Abstract

Membrane proteins play crucial roles in signaling and as anchors for cell surface display. Proper secretion of a membrane protein can be evaluated by its susceptibility to digestion by an extracellular protease, but this requires a crucial control to confirm membrane integrity during digestion. This protocol describes how to use this approach to determine how efficiently a protein is secreted to the outer surface of Gram-negative bacteria. Its success relies upon careful selection of an appropriate intracellular reporter protein that will remain undigested if the membrane barrier remains intact, but is rapidly digested when cells are lysed prior to evaluation. Reporter proteins that are resistant to proteases (e.g. maltose-binding protein) do not return accurate results; in contrast, proteins that are more readily digested (e.g. SurA) serve as more sensitive reporters of membrane integrity, yielding more accurate measurements of membrane protein localization. Similar considerations apply when evaluating membrane protein localization in other contexts, including eukaryotic cells and organelle membranes. Evaluating membrane protein localization using this approach requires only standard biochemistry laboratory equipment for cell lysis, gel electrophoresis and western blotting. After expression of the protein of interest, this procedure can be completed in 4 h.

Introduction

Cell surface-associated membrane proteins represent a diverse superfamily of proteins that enable a cell to sense and interact with its environment. Moreover, several of these proteins have been adapted to display novel protein functions on the surface of Gram-negative bacteria for cellular engineering, in vitro evolution and biotechnological applications1,2. The structural and functional features of these proteins are therefore of intense interest. However, before beginning an in-depth characterization of a membrane-associated protein, it is first necessary to confirm its secretion to the cell surface, thereby ensuring its availability to bind substrate molecules and binding partners.

Extracellular protease digestion is routinely used as a quick and straightforward method to ascertain the successful integration and surface exposure of membrane-associated proteins in live cells3–17. The idea is that the protein of interest will be accessible to the protease if displayed at the cell surface, but resistant to protease digestion if trapped behind the membrane (Fig. 1a). Protease digestion is a particularly valuable approach for determining membrane protein localization when the protein of interest lacks an easily assayed enzymatic activity or binding partner. This assay is suitable for analyzing either overexpressed or naturally occurring proteins. It requires only antibodies specific for the protein of interest and an appropriate intracellular marker protein (described below), and standard laboratory equipment for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting. In contrast to many other methods to assess membrane protein localization, including immunosorbent assays of the accessibility of an epitope tag18 and microscopy approaches to visualize an added fluorescent protein domain15,16, testing membrane localization via protease digestion does not require covalent modification of the protein of interest, thereby reducing the complexity of the assay and avoiding potential effects of these covalent modifications on membrane localization and/or protein function. Indeed, protease digestion provides a convenient method to test to what extent, if any, the covalent modification of a membrane protein affects its localization.

Figure 1.

Accurate use of protease digestion to confirm protein cell surface display requires monitoring a protease-sensitive intracellular control protein. (a) When the membrane of interest (in this example, the bacterial outer membrane (OM)) remains intact, the protease (yellow) will only have access to and digest the protein of interest (green) when it is displayed on the extracellular side of the OM. Improperly secreted forms of the protein of interest will remain intact, along with any intracellular control proteins (blue and purple), regardless of their stability. (b) Higher protease concentrations or other stress, including too-vigorous cell resuspension, can destabilize cell membranes, enabling protease access to the intracellular marker proteins. This will lead to digestion of both extracellular and intracellular forms of the protein of interest, but can be detected by digestion of a protease-sensitive reporter protein (blue). However, if the selected reporter protein is highly resistant to degradation (purple), it will remain resistant to digestion regardless of membrane integrity, leading to the erroneous conclusion that the OM remains intact and all of the protein of interest resides at the cell surface.

