Abstract

Rationale

Relative quantification of proteins via their enzymatically digested peptide products determines disease biomarker candidate lists in discovery studies. Isobaric label-based strategies using TMT and iTRAQ allow for up to 10 samples to be multiplexed in one experiment, but their expense limits their use. The demand for cost-effective tagging reagents capable of multiplexing many samples led us to develop an 8-plex version of our isobaric labeling reagent, DiLeu.

Methods

The original 4-plex DiLeu reagent was extended to an 8-plex set by coupling isotopic variants of dimethylated leucine to an alanine balance group designed to offset the increasing mass of the label’s reporter group. Tryptic peptides from a single protein digest, a protein mixture digest, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae lysate digest were labeled with 8-plex DiLeu and analyzed via nanoLC-MS2 on a Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Characteristics of 8-plex DiLeu-labeled peptides, including quantitative accuracy and fragmentation, were examined.

Results

An 8-plex set of DiLeu reagents with 1 Da-spaced reporters was synthesized at a yield of 36%. The average cost to label eight 100 μg peptide samples was calculated to be approximately $15. Normalized collision energy tests on the Q-Exactive revealed that a higher-energy collisional dissociation value of 27 generated the optimum number of high-quality spectral matches. Relative quantification of DiLeu-labeled peptides yielded normalized median ratios accurate to within 12% of their expected values.

Conclusions

Cost-effective 8-plex DiLeu reagents can be synthesized and applied to relative peptide and protein quantification. These labels increase the multiplexing capacity of our previous 4-plex implementation without requiring high-resolution instrumentation to resolve reporter ion signals.

Keywords: isobaric labels, 8-plex DiLeu, relative quantification, multiplexing

INTRODUCTION

Candidate biomarker discovery requires the relative quantification of large numbers of proteins in disease versus control biological states. The combination of stable-isotope labeling methods and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) has provided an avenue to determine key proteins that undergo up- or down-regulation in comparative studies of biological systems. Isotope labeling techniques incorporate heavy isotopes onto molecules in different samples metabolically or chemically. Samples are combined post-labeling, and relative abundances of differentially labeled molecules can be calculated after LC-MS analysis by comparing their extracted ion chromatogram peak areas or MS/MS peak intensities. An assortment of unique quantitative labeling techniques has been developed in recent years, but these methods can be broadly categorized as either mass difference or isobaric labeling.

Mass difference labeling adds discrete mass shifts to analyte molecules by introducing heavy isotopes for multiplexed quantification. Extracted ion chromatogram areas or intensities of precursor ions corresponding to the light- and heavy-labeled peptides are compared to quantify relative peptide abundance. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) adds isotopic versions of essential amino acids to cell culture media devoid of those amino acids, producing labeled proteins via metabolic pathways.[1–5] Chemical labeling, on the other hand, covalently bonds isotopic molecules to reactive moieties. Isotope-coded affinity tags (ICAT) [6–8] target sulfhydryl groups of reduced proteins, and formaldehyde dimethylation[9–12] and mass differential tags for relative and absolute quantification (mTRAQ) target primary amines of enzymatically produced peptides.[13–15] Mass difference approaches are accurate, but the increase in spectral complexity of MS1 scans limits proteome coverage and multiplexing capacity. For example, a single peptide labeled with a triplex mass difference reagent will be selected for MS2 fragmentation and acquisition three times, reducing the efficiency of data-dependent acquisitions and negatively impacting proteomic coverage.[16] Recent efforts have solved this problem for high-resolution (>100k) MS users through development of a class of SILAC[17–21] and mass difference reagents,[22–24] NeuCode, that spaces labeled peptides apart by mDa mass differences, ensuring selection of all labeled peptides in one scan for subsequent MS2 fragmentation. Unfortunately, this solution is viable only to labs with access to high-resolution mass spectrometers like Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) and Orbitrap instruments.

Isobaric labeling provides multiplexed relative quantification without increasing spectral complexity. These reagents add identical mass shifts to differentially labeled peptides but generate discrete reporter ions upon tandem-mass fragmentation whose intensities are proportional to the relative peptide abundances. This sophisticated design consists of a reporter group, a mass balance group, and a reactive group. By counteracting increasing numbers of isotopes into the reporter group with decreasing numbers of isotopes in the balance group, each unique tag in a multiplex set has the same nominal mass. Accordingly, each tag introduces an identical mass shift to labeled peptides but fragment into discrete reporter ions in the low-mass region that accompany b- and y-type peptide fragment ions upon MS2 analysis. The reporter ion intensities can then be compared and used to determine up- and down-regulated proteins in biomarker discovery experiments. The most commonly used isobaric labels in proteomics workflows are Thermo Scientific’s tandem mass tags (TMT)[25–28] and AB SCIEX’s isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ).[29–31] While the first-generation iterations of these reagents are still used, industrial and academic labs have invested considerable effort and resources to increase the number of channels provided by isobaric labels.

Investigators have increased the number of channels provided by isobaric labeling techniques by increasing the size of the mass balance group, combining mass difference and isobaric labeling, and adding mass defect-based isotopologues. The original 4-plex iTRAQ reagent was expanded to eight quantitative channels through the addition of a larger balance group to support greater numbers of isotopes in the reporter group.[32] However, derivatizing peptides with the bulky 8-plex iTRAQ reagents (Δm = 304.2 Da) may yield fewer peptide identifications when compared to smaller labels.[33] The coupling of mass difference and isobaric labeling methods, known as hyperplexing, was first demonstrated by tagging triplex SILAC-labeled peptides with 6-plex TMT to enable 18-plex quantification.[34] Medium and heavy versions of isobaric TMTs were then added to achieve 54-plex quantification, but the drastic elevation in sample complexity using this method limits its applicability to targeted protein assays.[35] Combined precursor isotopic labeling and isobaric tagging (cPILOT) is another hybrid technique that provides up to 16 channels for quantification by selective dimethylation of peptide N-termini at low pH prior to isobaric labeling of lysine side chains at high pH.[36,37] Thermo Scientific recently expanded the multiplexing capacity of their TMT reagents by exploiting mass defects to create a 10-plex set that is suitable for high-resolution MSn acquisition.[38,39] Four additional neutron-encoded reporter isotopologues that differ in mass by 6mDa from their original counterparts are made possible by differences in nuclear binding energies between light and heavy carbon and nitrogen isotopes. A resolving power of 30k (at 400 m/z) is necessary to observe these mass defect-based reporter ion signals in MSn scans, so their use is limited to researchers with access to high-end instrumentation.[39]

The high cost of commercial isobaric labels limits their practicality in biomarker discovery experiments. Researchers aiming to incorporate highly multiplexed isobaric labeling into their quantitative workflows are met with substantially higher prices. Price comparisons reveal that while a 6-plex TMT reagent set costs $500 per experiment (100 μg peptide per channel), a high-resolution 10-plex TMT reagent set costs $900. Similarly, 8-plex iTRAQ reagents are priced at $650, but 4-plex iTRAQ reagents can be applied for $275. Many research labs are unable to consider commercial isobaric labeling approaches for their quantitative experiments because of the steep financial barrier.

