Abstract

Background:

Seasonal influenza epidemic occurs every year in Guangzhou, which can affect all age groups. Young children are the most susceptible targets. Parents can decide whether to vaccinate their children or not based on their own consideration in China. The aim of this study was to identify factors that are important for parental decisions on vaccinating their children against seasonal influenza based on a modified health belief model (HBM).

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Guangzhou, China. A total of 335 parents who had at least on child aged between 6 months and 3 years were recruited from women and children's hospital in Guangzhou, China. Each eligible subject was invited for a face-to-face interview based on a standardized questionnaire.

Results:

Uptake of seasonal influenza within the preceding 12 months among the target children who aged between 6 months and 36 months was 47.7%. Around 62.4% parents indicated as being “likely/very likely” to take their children for seasonal influenza vaccination in the next 12 months. The hierarchical logistic regression model showed that children's age (odds ratio [OR] =2.59, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.44–4.68), social norm (OR = 2.08, 95% CI: 1.06–4.06) and perceived control (OR = 2.96, 95% CI: 1.60–5.50) were significantly and positively associated with children's vaccination uptake within the preceding 12 months; children with a history of taking seasonal influenza vaccine (OR = 2.50, 95% CI: 1.31–4.76), perceived children's health status (OR = 3.36, 95% CI: 1.68–6.74), worry/anxious about their children influenza infection (OR = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.19–4.48) and perceived control (OR = 3.21, 95% CI: 1.65–6.22) were positively association with parental intention to vaccinate their children in the future 12 months. However, anticipated more regret about taking children for the vaccination was associated with less likely to vaccinate children within the preceding 12 months (OR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.08–0.52).

Conclusions:

The modified HBM provided a good theoretical basic for understanding factors associated with parents’ decisions on their children's vaccination against seasonal influenza.

Keywords: Children's Vaccination, Health Belief Model, Parents’ Perception and their Decision, Seasonal Influenza

INTRODUCTION

Seasonal influenza epidemics occurs every year.[1] It can affect all age groups. Young children are the most susceptible group.[2,3] It causes considerable disease burden in terms of excessive morbidity, mortality, and hospitalization yearly.[4] It was estimated that rates of hospitalization due to severe illness caused by influenza were 3 per 1000 for 6–23 months old children and 9 per 1000 for children younger than 6 months.[4] To control influenza and reduce disease burden of influenza, vaccination is one of the most effective ways.[5] Vaccinating young children is of particular importance because they can confer the protection to other age groups and subsequently could reduce influenza illness in the whole population.[6] To protect the most susceptible group, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention of China recommended that children aged 6–59 months is one of the priority groups for seasonal influenza vaccination.[7] Despite that influenza vaccination is not mandatory in China. Parents can decide whether to vaccinate their children or not based on their own consideration. Therefore, parents are the key decision-maker for their children's influenza vaccination. Moreover, a theoretical model can help us to identify the association with psychosocial factors and parental intention and decision. Based on a theoretical mode, it can also identify which factors are important for parents’ decision on vaccinating their children against seasonal influenza.

The health belief model (HBM) was initially designed by some psychologists Hochobaum, Rosenstock, and Kegels who worked for the US Public Health Service in 1950s[8] to study “the failure of people to accept disease preventives of screening tests for the early detection of asymptomatic disease.”[9] Initially, HBM was applied to predict treatment adherence and adoption of preventive health behaviors among patients.[10] Recently, HBM was commonly used for studying and predicting general healthy behavioral change and utilization of the health services,[11] which was also one of the most extensively used models for predicting preventive health behaviors.[8]

Health belief model consists of four main components.[8] This includes perceived susceptibility (e.g., the perceived probability/likelihood of contracting an infection), perceived severity (e.g., the perceived consequence of the infection), perceived benefits of the adopting the recommended behaviors and perceived barriers that could meet during taking action. Except these four main factors, the HBM also proposed that demographics could predict risk perceptions while “cues to action” (the perceived social pressure from significant others to perform the behavior) could further motivate behavioral change.[8,12] Recent revision on the HBM included perceived control as an additional component to predict the likelihood of behavioral change.[10]

Health belief model was developed based on the assumption that humans are rational decision-maker, and human's behavior is based on individual decision without being influenced by social factors.[13] However, humans are always individuals belonging to a social group.[14] Therefore, except for the original components of HBM, other factors are suggested to be included to improve the predictive power of the model.[10] Such as social norm which is an extension of “cues to action” defined as perceived social pressure from not only significant others but also general others to perform the behavior,[15] worry about contracting the infection,[16] anticipated regret due to the consequence of not performing the behavior,[10] and perceived control (or self-efficacy).

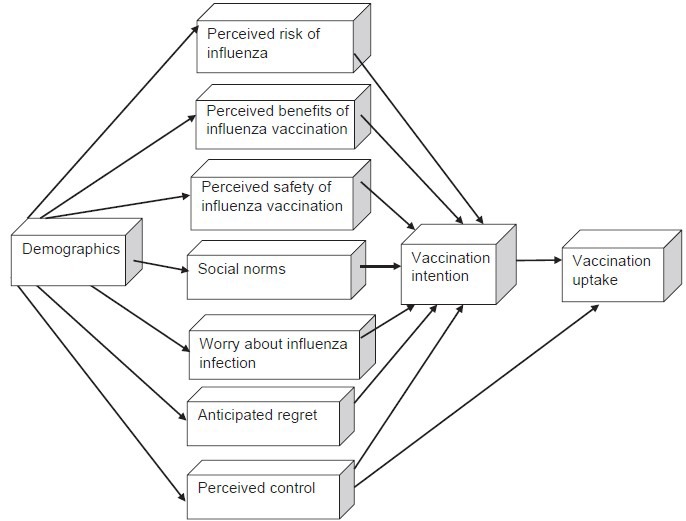

Figure 1 illustrated the framework of the modified HBM. The model proposes that demographics, perceived risk of influenza, perceived benefits of influenza vaccination, perceived safety of influenza vaccination, social norms, worry about influenza infection, anticipated regret, perceived control were composed of the predictors of the model. These variables were linked to the vaccination intention and then associated with vaccination uptake. Perceived control should be able to predict both vaccination intention and vaccination uptake. To identify factors that influenced parents’ intention to take their children for seasonal influenza vaccination and actual behavior of vaccinating their children against seasonal influenza on the basis of the modified HBM.

Figure 1.

The framework of the modified health belief model.

Health belief model was an appropriate model for identifying what factors could affect parents’ perceptions and decisions on their children's vaccination against seasonal influenza.[17] However, due to the limitations of HBM model, social norms and emotional factors (worry/anxious, anticipated regret) should be included as additional factors in the original HBM to improve the prediction power of HBM for parental decision on children's vaccination against seasonal influenza. Based on the above introduction, except for perceived susceptibility of influenza, perceived severity of influenza, perceived benefits of influenza vaccination, perceived lower barriers of influenza vaccination, certain demographics, social norms, anticipated regret, worry about influenza infection and perceived control were associated with parental acceptance for child influenza vaccination. Some studies have been conducted based on HBM outside China. However, in China, relevant studies were few and most of the available ones were conducted without theoretical basics.