Typically, membrane protein localization by protease digestion involves subjecting cells to digestion with a non-specific protease such as proteinase K (proK)4,5,10,14,17,19,20. Accurate interpretation of the results from this assay requires that the cell membrane(s) remain intact during protease digestion, blocking access to intracellular components (Fig. 1b). The resistance of a known intracellular reporter protein to protease digestion serves as important control for the integrity of the membrane. For testing successful secretion of proteins to the extracellular surface of E. coli, the periplasmic protein maltose binding protein (MBP) has often been used as this reporter4,10,19,20. However, to serve as an accurate reporter of membrane integrity, the protease resistance of the selected intracellular reporter protein must be low. If the reporter is highly resistant to degradation, it will remain intact even when the integrity of the OM has been compromised, enabling the protease to gain access to the other side of the membrane where it can digest improperly localized forms of the protein of interest and lead to inaccurate conclusions regarding its localization (Fig. 1b). This scenario is of particular concern when other aspects of the experimental design predispose cell membrane(s) towards destabilization, including cell envelope instability caused by addition of beta-lactam antibiotics21 in order to maintain an expression plasmid bearing AmpR. A simple – but surprisingly often overlooked – positive control experiment, to ensure that the reporter protein is rapidly degraded after intentional membrane disruption, is required in order to determine under what digestion conditions the selected marker protein provides accurate information on membrane integrity.

Here we provide a detailed protocol for determining extracellular localization of a membrane protein of interest, including the selection and testing of an appropriate intracellular reporter protein. We show that although E. coli MBP has often been used as a reporter for the integrity of the bacterial OM during extracellular protease digestion, it is highly resistant to digestion by both proteinase K and trypsin, a common protease used in proteomics and other mass spectrometry approaches. Hence using MBP as an intracellular marker protein can lead to inaccurate conclusions regarding OM membrane integrity. However, other less stable periplasmic proteins, including SurA, more accurately report on the integrity of the OM and therefore lead to more accurate conclusions regarding membrane localization of the protein of interest.

A simple positive control experiment, where cells are lysed prior to protease digestion, can determine whether a selected intracellular protein is suitably protease-sensitive for use as a marker protein. Although including this control experiment might appear obvious it is nevertheless missing from a significant fraction of published studies, leading some subsequent studies, which likely developed protocols based upon earlier published accounts, to inadvertently perpetuate this omission. Selection of an intracellular marker protein that is more protease-sensitive than the membrane protein of interest is a universal requirement for accurate interpretation of protease-accessibility assays. Hence the general strategy described here, including the control experiments to evaluate the protease susceptibility of the selected intracellular reporter protein, also applies to membrane localization studies in other systems, including eukaryotic cells and organelles.

It is important to note that even when carefully controlled this assay cannot provide precise structural information on the integration of a protein into the membrane (single- versus multi-spanning versus lipid-anchored, positions of the amino- and carboxyl termini with respect to the membrane, etc.). However, an accurate assessment of the display of the membrane protein on the proper face of a cell membrane is an essential prerequisite before launching a more precise structural analysis, which might include using an epitope-mapped panel of monoclonal antibodies or other approaches3 to identify surface-exposed portions of the membrane protein. Proper selection of an intracellular marker protein to ensure membrane integrity during protease digestion is also an essential component of mass spectrometry approaches to accurately identify the sub-proteome of naturally occurring cell surface proteins22,23.

Materials

Reagents

E. coli expression plasmid vector pET21b (EMD Millipore, cat. no. 69741-3), or other suitable expression plasmid, subcloned with coding sequence for protein of interest

E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS (EMD Millipore, cat. no. 70236) or other expression strain transformed with expression plasmid above

LB broth medium (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. L3022)

LB broth with agar (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. L3147)

Ampicillin (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A9518), or other appropriate antibiotic

Isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 15502)

Tris Base (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. RDD008)

Tris HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. RDD009)

Calcium chloride, anhydrous (Fisher Scientific, cat. No. C614-500)

Proteinase K (Promega, cat. no. V3021)

Trypsin (Promega, cat. no. V5111)

-

0.1M Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) in ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 93482)

#CAUTION Ethanol is flammable. PMSF is toxic if swallowed, and causes severe skin burns and eye damage. Wear gloves and chemical safety goggles while handling.

