Abstract

Background. It has been reported that pregnant women receiving protease inhibitor (PI)–based combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) have lower levels of progesterone, which put them at risk of adverse birth outcomes, such as low birth weight. We sought to understand the mechanisms involved in this decline in progesterone level.

Methods. We assessed plasma levels of progesterone, prolactin, and lipids and placental expression of genes involved in progesterone metabolism in 42 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected and 31 HIV-uninfected pregnant women. In vitro studies and a mouse pregnancy model were used to delineate the effect of HIV from that of PI-based cART on progesterone metabolism.

Results. HIV-infected pregnant women receiving PI-based cART showed a reduction in plasma progesterone levels (P = .026) and an elevation in placental expression of the progesterone inactivating enzyme 20-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20α-HSD; median, 2.5 arbitrary units [AU]; interquartile range [IQR], 1.00–4.10 AU), compared with controls (median, 0.89 AU; IQR, 0.66–1.26 AU; P = .002). Prolactin, a key regulator of 20α-HSD, was lower (P = .012) in HIV-infected pregnant women. We observed similar data in pregnant mice exposed to PI-based cART. In vitro inhibition of 20α-HSD activity in trophoblast cells reversed PI-based cART–induced decreases in progesterone levels.

Conclusions. Our data suggest that the decrease in progesterone levels observed in HIV-infected pregnant women exposed to PI-based cART is caused, at least in part, by an increase in placental expression of 20α-HSD, which may be due to lower prolactin levels observed in these women.

Keywords: pregnancy, HIV, antiretrovirals, protease inhibitors, progesterone, prolactin, 20-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, adverse birth outcomes, birth weight

The discovery of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has significantly reduced the morbidity and mortality associated with HIV infection [1, 2]. One of the greatest success stories of the HIV epidemic has been the ability to prevent vertical HIV transmission with cART. In 2012, 58% of HIV-infected pregnant women worldwide accessed ART [3].

The use of cART in pregnancy is undoubtedly beneficial; however, there are reported associations with adverse birth outcomes, including preterm delivery, small-for-gestational-age births, and low birth weight [4–9]. These outcomes increase the risk of infant morbidity and mortality, especially in low-resource settings. Given the expected increase in the number of pregnancies exposed to cART, it is important to understand the mechanisms that contribute to these adverse events, enabling selection of cART regimens that optimize pregnancy outcomes while minimizing risk of vertical transmission. Mechanistic studies may also elucidate interventions or adjunct maternal treatments that could improve both pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. The current World Health Organization guidelines recommend universal use of cART in pregnancy, initiated as early in pregnancy as possible and continued for the woman's lifetime [10]. Successful scale-up of this policy globally will dramatically increase the number of cART-exposed pregnancies.

Protease inhibitor (PI)–based cART is recommended during pregnancy in the United States and Canada and is used as second-line therapy in low-resource settings for pregnant women with virological failure during receipt of first-line therapeutics. Although controversial, several studies have suggested an association between PI-based cART and increased adverse pregnancy outcomes [9, 11–17]. The underlying mechanisms of PI-based cART–induced adverse birth outcomes have not been fully elucidated.

Progesterone is a sex steroid hormone essential for the maintenance of pregnancy, and in the general population, low levels of progesterone have been associated with preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and early pregnancy loss [18–20]. We have previously identified a decrease in circulating progesterone levels as a potential mechanism leading to fetal growth restriction in PI-based cART–exposed pregnancies [21]. Using a mouse pregnancy model, we demonstrated that PI-based cART administered throughout pregnancy resulted in lower progesterone levels that directly correlated with lower fetal weight. Administration of exogenous progesterone to these mice partially but significantly ameliorated the PI-based cART–induced fetal growth restriction. Further supportive data came from our observations of lower plasma levels of progesterone at gestational week 25–28 in HIV-infected women exposed to PI-based cART, compared with uninfected controls. Plasma progesterone levels in the HIV-infected women were significantly correlated to infant birth weight percentile [21].

During pregnancy, progesterone is synthesized from maternal cholesterol, initially in the ovary and by the eighth week of gestation in the placenta, and its metabolism relies on a number of enzymes, many belonging to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family [22]. Antiretrovirals, and PIs in particular, have been associated with dyslipidemia and altered expression and activity of several CYP enzymes (contributing to the drug interactions observed between PIs and hormonal contraceptives) [23]. The impact of PI-based cART on enzymes involved in progesterone metabolism during pregnancy is not known.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the mechanism by which PI-based cART decreases the concentration of progesterone during pregnancy, focusing primarily on enzymes involved in the synthesis and breakdown of progesterone. Using banked maternal samples and a mouse model of pregnancy, we demonstrate a possible mechanism through which PI-based cART use results in decreased progesterone levels. We demonstrate that PI-based cART is associated with reduced prolactin levels and increased placental expression of the prolactin-regulated, progesterone-inactivating enzyme 20-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20α-HSD).

METHODS

Reagents

Zidovudine (AZT), lamivudine (3TC), lopinavir (LPV), and ritonavir (RTV) were obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Reagent Program, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in 100 mM stock concentration, aliquoted, and stored at −20°C until use. Drugs were thawed at room temperature and dissolved in the cells' medium in 2 steps to avoid precipitation. The final concentration of DMSO was <0.1%. Combivir (ZDV/3TC, ViiV, Laval, Canada) and Kaletra (LPV/RTV, AbbVie, Saint-Laurent, Canada) were purchased as prescription drugs and used in the animal experiments.