METHODS

Subject recruitment

This was a cross-sectional study. Parents who took their children for regular body check during May 1, 2013 and July 1, 2013 in the Liwan District Women and Children's Hospital, Guangzhou, China were recruited in the study. Other inclusion criteria included: (a) parents (either fathers or mothers) whose children were aged between 6 months and 3 years; (b) parents should be either Cantonese- or Mandarin-speaking; and (c) being willing to participate in the survey. Exclusion criteria included the adults who took the children for the body check were not parents of the children or parents with linguistic or intellectual difficulties to complete an interview.

All the identifiers and the interviewers were trained to be familiar with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the content of questionnaire and skills of asking questions before conducting the pilot study. The interviewers discussed the problems encountered in the pilot interview and were retrained before the formal study started. And then each eligible subject was invited to complete a face-to-face interview based on a standardized questionnaire. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster and Guangzhou Liwan District Women and Children's Hospital.

This study targeted the parents with healthy children aged between 6 months and 3 years. The first reason was that children of this age group were in high risk of contracting seasonal influenza. Second, convenient sampling was used due to limited time and resources (less human resources and money). And then, this hospital mainly provided regular physical examination for young children.

Pilot study

Before the formal study, a pilot study was conducted in April 2013 to test the length, comprehensibility, content and face acceptability of the questionnaire. All interviewers were trained before the pilot study started. A standardized questionnaire constructed based on the one used in a similar survey conducted in Hong Kong. The questionnaire comprised of five sections including Part 1, the children's demographics; Part 2, information communication; Part 3, perceptions regarding seasonal influenza and influenza vaccination; Part 4, vaccination intention and vaccination behaviors; Part 5, parental demographics. Each questionnaire required enough time to be completed in each face-to-face interview. The subjects generally had good understanding about the questions in the questionnaire and were willing to answer all questions. After completing the pilot study, minor revisions were made on several questions without changing the meaning of the questions on the basic of respondents’ feedbacks and under the discussion of the research team.

Sample size calculation

Due to lack of data about the influenza vaccination uptake in children in Guangzhou, the vaccination uptake against seasonal influenza among children in Guangzhou was estimated based on the data of Chongqing city,[18] a municipality located in Southern China directly managed by the Chinese central government with a comparable economic level and health care system to that in Guangzhou. Rate of seasonal influenza vaccination uptake was estimated to be 35.8% and 34.2% among children aged below 2 years and aged between 3 years and 6 years, respectively, in Chongqing, China. Accordingly, we estimated that the uptake rate of seasonal influenza vaccine among the target children in Guangzhou was 35%. To detect an association of odds ratio (OR) =1.5 between risk perception of seasonal influenza and vaccination uptake with an error of 0.05 and a power of 80%, the required sample size was estimated to be 225. To allow for a response rate of around 70%, we targeted around 330 subjects in the study.

Study measures

Questionnaire was developed based on the one used in a similar survey conducted in Hong Kong to investigate parents’ decision-making regarding children's vaccination against seasonal influenza. The final questionnaire was determined after the pilot study. Before the interview started, participants were given an information sheet. The participants were informed about the objectives of this study, the risk of participating in the study, the confidentiality of personal information and the right of freely withdrawing from the survey. After reading the information sheet, participants were asked about their willingness to participate in the survey and asked to sign in a consent form if they decided to participate in the survey.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses aimed to examine the factors associated with two major outcomes, parental intention to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza over the next 12 months and children's vaccination uptake against seasonal influenza within the preceding 12 months. SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., USA) was employed to analyze the data. First, descriptive analyses were used to calculate the proportions of each variable. Then, univariate analysis was conducted to examine the association between demographic and perception variables and two primary outcomes. Significant demographic variables associated with the two primary outcomes in the univariate analyses and all parental perception variables were entered into two hierarchical logistic regression models, respectively, for the two primary outcomes. In the hierarchical models, based on the modified HBM, independent variables were parental intention over next 12 months and children's uptake of influenza vaccination over past 12 months, respectively, The outcome variables were dichotomized as binary variables for the logistic regression models. For both models, in the first block, significant demographic characteristics were included; in the second block, perceived susceptibility of influenza, perceived severity of influenza, perceived benefits of influenza vaccination, perceived children's health status entered into the second block, while worry/anxious about their children contracting influenza, anticipated regret feeling, social norms regarding influenza vaccination, perceived control were included in the third block. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Totally, 335 participants were invited for the interview, of which 305 agreed to participate, and finally 298 participants successfully completed the interview. The response rate was 89.0% (298/335). Most (95.0%) children of whom the parents participated in the interview were aged between 6 months and 36 months while 5.0% of the children were aged between 39 months and 48 months. Although children aged between 39 months and 48 months were not eligible based on the inclusion criteria in my original proposal, parents of these children were not excluded from analysis because they were also regarded as a priority group of seasonal influenza vaccination. Overall, 83.9% respondents reported to have had only one child in their family. The mean age of target children was 20.3 months (ranged between 6 months and 48 months). 64.1% of the target children were aged between 6 months and 24 months, and 35.9% children were aged between 24 months and 48 months. This study only focused on children who presented in the hospital during the interview. Most children (95.3%) had no chronic disease, and the remaining had chronic conditions such as heart disease and asthma. Around 34.6% parents thought that their children's health was very good or excellent, while 12.8% perceived their children's health to be “not so good.”

Overall, 78.2% of the respondents were female; almost all (99.7%) were married parents; 78.9% of the parents were aged between 18 years and 34 years and 21.1% of them were aged 35–54 years; 31.9% of them were Guangzhou natives while 40.6% were born in other cities of Guangdong province and 27.2% were born outside of Guangdong; 63.8% of them obtained secondary or equivalent education while 31.9% had tertiary or above education obtainment; most parents (64.8%) were being employed; household monthly income were less than CNY 10,000 in most families (61.7%); finally, around 42.3% of the participants indicated that mothers were the primary decision-maker for children's immunization while 39.9% indicated that fathers and mothers made shared decision 12.8% indicated that there was no difference in decision-making between fathers and mothers, and only 4.0% said that fathers were the primary decision-maker.

Experience of influenza, vaccination uptake among children and parental intention to vaccinate children against seasonal influenza

Overall, 51.3% of the parents reported that their children had been vaccinated against seasonal influenza in the past. Children with experience of influenza vaccination in the past were associated with higher parental intention to vaccinate children in the next 12 months (χ2 = 21.12, P < 0.001) [Table 1]. 47.0% indicated that their children had received seasonal influenza vaccine within the preceding 12 months. Around 60.1% of the parents indicated that they had the intention to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza over the next 12 months; 62.4% indicated that they would be “likely/very likely/certainly” to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza over the next 12 months. Around 11.1% of the parents indicated that their children have been infected influenza. Among the parents, only 10.7% of them reported themselves to be vaccinated against seasonal influenza in the past 3 years.

Table 1.

