Abstract

The aims of this mixed-method pilot study were to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary psychosocial outcomes of “Making Friends with Yourself: A Mindful Self-Compassion Program for Teens” (MFY), an adaptation of the adult Mindful Self-Compassion program. Thirty-four students age 14–17 enrolled in this waitlist controlled crossover study. Participants were randomized to either the waitlist or intervention group and administered online surveys at baseline, after the first cohort participated in the intervention, and after the waitlist crossovers participated in the intervention. Attendance and retention data were collected to determine feasibility, and audiorecordings of the 6-week class were analyzed to determine acceptability of the program. Findings indicated that MFY is a feasible and acceptable program for adolescents. Compared to the waitlist control, the intervention group had significantly greater self-compassion and life satisfaction and significantly lower depression than the waitlist control, with trends for greater mindfulness, greater social connectedness and lower anxiety. When waitlist crossovers results were combined with that of the first intervention group, findings indicated significantly greater mindfulness and self-compassion, and significantly less anxiety, depression, perceived stress and negative affect post-intervention. Additionally, regression results demonstrated that self-compassion and mindfulness predicted decreases in anxiety, depression, perceived stress, and increases in life satisfaction post-intervention. MFY shows promise as a program to increase psychosocial wellbeing in adolescents through increasing mindfulness and self-compassion. Further testing is needed to substantiate the findings.

Keywords: adolescents, mindfulness, self-compassion, teens, emotional wellbeing

Introduction

Adolescence is a vulnerable period of growth and challenge, characterized by rapid cognitive, physiological and neurological changes (Giedd, 2008; Susman & Dorn, 2009). Adolescents are confronted daily with emotional and interpersonal challenges that accompany these developmental changes. A developing self-identity and peer pressure to “fit in” lead to elevated stress and negative self-evaluation (Neff & McGehee, 2010). Without appropriate coping skills to manage these challenges, adolescents are more vulnerable for depression and other psychological disorders (Horwitz, Hill, & King, 2011). These negative events may precipitate further maladaptive behaviors such as substance abuse, poor school attendance, and violence against themselves or others, which increase a risk for a downward life trajectory (Albano, Chorpita, & Barlow, 2003; Crocetti, Klimstra, Keijsers, Hale, & Meeus, 2009). Adolescent-appropriate interventions that provide coping skills may help adolescents to successfully navigate the challenges confronted during adolescence and set individuals on a healthy path for life.

One such potential intervention is a mindful self-compassion program, which combines the complementary benefits of mindfulness and self-compassion. Mindfulness is the ability to pay attention, on purpose, in the present moment, with non-judgment and acceptance (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). It includes recognition of thoughts or emotions that are in one’s momentary experience, then subsequently letting them go of them, recognizing them as transitory (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002). Self-compassion, as defined by Neff (2003), includes three components: mindfulness, described as being open and present to one’s own suffering; self-kindness, described as responding with soothing and loving care to oneself at times of suffering; and common humanity, described as recognizing that suffering is inherent in the human experience. Research on self-compassion has provided evidence for its association with beneficial mental health outcomes and potential for promoting emotional resilience. For example, a meta-analysis of self-compassion in adults indicated a large effect size for its association with lower psychopathology (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012). Although most of the current research has been limited to cross-sectional studies, longitudinal research with adults indicates that self-compassion predicts lower depression symptomatology over a 5-month period (Raes, 2011). In adolescents, greater self-compassion is associated with lower depression, anxiety, and stress and greater well-being and self-esteem (Barry, Loflin, & Doucette, 2015; Bluth & Blanton, 2014a, 2014b; Neff & McGehee, 2010). Additionally, among high-school students, self-compassion is associated with a sense of community (Akin & Akin, 2014), and protects against the negative effects of low self-esteem when assessed over a one year interval (Marshall et al., 2015). Finally, self-compassion appears to have a protective effect in adolescent populations that are at risk for poor mental health outcomes. Among adolescents who experienced childhood maltreatment, those with lower self-compassion were more likely to experience greater psychological distress, alcohol abuse, and were more likely to report a suicide attempt (Tanaka, Wekerle, Schmuck, & Pagila-Boak, 2011). Among adolescents exposed to a potentially traumatic stressful event (the Mount Carmel Forest Fire Disaster), self-compassion exerted a protective effect, beyond dispositional mindfulness, with respect to post-traumatic stress, panic, depressive, and suicidality symptoms at 3 and 6 months after the traumatic event (Zeller, Yuval, Nitzan-Assayag, & Bernstein, 2014). As noted, many of these findings are based on correlational or cross-sectional studies. It would be of further importance to develop and test a self-compassion intervention for adolescents that may promote positive mental health outcomes and emotional resilience to protect against the challenges of adolescence.

Mindfulness interventions have been developed for adolescents and are associated with decreased stress and increased life satisfaction, positive affect, happiness, and overall well-being (e.g., Biegel, Brown, Shapiro, & Schubert, 2009; Broderick & Metz, 2009; Brown, West, Loverich, & Biegel, 2011; Schonert-Reichl & Lawlor, 2010). However, these interventions tend to focus on the qualities of attention, awareness, non-judgment, and acceptance (mindfulness), with only minor consideration given to actively soothing one’s suffering or recognition of the universality of these experiences (self-compassion). Neff and Germer (2013) have recently developed an 8-week Mindful Self-Compassion program for adults that focuses on cultivating self-compassion. Clinical trial data from this program have demonstrated decreases in anxiety, depression, and stress, and increases in life satisfaction, social connectedness, compassion for others, and happiness (Neff & Germer, 2013). Additionally, a modified 3-week version of this program resulted in decreases in rumination and increases in optimism and self-efficacy among female college students (Smeets, Neff, Alberts, & Peters, 2014). Although adolescents have the potential to significantly benefit from self-compassion’s effects (Neff, 2003), there have been no self-compassion programs designed to fit the emotional and developmental needs, challenges, and interests of adolescents.

The primary goal of the present study was to test the feasibility and acceptability of a prototype Mindful Self-Compassion program, “Making Friends with Yourself” (MFY), which was adapted from the Mindful Self-Compassion program for adults (Neff & Germer, 2013). Our Mindful Self-Compassion Program for adolescents teaches the mindful self-compassion components of mindfulness, self-kindness, and awareness of common humanity in an age-appropriate fashion. Another aim was to identify relevant psychosocial outcomes associated with the intervention in young men and women aged 14–17. We hypothesized that the “Making Friends with Yourself” mindful self-compassion intervention would be feasible and acceptable to adolescents. Additionally, compared to a waitlist control, adolescents assigned to the program would have lower symptoms of depression, anxiety, negative affect and perceived stress, and higher life satisfaction, positive affect, and social connectedness after completing the program. Finally, we hypothesized that mindfulness and self-compassion would independently predict changes in psychosocial outcome measures.

Method

Participants

Enrolled participants included 34 adolescents (ages14 to17) who responded to flyers posted at their local high schools and in the community, and to emails that were sent out via university listservs. Seventy-four percent (n=26) of the participants were female and the distribution for race was: White 79% (n=27), African American 9% (n=3), Asian 6% (n=2), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander 3% (n=1), and other race 3% (n=1). Overall, the adolescents came from well-educated families; 55% (n=19) of mothers and 46% (n=16) of fathers had masters, doctorate, or professional degrees. In order to be eligible for the study, participants had to score < 13 on a modified Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale (KADS; LeBlanc, Almudevar, Brooks, & Kutcher, 2002) and not endorse the item which asked “Over the last week, how have you been ‘on average’ or ‘usually’ regarding thoughts, actions, of suicide?” Five adolescents were excluded from the study for this reason prior to enrollment and were referred to the study psychologist.