Our lab previously developed a 4-plex set of N,N-dimethyl leucine (DiLeu) isobaric labels as a cost-effective solution for quantitative proteomics.[40] The elegant structure of the DiLeu reagent requires only two or three steps to synthesize at high yield (~80%) using commercially available isotopic reagents, adds a modest amount of mass of 145.1 Da to the N-terminus and lysine side chains of labeled peptides, and fragments into four discrete reporter ions at m/z 115.1, 116.1, 117.1, and 118.1.[40] Protein sequence coverage and quantitative accuracy of DiLeu-labeled peptides were shown to be comparable in performance to iTRAQ-labeled peptides, and a following study suggested that DiLeu labeling enhances fragmentation efficiency of crustacean neuropeptides.[41] The high-performance of 4-plex DiLeu labeling is complemented by its low price of under $5 per experiment, representing a significant cost advantage over commercial isobaric labels. In efforts to also provide the greater throughput of the highly-multiplexed commercial offerings, we have continued development of the DiLeu reagent to increase the number of quantitative channels.

In this work, we introduce an 8-plex set of DiLeu isobaric labeling reagents that features alanine as a balance group to support a greater number of isotopes in the dimethylated leucine reporter group. In doing so, we have doubled the multiplexing capacity without yielding an increase in mass spectral complexity or requiring high-resolution MSn acquisition to resolve the additional reporter ion signals. The resulting 8-plex DiLeu label adds a mass of 220.2 Da to labeled peptides, which remains lighter than the either 8-plex iTRAQ (Δm = 304.2 Da) or 10-plex TMT (Δm = 229.2 Da). We investigate the quantitative performance of the 8-plex DiLeu reagent set by labeling a bovine serum albumin digest, a protein mixture digest, and a complex yeast lysate digest and analyzing key characteristics of DiLeu-labeled peptides like fragmentation efficiency, retention time shifts, quantitative accuracy, and dynamic range using a Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Isotopic reagents used in label synthesis including leucines (L-leucine and L-leucine-1-13C, 15N), alanine benzyl esters (L-alanine benzyl ester hydrocholoride and L-alanine-2,3,3,3-d4 benzyl ester hydrochloride), heavy formaldehydes (CD2O and 13CD2O), sodium cyanoborodeuteride (NaBD3CN), 18O water (H218O) and deuterium water (D2O) were purchased from ISOTEC Inc. (Miamisburg, OH). Sodium cyanoborohydride (NaBH3CN), formaldehyde (CH2O), hydrogen chloride gas (HCl), phosphoric acid (H3PO4), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), N-ethyl-N′-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), Palladium on activated charcoal (Pd/C), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), iodoacetamide (IAA), tris hydrochloride, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), reagent-grade formic acid (FA), triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB), anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM, CH2Cl2), bovine serum albumin (BSA), serotransferrin, alcohol dehydrogenase, α-2-HS-glycoprotein, lysozyme C, ovalbumin, β-lactoglobulin, and α-casein were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Trypsin/Lys C mix and Saccharomyces cerevisiae lysate were provided by Promega (Madison, WI). Urea, ammonium bicarbonate, ACS grade methanol (MeOH), DCM, and acetonitrile (ACN, C2H3N) were purchased along with Optima LC-MS grade ACN, water, and FA from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Hydroxylamine solution (50%) was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA).

8-plex DiLeu label synthesis

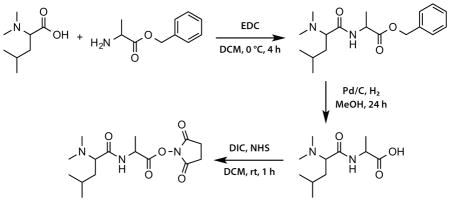

The general synthetic scheme to produce the 8-plex DiLeu reagent from N,N-dimethyl leucine and alanine benzyl ester is shown in Scheme 1. Additional synthetic details and specific isotopic reagents used in the synthesis of each of the eight labels can be found in the supporting information (Scheme S-1; Scheme S-2).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the 8-plex DiLeu reagent.

N,N-dimethyl leucine is coupled to alanine benzyl ester using EDC chemistry. Following hydrogenation of the benzyl ester, the carboxylic acid form is activated to the NHS ester form to produce the 8-plex DiLeu labeling reagent.

N,N-dimethyl leucine

L-leucine or L-leucine-1-13C,15N and a 2.5 molar excess of NaBH3CN or NaBD3CN was suspended in H2O or D2O and the reaction vessel was cooled in an ice-water bath. Formaldehyde (CH2O, 37% w/w) or isotopic formaldehyde (CD2O and 13CD2O, 20% w/w)(2.5 molar excess to leucine) was added dropwise, and the mixture was stirred for 30 min. The reaction progress was monitored by ninhydrin staining on a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate. The dimethyl leucine product was purified by flash column chromatography (DCM/MeOH) and dried in vacuo using a Büchi RE 111 Rotovapor (Switzerland).

Caution: Formaldehyde and sodium cyanoborohydride are toxic by inhalation, in contact with skin, or if swallowed and may cause cancer and heritable genetic damage. These chemicals and reactions must be handled in a fume hood.

18O Exchange of N,N-dimethyl leucine

The 115, 116, 119, and 120 labels require 18O exchange prior to formaldehyde dimethylation. L-leucine or L-leucine-1-13C,15N was dissolved in 1N H218O (pH 1) and stirred at 65 °C for 4 h. After HCl evaporation, traces of acid were removed with StratoSpheres PL-HCO3 MP resin (Agilent Technologies).

Alanine benzyl ester hydrochloride synthesis (AlaOBn HCl)

Alanine benzyl ester hydrochloride was synthesized as described previously.[42] L-alanine was added to a 1:10 v/v solution of phosphoric acid and benzyl alcohol. The mixture was stirred at 92°C for 8 h and then mixed with a 1:10 v/v solution of concentrated sulfuric acid in water. The mixture was treated with ether, and the aqueous phase was separated and adjusted to pH 10 with sodium bicarbonate. The solution was extracted with ether three times and the organic layer was dried with MgSO4. After filtration, the filtrate was bubbled with HCl(g) to precipitate the alanine benzyl ester hydrochloride product.

Dimethyl leucine coupling to alanine benzyl ester (DiLeuAlaOBn)

A 1:1 molar ratio of dimethyl leucine and L-alanine benzyl ester hydrochloride or L-alanine-2,3,3,3-d4 benzyl ester hydrochloride were mixed with a 1.2 molar excess of EDC and dissolved in DCM. The reaction vessel was cooled an ice-water bath and stirred for 4 h. After the reaction was complete, the product was separated from aqueous salts via liquid-liquid extraction (DCM/NaHSO3), and the organic layer was dried with MgSO4. The filtered DiLeuAlaOBn product was purified by flash column chromatography (DCM/MeOH) and dried in vacuo.

