Abstract

Proper vascularization remains critical to the clinical application of engineered tissues. To engineer microvessels in vitro, we and others have delivered endothelial cells through preformed channels into patterned extracellular matrix-based gels. This approach has been limited by the size of endothelial cells in suspension, and results in plugging of channels below ~30 μm in diameter. Here, we examine physical and chemical signals that can augment direct seeding, with the aim of rapidly vascularizing capillary-scale channels. By studying tapered microchannels in type I collagen gels under various conditions, we establish that stiff scaffolds, forward pressure, and elevated cyclic AMP levels promote endothelial stability and that reverse pressure promotes endothelial migration. We applied these results to uniform 20-μm-diameter channels and optimized the magnitudes of pressure, flow, and shear stress to best support endothelial migration and vascular stability. This vascularization strategy is able to form millimeter-long perfusable capillaries within three days. Our results indicate how to manipulate the physical and chemical environment to promote rapid vascularization of capillary-scale channels within type I collagen gels.

Keywords: microvascular tissue engineering, collagen, endothelial cells, genipin, cyclic AMP, pressure

INTRODUCTION

A major goal in tissue engineering is the creation of microvessels (capillaries, arterioles, and venules) that can transport blood-borne solutes and cells throughout engineered constructs.1, 16 To date, most methods for forming functional microvascular networks use growth factor-induced angiogenesis and/or vasculogenesis.5, 11, 19, 20 Growth factor concentrations, endothelial and stromal cell densities, and extracellular matrix (ECM) composition influence the morphology of the resulting networks.34 Despite the ability of these methods to form perfusable, durable microvessels11, 13, 15, the methods are slow and provide limited control over the resulting vascular architecture. For instance, the self-organization of endothelial cells into perfusable networks within a fibrin matrix typically requires a week or longer.20 Methods that rely on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced vascular formation may not be ideal for uniform perfusion throughout a tissue because VEGF-based methods tend to yield leaky and disorganized networks.25

An alternate approach for vascularization is the direct seeding of patterned, microfluidic biomaterials with endothelial cells.3, 7, 18, 21, 35 In this approach, the scaffold is patterned by lithographic or other techniques so that it contains microfluidic channels, which are then seeded with cells. By design, this method provides precise control over vascular geometry, because the vessels form only along the original channels. Direct seeding of endothelial cells into microfluidic gels can result in the formation of confluent endothelial tubes in 1-2 days, with vessel lengths of 1 cm or more.7, 36

Despite the recent emergence of direct seeding as a viable approach to vascularization, this strategy has yet to generate microvessels with outer diameter less than ~30 μm (“capillary-scale” vessels).7, 40 Direct seeding fails at this size scale because endothelial cells tend to clog channels during seeding when the diameter of the channel approaches the diameter of a single endothelial cell in suspension (~10-15 μm). For direct seeding to be a viable way to vascularize capillary-scale channels, it must be augmented by signals that promote rapid migration of endothelial cells along any unseeded segments of a channel.

In this work, we study how physical and chemical signals affect vascularization of directly seeded capillary-scale channels, in hopes of applying those signals to create microvessels that mimic human capillaries in size and function. Because endothelial cells migrate as a sheet against the direction of fluid flow (i.e., upstream)8, 22, we hypothesized that seeded cells that plugged a narrow channel would migrate to barren areas if flow was directed from barren to plugged regions. Because a cell-permeant analog of cyclic AMP (dibutyryl cAMP) improves the stability of large (~120-μm-diameter) engineered microvessels26, 38, we hypothesized that elevated levels of intracellular cAMP would likewise improve the stability of newly formed endothelium in narrow (≤30-μm-diameter) channels. Moreover, substratum stiffness is a strong controller of endothelial cell function4; in particular, stiff substrata promote vascular stability in ~120-μm-diameter channels6, and we expected the same to hold at the capillary scale. By optimizing these physical and chemical signals, we have developed a technique for rapid generation of perfusable “capillaries” with diameters as low as 20 μm in type I collagen gels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HDMECs) (lots 6011802.1 and 5062201.1; Promocell) were grown on gelatin-coated tissue culture plates. Cells were cultured in MCDB131 media (Caisson Labs) with supplements of 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 1% glutamine-penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen), 25 μg/mL endothelial cell growth supplement (Biomedical Technologies), 0.2 mM ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma), 2 U/mL heparin (Sigma), 1 μg/mL hydrocortisone (Sigma), and 80 μM dibutyryl cyclic AMP (db-cAMP; Sigma). Cells were routinely cultured under 5% CO2 at 37°C and passaged at a ratio of 1:4 using 0.005% trypsin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen). Cells were used up to passage eight.

