Abstract

Lentigo maligna (LM) and lentigo-maligna melanoma (LMM) are pigmented skin lesions that may exist on a continuous clinical and pathological spectrum of melanocytic skin cancer. LM is often described as a “benign” lesion and is accepted as a melanoma in situ; LM can undergo malignant transformation to particularly aggressive melanoma. LMM is an invasive melanoma that shares properties of LM, as well as exhibiting the metastatic potential of malignant melanoma. Unfortunately, LM/LMM diagnosis based on dermoscopy is rather ambiguous, and these lesions are often mistaken for junctional dysplastic nevi over sun-damaged skin, pigmented actinic keratosis, solar lentigo, or seborrheic keratosis. Diagnosis must be made on biopsy using distinct dermatopathologic features. These include a pagetoid appearance of melanocytes, melanocyte atypia, non-uniform pigmentation/distribution of melanocytes, and increased melanocyte density in a background of extensive photodamage. Advancements in immunohistochemical staining techniques, including soluble adenylyl cyclase (antibody R21), makes diagnosis easier and allows the definition of borders down to a single cell. After a pathologic diagnosis, there are a variety of treatment options, both surgical and non-surgical. Although surgical removal with a wide excision border is the preferred treatment due to decreased recurrence rates, experimental combination therapies are gaining popularity. However, no matter the treatment, LM/LMM carries a high recurrence rate, and patients must be monitored rigorously for recurrence as well as the appearance of additional skin lesions/cancers.

Keywords: Lentigo maligna, Lentigo-maligna melanoma, Pigmented actinic keratosis, Dermoscopy, Histopathology, Immunohistochemistry, Surgical excision, Non-surgical techniques

Introduction

Lentigo maligna (LM) is a pigmented skin lesion that is often mistaken for a “benign-type” lesion. However, to date, no longitudinal studies have proven this assumption. In fact, recent research is pointing to a continuous clinical and pathological spectrum of skin cancer spanning lentigo, LM, and lentigo-maligna melanoma (LMM) in the same fashion as benign nevus, melanoma in situ, and invasive melanoma. LM is currently considered to be “melanoma in situ”, with a 5–20% lifetime risk of progression to LMM [1], and represents 4–15% of all invasive melanomas [2], with properties of LM plus the metastatic potential of malignant melanoma [1, 3–5]. At this point, it is the dermatologist’s and dermatopathologist’s challenge to assess the risk of invasive potential of each pigmented lesion and to prevent further morbidity and mortality from melanoma transformation. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

LM and LMM

LM, formerly known as a Hutchinson melanotic freckle, is defined as “melanoma in situ” occurring at a site of chronic sun exposure. In 5–20% of patients, it will develop into an invasive melanoma, most often of the aggressive desmoplastic melanoma subtype [1]. This progression can take anywhere from less than 10 years to more than 50 years, and any time in between. Confusing as these statistics may seem, these data come from studies completed 30 years ago and have not yet been refuted [1, 3–5]. The probability that LM transforms into a melanoma increases if the LM exhibits variation in color, expanding surface area, increasing border irregularity, and/or development of elevated areas [1, 3–5].

LMM, on the other hand, is a subset of melanoma that accounts for 4–15% of melanoma diagnoses [1, 3–5]. Early studies suggested a lifetime risk of developing LMM from LM of 5% [6]; however, more recent work suggests that this number may be as high as 20% [7–9]. Ultraviolet radiation-induced mutation of the hair follicle has been suggested as the cause of LMM, producing a fairly aggressive and deep skin cancer [3, 4]. LMM is so named because it demonstrates features of LM in its in situ component, while also displaying features typical of invasive melanoma [1, 3–5]. Risk factors that predispose a patient to either LM or LMM include light skin that freckles, a history of non-melanoma skin cancer, and a history of sun damage/burn. However, the development of LM/LMM has no reported dose–effect relationship with respect to an individual’s cumulative sun damage or an association with the genetic propensity of an individual to form nevi [10, 11] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pigmented lesion of the cheek in an elderly man. Biopsy showed atypical intraepidermal melanocytic proliferation extending to the lateral margins. With anti-melan-A staining, a final diagnosis of melanoma in situ was made

LM and LMM have similar clinical presentation. The lesions are both found in chronically sun-exposed areas, often of the nose, cheeks, and ears (not often on the upper back, forearms, or legs). The peak incidence for both lesions is 65–80 years of age, but in recent years there has been increasing incidence in younger age groups (40–65 years), as witnessed in a cohort from northern California [1, 3, 12]. Characteristically, an LM/LMM will present as an atypical, non-scaly pigmented patch with ill-defined borders and variable size, shape, or shade (from tan to black to the rare amelanotic). These skin lesions grow radially and may grow/regress in a pattern that makes the LM/LMM appear to “move across” the skin [1, 3]. The skin surrounding the LM/LMM may also show signs of chronic solar damage [solar elastosis, solar lentigines, actinic keratosis (AK)]. If an LM develops dark pigmentation, sharp borders, or elevated areas, these changes may suggest a clinical progression to LMM [1, 3, 13].

