivars by Gonçalves et al. (2006).

Although fruit concentrates rich in anthocyanins can successfully be used as natural food colorants, their application is limited because of their low stability and color changes which could affect the consumers acceptance of the final product. Therefore, the color was measured after six months of storage in polypropylene bags at ambient temperature in the dark, thus imitating the storage conditions of the cookies available in the market. Color differences were given in terms of ΔE (Table 1) and minimization of this parameter was chosen as one of the criteria in the numerical optimization study. Extremely noticeable differences (ΔE = 6.0–12.0) in the color was observed in the cookies with higher amount of raspberry pomace (22.5 % and 30 % of substitution). Ochoa et al. (1999) also reported strong degradation of anthocyanin pigments from raspberry pulp after 50 days of storage at 37 °C. Cookies with blueberry pomace showed noticeable changes in color (ΔE = 1.5–3.0) during storage (ΔE mean value was 1.57) indicating higher stability of anthocyanins from blueberry in comparison to those from raspberry pomace.

Textural properties of cookies

Partial substitution of gluten-free flour mixture with raspberry and blueberry pomace contributed to significant increase in hardness of cookies in comparison to the control (Table 1). Since water and fat as the main ingredients associated with hardness of the product were added in the same amount in formulations 1–9, the differences in textural properties of cookies can be solely attributed to the content and functional properties of dietary fibers from the added pomace. Similar findings regarding impact of dietary fibers on textural properties of bakery products are reported in numerous studies (Elleuch et al. 2011).

The obtained results indicated significant (P < 0.05) negative correlation (−0.735) between textural properties and moisture content of cookies. Substitution of gluten-free flour mixture with raspberry pomace (samples 4, 5) resulted in the lowest value of hardness and the highest moisture content of cookies, probably due to high water retention during baking. On the contrary, cookies containing blueberry pomace (samples 2, 7, 9) had the highest value of hardness and the lowest moisture content.

Sensory properties of cookies

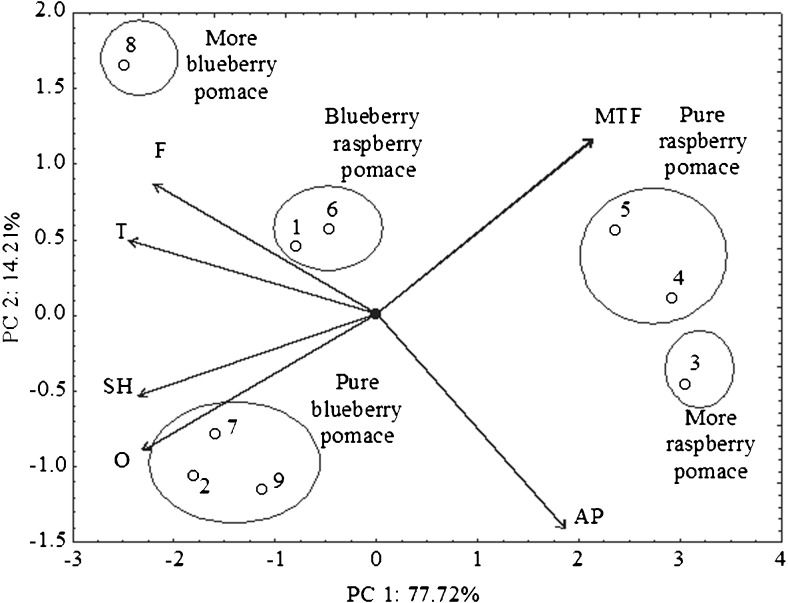

Although the overall sensory quality of control cookies can be considered as very good (3.85), the addition of pomace generally contributed to better sensory properties of this type of product. Overall sensory quality of different formulations of gluten-free cookies with raspberry and blueberry pomace was in the range from 4.15 to 4.49. Cookies in which gluten-free flour mixture was substituted with 22.5 % of blueberry and 7.5 % of raspberry pomace obtained the highest score regarding flavor and taste, contributing to significantly (P < 0.05) higher overall sensory quality (4.49) in comparison to other formulations. Principal component analysis of gluten-free cookie samples was performed on mean values of six sensory attributes aiming to identify similarities of their sensory profiles. Since the total variance of the sensory attributes based on the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) was 91.94 %, it could be considered as sufficient for data representation. The PCA graph given in Fig. 3 showed that PC1 was negatively affected by T (which contributed 20.19 % of total variance, based on correlations), SH (18.42 %), F (16.32 %) and O (18.30 %), while the positive influence on PC1 was observed by MTF (15.15 % of total variance, based on correlations) and AP (11.61 %). The second principal component, PC2, was positively affected by MTF (which contributed 26.03 % of total variance, based on correlations) and F (14.53 %), while the negative influence was noticed by O (14.60 %) and AP (35.28 %).