Formation of Channels in Collagen Gels

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS; Dow Corning) chambers that contained a 1-mm-wide, 1-mm-deep indent were sterilized with 70% ethanol and treated with UV/ozone for fifteen minutes (Jelight). Each chamber was then placed face down on top of a glass coverslip and a stainless steel needle or glass pipette that served as a template for molding a channel of desired diameter and taper within collagen gel (Fig. 1A).

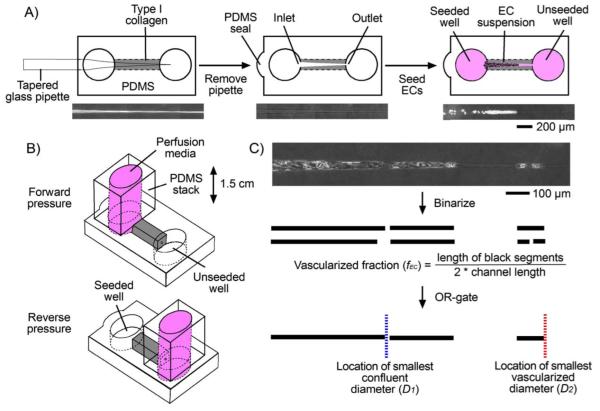

FIGURE 1.

Methods for the formation and analysis of seeded capillary-scale channels. (A) Gelling and seeding procedure, and corresponding phase-contrast images at each step. (B) Application of forward and reverse pressure, starting one day after seeding (“day 1”). (C) Vascularization metrics for seeded microchannels.

For uniform (i.e., not tapered) channels, we used 120-μm-diameter stainless steel needles (Health Point Products) or 60-μm-diameter needles that were formed by etching in nickel-based solution (Transene) for six minutes at 50°C. Uniform 120- and 60-μm-diameter channels were molded in 2-mm-long PDMS chambers.

For tapered channels, we used glass pipettes (0.58 mm inner diameter, 1 mm outer diameter; World Precision Instruments) that were pulled to a final diameter of 5 μm and a taper slope of ~10 or ~25 μm/mm on a P-97 pipette puller (Sutter). Channels were molded in 1- or 5-mm-long PDMS chambers.

All needles and pipettes were first sterilized with 70% ethanol and then immersed in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Calbiochem) for one hour at 23°C to reduce adhesion to subsequently formed gels.30

Rat tail type I collagen (final concentration of 7 mg/mL in PBS; BD Biosciences) was gelled around needles or pipettes for one hour at 37°C. PBS was added to the chamber wells after twenty minutes to maintain hydration. Removal of needles or pipettes yielded bare channels with desired diameters and taper. Channels were then crosslinked by perfusion with 20 mM genipin (Wako Biosciences) for two hours, flushed with PBS for four hours to remove residual genipin, and conditioned for at least eight hours with cell culture media that was supplemented with 3% 70 kDa dextran (Sigma). Some channels were not crosslinked, and instead were only conditioned with dextran-supplemented media. Dextran was included in the culture media to promote vascular stability.14

Diameters of unseeded channels were measured on day 0, and the collagen gels did not swell measurably over time.

