Abstract

Bacteria possess many kinases that catalyze phosphorylation of proteins on diverse amino acids including arginine, cysteine, histidine, aspartate, serine, threonine, and tyrosine. These protein kinases regulate different physiological processes in response to environmental modifications. For example, in response to nutritional stresses, the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis can differentiate into an endospore; the initiation of sporulation is controlled by the master regulator Spo0A, which is activated by phosphorylation. Spo0A phosphorylation is carried out by a multi-component phosphorelay system. These phosphorylation events on histidine and aspartate residues are labile, highly dynamic and permit a temporal control of the sporulation initiation decision. More recently, another kind of phosphorylation, more stable yet still dynamic, on serine or threonine residues, was proposed to play a role in spore maintenance and spore revival. Kinases that perform these phosphorylation events mainly belong to the Hanks family and could regulate spore dormancy and spore germination. The aim of this mini review is to focus on the regulation of sporulation in B. subtilis by these serine and threonine phosphorylation events and the kinases catalyzing them.

Keywords: Ser/Thr protein kinases, phosphorylation, regulation, sporulation, Bacillus subtilis

Introduction

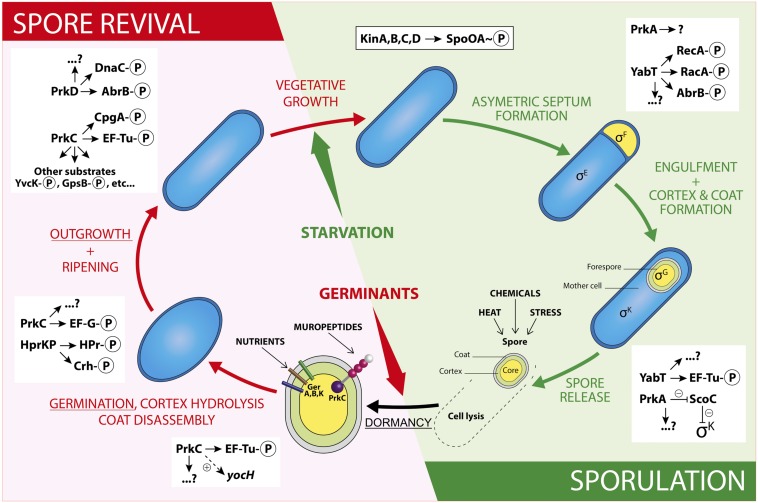

Many Gram-positive bacteria form endospores in response to stress or nutrient limitation (Stragier and Losick, 1996; Higgins and Dworkin, 2012). Spores are morphologically distinct cells that are highly resistant to heat, chemicals, and radiation (Nicholson et al., 2000; Setlow, 2003, 2006, 2008). These dormant cells are able to reinitiate growth rapidly in response to environmental signals like amino acids or cell-wall muropeptides released by growing cells (Setlow, 2003, 2008). These processes are well regulated and orchestrated by a series of protein phosphorylation events and changes in gene expressions controlled by sigma factors (σE, σF, σG and σK). In Bacillus subtilis, a landmark of the initiation of sporulation is the activation of the transcriptional master regulator Spo0A. It is activated by phosphorylation through a remarkable multi-component phosphorelay system of autophosphorylating histidine kinases (KinA-KinE) (Burbulys et al., 1991; LeDeaux et al., 1995; Tan and Ramamurthi, 2014). These phosphorylations are labile and highly dynamic, thus permitting a temporal regulation of the sporulation initiation decision (De Jong et al., 2010). More recently, another kind of phosphorylation, more stable yet still dynamic, on serine or threonine residues of protein substrates, has been proposed to play a role in sporulation (Cousin et al., 2013). These phosphorylation reactions are generally catalyzed by Ser/Thr protein kinases (STPKs) of the Hanks family (Hanks and Hunter, 1995). They seem to regulate entry into sporulation, dormancy, and spore revival. These kinases share a common fold for their cytosolic catalytic domain typically composed of 12 subdomains organized in two-lobes surrounding the active site (Kornev and Taylor, 2010). In some STPKs, the kinase domain is attached to a transmembrane helix connected to an extracellular ligand binding domain responsible for kinase activation. In some, the kinase domain is connected to a transmembrane helix without any extracellular domain. In others, the kinase domain is soluble. They are themselves activated by autophosphorylation on Ser or Thr residues of their activation loop (Pereira et al., 2011). In addition, each kinase is able to phosphorylate various substrates on Ser and/or Thr residues. In B. subtilis, four Ser/Thr kinases of the Hanks family have been characterized to date: PrkA, PrkC, PrkD, and YabT. All of them, except PrkD, are implicated at different levels of the sporulation process: onset, dormancy, germination, and outgrowth (Figure 1) (Shah et al., 2008; Bidnenko et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2015). Several phosphoproteome studies have been performed during the last 10 years and thanks to technical progress especially in mass spectrometry, more and more phosphorylated proteins have been identified in B. subtilis (Eymann et al., 2007; Macek et al., 2007; Soufi et al., 2010; Kobir et al., 2011; Ravikumar et al., 2014; Rosenberg et al., 2015). In early studies, only one experimental condition was probed. Nowadays, dynamic phosphoproteomes can be analyzed, and allow to explore several growth conditions for the same bacterial population. Furthermore, it has recently been proposed that cross-talks exist between two-component systems and STPKs as well as cross-phosphorylations among STPKs (Pereira et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2014a). This network of regulations may also be complicated by cross-talk with bacterial tyrosine kinases (BY-kinases) (Cousin et al., 2013). Such a complex regulatory network could allow quick and efficient regulation of bacterial physiology in response to the environmental variations. Broadly, the role of phosphorylation in several bacterial processes like DNA-related mechanisms, cell division and morphogenesis have been discussed recently (Garcia-Garcia et al., 2016; Manuse et al., 2016). In this review, we will specially focus on regulations mediated by STPKs during the different stages of sporulation in the model bacterium B. subtilis.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic illustration of regulations by Ser/Thr phosphorylation during a Bacillus subtilis spore life. The sporulation steps are presented in the green panel and the spore revival steps in the red panel. The stages described in the review are underlined. In the schematic spore, the core is in yellow, the cortex in green and the coat in gray. The two types of spore signal receptors are represented: the GerA, B, and K in sticks, the STPK PrkC in balls (purple: kinase domain, pink: PASTA domains, and white: IgG-like domain) and stick (transmembrane domain). For a detailed structure of a STPK, see (Pereira et al., 2011). For examples of PrkC substrates identified during vegetative growth, see references (Foulquier et al., 2014; Pompeo et al., 2015). The two-component cascade leading to Spo0A phosphorylation is presented in the framed rectangle and regulations by STPKs are listed in the white rectangles. Other possible cross-regulations by two-component systems, BY-kinases, or other phosphorylations are not represented here in order to not overload the drawing.