Human Samples

The ethics boards of University Health Network, St. Michael's Hospital, Mount Sinai Hospital, and Women's College Hospital, Toronto, Canada, approved this study. Samples were obtained from women who consented to participate in a biobank program for the purpose of facilitating research involving HIV in pregnancy. The inclusion and exclusion criteria and detailed procedures have been described [21]. All HIV-infected women who were receiving a PI-based regimen and all available matched HIV-uninfected women recruited between September 2010 and December 2014 were included; there were 42 HIV-infected women and 31 HIV-uninfected women. All participants gave written informed consent. Plasma specimens were collected from heparinized late second trimester (gestational weeks 25–28) and third trimester (gestational weeks 34–37) blood samples (collected between 9:30 am and 12:30 pm) within 30 minutes of collection and were stored at −80°C. Sampling times were selected because they coincided with routine visits and because previous studies have shown that low progesterone levels in the second and third trimesters are associated with placental abnormalities, prematurity, fetal distress, and fetal growth restriction [18–20]. Placental tissue was collected from 4 sites (avoiding the umbilical and marginal regions) within 1 hour of delivery and preserved in Allprotect (Qiagen). For RNA extraction, tissue specimens from all 4 sites were pooled together.

In Vivo Mouse Model

All animal experiments were done in accordance with Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines and were approved by the University Health Network Animal Use Committee. Housing conditions, breeding, and drug treatment of mice have been described elsewhere [21]. Animals were administered ZDV/ 3TC (100/50 mg/kg/day), ZDV/3TC plus LPV/Ritonavir (RTV) (33/8·3 mg/kg/day), or water as a control starting at gestational day 1. At gestational day 15, heparinized blood specimens were collected by cardiac puncture, and placentas and ovaries were snap frozen. Parameters relating to birth outcomes were recorded as per our previous publication [21].

In Vitro Experiments

A total of 50 000 BeWo cells, a human trophoblast cell line (ATCC; catalog no. CCL-98), were seeded into 12-well plates in F-12K Medium (ATCC; catalog no. 30-2004), 24 hours prior to experimentation. Cells were incubated with antiretrovirals at 10X minimum effective concentration in a combination used in pregnancy (AZT/3TC/LPV/RTV) at 37°C in a 5% CO2, 95% air humid incubator for 24 hours, as previously described [21]. Cells incubated under hypoxic conditions (1% O2 and 99% N2) were used as a positive control. No toxicity (cell death) was observed under these conditions. For the 20α-HSD inhibition experiments, cells were incubated with antiretrovirals (as described above) for 24 hours, after which a fresh dose of antiretrovirals and increasing doses of the 20α-HSD inhibitor TBPP (3′,3′′,5′,5′′-Tetrabromophenolphthalein; Sigma Aldrich; catalog no. T1889) [24] were added for an additional 24 hours. In some experiments, BeWo cells were exposed to recombinant human prolactin (Sigma Aldrich; catalog no. L-4021) at increasing doses for 24 hours. No increase in cell death was observed at the end of the incubation period. Supernatants were collected, cleared by centrifugation, and stored at −80°C until testing. Cells were used for RNA extraction for expression analysis.

Biochemical Parameters

Human and mouse plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentrations were quantified using commercially available kits according to manufacturers' instructions (Sekisui Diagnostics; catalog no. SL234-60). Plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol concentration was calculated according the method of Friedewald et al [25]. Progesterone in cell supernatants (diluted 1:20) and human plasma (diluted 1:50) were assessed by a competitive enzyme immunoassay (EIA) according to the manufacturer's instructions (DRG International Germany; catalog no. EIA1561). Plasma prolactin (diluted 1:200) was assayed by EIA (R&D Systems; catalog no. DY682) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were assayed in triplicate.

RNA Extraction and Real-time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

RNA was extracted from BeWo cells, human placentas, and mouse placentas and ovaries using the Life Technologies Mirvana kit (catalog no. AM-1560) according to manufacturer's instructions. RNA quantity and purity were assessed using NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Scientific). Only samples with a 260 nm to 280 nm absorption ratio of ≥2.0 for RNA were used. RNA (100 ng/µL) was treated with DNAse I (Thermo Scientific; catalog no. EN-0525) and underwent reverse transcription to complementary DNA (cDNA), using the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad; catalog no. 170-8891). For mouse samples, cDNA was amplified in triplicate with SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche; catalog no. 04887352001) and forward and reverse primers (Supplementary Table 1A) in a LightCycler480 instrument (Roche). β-actin, 18S, and HPRT were used as housekeeping genes. Human cDNA was amplified in triplicate using SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad; catalog no. 172-526) and BioRad primer pairs (Supplementary Table 1B) in a LightCycler480 instrument (Roche). YWHAZ, CYC1, and TOP1 were assessed as housekeeping gene candidates [26]. Only YWHAZ showed general and even expression among samples, and it was selected as the reference gene. The relative quantification (ΔΔCt) method was used for gene-expression calculations [27].

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism (GraphPad, version 5). Groups were compared using the t test or Mann–Whitney U test, and analysis of variance or the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Dunn post hoc test, as appropriate. Correlation was assessed using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (r). In vitro experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least 3 times. Animal experiments were repeated 2–3 times. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant if the associated 2-tailed P value was <.05.