Procedure

Study design

This study utilized a mixed methods embedded design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). This type of design embeds qualitative data into an intervention design. The qualitative data were used to assess whether the program was acceptable to participants. Therefore, the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention in an adolescent population is investigated through both quantitative and qualitative data. The program’s effects on psychosocial outcomes are investigated through quantitative data.

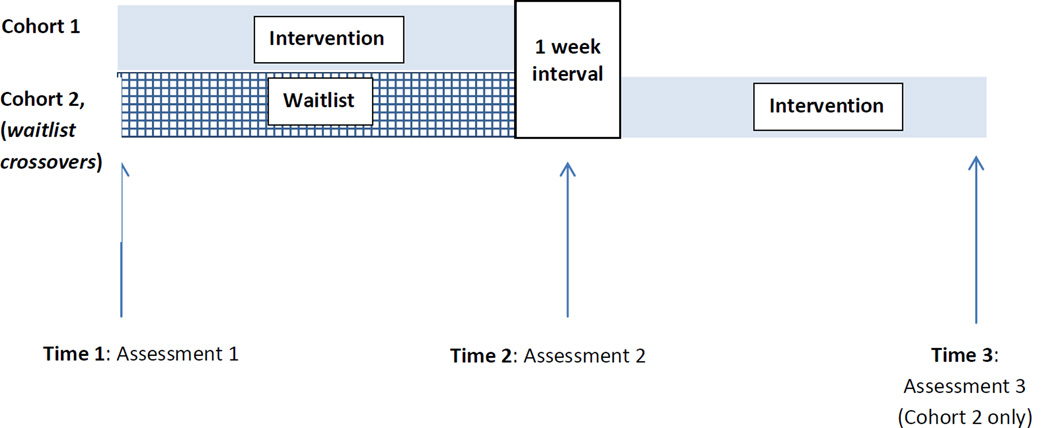

After the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, participants were recruited through the Program on Integrative Medicine’s listserv, a university-wide recruitment email service, and flyers that were posted at local high schools and in the community. Study screening phone interviews were scheduled with both the parent and adolescent. During this interview, the study coordinator explained the study, consent procedure, and eligibility requirements to first the parent and then the adolescent. Next, the adolescent completed a modified version of the KADS, which separated the suicide/self-harm item into two separate items for self-harm and for suicide. The adolescent was considered eligible if he/she scored below 13 on the KADS and did not endorse the suicide item. The parent and adolescent were emailed the consent and assent forms. Upon returning the consent forms, the adolescents were randomized into two groups: a treatment group (Cohort 1) or a waitlist control (Cohort 2), but not informed about their group placement until after they completed the baseline survey. The treatment group (Cohort 1) participated in the 6-week mindfulness and self-compassion adolescent program, “Making Friends with Yourself” (MFY), from February to March 2014 and the waitlist crossover group (Cohort 2) participated in the program from April to May 2014. Four days prior to Cohort 1’s first class (Time 1; see Fig. 1), all study participants were emailed a link to the online baseline survey. The survey was emailed a second time to all study participants the day following Cohort 1’s final class (Time 2). One week following, Cohort 2 began the six-week MFY program. The day following Cohort 2’s final class, Cohort 2 participants were again sent the link to the online survey (Time 3). Adolescents received a $25 gift card for completing each of the three surveys and attending 4 out of 6 of the class sessions, for a maximum total of $75.

Figure 1.

Depiction of the study time frame.

Intervention

“Making Friends With Yourself: A Mindful Self-compassion Program for Teens” (MFY) was a 6-week course that met weekly for 90 minutes. It was led by the first author (K. Bluth), a mindfulness practitioner for over 35 years, a mindfulness instructor for 3 years, and a certified teacher with 18 years classroom experience, 10 of which had been with adolescents.

Similar to the adult program (Neff & Germer, 2013), each weekly session of MFY had a specific theme. Session one provided an overview of the program, definition of mindfulness and self-compassion, and included several hands-on activities that encouraged participants’ self-discovery of mindfulness and self-compassion. For example, one exercise included a role-play which elucidated a key understanding of how we relate to ourselves and set the groundwork for self-compassion practice. Session two focused on mindfulness, and introduced several traditional practices including mindful breathing and bringing attention and awareness to physical sensations. Session three centered on the teenage brain, and included a didactic presentation of how two brain systems (cognitive control system and incentive processing system) are developing at different rates during adolescence. The cognitive control system includes the development of the prefrontal cortex (i.e., logical thinking, decision making) and the incentive processing system includes development of the amygdala and limbic system (i.e., fight-flight response). Discussion was encouraged related to the ramifications of these changes in the individual’s temperament, behavior, and family processes. Session four focused on describing how self-compassion is different than self-esteem, and articulated why self-compassion is a healthier way of relating to oneself. In this session, several short videos were shown that illustrated the differences between these two constructs. In Session five, participants were led through an exercise to find their inner “compassionate voice” and expressed it through their choice of a writing or art activity. The last session focused on gratitude, adolescents’ core values, and discussion of the overall program. In general, this program differed from the adult program in that classes were shorter, developmentally appropriate (e.g., more activity-based, incorporated a mindful movement segment halfway through each class, shorter guided meditations), and included a component about the adolescent brain.

In addition to the hands-on activities and exercises that elucidated the weekly theme, adolescents were introduced to specific formal and informal mindfulness and self-compassion practices. For example, in a formal practice, adolescents were led through a self-compassion body scan in which they were invited to bring warmth and affection to each part of their body while noticing sensations in that area of the body. In an informal practice called “A Moment for Me”, adolescents were taught to apply a soothing touch (e.g., stroking one’s arm, holding hands together) while repeating phrases that reminded them to do three things: 1) acknowledge their suffering in the moment that it is occurring, 2) recognize that emotional suffering is universal and part of the being human, and 3) actively soothe themselves precisely in these challenging moments by repeating kind phrases for themselves. In the last class, students were asked for feedback about the program. Specifically, they were asked about practices or meditations that they preferred and ones that they did not like. They were also asked about any suggestions that they might have for improving the program.

For homework, participants were assigned at least one formal and one informal mindfulness or self-compassion practice (e.g. formal guided meditation practice and informal “A Moment for Me” practice) to do during the week between classes. To support home practice, students were encouraged to access a website which had audio and video recordings of the adult versions of the class’s guided meditations, since a website with adolescent versions of the guided meditations was not available. These audio and video recordings were consistent with the practices that had been introduced in class. Prior to the beginning of class each week, students completed a questionnaire that assessed the number of days that week they engaged in any kind (both formal and informal) of mindfulness or self-compassion practice.

Measures

Feasibility and acceptability

Feasibility was assessed through attendance and retention data. A criteria of 75% attendance and 80% retention was established as a measure of feasibility; this is in accordance with previous studies (e.g., Sibinga et al., 2008, Mendelson et al., 2010). Acceptability was assessed through qualitative data which elucidated the degree to which participants were engaged in the content of the program, and participants’ feedback on the various program activities. Last, since this was a pilot study to evaluate a new intervention, participants were asked in the last class for oral feedback regarding the program.

Qualitative data collection

All classes were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The purpose of this was to inform our understanding of the kinds of mindful self-compassion meditations and other activities that are successful and acceptable to adolescents. Since this study is the first implementation of a mindful self-compassion program for adolescents of which we are aware, hearing the opinions, suggestions, and feedback of the participants in their own voices provides a rich source of descriptive data to inform refinement and future implementation of this program.

