Abstract

Little is known about the immigrant Latino/a transgender community in the southeastern United States. This study used photovoice, a methodology aligned with community-based participatory research, to explore needs, assets, and priorities of Latina transgender women in North Carolina. Nine immigrant Latina male-to-female transgender women documented their daily experiences through photography, engaged in empowerment-based photo-discussions, and organized a bilingual community forum to move knowledge to action. From the participants’ photographs and words, 11 themes emerged in three domains: daily challenges (e.g., health risks, uncertainty about the future, discrimination, and anxiety about family reactions); needs and priorities (e.g., health and social services, emotional support, and collective action); and community strengths and assets (e.g., supportive individuals and institutions, wisdom through lived experiences, and personal and professional goals). At the community forum, 60 influential advocates, including Latina transgender women, representatives from community-based organizations, health and social service providers, and law enforcement, reviewed findings and identified ten recommended actions. Overall, photovoice served to obtain rich qualitative insight into the lived experiences of Latina transgender women that was then shared with local leaders and agencies to help address priorities.

Introduction

The proportion of the US population that identifies as Latino has expanded considerably during the past two decades. Between the 2000 and 2010 censuses, the Latino population in the United States (US) grew by 43%. In North Carolina (NC), the number of Latinos grew by 111%, giving NC one of the fastest-growing Latino populations in the US (US Census Bureau, 2014). NC ranks sixth in the nation in the number of Latinos who are foreign born; over half of Latinos in the state are foreign born and 61% of these are originally from Mexico.

Much of this new growth has occurred in the southeastern US (Painter, 2008; Southern AIDS Coalition, 2012). Job opportunities in farm work, construction, and factories, coupled with dissatisfaction with the quality of life in traditional US destinations, have led many immigrants to leave higher-density regions of the US and relocate to the Southeast and NC in particular. Additionally, immigrants are increasingly bypassing traditional destinations and coming to the Southeast directly (Massey & Capoferro, 2008; Painter, 2008; Rhodes et al., 2007). Compared to Latinos in states that have a history of Latino immigration (e.g., Arizona, California, Florida, New York, and Texas), immigrant Latinos in NC resemble those in the Southeast more generally; they tend to be younger and disproportionately male, come from rural communities in southern Mexico and Central America, have lower educational backgrounds, are less acculturated, and settle in communities without histories of immigration. The Southeast also lacks developed infrastructures to meet their needs (e.g., quality and adequate interpretation services (Kissinger et al., 2012; Painter, 2008; Rhodes, 2012; Rhodes, Duck, Alonzo, Daniel, & Aronson, 2013).

As Latino populations in the US and in the Southeast in particular grow, it is important to develop culturally congruent public health interventions for this community, and particularly for sub-groups such as sexual and gender minorities that may be more vulnerable and have a unique set of needs and priorities. Transgender persons of color, and non-citizen transgender persons in particular, tend to have particularly high rates of poverty; depression; HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs); physical and emotional abuse; discrimination, harassment, and violence; social isolation; alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use and abuse; and suicide and suicide attempts. They are also less likely to seek and more likely to postpone health care when needed because of a variety of barriers including lack of insurance coverage, limited transportation, discrimination, and victimization (Bazargan & Galvan, 2012; Gordon & Meyer, 2007; Grant et al., 2010; Hwahng & Nuttbrock, 2013; Institute of Medicine, 2011; Nuttbrock et al., 2013; Nuttbrock et al., 2009, 2010; Pinto, Melendez, & Spector, 2008; Reback & Fletcher, 2013; Rhodes, Daniel, et al., 2013; Rhodes et al., 2010; Vissman et al., 2011). There has been a call to improve our understanding of transgender-specific physical and mental health to inform research and intervention priorities to reduce these disparities (Grant et al., 2010; Institute of Medicine, 2011).

We sought to document the needs, assets, and priorities of immigrant Latina transgender women using photovoice, an innovative methodology closely aligned with community-based participatory research (CBPR).

Methods

The CBPR Partnership and Impetus for the Study

This study was conducted by a CBPR partnership in NC, whose members represent the lay community, organization representatives, and academic researchers. Our research focuses on designing, implementing, and evaluating interventions promoting sexual health among immigrant Latino communities (Rhodes, 2012; Rhodes, Duck, et al., 2013; Rhodes et al., 2014). Our partnership has designed our research to be inclusive of sexual and gender minorities (including self-identifying gay and bisexual men, other MSM, and transgender persons) given that we approach health and well-being from an assets-based, community-development orientation. However, as we were preparing for the implementation of two interventions to promote sexual health among Latino sexual minorities, we realized that our interventions did not acknowledge and address the contexts and concerns of transgender persons despite substantial percentages of transgender persons participating in our previous studies (Rhodes et al., 2010; Rhodes et al., 2011; Rhodes et al., 2012). For example, in a respondent-driven sampling study of Latino sexual and gender minorities, 16% of the sample self-identified as transgender (Rhodes & McCoy, 2015; Rhodes et al., 2012). Intervention curricula, materials, and logos focused on gay and bisexual men and other MSM, not transgender persons. For example, the “H” in our HOLA and HOLA en Grupos interventions stood for “hombres” (men; Rhodes, 2012; Rhodes, Daniel, et al., 2013; Rhodes et al., 2014), and yet, we knew that some participants who may meet inclusion criteria may not self-identify as men. This was especially worrisome for our partnership because during a partnership meeting, a partner pointed out that many of the transgender women participating in our projects are accustomed to non-inclusive language and would not be expecting these accommodations, as unfortunately they are accustomed to being excluded. Hearing this articulated and being uncomfortable with the rationalization, our partnership knew that we must make even more of an effort to be aware of the needs and priorities of Latino transgender persons (Rhodes et al., 2014).