Sporulation

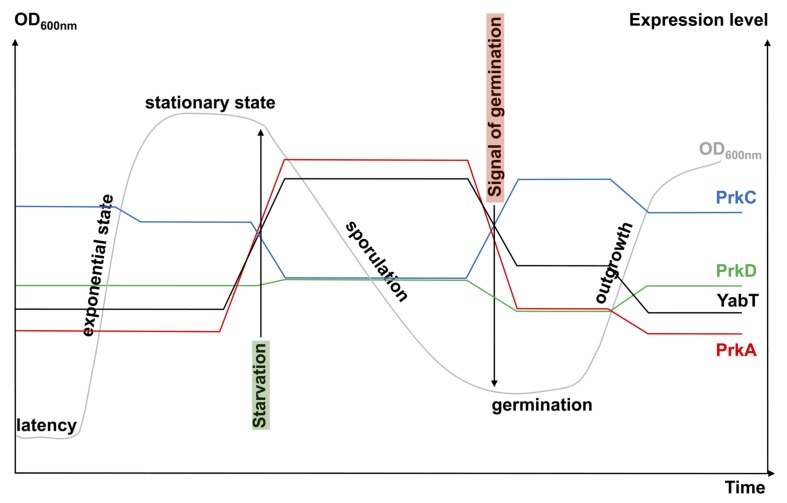

Sporulation is a morphological differentiation event that is initiated by an asymmetric division yielding a smaller forespore and a larger mother cell (Stragier and Losick, 1996; Higgins and Dworkin, 2012). Several steps are necessary from the formation of a forespore to the release of a mature spore after lysis of the mother cell. These include engulfment, cortex synthesis and coat formation (Figure 1) in order to confer to the spore the resistance properties required to survive extreme conditions of temperature, desiccation and ionization (Setlow, 2006). This robustness is the result of several factors like dehydration, DNA compaction, and dormant metabolism (Nicholson et al., 2000; Setlow, 2007; Camp and Losick, 2009; Doan et al., 2009). As mentioned before, initiation of sporulation is controlled by a cascade of phosphorylation events catalyzed by two-component systems and eventually leading to the activation of Spo0A. When the level of Spo0A-P is sufficient (Vishnoi et al., 2013), the compartment-specific transcription factor σF is activated, definitely engaging the sporulating cell into a specific program of genes expression (Tan and Ramamurthi, 2014). In addition, the expression of two genes encoding the STPKs PrkA and YabT increases strongly during sporulation under the control of the spore-specific sigma factors, σE and σF, respectively (Figure 2). These two kinases have been indeed shown to participate in the regulation of several mechanisms occurring during the initiation of sporulation (Fischer et al., 1996; Bidnenko et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2015). PrkA is a STPK that only possesses a catalytical domain and localizes in the coat of the forespore (Eichenberger et al., 2003). This protein also shows a distant homology to eukaryotic cAMP-dependent protein kinases and several essential residues of their active site are apparently conserved in PrkA. Using a B. subtilis crude extract, it has been proposed that PrkA phosphorylates an unidentified 60-kDa protein on Ser residue(s) (Fischer et al., 1996). However, no PrkA autophosphorylation was detected. That is surprising since STPKs generally need to be autophosphorylated to be active. However, even if the enzymatic properties of PrkA are poorly characterized, the role of this protein in sporulation seems clearly established. Actually, deletion of prkA gene leads to a sporulation defect corresponding to a delay in the entry into sporulation and a decrease in the number of spores. It has recently been shown that PrkA was involved in the synthesis of the σK transcription factor (Yan et al., 2015). Indeed, PrkA increases the expression of σK and its downstream target genes, by inhibiting the negative transcriptional regulator ScoC (Hpr) (Figure 1). However, the complete mechanism of regulation, potentially via the kinase activity of PrkA, is not known: how does PrkA act on ScoC? Is it a direct or indirect regulation of ScoC and does PrkA phosphorylate ScoC on Ser/Thr residue(s)? What are the exact targets of PrkA phosphorylation? Though it appears that PrkA is a key player in the regulation of sporulation in B. subtilis, more work needs to be done in order to completely understand the role of this putative STPK. The second regulatory protein YabT