Abstract

Background:

This study aimed to highlight the proportion of disordered eating attitudes among university students in Kuwait by gender and obesity.

Methods:

A sample of 530 Kuwaiti university students was selected from four universities in Kuwait (203 men and 327 women). The eating attitudes test-26 was used to determine disordered eating attitudes.

Results:

The prevalence of disordered eating attitudes was 31.8% and 33.6% among men and women respectively. Obese students of both genders had doubled the risk of disordered eating attitudes compared to nonobese students (odds ratio 1.99 and 1.98, respectively).

Conclusions:

About one third of university students in Kuwait had disordered eating attitudes. There is an urgent need to prevent and treat disordered eating attitudes in university students in Kuwait.

Keywords: Arab, eating disorders, obesity, university students

INTRODUCTION

The impact of nutrition transition on eating behavior in the Arab Gulf states, including Kuwait, has been well recognized.[1] It has been found that such transition, along with high socioeconomic status, has led to a high prevalence of obesity and its related chronic noncommunicable diseases in these countries.[2] In Kuwait, the proportions of overweight and obesity are considered among the highest in the world. Using body mass index (BMI), it was indicated that 78% of men and 82% of women in Kuwait were overweight and obese.[3] Furthermore, the influence of Western culture on the dietary habits and lifestyle of Kuwaiti people has been very substantial, especially that related to body weight concern. Western values such as thinness as a sign of perfect body shape are widely spread in Kuwait, particularly among women.[4] Obesity and body weight concern have been reported to be risk factors for unhealthy food behavior leading to eating disorders.[5] The prevalence of eating disorders has increased dramatically during the recent decades in both developing and developed countries, especially among young people. It was reported that the proportion of eating disorders among children and adolescents in Western countries is higher than that of type 1 diabetes.[6]

According to the American Psychological Association[7] eating disorders can be defined as abnormal eating habits that can threaten people's health or even people's life. They include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating. Many people worry about their weight occasionally, however people with eating disorders take such concerns to extremes. Eating disorders have serious health consequences that affect a person's emotional, productivity, relationship, and physical health.[8] However, despite these facts, eating disorders have not been given an attention in the health services in developing countries, including Kuwait. Regardless their high prevalence, and associated morbidity and mortality, eating disorders continue to be under-diagnosed by health professionals.[6]

Studies on eating disorders in Arab countries are mostly focused on female adolescents[9,10,11] or female college students,[12,13] and none are focused on male university students. It was found that university students are at risk of subclinical and clinical disordered eating and body dissatisfaction.[14] This study is the first attempt to investigate eating disorders among university women and men in Kuwait. The only cross-cultural study that included Kuwait demonstrated a very high prevalence of disordered eating attitudes: 47% of male and 42.8% of female Kuwaiti adolescents aged 15–18 years had these attitudes, using eating attitudes test (EAT-26).[15] Therefore, it is expected that the disordered eating attitudes will also to be high among university students. Thus, the aim of this short study was to answer two questions: How high is the prevalence of disordered eating attitudes among university males and females in Kuwait? And what is the role of obesity in this prevalence?

METHODS

Study design and participants

A total sample of 530 students was selected at convenience from two public and two private universities in Kuwait (203 men and 327 women). The age of students ranged between 19 and 26 years. The mean age of men was 21.5 ± 3.5 year, compared to 20.6 ± 2.6 year for women (P < 0.001). The mean BMI for men and women was 26.5 ± 7.5 and 22.9 ± 4.9, respectively (P < 0.001). The sample was selected proportionally to the total number of students in each college. The university students were interviewed by Kuwaiti medical students during breaks between classes or at lunch break. All the participants were informed about the objective of the study before answering the questionnaire. The study was approved ethically by the Family and Community Medicine Department at the College of Medicine and Medical Sciences in the Arabian Gulf University in Bahrain. The date of approval was 15 January. 2010. Data were collected in 2010.

Study instruments and variable assessment

The risk of disordered eating attitudes was measured using the EAT-26 developed by Garner et al.[16] This test has been validated and used in several developing and developed countries. The Arabic version of this test was first validated by Al-Subaie et al.[17] Its sensitivity and specificity were 100% and 84.6%, respectively. The test was applied in many Arab countries.[9,10,11] The test consists of 26 statements related to various aspects of eating attitudes, and the answer to each is chosen from the following options: Always, usually, often, sometimes, rarely, or never. A special score is given to each answer. Based on the statistical calculation, it was found that participant was considered at risk of disorders eating attitudes and needed to be evaluated further by mental health professional when the total score was 20 or above.