Associations between demographics and parental intention to vaccinate children over the next 12 months (n = 298)

| Items | Parental intention to vaccinate their children (n (%)) | χ2 (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Never/very unlikely/unlikely/evens | Likely/very likely/certain | ||

| Children demographics | |||

| Age group (months) | |||

| 6–24 | 74 (67.3) | 115 (61.8) | 0.89 (0.35) |

| >24 | 36 (32.7) | 71 (38.2) | |

| Child number | |||

| One | 87 (84.5) | 162 (90.5) | 2.31 (0.13) |

| Two or above | 16 (15.5) | 17 (9.5) | |

| Child disease history | |||

| None | 105 (97.2) | 177 (95.7) | (0.75) Fisher's exact test |

| Yes | 3 (2.8) | 8 (4.3) | |

| Parent's demographic | |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 84 (76.4) | 147 (79.0) | 0.29 (0.59) |

| Male | 26 (23.6) | 39 (21.0) | |

| Age group (years) | |||

| 18–34 | 88 (80.0) | 145 (78.0) | 0.17 (0.68) |

| ≥35 | 22 (20.0) | 41 (22.0) | |

| Birth place | |||

| Guangzhou city | 35 (32.1) | 60 (32.3) | 1.89 (0.39) |

| Guangdong province | 49 (45.0) | 71 (38.2) | |

| Other cities in China (out of Guangdong)/other countries | 25 (22.9) | 55 (29.6) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Secondary school or below | 73 (66.4) | 127 (68.6) | 0.17 (0.69) |

| Tertiary or above | 37 (33.6) | 58 (31.4) | |

| Present occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 42 (38.2) | 62 (33.3) | 0.71 (0.40) |

| Employed | 68 (61.8) | 124 (66.7) | |

| Household income (CNY) | |||

| <10,000 | 80 (72.7) | 102 (54.8) | 9.34 (0.002) |

| 10,000–20,000 | 30 (27.3) | 84 (45.2) | |

| Decision-maker | |||

| Father | 4 (3.7) | 8 (4.3) | 3.24 (0.36) |

| Mother | 48 (44.4) | 77 (41.4) | |

| Both of parents decide it | 38 (35.2) | 81 (43.5) | |

| The same | 18 (16.7) | 20 (10.8) | |

| Experience of influenza and influenza vaccination | |||

| VA1. Have you ever received seasonal influenza vaccine at any time in past 3 years? | |||

| Yes | 13 (11.9) | 19 (10.2) | 0.21 (0.65) |

| No | 96 (88.1) | 167 (89.8) | |

| VA1b. Did your child ever receive seasonal influenza vaccine in the past | |||

| Yes | 38 (36.2) | 114 (64.4) | 21.12 (<0.001) |

| No | 72 (63.8) | 63 (35.6) | |

| VA2. Has your child ever been diagnosed as having influenza in the past? | |||

| Yes | 10 (9.1) | 23 (12.4) | 0.75 (0.39) |

| No | 100 (90.9) | 163 (87.6) | |

The associations between demographics, experience and influenza vaccination uptake among children

Table 2 showed the associations between demographics (parents and children), experience of influenza and influenza vaccination and children's vaccination uptake against seasonal influenza within the preceding 12 months. It was shown that except for children's age and household income and parental experience of influenza vaccination in past 3 years, other demographics and experience were not significantly associated with children's influenza vaccination uptake [Table 2]. Compared with the nonvaccinated group, children who received influenza vaccine within the preceding 12 months were more likely to be older (χ2 = 9.46, P = 0.002), more likely to be from families with higher household income (χ2 = 6.44, P = 0.011), and their parents were more likely to be vaccinated against seasonal influenza in the past 3 years (χ2 = 4.66, P = 0.03) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Associations between demographics and children's vaccination uptake against seasonal influenza (n = 298)

| Items | Child received influenza vaccine over the past 12 months (n (%)) | χ2 (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated | Nonvaccinated | ||

| Children demographic | |||

| Age group (months) | |||

| 6–24 | 78 (55.7) | 104 (73.2) | 9.46 (0.002) |

| >24 | 62 (44.3) | 38 (26.8) | |

| Disease history of children | |||

| None | 135 (97.1) | 135 (95.7) | (0.75) Fisher's exact test |

| Yes | 4 (2.9) | 6 (4.3) | |

| Child number | |||

| One | 115 (85.8) | 121 (90.3) | 1.28 (0.258) |

| Two or above | 19 (14.2) | 13 (9.7) | |

| Parent's demographic | |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 107 (76.4) | 113 (79.6) | 0.41 (0.523) |

| Male | 33 (23.6) | 29 (20.4) | |

| Age group (years) | |||

| 18–34 | 107 (76.4) | 113 (79.6) | 0.41 (0.523) |

| 35–54 | 33 (23.6) | 29 (20.4) | |

| Birth place | |||

| Guangzhou | 43 (30.9) | 47 (33.1) | 0.62 (0.735) |

| Other cities in Guangdong | 56 (40.3) | 60 (42.3) | |

| Other cities in China (out of Guangdong)/other countries | 40 (28.8) | 35 (24.6) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Secondary school level or lower | 94 (67.1) | 96 (68.1) | 0.03 (0.866) |

| Tertiary or above | 46 (32.9) | 45 (31.9) | |

| Present occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 45 (32.1) | 54 (38.0) | 1.07 (0.301) |

| Employed | 95 (67.9) | 88 (62.0) | |

| Household income (CNY) | |||

| <10,000 | 75 (53.6) | 97 (68.3) | 6.44 (0.011) |

| ≥10,000 | 65 (46.6) | 45 (31.7) | |

| Decision-maker | |||

| Father | 5 (3.6) | 6 (4.3) | 0.84 (0.841) |

| Mother | 62 (44.3) | 57 (40.4) | |

| Both of them decide it | 54 (38.6) | 61 (43.3) | |

| The same | 19 (13.6) | 17 (12.1) | |

| Experience of influenza and influenza vaccination | |||

| VA1. Have you ever received seasonal influenza vaccine at any time in past 3 years? | |||

| Yes | 21 (15.1) | 10 (7.0) | 4.66 (0.03) |

| No | 118 (84.9) | 132 (93.0) | |

| VA2. Has your child ever been diagnosed as having influenza in the past? | |||

| Yes | 17 (12.1) | 15 (10.6) | 0.18 (0.68) |

| No | 123 (87.9) | 127 (89.4) | |

The associations between demographics, experience and parents’ intention to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza over the next 12 months

Table 1 was about the associations between demographics, experience of influenza and influenza vaccination and parents’ intention to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza over the next 12 months. It was shown that only household income and children's past seasonal influenza vaccination uptake were significantly associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children. Parents with higher household income (χ2 = 9.34, P = 0.002) and whose children had received seasonal influenza vaccine in the past (χ2 = 21.12, P < 0.001) had higher intention to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza over the next 12 months [Table 1].