Palladium catalyzed hydrogenation (DiLeuAlaOH)

A slurry of Pd/C in MeOH was made by adding MeOH dropwise to Pd/C. The slurry was mixed with DiLeuAlaOBn, and the reaction chamber was sealed and evacuated of air. Hydrogen gas was supplied to the reaction vessel, and the mixture was stirred for 24 h. The slurry was filtered with a sintered glass Buchner funnel, and the DiLeuAlaOH product was dried in vacuo.

Caution: Addition of MeOH to Pd/C can cause sudden ignition. MeOH should always be slowly added dropwise to Pd/C in order to prevent a fire hazard.

Caution: Hydrogen gas is a flammable gas that burns with an invisible flame and can form explosive mixtures with air. Handle with caution.

Activation to NHS ester form (DiLeuAlaOSu)

Each 8-plex DiLeu label was dissolved in anhydrous DCM, combined with NHS and DIC at a 0.9x molar ratio, and vortexed at room temperature for 1 h. The resulting 8-plex DiLeu NHS esters were dried in vacuo, dissolved in IPA, and used immediately for peptide labeling to produce optimal results.

Protein digestion

Protein samples included the following: (a) BSA; (b) an equimolar mixture of BSA, serotransferrin, alcohol dehydrogenase, α-2-HS-glycoprotein, lysozyme C, ovalbumin, β-lactoglobulin, and α-casein; and (c) yeast lysate. Proteins were reduced, alkylated, and digested with either trypsin (BSA & protein mixture) or trypsin/Lys C mix (yeast lysate) according the manufacturers protocol (Promega, Madison, WI) and desalted using a SepPak C18 SPE cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA). Digested peptides were divided into eight equal aliquots (in triplicate), dried in vacuo, and dissolved in 60:40 ACN:H2O prior to labeling.

Peptide labeling

8-plex DiLeu labeling was performed in triplicate by adding label at a 20:1 label:peptide ratio by weight and vortexing for 3 h. The labeling reaction was quenched by addition of hydroxylamine to a concentration of 0.25% of the sample volume. Labeled peptide aliquots were combined in ratios of 1:1:1:1:1:1:1:1 and 10:1:2:5:2:10:5:1 (115 to 122), dried in vacuo, and dissolved in strong cation exchange (SCX) resuspension buffer. Residual 8-plex DiLeu byproducts were removed using SCX SpinTips according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Protea Biosciences, Morgantown, WV). Samples were dried in vacuo and desalted using C18 OMIX pipette tips (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

LC-MS2 and LC-tMS2 acquisition

Labeled peptides were dissolved in 0.1% FA and separated using a Waters nanoAcquity UPLC system (Milford, MA) before introduction into a Thermo Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (San Jose, CA). Mobile phase A was water with 0.1% FA, and mobile phase B was ACN with 0.1% FA. Samples were injected and loaded onto a column fabricated with an integrated emitter tip as previously described.[43] The 75 μm ID microcapillary column was packed with 15 cm of Bridged Ethylene Hybrid C18 particles (1.7 μm, 130 Å, Waters). Yeast peptides were loaded onto the column in 100% A and separation was performed using a gradient elution of 0–5% mobile phase B over 0.5 min and 5–30% over 120 minutes at a flow rate of 350 nL/min; a 70 minute gradient was used for the protein mixture experiments. Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) experiments were run in profile mode with full MS scans ranging from m/z 380–1500 at a resolving power of 70K. The automatic gain control (AGC) target was set to 1 × 106, and the maximum injection time (IT) was 100 ms. For the yeast lysate experiments, the top 15 precursor ions were selected for MS2 higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) fragmentation with an isolation width of m/z 2.0 and then placed on a dynamic exclusion list for 30 s; a top 10 method with a dynamic exclusion of 5 s was used for the protein mixture experiments. Tandem mass spectra were acquired in profile mode at a resolving power of 17.5K with an AGC target of 1 × 105, a maximum IT of 150 ms, a normalized collision energy (NCE) of 27, and a fixed lower mass limit of m/z 110.

For the targeted MS2 (t-MS2) experiments, separation of BSA peptides was performed using a gradient elution of 0–10% mobile phase B over 0.5 min and 10–30% over 40 min. Data was acquired in profile mode by selecting target peptide ions at an isolation width of m/z 2.0 for MS2. The t-MS2 spectra were acquired in profile mode at a resolving power of 17.5K with an AGC target of 1 × 105, a maximum IT of 150 ms, an NCE of 27, and a fixed lower mass limit of m/z 110.

Data analysis

Identification of labeled tryptic peptides was performed using Proteome Discoverer (version 1.4.0288, Thermo Scientific). Raw files were searched against databases consisting of the appropriate protein sequences (Uniprot) or the Saccharomyces cerevisiae complete database (Uniprot, September, 2013) using the Sequest HT algorithm. Peptides produced by digestion with trypsin with a maximum of two missed cleavages were matched using precursor and fragment mass tolerances of 50 ppm and 0.03 Da, respectively. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+57.0215 Da) and 8-plex DiLeu labeling of N-termini (+220.1920 Da) were selected as static modifications. Methionine oxidation (+15.9949 Da) and 8-plex DiLeu labeling of lysine residues (+220.1920 Da) were chosen as dynamic modifications. Peptide spectrum matches (PSMs) were verified based on q-values set to 1% false discovery rate (FDR) using Percolator.[44] Raw quantification values, representing reporter ion intensities from DiLeu-labeled peptides, were gathered from raw files using Proteome Discoverer using a reporter ion integration tolerance of 20 ppm for the most confident centroid. Only the PSMs that contained all eight reporter ion channels were considered. Raw reporter intensities were exported to Excel, where impurity/interference correction factors were applied using a previously described method[45] imported from PTC Mathcad 14 (Needham, MA). Generated equations are shown in Figure S-1 (Supporting Information).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

8-plex DiLeu reagent synthesis

The original implementation of DiLeu is limited by its compact structure to four nominal mass reporters.[40] While the reporter group allows many isotopic variations, the carbonyl balance group has only two atoms available for isotopic substitution, and only four isotopic variants (12C=16O, 12C=18O, 13C=16O, and 13C=18O) are possible to balance four reporters spaced by 1 Da. To overcome this barrier, we reasoned that a larger balance group could be coupled to the existing dimethyl leucine reporter group to increase the multiplexing capacity.