Thus, we quickly revised our interventions. We no longer defined and gave meaning to the letters within the acronym HOLA in the intervention titles, for example; we removed the meaning of the acronym from logos, t-shirts, caps, and all printed materials. We also revised all facilitator language to include “transgender persons,” in addition to “gay and bisexual men and other MSM” in Spanish. We updated information to include what is known about sexual health among transgender persons, revised role plays to include transgender scenarios, and ensured that all visuals included images of transgender women.

Although our partnership had been inclusive of broad diversity, transgender persons were not members; this was not by design. Our partnership had focused on health among MSM and needed raised consciousness about the needs of transgender persons and the barriers to their inclusion in the partnership. Thus, in addition to revising our interventions to be more inclusive, our CBPR partnership embarked on a process to build trust and partnerships with and better understand the needs and priorities of immigrant Latina transgender women through photovoice.

Photovoice

A qualitative and exploratory research methodology founded on the principles of constructivism (Patton, 1990), critical theory (Morrow & Brown, 1994), health promotion (Green, Krueter, & Krueter, 1999), empowerment education (Freire, 1970, 1973), and documentary photography (Sontag, 1977; Wang & Burris, 1997), photovoice is closely aligned with CBPR (Hergenrather, Rhodes, Cowan, Bardhoshi, & Pula, 2009). Photovoice enables participants to record and critically define and reflect on their own needs, assets, and priorities and those of their community through photographic images and small-group discussion and represent and communicate to others their lived experience (Hergenrather et al., 2009; Rhodes et al., 2009). Rather than an academic researcher or practitioner (e.g., health educator and clinician) defining the focus of the research, photovoice allows participants to define the research question. Members of our partnership did not want to determine what to focus on behalf of transgender women. Instead, photovoice promotes a partnership approach with participants who drive the research process. Thus, unlike focus groups, as an example, photovoice is a flexible method in which participants themselves can determine what to focus on as there is no need for predetermined focus.

Furthermore, when done well, the methodology allows rich detail to emerge through a process that ensures that the lived experiences of participants are identified and interpreted through ongoing critical dialogue; photovoice ensures that the community’s priorities are represented by their own words and images. Photovoice differs from most traditional approaches to research in which power is held by the academic researcher rather than the participants (Hergenrather et al., 2009; Streng et al., 2004; Wang & Burris, 1997). A hallmark of CBPR is multilevel action, including individual, group, community, policy, and social change (Rhodes, Duck, et al., 2013). Similarly, the photovoice process focuses on movement toward solutions (Hergenrather et al., 2009).