Parental perceptions and vaccination uptake against seasonal influenza among children

Table 3 showed the associations between parent perceptions and children's influenza vaccination uptake over the past 12 months. The univariate analysis showed that worry about child influenza infection, anxiety, perceived child susceptibility to seasonal influenza, perceived severity of child influenza infection, anticipated regret for not vaccinating children and perceived child health status were not significantly associated with children's vaccination uptake within the preceding 12 months [Table 3]. Perceived vaccine safety (χ2 = 5.55, P = 0.018), perceived benefit of influenza vaccination (χ2 = 7.35, P = 0.007) and perceived control (χ2 = 24.69, P < 0.001) were positively associated with children's vaccination uptake within the preceding 12 months [Table 3]. The three items for measuring social norms including perceived importance of following other known parents’ behavior to vaccinate their children (χ2 = 20.06, P < 0.001), family or friends’ advice on vaccinating children (χ2 = 17.10, P < 0.001) and most parents’ behaviors to vaccinate their children (χ2 = 12.19, P < 0.001) were all positively associated with children's vaccination uptake within the preceding 12 months [Table 3]. Anticipated regret for the negative consequence due to vaccinating children was negatively associated with children's vaccination uptake within the preceding 12 months (χ2 = 25.46, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Univariate association between parental perceptions and children's vaccination uptake against seasonal influenza over the past 12 months (n = 298)

| Items (parental perception) | Children's vaccination uptake over the past 1-year (n (%)) | χ2 (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated | Nonvaccinated | ||

| BF1. In the past 1-week, have you worried that your child would catch seasonal influenza? (worry) | |||

| Not at all | 54 (38.6) | 50 (35.2) | 0.376 (0.828) |

| Somewhat worried | 47 (33.6) | 49 (34.5) | |

| Worries me a lot/all the time | 39 (27.9) | 43 (30.3) | |

| BF3. When you think about the possibility of your child to contract seasonal influenza, do you feel: Anxiety? | |||

| Not at all | 9 (6.4) | 12 (8.6) | 4.639 (0.098) |

| A little bit anxious | 30 (21.4) | 44 (31.4) | |

| Somewhat anxious/very anxious | 101 (72.1) | 84 (60.0) | |

| BF2. If you do not vaccinate your child against seasonal influenza, how likely do you think it is that she/he will catch seasonal influenza over the coming influenza season? (perceived susceptibility) | |||

| Very unlikely/unlikely/evens | 83 (59.3) | 94 (66.2) | 1.44 (0.230) |

| Likely/very likely | 57 (40.7) | 48 (33.8) | |

| BF4. If you do not to vaccinate your child against seasonal influenza, what do you think is the chance that your child will be seriously ill if he/she gets seasonal influenza? (perceived severity) | |||

| Very unlikely/unlikely/evens | 94 (67.6) | 98 (69.0) | 0.06 (0.803) |

| Likely/very likely | 45 (32.4) | 44 (31.0) | |

| BF5. How safe do you think the seasonal influenza vaccine is for your child? (perceived vaccine safety) | |||

| Not safe/unsure | 71 (51.1) | 91 (65.0) | 5.55 (0.018) |

| Safe | 68 (48.9) | 49 (35.0) | |

| BF6a. I believe that vaccinating my child against seasonal influenza can reduce his/her risk of getting seasonal influenza (perceived benefits of influenza vaccination) | |||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/evens | 29 (20.7) | 50 (35.2) | 7.35 (0.007) |

| Agree/strongly agree | 111 (79.3) | 92 (64.8) | |

| BF6d. If other parents i know have their children vaccinated against seasonal influenza, it will encourage me to do the same (social norms) | |||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/evens | 49 (35.0) | 87 (61.7) | 20.06 (<0.001) |

| Agree/strongly agree | 91 (65.0) | 54 (38.3) | |

| BF6i. If my families and friends though that i should take child to vaccinate, I though I should listen to their advice (social norms) | |||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/evens | 47 (33.6) | 82 (58.2) | 17.10 (<0.001) |

| Agree/strongly agree | 93 (66.4) | 59 (41.8) | |

| BF6k. If most parents bring their child to take seasonal influenza vaccination, I feel that I should also do so (social norms) | |||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/evens | 41 (29.3) | 70 (49.6) | 12.19 (<0.001) |

| Agree/strongly agree | 99 (70.7) | 71 (50.4) | |

| BF7. If you vaccinate your child against seasonal influenza, but your child subsequently still got influenza, will you feel that you would regret your decision? (anticipated regret for vaccinating children) | |||

| Definitely not regret | 86 (61.4) | 51 (35.9) | 25.46 (<0.001) |

| Slightly regret | 44 (31.4) | 54 (38.0) | |

| Moderately regret/extremely | 10 (7.1) | 37 (26.1) | |

| BF8. If you do not vaccinate your child against seasonal influenza and your child subsequently got influenza, will you feel that you would regret your decision not to have them vaccinated? (anticipated regret for not vaccinating children) | |||

| Definitely not regret | 41 (29.3) | 34 (23.9) | 1.14 (0.556) |

| Slightly regret | 62 (44.3) | 70 (49.3) | |

| Moderately regret/extremely regret | 37 (26.4) | 38 (26.8) | |

| BF9. If you do try, how difficult do you think it is for you to take your child for seasonal influenza vaccination in the coming 12 months? (perceived control) | |||

| Very difficult/difficult/evens | 27 (19.3) | 67 (47.2) | 24.69 (<0.001) |

| Confident/very confident | 113 (80.7) | 75 (52.8) | |

| CD4. Perceived healthy status of children | |||

| Excellent good/very good | 47 (33.6) | 50 (35.2) | 0.13 (0.936) |

| Good | 75 (53.6) | 73 (51.4) | |

| Fair/poor | 18 (12.9) | 19 (13.4) | |

Associations between parental perceptions and their intention to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza over the next 12 months

The univariate analysis showed that all parental perceptions except for worry about child influenza infection and anticipated regret for vaccinating children were significantly associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children over the next 12 months [Table 4]. Specifically, perceived child susceptibility to influenza infection (χ2 = 8.82, P = 0.003), perceived severity of child influenza infection (χ2 = 7.72, P = 0.005.), anxiety about child influenza infection (χ2 = 16.26, P < 0.001), perceived vaccine safety (χ2 = 6.75, P = 0.009), anticipated regret for not vaccinating children (χ2 = 9.22, P = 0.010), perceived control (χ2 = 36.75, P < 0.001), perceived poorer child health status (χ2 = 10.12, P = 0.006) and perceived benefit of influenza vaccination (χ2 = 26.31, P < 0.001) were positively associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza over the next 12 months [Table 4]. All the three items for measuring social norms were also significantly and positively associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza over the next 12 months [Table 4].

Table 4.

Univariate association between parental perception and parental intention to vaccinate children against seasonal influenza over the next 12 Months (n = 298)

| Items (parental perception) | Parental intention to vaccinate their children over the next 12 months (n (%)) | χ2 (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Never/very unlikely/unlikely/evens | Likely/very likely/certain | ||

| BF1. In the past 1-week, have you worried that your child would catch seasonal influenza? (Worry) | |||

| Not at all | 47 (42.7) | 59 (31.7) | 3.84 (0.146) |

| Somewhat worried | 33 (30.0) | 71 (38.2) | |

| Worries me a lot/all the time | 30 (27.3) | 56 (30.1) | |

| BF2. If you do not to vaccinate your child against seasonal influenza, how likely do you think it is that she/he will catch seasonal influenza over the coming influenza season? (perceived susceptibility) | |||

| Very unlikely/unlikely | 80 (72.7) | 103 (55.4) | 8.82 (0.003) |

| Likely | 30 (27.3) | 83 (44.6) | |

| BF3. When you think about the possibility of your child to contract seasonal influenza, do you feel: Anxiety? | |||

| Not at all | 13 (11.8) | 8 (4.3) | 16.26 (<0.001) |

| A little anxious | 39 (35.5) | 38 (20.7) | |

| Somewhat anxious/very anxious | 58 (52.7) | 138 (75.0) | |

| BF4. If you do not to vaccinate your child against seasonal influenza, what do you think is the chance that your child will be seriously ill if he/she gets seasonal influenza? (perceived severity) | |||