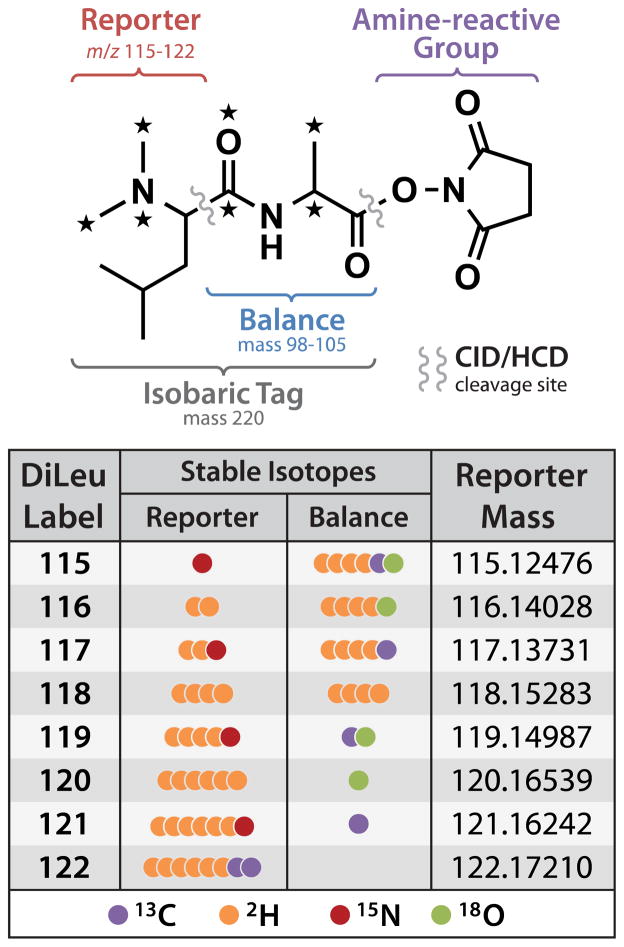

In designing the 8-plex DiLeu reagent, we chose to employ alanine as the balance group. The rationale is based on several factors: alanine can bear more isotopes to permit a greater number of isotopes to be incorporated into the reporter; isotopic alanines in various isotopic variations are commercially available; and methods of amino acid coupling are well established. Each tag consists of an isotopic variant of N,N-dimethyl leucine coupled to alanine or alanine-2,3,3,3-d4 and an NHS ester for selective labeling of peptide N-termini and lysine side chains. The NHS ester was chosen for the amine-reactive group over the triazine ester[40,41] used in the 4-plex DiLeu reagent because of its stability and its high reactivity with the DiLeuAlaOH molecule. Stable isotopes (13C, 15N, 2H, and 18O) are incorporated into the reporter and balance group to formulate a set of eight unique isobaric tags (Figure 1) that produce discrete reporter ions from m/z 115 to 122 (Figure S-2) upon MS2 fragmentation of labeled peptides. While the synthesis of the 8-plex DiLeu reagents requires two more steps than its predecessor (Scheme 1), it does not require advanced organic chemistry expertise. The incorporation of 18O was previously determined to be quantitative due to the great excess of H218O to leucine used in the reaction, and the dimethylation reaction gives yields of ~85%.[40] Linking dimethylated leucine to the alanine benzyl ester using EDC amino acid coupling chemistry produced yields of ~42% while hydrogenation of DiLeuAlaOBn to the carboxylic acid form was nearly quantitative. Isotopic DiLeuAlaOH appears to maintain stability over several months when stored in dry conditions, but the activated amine-reactive version should be used within one to two hours for highest quantitative accuracy. Isotopic leucines, alanine, alanine benzyl esters, and all other isotopic reagents involved in 8-plex DiLeu synthesis can be purchased commercially. Based on 100 mg bulk syntheses of each label from isotopic leucine and alanine starting materials, we calculate that the cost of labeling a 100 μg digest is approximately $15. This represents a three-fold increase in cost per labeling over the 4-plex set. Opting to reduce the number of synthetic steps by purchasing isotopic alanine benzyl ester commercially nearly doubles the cost, however. Several other straightforward synthetic routes to produce benzyl esters from carboxylic acids exist.[46–49]

Figure 1. Isobaric 8-plex DiLeu general structure.

The 8-plex DiLeu isobaric labeling reagent consists of an N,N-dimethyl leucine reporter group, an alanine balance group, and an amine-reactive NHS ester group. Stable isotopes (13C, 2H, and 15N) incorporated into the reporter group are balanced by stable isotopes (13C, 2H, 18O) in the balance group to create a set of eight isobaric tags that produce reporter ions at m/z 115–122 upon MSn fragmentation of labeled peptides.

In designing the 8-plex DiLeu reagent, we aimed to keep the tag’s modification mass small in order to avoid significant changes to fragmentation efficiency and peptide hydrophobicity. This choice was based on a previous report suggesting that a higher number of peptides were identified when labeled with lighter tags in comparison to peptides modified by bulkier labels.[33] Labeling of peptide N-termini and lysine side chains with 8-plex DiLeu adds a mass of 220.1290 Da per label. This modest mass addition compares favorably to 8-plex iTRAQ (Δm = 304.2 Da) and 10-plex TMT (Δm = 229.2 Da).

The 8-plex DiLeu set includes a 120 channel that produces a reporter ion at m/z 120.1654, which at low resolution can be interfered with in some MSn spectra by the phenylalanine immonium ion at m/z 120.0813. Baseline resolution of these two ions, which is required for accurate quantification of the 120 channel, can be achieved at a resolving power of approximately 3K. Because most modern mass analyzers commonly used today for isobaric labeling strategies are capable of this resolving power, we felt that the inclusion of the 120 channel was appropriate. However, the 8-plex DiLeu structure was designed to allow an isobaric 114 reagent to be synthesized in the case that the instrumentation cannot accommodate use of the 120 channel. Alternatively, the 114 reagent can complement the existing eight to enable 9-plex quantification. Synthesis of the 114 reagent requires an additional synthetic step and additional cost to produce the appropriate isotopic alanine linker (Scheme S-2, Supporting Information), so we opted to exclude it in this work due to the increased complexity.