RESULTS

Lower Progesterone Levels in HIV-Infected Pregnant Women Exposed to PI-Based cART Are Not Due to Defects in Progesterone Synthesis

We have previously reported (using samples from a biobank of HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women) that HIV-infected pregnant women receiving PI-based cART had lower plasma progesterone levels at gestational weeks 25–28, compared with uninfected controls [21]. We used plasma and placenta samples from the same biobank to further investigate the mechanisms underlying these declines in progesterone levels. Demographic characteristics and birth outcomes of the participants are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

During pregnancy, progesterone is synthesized in the placenta from maternal cholesterol. This requires the transport of maternal LDL cholesterol first into the cell, via the LDL receptor [28], and then from the outer to the inner mitochondria membrane, via the metastatic lymph node 64 protein (MLN64) [29]. We observed no statistically significant difference in plasma total cholesterol levels and LDL cholesterol levels between HIV-infected and control women (Table 1). We also did not observe a significant difference in placental messenger RNA expression levels of LDL receptor and MLN64 between the groups (Table 2), although there was trend toward lower placental expression of LDL receptor in the HIV-infected group.

Table 1.

Plasma Total Cholesterol and Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) Cholesterol Concentrations in Pregnant Women, by Human Immunodeficiency Virus Status, and Pregnant Mice, by Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Received

| Variable | Women,a mmol/L, Median (IQR) |

Mice,b mmol/L, Median (IQR) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectedc | Uninfected | P Valued | PI-Based cART Exposure | Dual NRTI Exposure | Control | P Valuee | |

| Total cholesterol level | 3.30 (2.74–3.95) | 3.59 (2.74–4.64) | .34 | 3.52 (3.24–4.18) | 4.00 (3.82–4.23) | 3.67 (3.41–3.98) | .43 |

| LDL cholesterol level | 1.83 (1.33–2.21) | 2.29 (1.48–3.29) | .16 | 0.84 (0.67–1.02) | 0.75 (0.60–1.10) | 0.92 (0.84–1.05) | .53 |

Abbreviations: cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; IQR, interquartile range; LDL, low density lipoprotein; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

a Evaluated at gestational weeks 25–28. Data are for 20 women per group.

b Evaluated at gestational day 15. Data are for 7–8 mice per group.

c Exposed to PI-based cART.

d By the Mann–Whitney test.

e By the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Dunn post hoc test.

Table 2.

Real-time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Placental Genes Involved in Progesterone Metabolism in Pregnant Women, by Human Immunodeficiency Virus Status

| Gene | Infected,a AU, Median (IQR) | Uninfected, AU, Median (IQR) | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDL-r | 0.76 (0.58–1.12) | 0.97 (0.81–1.12) | .26 |

| MLN64 | 1.03 (0.82–1.24) | 0.89 (0.66–1.15) | .21 |

| CYP11A1 | 16.86 (3.86–209.5) | 22.50 (6.87–81.13) | .93 |

| 3β-HSD | 2.21 (1.70–2.88) | 2.71 (0.97–3.20) | .65 |

| 20α-HSD | 2.50 (1.00–4.10) | 0.89 (0.66–1.26) | .002 |

Data are for 20–27 women.

Abbreviations: 3β-HSD, 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/Δ-5-4 isomerase; 20α-HSD, 20-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. AU, arbitrary units; CYP11A1, cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme; IQR, interquartile range; LDL-r, low-density lipoprotein receptor; MLN64, metastatic lymph node 64 protein.

a Exposed to protease inhibitor–based combination antiretroviral therapy.

b By the Mann–Whitney test.

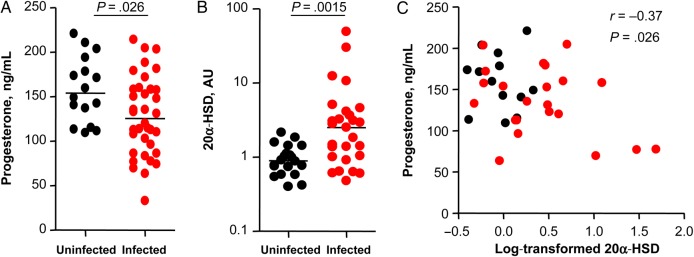

In the inner mitochondria membrane, cholesterol is converted to pregnenolone by the action of CYP11A1 and then to progesterone via 3-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) [30]. We observed no difference in the placental expression levels of CYP11A1 or 3β-HSD between the 2 groups (Table 2). We also did not observe a significant difference in the median levels of pregnenolone (measured at gestational weeks 34–37) between groups (12.1 ng/mL [interquartile range {IQR}, 8.6–18.2 ng/mL] among 34 HIV-infected women vs 15.6 ng/mL [IQR, 11.0–24.6 ng/mL] among 28 HIV-uninfected women; P = .13), although pregnenolone levels were slightly lower in the HIV-infected women. However, similar to our previous observations at gestational weeks 25–28 [21], we observed significantly lower plasma progesterone levels at gestational weeks 34–37 in HIV-infected pregnant women, compared with controls (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Plasma progesterone levels are decreased and placenta expression levels of 20-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20α-HSD) are increased in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected pregnant women exposed to protease inhibitor–based combination antiretroviral therapy, compared with those in HIV-uninfected pregnant women. A and B, Progesterone levels measured by an enzyme immunoassay in plasma collected during gestational weeks (GW) 34–37 (A) and placental expression levels of 20α-HSD assessed by real time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (B) from infected women and uninfected women. Data are shown as scatter plots with medians. Data are for 16 uninfected women and 36 infected women (A) or for 20 uninfected women and 27 infected women (B). Statistical comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney test. C, Plasma progesterone levels at GW 34–37 plotted against log-transformed levels of placental expression of 20α-HSD. Correlation was assessed by Spearman correlation (r). Abbreviation: AU, arbitrary units.