The online survey was administered at baseline and post-intervention within 24 hours of completing the last class. The survey included the following measures:

Mindfulness

The Children and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM; Greco, Baer, & Smith, 2011) assesses moment-to-moment attention and acceptance of internal experiences. Participants indicate their responses to each item using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never true) to 4 (always true). The total score is calculated by reverse scoring all items and then summing the items. The potential range of total scores is 0–40, with higher scores indicating greater mindfulness. Examples of items on this scale include: I get upset with myself for having certain thoughts and I push away thoughts that I don’t like. Factor analysis of the construction of this 10-item scale resulted in a one factor solution with a reported Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 (Greco et al., 2011). Reliability for this study is α = .76.

Positive and negative affect

To measure the extent to which individuals experienced positive and negative affect over the past week, the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule was used (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The PANAS is comprised of two subscales: positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA). Participants are asked to indicate how much he or she has experienced each of the 10 positive emotions (e.g., interested, active, proud) and the 10 negative emotions (e.g., hostile, guilty, distressed) over the past few days. Participants indicate their responses to each item using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 4 (most of the time). The total scale scores are calculated by summing the 10 PA items for the total PA score and summing the 10 NA items for the total NA scale score. The potential range of values for each total scale score is from 10 – 40. Higher scores for PA indicate higher positive affect, and higher score for NA indicate higher negative affect. The two subscales have been shown to have low correlation with each other (r = −.22), are internally consistent (Cronbach’s alpha = .84 to .87 for NA, and .86 to .90 for PA) and stable over a 2 month time period (r = .48 for PA, r = .42 for NA) (Watson et al., 1988). Reliability for the current study is α = .84 for positive affect and α = .91 for negative affect.

Self-Compassion

The Self-Compassion Scale, short form (SCS-SF; F. Raes, Pommier, Neff, & Van Gucht, 2011) is comprised of 12 items. Example items are: I try to see my failings as part of the human condition and When I’m going through a very hard time, I give myself the caring and tenderness I need. Participants indicate their responses to each item using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Almost Never) to 5 (Almost Always). To compute a total self-compassion score, negatively worded items are reverse scored, and all 12 items summed. The potential range in values is from 12–60, with higher score indicating greater self-compassion. A factor analysis indicated that the shorter version of the scale has the same factor structure as that of the full 26-item scale, that of a single first order self-compassion factor with six sub-second order factors representing the six facets of self-compassion. However, due to the brevity of the scale, it is recommended that only the total score be used, and not subscale scores (Raes et al, 2011). Reliability for this scale is good; reported Cronbach’s alphas ≥ .75 (Marshall et al., 2014; Raes et al., 2011). Correlation with the full scale is excellent; r = .97 (Raes et al., 2011). Reliability for the sample in this study is α = .79.

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured using the Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale (Huebner, 1991). A component of subjective well-being, life satisfaction refers to a judgment about one’s well-being that is beyond that which is linked directly to well-being in specific contexts. Examples of items include My life is going well and My life is better than most kids. Participants indicated their responses to each item using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (almost always). The total score was calculated by first reverse scoring items 3 and 4 and then summing the items and dividing by the number of items. The potential range of values for the total score is 0 – 3. Higher scores indicate greater life satisfaction. The 7-item scale has a unidimensional factor structure, adequate temporal stability over 1–2 weeks (correlation = 0.74 with student samples from grades 4, 6, and 8), and good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82 with student samples from grades 4, 5, 6, and 8) (Huebner, 1991). Further validation, internal consistency and test-retest reliability over one year was established in a study with 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th graders (Huebner, Funk, & Gilman, 2000). Reliability for the sample in this study is α = .84.

Perceived Stress

Perceived stress was measured using the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (S. Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). This scale is designed to assess the degree to which respondents find their lives “unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloading” (S. Cohen et al., 1983, p. 387). Examples of items include: In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way? and In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? Participants indicated their responses to each item using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Total scale score is calculated by reverse-scoring positively-worded items and then summing all 10 items. The potential range of values for the total scale score is 0 – 40. Reported reliability is .91 in college and community samples (S. Cohen et al., 1983) and .88 in a sample with early adolescents (Yarcheski & Mahon, 1999). Cronbach’s alpha for this study is α = .75.

Anxiety

The trait portion of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983) assessed general trait anxiety. The trait portion is a 20-item inventory in which participants are asked how they “generally feel.” Participants respond to items on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). Examples of items include I have disturbing thoughts and I am nervous and restless. To calculate scale scores, positively worded items are reverse-scored and all items are then summed. The potential score range is 20–80, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety. Reports of Cronbach alphas for the full scale have ranged from .86 to .95, and test-retest reliability over two months ranges from .65 to .75 (Spielberger et al., 1983). Reliability for the current study is α = .92.

Depression

The Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ; Angold, Costello, & Messer, 1995) is a self-report 13-item scale that assesses childhood and adolescent depression. Participants are asked how often the items have been true for them over the last two weeks. Examples of items include: I felt miserable or unhappy and I felt that it was hard to think properly or concentrate. Responses are indicated with a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (true). Potential total score range is 0–26, with higher scores indicating greater depression. Reliability was reported as 0.85 (Angold et al., 1995). Reliability for the sample of this study is α =.89.

Social Connectedness

The Social Connectedness Scale is an 8-item scale that assesses the sense of interpersonal belongingness and “subjective awareness of being in close relationship with the social world” (Lee & Robbins, 1998, p. 338). Examples of items include I feel disconnected from the world around me and Even around people I know, I don ’t feel like I really belong. Responses are indicated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (agree) to 6 (disagree). Scale score is computed by reverse scoring all eight items and then summing all items. The potential score range is 8 to 48, with higher scores indicating greater feelings of connectedness. Reported reliability is α=0.91 and test-retest reliability over a two week interval was .96 (Lee & Robbins, 1995). Reliability for the current study sample is α = .94.

In addition, we collected data for baseline demographics. These included information pertaining to age, gender, race/ethnicity, and level of parents’ education.

Data Analysis

To address outcomes, data were screened for outliers and dependent variables were examined for normality. We investigated whether Cohort 1 (n=16) and Cohort 2 (n=18, waitlist control) differed on baseline demographic and psychosocial variables at Time 1 with independent t-tests. Descriptive statistics were calculated for Cohort 1 and waitlist control for pre- and post-intervention for Time 1 and Time 2. To assess whether the groups differed on post values (Time 2), we conducted hierarchical regressions controlling for baseline. Next, to increase sample size and statistical power, all data from participants who completed the intervention (Cohort 1: Time 1 to Time 2, Cohort 2/ waitlist crossovers: Time 2 to Time 3) were combined and examined within group changes with paired t-tests. We also calculated Hedges’ g scores for effect size as this complies with current recommendations (Cumming, 2014; Kline, 2013; Wilkinson & APA Task Force for Statistical Inference, 1999). Hedges’ g is similar to Cohen’s d, but includes a correction factor for small samples. Nonsignificant differences with Hedges’ g greater than .20 are considered meaningful, and are interpreted according to convention: .20=small, .50=medium, .80=large (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgens, & Rothstein, 2009; J. Cohen, 1988). Finally, hierarchical regressions were conducted to examine whether changes in mindfulness and self-compassion predicted changes in the psychosocial outcomes.

Results

Feasibility and Acceptability

To determine feasibility of the intervention for an adolescent population, we investigated attendance and retention. To determine acceptability, we investigated qualitative data via participants’ in-class discussions.

Cohort 1 had one class (Class 3) cancelled due to extreme winter weather conditions, resulting in a total of 5 classes. To make up for the missed curriculum, the next class (Class 4) was held for a longer period of time (2.5 hours). Cohort 2 was able to follow the protocol for 6 total classes. Therefore, class attendance proportion (# classes attended/ total # classes) was calculated separately for each group. Additionally, we report the frequency and percentages of absences separately for each group.