| Very unlikely/unlikely | 85 (78) | 116 (62.4) | 7.72 (0.005) |

| Likely/very likely | 24 (22.0) | 70 (37.6) | |

| BF5. How safe do you think the seasonal influenza vaccine is for your child? (perceived vaccine safety) | |||

| Not safe/unsure | 73 (68.2) | 98 (52.7) | 6.75 (0.009) |

| Safe | 34 (31.8) | 88 (47.3) | |

| BF6a. I believe that vaccinating my child against seasonal influenza can reduce his/her risk of getting seasonal influenza (perceived benefit of influenza vaccination) | |||

| Definitely disagree/disagree/evens | 50 (45.5) | 33 (17.7) | 26.31 (<0.001) |

| Agree/definitely agree | 60 (54.5) | 153 (82.3) | |

| BF6d. If other parents i know have their children vaccinated against seasonal influenza, then it will encourage me to do the same (social norms) | |||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/evens | 67 (60.9) | 70 (37.8) | 14.76 (<0.001) |

| Agree/strongly agree | 43 (39.1) | 115 (62.2) | |

| BF6i. If my families and friends though that i should take my child to vaccinate, i thought i should listen to their advice (social norms) | |||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/evens | 60 (54.5) | 70 (37.8) | 7.81 (0.005) |

| Agree/strongly agree | 50 (45.5) | 115 (62.2) | |

| BF6k. If most parents bring their child to take seasonal influenza vaccination, i feel that i should also do so (social norms) | |||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/evens | 51 (46.4) | 64 (34.6) | 4.02 (0.045) |

| Agree/strongly agree | 59 (53.6) | 121 (65.4) | |

| BF7. If you vaccinate your child against seasonal influenza, but your child subsequently still got influenza, will you feel that you would regret your decision? (anticipated regret for vaccinating children) | |||

| Definitely not regret | 46 (41.8) | 96 (51.6) | 3.37 (0.186) |

| Slightly regret | 40 (36.4) | 62 (33.3) | |

| Moderately regret/extremely regret | 24 (21.8) | 28 (15.1) | |

| BF8. If you do not vaccinate your child against seasonal influenza and your child subsequently got influenza, will you feel that you would regret your decision not to have them vaccinate? (anticipated regret for not vaccinating children) | |||

| Definitely not regret | 35 (31.8) | 41 (22.0) | 9.22 (0.010) |

| Slightly regret | 56 (50.9) | 84 (45.2) | |

| Moderately regret/extremely regret | 19 (17.3) | 61 (32.8) | |

| BF9. If you do try, how difficult do you think it is for you to take your child for seasonal influenza vaccination in the coming 12 months? (perceived control) | |||

| Very difficult/difficult/evens | 61 (55.5) | 39 (21.0) | 36.75 (<0.001) |

| Confident/very confident | 49 (44.5) | 147 (79.0) | |

| CD4. Perceived healthy status of child | |||

| Excellent good/very good | 50 (45.9) | 52 (28.0) | 10.12 (0.006) |

| Good | 49 (45.0) | 106 (57.0) | |

| Fair/poor | 10 (9.2) | 28 (15.1) | |

Factors associated with children's vaccination uptake: The multivariate analysis

To examine the factors associated with children's vaccination uptake against seasonal influenza within the preceding 12 months, significant demographic variables and all parental perception variables were entered into the hierarchical logistic regression model. The multivariate logistic regression model showed that after mutually adjusted for other variables, children's age (OR = 2.59, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.44–4.68), social norms (OR = 2.08, 95% CI: 1.06–4.06) and perceived control (OR = 2.96, 95% CI: 1.60–5.50) were positively associated with children's influenza vaccination uptake within the preceding 12 months while anticipated regret (moderate/extremely regret) about the negative consequence (e.g., getting an influenza) due to vaccinating children against seasonal influenza was negatively associated with children's influenza vaccination uptake within the preceding 12 months (OR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.08–0.52) [Table 5].

Table 5.

OR for the associations between demographics, parental perceptions and children's vaccination uptake against seasonal influenza over the past 12 months (n = 298)

| Items | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI of OR | OR | 95% CI of OR | OR | 95% CI of OR | |

| Block1 | ||||||

| Age of child (months) | ||||||

| 6–24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| >24 | 2.30† | 1.37, 3.87 | 2.47† | 1.44, 4.22 | 2.59* | 1.44, 4.68 |

| Monthly household income (CNY) | ||||||

| <10,000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≥10,000 | 1.80* | 1.08, 2.98 | 1.50 | 0.89, 2.55 | 1.65 | 0.91, 3.02 |

| Parental experience of influenza vaccination in past 3 years | ||||||

| None | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Have experience | 2.72* | 1.20, 6.19 | 2.89* | 1.23, 6.77 | 2.44 | 0.98, 6.05 |

| Block 2 | ||||||

| Perceived health status of children | ||||||

| Excellent | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Good | 1.02 | 0.58, 1.79 | 1.38 | 0.73, 2.59 | ||

| Fair/poor | 0.90 | 0.39, 2.06 | 1.35 | 0.54, 3.36 | ||

| Perceived susceptibility | ||||||

| Unlikely | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Likely | 1.15 | 0.67, 1.99 | 1.00 | 0.54, 1.85 | ||

| Perceived severity | ||||||

| Unlikely | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Likely | 0.92 | 0.52, 1.61 | 0.70 | 0.37, 1.30 | ||

| Perceived vaccine safety | ||||||

| No safety | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Safety | 1.50 | 0.88, 2.56 | 1.31 | 0.73, 2.35 | ||

| Perceived benefit of influenza vaccination | ||||||

| Disagree | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Agree | 1.88* | 1.01, 3.49 | 0.94 | 0.45, 1.96 | ||

| Block 3 | ||||||

| Social norms | ||||||

| Disagree | 1 | |||||

| Agree | 2.08* | 1.06, 4.06 | ||||

| Emotion | ||||||

| Not worry/not anxious | 1 | |||||

| Worry/anxious | 1.40 | 0.76, 2.58 | ||||

| Perceived control | ||||||

| Difficult | 1 | |||||

| Easily/very easily | 2.96† | 1.60, 5.50 | ||||

| Anticipated regret for not vaccinating children | ||||||

| Not regret | 1 | |||||

| Slightly regret | 0.63 | 0.31, 1.27 | ||||

| Moderately/extremely regret | 0.58 | 0.25, 1.33 | ||||

| Anticipated regret for vaccinating children | ||||||

| Not regret | 1 | |||||

| Slightly regret | 0.66 | 0.35, 1.25 | ||||

| Moderate/extremely regret | 0.21† | 0.08, 0.52 | ||||

*P < 0.05, †P < 0.01, OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

Factors associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children over the next 12 months

Similarly, factors associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children over the next 12 months were examined using the hierarchical logistic regression models by entering the significant demographic variables identified in the univariate analyses and all the parental perception variables as independent variables.

The results of Table 6 showed that after being fully adjusted, only children's past influenza vaccination (OR = 2.50, 95% CI: 1.31–4.76), perceiving that children's health status was good vs. excellent (OR = 3.36, 95% CI: 1.68–6.74), worry/anxiety about child influenza infection (OR = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.19–4.48) and perceived control (OR = 3.21, 95% CI: 1.65–6.22) were positively associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children over the next 12 months.