Weight and height were obtained by self-reporting, and students who did not know their weight and/or height were excluded from the study. Obesity was calculated based on BMI according to World Health Organization classification.[18]

Statistical analysis

For the purpose of analysis, the students were grouped into two categories: Nonobese (BMI <25) and overweight and obese (BMI ≥25). Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical package version 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to measure the risk of positive eating attitudes by gender and obesity, using logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS

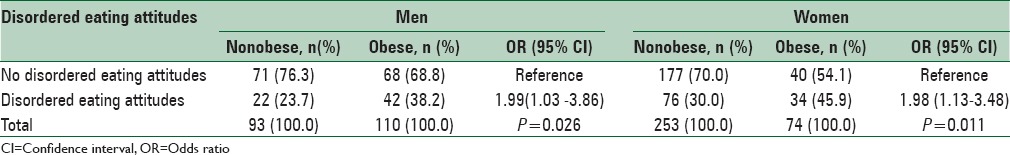

The total prevalence of disordered eating attitudes was 31.8% and 33.6% among men and women, respectively. Table 1 shows the association of gender and obesity with the risk of disordered eating attitudes. The risk of disordered eating attitudes among obese men and women was significantly twice that found among their nonobese counterparts (odds ratios 1.99 [95% CI: 1.03–3.86], P < 0.026, and 1.98 [95% CI: 1.13–3.48], P < 0.011).

Table 1.

Prevalence and risk of disordered eating attitudes among Kuwaiti university students by gender and obesity

DISCUSSION

Disordered eating attitudes include a wide range of symptoms, such as dieting, eating attitudes, weight concern, binge eating, anorexia, and bulimia. This study confirms the existence of disordered eating attitudes among university students in Kuwait. However, the prevalence of disordered eating attitudes among these students was lower than that among Kuwaiti adolescents. It was reported that 47% of Kuwaiti adolescent males and 42.8% of Kuwaiti adolescent females had disordered eating attitudes,[15] compared to 31.8% of male university students and 33.6% of female university students found in this study. This is may be due to the fact that during adolescence, both boys and girls become more sensitive than older people, to weight and body shape criticisms and teasing by parents and peers. This may leads to body dissatisfaction, which in turns lead to unhealthy eating behavior. Another explanation is the sample of this study is cross-sectional and different than that of adolescents. Nevertheless, such conclusions need further investigation. However, the proportion of disordered eating attitudes in Kuwaiti university students was higher than in their counterparts in Arab Gulf (24% in females),[13] Asian (9.9% in females and 2% in males),[19] and Western (12% in both genders)[20] countries.

Obesity was found to be linked with eating disorders in our Kuwaiti sample. Obesity has been reported to be associated with eating disorders.[21,22] This is mainly due to the similarity of the risk factors for both symptoms, such as body weight concern, being eating, low self-esteem, dieting, media exposure, body image dissatisfaction, weight-related teasing, and shared susceptibility genes.[23] Moreover, it has been observed that disordered eating attitudes, particularly bulimic behaviors; predict sleep disturbances overtime[24] and that short sleep duration, which occurs more frequently in modern societies, has been associated with increased obesity.[25] Our finding concerning the link of obesity with eating disorders is consistent with the results reported by Herbozo et al.[26] in the USA, as obese college women are more likely to have negative weight concern than nonobese women. Musaiger and Al-Mannai[4] showed that 30% of nonobese and 81% of obese Kuwaiti college women were dissatisfied with their current weight.

Several factors may be associated with the high prevalence of disordered eating attitudes among Kuwaiti university students, such as rapid change in lifestyle and food habits, the influence of Westernized mass media, socio-cultural norms, and high economic status. The country of Kuwait experienced the nutrition and cultural transitions earlier than most Arab countries, which resulted in a great change in attitudes and behaviors of the people to more western values such as thinness as an ideal body shape. Such attitude is widely promoted in the media, especially in western media. It was found that females exposed to Westernization in developing countries reported to be more concerned about their weight and dieting than those who were not exposed.[27] People with a high socioeconomic status (such in the case of Kuwaiti people) were more likely to have disordered eating attitudes than those at a low socioeconomic level.[5] It was found that Westernized mass media such as magazines, television, and the internet had a significant influence on dieting to lose weight and the idea of a perfect body shape among female university students in Kuwait.[4]

One limitation should be considered when interpreting the results of this survey. The weight and height of the college students depended on self-reporting. However, we assumed that due to high awareness of weight concern, the students knew their exact weight and height.