Attendance was good, with a mean attendance proportion of M= 0.89, SD=0.14 for Cohort 1and M= 0.78, SD=0.12 for Cohort 2. No more than 2 classes were missed in Cohort 1 (13% missed 2 classes) and Cohort 2 (46% missed 2 classes). Youth participants attending 62% – 66% of classes have been considered “completers” in other studies (e.g., Britton et al., 2010; Sibinga et al., 2008). Reasons for a slightly lower attendance in Cohort 2 may have been due to the time of year (e.g., school final exams, Advanced Placement exams).

After enrollment, two participants withdrew (one before the first class, one after the first class) due to schedule conflicts. Another participant was withdrawn because she did not attend any classes, and two other participants were withdrawn prior to the administration of the final survey because they missed three or more classes. This resulted in a retention rate of 86%.

To assess home practice completion, participants reported the number of days per week they engaged in home practice. The participants reported an average of 2.01 days per week of home practice (SD=1.46; range 0 to 7 days). The cohorts did not differ on the total number of home practice days [t(27)= 0.310, p=0.76)] or on average days of home practice per week [t(27)= −0.09, p=0.93].

To analyze qualitative data, transcriptions of audiorecorded classes were imported into Atlas-ti 7.5 software which was used to analyze transcriptions based on conventional content analysis, a process in which codes are derived directly from data (Hseih & Shannon, 2005). Transcriptions were reviewed to obtain a broad understanding of the class discussions as they relate to the research questions. Memos were created in Atlas-ti to describe initial impressions of potential concepts emerging from the data. Second, inductive coding was conducted; text segments ranging from a few words to a paragraph (depending on extent of text needed to establish meaning) that related to acceptability of the program were assigned codes (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). After all transcriptions were provided with initial codes, connections were identified between the initial codes and these were grouped together by theme. The node function in Atlas-ti facilitated this process. Finally, these groupings were linked together with the objective of discerning overarching categories that emerged from the in-class discussions and related to the acceptability of the intervention.

Overall, there were five overarching categories that described acceptability of the intervention. These were defined as: Favorite elements of program, Suggestions for changes, Enhanced understanding of the concept of self-compassion, Self-compassion implemented in daily lives, and Engagement in class.

Favorite elements of program

In general, the practices that participants preferred were those that were more concrete, and involved noting direct, physical sensations. For example, a number of participants voiced that they liked the self-compassionate body scan and found it very relaxing. One participant stated, “It felt like a power nap… How long was it, 15 minutes? It felt like hours!” Another agreed, “I felt really tired today because I didn’t get much sleep last night. Now I feel better.”

Several others stated that the tool that was most useful for them was the here-and-now stone. The here-and-now stone is a polished stone that the participants were given to keep with them as a touchpoint to facilitate letting go of worries about the future or past, and to bring awareness into the present moment. The fact that it was portable made it possible to implement the practice in the moment when participants were experiencing stress. “I really liked the here-and-now stone. Yeah, especially during AP testing. I brought that with me and that was like phenomenal. It really helped.” Another participant recognized that the stone was simply a tool to bring them into the present moment, and that this could be extended to any other physical object.

I misplaced mine; I used other things that I had in my pocket like my phone. I would just like, fiddle with it, just kind of rub things, and be like Oh! … I think it would be helpful to emphasize that it doesn’t have to be the stone.

Another participant expressed that the soothing touch practice was helpful. In this practice, participants are encouraged to put a hand on their heart, or some other soothing gesture that involves physical touch. This practice is often used in conjunction with expressing silent loving-kindness intentions either towards oneself or someone else. In the following quote, the participant expresses that the physical gesture was comforting and facilitated her feeling more connected with a loved one.

I felt like having my hands across my chest was very anchoring. The person who I was imagining isn’t here anymore, so it kind of helped me feel more present, more connected with the imaginary. I really liked it; it was something different for me. It was nice. Very relaxing and comforting.

In addition to the concrete skills that were introduced in the class, a number of participants voiced that learning about the components of self-compassion was helpful. Specifically, several participants articulated that the common humanity component of self-compassion was particularly powerful for them.

What I got most out of this class was reinstating the common humanity. Like whatever you’re feeling, you’re not alone in it. Somebody else will feel the same way, will know where you’re coming from, even if you think that no one understands, there will be somebody who does.

Another participant elucidated how the practice of repeating common humanity phrases in the context of “A Moment for Me”, another informal practice, allowed the concept of common humanity itself to emerge, “I got a lot out of the common humanity which I was originally saying to myself kind of jokingly, but then it turned more real after a while.” Another participant articulated that the mindfulness aspect helped with focus and schoolwork.

Mindfulness has helped me focus because every day. I have like 20 pages to read in APUSH and APES [AP US History and AP Environmental Science], and somehow right now it is hard to get reading, and every day I would come home and think ‘I don’t want to do this’, and so I wouldn’t, but if I sat down and focused only on this and nothing else then I got it done and it didn’t even take that long. So I actually like meditating and …focusing on my breath, because it helped me focus on my schoolwork.

Suggestions for changes

Although there were fewer comments related to aspects of the program that were less appealing to participants than those that were appealing, participants commented about certain aspects of the program that did not work as well for them, and made suggestions for changes. Mostly, these were related to the formal home practices. Participants felt that it was inconvenient and time consuming to go to a website to listen to guided meditations, as was suggested, and felt that the meditations on the website were too long. In contrast, the “in-the-moment” practices, those that could be done at the moment when feeling stressed (such as the here-and-now stone) were more useful.

Brush your teeth mindfully, I do that every day, but like I wouldn’t go out of my way to go online, like if you want people to do them [home practices] really well, like a lot, then I would suggest it not having it be something like getting a book and reading about mindfulness or going online, it would be something you could remember while you were doing it, like ‘Oh! I’m supposed to be mindful right now!’

Another participant agreed with this sentiment, “Going to some mindfulness site every day just isn’t part of my routine….” In addition, participants commented that there were no consequences for not doing homework, and therefore attending to it was low priority in the busy lives of these teens.

Yeah, that just wasn’t a priority for me. I have a ton of homework every day. When I get home, I just think about my homework and what I have to do for the next day at school. Because this class was once a week for only six weeks, it wasn’t what I was thinking about.

Another participant mentioned, “There aren’t as heavy consequences here if you don’t do your homework.” Due to these factors, a number of the participants found it difficult to complete the formal at-home practices. However, at least one participant disagreed and was able to make it part of her routine.

For me, it didn’t really feel like homework. To me, it was just like part of my daily routine. It’s just like adding an extra step which would be going online and listening to something … it helped a lot more, it helped. It was different. It was a change.

Participants suggested that an email be sent halfway through the week in between classes as a reminder to do the homework practice. Finally, several participants suggested that there be more clarification around the concept of mindfulness.

There was a definition [of mindfulness] but I feel like I missed something, other people explained it to me, and now I feel like I kind of get it. If I understood more of what mindfulness was and of its benefits, actual hardcore benefits, then I would have listened to the meditations more and gotten more out of it than I did.

Enhanced understanding of the concept of self-compassion

Over the course of the 6-week program, participants developed a greater understanding of the construct of self-compassion. One participant commented about how one’s sense of self can be enhanced through implementing this construct, instead of their self-concept being based on how well they performed a task. For example, they can perceive themselves as ‘good’ regardless of their performance. “I think what it’s basically saying is instead of telling people it’s ok you did this good, which they then connect to I’m a good person, [you’re saying] it’s okay you did this poorly, you messed up, but it’s ok.” Another participant expressed that understanding self-compassion helped her change the way she relates to her schoolwork, thereby decreasing anxiety.