4–20% gradient precast polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 456–1091), or other polyacrylamide gels capable of resolving the protein of interest and the intracellular control protein

Trans-Blot Turbo Nitrocellulose Transfer Kit (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 170-4270)

Glycine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. G8898)

Glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. G5516)

Bromophenol blue (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. B0126)

Dithiothreitol (DTT) (Fisher Scientific, cat no. R0861)

Powdered dry milk (PDM) (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. M7409)

Primary antibodies specific for the protein of interest and the intracellular marker protein. We illustrate the protocol using rabbit anti-YapV and mouse anti-SurA polyclonal antibodies described previously8,24.

Appropriate enzyme-conjugated secondary antibodies. The application described here used an alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Novus Biologicals, cat. no. NB7157) and AP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Southern Biotech, cat. No.1030-04).

Color development substrates for AP (nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-phosphate (BCIP)) (Promega, cat. no. S3771)

Equipment

125 ml and 250 ml sterile glass culture flasks (VWR, cat. no. 71000-404 and 71000-424)

50 ml sterile polypropylene centrifuge tubes (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 05-539-6)

1.5 ml sterile microcentrifuge tubes (USA Scientific, cat. no. 1615-5510)

Shaking incubator with temperature control (New Brunswick Innova 44 or equivalent)

Low speed tabletop centrifuge that can accommodate the 50 ml polypropylene tubes described above (Beckman Coulter Allegra 6R or equivalent)

Microcentrifuge with variable speed settings (Eppendorf 5415C or equivalent)

Sonicator (QSonica Misonix Q125 or equivalent) or other cell lysis method, including Glen Mills model 11 French press or Avestin C5 Homogenizer

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis equipment

Heating block, set at 100°C

Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 170-4155)

Reagent Setup

Overnight bacterial culture Select a single colony from an LB-agar plate supplemented with 50 μg/ml ampicillin (or other appropriate antibiotic) and use it to inoculate 20 ml LB medium in a 125 ml culture flask supplemented with the same concentration of appropriate antibiotic. Incubate overnight with shaking (200 rpm) at 37°C.

1 M Tris pH 8.8 Combine 170 ml 1 M Tris-HCl (157.56 g Tris-HCl in 1L water) plus 830 ml 1 M Tris Base (121.14 g in 1L water). This buffer can be stored at room temperature (RT) for at least 1 year. RT in our laboratory is 23°C.

Protease buffer 50 mM Tris 7.5 mM Cacl2 pH 8.8. This buffer can be stored at RT for at least 1 year.

Protease stock solutions Dissolve either Proteinase K (2 mg/ml) or Trypsin (4 mg/ml) in protease buffer. Dilute 1:1 with glycerol, and store single-use aliquots at -20°C for at least 1 year.

2X SDS loading buffer Combine 100 mM Tris pH 6.8, 4% (w/v) SDS, 0.2% (w/v) bromophenol blue, 20% (v/v) glycerol and 200 mM DTT. Add DTT shortly before use. The remaining components of this buffer can be stored as single-use aliquots at -20°C for at least 1 year.

Tris-buffered saline Tween-20 (TBST) buffer Combine 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 0.5% (v/v) Tween-20. This buffer can be stored at RT for at least one year.

5% and 2% PDM in TBST buffer Add 5% (w/v) or 2% (w/v) PDM to the TBST buffer described above. Make fresh each time.

AP buffer Combine 100 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 pH 9.5. This portion of the buffer can be stored at RT for at least 1 year. Shortly before use, add 66 μl NBT and 35 μl BCIP to 10 ml AP buffer.

Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer Buffer Make according to manufacturer’s directions. Store at 4°C for at least 1 year.

Procedure

E. coli growth and protein expression

#TIMING 2 h for cell growth, 1.5 h for protein expression and centrifugation

-

1

Use 2 ml of the overnight culture to inoculate 100 ml of fresh LB medium in a 250 ml culture flask supplemented with 50 μg/ml ampicillin (or other appropriate antibiotic). Incubate with shaking (200 rpm) at 37°C until the culture attains A600 = 0.5 (approximately 2 h).

-

2

Induce expression by adding 100 3l 1M isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.5 mM IPTG. Continue shaking at 37°C for an additional hour.

