Abstract

Background:

Recently, tissue engineering has developed approaches for repair and restoration of damaged skeletal system based on different scaffolds and cells. This study evaluated the ability of differentiated osteoblasts from adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) seeded into hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate (HA-TCP) to repair bone.

Methods:

In this study, ADSCs of 6 canines were seeded in HA-TCP and differentiated into osteoblasts in osteogenic medium in vitro and bone markers evaluated by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was applied for detection of cells in the pores of scaffold. HA-TCP with differentiated cells as the test group and without cells as the cell-free group were implanted in separate defected sites of canine's tibia. After 8 weeks, specimens were evaluated by histological, immunohistochemical methods, and densitometry test. The data were analyzed using the SPSS 18 version software.

Results:

The expression of Type I collagen and osteocalcin genes in differentiated cells were indicated by RT-PCR. SEM results revealed the adhesion of cells in scaffold pores. Formation of trabecular bone confirmed by histological sections that revealed the thickness of bone trabecular was more in the test group. Production of osteopontin in extracellular matrix was indicated in both groups. Densitometry method indicated that strength in the test group was similar to cell-free group and natural bone (P > 0.05).

Conclusions:

This research suggests that ADSCs-derived osteoblasts in HA-TCP could be used for bone tissue engineering and repairing.

Keywords: Adipose-derived stem cells, animal model, bone repair, hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate

INTRODUCTION

Since large bone lesions never heal spontaneously, the repair and regeneration of bone defects is a major clinical challenge.[1,2] Currently, autograft, allograft, xenograft, and Allizarov methods have been used for the bone repair.[3,4] These methods have disadvantages such as the antigens transfer, the need for invasive surgery, donor site morbidity, limited available bone, and absorption of the bone graft.[4] Furthermore, the use of mechanical devices or artificial organs have limitations because of the risk of infection, obstruction of the blood flow, and the low durability.[5] Thus, tissue engineering based on different scaffolds and cells has been developed for the repair and restoration of damaged skeletal system.[6,7]

Bio ceramics, polyesters, and hydrogels are used as drugs or growth factor deliveries and as scaffolds in bone tissue engineering.[7,8,9,10]

Although polyesters have better mechanical properties, they produce acidic materials and cause inflammation.[11,12] In contrast, bioceramics such as hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate (HA-TCP) display excellent osteoconductive properties and could be designed in the appropriate shape and size without any inflammation and rejection following transplantation.[13,14,15,16] Moreover, implanted bioceramics in contact with bone matrix and cells induces repair of damaged and degenerated tissues.[17] The choice of suitable cell source cell is vital for the engineering of bone tissue. The ethical issues and the poor known characteristics limit the use of embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells.[18]

Adipose tissue is an attractive source for stem cells.[19] Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) are multi potent which can differentiate into variety of cell lineages.[20] ADSCs have various advantages over the bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) such as the ease of accessibility, the abundance in number, high proliferation rate, and no need to preserve for long time in cell banks.[21,22,23]

Studies have demonstrated that ADSCs could be differentiated into bone cells and produce organic and mineralized extracellular matrix and alkaline phosphatase enzyme in vitro.[24] Auto and allograft transplant of ADSCs is possible without the risk of rejection or transfer of contagious diseases due to their lack of HLA-DR antigens.[23] Some researchers have reported the benefits of ADSCs-scaffold constructs, such as collagen and alginate scaffold, in regenerative medicine.[25,26]

In this study, the repair of tibial defects in animal model was investigated with differentiated osteoblasts from ADSCs in HA-TCP scaffold in comparison to the cell-free HA-TCP.

METHODS

Adipose tissue harvesting

In this experiment, six healthy dogs with average weight of 20–35 kg were used. Ethical principles in animal researches were considered. Ketamine (15 mg/kg) (Alfasan, Holland) and xylazine 2 mg/kg intramuscular with orotracheal intubation were used for anesthesia followed by respiratory administration of halothane and N2O. After injecting local anesthesia with lidocaine 2% plus epinephrine 1:100,000, an incision with a length of 5 cm was performed in cervical area. After dissection, about 20 g subcutaneous fats were harvested and maintained in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma).

Isolation of adipose-derived stem cells

Canine ADSCs were isolated according to previous protocol.[18] Fat tissue was washed with PBS (Sigma) and digested with Type I collagenase enzyme (1 mg per 1 g tissue) at 37°C for 30 min. After centrifuge, cell pellet resuspended and cultured in Dulbecco modified eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco®) supplemented with fetal bovine serum 10% (Gibco®) and penicillin-streptomycin 1% (Gibco®). Nonadherent cells were removed from culture by medium changing. Hence, adherent cells were expanded as monolayer cultures at 5% CO2 with a temperature of 37°C. Medium was changed twice every week.