Vascularization of Channels in Collagen Gels

Collagen channels were seeded by adding a suspension of HDMECs (~4×107 cells/mL) in dextran-supplemented media to one end (for uniform channels) or to the wider end (for tapered channels) (Fig. 1A). Channels were subjected to low flow (~0.25 μL/hr) for one day at 37°C in the reverse direction to remove nonadherent cells. One day after seeding (“day 1”), positive hydrostatic pressure was applied to the seeded well (“forward” pressure) or to the unseeded one (“reverse” pressure); the opposite well was left at 0 cm H2O (Fig. 1B). Flow rates were measured daily. Media consisted of dextran-supplemented media, which normally contains 80 μM db-cAMP (“low-cAMP” media), or the same media with 400 μM db-cAMP and 20 μM phosphodiesterase inhibitor Ro-20-1724 (Calbiochem) (“high-cAMP” media). These two cAMP concentrations were chosen since they resulted in marked differences in phenotype and vascular stability of large (~120-μm-diameter) engineered microvessels.26, 38

To evaluate the limits of direct seeding, we subjected seeded 120-, 60-, 30-, and 15-μm-diameter channels (n = 16) to forward pressure of 1.5 cm H2O with low-cAMP media for three days (i.e., to day 4 post-seeding). To study the effects of pressure direction and cAMP levels on capillary-scale vascularization, we seeded and subjected tapered channels with a taper slope of ~25 μm/mm (n = 68) to forward or reverse pressure of 1.5 cm H2O with low- or high-cAMP media for three days. To study the effects of pressure magnitude on vascularization, we seeded (nearly) uniform 20-μm-diameter channels with a taper slope of ~10 μm/mm (n = 24), equilibrated them for two hours with high-cAMP media at 37°C under no flow, and subjected them to reverse pressure of up to 3 cm H2O with high-cAMP media for five days.

Quantification of Vascularization

We defined three metrics to quantify the extent of vascularization on days 1 and 4 post-seeding (Fig. 1C). Phase-contrast images of seeded channels were obtained through a Plan-Neo 10×/0.30 NA objective using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope that was equipped with an environmental chamber held at 37°C. Acquired images were corrected for non-uniform illumination with Axiovision ver. 4.5 (Zeiss). The region with a diameter of 10-40 μm was used for measurements. The upper and lower side profiles of each channel were binarized, with black or white denoting where endothelial cells were attached or not, respectively. “Vascularized fraction” (fEC) was defined as the ratio of the sum of black segment lengths to the sum of black and white segment lengths. “Smallest confluent diameter” (D1) was defined as the largest channel diameter at which neither the upper nor the lower side profile had an attached cell. “Smallest vascularized diameter” (D2) was defined as the smallest channel diameter at which a cell was attached to the upper and/or lower side profile. D1, D2, and fEC were measured on day 1 before perfusion conditions were applied and on day 4 after pressure was applied for three days. For ~20-μm-diameter channels, the change in axial position of smallest confluent diameter (D1) was recorded daily to determine “migration rate” (v) (μm/hr). Endothelial retraction distance (δEC) (μm) was measured as the final axial position of confluent endothelium minus the furthest axial position over the course of five days; a negative value for δEC indicates instability of confluent endothelium.

Viability and Patency Assays

To assess the viability of the endothelium, we perfused seeded channels with 50 μg/mL calcein AM (Invitrogen) and 10 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). To assess the patency of the endothelium, we perfused channels with media that contained 100 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated 10 kDa dextran (Invitrogen). Channels were perfused for 30-60 minutes under the same pressure and cAMP conditions tested experimentally. Fluorescence images were obtained with a Plan-Neo 10×/0.30 NA objective. Composite images were assembled in ImageJ ver. 1.43u (NIH) and Adobe Photoshop 6.0.