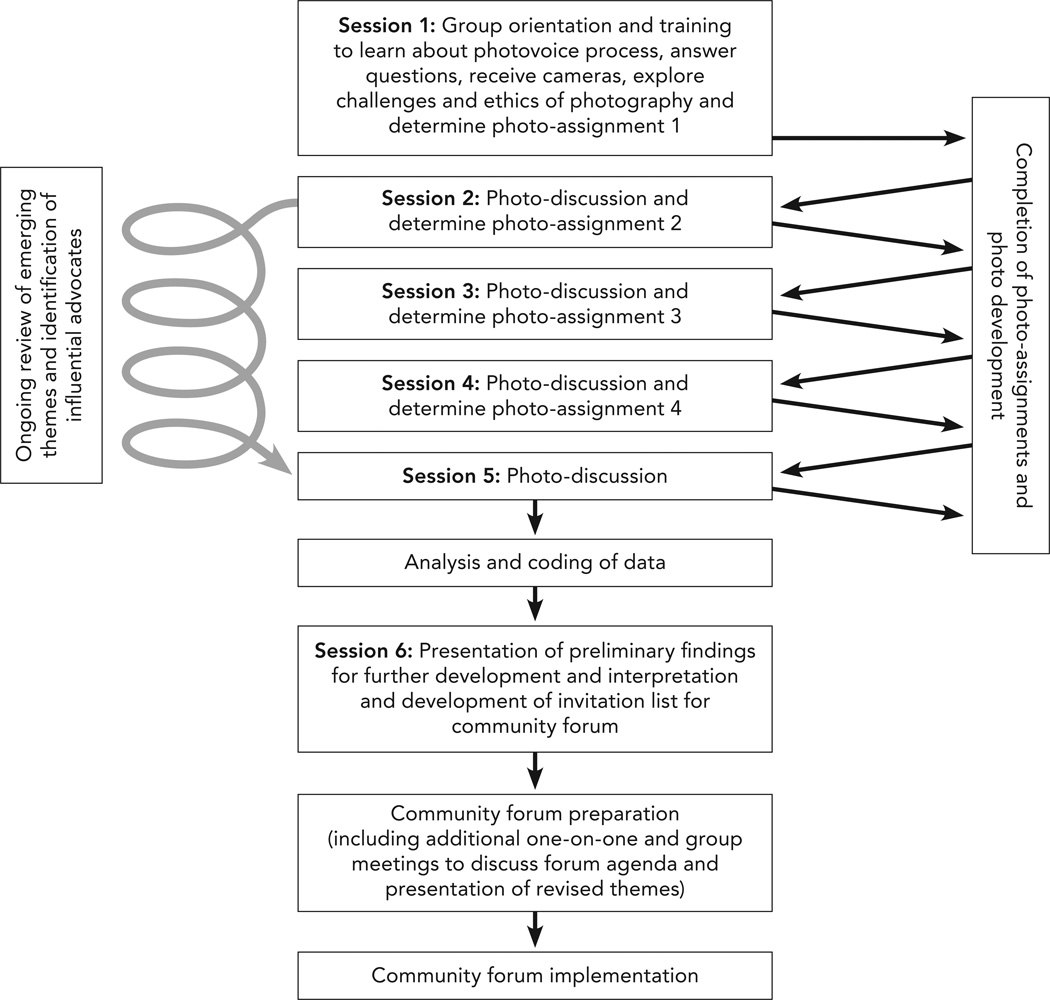

Typically participants in photovoice: (1) attend a group orientation and training session for them to learn about photovoice and its purpose, receive disposable cameras, explore the challenges and ethics of photography, and determine the assignment for the first of three to seven photo-assignments; (2) record through photography the realities of their experiences for each photo-assignment for one to two weeks; (3) participate in group photo-discussion sessions in which photographs from each photo-assignment served as triggers for discussion to examine needs, challenges, assets, and priorities, and identify potential solutions to effect change; (4) organize a forum to present their photographs and the identified priorities to local community members and leaders, policymakers, service providers, and other “influential advocates” who may be potential collaborators, partners, and advocates for change (including those with power and/or resources to support action; Hergenrather et al., 2009; Lopez, Eng, Randall-David, & Robinson, 2005; Rhodes, Hergenrather, Wilkin, & Jolly, 2008). Examples of actions resulting from photovoice have included working to meet the treatment and prevention needs of substance users and those at risk for substance use and relapse within a high risk community (Rhodes et al., 2008), reaching policy makers to address women’s health needs in China (Wang, Burris, & Ping, 1996), and securing health services in an immigrant-receiving urban neighborhood in Canada (Haque & Eng, 2011).

Photo-discussions begin with a review and discussion of themes that emerged from the previous photo-discussions, followed by a “show-and-tell” activity in which participants present their photographs based on the photo-assignment decided upon during the previous photo-discussion. After the “show-and-tell” portion of the photo-discussion, the discussion becomes more structured through the use of six key questions linked by the mnemonic “SHOWED” (Hergenrather et al., 2009; Wang & Burris, 1997). These questions are designed to move from concrete observations about the photographs to abstract critical analysis and action (i.e., “What do you See in the photo?” “What is really Happening here?” “How does this relate to Our lives?” “Why does this situation exist/orrur?” “How can we become Empowered to do something about it?” and “What can we Do about this situation?). Each participant is encouraged, but not required, to select one photograph relevant to the photo-assignment to share with the group. Although SHOWED or its Spanish-language equivalent VENCER (Baquero et al., 2014) is often used to guide the group photo-discussion of each photograph, we have found that a revised version, outlined in Table 1, of four as opposed to six triggers is more successful to move the discussion more quickly to action among Spanish-speaking, more recently arrived immigrant Latinos (Rhodes et al., 2009; Streng et al., 2004).

Table 1.

Empowerment-based photovoice triggers in English and Spanish used during photo-discussions

| English | Spanish |

|---|---|

| 1) What do you see in this photo? | 1) ¿Qué es lo que ves en la foto? |

| 2) How does this make you feel? | 1) ¿Cómo te hace sentir esto? |

| 3) What do you think about this? | 1) ¿Qué piensas sobre esto? |

| 4) What can we do about this? | 1) ¿Qué podemos hacer sobre esto? |

After the final group photo-discussion, the group typically continues to meet to work together to further refine findings and key themes and to organize and finalize a community forum, a key component of photovoice.

Setting and eligibility

This photovoice study took place between August 2012 and February 2013 in Durham and Wake counties in NC. Eligibility criteria included being 18 years old or older, being male-to-female transgender, self-identifying as Latina, speaking Spanish, being born outside of the US, and providing informed consent.

Participant recruitment, compensation, and protection

A convenience sample was used. A transgender woman who served as a lay health advisor (known as a “Navegante”) in the CBPR partnership’s study to test the efficacy of the HOLA intervention (Rhodes, Daniel, et al., 2013; Tanner et al., 2014) used word-of-mouth to recruit participants.

A two-hour introductory meeting was held for participants to discuss the photovoice process, ethics and safety in photography, and camera operation. Potential participants were advised that they would receive $50.00 cash for each session attended, a disposable camera for each photo-assignment, and one copy of each photograph taken, and that film remaining after taking the study-related photos could be used to take pictures of anything they wanted. A meal was served at each photovoice meeting.

Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study and provided human subject oversight. All participants reviewed and signed a Spanish-language consent form.

Measures

A short Spanish-language questionnaire collected demographics about participants, including age, self-identified race/ethnicity, country of origin, formal educational attainment, number of years/months since arrival in US, and employment status.

Photo-assignments for each of the photo-discussions were decided upon by the participants as a group, not by the academic researcher partners. However, participants did not always agree on each photo-assignment. A total of seven photo-assignments were conducted; they were: loneliness, physical health, discrimination, before and after, how my life changed with transition, positive things about being transgender, mental health, and long- and short-term goals.

Photo-discussions and supplemental data analysis and community forum planning sessions were conducted usually in the evenings, were held in a convenient location, lasted approximately two to three hours, and were audio-recorded.

Two Spanish-language fluent facilitators led the photo-discussions and supplemental sessions. One facilitated the photo-discussions, and the other operated the audio-recorder, and collected and displayed the shared photographs, and took notes. One facilitator was a native Spanish-speaking gay man originally from Peru and the other was a non-Latina white non-transgender female fluent in Spanish.

During the photo-discussions, each participant shared up one photograph with the group through the facilitator-guided discussion based on the questions illustrated in Table 1. After the photo-discussion, the participants determined a topic for their next photo-assignment.

Data preparation, analysis, and interpretation

After each photo-discussion, the facilitators documented initial general impressions about the process and content. Next, they listened to the audio-recorded discussion and took general notes. The discussion was then transcribed in full detail into English by a professional transcriptionist.