Table 6.

OR for likely to vaccination: By children and parent demographics and modified health belief model variables (n = 298)

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI of OR | OR | 95% CI of OR | OR | 95% CI of OR | |

| Block 1 | ||||||

| Age of child (months) | ||||||

| 6–24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| >24 | 0.97 | 0.55, 1.73 | 1.11 | 0.60, 2.06 | 1.23 | 0.64, 2.38 |

| Monthly household income (CNY) | ||||||

| <10,000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≥10,000 | 2.08† | 1.20, 3.60 | 1.84* | 1.01, 3.36 | 1.79 | 0.92, 3.49 |

| Parental experience of influenza vaccination in past 3 years | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.85 | 0.37, 2.00 | 0.91 | 0.37, 2.25 | 0.90 | 0.33, 2.45 |

| Child's past history of influenza vaccination | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 3.42‡ | 1.97, 5.94 | 3.26‡ | 1.81, 5.87 | 2.50† | 1.31, 4.76 |

| Block 2 | ||||||

| Perceived health status of children | ||||||

| Excellent | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Good | 2.34† | 1.27, 4.31 | 3.36† | 1.68, 6.74 | ||

| Fair/poor | 2.16 | 0.82, 5.66 | 2.12 | 0.75, 6.00 | ||

| Perceived susceptibility | ||||||

| Unlikely | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Likely | 1.62 | 0.88, 2.99 | 1.20 | 0.61, 2.34 | ||

| Perceived severity | ||||||

| Unlikely | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Likely | 2.16* | 1.14, 4.12 | 1.53 | 0.75, 3.10 | ||

| Perceived safety of vaccine | ||||||

| No safety | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Safety | 1.35 | 0.75, 2.45 | 1.27 | 0.67, 2.43 | ||

| Perceived benefit of influenza vaccination | ||||||

| Disagree | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Agree | 2.01* | 1.06, 3.80 | 1.40 | 0.67, 2.91 | ||

| Block 3 | ||||||

| Social norms | ||||||

| Disagree | 1 | |||||

| Agree | 1.81 | 0.90, 3.66 | ||||

| Emotion | ||||||

| Not worry/anxious | 1 | |||||

| Worry/anxious | 2.31* | 1.19, 4.48 | ||||

| Perceived control | ||||||

| Difficult | 1 | |||||

| Easily/very easily | 3.21† | 1.65, 6.22 | ||||

| Anticipated regret for not vaccinating children | ||||||

| Not regret | 1 | |||||

| Slightly regret | 0.86 | 0.40, 1.84 | ||||

| Moderately/extremely regret | 1.82 | 0.75, 4.44 | ||||

| Anticipated regret for vaccinating children | ||||||

| Not regret | 1 | |||||

| Slightly regret | 1.33 | 0.62, 2.76 | ||||

| Moderate/extremely regret | 1.01 | 0.40, 2.52 | ||||

*P < 0.05, †P < 0.01, ‡P < 0.001. OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Health belief model was one of the broadly used models to predict human preventive behavior,[8] which has been used to study factors associated with parents’ decisions on children's vaccination against seasonal influenza in other countries.

Demographics

Demographics include gender, age, race, education level, employment, inhabitancy, birth-place, income, marriage status, economic status, past history of influenza vaccination. The HBM proposes that demographics influence on behavioral intention through their effects on perceived risk of the disease.[8]

Parents’ demographics

A cross-sectional study conducted in the UK found that Asian parents were more likely to take their children for the vaccination than the Caucasians.[19] Tuma et al.[20] reported that caregivers with higher education level were more likely to vaccinate their children. A cross-sectional study conducted in Taiwan found that parental demographics including their age, educational level, employment status, place of residence were all significant predictors of influenza vaccination.[21] Of the 298 subjects, most subjects were female. The range of age was 18–54 years and most of them were young parents (aged < 35 years). More than half of the parents obtained at least secondary education and approximate 65% currently had employment. However, in my study, parental age, sex, education level, current employment status were not significantly associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children or children's actual vaccination uptake. This was inconsistent with the findings of a study conducted in Taiwan[21] and a study conducted in the USA.[17] The possible reason for these inconsistent findings might be cultural difference among the three areas. Household income was significantly and positively associated with parental intention to vaccinate children over the next 12 months and children's vaccination uptake within the preceding 12 months. This finding was consistent with the findings of the study conducted in Chongqing city.[18] However, the significant associations disappeared after adjusting for parental perceptions in the multivariate logistic regression models, suggesting that the associations between family income and parental intention or children's vaccination uptake might be mediated by parental perceptions regarding seasonal influenza and influenza vaccination.[22] For parental experience of seasonal influenza vaccination, it was not significantly associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children in the next year. That was also not consistent with a previous study conducted in the USA.[17] One possible reason for that was the uptake rate of seasonal influenza vaccination in parents was very low. Only 10.7% parents had received seasonal influenza vaccine in past 3 years. Low uptake rate might not have enough power to detect or might underestimate the relationship between past-experience and parental intention. However, parental history of influenza vaccination was significantly associated with children's vaccination uptake. After fully adjusted in the third block, parents’ experience of influenza vaccination became insignificantly associated with their children's vaccination uptake (OR = 2.44, 95% CI: 0.98–6.05). It suggested that parents’ past influenza vaccination might have an indirect effect on parents’ future behavior to vaccinate their children. Another possible explanation for this change may be due to the small sample size. If the sample size were larger, the 95% CI might be narrower and we might get the significant result.

Children demographic

Age of children was significantly associated with their reported vaccination uptake in my study, with older children being more likely to be vaccinated within the preceding 12 months. This association remained significant even after adjusting for parental perceptions in the multivariate logistic regression model. This indicated that age of children might have a direct effect on their actual vaccination uptake or an effect not mediated by parental perceptions. A cross-sectional study conducted in Taiwan found that child demographics including chronic conditions, past history of hospitalization and influenza infection were all significant predictor of influenza vaccination.[21] However, in the study, 3.7% children had chronic disease. The chronic diseases of children were not significantly associated with the parental intention and behavior. A possible explanation was few children with chronic disease collected in my study, so that the effect on outcome might not be detected. Another possible explanation was that these parents would regard children with chronic disease might not suitable for vaccination against seasonal influenza. They might consider more about the adverse reactions and harmful influences on their children's health. But it is difficult to prove this hypothesis in this study, and it could be investigated in future study. Parents whose children were once vaccinated against seasonal influenza in the past had higher intention to vaccinate their children in the future. This finding was consistent with previous studies.[21,23,24] The association between past child influenza vaccination uptake and parental intention to vaccinate children remained significant even after adjusted parental perception variables though the effect size reduced, indicating that past child influenza vaccination uptake had a direct effect on parental intention. A possible explanation was that experience of child vaccination uptake would increase the parents’ confidence to vaccinate their children in the future. For example, parents may have learned how to access the influenza vaccination services.