Placental Expression of 20α-HSD is Significantly Elevated in HIV-Infected Pregnant Women Exposed to PI-Based cART, Compared With HIV-Uninfected Controls

Since we did not observe any significant differences in the expression levels of enzymes upstream of progesterone synthesis or in the levels of progesterone precursors, we next investigated whether progesterone catabolism is altered in HIV-infected women exposed to PI-based cART. One of the major regulators of progesterone levels during pregnancy is 20α-HSD, an enzyme that converts progesterone to its inactive metabolite 20-α-dihydroprogesterone. Placental expression levels of 20α-HSD were 2.5-fold higher in the HIV-infected women as compared to controls (P = .002; Table 2 and Figure 1B). Additionally, expression levels of 20α-HSD inversely correlated with progesterone levels at gestational weeks 34–37 (Figure 1C), suggesting that high 20α-HSD levels may contribute to the lower progesterone levels seen in the HIV-infected women.

PI-Based cART Increases Placental Expression of 20α-HSD in a Mouse Pregnancy Model

To delineate the effect of HIV from that of PI-based cART on progesterone metabolism during pregnancy, we exposed healthy C57Bl/6 pregnant mice to either water or a dual nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) regimen (ZDV/3TC) as controls or to a PI-based cART regimen (ZDV/3TC/LPV/RTV). Fetal outcomes and levels of progesterone for these mice have been previously published [21] and showed lower progesterone levels in mice exposed to PI-based cART as compared to controls, which correlated with lower fetal weight.

In agreement with our findings in pregnant women, pregnant mice treated with PI-based cART, dual NRTI, or control had similar plasma concentrations of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol (Table 1) and placental expression of LDL receptor, MLN64, and CYP11A1 (Table 3). Further in agreement with our human data, we observed significantly higher expression levels of 20α-HSD in the placenta of mice exposed to PI-based cART, compared with those of mice exposed to either dual NRTIs or water (Table 3). Unlike in humans, the ovaries are the primary site of progesterone production in mouse pregnancy. We therefore also determined the ovarian expression of 20α-HSD and CYP11A1. Similar to our placenta findings, we observed no differences between groups in the expression levels of CYP11A1 but significantly higher levels of 20α-HSD in the ovaries of mice exposed to PI-based cART, compared to dual NRTI and water controls (Table 3). Thus, our mouse findings suggest that PI-based cART, in the absence of HIV infection, is associated with increased 20α-HSD expression.

Table 3.

Real-time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Placental Genes Involved in Progesterone Metabolism in Pregnant Mice, by Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Received

| Site, Gene | PI-Based cART Exposure, AU, Median (IQR) | Dual NRTI Exposure, AU, Median (IQR) | Control, AU, Median (IQR) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placenta | ||||

| LDL-r | 1.92 (1.45–2.62) | 2.35 (1.58–5.18) | 1.62 (0.97–3.87) | .11 |

| MLN64 | 1.68 (0.82–3.64) | 2.08 (1.64–3.73) | 1.70 (1.40–2.49) | .57 |

| CYP11A1 | 1.39 (0.65–1.62) | 1.64 (1.39–1.87) | 1.10 (0.74–1.47) | .15 |

| 20α-HSD | 5.33 (3.09–90.99)b | 1.60 (0.45–6.02) | 0.71 (0.44–2.80) | .028 |

| Ovary | ||||

| CYP11A1 | 1.12 (0.66–2.38) | 1.21 (1.17–1.62) | 1.04 (0.75–1.51) | .51 |

| 20α-HSD | 5.77 (4.18–79.14)b | 1.15 (0.46–4.79) | 0.93 (0.46–3.07) | .042 |

There were 8–12 mice per group.

Abbreviations: 20α-HSD, 20-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; AU, arbitrary units; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; CYP11A1, cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme; IQR, interquartile range; LDL-r, low-density lipoprotein receptor; MLN64, metastatic lymph node 64 protein; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

a By the Kruskal–Wallis test.

b P < .05 for the comparisons to controls and to dual NRTI recipients, by Dunn post hoc test.

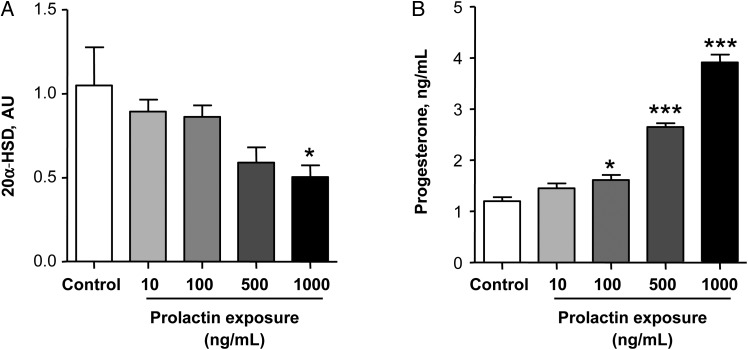

Inhibition of 20α-HSD Prevents PI-Based cART–Induced Decreases in Progesterone

To elucidate the importance of 20α-HSD in the regulation of progesterone levels by PI-based cART, we exposed BeWo cells to PI-based cART consisting of 2 NRTIs (AZT/3TC) and 2 PIs (LPV/RTV) in physiologically relevant concentrations. Similar to our previous observations [21], in a 24-hour period this drug combination significantly decreased progesterone levels in the supernatant by approximately 25%, compared with controls (Figure 2). Treating BeWo cells with the 20α-HSD inhibitor TBPP prevented the PI-based cART–induced decrease in progesterone levels in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2), implicating 20α-HSD in the PI-induced effects on progesterone.