-

3

Divide culture between two 50 ml centrifuge tubes and harvest cells by centrifugation at 1,500xg for 10 min. Decant supernatant.

#CRITICAL STEP Do not use high speed centrifugation, as this can lead to premature cell lysis.

Protease digestion of intact cells and cell lysates

#TIMING 1 h

-

4

To each tube, add 10 ml protease buffer. Resuspend cells by gently rocking the centrifuge tube.

#CRITICAL STEP Gentle rocking is required. More vigorous methods to resuspend the cells, including repeated pipetting, can lead to premature lysis.

-

5

For one tube, sonicate on ice for three cycles of 30 seconds on /30 seconds off. Other lysis strategies, including a French press or the Avestin C5 Homogenizer, can be used in place of sonication.

#CRITICAL STEP Sonication must be performed on ice, to prevent thermal denaturation of proteins. Avoid prolonged sonication, which can lead to sample heating.

#CRITICAL STEP The cell lysis control must be performed each time, to control for batch-to-batch and supplier-to-supplier differences in protease specific activity.

-

6

Aliquot 270 3l of the resuspended cells into each of four microcentrifuge tubes, labelled proK 0, proK 10, proK 25 and proK 100 (corresponding to 0, 10, 25 and 100 3g/ml proteinase K). Repeat for the lysed cells.

-

7

Aliquot 270 3l of the resuspended cells into each of four microcentrifuge tubes labeled Tryp 0, Tryp 20, Tryp 50 and Tryp 200 (corresponding to 0, 20, 50 and 200 3g/ml trypsin). Repeat for the lysed cells.

-

8

For proK digestions, add 30 3l protease buffer only, 27 3l buffer + 3 3l proK stock solution, 22.5 3l buffer + 7.5 3l proK stock solution or 30 3l proK stock solution to the proK 0, proK 10, proK 25 and proK 100 tubes, respectively.

-

9

For trypsin digestions, add 30 3l protease buffer only, 27 3l buffer + 3 3l trypsin stock solution, 22.5 3l buffer + 7.5 3l trypsin stock solution or 30 3l trypsin stock solution to the Tryp 0, Tryp 20, Tryp 50 and Tryp 200 tubes, respectively.

-

10

Incubate for 30 min at room temperature with gentle mixing every 5 min, then add 20 3l of 0.1 M PMSF and mix gently. Incubate for an additional 5-10 min.

#CRITICAL STEP The protease must be completely inactivated with PMSF before proceeding to SDS-PAGE. Proteinase K remains active up to 70°C and in 2% SDS, conditions that can destabilize membranes and therefore grant remaining active protease access to intracellular proteins. Moreover, as cellular proteins are denatured by heating and incubation in SDS they will become more susceptible to protease digestion, complicating the interpretation of results.

-

11

For tubes with intact cells, centrifuge at 1,500xg for 10 min. Discard the supernatant, add 300 3l of 50 mM Tris pH 8.8 and resuspend cell pellet.

#PAUSE POINT Samples can be stored indefinitely at −20°C, or proceed directly to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis

#TIMING 2.5 h

-

12

Aliquot 100 3l of each sample into a fresh tube. Add 100 3l of 2X SDS loading buffer and boil at 100°C for 10 min.

-

13

Load a portion of each sample onto two 4-20% gradient precast polyacrylamide gels and run at 175 V for 45 min. One gel will be used to detect the protein of interest; the other will be used to detect the intracellular marker protein. Load a third gel in order to compare performance of a second intracellular marker, as shown in Fig. 2.

-

14

Assemble blot transfer “sandwiches”, consisting of each gel plus a nitrocellulose membrane, following manufacturer directions provided for the Trans-Blot Turbo Nitrocellulose Transfer Kit and the Trans-Blot Transfer system. Alternatively, other western blot transfer systems can be used, although the blotting procedure may take longer.

-

15

Incubate membranes in 5% PDM in TBST buffer for 10-20 min.

-

16

Prepare 20 ml of each primary antibody in 2% PDM in TBST buffer at an appropriate dilution for western blotting. Incubate each membrane in its respective primary antibody solution for 45 min, with gentle rocking at room temperature.