I guess I’m thankful for the tools that I’ve learned, because I get a lot of anxiety about school, especially. I feel like in the last few weeks my anxiety in the moment has decreased because I’m mindful and compassionate toward myself, and I don’t know, I feel much better about a lot of stuff I have to do, because I know it’s not the end of the world if I don’t do it or whatever.

Similarly, another participant explained that the program brought her the ability and awareness to discern which tasks absolutely had to be attended to immediately versus those that could wait.

I think mindful self-compassion is about being in tune with yourself and being able to know what is going on so that you can judge better ‘OK, this is a thing that I need to do’ versus ‘This is something that I can give myself a rest with.’ You know, mindfulness is about really being aware of what is going on emotionally and physically for you so that you can make that decision.

Self-compassion implemented in daily lives

Throughout the program, participants related how they were able to implement the self-compassion tools that they learned in class to contend with the stressors or difficulties that arose in their daily lives. In the quote below, one participant demonstrated her new ability to not ruminate on a mistake she had made.

I forgot my brother’s birthday today. I just left the house and I felt really bad and I emailed him and I emailed my mom … I guess I sort of used the self-compassion thing because I was like ‘Ok, I can’t do anything, and I didn’t really dwell on it all day.

Another participant related how she was able to improve her ability to fall asleep. “I used the mindfulness stuff and that’s pretty cool because the body scan helps me fall asleep at night.” A third participant demonstrated her ability to maintain perspective and hence keep stress at bay, “I’ve tried the self-compassion break [“A Moment for Me”] a few times like when I’m really stressed out about something. I just take a break and put it into perspective and say it’s not really that big a deal.” When adolescents experienced heightened emotions that seemed to have no apparent cause, mindful self-compassion tools were useful, “There were a couple of times when I felt anxious for no real reason but I tried to use the mindfulness stuff and it helped a little bit.”

Engagement in class

In general, students were actively engaged in class throughout the 6-week program. The program involved hands-on activities, often in small groups, rather than in a lecture format, and this facilitated student involvement. Also, the participants seemed able to see the relevance that the in-class practices had to their daily lives outside of class. For example, after an activity that used their senses to pay close attention to a piece of chocolate (i.e., mindful eating), participants agreed that they were not worrying or ruminating about events in their daily lives when engaged in the activity because they were able to focus on the present experience of tasting or feeling the texture of the chocolate. When asked what it would be like if people paid as much attention to aspects in their lives as they did during the mindful eating activity, one participant answered, “You would savor it more.” Another teen elaborated, “I think people would be closer … If you aren’t really listening to someone, you can’t understand what they’re saying. If neither of you is paying attention to the other, it’s almost like two separate conversations going on.”

Engagement in class also facilitated participants’ understanding of how self-acceptance could be strengthened. One participant commented,

Even if you’re a little too loud or a bit too talkative in groups, or if you’re single-minded about one subject, or if you’re kind of selfish, or bad at problem-solving, or whatever, that’s just a part of who you are and that’s ok!

This was affirmed by another participant, “We all have flaws because we are human beings and we have to accept our flaws as flaws.” The essence of the program is that teens can learn how to be a friend to themselves and this is supported through the compassionate friend meditation, a guided meditation which facilitates this process. One participant grasped the essence of the program when she shared, “I always feel that I have to have someone else to prove that I can do things. But I have myself, and that is someone!”

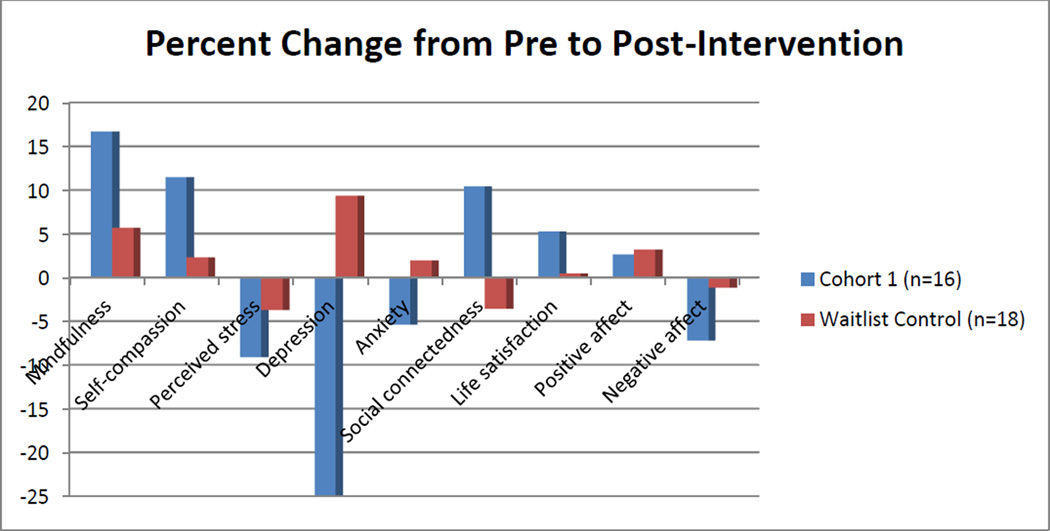

In the first step of the analysis of quantitative data, we determined that Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 (waitlist control) did not significantly differ on baseline demographic and psychosocial variables at Time 1 with independent t-tests (all p ’s > .05). Descriptive statistics for Cohort 1 and the waitlist control group at Time 1 and Time 2 are displayed in Table 1. Next, we compared Cohort 1 and the waitlist group on their post psychosocial outcomes (Time 2; i.e., before Cohort 2 received the intervention) with hierarchical regressions that controlled for baseline. The results indicated that Cohort 1 had significantly greater self-compassion (β= .24, p= .049) and trends for greater mindfulness (β= .20, p=.08) than the waitlist group (see Table 2). Additionally, Cohort 1 reported significantly greater life satisfaction (β= .30, p=.04), lower depression (β= −.27, p=.004), and evidence of trends for anxiety (β = −.20, p=.098) and social connectedness (β= .21, p=.097) compared to the waitlist group. Percent change of the psychosocial outcomes from Time 1 to Time 2 are depicted in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Cohort 1 and Waitlist at Time 1 and Time 2, and Change