Perceived risk of seasonal influenza

Perceived susceptibility of influenza

Parental decisions on children's influenza vaccination were primarily determined by their beliefs and perceptions regarding influenza and influenza vaccination.[17] It was found that perceived susceptibility of influenza infection was positively associated with vaccination intention but perceived severity of influenza was not.[25] In my study, perceived susceptibility of influenza was not significantly associated with children's influenza uptake (χ2 = 1.44, P = 0.230), but it was significantly associated with parental intention to vaccination (χ2 = 8.82, P = 0.003) in univariate analysis. A possible reason was that the measure in my questionnaire refers to perceived susceptibility in future, so this measure was not associated with past behaviors.

Perceived severity of influenza

Perceived severity of children's influenza infection was significantly associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children. A study conducted in the USA indicated that perceived severity of contracting influenza was significantly associated with acceptance of influenza vaccine.[26] This finding of this study was consistent with the previous study.[17] Furthermore, the association became insignificant after adjusting for other variables in the multivariate logistic regression model, indicating that perceived severity had an indirect effect on parental intention through social norms or emotional variables. A possible explanation was that the parents perceived higher severity of influenza infection for children would probably have more worry about the disease.[19]

Perceived benefit of influenza vaccination

Perceived benefit of influenza vaccination was parental assessment of the positive consequences of adopting influenza vaccination to their children. It was reported that perceived benefit of influenza vaccination to children was significantly associated with influenza vaccination on children.[21] Another web-based survey found that the parents with higher intention to vaccinate their children believed the benefits of influenza vaccination.[17] Another study based on HBM also found that perceived higher benefits of influenza vaccination were positively associated with vaccination uptake behavior.[27] Perceived benefit of influenza vaccine was significantly and positively associated with both children's vaccination uptake and parental intention to vaccinate their children. These findings were consistent with previous literature.[17] However after adjusting for social norms, emotional factors and perceived control in the third step, these associations became insignificant. A possible explanation might be that parents perceived more benefit of influenza vaccination would have more confidence to vaccinate their children and thereby perceived control could be a possible mediator for the relationship between perceived benefits of influenza vaccination and parental intention and children's influenza vaccination uptake. This explanation needs to be confirmed in future longitudinal studies.

Anticipated regret

Anticipated regret for inaction is a forecast feeling about future consequence due to failing to take the action. It has been used in an extended version of theory of planned behavior (TPB) to predict behavioral intentions.[10] A longitudinal study conducted in Hong Kong found that higher anticipated regret for the negative consequence due to not taking vaccination was associated with higher intention to accept the vaccine.[23] Bults et al.’ study found that 6% parents accepted the vaccination for their children due to feeling of future regret if missing the vaccination opportunity for their children.[28] However, on the basic of the modified HBM, parents who anticipated higher regret for the negative consequence due to vaccinating their children were less likely to vaccinate their children in the past. A possible explanation was omission bias. It suggested that parents usually anticipated higher regret related to the consequence of action than that from inaction. Ritov and Baron identified omission bias in parents who decide not to vaccinate their children because of potential death in 1990.[29] A study conducted by Asch et al. reported omission bias on parents who would not have their children vaccinate against pertussis tended to consider the harmfulness of vaccination.[30] Connolly and Reb revealed that subjects would like to make less risky choice, but they would rate inactive options better than active.[31]

Social norms

Social norms is an extension of subjective norm,[32] defined as perceived social pressure from not only significant others but also general others to perform a behavior. Social norms are important predictor of vaccination intention.[23] It was found that perceiving the social norms regarding influenza vaccination (the statement: Most of the parents you know take their children for influenza shot/most people important to you think you should give your child an influenza shot) were positively associated with influenza vaccination.[33] Allison et al. also found the consistent result that belief that immunization was a social norm could increase parental acceptance of influenza vaccination in children.[34] In the study, social norms were significantly and strongly associated with children's vaccination uptake and vaccination intention in my study. This finding was consistent with that in a previous study conducted in the USA.[35] Parents who were influenced more by their family members, friends and other parents who had positive attitude towards child influenza vaccination were more likely to vaccinate their children. However, in my study, social norms are not significantly associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children in the next 12 month (OR = 1.81, 95% CI: 0.90–3.66). One possible explanation is the relative small sample size in my study. It is very likely to result a significant OR if we increase the sample size from the perspective of 95% CI. Other reasons were that emotion could mediate the association between social norms and intention or social norm could affect behavior without through intention. However, the underlying reasons should be confirmed in further studies.

Emotion

Emotion is one of the most frequent incorporated variables in risk analysis. When humans facing risk or treat, feeling worry/anxiety or fear might influence human's decision-making process.[36,37] However, one limitation of HBM is failing to taking into account the emotional influences.[10] A research reported that “worry about influenza” was significantly associated with parental intention regarding children's influenza vaccination.[38] The study of Janks et al. reported that 11% participants worried that the illness may become more serious after their children catching influenza. In the present study, worried about children influenza infection had positive direct effect on parental intention to vaccinate their children in the fully adjusted model. This result is consistent with the previous study conducted in France.[38] Worry was also found to be associated with a number of preventive behaviors such as avoiding crowds during influenza pandemic and adults’ uptake of influenza vaccination.[39,40]

Perceived control

Perceived control was a variable derived from TPB.[10] It reflected the confidence of an individual to implement a behavior based on the evaluation of the internal and external control factors, such as skills, abilities, barriers and opportunity.[10] Perceived control was found to have a direct effect on intention and behavioral change.[10] My study finds that perceived control remained a significant predictor for children's vaccination uptake and parental intention to vaccinate children in the fully adjusted models, being consistent with the assumption in TPB.

Perceived children's health status

Parents who perceived their children's health to be good versus those who perceived their children's health to be excellent had higher intention to vaccinate their children. However, parents who perceived their children's health to be poor did not have higher intention than those who perceived their children's health to be excellent. A possible reason was that parents who perceived their children in poor health status were more likely to be afraid of the side effects of influenza vaccine and harmful consequences on their children.

Children's vaccination uptake rate

In our sample, vaccination uptake rate against seasonal influenza was around 47% among children aged between 6 months and 48 months within the preceding 12 months. This rate was higher than that reported in the studies conducted in Zhuhai city among children aged between 6 months and 59 months[41] and Chongqing among children aged between 6 months and 2 years.[18] However, since subjects were recruited by using convenient sampling, the rate of vaccination uptake in our sample would not be representative to the whole population of the target children in Guangzhou.

Limitations of the study

This is a cross-sectional study with convenient sampling. Causal associations cannot be inferred from the study. Small sample size was relative small, due to limited time and resources. The participants were sampled from a hospital rather than the whole community. Therefore, selection bias cannot be avoided. Besides, the subjects recruited in this study were almost those living nearby the hospital. These subjects may be convenient to obtain the health information materials and health service from the hospital. Third, the results may be suffered from recall bias because parents were asked to recall about their children's vaccination uptake within the preceding 12 months. Forth, 79.2% participants were female, however, We don’t know whether there would be difference on decision making regarding children's vaccination against seasonal influenza between fathers and mothers.