Osteogenic induction

After expansion in the control medium, 5 × 106 cells/ml ADSCs were seeded onto witted HA-TCP blocks scaffold which were purchased from Ceraform Co., Germany, in the size of 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm (35–65%) and cultured in osteogenic medium. The osteogenic medium contained DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM b-glycerol-3-phosphate (Sigma), 10 nM dexamethasone (Sigma), 100 mg/ml L-ascorbic acid (Sigma), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The medium was replaced every 3 days and after 14 days, scaffold/cell investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Scanning electron microscopy

The blocks of HA-TCP/cell were washed with PBS and fixed with glutaraldehyde 2.5% for 2 h. Then, blocks were dehydrated by ascending ethanol and coated by thin layer of gold by sputter coater. Prepared samples were visualized by SEM (Philips XL 30).

In vivo implantation and specimen harvesting

The canines were anesthetized and after sterilization of skin, tibia bone was exposed and two cylindrical defected sites in 10 mm diameter were created on the anterior aspect of tibia by trephine bur (Meisinger, Dusseldorf, Germany) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

(a) Cylindrical defects on the anterior aspect of tibia by trephine bur. (b) After 8 weeks, biopsies from repaired sites were removed for histological evaluation

The defected sites were filled with HA-TCP contained differentiated cells as the test group and without cells as the cell-free group and marked with titanium screw. The wound was closed in layered fashion (Vicryl 3.0, GmbH and Co., KG - Norderstedt, Germany). After the surgery, animals received ceftriaxone 1 g intravenous (Loghman pharmaceutical and Hygienic Co.) daily for 5 days.

After 8 weeks similar to previous surgery, animals were anesthetized and prepared for surgery. Biopsies were applied by a larger trephine bur (12.0 mm) and used for histological, immunohistochemical (IHC) methods, and densitometry test.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis

The expression of specific bone markers (Type I collagen and osteocalcin) was proved with RT-PCR. Cells RNAs isolated by RNX-plus Isolation Kit (CinnaGen Inc., Iran); cDNA was synthesized from extracted RNA using First-strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Frementase). For PCR reaction, cDNA, dNTPs, PCR buffer, Taq DNA polymerase, and primers (Frementase) were used.

PCR reaction mixture contained 2.5 μl cDNA, 1 × PCR buffer (AMS), 200 μM dNTPs, 1 unit Taq DNA Polymerase (Fermentas), and 0.5 μM of each primer (osteocalcin: forward 5’-ACACTCCTCGCCCTATTG -3’; reverse 5’- GATGTGGTCAGCCAACTC- 3’, 371 bp, Type I collagen: forward, 5’- ACTTAGAGTATCTATAAACTTGATACTC- 3’, reverse, 5’- TAAATTGTTACTAAGCATATTATAATTAACATC -3’599 bp).

For amplification, initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 93°C, 65°C, and 72°C for 30, 45, and 40 s, respectively. The PCR results were determined in 1% agarose gel and then stained by ethidium bromide staining and visualized by UV trans-illuminator. After fixation of samples in neutral buffered formalin 10% and decalcification by using of EDTA solution, samples were dehydrated with ethyl alcohol, cleared with xylene, and embedded with paraffin. These blocks were sectioned with microtome at 5 μm thickness. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. In addition, trichrome mallory staining was done as described.[3] In this procedure, the sections stained in acid fuschin 1% (Merck) solution and then aniline blue 0.5% (Merck), orange G 2% (Merck), and oxalic acid 2% (Sigma) in distilled water.[3]

Immunohistochemistry

For antigen retrieval, the specimens were deparaffinized and treated with citrate buffer 0.01 mol/l, pH 6.0 (Merck), heated at 100°C for 6 × 2 min.

For blocking of endogenous peroxidase, sections were incubated in H2O2 3% for 10 min. The mouse monoclonal antibody against osteopontin (1:300 concentration; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) was used at 4°C overnight. Then, specimens were incubated in secondary antibody conjugated with horse radish peroxidase (Abcam) for 30 min. After staining with diaminobenzidine (Sigma), hematoxylin dye was used to counter staining.

Densitometry test

Some of the biopsy samples were placed in acrylamide mold for analyzing their average strength and evaluated by “Tensometer Universal” equipment. Then, the rates of strength were compared with normal tissues and the control group.