is a STPK containing three domains: a transmembrane region, a kinase domain and a DNA-binding domain. YabT kinase activity has been clearly established and targets of YabT have been identified. Binding of YabT to DNA activates its kinase activity; YabT is then able to autophosphorylate and to phosphorylate exogenous substrates (Bidnenko et al., 2013). It colocalizes with the septal inner membrane separating the forespore from the mother cell. As for prkA, deletion of the yabT gene leads to a sporulation delay. Furthermore, resistance to DNA damages decreases in the yabT mutant spores. Both phenotypes were also observed in a recA mutant (Shafikhani et al., 2004; Bidnenko et al., 2013). The recombinase RecA is actually a YabT substrate in vitro (phosphorylation on Ser2) and consistently, RecA was previously identified in a phosphoproteome study revealing the same phosphorylated residue (Soufi et al., 2010). It is, therefore, likely that YabT regulates RecA activity in the forespore in order to allow DNA damage repair before nucleoid compaction in the spore (Sciochetti et al., 2001). Similarities between the bacterial STPK YabT and the eukaryotic STPKs C-Abl and Mec1 have been found: all these kinases are activated by DNA and phosphorylate proteins involved in DNA damage repair mechanisms (Bidnenko et al., 2013). In vitro, YabT is able to phosphorylate RacA, another DNA-related protein involved in DNA anchoring to the cell pole (Ben-Yehuda et al., 2003; Shi et al., 2014b). RacA can be dephosphorylated in vitro by SpoIIE, a serine protein phosphatase known to modulate the phosphorylation state of the anti-anti σF factor SpoIIAA (Arigoni et al., 1996). Interestingly, YabT and SpoIIE have been found associated to the same protein partners in a recent yeast two-hybrid screen suggesting that they function as a kinase/phosphatase couple during sporulation (Shi et al., 2014b). Another potential substrate of YabT is the global transcriptional regulator AbrB which is phosphorylated on Ser86 in vivo (Figure 1) (Soufi et al., 2010) as well as in vitro by YabT, PrkC and PrkD (Kobir et al., 2014). AbrB is a global gene regulator involved in transition phases (i.e., from exponential to stationary growth phase) that also antagonizes sporulation by repressing the expression of Spo0A (Phillips and Strauch, 2002). It has been proposed that AbrB phosphorylation serves as an additional input for a subtle control of AbrB activity. Indeed, AbrB phosphorylation inhibits its ability to bind its DNA targets (Kobir et al., 2014). In addition, a strain expressing phospho-mimetic AbrB produces fewer spores and sporulates much slower. Because the YabT kinase is produced just after the onset of sporulation, it is the best candidate for AbrB phosphorylation in sporulation conditions.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic view of STPK gene expression during growth. The growth curve of a B. subtilis cell culture in rich medium is presented in gray (OD600nm). The levels of kinase gene expression are obtained from http://subtiwiki.uni-goettingen.de/ (Michna et al., 2016) and from Nicolas et al. (2012). They are presented in color: blue for prkC, green for prkD, red for prkA, and black for yabT. Signals for starvation (highlighted in green) and germination (highlighted in red) are indicated by arrows.