Figure 2.

Progesterone deficiency in BeWo cells treated with protease inhibitor–based combination antiretroviral therapy (cART; zidovudine/lamivudine/lopinavir/ritonavir) is rescued by the 20-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20α-HSD) inhibitor TBPP. BeWo cells were treated with cART as described in Methods and with increasing doses of the 20α-HSD inhibitor TBPP for 24 hours. Progesterone levels were assessed in the supernatant by an enzyme immunoassay. Values are presented as mean ± SD for 4–6 independent experiments. Groups were compared using 1-way analysis of variance with the Dunn post hoc test. **P < .01 and ***P < .001.

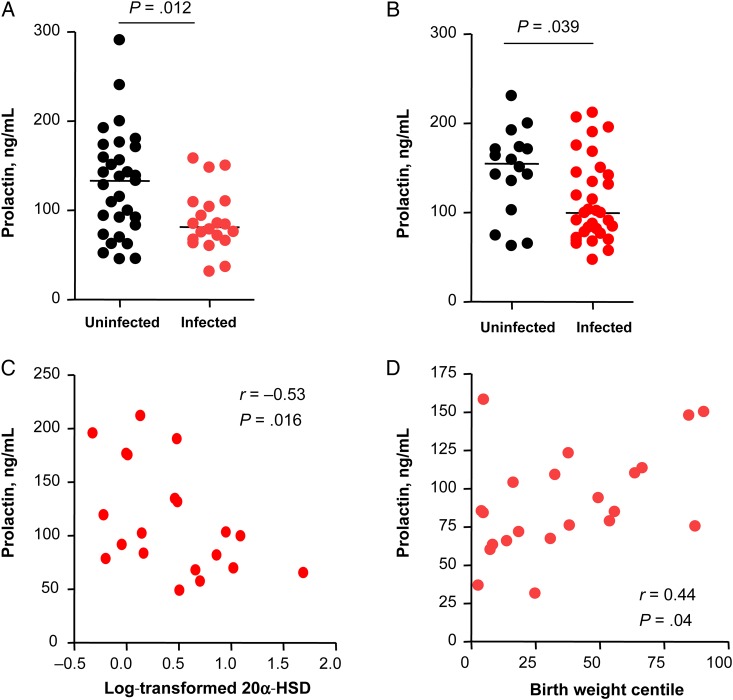

Prolactin Influences Progesterone Levels via Regulation of 20α-HSD Expression in Human Placental Cells

One of the potential regulators of 20α-HSD expression is prolactin [31]. To examine whether prolactin could influence progesterone levels via 20α-HSD, we exposed BeWo cells to increasing levels of prolactin and assessed expression of 20α-HSD and progesterone levels. Prolactin had a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on 20α-HSD expression in BeWO cells (Figure 3A). This effect was accompanied with a dose-dependent increase in progesterone levels (Figure 3B), suggesting that prolactin can regulate progesterone levels by controlling 20α-HSD expression.

Figure 3.

Prolactin exposure reduced the expression of 20-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20α-HSD) and increased the concentration of progesterone. A, Gene expression of 20α-HSD in BeWo cells treated with increasing concentrations of prolactin for 24 hours. B, Progesterone production in the supernatants of BeWo cells treated with increasing concentrations of prolactin for 24 hours. Data presented as means ± SD for 3–6 independent experiments. Groups were compared using 1-way analysis of variance with the Dunn post hoc test. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001, compared to control. Abbreviation: AU, arbitrary units.

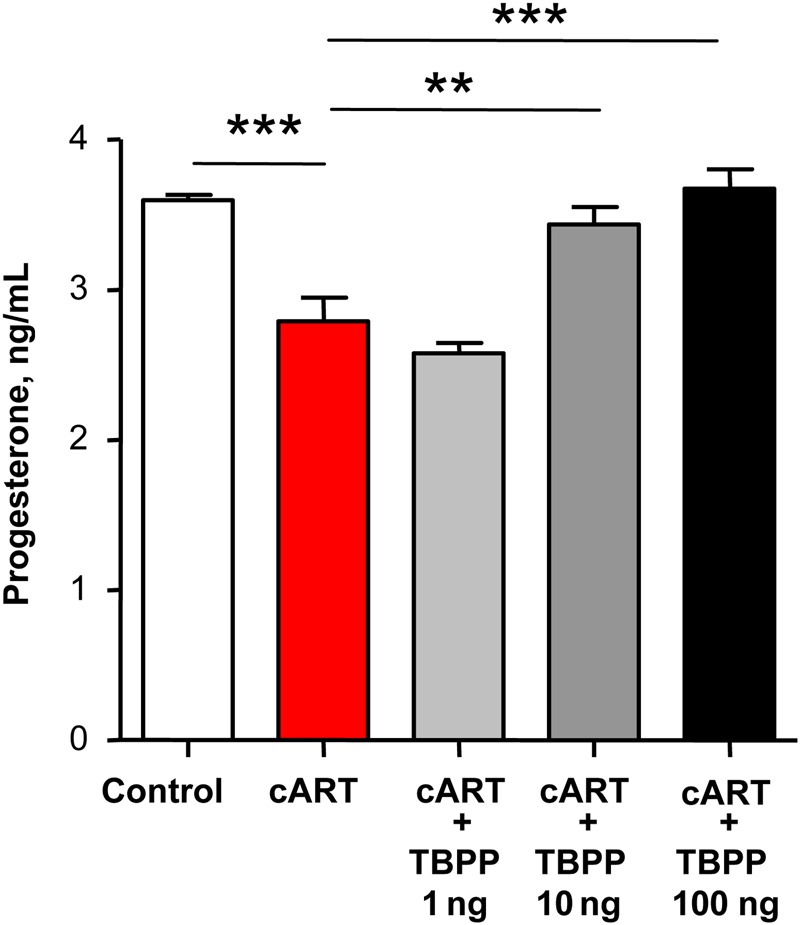

Prolactin Is Significantly Decreased in HIV-Infected Pregnant Women Exposed to PI-Based cART and Inversely Correlates With Placental 20α-HSD Expression