After photo-discussions transcripts were verified, authors (an ad hoc committee of the partnership) completed an inductive interpretative process that included participant involvement in data analysis and interpretation. Grounded theory was used to generate theory that is based in the data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The analysis team used open coding which included exploring, examining, and organizing the transcript data into broad conceptual categories and refined codes within and across the transcripts using constant comparisons. Codes were reviewed to generate initial themes (Silverman, 2001).

Preliminary codes and themes were presented to participants throughout the photovoice process. This process was iterative with the authors providing analytic draft theme development and the participants revising, further developing, validating, approving, and interpreting these themes. These meetings were conducted until the participants felt that the findings were valid (depicting what they themselves experienced) and wanted others to understand about their lived experiences. Our process was not designed to quantify participant experiences; rather, we wanted to capture both the depth and breadth of experiences to lay a foundation for informed and meaningful next steps.

Community forum

In accordance with the conceptual foundation of photovoice that includes moving toward action in partnership with influential advocates (Hergenrather et al., 2009), revised themes and their interpretation were presented during a bilingual community forum to validate findings and develop recommendations to move knowledge generated to action. Objectives of the forum included: forum attendees learning about the needs, assets, and priorities of immigrant Latina transgender women; identifying how photovoice findings relate to their work; and brainstorming actions to better address the needs and priorities of Latina transgender women.

Participants and the authors worked together to develop the invitation list for the forum, which included friends and family of photovoice participants and other influential advocates known by participants and the CBPR partnership as working (paid and unpaid) in community health including primary care, mental health, and transgender health; immigration policy and civil rights; law enforcement; local Spanish-language media; and other service provision. This approach is based in Freirean community organizing in which those with less formal power raise the consciousness of and build alliances with influential advocates, those who are potentially sympathetic power and resource holders who then can affect those to whom they have access (Freire, 1970, 1973; Rhodes et al., 2008). This progression continues, utilizing formal and informal networks with the ultimate goal of action and change.

The forum was held in Raleigh, NC, to allow easy access for attendees from across the state. The photovoice process, data analysis procedures, and findings and their interpretation were presented, and some of the participants shared their own stories that linked to the overall photovoice findings. Then forum attendees participated in a facilitated group discussion and brainstorming session. They divided into small groups to answer five primary questions, based on empowerment theory, that were designed to move from hearing and understanding the findings to promoting action: (1) What do you see in these findings? (2) In what ways do these findings make sense to you? (3) In what ways do these findings not make sense to you? (4) What can be done? / What can we all do? (5) What should we be doing to support transgender persons? These questions were successfully used by the CBPR partnership previously (Rhodes et al., 2011; Rhodes et al., 2008).

Each small group was asked to capture in bullet-point format on newsprint their responses to questions 4 and 5. Each group then presented the key points of their discussion and their recommendations to the entire forum. Next, a representative from the Center of Excellence for Transgender Health in Oakland, California, spoke about the potential to apply the Coalitions in Action for Transgender Community Health (CATCH) model in NC as a way to strengthen community responses to transgender health needs. The CATCH model is designed to guide a community mobilization to promote provider networking and community utilization of existing services (http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=programs-catch).

Figure 1 provides an overall stepwise guide of our photovoice process.

Figure 1.

The photovoice process

Results

Photovoice Participants

A total of nine Latina transgender women participated in photovoice. Mean age was 30, ranging from 22–45, years old. All participants self-identified as Latina; all reported being originally from Mexico. Mean number of years living in the US was 10, ranging from 4–16 years. Four participants reported having less than the equivalent of a high school diploma; the remaining five reported at least high school diploma or passing the general educational development (GED) test. Six of the nine participants reported full-time employment working in restaurants (n=4), cutting hair (n=1), and cleaning houses (n=1). The remaining three had part-time employment in a factory, as a cashier, and as a gardener. In terms of language spoken, one reported speaking only Spanish; four reported more Spanish than English; and four reported speaking both Spanish and English equally.

Qualitative Findings

Eleven themes emerged from our iterative, participatory process. These themes were organized into three main domains: (1) daily challenges; (2) needs and priorities; and (3) community strength and assets. Domains and themes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Qualitative domains and themes the emerged from photovoice with immigrant Latina transgender women

| 1) Daily challenges |

| Priority health risks |

| Uncertainty about the future |

| Discrimination and lack of sensitivity in society |

| Anxiety about family reaction |

| 2) Needs and priorities |

| Health and social services for transgender persons |

| Sources of emotional support for Latina transgender women and their families |

| Collective action |

| 3) Community strengths and assets |

| Psychosocial support from some family members and other Latina transgender women |

| Wisdom and survival strategies through lived experiences |

| Institutions supportive of Latina transgender women |

| Personal and professional goals |

1) Daily challenges

Priority health risks

Participants noted a variety of physical health issues of concern; however, two main health risks emerged as priorities. First, they reported ongoing unsafe hormone use. Because they had little access to formal health care due to lack of health insurance, few providers offering hormone therapy, and even fewer who provide bilingual, low-cost care, as examples, they relied on one another for advice about hormones (including dosage, timing, and side effects); guidance on how to acquire hormones from non-medical sources; and administration of hormones. Participants acknowledged that using hormones without medical advice and oversight was risky, but they felt they had no other options because they could not afford health insurance and were unaware of health care options for transgender persons. Participants also noted that some transgender women may rely on non-medical sources, not merely because of cost, but because they assume that they might get faster results bypassing more conservative formal health care; for example, they reported that they assumed that increasing hormone dosage would help them get the results they wanted more rapidly. Participants noted that sometimes substances were misused, such as mineral oil injected to enhance or soften features.

Second, participants also reported engaging in unsafe coping strategies. These included alcohol and drug use and abuse and unsafe sex. They reported that that these behaviors were used to relieve loneliness and stress.