Dormancy

It is commonly accepted that when the mature spore is released by the mother cell, it is metabolically dormant and environmentally resistant. The spore is protected by thick layers: the cortex and the coat, and contains a high level of dipicolinic acid (DPA) and a low amount of water. However, it has been recently shown that the spore RNA profile is highly dynamic a few days following sporulation (Segev et al., 2012). During this short period, spores are responsive to environmental changes and can adapt their RNA content consequently. Furthermore, some enzymatic activities necessary for full maturation of coat proteins have been described in spores (Zilhão et al., 2005; Sanchez-Salas et al., 2011). Taking these observations into account, it is possible to consider that regulation of enzymatic activities or protein synthesis by phosphorylation reactions exist in spore during this adaptive period. For example, the overall metabolism is down regulated, in particular protein synthesis, which is an energy-intensive cellular process. This regulation is mediated by phosphorylation of the elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu). Indeed, phosphorylated EF-Tu is unable to hydrolyze GTP and remains bound to the ribosome which leads to a dominant-negative effect in elongation, thus inhibiting protein synthesis (Pereira et al., 2015). It has been proposed that the kinase involved in this phosphorylation is YabT because it is present in the spore during dormancy and it is able to phosphorylate EF-Tu in vitro on Thr63. In vivo experiments confirmed that YabT is responsible of EF-Tu phosphorylation in the spore since no phosphorylated EF-Tu was found in a yabT mutant (Figure 1) (Pereira et al., 2015). Moreover, in vitro phosphorylation of EF-Tu by PrkC was previously reported on Thr384 but the in vivo regulatory function of this phosphorylation has not been accounted for so far (Absalon et al., 2009).

Germination and Outgrowth

Spores of B. subtilis can remain dormant for years but return to life quickly after exposure to nutrients or muropeptides (Setlow, 2003, 2008, 2014). Specific receptors (including GerA, GerB, and GerK) that detect nutrients have been known for years (Atluri et al., 2006; Ramirez-Peralta et al., 2013). More recently, in the inner spore membrane, the STPK PrkC has been shown to bind muropeptides released by growing cells thus inducing germination (Shah et al., 2008). Spores can also reinitiate growth stochastically at a low frequency due to phenotypic variations in individual spore (Sturm and Dworkin, 2015). The revival process (Figure 1) can be divided into three consecutive phases: (i) germination with spore rehydration, release of DPA, cortex hydrolysis, and coat disassembly, then (ii) a ripening period with no morphological changes but a molecular reorganization of the cell, and finally (iii) outgrowth with synthesis of macromolecules, membrane elongation, and cell division (Sinai et al., 2015). However, it seems that synthesis of proteins might start earlier, as early as 30 min after the initiation of germination. Up to 650 new proteins are synthesized during the three steps described above (Sinai et al., 2015). A dynamic phosphoproteome of reviving spores established a functional connection between Ser/Thr/Tyr-phosphorylation and progression of this process (Rosenberg et al., 2015). Though it was proposed that the STPK PrkC, and, therefore, phosphorylation of PrkC protein substrates, stimulates germination only in the presence of muropeptides as germinant (Shah et al., 2008), this phosphoproteome analysis was only done in the presence of L-Ala as germinant. It will be interesting to perform the same study using muropeptides as germinant to compare the profile of phosphorylated proteins identified. Nevertheless, the high number of new phosphoproteins already characterized (Rosenberg et al., 2015) suggests an important modulation of protein activity during this cellular transition to vegetative growth. The phosphoproteins identified are involved in spore-specific functions, transcription, metabolism, and stress response, some of which are probably phosphorylated by STPKs. YabT and PrkA are highly synthesized during sporulation whereas PrkC is more expressed during germination (Figure 2). However, these