Differential Diagnoses of LM/LMM

The differential diagnosis of LM/LMM includes myriad other pigmented skin lesions, including solar lentigo, seborrheic keratosis, lichen planus-like keratosis, junctional dysplastic nevus over sun damage, and pigmented AK [14–16]. However, there are distinct differences that can be used to distinguish between these differential diagnoses and the diagnosis of LM/LMM.

One of the most under-recognized differential diagnosis for LM/LMM is the pigmented AK [14]. Pigmented AKs are areas of skin that are damaged with ultraviolet radiation and are considered “pre-cancerous”. Without treatment, they may progress to either a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) within 2 years or a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) [17, 18]. Based on reporting as of 2012, it is thought that pigmented AKs arise as a collision between a non-pigmented AK and a separate but coexistent pigmented lesion such as a solar lentigo. Therefore, the pigmentation within a pigmented AK is not believed to be due to changes in the quality or quantity of melanocytes, as in a melanoma [19]. Histologically, a pigmented AK will show signs of apoptotic keratinocytes in the epidermis and upper dermis, hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis, melanophages in the papillary dermis, and increased melanin deposition [20, 21].

Dermoscopy of LM/LMM Versus Pigmented AK

Under the dermatoscope, a pigmented AK will have characteristics such as asymmetric pigmented follicular openings, hyperpigmentation of the follicle rim, light brown pseudo-networks, light rhomboidal structures, light streaks, and peripheral grey dots. Though these features are very similar to those found with LM/LMM dermoscopy, the lighter color pigment differentiates pigmented AK from LM/LMM [13].

There are three dermoscopic criteria that significantly differentiate a pigmented AK from a malignant LM/LMM: dark rhomboidal structures, dark streaks, and black blotches. Dark streaks and blotches are specific for LM/LMM at a rate of 97% and 100%, respectively [13].

LM skin lesions show characteristic black blotches, asymmetric hyperpigmented rims around follicular openings, dark rhomboidal structures (pigmented lines surrounding appendageal openings), asymmetric peripheral dark grey dots (indicative of superficial melanotic lesions, with a greater asymmetry proportional to greater malignancy), and annular-granular structures [13]. LMM skin lesions demonstrate features such as a target-like pattern (there is no definitive pathological correlate to date, but it is believed to be related to pilar infundibulum invasion), increased vascular density, dark streaks, and either an annular-granular or peppering pattern [22]. Four features in particular are hallmarks of LMM: asymmetric pigmented follicular openings, dark rhomboidal structures, slate-grey areas, and slate-grey dots/globules/pepper pattern. If all these structures are found in one lesion, they have 89% sensitivity and 96% specificity for a diagnosis of LMM [1, 13, 23, 24] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of dermoscopic and histological findings of pigmented AK, LM, and LMM [1, 10, 13, 16, 19–26]

| Pigmented AK | LM/LMM | LM | LMM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dermoscopy | |||

|

Precancerous Lighter color pigment (collision lesion) |

Dark streaks (97% specific) Dark blotches (100% specific) |

Melanoma “in situ” Asymmetric hyperpigmented rims around follicular openings Dark rhomboidal structures Asymmetric dark grey dots Annular-granular structures |

Melanoma Target-like pattern Increased vascular density Annular-granular or peppering pattern |

| Histology | |||

|

Apoptotic keratinocytes in epidermis and dermis Hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis Melanophages in papillary dermis Increased melanin deposition |

Atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia Extension of melanocytes down adnexal structures Melanocyte cellular atypia Non-uniform pigmentation and/or distribution of melanocytes Extensive photodamage: bridging/attenuation of rete ridges, epidermal atrophy, underlying elastosis, inflammation infiltrate in dermis “Skip lesions” |

||

Pigmented AKs are one of the most common differential diagnoses for LM/LMM. However there are differences on dermoscopy and histology that can help dermatologists and dermatopathologists distinguish between the different pigmented lesions. Most notably, asymmetric pigmented follicular openings, dark rhomboidal structures, slate-grey areas, and slate-grey dots/globules/pepper pattern all within one lesion are 89% sensitive and 96% specific for the diagnosis of LMM