| Cohort 1 M(SD) n=16 |

Waitlist M(SD) n=18 |

|

|---|---|---|

| CAMM | ||

| Pre (Time 1) | 20.19 (5.78) | 18.61(6.54) |

| Post (Time 2) | 23.56 (5.35) | 19.67 (7.30) |

| Change [95% CI] | 3.37(4.49) | 1.06 (3.95) |

| [−5.77, −.99] | [−3.02, .91] | |

| SCS | ||

| Pre (Time 1) | 2.79 (.17) | 2.62 (.67) |

| Post (Time 2) | 3.11 (.43) | 2.68 (.74) |

| Change [95% CI] | .32 (.63) | .06 (.29) |

| [−.65, .02] | [−.21, .08] | |

| PSS | ||

| Pre (Time 1) | 23.33 (5.11) | 26.94 (5.27) |

| Post (Time 2) | 21.20 (4.62) | 25.94 (6.90) |

| Change [95% CI] | −2.13 (4.72) | −1.00 (3.82) |

| [−.48, 4.75] | [−.97, 2.97] | |

| SMFQ | ||

| Pre (Time 1) | 9.00 (5.97) | 9.50 (6.59) |

| Post (Time 2) | 6.75 (5.09) | 10.39 (6.63) |

| Change [95% CI] | −2.25 (3.70) | .89 (2.74) |

| [.28, 4.22] | [−2.25, .47] | |

| STAI | ||

| Pre (Time 1) | 47.31(9.42) | 51.22 (12.45) |

| Post (Time 2) | 44.75 (8.45) | 52.22 (13.22) |

| Change [95% CI] | −2.56 (10.48) | 1.00 (4.77) |

| [−3.02, 8.15] | [−3.37, 1.37] | |

| CONN | ||

| Pre (Time 1) | 33.06 (8.85) | 32.61 (13.14) |

| Post (Time 2) | 36.50 (8.60) | 31.44 (12.89) |

| Change [95% CI] | 3.44 (10.17) | −1.17 (7.19) |

| [−8.85, 1.98] | [−2.41, 4.74] | |

| SLSS | ||

| Pre (Time 1) | 24.75 (3.19) | 22.56 (4.85) |

| Post (Time 2) | 26.06 (3.43) | 22.67 (3.87) |

| Change [95% CI] | 1.31 (4.33) | .11 (3.18) |

| [−3.62, 1.00] | [−2.41, 4.74] | |

| PA | ||

| Pre (Time 1) | 3.01 (.65) | 2.80 (.56) |

| Post (Time 2) | 3.09 (.59) | 2.89 (.66) |

| Change [95% CI] | .08 (.50) | .09 (.41) |

| [−.35, .18] | [−.30, .11] | |

| NA | ||

| Pre (Time 1) | 2.49 (.76) | 2.50 (.96) |

| Post (Time 2) | 2.31 (.70) | 2.47 (1.01) |

| Change [95% CI] | −.18 (.77) | −.03 (.43) |

| [−.22, .60] | [−.19, .24] |

Note. Change is Time 2 – Time 1. CAMM=Children and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure, SCS=Self-compassion Scale, PSS=Perceived Stress Scale, SMFQ=Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-short form, STAI=Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Scale (trait subscale), CONN=Social Connectedness Scale, SLSS=Student Life Satisfaction Scale, PA=Positive Affect subscale of PANAS, NA=Negative Affect subscale of PANAS; CI=confidence interval

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regressions of Study group (Cohort 1 and Waitlist) Predicting Post Study Outcomes (Time 2), Controlling for Baseline (N= 34)

| Outcome | B | SE B | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAMM | 2.61 | 1.42 | .20† | .64 | .04 | 27.84*** |

| SCS | .31 | .15 | .24* | .58 | .06 | 21.13*** |

| SMFQ | −3.23 | 1.05 | −.27** | .77 | .07 | 51.34*** |

| STAI | −4.53 | 2.66 | −.20† | .60 | .04 | 23.56*** |

| CONN | 4.75 | 2.77 | .21† | .51 | .05 | 16.42*** |

| SLSS | 2.34 | 1.11 | .30* | .43 | .08 | 11.50*** |

| PA | .04 | .15 | .04 | .54 | .001 | 18.46*** |

| NA | −.16 | .20 | −.09 | .57 | .01 | 20.69*** |

| PSS | −1.79 | 1.59 | −.14 | .58 | .02 | 20.13*** |

Note. Cohort 1=1, Waitlist = 0. ΔR2= change from the first step that included the baseline. CAMM=Children and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure, SCS=Self-compassion Scale, PSS=Perceived Stress Scale, SMFQ=Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-short form, STAI=Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Scale (trait subscale), CONN=Social Connectedness Scale, SLSS=Student Life Satisfaction Scale, PA=Positive Affect subscale of PANAS, NA=Negative Affect subscale of PANAS;

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Figure 2.

Percent change for outcomes for Cohort 1 and Waitlist control from Time 1 to Time 2.

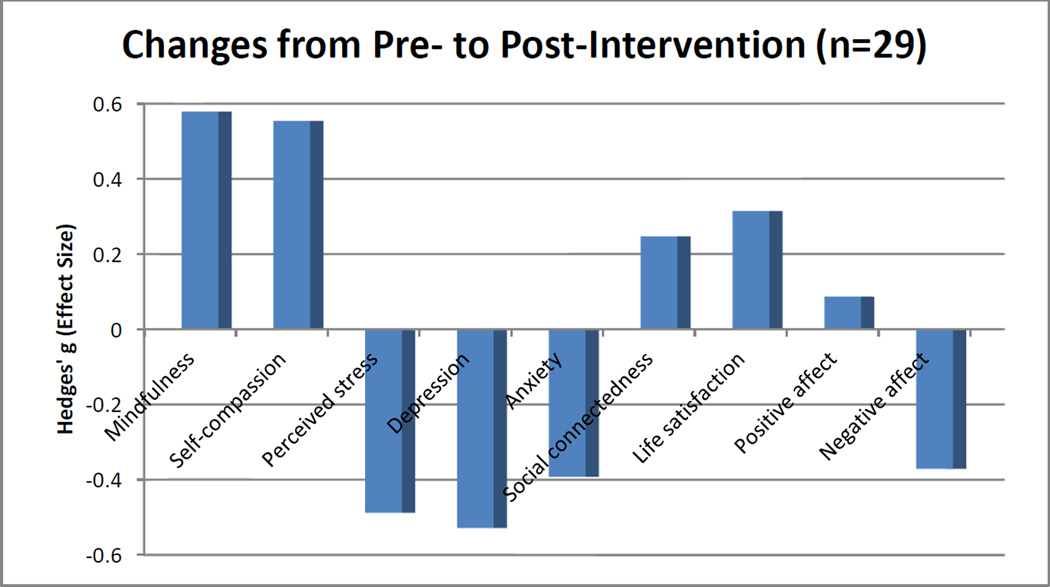

There were no significant differences between the two groups at Time 1 (baseline), and the crossover design allowed us to combine data from the two cohorts’ intervention periods. This increased the sample size and statistical power and enabled us to examine changes over the intervention periods. Paired t -tests indicated significant changes in self-compassion (p= .005) and mindfulness (p< .001). Additionally, there were significant changes in anxiety (p= .015), depression (p= .001), perceived stress (p= .032), and negative affect (p= .027). Hedges’ g results demonstrated a small to medium effect size in these variables (range = .37 to .58; see Table 3 and Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics at Pre- and Post-Intervention for the combined cohorts’ intervention period (N=29)

| Pre M(SD) | Post M(SD) | t-value | Hedges’ g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAMM | 20.00 (6.50) | 23.72 (5.92) | −4.64*** | 0.58 |

| SCS | 2.75 (0.71) | 3.11 (0.51) | −3.08** | 0.55 |

| PSS | 25.00 (6.21) | 22.23 (4.55) | 2.28* | 0.49 |

| SMFQ | 9.83 (6.22) | 6.69 (4.49) | 3.93** | 0.53 |

| STAI | 49.07 (11.51) | 44.66 (10.16) | 2.59* | 0.39 |

| CONN | 32.79 (10.17) | 35.31 (9.64) | −1.52 | 0.25 |

| SLSS | 23.97 (3.56) | 25.24 (4.25) | −1.66 | 0.32 |

| PA | 2.97 (0.59) | 3.02 (0.65) | −0.49 | 0.09 |

| NA | 2.49 (0.88) | 2.18 (0.69) | 2.33* | 0.37 |

Note. Cohort 1 intervention period is Time 1 to Time 2, and Cohort 2 intervention period is Time 2 to Time 3; CAMM=Children and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure, SCS=Self-compassion Scale, PSS=Perceived Stress Scale, SMFQ=Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-short form, STAI=Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Scale (trait subscale), CONN=Social Connectedness Scale, SLSS=Student Life Satisfaction Scale, PA=Positive Affect subscale of PANAS, NA=Negative Affect subscale of PANAS;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Figure 3.