Mechanical Characterization of Solid Collagen Gels

Type I collagen was gelled within 5-mm-long PDMS chambers for one hour at 37°C to form solid gels. Some gels were crosslinked by interstitial flow of 20 mM genipin for two hours at 25°C, and then flushed extensively with PBS. The permeability was measured in untreated and crosslinked gels (n = 14). Darcy permeability was calculated as κ = QLη/AΔP, where Q is the daily flow rate of media at 37°C through the gel averaged over three days, L is the gel length (~5 mm), η is the viscosity of the media (~1.4 cP), A is the cross-sectional area of the gel (~1 mm2), and ΔP is the applied pressure difference (~1.5 cm H2O).

The elastic moduli of ~1-mm-thick, ~10-mm-diameter collagen gels were measured by indentation (n = 12).6 Gel disks were untreated or crosslinked with 20 mM genipin for two hours at 25°C, and then washed extensively with PBS. Stainless steel or aluminum spheres (Precision Balls) were placed on top of gels submerged in PBS. The depth of sphere indentation was measured after two hours. The system was modeled as Hertz contact between a deformable and incompressible material; indentation modulus is given by E = πR5/2(ρ-ρPBS)g/δ3/2, where R is the radius of the sphere, ρ and ρPBS are the densities of the spheres and PBS, g is 9.8 m/s2, and δ is the indentation depth.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical testing was performed using Prism ver. 6 (GraphPad). Darcy permeabilities, elastic moduli, smallest vascularized diameters, smallest confluent diameters, vascularized fractions, migration rates, retraction distances, flow rates, and shear stresses are presented as means ± SD. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine if sample distributions originate from the same distribution for vascularization metrics. Dunn’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test was used to compare vascularization metrics and flow rates across pressure directions and db-cAMP concentrations, and endothelial retraction distance across pressure categories. Mann-Whitney test was used to compare values with or without genipin treatment, or values measured on days 1 and 4 post-seeding. Spearman’s correlation test was used to analyze the trend between estimated shear stress and migration rate. Differences were considered to be statistically significant for p < 0.05; the reported p values are multiplicity adjusted.

RESULTS

Scaffold Characterization

Scaffold permeability and elastic modulus affect the stability of large (~120-μm-diameter) endothelial tubes.6, 32, 36 We thus expected these physical properties to play a similar role in capillary-scale vascularization. The Darcy permeabilities of untreated and crosslinked collagen gels were 0.0097 ± 0.0025 μm2, and 0.0097 ± 0.0031 μm2, respectively. Permeability was not significantly affected by crosslinking (p = 0.87), matching previous results.6 At these permeabilities, the pore size of the scaffolds is small enough to inhibit invasion of the gel by cells.7

The elastic moduli of solid collagen gels were measured by indentation.6 The elastic moduli of untreated and crosslinked gels were 263 ± 50 Pa, and 1326 ± 101 Pa, respectively. As predicted, genipin treatment increased the elastic modulus (p = 0.0022).

Capillary-Scale Channels in Collagen Gels do not Spontaneously Vascularize

As previously shown7, direct seeding of endothelial cells yielded confluent 120- and 60-μm-diameter endothelial tubes in one day. This formation occurred in the absence of applied pressure (i.e., no flow) and in native and crosslinked gels.

Typical revascularization protocols perfuse vascular networks of scaffolds under forward pressure (i.e., the resulting flow is in the same direction as initial seeding) and do not supplement perfusion media with db-cAMP23, 29. We mimicked these conditions by subjecting seeded channels to forward pressure and low-cAMP media for three days after seeding. Under the small levels of pressure used (~1.5 cm H2O), 120- and 60-μm-diameter endothelial tubes in native gels began to delaminate by day 4; in crosslinked gels, tubes of either size remained stable up to day 4 (Fig. 2A, 2B).