Uncertainty about the future

Participants expressed concerns about their careers, the possibility for creation of families, and their potential return to their communities of origin in Mexico. They worried about whether they would be discriminated against if others at their workplaces realized they were transgender, not getting promoted and being required to work less desirable hours, and which bathrooms to use at work.

Participants reported worrying about whether they would be able to find a partner who truly accepted them. Participants talked about how they believed that having children was a dream they gave up when they began their transition, and a participant reported that she assumed that her current partner of several years would leave her when he decided he wanted children.

Many participants hoped to return to Mexico to their communities of origin but wondered about what life would be like with their new gender identity. Most participants reported transitioning after they arrived in the US and thus worried about being accepted by family and friends in Mexico, where they felt the stigma around gender identity was even greater.

Representing both unhealthy coping and uncertainty about the future, a participant noted,

“When I feel lonely… when I feel really bad and I wonder how my life will end up… I will start driving and I think about if I am going to crash into something or not… and I don’t care where I go… I cry and I think about how my life is going to end up… that is what I am scared of… I have seen many [of us] who are young and end up dead…and I don’t want to end up like [them].”

Discrimination and lack of sensitivity in society

Participants described multiple daily experiences of discrimination and insensitivity. They described differential treatment at their workplaces by employers and co-workers and disrespect from individuals working in the businesses they patronize, including restaurants, stores, and auto mechanics. They also described generalized disregard and even hatred, as a participant described, “I was looking for a parking space… and a woman started saying to me ‘You should not exist, Jesus doesn’t love you.’ I felt very embarrassed and so I left.”

Some participants also reported negative experiences with law enforcement. For example, a participant described how she was a victim of intimate partner violence in a public space. However, when the police officers who had been called learned of her gender identity, they were disrespectful and discriminatory, did not help her, and told her and her partner to go home; in effect, she was told by police to go home with the perpetrator.

Finally, participants described humiliating experiences being referred to by their former names in agencies that they used for needed services. An example of this disrespect was treatment that participants reported that they had received at the Mexican Consulate in Raleigh, NC. Participants went to the Consulate for needed services including documentation, passports, and visas; legal advice and support; and health promotion and disease prevention services; however, participants reported some frontline staff reacted disapprovingly, refusing to use their preferred female names and requiring gender expression for photographs on passport and visa renewals to reflect the gender documented on official birth certificates or passports, rather than the participants’ current gender expression.

Anxiety about family reaction

Participants reported a high level of anxiety related to their families’ reaction to their gender identity and expression. Some participants noted that they had experienced rejection by relatives. Even among family members who had accepted them, the understanding and acceptance process was gradual and took time. Moreover, participants noted that their families were stigmatized by members of the community based on participants’ transgender identity further complicating relationships between participants and their families; families were hurt by what others thought of them and their transgender relative.

2) Needs and priorities

Health and social services for transgender persons

Participants identified several needs including: the need for transgender-inviting and friendly clinical spaces; creation of standard protocols and/or training at agencies where transgender persons access services (including health departments, hospitals, and the Mexican Consulate); health professionals with the requisite knowledge to provide state-of-the-science care (e.g., appropriate use of hormones); access to care that is affordable; and transgender-specific information in Spanish. As a participant noted,

“There should be space for us, where we can feel comfortable, where there is a person that is specialized in people like us, where you can go and feel secure and that person knows what you are and isn’t going to treat you rudely… The best solution for our community would be a place where we can get information and all of that.”

Furthermore, participants wanted access to services about legal issues including workplace discrimination and options for having and adopting children. Finally, participants noted the complexity of interpersonal relationships and the risks some transgender persons may take or be forced to take and thought that more work in terms of understanding the context of sexual risk; intervening on risk; and promoting sexual health was needed. Participants suggested that the stigma associated with being transgender affected sexual health and required more understanding, appreciation and sensitivity, and intervention at multiple levels. Although participants reported a need for individual-level support, they also acknowledged the need for community change to reduce misunderstanding and stigma that resulted in their reduced sexual health.

Sources for emotional support for Latina transgender women and their families

Participants noted the need for greater psychosocial support. They found it difficult to identify individuals in their community to trust and confide in and from whom they can obtain meaningful support. They also shared that their families also need information and education about gender identity and counseling about understanding, accepting, and supporting transgender family and community members. A participant illustrated the need for support for both transgender Latinas and their families by sharing,

“Sometimes when I feel sad, I think about the things that happened to me when I was younger, and I think a lot about the family that turns their back on you when you most need them. The truth is that I would like my mother to accept me, and I want her to know everything that I am going through because I don’t have her support.”

Collective action

Participants reported that collective action among transgender Latinas is needed to demand equal rights and create change. They were committed to learning from other marginalized groups that organized to develop and push a social justice agenda. Participants cited the immigrant rights movement as an example of such community organizing that was familiar and relevant to them as immigrants.

3) Community strengths and assets

Although a number of challenges and needs were identified, participants also highlighted four key existing community strengths and assets.

Psychosocial support from some family members and other Latina transgender women

Participants noted that although most family members were not accepting of their gender identity, family members who were accepting provided profound levels of psychosocial support, emotional stability, and sense of self-worth. They also recognized the social support that they received from other transgender women who had been through similar experiences, particularly as they transitioned from male to female gender expression. This support included emotional (e.g., encouragement, concern, empathy, and acceptance), tangible (e.g., services), informational (e.g., advice, guidance, and problem solving) and companionship (e.g., belonging) support.