Fig. 3.

Biplot of six sensory attributes for gluten-free cookie samples with addition of raspberry and blueberry pomace

The position of nine cookie samples in the multivariate factor space of the first two PCs is given in Fig. 3. Scores were arranged in five areas and showed a clear separation between cookies containing raspberry and blueberry pomace. Cookies in which 30 % of gluten-free flour mixture was substituted with blueberry pomace (2, 7 and 9) tended to be negatively correlated to PC1, and negatively correlated to PC2, and were described as samples with the highest scores for O and SH. These cookies were also characterized by high score for T (4.51) and F (4.80). Cookies in which gluten-free flour mixture was substituted with 22.5 % of blueberry and 7.5 % of raspberry pomace (sample 8) was positioned in at the upper left side of the PCA plot as the sample with highest scores for F and T. The obtained results indicated that the addition of blueberry pomace in higher amount generally contributed to better taste, flavor, odor and textural properties of cookies in comparison to the corresponding formulations with raspberry pomace. Therefore, these sensory attributes could be considered as discriminating factors for cookies containing blueberry pomace as the dominant functional ingredient.

Cookies containing raspberry pomace as the dominant functional ingredient (samples 3, 4 and 5) were discriminated along PC1 according to AP and MTF. Appearance of cookies comprises visual properties including shape and surface characteristic and represents an important factor in consumer’s acceptance of novel food product. These sensory attributes are mainly related to the technological aspect of cookies preparation. Although addition of raspberry pomace in higher amount contribute to production of cookies with higher score for AP (≥4.80), shape and surface characteristics of cookies containing blueberry pomace are also highly scored by the assessors (4.65). The mouthfeel, as one of the multi-parameter sensory attributes, combines several sensory sensations such as adhesiveness, chewiness and separation of particles. Its evaluation in the mouth is a dynamic process, mainly related to the physicochemical properties of the product. The highest score regarding MTF (3.95) was observed for cookies containing only raspberry pomace (4 and 5). Among sensory attributes, MTF obtained lower scores for all cookie formulations due to residual (after swallowing) stickiness. Samples containing 15 % of each pomace (1 and 6) were located close to the origin of the graphic indicating their average scores for F, T, SH, O, MTF and AP, in comparison to the other samples.

Antioxidant properties of cookies

Total phenolic content (TPC), anthocyanins content (ACY) and DPPH∙ scavenging activity of cookies are presented in Table 1. Formulations containing only blueberry pomace were characterized with the highest TPC and ACY content. These parameters varied gradually and declined significantly with the increase in the raspberry pomace content of the sample. The average TPC was 6-fold higher in cookies containing only blueberry pomace in comparison to raspberry cookies. The average ACY was 1.6 times higher in the blueberry than in the raspberry pomace cookies. The differences in antioxidant properties of the examined cookies could be attributed to the difference in polyphenolic profiles and antioxidant potential of raspberry and blueberry. The obtained results are in accordance with the previous studies reporting higher TPC content of blueberry (261–585 mg/g) than of raspberry (99 mg/g) Nile and Park (2014). as well as 2-fold higher ACY content (Souza et al. 2014). Moreover, higher antioxidant potential of blueberry pomace could be attributed to its structure, mainly consisting of skin as the fruit part most abundant in anthocyanins. According to Lee and Wrolstad (2004). blueberry skin shows the highest antioxidant activity, ACY and TP content compared to other analysed berry parts.

Good correlation between TPC and DPPH∙, ACY and DPPH∙ (r = −0.987 and −0.980, respectively) observed in this study indicate that phenolic compounds, in this case anthocyanins present the major antioxidants. It should be pointed out that the difference in antioxidant activity between two formulations, containing only blueberry and raspberry pomace was 20 %. In comparison to the control cookie, TPC content and antioxidant activity of the samples containing pomace were significantly improved.