AK actinic keratosis, LM lentigo maligna, LMM lentigo-maligna melanoma

Diagnosis of LM/LMM

The gold standard of LM/LMM diagnosis is the skin biopsy [1]; however, this standard is very limited in light of the high rate of diagnostic discordance among dermatopathologists [27]. Excisional biopsy is the optimal method, but may not be possible due to the size of the lesion or its location at a critical site such as the eyelid margin. An incisional biopsy site is chosen based on the most clinically significant areas by dermoscopic and clinical examination; unfortunately, due to site selection, there may be a risk of sampling error. In addition, it is also possible to perform a deep saucerization shave biopsy [1]. Both incisional and saucerization shave biopsies risk transection of the LM/LMM, therefore impacting histological diagnosis, although a recent study showed that melanoma transection does not necessarily impact overall disease-free survival or patient mortality [28]. On pathology, the diagnosis of LM/LMM is very subtle and easily missed; it is often mistaken for a junctional nevus overlying sun damage and therefore underdiagnosed [15].

Another instrument that can be used to determine the actual margins of the LM/LMM lesion is Wood’s lamp, which amplifies the difference in pigmentation between the LM/LMM and the surrounding normal tissue [16, 29]. Ultimately, however, it is often necessary to use clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathologic methods as complementary tools for a definitive diagnosis of LM/LMM.

Dermatopathologic features of both LM and LMM include atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia (a sign of chronic sun damage), extension of melanocytes down adnexal structures (LMM shows a characteristic pagetoid appearance), melanocyte cellular atypia (multinucleated with dendritic processes), non-uniform pigmentation and/or distribution of melanocytes, and increased melanocyte density [2, 30]. In addition, biopsies show extensive photodamage consisting of bridging/attenuation of rete ridges, epidermal atrophy, underlying elastosis, and inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis [10, 16, 26]. LM/LMM is notorious for skip areas on biopsy, leading to false-negative margins, and therefore it is often necessary to biopsy a larger area to determine where the true margins of the lesion lie [25]. Sometimes it may be useful to biopsy a “negative control” in an area of sun-damaged skin that appears normal; this will provide an individual’s background level of melanocytic hyperplasia/atypia that can serve as a reference [26]. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of LM/LMM is difficult, and there is not a high degree of concordance among dermatopathologists in interpreting excision margins [27].

To assist in the diagnosis of LM/LMM, a variety of immunostaining is available that can specifically mark melanocytes. HMB-45 (human melanoma black) is a monoclonal antibody that reacts against the antigen Pmel 17 in human melanocytic tumors; MART-1 (protein melan-A or melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) is a melanocyte surface antigen that is useful as a biomarker in melanocytic tumors (however, it is less specific, as it is found in benign nevi as well) [31, 32] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of markers that may be used for melanocytic immunostaining

| Marker | Identifies |

|---|---|

| Pmel 17 (antibody: HMB-45) [27, 28] | Melanocytic tumors |

| MART-1 (antibody: anti MART-1) [27, 28] | Melanocytic tumors (less specific; also found in benign nevi) |

| gp75 (antibody: Mel-5) [29] | Epidermal melanocytes in nevi and melanoma |

| S-100 (antibody: anti S-100) [30, 31] | Melanocytic tumors (also found in histiocytomas, schwannomas, neurofibromas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, paraganglioma stromal cells, clear cells sarcomas) |

| sAC (antibody: R21) [32, 33] | LM/LMM (combine with MART-1 to help define positive/negative margins) |

Pmel 17, MART-1, gp75 and S-100 are generally used for the identification of melanocytes in melanoma. sAC is a novel marker that is expressed pan-nuclearly in LM and LM, with detection sensitivity of 88%; using this technique, it is possible to detect the borders of LM/LMM down to a single cell