Wisdom and survival strategies through lived experiences

Participants described how their increasing wisdom, resilience, and resourcefulness increased as they overcame the challenges they faced as immigrant Latina transgender women. They reported finding strength and beauty in solitude; better determining when and how to effectively react to discrimination; and being more conscious of their appearance and attire (e.g., dressing as a professional woman for work). They also reported being more aware of the impact of their decisions and thus being more prepared for positive and negative outcomes. For example, a participant noted how her physical appearance and choice in attire may affect an interaction when accessing a service provider.

Institutions supportive of Latina transgender women

Several participants reported that their employers provide key opportunities for advancement regardless of gender identity. Moreover, although participants rarely accessed health care due to cost and lack of insurance, the few times that some participants reported seeing a provider, their experiences were “mostly positive”, including providers who were respectful (e.g., using preferred names and pronouns and asking questions for clarification) even when they did not have expertise in transgender health. Thus, participants reported that most providers have both the willingness and the potential to provide good care.

Personal and professional goals

Participants noted that their goals were important to them and provide them with “positive things to focus on” in a world that at times can be overwhelmingly unaccepting and discriminatory. Goals were identified as providing focus and the motivation to overcome adversity, gain self-respect and respect from others, and feel fulfilled. Goals discussed included increasing their education, advancing their career, and starting a family, in spite of added challenges related to their gender identity. As a participant shared,

“Now, I have different goals and now it’s not about doing shows [at clubs]. Before, I used to think that I would become famous doing [lip syncing performance and “drag”] shows and be on TV. Right now, I have a project that I know is going to bring in more than the shows. It’s a nutrition center. That was a goal that I had and, thank God, I accomplished it and now I have other goals as well.”

Community Forum-Identified Actions

Community forum attendees (N=60) included representatives from the lay community, community-based organizations (including Latino-serving and advocacy organizations), law enforcement, community health clinics (e.g., Planned Parenthood, Inc.), mental health providers, AIDS service organizations, the NC Mexican Consulate, Spanish-language media, and academic research institutions. Forum attendees were racially/ethnically diverse and included transgender persons, males, and females.

After reviewing the photovoice findings and engaging in facilitated discussion using the questions outlined in the methods section designed to increase understanding and promote action, forum attendees identified ten actions to positively affect the lives of immigrant Latina transgender women both in the short and long term. Table 3 provides a description of these actions organized into: community- and policy-level; agency-level, and individual-level actions. There were no priority actions; rather, attendees identified actions and committed to next steps in which they may have some power. As examples, to respond to action 2, (Advocacy; Table 3), a representative from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) committed to exploring into the process for asylum seeking for undocumented Latina transgender persons and determining how the ACLU could help. To respond to action 4 (Education for agency staff; Table 3), photovoice participants who spoke at the forum offered to serve as resources to help to develop and implement sensitivity or cultural competency training curricula for staff at local agencies to ensure that education about how to better serve the Latina transgender community is based on the lived experiences of community members. To respond to action 5 (Outreach to the Latina transgender community; Table 3), a representative from Planned Parenthood planned to work with agency leadership to expand their agency’s outreach to Latina transgender women.

Table 3.

Actions identified at the community forum

Community- and policy-level actions

|

Agency-level actions

|

Individual-level actions

|

Discussion

This study built a partnership among Latina transgender women and members of a CBPR partnership and obtained rich qualitative insight into some of the needs, assets, and priorities of Latina transgender women within a region of the US that is considered to be a new destination for immigrant Latinos (US Census Bureau, 2014) and has less favorable attitudes about immigration (Gill, 2010; Rhodes et al., 2015; Streng et al., 2004; Vissman et al., 2011) and gender and sexual diversity (Herek & McLemore, 2013; Norton & Herek; Weakliem & Biggert, 1999) than other parts of the country. The participatory nature of the project supported participants as they identified, described, and discussed important aspects of their lives as immigrants, as Latinas, and as transgender women; and defined actions that could be taken. From the participants’ photographs and discussions emerged contextual descriptions of the needs, assets, and priorities of immigrant Latina transgender women. The community forum offered attendees the opportunity to learn from immigrant Latina transgender women about their lives through presentations of photographs, qualitative themes, and their own stories. It also facilitated a process to move this new understanding to positive and supportive action.

Participants described daily challenges that they faced which included physical health risks related to gender transitioning and maintenance; psychosocial risks related to unsafe coping strategies, including alcohol and drug use and unsafe sex, worries about the future, and anxiety related to their families’ rejection; and discrimination. They also identified needs and priorities, including increased supportive and culturally congruent health, psychosocial, and legal services, and sexual health promotion efforts. Overall, transgender persons are disproportionately affected by HIV and STIs (Poteat, Reisner, & Radix, 2014) and within this group of transgender women HIV and STIs were concerns, but like other members of neglected and vulnerable communities, their needs and priorities were broad, well beyond HIV and STIs. HIV and STI prevention interventions must reach beyond condom use and address psychosocial and legal determinants affecting risk among immigrant Latina transgender women.

Noteworthy was the finding that participants reported that collective action was important. They did not “expect” others to meet their needs; they wanted to partner and push for the changes that they saw as necessary and just. They wanted to be part of a social justice movement. In fact, seven participants took the podium during the forum and shared their stories. They knew the power of putting a face to the data in order to organize and mobilize to motivate action.

Participants noted community strengths and assets that included supportive family members and other Latina transgender women, and the wisdom that comes from life experience. They also noted that having personal and professional goals helped them cope with challenges they faced.

Community forum

Attendees at the community forum identified priorities designed to increase awareness of the needs, assets, and priorities of immigrant Latina transgender women. A crucial component of increased education was the inclusion of Latina transgender women in creating change within the general community through their involvement in the development of sensitivity training curricula to reduce stigma faced by Latina transgender women.