-

17

Wash each membrane three times with ~30 ml TBST buffer (3–5 min per wash).

#CRITICAL STEP Make sure membranes are thoroughly washed to remove all unbound primary antibodies.

-

18

Prepare 20 ml of an appropriate secondary antibody in 2% PDM in TBST buffer at a concentration appropriate for western blotting (1:20,000 dilution of the AP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and AP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG used here). Alternatively, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (and appropriate detection reagents) can be used.

-

19

Incubate each membrane in its respective secondary antibody solution for 30 min, with gentle rocking at room temperature.

-

20

Wash each membrane three times with ~30 ml TBST buffer (3-5 min per wash).

#CRITICAL STEP Make sure membranes are thoroughly washed to remove all unbound secondary antibodies.

-

21

Develop blot by incubating membrane with AP buffer with NBT and BCIP added.

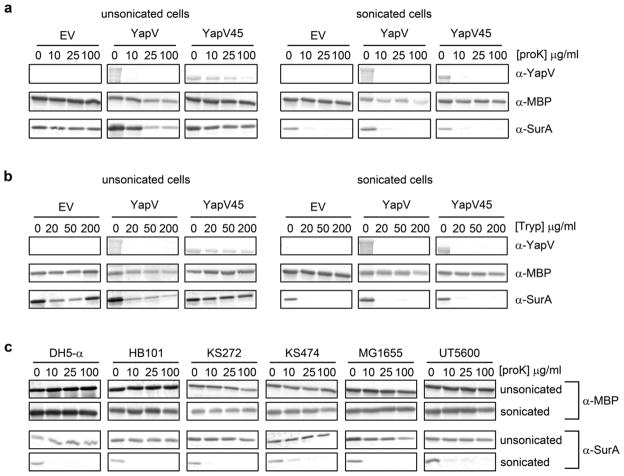

Figure 2.

Western blots showing the resistance of YapV45, MBP and SurA to digestion by proteinase K (proK) or trypsin (Tryp) in intact cells or sonicated cell lysates. (a) Proteinase K treatment of E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS expressing YapV, YapV45 or harboring the empty vector (EV). YapV is digested on the surface of intact cells. When cells are lysed by sonication prior to proK treatment, the cytoplasm localized YapV45 and the periplasmic chaperone SurA are digested, but the periplasmic MBP is not digested. (b) Trypsin treatment results in the same digestion pattern as proK. (c) Proteinase K treatment of several additional strains of E. coli. MBP is resistant to digestion by proK in all strains tested, even after cell lysis by sonication prior to proK treatment. In contrast, SurA remains undigested after proK treatment of intact cells, but is digested by proK when cells are lysed by sonication prior to proK treatment.

Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Reason | Possible solution |

|---|---|---|

| Intracellular marker not degraded after cell lysis |

|

|

| Intracellular marker degraded in intact cell samples |

|

|

| Inconsistent degradation of the protein of interest and/or intracellular marker |

|

|

Timing

Steps 1–3, E. coli growth and protein expression: ~4 h

Steps 4–11, Proteinase K and trypsin digestion of intact cells and cell lysates: ~1 h

Steps 12–21, SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis, ~3 h

Anticipated Results

To illustrate the complications that can arise when a protease-resistant versus protease-sensitive protein is used as an intracellular marker, we provide here a case study using the intracellular marker proteins MBP and SurA to analyze the proper secretion of the Y. pestis autotransporter protein YapV to the outer surface of E. coli. Similar considerations will apply to the selection of an appropriate intracellular marker protein in other organisms, including yeast, plants and mammalian cells and organelles.