LM lentigo maligna, LMM lentigo-maligna melanoma, sAC soluble adenylyl cyclase

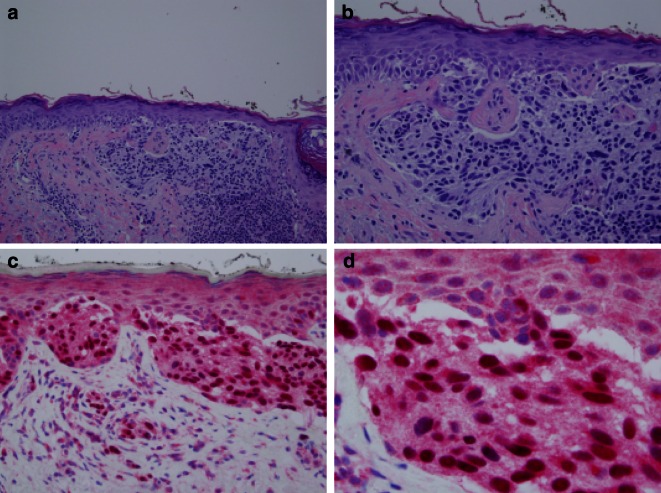

One of the most recent experimental advancements in histological techniques is immunostaining for soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC). sAC generates cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), a molecule needed for signaling and regulatory melanocyte function. R21 is a mouse monoclonal antibody that is directed against amino acids 203–213 of the human sAC protein. Research has shown that invasive LM/LMMs exhibit strong pan-nuclear R21 staining. Given this strong staining, studies have reported that sAC theoretically can help define the margins of excision down to the last cell showing nuclear expression of sAC (if margins are ill-defined, a combination of sAC/MART-1 staining can be used to determine positive versus negative margins) [33, 34]. A subsequent study determined that the sensitivity of R21 in detecting LM was 88% [34]. Though R21 immunostaining is very promising, R21 is not widely used due to limited availability [33, 34] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

sAC staining of a lentigo maligna melanoma from the face of a 64-year-old woman. a H&E staining at ×20; b H&E staining at ×40; c sAC staining at ×40; d sAC staining at ×100. sAC is a novel marker that is expressed in a pan-nuclear pattern in LM and LMM lesions. The detection with antibody R21 has an estimated sensitivity of 88 % and therefore can be used to determine the margins of the LM/LMM down to a single cell. Although this immunohistochemical stain is very promising, sAC is not yet widely used in dermatopathology labs due to its limited availability. H&E hematoxylin and eosin, LM lentigo maligna, LMM lentigo-maligna melanoma, sAC soluble adenylyl cyclase

Overview of Treating LM/LMM

For treatment of LM/LMM, there are both non-surgical and surgical methods. Non-surgical methods, depending on the type, have shown recurrence rates of 20–100% at 5 years; surgical methods have an average recurrence of 6.8% at 5 years [10]. Because of the high rates of recurrence in LM/LMM, the standard of care is surgical excision, except in cases such as elderly patients with multiple medical conditions who are inoperable or cases of large unresectable lesions. Surgical margins of 5–10 mm are recommended by multiple guidelines to ensure as complete of a resection as possible and to reduce the chance of recurrence. The most common surgical treatments include wide local excision, staged excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery [10, 35].

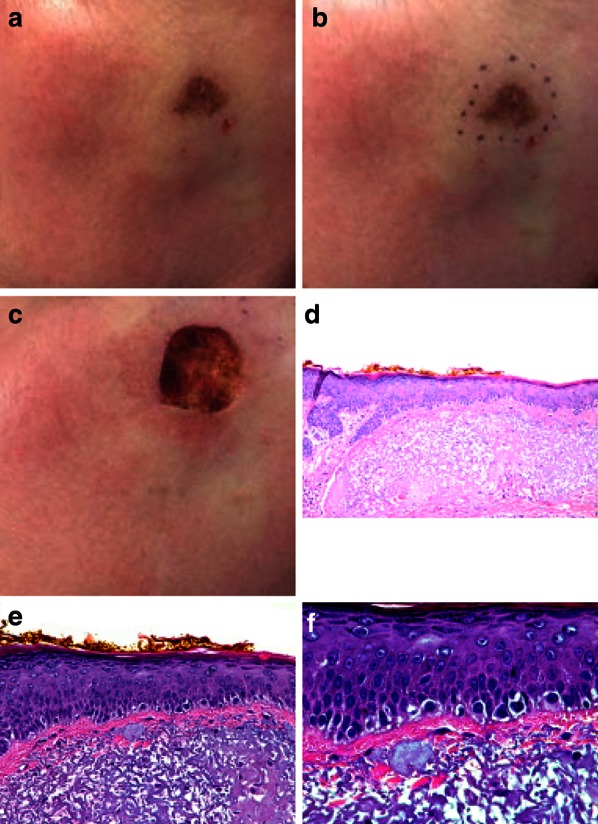

To date, there have been no formal clinical trials in which wide local excision has been evaluated with regard to optimal margins for LM/LMM, but a report from 2012 determined that 9-mm margins were adequate for complete clearance of the lesion in 99% of cases [36]. However, the recurrence rate with this technique is 6–9% over 3 to 3.5 years. Histological visualization may not be adequate in all cases, and removal of subclinical peripheral tissue may not be possible due to adjacent follicular involvement or the “field effect”, in which an extension of atypical melanocytes leads to a recurrence at the periphery of the treated area [10, 36, 37] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pigmented lesion of the cheek in a middle-aged woman. a Pigmented lesion before removal; b surgical borders as defined by Wood’s lamp; c surgical removal of the lesion; d H&E staining on low-power view (×10); e H&E staining on higher-power view (×20); f H&E staining on high-power view (×40). After removal of the lesion, dermatopathology revealed atypical intraepidermal melanocytic proliferation overlying dermal elastosis extending to all margins; the final diagnosis was melanoma in situ on sun-damaged skin. Even with borders defined by Wood’s lamp, the dermatopathologist deemed it necessary to go back and surgically remove more at all the margins. H&E hematoxylin and eosin