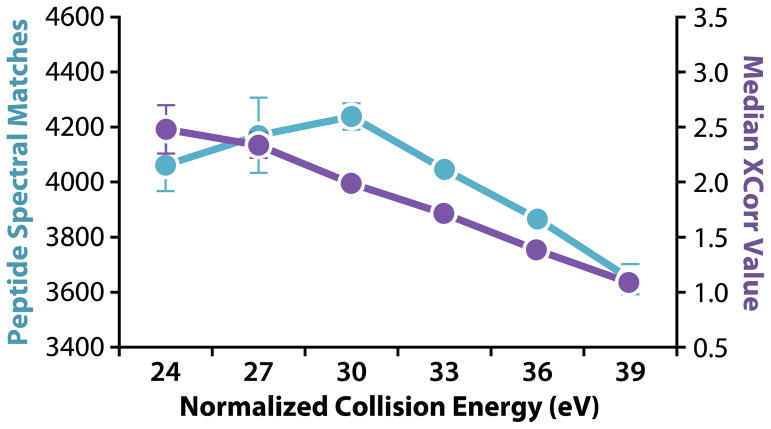

HCD NCE optimization for 8-plex DiLeu-labeled peptides

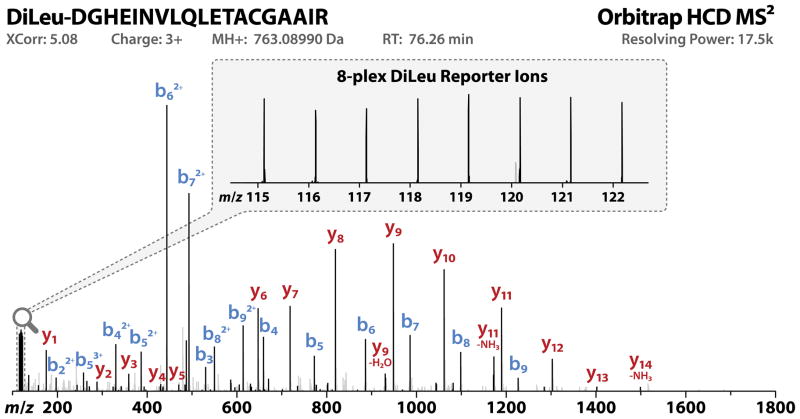

To assess the optimal normalized collision energy for 8-plex DiLeu-labeled peptides, we labeled an equimolar eight-protein mixture in 1:1 ratios across all channels and acquired LC-MS2 spectra on a Q-Exactive Orbitrap at HCD NCE values of 24, 27, 30, 33, 36, and 39. Peptides from the protein mixture were injected in duplicate for each NCE tested, and the resulting numbers of identified PSMs and median XCorr values were plotted as functions of NCE (Figure 2). High numbers of PSMs were identified with NCE values of 24–30, with the global maximum at 30. Peptide spectral match counts decreased at NCE values greater than 30. Quality of MS2 spectra for each run was determined by median XCorr values, which were highest at an NCE of 24. Median XCorr values decreased as NCE increased. Figure S-3 (Supporting Information) displays an example of the difference between MS2 spectra acquired at a fragmentation energy of 24 versus 39. At an NCE of 24, rich peptide fragmentation resulted in a high XCorr value and confident peptide identification. A collision energy of 39 yielded fewer b- and y-ions for peptide identification, and secondary fragmentation created overwhelming, intense reporter ion signals. We determined that an HCD NCE of 27 was optimal for 8-plex DiLeu labeled-peptides based on greater numbers of high-quality MS2 spectra, and we used this value for subsequent acquisitions of labeled yeast digest samples. Figure 3 shows an HCD MS2 fragmentation spectrum of an 8-plex DiLeu-labeled yeast peptide, DGHEINVLQLETACGAAIR, acquired using an NCE of 27. Notable features include abundant y- and adequate b-ion signals for confident peptide identification and eight discrete reporter ion channels (m/z 115–122) for relative quantification. Reporter ion ratios are close to unity but have not been corrected for isotopic impurities.

Figure 2. HCD normalized collision energy optimization.

An eight-protein tryptic digest sample labeled in triplicate with 8-plex DiLeu at 1:1 ratios across all channels was analyzed via LC-MS2 on the Q-Exactive Orbitrap using HCD NCE values of 24, 27, 30, 33, 36, and 39. The number of identified peptide spectral matches (blue) and median XCorr values (violet) were plotted as functions of NCE. An NCE of 27 was chosen for subsequent experiments based on the greater number of high-quality MS2 spectra.

Figure 3. 8-plex DiLeu labeled peptide MS2.

An MS2 spectrum of an 8-plex DiLeu labeled yeast tryptic peptide acquired on the Q-Exactive Orbitrap using HCD fragmentation (NCE 27) is shown. Reporter ions observed in the low mass region are suitable for 8-plex quantification and abundant peptide backbone ions allow confident peptide sequence identification. Peptide backbone fragment peaks contributing to the sequence identification of the peptide and the reporter ion peaks are black in color.

Reporter ion interference/impurities

Each 8-plex DiLeu reporter ion peak is accompanied by low-intensity isotopic peaks that are greater or lesser in mass by one neutron. These ‘isotopic impurities’ are a result of the 98–99% purity of isotopic substitution of the reagents used to synthesize the 8-plex DiLeu labels. Table S-1 (Supporting Information) shows the measured fractional intensities of the 8-plex DiLeu primary reporter ion peaks and isotopic peaks as percentages of their combined intensity. To obtain the greatest quantitative accuracy, correction factors for each channel can be calculated from these values. We recommend a previously described method that adds the intensities of the ±1 isotopic peaks and primary reporter ion peak of each channel while subtracting the intensities of any proximal interfering isotopic peaks from neighboring channels (Figure S-1, Supporting Information).[45] Low-resolution instruments cannot differentiate the isotopic peaks of neighboring channels from primary reporter ion signals, and isotopic interference correction must be applied to measured quantitative values. However, as MSn resolving power is increased, isotopic peaks begin to be resolved from the proximal primary reporter ion peaks, and the correction factor equations can be simplified. The minimum resolving power of 17.5K on the Q-Exactive Orbitrap is sufficient to partially resolve nearly all isotopic peaks from the proximal primary reporter ion peaks (Figure S-4, Supporting Information). Relative intensities of the primary reporter ion peaks and isotopic peaks should be determined for fresh batches of synthesized DiLeu by labeling a tryptic digest with each reagent and independently acquiring LC-MS2 data for each channel. Isotopic impurities can then be calculated as an average relative to reporter ion signal and applied as correction factors. While the correction factors work well for samples displaying ten-fold quantitative differences between adjacent channels, greater fold changes can result in the low abundance sample reporter ion peak being buried by the isotopic peak of the high concentration sample if the resolving power is not high enough to adequately separate the two peaks.[50] In this case, the 8-plex DiLeu reagents can provide greater dynamic range by offering 4-plex quantification in a 2 Da spaced configuration to avoid interference between channels.

Deuterium effects on peptide retention times

Incorporation of deuterium (2H) atoms onto peptide structures can alter their retention times during reversed-phase chromatography.[51] Published techniques to reduce this effect include grouping 2H around polar functional groups and minimizing the number of sites containing 2H.[52] The 8-plex DiLeu labels 116–122 incorporate one to three 2H atoms on the polar dimethylated amine. A previous study showed that placing 2H atoms in this position resulted in a minor 3% bias in ratios between H2 and 2H2-formaldehyde tagged peptides.[53] Our 4-plex DiLeu results have also shown that deuterium effects are minor when they are placed on the dimethylated amine.[40,41,54] The probability of 2H atoms interacting with a C18 column diminishes when they are positioned by hydrophilic groups with little to no affinity towards the stationary phase.[52]

The 8-plex DiLeu labels 115–118 contain four 2H atoms on the alanine balance group, and because these isotopes are not bonded close to a hydrophilic moiety, they may affect peptide retention times to some degree. We tested deuterium effects on 8-plex DiLeu-labeled BSA peptides by acquiring MS2 spectra for seven arbitrarily chosen peptides using a t-MS2 method. The t-MS2 technique records MS2 spectra only for peptides placed on an inclusion list, allowing us to compare extracted ion chromatograms for specific reporter ions across a peptide’s elution profile. Figure S-5 (Supporting Information) reveals an observable peptide retention time shift due to deuterium effects directly related to the 2H incorporation on the alanine linker of labels 115–118. Peptides labeled with the ‘deuterated’ channels 115–118 elute slightly before peptides labeled with the ‘non-deuterated’ channels 119–122. This effect appears to be peptide dependent. We propose normalizing relative quantitative ratios from channels 119–122 independently from channels 115–118 as a simple solution to compensate for the deuterium effect and obtain more accurate quantification.