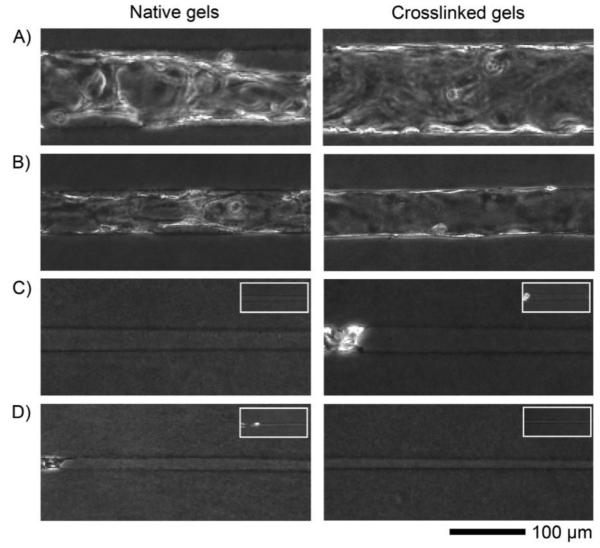

FIGURE 2.

Day 4 phase-contrast images of native and genipin-crosslinked collagen gels that were seeded and placed under forward pressure and low-cAMP media culture conditions. (A) 120-μm-diameter channels. (B) 60-μm-diameter channels. (C) 30-μm-diameter channels. (D) 15-μm-diameter channels. Insets show seeded channels on day 1. Seeding was from the left side.

Thirty- and 15-μm-diameter channels, however, did not spontaneously form confluent tubes. The 30-μm-diameter channels seeded unevenly, if at all (Fig. 2C, inset), while 15-μm-diameter channels effectively remained unseeded beyond the channel opening (Fig. 2D, inset). Moreover, in the sparsely seeded 30- and 15-μm-diameter channels, forward pressure and low-cAMP media did not promote vascularization by day 4, whether gels were crosslinked or not. Endothelial coverage remained low (<40%) in 30-μm-diameter channels, and flow rates through the channel often decreased as a “plug” of cells and debris developed at the distal end. Endothelial cells did not migrate along the barren regions of 15-μm-diameter channels.

Vascularization of Tapered Channels in Collagen Gels

To study how pressure and cAMP conditions affect vascularization, we used tapered type I collagen channels (slope of ~25 μm/mm). By design, the diameter of the channel decreased as the endothelial cells migrated beyond the point of seeding. This design allowed us to determine the smallest vascularized diameters as a function of culture conditions. One day after seeding (i.e., before pressure was applied), confluent vascularization occurred to regions of diameter D1 = 25.6 ± 5.4 μm, and patches of vascularization extended to diameter D2 = 17.7 ± 4.3 μm; total endothelial coverage (fEC) averaged 43.3% ± 15.0%. Seeding was sub-confluent in all tapered channels, with large barren patches often present. Crosslinking of gels with genipin was necessary for endothelial stability in tapered channels, as endothelium delaminated from untreated channels as early as two days after seeding.

To determine whether pressure direction or cAMP levels could improve capillary-scale vascularization, we cultured seeded channels for an additional three days under the following conditions:

1) forward pressure and low cAMP, 2) forward pressure and high cAMP, 3) reverse pressure and low cAMP, and 4) reverse pressure and high cAMP. Vascularization metrics were measured on day 4, by which the culture conditions resulted in unique vascularization profiles (Fig. 3 and 4):

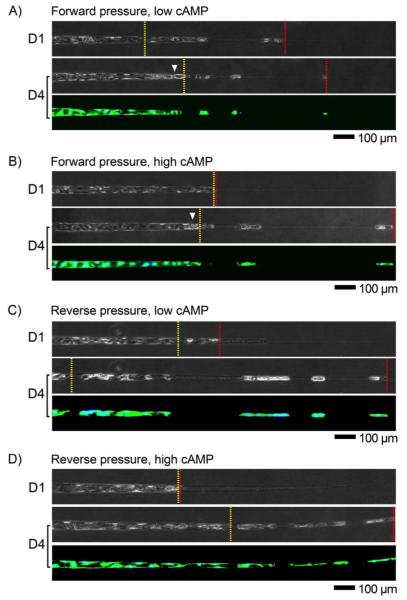

FIGURE 3.