three kinases and possibly other still unknown protein kinases (with weak homology to classical STPK) could contribute to these regulatory mechanisms. PrkC is a transmembrane protein composed of an intracellular catalytic domain and an extracellular regulatory C-terminal region containing several beta-lactam-binding domains. These PASTA domains (for penicillin-binding protein and serine/threonine kinase-associated domains) are predicted to interact with the peptidoglycan (PG) (Yeats et al., 2002). Biochemical studies of PrkC homologues confirmed the in vitro interaction between PG fragments and PrkC (Mir et al., 2011; Ruggiero et al., 2011; Squeglia et al., 2011). Thus, binding of PG fragments released from growing cells to the extracellular domain of PrkC could stimulate PrkC kinase activity to induce the germination of the spore (Figure 1) (Shah et al., 2008). The prkC gene expression is low during sporulation and stimulated during germination but its expression level during vegetative growth and especially during stationary phase is not negligible (Figure 2). Hence, PrkC can phosphorylate several substrates produced during vegetative growth or sporulation and, up to now, more than 10 substrates of PrkC have been identified in vitro. These targets include proteins of carbon metabolism (Pietack et al., 2010) or proteins involved in protein synthesis like CpgA, a GTPase involved in a late stage of ribosome assembly, and the elongation factors EF-G and EF-Tu (Shah et al., 2008; Absalon et al., 2009; Pompeo et al., 2012). It has beeen proposed that PrkC phosphorylates EF-G in the spore to allow re-initiation of protein synthesis. But, it is unlikely that this phosphorylation is the only cause of germination. PrkC also promotes the expression of yocH, a muralytic enzyme encoding gene. YocH is exported and digests the PG of other growing bacteria, thus producing more muropeptides that in turn stimulate germination (Shah and Dworkin, 2010; Libby et al., 2015). Moreover, the phosphorylation of several proteins has been shown to be important for germination. These include the spore specific proteins SspA et SspB involved in DNA protection, the ribosomal protein RpsJ, the elongation factors EF-Tu and EF-G, and the phosphocarrier protein HPr (Rosenberg et al., 2015). But, for many of them, the kinase that catalyzes their phosphorylation is still unknown. In the particular case of HPr, which is a component of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar system (PTS) and a key player of carbon catabolite regulation in B. subtilis, phosphorylation is catalyzed by HprK/P, an atypical ATP-dependent kinase/phosphorylase. This enzyme does not share homology with eukaryotic STPKs and does not belong to the Hanks kinase family. Instead, it shares limited homology with the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Galinier et al., 2002). It does not autophosphorylate but phosphorylates two protein substrates, HPr and its homologue Crh, on the Ser46 residue (Galinier et al., 1997, 1998). HprK/P is stimulated by phosphorylated sugars like glucose 6-phosphate or fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (Jault et al., 2000) for the regulation of carbohydrate utilization (Galinier et al., 1998; Martin-Verstraete et al., 1999). However, during spore revival, it may be activated in the presence of alternative PTS sugars (Rosenberg et al., 2015). In addition, strains producing some HPr mutant proteins on the Ser46 phosphorylation site (both phosphoablative and phosphomimetic mutants) exhibited reduced sporulation efficiency (Rosenberg et al., 2015). These results indicate that the phosphorylation level of HPr is important for spore revival. This is not surprising since optimal carbon utilization needs to take place rapidly upon revival. Therefore, the regulation of spore revival by phosphorylation on Ser and Thr residues is an important mechanism that can be mediated by several types of kinases like STPKs and HprK/P, or even other atypical protein kinases not yet identified. This network of regulations may also be complicated by cross-talk with other phosphorylation systems like BY-kinases (Cousin et al., 2013), two-component systems, or recently identified Arg phosphorylations (Elsholz et al., 2012; Schmidt et al., 2014).