Regression equations and model analysis

Simplex-lattice mixture design approach was applied in order to examine the effects of raspberry (X1) and blueberry (X2) pomace addition on color, textural and sensory properties of gluten-free cookies, their antioxidant potential, moisture content and aw value. Model equations and parameters indicating their fitting to the experimental data are given in Table 2. Suitability of the regression models to accurately predict the variations for all responses is indicated by p-value lower than 0.05. Adequacy of the model was also evaluated using coefficient of determination (R2), adjusted coefficient of determination (R2adj), predicted coefficient of determination (R2pred) and lack-of fit p-value. Coefficient of determination (R2) is defined as proportion to the total sum of squares explained by the model (Joglekar and May 1987). All model equations from this study fit the experimental data with R2 values higher than 0.98, indicating their good fitness for interpolation the actual set of data (R2 > 0.80) (Joglekar and May 1987). The ability of the derived regression model to predict responses for new observations was given in terms of R2pred. The values of this model parameter were found to be in reasonable agreement with R2adj referring to the criteria that difference between these two parameters should not exceed 0.2 (Alao and Konneh 2009). Lack of fit p-values were higher than 0.05 for all responses indicating non-significant lack of fit at the 95 % confidence level and confirm the suitability of the model.

Table 2.

Regression equations and model adequacy parameters

| Predicted model equation | R2 | R2 adj | R2 pred | Regression p-value | Lack-of fit p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color parameters | ||||||

| ΔE | Y = 0.255X1 + 0.052X2 | 0.9989 | 0.9987 | 0.9984 | <0.0001 | 0.0968 |

| Texture | ||||||

| Hardness | Y = 31.310X1 + 46.755X2-0.678X1X2 | 0.9997 | 0.9996 | 0.9994 | <0.0001 | 0.8895 |

| Sensory properties | ||||||

| Overall acceptance | Y = 0.143X1 + 0.145X2-5.935*10−5X1X2-6.061*10−5X1X2(X1-X2) | 0.9958 | 0.9933 | 0.9770 | 0.0001 | 0.0644 |

| Antioxidant potential | ||||||

| TPC | Y = 4.671X1 + 16.199X2 | 0.9985 | 0.9983 | 0.9976 | <0.0001 | 0.2292 |

| ACY | Y = 1.385X1 + 8.619X2 + 0.0257X1X2 | 0.9982 | 0.9976 | 0.9962 | <0.0001 | 0.4600 |

| IC50 (DPPH·) | Y = 0.169X1 + 0.133X2 + 5.869*10−4X1X2 | 0.9924 | 0.9899 | 0.9835 | <0.0001 | 0.9992 |

| Moisture | Y = 0.263X1 + 0.216X2-2.260*10−3X1X2 | 0.9997 | 0.9996 | 0.9993 | <0.0001 | 0.6506 |

| aw | Y = 0.020X1 + 0.016X2-2.518*10−4X1X2 | 0.9884 | 0.9846 | 0.9745 | <0.0001 | 0.2606 |

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used in the most accurate model, to determine the statistical significance of the regression coefficients by conducting the Fisher’s F-test at 95 % confidence level. Linear model fit the best for the following responses: TPC and ΔE, while quadratic model adequately fitted for hardness, moisture, aw, ACY and IC50. Cubic model was found to be best for representing the experimental data of sensory properties of gluten-free cookies (Table 2).

Model optimization and verification

Numerical optimization was performed to find the proportion of raspberry and blueberry pomace which contribute to the best sensory properties, maximal TPC, ACY and minimal IC50 value of the final product. The secondary optimization objectives were: to achieve the highest product stability regarding microbiological spoilage (minimal aw value) as well as the highest color stability during the storage (minimal value of ΔE). The desirability function, as the most commonly used approach in multiple responses optimization studies, was conducted and the highest value of this parameter was chosen as the criteria for selection of optimal ingredients proportion. The highest desirability of 90.0 % was accomplished with the following ingredients proportion: 28.2 % of blueberry and 1.8 % of raspberry pomace. Since the final step in optimization study was to verify a model by predicting responses at the optimal settings, three independent set of experiments were performed using optimized cookies formulation. The obtained results for all responses were in agreement with the model predictions (Table 3) and within 95 % confidence interval (CI), thus indicated that the model was satisfactory and suitable.