To determine whether the higher placental expression levels of 20α-HSD we observed in HIV-infected pregnant women exposed to PI-based cART could be related to changes in prolactin, we measured the levels of prolactin in plasma samples collected at gestational weeks 25–28 and 34–37. Prolactin levels were significant lower in the HIV-infected women as compared to those in controls at both time points (Figure 4A and 4B). Prolactin levels at gestational weeks 34–37 showed a significant inverse correlation with 20α-HSD expression in the placenta at delivery, suggesting that human placental 20α-HSD may be under prolactin regulation (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Prolactin levels are lower in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected pregnant women exposed to protease inhibitor–based combination antiretroviral therapy compared with those in HIV-uninfected pregnant women. A and B, Plasma prolactin concentration measured at gestational weeks (GW) 25–28 (A) and 34–37 (B) in infected women, compared with those in uninfected women. Data are shown as scatter plots with medians. Statistical comparisons were performed by the Mann–Whitney test. Data are for 31 uninfected women and 20 infected women (A) or 16 uninfected women and 32 infected women (B). C, Plasma prolactin levels at GW 34–37 among 20 infected women, plotted against the log-transformed placental levels of 20-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20α-HSD) expression. Correlation was assessed by Spearman correlation (r). D, Plasma prolactin levels at GW 25–28 among 20 infected women, plotted against birth weight centiles. Correlation was assessed by Spearman correlation (r).

We also observed a significant direct correlation between prolactin levels and birth weight centile (Figure 4D) in the HIV-infected group at gestational weeks 25–28. We have previously reported a significant correlation between progesterone levels and birth weight centile in the HIV-infected group at this time point [21]. We did not observe a significant correlation between prolactin or progesterone levels and birth weight centile at gestational weeks 34–37.

DISCUSSION

A number of studies have linked PI-based cART to adverse pregnancy outcomes, although the mechanisms remain unclear [6, 8, 12, 13, 15, 16, 32–34]. We have previously shown that exposure to PI-based cART during pregnancy is associated with lower progesterone plasma levels and that low progesterone levels contributed to fetal growth restriction [21]. We now demonstrate that PI-induced progesterone deficits maybe due to increased placental expression of the progesterone-metabolizing enzyme 20α-HSD, caused by low prolactin levels.

We observed higher placental expression levels of 20α-HSD in HIV-infected pregnant women exposed to PI-based cART as compared to uninfected pregnant women. We were able to induce increased expression of 20α-HSD by exposing pregnant mice to PI-based cART, thus linking higher 20α-HSD expression to PI exposure. Further, we were able to reverse PI-based cART–induced declines in progesterone levels by inhibiting 20α-HSD activity in vitro, implying a link between 20α-HSD activity and regulation of progesterone levels. Our novel finding that there is placental upregulation of 20α-HSD in the setting of PI-based cART indicates that PI-based cART is not influencing progesterone directly, but through a more complex pathway that inevitably involves increased degradation of progesterone by upregulated 20α-HSD. This pathway may include PI-based cART acting in some way to decrease prolactin levels.

20α-HSD catalyzes the reaction that converts metabolically active progesterone to an inactive product, 20α-dihydroprogesterone [35, 36]. Studies in primates have shown that the concentration of progesterone changes in response to the expression of 20α-HSD [37, 38] and that mice lacking 20α-HSD exhibit high circulating concentrations of progesterone and delayed delivery [35]. It is interesting to hypothesize that elevated levels of 20α-HSD may contribute to the higher rates of preterm delivery observed with PI use in pregnancy, but because of the low number of preterm deliveries in our cohort, we were unable to investigate this association.

Prolactin has been shown to regulate 20α-HSD at the gene expression level [39], and in situations of high demand of progesterone, such as pregnancy, prolactin downregulates 20α-HSD to allow progesterone levels to rise [40]. We observed significantly lower plasma prolactin levels in HIV-infected women exposed to PI-based cART as compared to controls at gestational weeks 25–28 and 34–37, as well as an inverse correlation between prolactin levels at gestational weeks 34–37 and placental 20α-HSD expression at delivery. Additional factors have been shown to regulate 20α-HSD expression in vitro and in animal models, including prostaglandin F2α [41], interleukin 1β [42], and miR-200a [43]. These merit further investigation in the context of HIV and pregnancy.

Although we found low prolactin levels in HIV-infected pregnant women receiving PI-based cART, some studies have reported hyperprolactinemia in HIV-infected nonpregnant individuals [44], and PIs have been shown to increase prolactin secretion from pituitary cells in vitro [45]. During pregnancy the major source of prolactin is the decidua, not the pituitary gland. Decidual and pituitary prolactin are differentially regulated [46], although the mechanisms that regulate decidual prolactin production have not been fully elucidated. It is therefore possible that PI-based cART exposure and/or HIV have different effects on decidual versus pituitary prolactin secretion. In addition to 20α-HSD expression, prolactin influences multiple processes during pregnancy [47], including implantation [48], angiogenesis [49], and estradiol receptor expression [50]. The consequences of lower prolactin levels in HIV-infected pregnant women exposed to PI-based cART and the underlying mechanisms that contribute to this remain to be determined.