Conclusion

It is now widely accepted that regulatory Ser/Thr phosphorylation is as present in prokaryotes as in eukaryotes and that enzymes responsible for these modifications are mainly eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr kinases. To date, four of these proteins have been characterized in B. subtilis (PrkA, PrkC, PrkD, and YabT) and several examples highlight their regulatory role in cellular physiology during vegetative growth as well as during sporulation. In this mini review, we focused on their regulatory functions in spores and showed that STPKs have relaxed substrate selectivity that confers to the cell a quick way to adapt to the physiological conditions. Taking into account that cross-phosphorylation events occur among STPKs, BY-kinases, and two-component systems, the regulatory network controlling a spore life is highly dynamic and sophisticated. Given the role of spores in many diseases, understanding mechanisms and regulation of spore formation and spore germination has long been a researcher’s interest in order to find a way to get rid of them more efficiently. However, a new interest has now emerged with the use of spores as a tool in biotechnology (Isticato and Ricca, 2014).

Author Contributions

All authors listed, have made substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank J.R. Fantino for drawings with Adobe Illustrator and T. Doan for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank B. Khadaroo and the reviewers for English proofreading.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by the CNRS, the ANR (ANR-12-BSV3-0008-01), and Aix-Marseille University.

References

- Absalon C., Obuchowski M., Madec E., Delattre D., Holland I. B., Seror S. J. (2009). CpgA, EF-Tu and the stressosome protein YezB are substrates of the Ser/Thr kinase/phosphatase couple, PrkC/PrpC, in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 155 932–943. 10.1099/mic.0.022475-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arigoni F., Duncan L., Alper S., Losick R., Stragier P. (1996). SpoIIE governs the phosphorylation state of a protein regulating transcription factor sigma F during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 3238–3242. 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri S., Ragkousi K., Cortezzo D. E., Setlow P. (2006). Cooperativity between different nutrient receptors in germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis and reduction of this cooperativity by alterations in the GerB receptor. J. Bacteriol. 188 28–36. 10.1128/JB.188.1.28-36.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yehuda S., Rudner D. Z., Losick R. (2003). RacA, a bacterial protein that anchors chromosomes to the cell poles. Science 299 532–536. 10.1126/science.1079914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidnenko V., Shi L., Kobir A., Ventroux M., Pigeonneau N., Henry C., et al. (2013). Bacillus subtilis serine/threonine protein kinase YabT is involved in spore development via phosphorylation of a bacterial recombinase. Mol. Microbiol. 88 921–935. 10.1111/mmi.12233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbulys D., Trach K. A., Hoch J. A. (1991). Initiation of sporulation in B. subtilis is controlled by a multicomponent phosphorelay. Cell 64 545–552. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90238-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp A. H., Losick R. (2009). A feeding tube model for activation of a cell-specific transcription factor during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 23 1014–1024. 10.1101/gad.1781709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousin C., Derouiche A., Shi L., Pagot Y., Poncet S., Mijakovic I. (2013). Protein-serine/threonine/tyrosine kinases in bacterial signaling and regulation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 346 11–19. 10.1111/1574-6968.12189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong I. G., Veening J. W., Kuipers O. P. (2010). Heterochronic phosphorelay gene expression as a source of heterogeneity in Bacillus subtilis spore formation. J. Bacteriol. 192 2053–2067. 10.1128/JB.01484-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan T., Morlot C., Meisner J., Serrano M., Henriques A. O., Moran C. P., et al. (2009). Novel secretion apparatus maintains spore integrity and developmental gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000566 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberger P., Jensen S. T., Conlon E. M., Van Ooij C., Silvaggi J., González-Pastor J. E., et al. (2003). The sigmaE regulon and the identification of additional sporulation genes in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 327 945–972. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00205-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsholz A. K., Turgay K., Michalik S., Hessling B., Gronau K., Oertel D., et al. (2012). Global impact of protein arginine phosphorylation on the physiology of Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 7451–7456. 10.1073/pnas.1117483109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eymann C., Becher D., Bernhardt J., Gronau K., Klutzny A., Hecker M. (2007). Dynamics of protein phosphorylation on Ser/Thr/Tyr in Bacillus subtilis. Proteomics 7 3509–3526. 10.1002/pmic.200700232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C., Geourjon C., Bourson C., Deutscher J. (1996). Cloning and characterization of the Bacillus subtilis prkA gene encoding a novel serine protein kinase. Gene 168 55–60. 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00758-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulquier E., Pompeo F., Freton C., Cordier B., Grangeasse C., Galinier A. (2014). PrkC-mediated phosphorylation of overexpressed YvcK protein regulates PBP1 protein localization in Bacillus subtilis mreB mutant cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289 23662–23669. 10.1074/jbc.M114.562496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinier A., Haiech J., Kilhoffer M. C., Jaquinod M., Stulke J., Deutscher J., et al. (1997). The Bacillus subtilis crh gene encodes a HPr-like protein involved in carbon catabolite repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 8439–8444. 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinier A., Kravanja M., Engelmann R., Hengstenberg W., Kilhoffer M. C., Deutscher J., et al. (1998). New protein kinase and protein phosphatase families mediate signal transduction in bacterial catabolite repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 1823–1828. 