Phase-contrast and fluorescence viability images of vessels that were cultured under various conditions, on days 1 and 4 after seeding. Displayed are regions with channel diameters between 10 and 40 μm. Locations of smallest confluent diameters are marked by yellow lines; locations of smallest vascularized diameters are marked by red lines. (A) Forward pressure and low cAMP. (B) Forward pressure and high cAMP. (C) Reverse pressure and low cAMP. (D) Reverse pressure and high cAMP. Arrowheads denote plugs. Seeding was from the left side.

i) Forward pressure and low cAMP

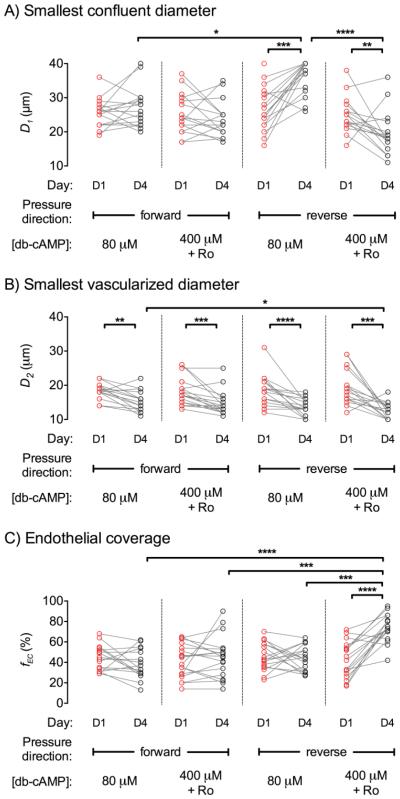

The addition of forward pressure and low-cAMP media on day 1 caused a “plug” of debris to form by day 4 (Fig. 3A). Plugs were located near the day 1 smallest confluent diameter, which implies that no significant migration of confluent endothelium occurred after day 1. Smallest confluent diameters (p = 0.38) and endothelial coverage (p = 0.15) did not differ between day 1 and day 4 (Fig. 4A, 4C). The smallest vascularized diameter decreased from day 1 to day 4 (p = 0.0024), as a result of single endothelial cells moving to narrower regions (Fig. 4B). Overall, the culture condition led to little change in the extent of vascularization by day 4.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of pressure direction and cAMP level on vascularization of tapered microchannels. (A) Smallest confluent diameter (D1) on days 1 and 4. (B) Smallest vascularized diameter (D2) on days 1 and 4. (C) Endothelial coverage (fEC) on days 1 and 4. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

ii) Forward pressure and high cAMP

Samples that were cultured under forward pressure and high-cAMP media largely exhibited the same phenotype as those under forward pressure and low-cAMP media (Fig. 3B). Again, a plug formed by day 4 near the day 1 smallest confluent diameter. Smallest confluent diameters (p = 0.15) and endothelial coverage (p = 0.90) did not change from day 1 to day 4; smallest vascularized diameter decreased from day 1 to day 4 (p = 0.0002) (Fig. 4).

iii) Reverse pressure and low cAMP

Reverse pressure and low-cAMP media did not result in formation of a plug, but resulted instead in endothelial delamination by day 4 (Fig. 3C). Smallest confluent diameter (p = 0.0001) increased from day 1 to day 4 (Fig. 4A), since the delamination was often severe enough to disrupt the continuity of endothelium. Smallest vascularized diameter (p < 0.0001) decreased from day 1 to day 4 (Fig. 4B). Although this culture condition promoted the distal migration of endothelial cells, it promoted delamination of already vascularized regions and the net effect was no significant change in endothelial coverage (p = 0.15) (Fig. 4C).

iv) Reverse pressure and high cAMP

Reverse pressure and high-cAMP culture did not result in a plug, and promoted migration and stabilized vascularized regions (Fig. 3D). From day 1 to day 4, smallest confluent diameter decreased (p = 0.0069), smallest vascularized diameter decreased (p = 0.0005), and endothelial coverage increased (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). On day 4, this culture condition resulted in smaller vascularized diameters compared to the forward pressure and low-cAMP culture (p = 0.018) and higher coverage than for the other three conditions (p < 0.001). Continuous vascularization occurred to regions of diameter D1 = 19.4 ± 6.3 μm, and patches of vascularization extended to diameter D2 = 12.4 ± 2.4 μm; total endothelial coverage (fEC) averaged 73.7% ± 13.3%. We note that reverse pressure and high-cAMP culture was not sufficient to form confluent vessels through the entire length of tapered channels, as endothelial coverage was below 100%.