CONCLUSIONS

This study is the first to obtain data on the prevalence of disordered eating attitudes in Kuwaiti university students. The inclusion of male university students adds more positive value to this study, as all previous studies in Arab countries have focused on females. The results support the generally held assumption that these attitudes are widely prevalent in Kuwait. This highlights the need for further assessment of eating disorders and their association with obesity, and the provision of prevention of university students in Kuwait.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ng SW, Zaghloul S, Ali HI, Harrison G, Popkin BM. The prevalence and trends of overweight, obesity and nutrition-related non-communicable diseases in the Arabian Gulf States. Obes Rev. 2011;12:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musaiger AO, Al-Hazzaa HM. Prevalence and risk factors associated with nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:199–217. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S29663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musaiger AO. Overweight and obesity in Eastern Mediterranean region: Prevalence and possible causes. J Obes 2011. 2011;2011:407237. doi: 10.1155/2011/407237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musaiger AO, Al-Mannai M. Role of obesity and media in body weight concern among female university students in Kuwait. Eat Behav. 2013;14:229–32. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers L, Resnick MD, Mitchell JE, Blum RW. The relationship between socioeconomic status and eating-disordered behaviors in a community sample of adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;1:15–23. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199707)22:1<15::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell K, Peebles R. Eating disorders in children and adolescents: State of the art review. Pediatrics. 2014;134:582–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychological Association. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 08]. Available from: http://www.apa.org/topics/eating/index.aspx .

- 8.National Eating Disorders Association. Health Consequences of Eating Disorders. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 08]. Available from: http://www.ndsu.edu/fileadmin/counseling/Health_Consequences.pdf .

- 9.Al-Subaie AS. Some correlations of dietary behavior in Saudi school girls. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;4:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eapen V, Mabrouk AA, Bin-Othman S. Disordered eating attitudes and symptomatology among adolescent girls in the United Arab Emirates. Eat Behav. 2006;7:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mousa TY, Al-Domi HA, Mashal RH, Jibril MA. Eating disturbances among adolescent school girls in Jordan. Appetite. 2010;54:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Afifi-Soweid RA, Kteily MB, Schediac-Rizkallah MC. Preoccupation with weight and disordered behaviors of entering students at a university in Lebanon. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;32:52–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.10037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas J, Khan S, Abdulrahman AA. Eating attitudes and body image concerns among female university students in the United Arab Emirates. Appetite. 2010;54:595–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yager Z, O’Dea JA. Prevention programs for body image and eating disorders on university campuses: A review of large, controlled interventions. Health Promot Int. 2008;23:173–89. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dan004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musaiger AO, Al-Mannai M, Tayyem R, Al-Lalla O, Ali EY, Kalam F, et al. Risk of disordered eating attitudes among adolescents in seven Arab countries by gender and obesity: A cross-cultural study. Appetite. 2013;60:162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med. 1982;12:871–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Subaie A, Al-Shammari S, Bamgboye E, Al-Sabhan K, Al-Shehri S, Bannah AR. Validity of the Arabic version of the eating attitude test. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;20:321–4. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199611)20:3<321::AID-EAT12>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1998. World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and Managing the Global Epidemic. WHO Technical Report Series 894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tao ZL. Epidemiological risk factor study concerning abnormal attitudes toward eating and adverse dieting behaviours among 12- to 25-years-old Chinese students. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2010;18:507–14. doi: 10.1002/erv.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sira N, Pawlak R. Prevalence of overweight and obesity, and dieting attitudes among Caucasian and African American college students in Eastern North Carolina: A cross-sectional survey. Nutr Res Pract. 2010;4:36–42. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2010.4.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Guo J, Story M, Haines J, Eisenberg M. Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: How do dieters fare 5 years later? J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:559–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill AJ. Obesity and eating disorders. Obes Rev. 2007;8(Suppl 1):151–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Day J, Ternouth A, Collier DA. Eating disorders and obesity: Two sides of the same coin? Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bos SC, Soares MJ, Marques M, Maia B, Pereira AT, Nogueira V, et al. Disordered eating behaviors and sleep disturbances. Eat Behav. 2013;14:192–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjorvatn B, Sagen IM, Øyane N, Waage S, Fetveit A, Pallesen S, et al. The association between sleep duration, body mass index and metabolic measures in the Hordaland Health Study. J Sleep Res. 2007;16:66–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herbozo S, Menzel JE, Thompson JK. Differences in appearance-related commentary, body dissatisfaction, and eating disturbance among college women of varying weight groups. Eat Behav. 2013;14:204–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viernes N, Zaidan ZA, Dorvlo AS, Kayano M, Yoishiuchi K, Kumano H, et al. Tendency toward deliberate food restriction, fear of fatness and somatic attribution in cross-cultural samples. Eat Behav. 2007;8:407–17. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]