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinier A., Lavergne J. P., Geourjon C., Fieulaine S., Nessler S., Jault J. M. (2002). A new family of phosphotransferases with a P-loop motif. J. Biol. Chem. 277 11362–11367. 10.1074/jbc.M109527200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Garcia T., Poncet S., Derouiche A., Shi L., Mijakovic I., Noirot-Gros M. F. (2016). Role of protein phosphorylation in the regulation of cell cycle and DNA-related processes in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 7:184 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks S. K., Hunter T. (1995). Protein kinases 6. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J. 9 576–596. 10.1016/B978-012324719-3/50003-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D., Dworkin J. (2012). Recent progress in Bacillus subtilis sporulation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36 131–148. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00310.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isticato R., Ricca E. (2014). Spore surface display. Microbiol. Spectr. 2 1–15. 10.1128/microbiolspec.TBS-0011-2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jault J. M., Fieulaine S., Nessler S., Gonzalo P., Di Pietro A., Deutscher J., et al. (2000). The HPr kinase from Bacillus subtilis is a homo-oligomeric enzyme which exhibits strong positive cooperativity for nucleotide and fructose 1,6-bisphosphate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 275 1773–1780. 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobir A., Poncet S., Bidnenko V., Delumeau O., Jers C., Zouhir S., et al. (2014). Phosphorylation of Bacillus subtilis gene regulator AbrB modulates its DNA-binding properties. Mol. Microbiol. 92 1129–1141. 10.1111/mmi.12617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobir A., Shi L., Boskovic A., Grangeasse C., Franjevic D., Mijakovic I. (2011). Protein phosphorylation in bacterial signal transduction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1810 989–994. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornev A. P., Taylor S. S. (2010). Defining the conserved internal architecture of a protein kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804 440–444. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDeaux J. R., Yu N., Grossman A. D. (1995). Different roles for KinA, KinB, and KinC in the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177 861–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby E. A., Goss L. A., Dworkin J. (2015). The eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr Kinase PrkC regulates the essential WalRK two-component system in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005275 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macek B., Mijakovic I., Olsen J. V., Gnad F., Kumar C., Jensen P. R., et al. (2007). The serine/threonine/tyrosine phosphoproteome of the model bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Cell Proteomics 6 697–707. 10.1074/mcp.M600464-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuse S., Fleurie A., Zucchini L., Lesterlin C., Grangeasse C. (2016). Role of eukaryotic-like serine/threonine kinases in bacterial cell division and morphogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40 41–56. 10.1093/femsre/fuv041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Verstraete I., Deutscher J., Galinier A. (1999). Phosphorylation of HPr and Crh by HprK, early steps in the catabolite repression signalling pathway for the Bacillus subtilis levanase operon. J. Bacteriol. 181 2966–2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michna R. H., Zhu B., Mäder U., Stülke J. (2016). SubtiWiki 2.0-an integrated database for the model organism Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D654–D662. 10.1093/nar/gkv1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir M., Asong J., Li X., Cardot J., Boons G. J., Husson R. N. (2011). The extracytoplasmic domain of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ser/Thr kinase PknB binds specific muropeptides and is required for PknB localization. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002182 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson W. L., Munakata N., Horneck G., Melosh H. J., Setlow P. (2000). Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64 548–572. 10.1128/MMBR.64.3.548-572.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas P., Mäder U., Dervyn E., Rochat T., Leduc A., Pigeonneau N., et al. (2012). Condition-dependent transcriptome reveals high-level regulatory architecture in Bacillus subtilis. Science 335 1103–1106. 10.1126/science.1206848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira S. F., Gonzalez R. L., Dworkin J. (2015). Protein synthesis during cellular quiescence is inhibited by phosphorylation of a translational elongation factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 E3274–E3281. 10.1073/pnas.1505297112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira S. F., Goss L., Dworkin J. (2011). Eukaryote-like serine/threonine kinases and phosphatases in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75 192–212. 10.1128/MMBR.00042-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips Z. E., Strauch M. A. (2002). Bacillus subtilis sporulation and stationary phase gene expression. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 59 392–402. 10.1007/s00018-002-8431-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietack N., Becher D., Schmidl S. R., Saier M. H., Hecker M., Commichau F. M., et al. (2010). In vitro phosphorylation of key metabolic enzymes from Bacillus subtilis: PrkC phosphorylates enzymes from different branches of basic metabolism. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18 129–140. 10.1159/000308512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompeo F., Foulquier E., Serrano B., Grangeasse C., Galinier A. (2015). Phosphorylation of the cell division protein GpsB regulates PrkC kinase activity through a negative feedback loop in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 97 139–150. 10.1111/mmi.13015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompeo F., Freton C., Wicker-Planquart C., Grangeasse C., Jault J. M., Galinier A. (2012). Phosphorylation of CpgA protein enhances both its GTPase activity and its affinity for ribosome and is crucial for Bacillus subtilis growth and morphology. J. Biol. Chem. 287 20830–20838. 10.1074/jbc.M112.340331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Peralta A., Gupta S., Butzin X. Y., Setlow B., Korza G., Leyva-Vazquez M. A., et al. (2013). Identification of new proteins that modulate the germination of spores of Bacillus species. J. Bacteriol. 195 3009–3021. 