Table 3.

Verification of the model using optimized cookie formulation

| Response | Obtained value | Prediction | 95 % CI low | 95 % CI high | 95 % PI low | 95 % PI high |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆E | 1.89 | 1.93 | 1.83 | 2.03 | 1.70 | 2.16 |

| Hardness | 1343.1 | 1341.9 | 1337.0 | 1346.8 | 1330.5 | 1353.2 |

| Overall sensory quality | 4.42 | 4.41 | 4.40 | 4.43 | 4.39 | 4.44 |

| ACY | 246.8 | 245.4 | 240.3 | 250.5 | 233.6 | 257.2 |

| TPC | 462.1 | 465.7 | 459.2 | 472.3 | 450.3 | 481.1 |

| IC50 (DPPH∙) | 4.05 | 4.09 | 4.03 | 4.14 | 3.96 | 4.21 |

| Moisture | 6.46 | 6.45 | 6.44 | 6.46 | 6.42 | 6.48 |

| aw | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.49 |

Optimized cookie can be considered as the product with high color stability, since noticeable changes (ΔE = 1.89 ± 0.05) were observed after six months of storage. Low aw value (0.47 ± 0.02) indicates its stability regarding microbial spoilage, which is of particular importance for the quality, safety and shelf life of the product. Sensory properties and antioxidant activity were highly improved by the addition of the optimized proportion of raspberry and blueberry pomace. Regarding the overall sensory quality, the final product can be categorized as very good (4.42 ± 0.02), with favorable taste and flavor.

Nutritional adequacy of the optimized cookies

With the aim to demonstrate the effect of pomace addition, the content of macronutrients (proteins, carbohydrate, fats, dietary fibers, essential fatty acids–linoleic and α-linolenic) and micronutrients (Ca and Fe) were determined in control and optimized cookies and their contributions to dietary reference intakes (DRIs) (NRC 1989) was calculated (Table 4). Moreover, to examine whether raspberry and blueberry pomace as functional ingredient could provide nutritional characteristics of gluten-free cookies similar to those of gluten-containing counterparts, they were compared with the nutritional value of commercially available whole grain cookies (n = 10) enriched with berry fruits labelled as “good source of fiber”.

Table 4.

Contribution of macronutrients and micronutrients intake to the recommended DRIsa based on average portion (50 g) of cookies consumption

| Gender | DRIsa (g/day) | Contribution to DRIs (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control cookie | Optimized cookie | |||

| Macronutrient (g/day) | ||||

| Proteins | Male | 56 | 1.96 | 3.32 |

| Female | 46 | 2.39 | 4.04 | |

| Carbohydrate | Male | 130 | 23.6 | 25.7 |

| Female | 130 | 23.6 | 25.7 | |

| Fat | Adults | 65 | 17.8 | 16.9 |

| Dietary fibers | Male | 38 | 0.20 | 10.3 |

| Female | 25 | 0.30 | 15.6 | |

| Linoleic acid (n-6) | Male | 17 | 2.68 | 5.00 |

| Female | 11 | 4.14 | 7.73 | |

| α-linolenic acid (n-3) | Male | 1.6 | 0.94 | 23.6 |

| Female | 1.1 | 1.36 | 34.3 | |

| Micronutrient (mg/day) | ||||

| Ca | Adults | 1000 | 2.2 | 6.7 |

| Fe | Male | 8 | 2.16 | 9.94 |

| Female | 18 | 0.96 | 4.42 | |

aDRIs: Dietary Reference Intake set by the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Research Council for male and female adults (30–50 years of age)

Optimized cookie had similar protein (3.72 ± 0.11 %) and carbohydrate (66.7 ± 0.88 %) content as gluten-containing cookies (2.45–6.0 % and 66.0–72.0 %, respectively). Optimal proportion of pomace added in gluten-free formulation resulted in increase in dietary fiber content from 0.15 ± 0.02 % to 7.80 ± 0.11 %. An average daily portion of optimized cookies (50 g) would meet 10.3 % and 15.6 % of DRIs for dietary fibers for male and female adults, respectively. Since the content of dietary fibers in the group of gluten containing cookies would meet 12 % to 20 % of DRIs (based on dietary fiber daily intake of 25 g) it can be concluded that optimized formulation is comparable with gluten-containing counterparts. This novel value-added product could be considered as a good fiber source (FDA 2013) and may contribute to the enhancement of dietary fibers status of celiac patients.