Statistical analysis

All data were considered as means and standard deviation. The data were subjected to statistical analysis using the Wilcoxon test. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered significant in this study.

RESULTS

Cell culture

The canine ADSCs in third passage were observed with spindle fibroblast-like cells within a homogeneous monolayer culture [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Subcutaneous adipose-derived stem cells in third passage (×40)

For induction of osteogenic differentiation, ADSCs of third passage were seeded in HA-TCP scaffold and were cultured in osteogenic medium. SEM results represented that the stem cells have adhered in the pores of the scaffold and their processes extended and connected together [Figure 3a].

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopy technique: (a) Stem cells adhered in the pores of scaffold (b) extracellular matrix as deposition of granular products secreted by differentiated osteoblasts in the pores of hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate scaffold

Osteoblasts secreted extracellular matrix as deposition of granules after osteogenesis induction [Figure 3b].

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction result

RT-PCR results indicated the expression of Type I collagen and osteocalcin genes in differentiated osteoblasts derived from ADSCs. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as a housekeeping gene has been expressed in all cells [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Expression of Type I collagen and osteocalcin genes in differentiated osteoblasts derived from adipose-derived stem cells. Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase as a housekeeping gene had expressed in all groups

Histological results

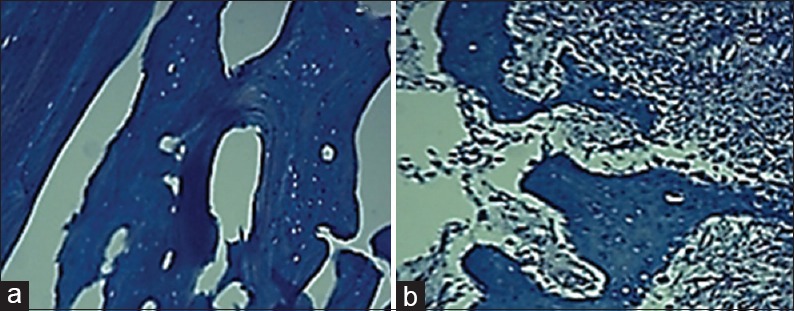

Evaluation of tissue sections revealed the formation of bone trabeculae and lacunae. This histological evaluation showed that the bone trabecular and the mineral matrices were thicker in the test group rather than the cell-free group [Figures 5 and 6].

Figure 5.

Formation of bone tissue with trabeculae in bone defects. (a) Cell-free group, (b) test group (H and E, ×100)

Figure 6.

Trichrome mallory staining indicated the existence of Type I collagen in bone matrix in both groups. (a) Cell-free group (b) test group (×100)

Analysis of IHC results showed the existence of osteopontin glycoprotein in the matrix of two groups, which is considered as an important bone marker [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Analysis of intracerebral hemorrhage for production of osteopontin

Densitometry result

Densitometry method indicated that the strength in the test group was approximately similar to the cell-free group and natural bone (P > 0.05) [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

The rates of strength were evaluated between hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate with osteoblast, hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate without cells and natural bone tissue via densitometry

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the ability of the differentiated osteoblasts, obtained from ADSCs and seeded into HA-TCP, to repair the bone defects in comparison to HA-TCP alone and natural bone.

Our results indicated that the thickness of the bone trabecular was more in the test group compared to the cell-free group. The production of osteopontin in the extracellular matrix was observed in both groups. The bone strength in the test group was similar to the cell-free group and natural bone as shown by the densitometry.

Stem cell-derived osteoblasts play an important role in the bone tissue engineering which were considered by researchers.[7,27,28] The final aim of tissue engineering is to regenerate new tissues via mediators, scaffolds, and biological matrices. Different natural and synthetic scaffolds were used for tissue engineering in the bone repair.[25,26,29,30,31] However, scaffolds with similarities to the bone matrix could provide a suitable microenvironment for MSCs adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation in osteogenesis.[32,33,34]

Hydroxyapatite is an important element of the bones; regarding chemical structure and physical properties, it is similar to the natural bone and it is appropriate for bone tissue engineering.[35,36]

Hydroxyapatite composed by tricalcium phosphate (HA-TC) has been used with different HA to TCP ratios, but bone formation was detected only in HT73 (HA to TCP ratio, 7-3) specimens.[35]

Rathbone et al. reported that HA increased the density of the bone mineral of defected radius compared to controls in a rabbit model.[37] Another study compared cellseeded HA scaffolds by bone marrow stem cell and HA scaffolds without cell in the bone regeneration after 8 weeks, they showed no difference in bone formation between two groups.