Subsequent to the forum, new partnerships developed between participants and agencies. Staff from a local Planned Parenthood, for example, met with participants to provide information about their programs, including programs designed to provide transgender women with access to formal medical care for their hormone use. Participants also visited another community health clinic and staff from the clinic ultimately revised their sliding fee scale to help ensure access to safe hormone therapy among Latina transgender women.

Lessons learned

Key to the photovoice process was building trust; this was particularly crucial for participants with intersecting and often stigmatized identities (e.g., being Latina, being an immigrant, having varying documentation statuses, and self-identifying as female and/or as transgender). Overall, we found that participants developed a high level of interest and commitment to, and pride in, the project. The facilitators were crucial to trust building. Participants were not accustomed to engaging with outsiders who were sincerely interested in their stories. However, the multiple sessions of photovoice built trust because the facilitators came back repeatedly, illustrating that the facilitators were committed, and with actual drafts of emerging preliminary themes from each photo-discussion to review. This process illustrated that the facilitators were listening to participants and engaged in a collaborative co-learning process. Furthermore, the action orientation of photovoice showed participants that the facilitators were not merely “studying” them, but that they were committed to helping improve the health and well-being of participants.

The logistics of photovoice were challenging and required much flexibility on the part of the facilitators. Cameras were collected between photo-discussions for developing which required multiple telephone calls and text messages to confirm meetings, and some participants needed rides to photo-discussions. At the time of this project, NC Department of Motor Vehicles had not issued driver’s licenses to anyone without social security numbers since 2006 (Rhodes et al., 2015).

Furthermore, there is much discussion about the importance of skills development among vulnerable populations as an approach to health disparities reduction (Institute of Medicine, 2003, 2011). Participants in this project developed skills in leadership, public speaking, partnership development, harnessing relationships with media, negotiation and group-decision making, and community engagement, organization, and mobilization.

Limitations

Participant selection was based on a small convenience sample of immigrant Latina transgender women ages 18 and above and, therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to all Latina transgender women generally or within this region specifically. However, for the purposes of formative research, the findings from this study may inform the identification and development of resources to meet the needs of transgender women from similar communities and backgrounds. Further research using alternate data collection methodologies, such as individual in-depth interviews and venue-based intercept assessments, may provide further data and insights into the needs, assets, and priorities of immigrant Latina transgender women in the Southeast.

Conclusions

Since this project, some participants have left NC; the immigration policy enforcement environment in the state continues to worsen, and some participants have identified more supportive communities (e.g, San Francisco, California) that also provide expertise for those seeking asylum based on gender identity. Work with CATCH has not yet progressed due in part to the lack of readiness of the state; however, it is important to remember that seeds that were planted during the project may be germinating. Our partnership used a similar community forum format to present qualitative data on HIV prevention among African American, Latino, and white MSM and to facilitate the development of potential actions; actions that were identified during that forum and have since occurred as a result of the process include redirection of NC prevention funds to develop MSM safe spaces throughout NC for facilitated supportive men’s group dialogue around issues of masculinity and intimacy; a statewide conference to develop community organizing and advocacy skills among formal and informal MSM community leaders; and a new research partnership to explore the role of immigration policy on public health service utilization among immigrant Latinos (Rhodes et al., 2011). Thus, in time, further steps, such as those identified at the community forum that was the culmination of this photovoice project, may be taken to address the needs, assets, and priorities of immigrant Latino transgender women in NC.

Overall, photovoice served as a vehicle for images and words to express the concerns of immigrant Latina transgender women to local leaders and agencies that could potentially be partners in addressing concerns. This process helped identify not only needs and priorities but also assets that could be leveraged to improve the lives of members within this community.

Contributor Information

Scott D. Rhodes, Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Jorge Alonzo, Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Lilli Mann, Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Florence Simán, El Pueblo, Inc, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Manuel Garcia, Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Claire Abraham, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Christina J. Sun, Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