Mohs microscopic surgery uses frozen horizontal sections, allowing for faster processing of slides. In a comparison of frozen and permanent sections, only 5 % of margins that were negative in the frozen sections were actually positive by permanent section. Recurrence rates of 0–2% at 29–38 months have been reported with this method of surgical removal. Although frozen sections are more challenging to read on pathology because of the difficulty in interpreting melanocytic atypia, immunostaining with MART-1 or Mel-5 may help in the identification of melanocytes [10, 38, 39]. As it is almost impossible to determine melanocytic atypia on frozen sections, many believe this to be a serious limitation of the Mohs surgical technique for removal of LM/LMM.

Staged excision with rush permanent sections (a.k.a. “slow Mohs”) is thought to be the optimal treatment for LM/LMM, with recurrence of 0–5% at 23–57 months [10]. The most common surgery is geometric excision [40], although there are several variations of this surgical method, including square, perimeter, contoured, and spaghetti [41–44]. It is important to note that although LMM is considered a lower-risk melanoma, it still must be treated as a melanoma and excised with borders, consistent with standard treatment. However, the cons of this type of treatment include the time between each stage of excision and the inability to visualize all margins of the lesion, depending on the type of staged excision used [10]. Unfortunately, with all surgical treatments, the surgical wound can be much larger than the clinical lesion. Surgical wound healing may involve secondary intention, primary repair, skin graft, local flap, or distant flap [1, 10, 45]; the type of healing is based on the dermatologist’s best judgment.

Experimental non-surgical methods of treatment for LM/LMM all include the use of superficial destructive therapy. Though less invasive, non-surgical treatment methods are not preferred, due to the high rate of recurrence [1, 10]. Reasons for the high recurrence risk include insufficient topical application treating an inadequate surface area, topical treatment not reaching the skin depths needed to treat LM/LMM involving hair follicles, and the resistance of atypical melanocytes found in LM/LMM to destructive therapies. Unfortunately, after superficial destructive therapy, melanocytes may lose the ability to produce pigment, leading to hypopigmentation, which often delays the clinical diagnosis of recurrent LM/LMM [1, 10]. Non-surgical treatment options include cryotherapy/cryosurgery [46], radiotherapy [46–48], the use of Grenz rays [49], laser surgery including Q-switched Nd:YAG and CO2 (these treatments have the highest 5-year recurrence rate, at 43%) [1, 35, 50, 51], electrodesiccation with curettage [1, 35], photodynamic therapy [52], and 5% topical imiquimod (which may also be useful in treating amelanotic LM/LMM) [47, 53–56]. Radiotherapy is considered a superior non-invasive treatment method, as it may eradicate potentially invasive components of LM [46–48]. However, if this is not an option, combining non-surgical techniques with superior imaging (such as confocal microscopy) may also allow for appropriate assessment of response to therapy (Table 3).

Table 3.

| Characteristics | Recurrence rate at 5 years |

|---|---|

| Surgical treatment (gold standard of treatment) | |

| Wide local excision | |

| 9-mm margins clear 99% of cases | 6.8% |

| Recurrence rate 6–9% (36–42 months) | |

| Inadequate histological visualization (inadequate tissue removal, subclinical peripheral tissue not removed) | |

| Mohs microscopic surgery | |

| Misses 5% of positive margins | |

| Recurrence rate 0–2% (29–38 months) | |

| Immunostaining with MART-1 or Mel-5 | |

| Slow Mohs | |

| Considered the most best treatment | |

| Variations (geometric square, perimeter, contoured, spaghetti) | |

| Recurrence rate 0–5% (23–57 months) | |

| Not all margins of lesions may be visualized (technique-dependent) | |

| Non-surgical treatment (superficial destructive therapies) | |

| Cryotherapy, cryosurgery, radiotherapy, Grenz ray, laser surgery (switched Nd:YAG, CO2), electrodesiccation with curettage, PDT, 5% topical imiquimod | |

| Less invasive | 20–100% (dependent on treatment) |

| High rate of recurrence (treatment of inadequate surface area, treatment not reaching skin depth needed for LM/LMM invading hair follicles, atypical melanocytes resistant to destructive therapies) | |

| Laser therapy carries the highest risk of recurrence at 5 years | |

| Hypopigmentation after therapy leads to late diagnosis of recurrence (treat recurrence with imiquimod) | |