To solve the problem of chromatographic retention shifting due to deuterium effects and allow accurate and precise quantification normalized to any channel, the 8-plex DiLeu labels 115–118 can be synthesized using non-deuterated alanine isotopologues such as alanine-13C3,15N or β-alanine-13C3,15N. The deuterated alanine balance group serves in this work to illustrate the proof-of-principle synthesis and application of the 8-plex reagents; future generations of these reagents will be synthesized with a non-deuterated balance group.

Quantification of yeast lysate digest

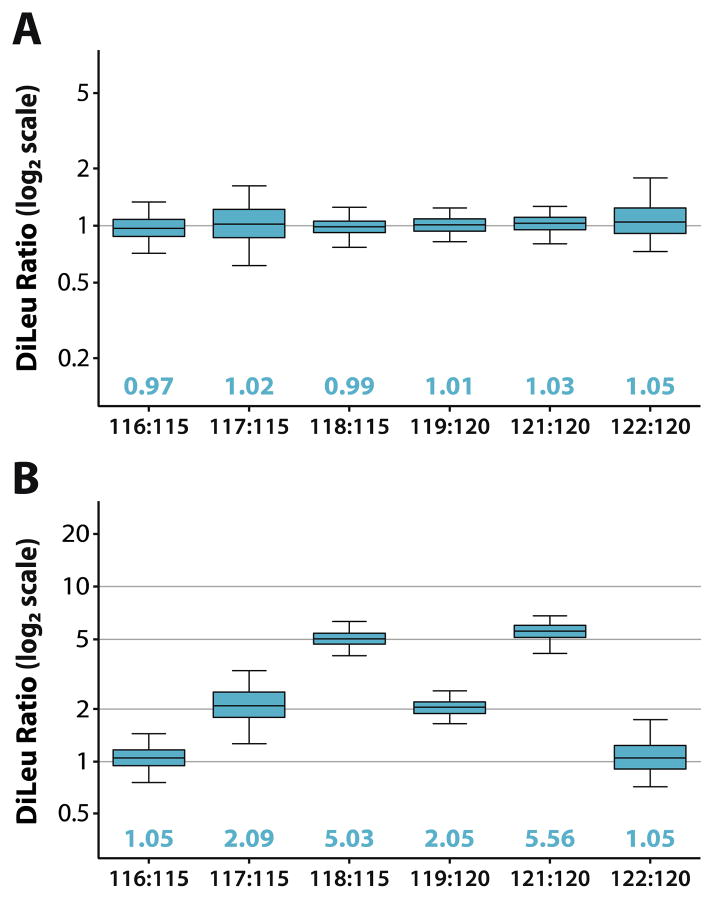

Quantitative performance was assessed using a complex yeast lysate digest sample. Peptides were labeled in triplicate with 8-plex DiLeu reagents and combined at molar ratios of 1:1:1:1:1:1:1:1 and 10:1:2:5:2:10:5:1 prior to LC-MS2 analysis. After correcting for pipetting error and DiLeu reagent purity, acquired data from the triplicate samples was combined in Proteome Discover to calculate quantitative ratios for 952 and 1049 identified protein groups from the 1:1 and 10:1 samples, respectively. Proteins were identified by 3989 and 4683 identified peptides across 18239 and 21692 PSMs for the respective 1:1 and 10:1 samples. Isotopic interference corrections were applied in Excel, and reporter ion ratios for all quantified proteins, normalized to channels 115 and 120, were plotted against each other (Figure 4). Median ratios across all eight channels measure within 5% and 12% of the expected values for the respective 1:1 and 10:1 samples with average coefficients of variation (CVs) of 22% and 26%. While quantification using 8-plex DiLeu was accurate, precision is lower than what we observe with 4-plex DiLeu. We believe that this may be due to impurities produced during the more complex multistep synthesis. A second database search was performed with N-terminus 8-plex DiLeu specified as a dynamic modification to estimate labeling efficiency. However, many peptides reported as being unlabeled actually contain strong reporter ion signals in the MS2 spectra. When precursor isolation interference is low enough to rule out co-isolation being responsible for the reporter ion signals, it can be assumed that the peptide is actually labeled. Based on close evaluation of the MS2 spectra of peptides reported as labeled and unlabeled, we estimate the labeling efficiency to be around 80%. While the labeling is not as efficient as 4-plex DiLeu, good quantitative performance is still observed for the peptides and proteins that were identified when 8-plex DiLeu was specified as a static N-term modification.

Figure 4. Quantitative performance.

A yeast lysate tryptic digest sample was labeled in triplicate with 8-plex DiLeu, combined in 1:1 ratios across all channels and in 10:1:2:5:2:10:5:1 ratios (115 to 122), and analyzed via LC-MS2 on the Q-Exactive Orbitrap. Measured quantitative ratios of identified peptides (box and whiskers) in relation to channels 115 and 120 are shown for (A) the 1:1 mixture and (B) the 10:1 mixture. Box plots demarcate the median (line), the 25th and 75th percentile (box), and the 5th and 95th percentile (whiskers).

To demonstrate the compensatory effect of calculating channels 119–122 independently, quantitative ratios of PSMs for channels 119, 121, and 122 were calculated in relation to either channel 115 or 120 and plotted against each other with fixed medians (Figure S-6). By normalizing the ratios of these channels to channel 120, the spread of the resulting values is significantly reduced and quantitative precision is improved.