In conclusion, our data suggest that the decrease in circulating progesterone concentration observed in HIV-infected pregnant women exposed to PI-based cART is caused by an increase in placental expression of 20α-HSD, an enzyme that converts progesterone to a metabolically inactive product. Our data also suggest a possible association between higher expression of 20α-HSD and lower prolactin levels in HIV-infected pregnant women exposed to PI-based cART. Further experimentation is required to establish a causal relationship between reduced plasma prolactin levels and increased placental levels of 20α-HSD. The majority of our HIV-infected women were receiving either a LPV-based or an atazanavir-based regimen. We plan to further investigate 20α-HSD and prolactin levels in the context of darunavir treatment, as our previous studies suggest that darunavir does not induce declines in the progesterone level in vitro [21]. Of note, we were able to observe a significant correlation between birth weight centile and prolactin levels at gestational weeks 25–28 but not at gestational weeks 34–37, mirroring our observations with progesterone [21]. Although these findings need to be confirmed in a larger cohort, our observations suggest that lower prolactin and lower progesterone levels in pregnancy influence fetal growth well before 34–37 weeks of gestational age. Further studies need to be done to identify whether a critical window exists during which fetal growth could be permanently impacted by PI-based cART.

Moreover, it is yet to be determined whether the adverse birth outcomes associated with decreased progesterone levels are specific to PI-based cART or whether similar effects could also be seen with non–PI-based regimens. Further studies could investigate progesterone and prolactin levels in HIV-infected pregnant women receiving non–PI-based regimens, particularly in Africa, where PI-based cART is not a first-line therapy option and where adverse birth outcomes can dramatically increase infant morbidity and mortality. It is important to note that many factors can contribute to adverse birth outcomes, of which progesterone is only one candidate.

In this study, we identify a mechanism that may underlie the reductions in progesterone levels we have previously observed with PI-exposure in pregnancy. These data enhance our understanding of antiretroviral safety in pregnancy and provide further evidence to support an intervention targeting this pathway as means of improving birth outcomes in cART-exposed pregnancies. Our group is currently pursuing a pilot randomized controlled trial of progesterone supplementation in HIV-infected pregnant women receiving PI-based therapy (clinical trials registration NCT02400021).

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://jid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the women who participated in the study; the study coordinators and labor and delivery staff at the recruiting sites; the National Institutes of Health (NIH) AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, for providing us with lopinavir, ritonavir, lamivudine, and zidovudine; and the Research Centre for Women's and Infant's Health BioBank, for aiding in the collection of some of the placenta samples used in this study.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant MOP130398, IHD123784, and the Emerging Team Grant in Maternal Health), the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (grant G605), and the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research (grant 024-016).