10.1128/JB.00257-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar V., Shi L., Krug K., Derouiche A., Jers C., Cousin C., et al. (2014). Quantitative phosphoproteome analysis of Bacillus subtilis reveals novel substrates of the kinase PrkC and phosphatase PrpC. Mol. Cell Proteomics 13 1965–1978. 10.1074/mcp.M113.035949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg A., Soufi B., Ravikumar V., Soares N. C., Krug K., Smith Y., et al. (2015). Phosphoproteome dynamics mediate revival of bacterial spores. BMC Biol. 13:76 10.1186/s12915-015-0184-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero A., Squeglia F., Marasco D., Marchetti R., Molinaro A., Berisio R. (2011). X-ray structural studies of the entire extracellular region of the serine/threonine kinase PrkC from Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem. J. 435 33–41. 10.1042/BJ20101643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Salas J. L., Setlow B., Zhang P., Li Y. Q., Setlow P. (2011). Maturation of released spores is necessary for acquisition of full spore heat resistance during Bacillus subtilis sporulation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77 6746–6754. 10.1128/AEM.05031-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A., Trentini D. B., Spiess S., Fuhrmann J., Ammerer G., Mechtler K., et al. (2014). Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals the role of protein arginine phosphorylation in the bacterial stress response. Mol. Cell Proteomics 13 537–550. 10.1074/mcp.M113.032292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciochetti S. A., Blakely G. W., Piggot P. J. (2001). Growth phase variation in cell and nucleoid morphology in a Bacillus subtilis recA mutant. J. Bacteriol. 183 2963–2968. 10.1128/JB.183.9.2963-2968.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev E., Smith Y., Ben-Yehuda S. (2012). RNA dynamics in aging bacterial spores. Cell 148 139–149. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P. (2003). Spore germination. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6 550–556. 10.1016/j.mib.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P. (2006). Spores of Bacillus subtilis: their resistance to and killing by radiation, heat and chemicals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101 514–525. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02736.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P. (2007). I will survive: DNA protection in bacterial spores. Trends Microbiol. 15 172–180. 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P. (2008). Dormant spores receive an unexpected wake-up call. Cell 135 410–412. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P. (2014). Germination of spores of Bacillus species: what we know and do not know. J. Bacteriol. 196 1297–1305. 10.1128/JB.01455-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafikhani S. H., Núñez E., Leighton T. (2004). Hpr (ScoC) and the phosphorelay couple cell cycle and sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231 99–110. 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00936-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah I. M., Dworkin J. (2010). Induction and regulation of a secreted peptidoglycan hydrolase by a membrane Ser/Thr kinase that detects muropeptides. Mol. Microbiol. 75 1232–1243. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah I. M., Laaberki M. H., Popham D. L., Dworkin J. (2008). A eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr kinase signals bacteria to exit dormancy in response to peptidoglycan fragments. Cell 135 486–496. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Pigeonneau N., Ravikumar V., Dobrinic P., Macek B., Franjevic D., et al. (2014a). Cross-phosphorylation of bacterial serine/threonine and tyrosine protein kinases on key regulatory residues. Front. Microbiol. 5:495 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Pigeonneau N., Ventroux M., Derouiche A., Bidnenko V., Mijakovic I., et al. (2014b). Protein-tyrosine phosphorylation interaction network in Bacillus subtilis reveals new substrates, kinase activators and kinase cross-talk. Front. Microbiol. 5:538 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinai L., Rosenberg A., Smith Y., Segev E., Ben-Yehuda S. (2015). The molecular timeline of a reviving bacterial spore. Mol. Cell 57 695–707. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soufi B., Kumar C., Gnad F., Mann M., Mijakovic I., Macek B. (2010). Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) applied to quantitative proteomics of Bacillus subtilis. J. Proteome Res. 9 3638–3646. 10.1021/pr100150w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squeglia F., Marchetti R., Ruggiero A., Lanzetta R., Marasco D., Dworkin J., et al. (2011). Chemical basis of peptidoglycan discrimination by PrkC, a key kinase involved in bacterial resuscitation from dormancy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 20676–20679. 10.1021/ja208080r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stragier P., Losick R. (1996). Molecular genetics of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 30 297–341. 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm A., Dworkin J. (2015). Phenotypic diversity as a mechanism to exit cellular dormancy. Curr. Biol. 25 2272–2277. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan I. S., Ramamurthi K. S. (2014). Spore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 6 212–225. 10.1111/1758-2229.12130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishnoi M., Narula J., Devi S. N., Dao H. A., Igoshin O. A., Fujita M. (2013). Triggering sporulation in Bacillus subtilis with artificial two-component systems reveals the importance of proper Spo0A activation dynamics. Mol. Microbiol. 90 181–194. 10.1111/mmi.12357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Zou W., Fang J., Huang X., Gao F., He Z., et al. (2015). Eukaryote-like Ser/Thr protein kinase PrkA modulates sporulation via regulating the transcriptional factor σ(K) in Bacillus subtilis. Front. Microbiol. 6:382 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeats C., Finn R. D., Bateman A. (2002). The PASTA domain: a beta-lactam-binding domain. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27:438 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02164-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilhão R., Isticato R., Martins L. O., Steil L., Völker U., Ricca E., et al. (2005). Assembly and function of a spore coat-associated transglutaminase of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 187 7753–7764. 10.1128/JB.187.22.7753-7764.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]