Ratio compression, a common issue in isobaric label quantification studies caused by co-isolation of interfering near-isobaric species along with the target precursor during MS2 fragmentation,[50] was not observed in our benchmarking experiment since known amounts of labeled peptides originating from the same yeast digest were pooled. For unknown complex protein samples in which internal relative abundances of proteins vary between pooled samples, peptide co-isolation frequently results in significant compression of quantitative ratios. Several techniques have been published that aim to address this issue and restore quantitative accuracy of isobaric labeling strategies.[54–56]

CONCLUSIONS

We have designed, synthesized, and characterized the quantitative performance of novel isobaric 8-plex DiLeu labels. By coupling alanine to the original DiLeu reporter to support more isotopic variations, we have achieved a doubling of multiplexing capability without increasing MS1 spectral complexity or requiring the use of high-resolution MS2 to elucidate reporter ion signals. Additional synthetic steps result in a 36% yield for the 8-plex DiLeu reagents, and labeling experiments were calculated to cost approximately $15 for a 100 μg peptide sample. Characterization of the 8-plex DiLeu reagents revealed the following: 1) the optimal NCE was 27 for HCD-based fragmentation of 8-plex DiLeu-labeled peptides; 2) an MSn resolving power of 17.5K is sufficient to partially separate nearly all isotopic interferences from the primary reporter ion peaks; 3) the use of deuterium atoms in the alanine balance group can cause some peptides labeled with channels 115–118 to elute before those labeled with the 119–122 channels; 4) relative quantification of 8-plex DiLeu labeled-peptides is accurate when channels 119–122 are normalized independent of channels 115–118 to compensate for retention time shifts. Future iterations of the reagents will incorporate linkers in which heavy isotopes are limited to 13C, 15N, and 18O to avoid deuterium effects. We believe that the 8-plex DiLeu tagging strategy is a valuable addition to our existing custom-designed, cost-effective isobaric label options and should be of particular value to other research groups interested in adding highly multiplexed quantification to their proteomics workflows.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sergei Saveliev from Promega for providing the yeast lysate reference samples. The authors acknowledge support for this work by the National Institutes of Health grants 1R01DK071801 and 1R01NS071513, an Innovation & Economic Development Research program grant, and a Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation technology transfer grant. The Q-Exactive Orbitrap instrument was purchased through the support of an NIH shared instrument grant (NIH-NCRR S10RR029531). L.L. acknowledges an H. I. Romnes Faculty Research Fellowship.