Treating LM/LMM is complicated, and dermatologists may choose to use either a surgical or experimental non-surgical method. Surgical treatment is considered the gold standard, due to the lower 5-year recurrence rate; staged excision with rush permanent sections (“slow Mohs”) is considered the ideal choice. Non-surgical treatment consists of various superficial destructive techniques, either singly or, more recently, in combination. However, non-surgical treatment carries a much higher risk of 5-year recurrence, and recurrence is harder to detect due to hypopigmentation of atypical melanocytes. Topical imiquimod may be used as neoadjuvant therapy before surgical staged excision, thus reducing the defect size post-surgery; this application of imiquimod does not carry the same recurrence risk as topical imiquimod used alone

LM lentigo maligna, LMM lentigo-maligna melanoma, PDT photodynamic therapy

In the follow-up of LM/LMM treatment, it is important to be aware of the field effect with extension of atypical melanocytes at the periphery of the treated area, which may occur after many years of remission [37]. The National Cancer Institute suggests follow-up every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years after treatment and annually thereafter [57].

Conclusions

LM is a pigmented lesion that can undergo malignant transformation from low-grade to particularly aggressive forms of melanoma. Perhaps similar to the spectrum of malignancy from AK to SCC [58], LM and LMM lie on their own dermatologic spectrum from melanoma in situ to malignant melanoma.

Due to ambiguous dermoscopy, LM/LMM are often mistaken for junctional dysplastic nevi over sun-damaged skin, pigmented AK, solar lentigo, or seborrheic keratosis, and therefore diagnosis must be made histologically. The gold standard of LM/LMM diagnosis is skin biopsy, allowing visualization of dermatopathologic features consistent with LM/LMM. These include a pagetoid appearance of melanocytes, melanocyte atypia, and non-uniform pigmentation and distribution of melanocytes, all on a background of extensive photodamage. Though traditional melanocyte stains such as Pmel 17, MART-1, and S-100, are often used for immunohistochemical analysis of LM/LMM, new antibodies are becoming available that may aid in the diagnosis of LM/LMM. The emergence of new immunostaining techniques such as sAC/R21 staining have made it easier to determine the true margins of the LM/LMM lesions.

Surgical removal of LM/LMM is the preferred treatment option due to the lower 5-year recurrence rates. Recently, experimental combination therapies such as excision and topical imiquimod [59, 60], laser therapy and topical imiquimod [61], or cryosurgery and topical imiquimod [62] have emerged. Unfortunately, even after treatment, LM/LMM still carries a high risk of recurrence, and therefore patients must be monitored rigorously afterwards. In addition, given the high degree of sun damage in patients with LM/LMM, screening for additional skin lesions/cancers should be completed by a knowledgeable dermatologist on a regular basis.

Acknowledgments

No funding or sponsorship was received for publication of this article. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. We would like to thank Dr. Cynthia Magro from Cornell University for providing the images used for Fig. 2 in this article. We would also like to thank Dr. Robert G. Phelps and the dermatopathology lab at Mount Sinai Hospital for their help in obtaining the slides used for Fig. 3.

Disclosures

Margit L.W. Juhász and Ellen S. Marmur have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