References

- Baquero B, Goldman SN, Simán F, Muqueeth S, Eng E, Rhodes SD. Mi Cuerpo, Nuestro Responsabilidad: Using Photovoice to describe the assets and barriers to reproductive health among Latinos. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 2014;7(1):65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan M, Galvan F. Perceived discrimination and depression among low-income Latina male-to-female transgender women. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:663. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Herder and Herder; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York, NY: Seabury Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Gill H. The Latino Migration Experience in North Carolina: New Roots in the Old North State. Chapel HIll, NC: University of North Carolina; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AR, Meyer IH. Gender nonconformity as a target of prejudice, discrimination, and violence against LGB individuals. J LGBT Health Res. 2007;3(3):55–71. doi: 10.1080/15574090802093562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Herman JL, Harrison J, Keisling M. National Transgender Discrimination Survey Report on Health and Health Care. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Krueter M, Krueter MW. Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Environmental Approach. 3. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Haque N, Eng B. Tackling inequity through a photovoice project on the social determinants of health: Translating Photovoice evidence to community action. Glob Health Promot. 2011;18(1):16–19. doi: 10.1177/1757975910393165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, McLemore KA. Sexual prejudice. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:309–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrather KC, Rhodes SD, Cowan CA, Bardhoshi G, Pula S. Photovoice as community-based participatory research: a qualitative review. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(6):686–698. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.6.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwahng SJ, Nuttbrock L. Adolescent gender-related abuse, androphilia, and HIV risk among transfeminine people of color in New York City. J Homosex. 2014;61(5):691–713. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2014.870439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger P, Kovacs S, Anderson-Smits C, Schmidt N, Salinas O, Hembling J, Shedlin M. Patterns and predictors of HIV/STI risk among Latino migrant men in a new receiving community. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):199–213. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9945-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez ED, Eng E, Randall-David E, Robinson N. Quality-of-life concerns of African American breast cancer survivors within rural North Carolina: Blending the techniques of photovoice and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(1):99–115. doi: 10.1177/1049732304270766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Capoferro C. The geographic diversification of American immigration. In: Massey DS, editor. New Faces in New Places. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008. pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow RA, Brown DD. Critical Theory and Methodology. Vol. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Norton AT, Herek GM. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward transgender people: Findings from a national probability sample of U.S. adults. Sex Roles. 2013;68(11–12):738–753. [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Hwahng S, Mason M, Macri M, Becker J. Gender abuse, depressive symptoms, and HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among male-to-female transgender persons: a three-year prospective study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):300–307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock L, Hwahng S, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Mason M, Macri M, Becker J. Lifetime risk factors for HIV/sexually transmitted infections among male-to-female transgender persons. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(3):417–421. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab6ed8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock L, Hwahng S, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Mason M, Macri M, Becker J. Psychiatric impact of gender-related abuse across the life course of male-to-female transgender persons. J Sex Res. 2010;47(1):12–23. doi: 10.1080/00224490903062258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter TM. Connecting the dots: When the risks of HIV/STD infection appear high but the burden of infection is not known - The case of male Latino migrants in the Southern United States. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(2):213–226. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto RM, Melendez RM, Spector AY. Male-to-female transgender individuals building social support and capital from within a gender-focused network. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2008;20(3):203–220. doi: 10.1080/10538720802235179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat T, Reisner SL, Radix A. HIV epidemics among transgender women. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9(2):168–173. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reback CJ, Fletcher JB. HIV prevalence, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors among transgender women recruited through outreach. AIDS Behav. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0657-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD. Demonstrated effectiveness and potential of CBPR for preventing HIV in Latino populations. In: Organista KC, editor. HIV Prevention with Latinos: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York, NY: Oxford; 2012. pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Daniel J, Alonzo J, Duck S, Garcia M, Downs M, Marsiglia FF. A systematic community-based participatory approach to refining an evidence-based community-level intervention: The HOLA intervention for Latino men who have sex with men. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(4):607–616. doi: 10.1177/1524839912462391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Duck S, Alonzo J, Daniel J, Aronson RE. Using community-based participatory research to prevent HIV disparities: Assumptions and opportunities identified by The Latino Partnership. J Acquire Immuno Defic Syn. 2013;63(Supplement 1):S32–S35. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182920015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Eng E, Hergenrather KC, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Montano J, Alegria-Ortega J. Exploring Latino men’s HIV risk using community-based participatory research. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(2):146–158. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Aronson RE, Bloom FR, Felizzola J, Wolfson M, McGuire J. Latino men who have sex with men and HIV in the rural south-eastern USA: findings from ethnographic in-depth interviews. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12(7):797–812. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.492432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Griffith D, Yee LJ, Zometa CS, Montaño JTVA. Sexual and alcohol use behaviours of Latino men in the south-eastern USA. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2009;11(1):17–34. doi: 10.1080/13691050802488405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Vissman AT, Stowers J, Davis AB, Hannah A, Marsiglia FF. Boys must be men, and men must have sex with women: A qualitative CBPR study to explore sexual risk among African American, Latino, and white gay men and MSM. Am J Mens Health. 2011;5(2):140–151. doi: 10.1177/1557988310366298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Wilkin AM, Jolly C. Visions and Voices: Indigent persons living With HIV in the southern United States use photovoice to create knowledge, develop partnerships, and take action. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9(2):159–169. doi: 10.1177/1524839906293829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Mann L, Alonzo J, Downs M, Abraham C, Miller C, Reboussin BA. CBPR to prevent HIV within ethnic, sexual, and gender minority communities: Successes with long-term sustainability. In: Rhodes SD, editor. Innovations in HIV Prevention Research and Practice through Community Engagement. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 135–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Mann L, Simán FM, Song E, Alonzo J, Downs M, Hall MA. Identifying the impact of immigration enforcement policies by local officials on access to care among Latinos. Am J Public Health. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, McCoy TP. Condom use among immigrant Latino sexual minorities: Multilevel analysis after respondent-driven sampling. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2015;27(1) doi: 10.1521/aeap.2015.27.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, McCoy TP, Hergenrather KC, Vissman AT, Wolfson M, Alonzo J, Eng E. Prevalence estimates of health risk behaviors of immigrant Latino men who have sex with men. J Rural Health. 2012;28(1):73–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman D. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction. London: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag S. On Photography. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Southern AIDS Coalition. Southern States Manifesto: Update 2012. Policy Brief and Recommendations. Birmingham, AL: Southern AIDS Coalition; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Streng JM, Rhodes SD, Ayala GX, Eng E, Arceo R, Phipps S. Realidad Latina: Latino adolescents, their school, and a university use photovoice to examine and address the influence of immigration. J Interprof Care. 2004;18(4):403–415. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner AE, Reboussin BA, Mann L, Ma A, Song E, Alonzo J, Rhodes SD. Factors influencing healthcare access perceptions and care-seeking behaviors of Latino sexual minority men and transgender individuals: HOLA intervention baseline findings. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved2. 2014;5(4):1679–1697. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. [Accessed February 18, 2014]; Available at: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb08-123.html.

- Vissman AT, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Bachmann LH, Montaño J, Topmiller M, Rhodes SD. Exploring the use of nonmedical sources of prescription drugs among immigrant Latinos in the rural southeastern USA. J Rural Health. 2011;27(2):159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(3):369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA, Ping XY. Chinese village women as visual anthropologists: a participatory approach to reaching policymakers. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42(10):1391–1400. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weakliem DL, Biggert R. Religion and political opinion in the contemporary United States. Social Forces. 1999;77(3):863–886. [Google Scholar]