We treated E. coli expressing the Y. pestis autotransporter YapV8 with proK up to 100 3g/ml or trypsin up to 200 3g/ml, concentrations well within those used in published studies. These treatments resulted in digestion of full-length YapV, while the periplasmic reporter protein MBP remained intact (Fig. 2a and b). The standard conclusion from this result would be that YapV is exposed on the cell surface. However, we observed that MBP remained insensitive to protease digestion even when E. coli were lysed by sonication prior to protease treatment (Fig. 2a and b). Hence from the MBP control alone it would be impossible to determine whether YapV is located at the cell surface or within the periplasm (Fig. 1b). Indeed, digestion of intact E. coli with 100 3g/ml proK also resulted in significant digestion of YapV45, a truncated, secretion-incompetent version of YapV that remains within the cytoplasm8, indicating that treatment with 100 3g/ml proK led to permeablization of both the OM and the bacterial inner membrane (IM), despite leaving MBP unaffected (Fig. 2a). We found that MBP remained insensitive to digestion even at higher protease concentrations (up to 400 3g/ml proK, used in some published studies), even though the cytoplasm-localized YapV45 was completely digested under these conditions (Fig. 3). These results underscore the crucial importance of analyzing the degradation of the selected marker protein in lysed cells as a positive control for loss of membrane integrity.

Figure 3.

MBP is resistant to proK digestion even at high (400 μg/ml) proK concentrations. E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS expressing the indicated constructs were treated with proK at the indicated concentrations. For intact cells treated with 400 μg/ml proK, the cytoplasm-localized YapV45 is completely digested even though the periplasm-localized MBP remains largely intact.

To test whether the resistance of MBP to protease digestion was specific to E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS, we repeated this analysis using six additional E. coli strains (DH5α, HB101, KS272, KS474, MG1655 and UT5600). For each strain, there was no significant digestion of MBP even when cells were lysed by sonication prior to proK treatment (Fig. 2c). These results underscore the unsuitability of MBP as a marker for OM integrity for assays involving protease treatment of intact cells.

In contrast, other intracellular proteins that are more susceptible to protease digestion are better suited to report on the integrity of the OM. Using the same approach as described above for MBP, we found that the periplasmic chaperone SurA was protected from protease digestion within intact cells (Fig. 2), but unlike MBP, SurA was completely digested at even the lowest protease concentrations when cells were lysed by sonication prior to protease treatment. Hence because it is more susceptible to protease degradation, the periplasmic protein SurA can serve as a more sensitive and accurate reporter of OM integrity.

Interestingly, for cells expressing surface-exposed YapV, SurA was partially digested after treatment with proK or trypsin at concentrations greater than 10 3g/ml (Fig. 2a and b). This partial digestion of SurA was not observed for cells expressing the empty vector or the cytoplasm-localized construct YapV45, indicating that expression of the outer membrane-tethered YapV renders the OM more susceptible to destabilization upon protease treatment. However, reducing the proK concentration to 10 3g/ml led to digestion of only the surface exposed YapV, leaving SurA intact (Fig. 2a).

These results demonstrate the importance of selecting a protease-sensitive protein as an intracellular reporter during digestions of intact cells. For example, proK concentrations of 100 3g/ml and higher led to the digestion of an unstable protein localized within the cytoplasm (YapV45, Fig. 2a), an effect that would have gone unnoticed had we simply checked for digestion of MBP or SurA, both of which are more resistant to protease digestion. Most importantly, when testing for surface display of a protein on live cells it is imperative to confirm the integrity of the cell membrane(s) after protease digestion by demonstrating that the selected intracellular reporter protein does indeed become susceptible to protease digestion when cell membranes are intentionally disrupted prior to protease treatment. This consideration applies regardless of the cell type and/or membrane protein being analyzed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Luis Angel Fernandez (Centro Nacional de Biotecnologia, Madrid, Spain), Carol Gross (University of California San Francisco) and Jonathan Beckwith (Harvard Medical School) for providing strains UT5600, MG1655, and KS272 and KS474, respectively, and David Hunstad (Washington University St. Louis) for the anti-SurA antibody. This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM097573).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