References

- 1.Oda Y, Huang K, Cross FR, Cowburn D, Chait BT. Accurate quantitation of protein expression and site-specific phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu H, Pan S, Gu S, Bradbury EM, Chen X. Amino acid residue specific stable isotope labeling for quantitative proteomics. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2002;16:2115. doi: 10.1002/rcm.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, Steen H, Pandey A, Mann M. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:376. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan S, Gu S, Bradbury EM, Chen X. Single Peptide-Based Protein Identification in Human Proteome through MALDI-TOF MS Coupled with Amino Acids Coded Mass Tagging. Anal Chem. 2003;75:1316. doi: 10.1021/ac020482s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu S, Pan S, Bradbury EM, Chen X. Precise peptide sequencing and protein quantification in the human proteome through in vivo lysine-specific mass tagging. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:1. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00799-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gygi SP, Rist B, Gerber Sa, Turecek F, Gelb MH, Aebersold R. Quantitative analysis of complex protein mixtures using isotope-coded affinity tags. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:994. doi: 10.1038/13690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smolka MB, Zhou H, Purkayastha S, Aebersold R. Optimization of the isotope-coded affinity tag-labeling procedure for quantitative proteome analysis. Anal Biochem. 2001;297:25. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han DK, Eng J, Zhou H, Aebersold R. Quantitative profiling of differentiation-induced microsomal proteins using isotope-coded affinity tags and mass spectrometry. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:946. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji C, Guo N, Li L. Differential dimethyl labeling of N-termini of peptides after guanidination for proteome analysis. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:2099. doi: 10.1021/pr050215d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu Q, Li L. Fragmentation of Peptides with N-terminal Dimethylation and Imine/Methylol Adduction at the Tryptophan Side-Chain. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:859. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boersema PJ, Aye TT, Van Veen TAB, Heck AJR, Mohammed S. Triplex protein quantification based on stable isotope labeling by peptide dimethylation applied to cell and tissue lysates. Proteomics. 2008;8:4624. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y, Wang F, Liu Z, Qin H, Song C, Huang J, Bian Y, Wei X, Dong J, Zou H. Five-plex isotope dimethyl labeling for quantitative proteomics. Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50:1708. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47998f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeSouza LV, Taylor AM, Li W, Minkoff MS, Romaschin AD, Colgan TJ, Siu KWM. Multiple reaction monitoring of mTRAQ-labeled peptides enables absolute quantification of endogenous levels of a potential cancer marker in cancerous and normal endometrial tissues. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:3525. doi: 10.1021/pr800312m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon JY, Yeom J, Lee H, Kim K, Na S, Park K, Paek E, Lee C. High-throughput peptide quantification using mTRAQ reagent triplex. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(Suppl 1):S46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S1-S46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang CY, Kim K, Choi JY, Bahn YJ, Lee SM, Kim YK, Lee C, Kwon KS. Quantitative proteome analysis of age-related changes in mouse gastrocnemius muscle using mTRAQ. Proteomics. 2014;14:121. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mertins P, Udeshi ND, Clauser KR, Mani DR, Patel J, Ong S, Jaffe JD, Carr Sa. iTRAQ labeling is superior to mTRAQ for quantitative global proteomics and phosphoproteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:M111.014423. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.014423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hebert AS, Merrill AE, Bailey DJ, Still AJ, Westphall MS, Strieter ER, Pagliarini DJ, Coon JJ. Neutron-encoded mass signatures for multiplexed proteome quantification. Nat Methods. 2013;10:332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose CM, Merrill AE, Bailey DJ, Hebert AS, Westphall MS, Coon JJ. Neutron encoded labeling for peptide identification. Anal Chem. 2013;85:5129. doi: 10.1021/ac400476w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards AL, Vincent CE, Guthals A, Rose CM, Westphall MS, Bandeira N, Coon JJ. Neutron-encoded signatures enable product ion annotation from tandem mass spectra. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:3812. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.028951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merrill AE, Hebert AS, MacGilvray ME, Rose CM, Bailey DJ, Bradley JC, Wood WW, ElMasri M, Westphall MS, Gasch AP, Coon JJ. NeuCode labels for relative protein quantification. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014:1. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.040287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhoads TW, Rose CM, Bailey DJ, Riley NM, Molden RC, Nestler AJ, Merrill AE, Smith LM, Hebert AS, Westphall MS, Pagliarini DJ, Garcia BA, Coon JJ. Neutron-encoded mass signatures for quantitative top-down proteomics. Anal Chem. 2014;86:2314. doi: 10.1021/ac403579s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hebert AS, Merrill AE, Stefely Ja, Bailey DJ, Wenger CD, Westphall MS, Pagliarini DJ, Coon JJ. Amine-reactive neutron-encoded labels for highly plexed proteomic quantitation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:3360. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.032011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulbrich A, Merrill AE, Hebert AS, Westphall MS, Keller MP, Attie AD, Coon JJ. Neutron-encoded protein quantification by Peptide carbamylation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2014;25:6. doi: 10.1007/s13361-013-0765-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulbrich A, Bailey DJ, Westphall MS, Coon JJ. Organic Acid Quantitation by NeuCode Methylamidation. Anal Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1021/ac500270q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson A, Schäfer J, Kuhn K, Kienle S, Schwarz J, Schmidt G, Neumann T, Johnstone R, Mohammed aKa, Hamon C. Tandem mass tags: a novel quantification strategy for comparative analysis of complex protein mixtures by MS/MS. Anal Chem. 2003;75:1895. doi: 10.1021/ac0262560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dayon L, Hainard A, Licker V, Turck N, Kuhn K, Hochstrasser DF, Burkhard PR, Sanchez J. Relative quantification of proteins in human cerebrospinal fluids by MS/MS using 6-plex isobaric tags. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2921. doi: 10.1021/ac702422x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinclair J, Timms JF. Quantitative profiling of serum samples using TMT protein labelling, fractionation and LC-MS/MS. Methods. 2011;54:361. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy JP, Everley RA, Coloff JL, Gygi SP. Combining amine metabolomics and quantitative proteomics of cancer cells using derivatization with isobaric tags. Anal Chem. 2014;86:3585. doi: 10.1021/ac500153a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross PL, Huang YN, Marchese JN, Williamson B, Parker K, Hattan S, Khainovski N, Pillai S, Dey S, Daniels S, Purkayastha S, Juhasz P, Martin S, Bartlet-Jones M, et al. Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:1154. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeSouza L, Diehl G, Rodrigues MJ, Guo J, Romaschin AD, Colgan TJ, Siu KWM. Search for cancer markers from endometrial tissues using differentially labeled tags iTRAQ and cICAT with multidimensional liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:377. doi: 10.1021/pr049821j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo Y, Singleton PA, Rowshan A, Gucek M, Cole RN, Graham DRM, Van Eyk JE, Garcia JGN. Quantitative proteomics analysis of human endothelial cell membrane rafts: evidence of MARCKS and MRP regulation in the sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced barrier enhancement. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:689. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600398-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choe L, D’Ascenzo M, Relkin NR, Pappin D, Ross P, Williamson B, Guertin S, Pribil P, Lee KH. 8-plex quantitation of changes in cerebrospinal fluid protein expression in subjects undergoing intravenous immunoglobulin treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Proteomics. 2007;7:3651. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pichler P, Köcher T, Holzmann J, Mazanek M, Taus T, Ammerer G, Mechtler K. Peptide labeling with isobaric tags yields higher identification rates using iTRAQ 4-plex compared to TMT 6-plex and iTRAQ 8-plex on LTQ Orbitrap. Anal Chem. 2010;82:6549. doi: 10.1021/ac100890k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dephoure N, Gygi SP. Hyperplexing: a method for higher-order multiplexed quantitative proteomics provides a map of the dynamic response to rapamycin in yeast. Sci Signal. 2012;5:rs2. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Everley RA, Kunz RC, McAllister FE, Gygi SP. Increasing throughput in targeted proteomics assays: 54-plex quantitation in a single mass spectrometry run. Anal Chem. 2013;85:5340. doi: 10.1021/ac400845e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson RAS, Evans AR. Enhanced sample multiplexing for nitrotyrosine-modified proteins using combined precursor isotopic labeling and isobaric tagging. Anal Chem. 2012;84:4677. doi: 10.1021/ac202000v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans AR, Robinson RAS. Global combined precursor isotopic labeling and isobaric tagging (cPILOT) approach with selective MS(3) acquisition. Proteomics. 2013;13:3267. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201300198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Werner T, Becher I, Sweetman G, Doce C, Savitski MM, Bantscheff M. High-resolution enabled TMT 8-plexing. Anal Chem. 2012;84:7188. doi: 10.1021/ac301553x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McAlister GC, Huttlin EL, Haas W, Ting L, Jedrychowski MP, Rogers JC, Kuhn K, Pike I, Grothe RA, Blethrow JD, Gygi SP. Increasing the multiplexing capacity of TMTs using reporter ion isotopologues with isobaric masses. Anal Chem. 2012;84:7469. doi: 10.1021/ac301572t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiang F, Ye H, Chen R, Fu Q, Li L. N,N-dimethyl leucines as novel isobaric tandem mass tags for quantitative proteomics and peptidomics. Anal Chem. 2010;82:2817. doi: 10.1021/ac902778d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hui L, Xiang F, Zhang Y, Li L. Mass spectrometric elucidation of the neuropeptidome of a crustacean neuroendocrine organ. Peptides. 2012;36:230. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao M, Bi L, Wang W, Wang C, Baudy-Floc’h M, Ju J, Peng S. Synthesis and cytotoxic activities of beta-carboline amino acid ester conjugates. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:6998. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lietz CB, Yu Q, Li L. Large-Scale Collision Cross-Section Profiling on a Traveling Wave Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometer. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s13361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Käll L, Canterbury JD, Weston J, Noble WS, MacCoss MJ. Semi-supervised learning for peptide identification from shotgun proteomics datasets. Nat Methods. 2007;4:923. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shadforth IP, Dunkley TPJ, Lilley KS, Bessant C. i-Tracker: for quantitative proteomics using iTRAQ. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fauré-Tromeur M, Zard S. A practical synthesis of benzyl esters and related derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:7301. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tummatorn J, Albiniak PA, Dudley GB. Synthesis of benzyl esters using 2-benzyloxy-1-methylpyridinium triflate. J Org Chem. 2007;72:8962. doi: 10.1021/jo7018625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopez SS, Dudley GB. Convenient method for preparing benzyl ethers and esters using 2-benzyloxypyridine. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2008;4 doi: 10.3762/bjoc.4.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wuts PGM, Greene TW. Greene’s Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ow SY, Salim M, Noirel J, Evans C, Rehman I, Wright PC. iTRAQ underestimation in simple and complex mixtures: “the good, the bad and the ugly”. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:5347. doi: 10.1021/pr900634c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang R, Sioma CS, Wang S, Regnier FE. Fractionation of isotopically labeled peptides in quantitative proteomics. Anal Chem. 2001;73:5142. doi: 10.1021/ac010583a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang R, Sioma CS, Thompson Ra, Xiong L, Regnier FE. Controlling deuterium isotope effects in comparative proteomics. Anal Chem. 2002;74:3662. doi: 10.1021/ac025614w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boutilier JM, Warden H, Doucette Aa, Wentzell PD. Chromatographic behaviour of peptides following dimethylation with H2/D2-formaldehyde: implications for comparative proteomics. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2012;908:59. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sturm RM, Lietz CB, Li L. Improved isobaric tandem mass tag quantification by ion mobility mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2014;28:1051. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ting L, Rad R, Gygi SP, Haas W. MS3 eliminates ratio distortion in isobaric multiplexed quantitative proteomics. Nat Methods. 2011;8:937. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wenger CD, Lee MV, Hebert AS, McAlister GC, Phanstiel DH, Westphall MS, Coon JJ. Gas-phase purification enables accurate, multiplexed proteome quantification with isobaric tagging. Nat Methods. 2011;8:933. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.