Overall, vaccination uptake among children aged between 6 months and 3 years was 47.7%, and parental intention to vaccinate their children was 62.4% in my study. The hierarchical logistic regression model based on a modified HBM found that child's past history of influenza vaccination, perceived that children's health status was good, worry and anxious about child influenza infection, perceived control were significantly associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children after adjusted other predictors, while children's age, parent's past history of influenza vaccination, social norms, perceived control were significantly associated with children's influenza vaccination uptake in the full model. Higher anticipated regret about the negative consequence was negatively associated with children's vaccination uptake. Omission bias could be a barrier for parents’ decision on children's influenza vaccination. This study indicated that factors of children's past history of influenza vaccination, parents’ worry and anxiety about child influenza infection, parents’ past history of influenza vaccination, social norms were important for motivating parents to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza. Therefore, policy-making should consider strategies as follow:

Improve parents’ confidence to access the seasonal influenza vaccine to promote parents’ intention to vaccinate their children against seasonal influenza

Providing information cues such as advice from other parents whose children have been vaccinated to increase adherence to positive social norms would be effective to encourage seasonal influenza vaccination uptake among children. For example, we can invite some parents who have had their children vaccinated and would like to encourage others to do the same as well to participate campaigns on influenza vaccination

Information communication should also target on reducing anticipated regret about the negative consequence of vaccinating children.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Shao Guo

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Van-Tam J, Sellwood C. Seasonal influenza: epidemiology, clinical features and surveillance. Introduction to pandemic influenza. 2009:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Influenza (Seasonal) 2009. [Last updated on 2009 Apr 01; Last cited on 2013 Aug 10]. Available from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of U.S.A. Flu Information for Parents with Young Children. 2013. [Last updated on 2013 Mar 06; Last cited on 2013 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/parents/index.htm .

- 4.Grijalva CG, Craig AS, Dupont WD, Bridges CB, Schrag SJ, Iwane MK, et al. Estimating influenza hospitalizations among children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:103–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.050308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Influenza Vaccine Use. 2013. [Last cited on 2013 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/use/en/

- 6.Basta NE, Chao DL, Halloran ME, Matrajt L, Longini IM., Jr Strategies for pandemic and seasonal influenza vaccination of schoolchildren in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:679–86. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong NS, Li Y, Yang Z, Wang C, Liu Y, Li X, et al. Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of influenza. J Thorac Dis. 2011;3:274–89. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2011.10.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Educ Behav. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Educ Behav. 1974;2:328–35. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogden J. England: McGraw-Hill International; 2012. Health psychology. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenstock IM. Why people use health services. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1966;44:94–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor SE. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 1999. Health psychology. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maiman LA, Becker MH. The health belief model: origins and correlates in psychological theory. Health Educ Behav. 1974;2:336–53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooley CH. New York: Schocken Books: Transaction Publishers; 1992. Human nature and the social order. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Velde FW, Van der Pligt J. AIDS-related health behavior: coping, protection motivation, and previous behavior. J Behav Med. 1991;14:429–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00845103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leventhal H, Nerenz D. The assessment of illness cognition. In: Karoly P, editor. Measurement strategies in health psychology. New York: Wiley; 1985. pp. 517–54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flood EM, Rousculp MD, Ryan KJ, Beusterien KM, Divino VM, Toback SL, et al. Parents’ decision-making regarding vaccinating their children against influenza: A web-based survey. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1448–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, He J. Status and influence factors of influenza vaccine coverage rate among preschool children in Yuzhong district of Chongqing (in Chinese) Chong Qing Med. 2011;40:2656–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janks M, Cooke S, Odedra A, Kang H, Bellman M, Jordan RE. Factors Affecting Acceptance and Intention to Receive Pandemic Influenza A H1N1 Vaccine among Primary School Children: a Cross-Sectional Study in Birmingham, UK. IInfluenza Res Treat 2012. 2012:182565. doi: 10.1155/2012/182565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuma J, Smith S, Kirk R, Hagmann C, Zemel P. Beliefs and attitudes of caregivers toward compliance with childhood immunisations in Cameroon. Public Health. 2002;116:55–61. doi: 10.1038/sj/ph/1900813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen MF, Wang RH, Schneider JK, Tsai CT, Jiang DD, Hung MN, et al. Using the Health Belief Model to understand caregiver factors influencing childhood influenza vaccinations. J Community Health Nurs. 2011;28:29–40. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2011.539087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banyard P. Hachette UK: 2002. Psychology in Practice: Health: Health. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao Q, Cowling BJ, Lam WW, Fielding R. Factors affecting intention to receive and self-reported receipt of 2009 pandemic (H1N1) vaccine in Hong Kong: a longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowalk MP, Zimmerman RK, Lin CJ, Ko FS, Raymund M, Hoberman A, et al. Parental perspectives on influenza immunization of children aged 6 to 23 months. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:210–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Painter JE, Sales JM, Pazol K, Wingood GM, Windle M, Orenstein WA, et al. Psychosocial correlates of intention to receive an influenza vaccination among rural adolescents. Health Educ Res. 2010;25:853–64. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JY, Cantrell CH. Health disparities and prevention: racial/ethnic barriers to flu vaccinations. J Community Health. 2007;32:5–20. doi: 10.1007/s10900-006-9031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahrabani S, Benzion U. How Experience Shapes Health Beliefs The Case of Influenza Vaccination. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39:612–9. doi: 10.1177/1090198111427411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bults M, Beaujean DJ, Richardus JH, van Steenbergen JE, Voeten HA. Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) vaccination in The Netherlands: parental reasoning underlying child vaccination choices. Vaccine. 2011;29:6226–35. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritov I, Baron J. Reluctance to vaccinate: Omission bias and ambiguity. J Behav Decis Mak. 1990;3:263–77. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asch DA, Baron J, Hershey JC, Kunreuther H, Meszaros J, Ritov I, et al. Omission bias and pertussis vaccination. Med Decis Mak. 1994;14:118–23. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9401400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connolly T, Reb J. Omission bias in vaccination decisions: Where's the “omission”? Where's the “bias”? Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2003;91:186–202. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.(Reading, Mass.); 1975. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daley MF, Crane LA, Chandramouli V, Beaty BL, Barrow J, Allred N, et al. Misperceptions about influenza vaccination among parents of healthy young children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2007;46:408–17. doi: 10.1177/0009922806298647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allison M, Reyes M, Young P, Calame L, Sheng X, Weng H, et al. Parental attitudes about influenza immunization and school-based immunization for school-aged children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:751–5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181d8562c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daley MF, Crane LA, Chandramouli V, Beaty BL, Barrow J, Allred N, et al. Influenza among healthy young children: changes in parental attitudes and predictors of immunization during the 2003 to 2004 influenza season. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e268–e77. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sjöberg L. Worry and risk perception. Risk analysis. 1998;18:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1998.tb00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baron J, Hershey JC, Kunreuther H. Determinants of priority for risk reduction: the role of worry. Risk Anal. 2000;20:413–28. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.204041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Setbon M, Raude J. Factors in vaccination intention against the pandemic influenza A/H1N1. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20:490–4. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao Q, Cowling B, Lam WT, Ng MW, Fielding R. Situational awareness and health protective responses to pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liao Q, Wong W, Fielding R. How anticipated worry and regret predict seasonal influenza vaccination uptake among Chinese adults? Vaccine. 2013;31:4084–90. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiao H, Xu Y, Lin B, Cai X, Qiu X, Huang J. The status quo of vaccination against the flu among 6-59-month children and analysis of the affecting factors (in Chinese) J Nursing (China) 2009;9:13–15. [Google Scholar]