Changes from pre- to post-intervention in combined cohorts (includes waitlist crossovers); Hedges’ g small effect=.20, medium effect =.50, large effect=.80

To investigate whether changes in self-compassion and mindfulness were associated with changes in psychosocial outcomes, hierarchical regressions were conducted with the data from the combined cohorts’ intervention periods. When controlling for baseline values of self-compassion and the outcome variables, increases in self-compassion predicted increases in life satisfaction (β = 0.61, p = .001), along with decreases in anxiety (β = −0.48, p = .01) and perceived stress (β = −0.49, p = .02). Increases in self-compassion marginally predicted increases in social connectedness (β = 0.31, p = .09). Changes in self-compassion did not significantly predict changes in depression, positive affect, or negative affect (p’s >.30) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hierarchical Regressions for Changes in Self-Compassion Predicting Changes in Emotional Wellbeing Outcomes (N = 29)

| Outcome | B | B SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSS | −5.18 | 1.98 | −0.49* | 0.27 | 0.20 | 4.06* |

| SMFQ | −0.68 | 1.42 | −0.08 | 0.48 | <0.01 | 9.58*** |

| STAI | −9.61 | 2.94 | −0.48** | 0.55 | 0.17 | 12.48*** |

| CONN | 5.85 | 3.33 | 0.31† | 0.36 | 0.07 | 6.25** |

| SLSS | 5.10 | 1.42 | 0.61** | 0.41 | 0.27 | 7.54** |

| PA | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 3.59* |

| NA | −0.16 | 0.21 | −0.12 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 9.56*** |

Note. Data includes both cohorts’ interention periods. PSS=Perceived Stress Scale, SMFQ=Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-short form, STAI=Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Scale (trait subscale), CONN=Social Connectedness Scale, SLSS=Student Life Satisfaction Scale, PA=Positive Affect subscale of PANAS, NA=Negative Affect subscale of PANAS, R2 = Variance accounted for by the full regression model, ΔR2 = Variance accounted for by the addition of Self-compassion Scale to the model,

p < . 10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

We then examined the predictive ability of changes in mindfulness on changes in the psychosocial outcome variables. When controlling for baseline values of mindfulness and the outcome variables, changes in mindfulness predicted decreases in depression (β = −0.49, p = .01) and anxiety (β = −0.59, p = .01). Mindfulness was not a significant predictor for the remaining variables (p’s>.10) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Hierarchical Regressions for Changes in Mindfulness Predicting Changes in Emotional Wellbeing Outcomes (N = 29)

| Outcome | B | B SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSS | −0.11 | 0.23 | −0.13 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.29 |

| SMFQ | −0.37 | 0.14 | −0.49* | 0.63 | .09 | 16.70*** |

| STAI | −1.01 | 0.34 | −0.59** | 0.55 | 0.14 | 12.26*** |

| CONN | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 5.23** |

| SLSS | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 3.07* |

| PA | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 3.82* |

| NA | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.40 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 6.76** |

Note. Data includes both cohorts’ intervention periods. PSS=Perceived Stress Scale, SMFQ=Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-short form, STAI=Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Scale (trait subscale), CONN=Social Connectedness Scale, SLSS=Student Life Satisfaction Scale, PA=Positive Affect subscale of PANAS, NA=Negative Affect subscale of PANAS, R2 = Variance accounted for by the full regression model, ΔR2 = Variance accounted for by the addition of Children and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure to the model.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Because increases in self-compassion and mindfulness predicted decreases in anxiety independently, we conducted a hierarchical regression (controlling for baselines) to determine if they remained significant predictors of decreases in anxiety when both were included in the model. As a set, changes in self-compassion and mindfulness explained 30% of the variance for anxiety (F (1, 23) =11.39, p=.003. Increases in self-compassion (β = −0.45, p = .001) and mindfulness (β = −0.55, p = .001) had unique predictive ability on decreases in anxiety, when controlling for the other.

As an exploratory analysis, we investigated whether home practice was related to change in mindfulness or self-compassion. Bivariate correlations indicated that the number of home practice days per week was not significantly associated with change in mindfulness or self-compassion (p’s > 0.05). This may be a result of the low number of days of home practice overall.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary outcomes of “Making Friends With Yourself: A Mindful Self-compassion Program for Teens.” This is a new program for adolescents that introduces the concepts of both mindfulness and self-compassion, while providing opportunities for hands-on practice of mindfulness and self-compassion skills. The program was found to be feasible, as demonstrated by attendance and retention rates. Attendance rate was good, with students attending 89% (Cohort 1) and 78% (Cohort 2) of the sessions. Retention rate was good as well; 86% of the adolescents completed the program.

Acceptability of the program was determined by qualitative data provided through in-class discussions and homework completion. Qualitative analyses indicated that the program was generally well-liked by participants. Adolescents found the concepts of self-compassion and mindfulness to be applicable and useful in their daily lives, felt that they benefited from coming to class, and indicated that they used the practices during moments of stress. In particular, the tools that were most favored by participants were those that involved noticing direct physical sensations, such as the body scan and the here-and-now stone. Although adolescents indicated that the informal practices were useful, they felt that the formal at-home practices that involved accessing a website and listening to guided meditations were less helpful. Teens found it troublesome to remember to do the home practice because it was not part of their daily routine. Additionally, they expressed that the guided meditations on the website were too long. This was also reflected in their lack of home practice, which averaged only two days per week.

Despite the lack of home practice, however, participants in Cohort 1 evidenced significantly greater post-intervention scores than the waitlist control group in self-compassion and life satisfaction with trends towards significance in mindfulness and social connectedness, and significantly lower depression scores, with trends towards significance in anxiety. When data from both cohorts were combined and pre-post measures were investigated, self-compassion and mindfulness improved significantly pre to post as well as all the negatively-worded psychosocial outcomes (i.e., depression, anxiety, perceived stress, negative affect). Interestingly, none of the positively-worded measures improved significantly pre to post. It has been suggested that adolescents may more easily relate to negatively-worded items than those that are positively-worded and therefore respond to negatively-worded items more conclusively (Bluth & Blanton, 2014a).

Effect sizes for the combined groups’ outcomes during intervention periods were in the small to medium range for all variables, with the exception of positive affect, which demonstrated no meaningful effect. In particular, the largest effect sizes were evidenced with depression, anxiety, and stress. Similar findings are reported in a meta-analyses on self-compassion studies with adults, which found a large effect size when correlating self-compassion with psychopathology, defined by combining stress, anxiety and depression (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012).

Further, both mindfulness and self-compassion improved across this 6-week program, demonstrating that these traits may be modifiable and can be enhanced with practice. Results from regression analyses indicated that increases in mindfulness predict decreases in depression and anxiety. Further, increases in self-compassion predict decreases in perceived stress and anxiety, and increases in life satisfaction; both mindfulness and self-compassion uniquely predict decreases in anxiety. This evidence supports the hypothesis that “Making Friends With Yourself”, a program which incorporates mindfulness and self-compassion practices, can be effective in reducing depression, stress, and anxiety and improving overall emotional health in adolescents.

Interestingly, results indicated that at-home practice was not correlated with increases in mindfulness or self-compassion. In other words, self-compassion and mindfulness improved significantly from pre- to post-intervention despite the lack of at-home practice. Attending the weekly class and possibly reflecting on them during the week appeared to be sufficient to improve mindfulness and self-compassion as these changes were not evident in the waitlist control. As there is a lacuna in research on home practice in mindfulness-based interventions among adolescents, further research is necessary to definitively support these findings.