In general, cookies are food products containing high amount of sugar and fat which provide adequate dough handling and baking properties, structural and textural characteristics of a final product, as well as richness of taste, mouthfeel and flavor intensity. Since gluten-free cereal products are commonly perceived to have dry, sandy mouthfeel and flat aroma (Lazaridou and Biliaderis 2009). the addition of high amount of sugar and fat make them more palatable, but contribute to the high calorie content of the product.

It must be emphasized that cookie formulation optimized within this study evidently contained lower fat content (10.97 ± 0.22 %) in comparison to that of commercially available cookies used for the comparison (16.0–20.7 %), without impairing their structural and textural properties and overall sensory quality. Analysis of fatty acid composition showed that inclusion of raspberry and blueberry pomace in gluten-free cookie formulation has led to a significant increase in content of essential ω-6 and ω-3 fatty acids. Linoleic acid content increased approximately two-fold, while in the case of the α-linolenic acid, the increase was approximately 25-fold. Daily portion of the optimized cookies meets 5.00 % and 7.73 % of DRIs (for male and female) for linoleic acid and 23.6 % and 34.3 % of DRIs for α-linolenic acid. A consumption of α-linolenic acid has been considered as important for prevention of coronary heart disease due to hypolipidemic, antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory effects of this ω-3 fatty acid (Wolfram 2003). Since gluten-free diet is characterized by the predominance of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, formulation of a novel gluten-free products containing higher amount of polyunsaturated fatty acids could be a promising area of research innovation.

Gluten-free products are often low in micronutrients therefore contributing to the risk of deficiencies (Thompson et al. 2005). Recent dietary surveys reported inadequate intake of iron and calcium in more than 50 % of studied female patients. Additionally, deficiency of these important nutrients is caused by maldigestion and malabsorption associated with celiac disease (Niewinski 2008). In the general population, fortified wheat-based cereal products highly contribute to the daily intake of iron. Although fortification is an effective approach to increase dietary iron intake, most of gluten-free products and ingredients are not fortified. Prevalence of iron-deficiency anaemia in celiac patients is 12–60 % and is common in long-standing, untreated disease (Tikkakoski et al. 2007). By substituting gluten-free flour mixture with optimized proportion of raspberry and blueberry pomace, significant increase in iron content was achieved. Optimized cookie formulation meets 9.94 % and 4.42 % of DRIs (for male and female) for iron, which makes this gluten-free cookie similar to gluten-containing counterparts (6–10 % of DRIs). Most of analyzed cookies containing gluten were prepared using fortified flour, which additionally highlight the remarkable nutritive profile of pomace and its potential application as functional ingredient. Calcium deficiency in celiac patients is very common and may occur due to malabsorption or low intake of milk and dairy products (Niewinski 2008). Addition of raspberry and blueberry pomace in optimal proportion resulted in significantly higher content of calcium than in control cookie.

Conclusion

Drying of raspberry and blueberry pomace yield in fruit concentrates, rich in polyphenolic compounds, essential fatty acids, dietary fibers and minerals, which can successfully be used as functional ingredients to improve the nutritional quality of gluten-free products. Application of response surface methodology approach, relying on best sensory properties and best nutritional quality criteria, proved to be an efficient strategy in the development of novel gluten-free cookie formulations.

Apart from increase in the content of phenolic compounds, dietary fibers and minerals, reduction in fat content and improvement of fatty acid composition was achieved in comparison to available gluten-free cookies in the market. That fact is of a particular importance, since gluten-free bakery products tend to be high in fat and calories, in order to ensure sensory and textural properties acceptable to consumers. Optimized cookie represents a novel value-added product which may be offered to the celiac patients as a valuable source of important nutrients.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development, Republic of Serbia (Project No: TR-31029).