Our study showed that the thickness of the bone trabecular was more in bone defects implanted by HA-TCP with differentiated osteoblasts (from ADSC) compared to the cell-free scaffolds. The presence of cells in HA-TCP scaffold increased the production of the mineral matrix. The strength of the HA-TCP scaffold with differentiated osteoblasts was significantly more than the cell-free HA-TCP

Kim et al. indicated that autologous osteoblasts produce more mineral matrix than the autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs in a rabbit radial defect model.[38] In our study, differentiated osteoblasts from ADSC produced mineral matrix similar to natural bone, thus differentiation of stem cells to osteoblasts in vitro could compensate the limitation of mineral matrix production by undifferentiated stem cells, as shown in Kim's study. Thus, the status of used stem cells can affect the results differently.

In addition, Pourebrahim et al. compared an autograft corticocancellous tibial to HA-TCP differentiated osteoblasts from ADSCs, in the defects of maxillary bone, they observed that the bone formation is higher in autograft group.[39] However, we compared HA/TCP-differentiated osteoblasts from ADSCs to cell-free HA/TCP in tibia defect and natural bone and showed that formation of bone trabeculae in HA/TCP-differentiated osteoblasts group was more than the cell-free group but less than natural bone while the strength was similar in all groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results indicated that HA-TCP scaffold provides a suitable environment for the differentiation and activity of osteoblasts. Furthermore, differentiated osteoblasts from ADSCs seeded into HA-TCP could be regarded as appropriate factors for bone tissue engineering.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. This manuscript is resulted from project with number: 389334. Hence, has a specific ethic committee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cancedda R, Dozin B, Giannoni P, Quarto R. Tissue engineering and cell therapy of cartilage and bone. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green SA, Jackson JM, Wall DM, Marinow H, Ishkanian J. Management of segmental defects by the Ilizarov intercalary bone transport method. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;280:136–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaRossa D, Buchman S, Rothkopf DM, Mayro R, Randall P. A comparison of iliac and cranial bone in secondary grafting of alveolar clefts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:789–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schantz JT, Hutmacher DW, Lam CX, Brinkmann M, Wong KM, Lim TC, et al. Repair of calvarial defects with customised tissue-engineered bone grafts II. Evaluation of cellular efficiency and efficacy in vivo. Tissue Eng. 2003;9(Suppl 1):S127–39. doi: 10.1089/10763270360697030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alsberg E, Anderson KW, Albeiruti A, Franceschi RT, Mooney DJ. Cell-interactive alginate hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. J Dent Res. 2001;80:2025–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800111501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai X, Lin Y, Ou G, Luo E, Man Y, Yuan Q, et al. Ectopic osteogenesis and chondrogenesis of bone marrow stromal stem cells in alginate system. Cell Biol Int. 2007;31:776–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens MM, Marini RP, Schaefer D, Aronson J, Langer R, Shastri VP. In vivo engineering of organs: The bone bioreactor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11450–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504705102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freihofer HP, Borstlap WA, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM, Voorsmit RA, van Damme PA, Heidbüchel KL, et al. Timing and transplant materials for closure of alveolar clefts. A clinical comparison of 296 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1993;21:143–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes CW, Revington PJ. The proximal tibia donor site in cleft alveolar bone grafting: Experience of 75 consecutive cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2002;30:12–6. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2001.0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordana VN, Frenshney R. Culture of Cell for Tissue Engineering. Wiley, Inc. 2006:412–22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs JR, Nasseri BA, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering: A 21st century solution to surgical reconstruction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:577–91. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02820-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutmacher DW. Scaffolds in tissue engineering bone and cartilage. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2529–43. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito N, Okada T, Horiuchi H, Murakami N, Takahashi J, Nawata M, et al. A biodegradable polymer as a cytokine delivery system for inducing bone formation. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:332–5. doi: 10.1038/86715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen G, Ushida T, Tateishi T. Poly (DL-lactic-co-glycolic acid) sponge hybridized with collagen microsponges and deposited apatite particulates. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;57:8–14. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200110)57:1<8::aid-jbm1135>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George J, Onodera J, Miyata T. Biodegradable honeycomb collagen scaffold for dermal tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;87:1103–11. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alsberg H, Yang Z. Regulating bone formation via controlled scaffold degradation. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:923–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim EH, Heo CY. Current applications of adipose-derived stem cells and their future perspectives. World J Stem Cells. 2014;6:65–8. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashemibeni B, Esfandiari E, Razavi SH. Effect of TGF-β3 and BMP-6 growth factors on chondrogenic differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells in alginate scaffold. J Iran Anat Sci. 2010;8:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashemibeni B, Razavi S, Esfandiari E, Karbasi S, Mardani MO. Human cartilage tissue engineering from adipose-derived stem cells with BMP-6 in alginate scaffold. J Iran Anat Sci. 2010;8:117–29. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colter DC, Sekiya I, Prockop DJ. Identification of a subpopulation of rapidly self-renewing and multipotential adult stem cells in colonies of human marrow stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7841–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141221698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kassem M, Kristiansen M, Abdallah BM. Mesenchymal stem cells: Cell biology and potential use in therapy. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;95:209–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2004.pto950502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bischoff FZ, Hahn S, Johnson KL, Simpson JL, Bianchi DW, Lewis DE, et al. Intact fetal cells in maternal plasma: Are they really there? Lancet. 2003;361:139–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee RH, Kim B, Choi I, Kim H, Choi HS, Suh K, et al. Characterization and expression analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow and adipose tissue. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2004;14:311–24. doi: 10.1159/000080341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haghighat A, Akhavan A, Hashemi-Beni B, Deihimi P, Yadegari A, Heidari F. Adipose derived stem cells for treatment of mandibular bone defects: An autologous study in dogs. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2011;8(Suppl 1):S51–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashemibeni B, Esfandiari E, Sadeghi F, Heidary F, Roshankhah S, Mardani M, et al. An animal model study for bone repair with encapsulated differentiated osteoblasts from adipose-derived stem cells in alginate. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2014;17:854–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fulin C, Xiaobin C. Bone marrow-derived osteoblasts seeded into porous beta-tricalcium phosphate to repair segmental defect in canine's mandibula. J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2006;12:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, De Ugarte DA, Huang JI, Mizuno H, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4279–95. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, Ramay HR, Hauch KD, Xiao D, Zhang M. Chitosan-alginate hybrid scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3919–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohan BG, Suresh Babu S, Varma HK, John A. In vitro evaluation of bioactive strontium-based ceramic with rabbit adipose-derived stem cells for bone tissue regeneration. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2013;24:2831–44. doi: 10.1007/s10856-013-5018-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linero IM, Doncel A, Chaparro O. Proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in hydrogels of human blood plasma. Biomedica. 2014;34:67–78. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572014000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Appleford MR, Oh S, Oh N, Ong JL. In vivo study on hydroxyapatite scaffolds with trabecular architecture for bone repair. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;89:1019–27. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hosseinzadeh E, Davarpanah M, Hassanzadeh Nemati N, Tavakoli SA. Fabrication of a hard tissue replacement using natural hydroxyapatite derived from bovine bones by thermal decomposition method. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2014;5:23–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Backly RM, Zaky SH, Canciani B, Saad MM, Eweida AM, Brun F, et al. Platelet rich plasma enhances osteoconductive properties of a hydroxyapatite-ß-tricalcium phosphate scaffold (Skelite) for late healing of critical size rabbit calvarial defects. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42:e70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurashina K, Kurita H, Wu Q, Ohtsuka A, Kobayashi H. Ectopic osteogenesis with biphasic ceramics of hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate in rabbits. Biomaterials. 2002;23:407–12. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alam MI, Asahina I, Ohmamiuda K, Takahashi K, Yokota S, Enomoto S. Evaluation of ceramics composed of different hydroxyapatite to tricalcium phosphate ratios as carriers for rhBMP-2. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1643–51. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guda T, Walker JA, Pollot BE, Appleford MR, Oh S, Ong JL, et al. In vivo performance of bilayer hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration in the rabbit radius. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2011;22:647–56. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rathbone CR, Guda T, Singleton BM, Oh DS, Appleford MR, Ong JL, et al. Effect of cell-seeded hydroxyapatite scaffolds on rabbit radius bone regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102:1458–66. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim SJ, Chung YG, Lee YK, Oh IW, Kim YS, Moon YS. Comparison of the osteogenic potentials of autologous cultured osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells loaded onto allogeneic cancellous bone granules. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:303–10. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pourebrahim N, Hashemibeni B, Shahnaseri S, Torabinia N, Mousavi B, Adibi S, et al. A comparison of tissue-engineered bone from adipose-derived stem cell with autogenous bone repair in maxillary alveolar cleft model in dogs. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;42:562–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]