A number of modifications will be made in future iterations of this program in response to the feedback of the participants in this study. For example, recognizing that the guided meditations on the website were created for adults, plans are underway to create a website with shorter, developmentally-appropriate guided meditations for teens. As some teens found accessing a website to be time-consuming, a phone app with short guided meditations and practice reminders will be created. Additionally, halfway through each week, participants will be emailed reminders to do their home practice. As broader literature on interventions among adolescents (i.e., cognitive behavioral therapy) indicates that homework adherence is improved by providing a clear rationale for the homework, spending more time explaining the homework, and troubleshooting obstacles to homework practice, these factors will be emphasized in future iterations of MFY (Jungbluth & Shirk, 2013). Further, as in-the-moment practices (i.e., A Moment for Me) were more acceptable to teens, these practices will be emphasized in the next iteration of this program. Finally, the program will be expanded from 6 to 8 weeks to include greater mindfulness discussion and practice, as several participants indicated that this concept could have been more clearly explained.

This study has a number of limitations that are common in pilot studies. First, the sample size was small, and the demographics indicated that these adolescents were mostly female and came largely from well-educated families, limiting generalizability. Further, it would have been helpful to ask participants weekly which of the informal and formal practices they used each week. In addition, future studies should include follow-up measures to determine if changes that were evidenced post-intervention would be stable over time. There are also limitations inherent in a waitlist control; that is, there may be an overestimate of effects on the treatment group. It is recommended that future studies utilize an active control.

Overall, these preliminary findings indicate that “Making Friends With Yourself: A Mindful Self-Compassion Program for Teens” is feasible and acceptable to adolescents, and promotes increases in mindfulness and self-compassion that can be instrumental in improving psychological outcomes. An additional strength of our study is that we have contributed longitudinal evidence of these changes to a literature that has mainly consisted of cross-sectional studies. Providing teens with skills to develop and strengthen self-compassion may protect against depression and anxiety disorders in this critical developmental stage. Future research should investigate more long-term outcomes and potential mechanisms for these findings.

Acknowledgments

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was funded by the University of North Carolina University Research Council and in part by grant number T32AT003378-04 from the National Center on Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). Analyses and conclusions are the responsibility of the authors rather than the funders. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Footnotes

No authors have any conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Karen Bluth, Email: bluth@med.unc.edu.

Susan A. Gaylord, Email: gaylords@med.unc.edu.

Rebecca A. Campo, Email: Rebecca_campo@med.unc.edu.

Michael C. Mullarkey, Email: michael.mullarkey@utexas.edu.

Lorraine Hobbs, Email: jalhobbs@yahoo.com.

References

- Akin U, Akin A. Examining the predictive role of self-compassion on sense of community in Turkish adolescents. Social Indicators Research. 2014:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Albano AM, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Childhood anxiety disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child psychopathology. New York, NY: Guilford; 2003. pp. 279–329. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1995;5:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Barry CT, Loflin DC, Doucette H. Adolescent self-compassion: Associations with narcissism, self-esteem, aggression, and internalizing symptoms in at-risk males. Journal of Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;77:118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Biegel G, Brown K, Shapiro S, Schubert C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology. 2009;77(5):855–866. doi: 10.1037/a0016241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluth K, Blanton P. The influence of self-compassion on emotional well-being among early and older adolescent males and females. Journal of Positive Psychology. 2014a doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.936967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluth K, Blanton P. Mindfulness and self-compassion: Exploring pathways of adolescent wellbeing. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014b;23(7):1298–1309. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9830-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgens JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, U.K: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Britton W, Bootzin R, Cousins J, Hasler B, Peck T, Shapiro S. The contribution of mindfulness practice to a multicomponent behavioral sleep intervention following substance abuse treatment in adolescents: A treatment-development study. Substance Abuse. 2010;31:86–97. doi: 10.1080/08897071003641297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick P, Metz S. Learning to BREATHE: A pilot trial of a mindfulness curriculum for adolescents. Advances in school mental health promotion. 2009;2(1):35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, West, Loverich, Biegel Assessing adolescent mindfulness: Validation of an adapted Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in adolescent normative and psychiatric populations. Psychological Assessment. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0021338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti E, Klimstra T, Keijsers L, Hale WW, Meeus W. Anxiety trajectories and identity development in adolescence: A five-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:839–849. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9302-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G. The new statistics: Why and how. Psychological Science. 2014;25:7–29. doi: 10.1177/0956797613504966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd J. The teen brain: Insights from neuroimaging. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:321–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco L, Baer RA, Smith GT. Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the child and adolescent mindfulness measure (CAMM) Psychological Assessment. 2011;23(3):606–614. doi: 10.1037/a0022819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AG, Hill RM, King CA. Specific coping behaviors in relation to adolescent depression and suicidal ideation. Journal of adolescence. 2011;34(5):1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hseih HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner ES. Initial Development of the Student's Life Satisfaction Scale. School Psychology International. 1991;12(3):231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner ES, Funk BA, Gilman R. Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Psychosocial Correlates of Adolescent Life Satisfaction Reports. Canadian Journal of School Psychology. 2000;16(1):53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jungbluth NJ, Shirk SR. Promoting homework adherence in cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(4):545–553. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.743105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness in Everyday Life. New York: Hyperion; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Beyond significance testing: Statistics reform in the behavioral sciences. Washington, D. C: APA Books; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc JC, Almudevar A, Brooks SJ, Kutcher S. Screening for adolescent depression: comparison of the Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale with the Beck depression inventory. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2002;12(2):113–126. doi: 10.1089/104454602760219153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Robbins SB. Measuring Belongingness - the Social Connectedness and the Social Assurance Scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1995;42(2):232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Robbins SB. The relationship between social connectedness and anxiety, self-esteem, and social identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1998;45:338–345. [Google Scholar]

- MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(6):545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SL, Parker PD, Ciarrochi J, Sahdra B, Jackson CJ, Heaven PCL. Self-compassion protects against the negative effects of low self-esteem: A longitudinal study in a large adolescent sample. Journal of Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;74:116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson T, Greenberg M, Dariotis JK, Gould LF, Rhoades BL, Leaf PJ. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:985–994. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity. 2003;2:85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Germer C. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jclp.21923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, McGehee P. Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and Identity. 2010;9(3):225–240. [Google Scholar]

- Raes F. The effect of self-compassion on the development of depression symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Mindfulness. 2011;2(1):33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2011;18(3):250–255. doi: 10.1002/cpp.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonert-Reichl KA, Lawlor MS. The effects of a mindfulness-based education program on pre- and early adolescents’ well-being and social and emotional competence. Mindfulness. 2010;1(3):137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga E, Stewart M, Mahyar T, Welsh CK, Hutton N, Ellen JM. Mindfulness-Based stress reduction for HIV-infected youth: A pilot study. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2008;4:36–37. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets E, Neff K, Alberts H, Peters M. Meeting Suffering With Kindness: Effects of a Brief Self-Compassion Intervention for Female College Students. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014;70:794–807. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basis of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Susman E, Dorn L. Puberty: Its role in development. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Third. New York: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Wekerle C, Schmuck ML, Pagila-Boak A. The linkages among childhood maltreatment, adolescent mental health, and self-compassion in child welfare adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2011;35:887–898. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson T, Clark L, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson L APA Task Force in Statistical Inference. Statistical methods for psychology journals: Guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist. 1999;54:594–604. [Google Scholar]

- Yarcheski A, Mahon N. The moderator-mediator role of social support in early adolescence. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1999;21(5):685–698. doi: 10.1177/01939459922044126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller M, Yuval K, Nitzan-Assayag Y, Bernstein A. Self-compassion in recovery following potentially traumatic stress: Longitudinal study of at-risk youth. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2014;43(4):645–653. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9937-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]