References

- 1.McKenna JK, Florell SR, Goldman GD, Bowen GM. Lentigo maligna/lentigo maligna melanoma: current state of diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Surg Off Pub Am Soc Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(4):493–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowen AR, Thacker BN, Goldgar DE, Bowen GM. Immunohistochemical staining with Melan-A of uninvolved sun-damaged skin shows features characteristic of lentigo maligna. Dermatol Surg Off Pub Am Soc Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(5):657–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.01946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark WH, Jr, Mihm MC., Jr Lentigo maligna and lentigo-maligna melanoma. Am J Pathol. 1969;55(1):39–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson R, Williamson GS, Beattie WG. Lentigo maligna and malignant melanoma. Can Med Assoc J. 1966;95(17):846–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zalaudek I, Marghoob AA, Scope A, Leinweber B, Ferrara G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, et al. Three roots of melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(10):1375–1379. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.10.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstock MA, Sober AJ. The risk of progression of lentigo maligna to lentigo maligna melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116(3):303–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb05843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazan C, Dusza SW, Delgado R, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, Nehal KS. Staged excision for lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma: a retrospective analysis of 117 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somach SC, Taira JW, Pitha JV, Everett MA. Pigmented lesions in actinically damaged skin. Histopathologic comparison of biopsy and excisional specimens. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(11):1297–1302. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1996.03890350035006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosbous MW, Dzwierzynski WW, Neuburg M. Staged excision of lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma: a 10-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(6):1947–1955. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bcf002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGuire LK, Disa JJ, Lee EH, Busam KJ, Nehal KS. Melanoma of the lentigo maligna subtype: diagnostic challenges and current treatment paradigms. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(2):288e–299e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31823aeb72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kvaskoff M, Siskind V, Green AC. Risk factors for lentigo maligna melanoma compared with superficial spreading melanoma: a case-control study in Australia. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(2):164–170. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swetter SM, Boldrick JC, Jung SY, Egbert BM, Harvell JD. Increasing incidence of lentigo maligna melanoma subtypes: northern California and national trends 1990–2000. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(4):685–691. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akay BN, Kocyigit P, Heper AO, Erdem C. Dermatoscopy of flat pigmented facial lesions: diagnostic challenge between pigmented actinic keratosis and lentigo maligna. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(6):1212–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lallas A, Argenziano G, Moscarella E, Longo C, Simonetti V, Zalaudek I. Diagnosis and management of facial pigmented macules. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(1):94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zalaudek I, Cota C, Ferrara G, Moscarella E, Guitera P, Longo C, et al. Flat pigmented macules on sun-damaged skin of the head/neck: junctional nevus, atypical lentiginous nevus, or melanoma in situ? Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(1):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kallini JR, Jain SK, Khachemoune A. Lentigo maligna: review of salient characteristics and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14(6):473–480. doi: 10.1007/s40257-013-0044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rigel D, Robinson JK, Ross M, Friedman RJ, Cockerell CJ, Lim HW, Stockfleth E. Cancer of the Skin. Edinburgh, New York: Saunders; 2011. ISBN 978-1-4377-1788-4.