R.N.B. and P.L.C. developed the concept, designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. R.N.B. carried out the experimental work, analyzed the data and prepared Figures 2 and 3. P.L.C. prepared Figure 1.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Jose J, Maas RM, Teese MG. Autodisplay of enzymes--molecular basis and perspectives. J Biotechnol. 2012;161:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jong W, et al. An autotransporter display platform for the development of multivalent recombinant bacterial vector vaccines. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13:162. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Junker M, Besingi RN, Clark PL. Vectorial transport and folding of an autotransporter virulence protein during outer membrane secretion. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1323–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenz JD, et al. Expression during host infection and localization of Yersinia pestis autotransporter proteins. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:5936–49. doi: 10.1128/JB.05877-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sauri A, et al. Autotransporter beta-domains have a specific function in protein secretion beyond outer-membrane targeting. J Mol Biol. 2011;412:553–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauri A, Ten Hagen-Jongman CM, van Ulsen P, Luirink J. Estimating the size of the active translocation pore of an autotransporter. J Mol Biol. 2012;416:335–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selkrig J, et al. Discovery of an archetypal protein transport system in bacterial outer membranes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:506–10. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Besingi RN, Chaney JL, Clark PL. An alternative outer membrane secretion mechanism for an autotransporter protein lacking a C-terminal stable core. Mol Microbiol. 2013;90:1028–45. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benoit VM, Fischer JR, Lin YP, Parveen N, Leong JM. Allelic variation of the Lyme disease spirochete adhesin DbpA influences spirochetal binding to decorin, dermatan sulfate, and mammalian cells. Infect Immun. 2011;79:3501–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00163-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noinaj N, et al. Structural insight into the biogenesis of beta-barrel membrane proteins. Nature. 2013;501:385–90. doi: 10.1038/nature12521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hao G, Boyle M, Zhou L, Duan Y. The intracellular citrus huanglongbing bacterium, 'Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus' encodes two novel autotransporters. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yim SS, An SJ, Han MJ, Choi JW, Jeong KJ. Isolation of a potential anchoring motif based on proteome analysis of Escherichia coli and its use for cell surface display. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;170:787–804. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu R, et al. Development of a whole-cell biocatalyst/biosensor by display of multiple heterologous proteins on the Escherichia coli cell surface for the detoxification and detection of organophosphates. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:7810–6. doi: 10.1021/jf402999b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schumacher SD, Jose J. Expression of active human P450 3A4 on the cell surface of Escherichia coli by Autodisplay. J Biotechnol. 2012;161:113–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorenz H, Hailey DW, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Fluorescence protease protection of GFP chimeras to reveal protein topology and subcellular localization. Nat Methods. 2006;3:205–10. doi: 10.1038/nmeth857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenz H, Hailey DW, Wunder C, Lippincott-Schwartz J. The fluorescence protease protection (FPP) assay to determine protein localization and membrane topology. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:276–9. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang'ethe W, Bernstein HD. Stepwise folding of an autotransporter passenger domain is not essential for its secretion. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:35028–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.515635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naganathan S, Ye S, Sakmar TP, Huber T. Site-specific epitope tagging of G protein-coupled receptors by bioorthogonal modification of a genetically encoded unnatural amino acid. Biochemistry. 2013;52:1028–36. doi: 10.1021/bi301292h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigel NW, Ricci DP, Silhavy TJ. Conformation-specific labeling of BamA and suppressor analysis suggest a cyclic mechanism for beta-barrel assembly in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5151–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302662110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigel NW, Schwalm J, Ricci DP, Silhavy TJ. BamE modulates the Escherichia coli beta-barrel assembly machine component BamA. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:1002–8. doi: 10.1128/JB.06426-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comeau AM, Tetart F, Trojet SN, Prere MF, Krisch HM. Phage-Antibiotic Synergy (PAS): beta-lactam and quinolone antibiotics stimulate virulent phage growth. PLoS One. 2007;2:e799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy GM, Hooley GC, Champion MM, Mba Medie F, Champion PA. A novel ESX-1 locus reveals that surface-associated ESX-1 substrates mediate virulence in Mycobacterium marinum. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:1877–88. doi: 10.1128/JB.01502-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olaya-Abril A, Jimenez-Munguia I, Gomez-Gascon L, Rodriguez-Ortega MJ. Surfomics: shaving live organisms for a fast proteomic identification of surface proteins. J Proteomics. 2014;97:164–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watts KM, Hunstad DA. Components of SurA required for outer membrane biogenesis in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]