Footnotes

1. Berry juice by-products were processed and utilized as food ingredients.

2. Novel gluten-free cookie with blueberry and raspberry pomace was formulated.

3. Cookie is high in fiber, phenolics, Fe, Ca, with good fatty acid profile, low in fat.

4. Improved contribution to dietary reference intakes was achieved.

References

- Ajila CM, Leelavathi K, Prasada Rao UJS. Improvement of dietary fiber content and antioxidant properties in soft dough biscuits with the incorporation of mango peel powder. J Cereal Sci. 2008;48:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2007.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alao AR, Konneh M. A response surface methodology based approach to machining processes: modelling and quality of the models. Ijedpo. 2009;1:241–260. doi: 10.1504/IJEDPO.2009.030320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis. 17th. Washington DC: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bardella MT, Fredella C, Prampolini L, Molteni N, Giunta AM, Bianchi PA. Body composition and dietary intakes in adult celiac disease patients consuming a strict gluten-free diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:937–939. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.4.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobinaitė R, Viškelis P, Šarkinas A, Venskutonis PR. Phytochemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of raspberry fruit, pulp, and marc extracts. CyTA – Journal of Food. 2013;11(4):334–342. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2013.766265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Četojević-Simin D, Velićanski A, Cvetković D, Markov S, Ćetković G, Tumbas Šaponjac V, Vulić J, Čanadanocić-Brunet J, Đilas S. Bioactivity of Meeker and Willamette raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) pomace. Food Chem. 2015;166:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Sun Y, Zhao G, Liao X, Hu X, Wu J, Wang Z. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of anthocyanins in red raspberries and identification of anthocyanins in extract using high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Ultrason Sonochem. 2007;14:767–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csengeri I, Čolović D, Rónyai A, Jovanović R, Péter-Szűcsné J, Sándor Z, Gyimes E. Feeding of common carp on floating feeds for enrichment of fish flesh with essential fatty acids. Food and Feed Research. 2013;40:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- De Brito ES, De Araújo MC, Alves RE, Carkeet C, Clevidence BA, Novotny JA. Anthocyanins present in selected tropical fruits: acerola, jambolão, jussara, and guajiru. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:9389–9394. doi: 10.1021/jf0715020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elleuch M, Bedigian D, Roiseux O, Besbes S, Blecker C, Attia H. Dietary fibre and fibre-rich by-products of food processing: characterisation, technological functionality and commercial applications: a review. Food Chem. 2011;124:411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.06.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FDA (2013) Guidance for Industry: A Food Labeling Guide (10. Appendix B: Additional Requirements for Nutrient Content Claims). Available from http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm064916.htm

- Flores FP, Singh RK, Kong F. Physical and storage properties of spray-dried blueberry pomace extract with whey protein isolate as wall material. J Food Eng. 2014;137:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.03.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giusti MM, Wrolstad RE. Current protocols in food analytical chemistry, wrolstad RE (ed) New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. Anthocyanins. Characterization and measurement with UV visible spectroscopy; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves B, Silva AP, Moutinho-Pereira H, Bacelar E, Rosa E, Meyer AS. Effect of ripeness and postharvest storage on the evolution of colour and anthocyanins in cherries (Prunus avium L.) Food Chem. 2006;103:976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Górecka D, Pachołek B, Dziedzic K, Górecka M. Raspberry pomace as a potential fibersource for cookies enrichment. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment. 2010;9(4):451–462. [Google Scholar]

- Gujral N, Freeman JH, Thomson A. Celiac disease: prevalence, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6036–6059. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallert C, Grant C, Grehn S, Grännö C, Hultén S, Midhagen G, Svensson H, Valdimarsson T. Evidence of poor vitamin status in coeliac patients on a gluten-free diet for 10 years. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1333–1339. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopman GDE, Le Cessie S, Von Blomberg EBM, Mearin LM. Nutritional management of the gluten-free diet in young people with celiac disease in The Netherlands. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:102–108. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000228102.89454.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islas-Rubio AR, De la Barca AC, Cabrera-Chávez F, Cota-Gastélum A G, Beta T. Effect of semolina replacement with a raw: popped amaranth flour blend on cooking quality and texture of pasta. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2014;57:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joglekar AM, May AT. Product excellence through design of experiments. Cereal Foods World. 1987;32:857–868. [Google Scholar]