Potential conflicts of interest. S. L. W. reports receiving grants, personal fees, nonfinancial support, and other support from Viiv, Merck, Gilead, Jannsen, Bristol Meyers Squibb, and Abbvie outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 2008; 372:293–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahy M, Stover J, Stanecki K, Stoneburner R, Tassie JM. Estimating the impact of antiretroviral therapy: regional and global estimates of life-years gained among adults. Sex Transm Infect 2010; 86(suppl 2):ii67–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. World Health Organization global health report 2013. Geneva; World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JY, Ribaudo HJ, Souda S et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and adverse birth outcomes among HIV-infected women in Botswana. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1695–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagkeris E, Malyuta R, Volokha A et al. Pregnancy outcomes in HIV-positive women in Ukraine, 2000–12 (European Collaborative Study in EuroCoord): an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV 2015; 2:e385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kourtis AP, Schmid CH, Jamieson DJ, Lau J. Use of antiretroviral therapy in pregnant HIV-infected women and the risk of premature delivery: a meta-analysis. AIDS 2007; 21:607–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newell ML, Bunders MJ. Safety of antiretroviral drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding for mother and child. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2013; 8:504–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Short CE, Taylor GP. Antiretroviral therapy and preterm birth in HIV-infected women. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014; 12:293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watts DH, Mofenson LM. Antiretrovirals in pregnancy: a note of caution. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1639–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chougrani I, Luton D, Matheron S, Mandelbrot L, Azria E. Safety of protease inhibitors in HIV-infected pregnant women. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2013; 5:253–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powis KM, Kitch D, Ogwu A et al. Increased risk of preterm delivery among HIV-infected women randomized to protease versus nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HAART during pregnancy. J Infect Dis 2011; 204:506–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibiude J, Warszawski J, Tubiana R et al. Premature delivery in HIV-infected women starting protease inhibitor therapy during pregnancy: role of the ritonavir boost? Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1348–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorne C, Patel D, Newell ML. Increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in HIV-infected women treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy in Europe. AIDS 2004; 18:2337–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotter AM, Garcia AG, Duthely ML, Luke B, O'Sullivan MJ. Is antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, or stillbirth? J Infect Dis 2006; 193:1195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekouevi DK, Coffie PA, Becquet R et al. Antiretroviral therapy in pregnant women with advanced HIV disease and pregnancy outcomes in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS 2008; 22:1815–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ravizza M, Martinelli P, Bucceri A et al. Treatment with protease inhibitors and coinfection with hepatitis C virus are independent predictors of preterm delivery in HIV-infected pregnant women. J Infect Dis 2007; 195:913–4; author reply 6–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elson J, Salim R, Tailor A, Banerjee S, Zosmer N, Jurkovic D. Prediction of early pregnancy viability in the absence of an ultrasonically detectable embryo. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21:57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lachelin GC, McGarrigle HH, Seed PT, Briley A, Shennan AH, Poston L. Low saliva progesterone concentrations are associated with spontaneous early preterm labour (before 34 weeks of gestation) in women at increased risk of preterm delivery. BJOG 2009; 116:1515–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cousins LM, Hobel CJ, Chang RJ, Okada DM, Marshall JR. Serum progesterone and estradiol-17beta levels in premature and term labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1977; 127:612–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papp E, Mohammadi H, Loutfy MR et al. HIV protease inhibitor use during pregnancy is associated with decreased progesterone levels, suggesting a potential mechanism contributing to fetal growth restriction. J Infect Dis 2015; 211:10–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR et al. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev 1995; 9:2266–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tseng A, Hills-Nieminen C. Drug interactions between antiretrovirals and hormonal contraceptives. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2013; 9:559–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higaki Y, Usami N, Shintani S, Ishikura S, El-Kabbani O, Hara A. Selective and potent inhibitors of human 20alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (AKR1C1) that metabolizes neurosteroids derived from progesterone. Chem Biol Interact 2003; 143–144:503–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972; 18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drewlo S, Levytska K, Kingdom J. Revisiting the housekeeping genes of human placental development and insufficiency syndromes. Placenta 2012; 33:952–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001; 25:402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science 1986; 232:34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuckey RC, Bose HS, Czerwionka I, Miller WL. Molten globule structure and steroidogenic activity of N-218 MLN64 in human placental mitochondria. Endocrinology 2004; 145:1700–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller WL, Auchus RJ. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr Rev 2011; 32:81–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bao L, Tessier C, Prigent-Tessier A et al. Decidual prolactin silences the expression of genes detrimental to pregnancy. Endocrinology 2007; 148:2326–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dola CP, Khan R, DeNicola N et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy with protease inhibitors in HIV-infected pregnancy. J Perinat Med 2011; 40:51–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watts DH, Williams PL, Kacanek D et al. Combination antiretroviral use and preterm birth. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:612–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ades V, Mwesigwa J, Natureeba P et al. Neonatal mortality in HIV-exposed infants born to women receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in Rural Uganda. J Trop Pediatr 2013; 59:441–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishida M, Choi JH, Hirabayashi K et al. Reproductive phenotypes in mice with targeted disruption of the 20alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene. J Reprod Dev 2007; 53:499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuda J, Noda K, Shiota K, Takahashi M. Participation of ovarian 20 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in luteotrophic and luteolytic processes during rat pseudopregnancy. J Reprod Fertil 1990; 88:467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waddell BJ, Pepe GJ, Albrecht ED. Progesterone and 20 alpha-hydroxypregn-4-en-3-one (20 alpha-OHP) in the pregnant baboon: selective placental secretion of 20 alpha-OHP into the fetal compartment. Biol Reprod 1996; 55:854–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thau R, Lanman JT, Brinson A. Declining plasma progesterone concentration with advancing gestation in blood from umbilical and uterine veins and fetal heart in monkeys. Biol Reprod 1976; 14:507–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albarracin CT, Parmer TG, Duan WR, Nelson SE, Gibori G. Identification of a major prolactin-regulated protein as 20 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: coordinate regulation of its activity, protein content, and messenger ribonucleic acid expression. Endocrinology 1994; 134:2453–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhong L, Parmer TG, Robertson MC, Gibori G. Prolactin-mediated inhibition of 20alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene expression and the tyrosine kinase system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997; 235:587–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stocco CO, Zhong L, Sugimoto Y, Ichikawa A, Lau LF, Gibori G. Prostaglandin F2alpha-induced expression of 20alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase involves the transcription factor NUR77. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:37202–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberson AE, Hyatt K, Kenkel C, Hanson K, Myers DA. Interleukin 1beta regulates progesterone metabolism in human cervical fibroblasts. Reprod Sci 2012; 19:271–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams KC, Renthal NE, Condon JC, Gerard RD, Mendelson CR. MicroRNA-200a serves a key role in the decline of progesterone receptor function leading to term and preterm labor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:7529–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montero A, Fernandez MA, Cohen JE, Luraghi MR, Sen L. Prolactin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with HIV infection and AIDS. Neurol Res 1998; 20:2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orlando G, Brunetti L, Vacca M. Ritonavir and Saquinavir directly stimulate anterior pituitary prolactin secretion, in vitro. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2002; 15:65–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Handwerger S, Markoff E, Richards R. Regulation of the synthesis and release of decidual prolactin by placental and autocrine/paracrine factors. Placenta 1991; 12:121–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Devi YS, Halperin J. Reproductive actions of prolactin mediated through short and long receptor isoforms. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2014; 382:400–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horseman ND, Zhao W, Montecino-Rodriguez E et al. Defective mammopoiesis, but normal hematopoiesis, in mice with a targeted disruption of the prolactin gene. EMBO J 1997; 16:6926–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang X, Meyer K, Friedl A. STAT5 and prolactin participate in a positive autocrine feedback loop that promotes angiogenesis. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:21184–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frasor J, Gibori G. Prolactin regulation of estrogen receptor expression. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2003; 14:118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.