- 18.Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg Off Pub Am Soc Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(9):1099–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung HJ, McGuigan KL, Osley KL, Zendell K, Lee JB. Pigmented solar (actinic) keratosis: an underrecognized collision lesion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4):647–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pock L, Drlik L, Hercogova J. Dermatoscopy of pigmented actinic keratosis–a striking similarity to lentigo maligna. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(4):414–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uhlenhake EE, Sangueza OP, Lee AD, Jorizzo JL. Spreading pigmented actinic keratosis: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(3):499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pralong P, Bathelier E, Dalle S, Poulalhon N, Debarbieux S, Thomas L. Dermoscopy of lentigo maligna melanoma: report of 125 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(2):280–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, Talamini R, Corona R, Sera F, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: results of a consensus meeting via the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(5):679–693. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stolz W, Schiffner R, Burgdorf WH. Dermatoscopy for facial pigmented skin lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20(3):276–278. doi: 10.1016/S0738-081X(02)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross EA, Andersen WK, Rogers GS. Mohs micrographic excision of lentigo maligna using Mel-5 for margin control. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135(1):15–17. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed JA, Shea CR. Lentigo maligna: melanoma in situ on chronically sun-damaged skin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135(7):838–841. doi: 10.5858/2011-0051-RAIR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Florell SR, Boucher KM, Leachman SA, Azmi F, Harris RM, Malone JC, et al. Histopathologic recognition of involved margins of lentigo maligna excised by staged excision: an interobserver comparison study. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(5):595–604. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.5.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mir M, Chan CS, Khan F, Krishnan B, Orengo I, Rosen T. The rate of melanoma transection with various biopsy techniques and the influence of tumor transection on patient survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(3):452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wigger-Alberti W, Elsner P. Fluorescence with Wood’s light. Current applications in dermatologic diagnosis, therapy follow-up and prevention. Der Hautarzt Zeitschrift Dermatol Venerol Verwandte Geb. 1997;48(8):523–527. doi: 10.1007/s001050050622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorman M, Khan MA, Johnson PC, Hart A, Mathew B. A model for lentigo maligna recurrence using melanocyte count as a predictive marker based upon logistic regression analysis of a blinded retrospective review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg JPRAS. 2014;67(10):1322–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El Tal AK, Abrou AE, Stiff MA, Mehregan DA. Immunostaining in Mohs micrographic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg Off Pub Am Soc Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(3):275–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, Binder SW. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(5):433–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magro CM, Crowson AN, Desman G, Zippin JH. Soluble adenylyl cyclase antibody profile as a diagnostic adjunct in the assessment of pigmented lesions. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(3):335–344. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magro CM, Yang SE, Zippin JH, Zembowicz A. Expression of soluble adenylyl cyclase in lentigo maligna: use of immunohistochemistry with anti-soluble adenylyl cyclase antibody (R21) in diagnosis of lentigo maligna and assessment of margins. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(12):1558–1564. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2011-0617-OA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLeod M, Choudhary S, Giannakakis G, Nouri K. Surgical treatments for lentigo maligna: a review. Dermatol Surg Off Pub Am Soc Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(9):1210–1228. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunishige JH, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Surgical margins for melanoma in situ. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(3):438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cramer SF, Kiehn CL. Sequential histologic study of evolving lentigo maligna melanoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1982;106(3):121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bene NI, Healy C, Coldiron BM. Mohs micrographic surgery is accurate 95.1% of the time for melanoma in situ: a prospective study of 167 cases. Dermatol Surg Off Pub Am Soc Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(5):660–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhawan J. Mel-5: a novel antibody for differential diagnosis of epidermal pigmented lesions of the skin in paraffin-embedded sections. Melanoma Res. 1997;7(1):43–48. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199702000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abdelmalek M, Loosemore MP, Hurt MA, Hruza G. Geometric staged excision for the treatment of lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma: a long-term experience with literature review. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(5):599–604. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaudy-Marqueste C, Perchenet AS, Tasei AM, Madjlessi N, Magalon G, Richard MA, et al. The “spaghetti technique”: an alternative to Mohs surgery or staged surgery for problematic lentiginous melanoma (lentigo maligna and acral lentiginous melanoma) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(1):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson TM, Headington JT, Baker SR, Lowe L. Usefulness of the staged excision for lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma: the “square” procedure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5 Pt 1):758–764. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(97)70114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahoney MH, Joseph M, Temple CL. The perimeter technique for lentigo maligna: an alternative to Mohs micrographic surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91(2):120–125. doi: 10.1002/jso.20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moller MG, Pappas-Politis E, Zager JS, Santiago LA, Yu D, Prakash A, et al. Surgical management of melanoma-in situ using a staged marginal and central excision technique. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(6):1526–1536. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brodland DG. Reconstruction conundrum #3. Excision and reconstruction of recurrent lentigo maligna melanoma. Dermatol Surg Off Pub Am Soc Dermatol Surg. 2000;26(10):965–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.026010965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevenson O, Ahmed I. Lentigo maligna: prognosis and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(3):151–164. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200506030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Erickson C, Miller SJ. Treatment options in melanoma in situ: topical and radiation therapy, excision and Mohs surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(5):482–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fogarty GB, Hong A, Scolyer RA, Lin E, Haydu L, Guitera P, et al. Radiotherapy for lentigo maligna—a literature review and recommendations for treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/bjd.12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hedblad MA, Mallbris L. Grenz ray treatment of lentigo maligna and early lentigo maligna melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(1):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLeod M, Franca K, Ferris K, Nouri K. Use of carbon dioxide laser to treat lentigo maligna and malignant melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2012;14(6):462. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2012.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Madan V, August PJ. Lentigo maligna—outcomes of treatment with Q-switched Nd:YAG and alexandrite lasers. Dermatol Surg Off Pub Am Soc Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(4):607–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karam A, Simon M, Lemasson G, Misery L. The use of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of lentigo maligna. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2013;26(2):275–277. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong JG, Toole JW, Demers AA, Musto G, Wiseman MC. Topical 5% imiquimod in the treatment of lentigo maligna. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16(4):245–249. doi: 10.1177/120347541201600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rajpar SF, Marsden JR. Imiquimod in the treatment of lentigo maligna. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(4):653–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lapresta A, Garcia-Almagro D, Sejas AG. Amelanotic lentigo maligna managed with topical imiquimod. The J Dermatol. 2012;39(5):503–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolf IH, Cerroni L, Kodama K, Kerl H. Treatment of lentigo maligna (melanoma in situ) with the immune response modifier imiquimod. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(4):510–514. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.4.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.NIH. National Cancer Institute. 2012. http://www.cancer.gov/. Accessed Dec 30 2013.

- 58.Schmitt JV, Miot HA. Actinic keratosis: a clinical and epidemiological revision. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87(3):425–434. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962012000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hyde MA, Hadley ML, Tristani-Firouzi P, Goldgar D, Bowen GM. A randomized trial of the off-label use of imiquimod, 5%, cream with vs without tazarotene, 0.1%, gel for the treatment of lentigo maligna, followed by conservative staged excisions. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(5):592–596. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ly L, Kelly JW, O’Keefe R, Sutton T, Dowling JP, Swain S, et al. Efficacy of imiquimod cream, 5%, for lentigo maligna after complete excision: a study of 43 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(10):1191–1195. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Vries K, Rellum R, Habets JM, Prens EP. A novel two-stage treatment of lentigo maligna using ablative laser therapy followed by imiquimod. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(6):1362–1364. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bassukas ID, Gamvroulia C, Zioga A, Nomikos K, Fotika C. Cryosurgery during topical imiquimod: a successful combination modality for lentigo maligna. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(5):519–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]