- Khanal RC, Howard LR, Brownmiller CR, Prior RL. Influence of extrusion processing on procyanidin composition and total anthocyanin contents of blueberry pomace. J Food Sci. 2009;74:H52–H58. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korus J, Juszczak L, Ziobro R, Witczak M, Grzelak K, Sójka M. Defatted strawberry and blackcurrant seeds as functional ingredients of gluten-free bread. J Texture Stud. 2011;43:29–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.2011.00314.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larrauri JA, Rupérez P, Saura-Calixto F. Effect of drying temperature on the stability of polyphenols and antioxidant activity of red grape pomace peels. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45:1390–1393. doi: 10.1021/jf960282f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridou A, Biliaderis CG. Gluten-free doughs: rheological properties, testing procedures – methods and potential problems. In: Gallagher E., editor. Gluten-free food science and technology. Chichester, UK: Blackwell Pub. Professional; 2009. pp. 52–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Wrolstad RE. Extraction of anthocyanins and polyphenolics from blueberry processing waste. J Food Sci. 2004;69:C564–C573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2004.tb13651.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MAFF (Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food) Fatty acids. In: McCance and Widdowson’s –The composition of foods, The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, London, UK, seventh supplement; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Niewinski M. Advances in celiac disease and gluten-free diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:661–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nile SH, Park SW. Edible berries: bioactive components and their effect on human health. Nutrition. 2014;30:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC (National Research Council) Recommended dietary allowances. 10th. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea N, Rößle C, Arendt E, Gallagher E. Modelling the effects of orange pomace using response surface design for gluten-free bread baking. Food Chem. 2015;166:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.05.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa M R, Kesseler AG, Vullioud MB, Lozano JE. Physical and chemical characteristics of raspberry pulp: storage effect on composition and color. LWT Food Sci Technol. 1999;32:149–153. doi: 10.1006/fstl.1998.0518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parry J, Yu L. Fatty acid content and antioxidant properties of cold-pressed black raspberry seed oil and meal. J Food Sci. 2004;69:FCT189–FCT193. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlović A, Kevrešan Ž, Kelemen-Mašić Đ, Mandić A (2001) Micro and toxic elements in skin, meat and gills of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). In: Proc of the 8th Symposium on Analytical and Environmental Problems, Szeged, Hungary, October 1

- Pestorić M, Mišan A, Šimurina O, Jambrec D, Belović M, Gubić J, Nedeljković N. Sensory and instrumental properties of cookies enriched with “vitalplant” extract. Agro Food Ind Hi Tech. 2014;25:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Popov-Raljić J, Mastilović J, Laličić-Petronijević J, Kevrešan Ž, Demin M. Sensory and color properties of dietary cookies with different fiber sources during 180 days of storage. Hem Ind. 2013;67:123–134. doi: 10.2298/HEMIND120327047P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prior RL, Cao G, Martin A, Sofic E, McEwen J, O’Brien C, Lischner N, Ehlenfeldt M, Kalt W, Krewer G, Mainland CM. Anthocyanin content, maturity, and variety of vaccinium species. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:2686–2693. doi: 10.1021/jf980145d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Routray W, Orsat V. Blueberries and their anthocyanins: factors affecting biosynthesis and properties. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2011;10:303–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00164.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rupasinghe V, Wang L, Huber GM, Pitts N. Effect of baking on dietary fibre and phenolics of muffins incorporated with apple skin powder. Food Chem. 2008;107:1217–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Sakač M, Torbica A, Sedej I, Hadnađev M. Influence of breadmaking on antioxidant capacity of gluten free breads based on rice and buckwheat flours. Food Res Int. 2010;44:2806–2813. [Google Scholar]

- Sedej I, Sakač M, Mandić A, Mišan A, Pestorić M, Šimurina O, Čanadanović-Brunet J. Quality assessment of gluten-free crackers based on buckwheat flour. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2011;44:694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2010.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventos RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:152–178. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souza VR, Pereira PA, Silva TLT, Lima LC, Pio R, Queiroz F. Determination of the bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity and chemical composition of Brazilian blackberry, red raspberry, strawberry, blueberry and sweet cherry fruits. Food Chem. 2014;156:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T, Dennis M, Higgins LA, Lee AR, Sharrett MK. Gluten-free diet survey: are Americans with coeliac disease consuming recommended amounts of fibre, iron, calcium and grain foods? J Hum Nutr Diet. 2005;18:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2005.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkakoski S, Savilahti E, Kolho KL. Undiagnosed coeliac disease and nutritional deficiencies in adults screened in primary health care. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:60–65. doi: 10.1080/00365520600789974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram G. Dietary fat in prevention of coronary fat disease. Forum Nutr. 2003;56:65–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]