Formation and Characterization of Perfusable ~20-μm-Diameter Vessels

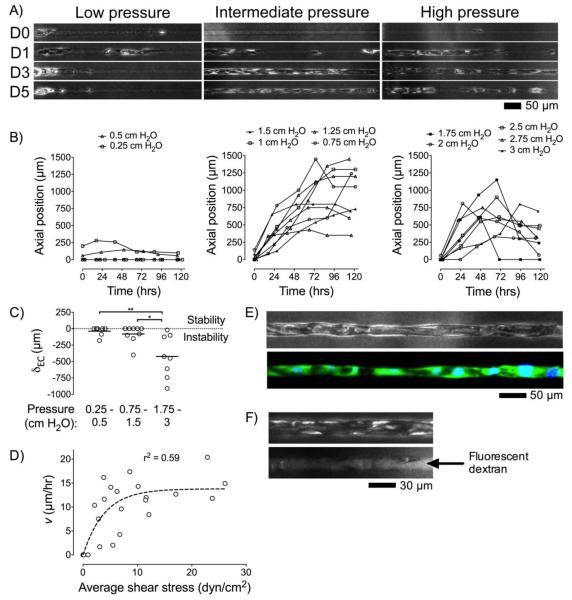

Based on our findings in tapered microchannels, we expected that it would be possible to make perfusable vessels from channels with diameters of ~20 μm by direct seeding of endothelial cells and application of optimized physical and chemical signals. Our results in tapered channels indicated the importance of collagen crosslinking, cAMP levels, and pressure direction for capillary-scale vascularization. Thus, 20-μm-diameter channels were crosslinked, seeded, and then cultured under reverse pressure and high cAMP. Genipin treatment and cAMP supplementation were necessary to form perfusable 20-μm-diameter vessels, as endothelium readily detached from the collagen wall without these stimuli. To determine whether pressure magnitude affects capillary-scale vascularization, we varied the pressure difference from 0.25 cm H2O to 3 cm H2O. We found that pressure magnitude modulated the migration profile of confluent endothelium along capillary-scale channels (Fig. 5):

FIGURE 5.

Vascularization of 20-μm-diameter channels. (A) Phase-contrast images (day 0, 1, 3, and 5) of seeded 20-μm-diameter channels cultured under high cAMP and low, intermediate, or high reverse pressure. (B) Migration profiles of confluent endothelium over five days for each pressure category: low (0.25-0.5 cm H2O), intermediate (0.75-1.5 cm H2O), high (1.75-3 cm H2O). (C) Retraction distance (δEC) of confluent endothelium for each pressure category. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. (D) Migration rate of confluent endothelium from day 0 to day 2 (v) versus average shear stress on days 1 and 2; fit was to a one-phase decay. (E) Phase-contrast and fluorescence images of a representative vessel cultured under intermediate reverse pressure for five days, then perfused with viability dyes. (F) Phase-contrast and fluorescence images of a representative vessel cultured under intermediate reverse pressure for five days, and then perfused with fluorescent dextran-containing media. Seeding was from the left side.

i) Low pressure (≤ 0.5 cm H2O)

Application of pressures of 0.5 cm H2O or lower did not support endothelial migration over the course of five days (Fig. 5A and 5B, left). This condition was unsuccessful in promoting vascularization, despite elevated levels of cAMP and a stiffened gel.

ii) Intermediate pressure (0.75-1.5 cm H2O)

Pressures between 0.75 cm H2O and 1.5 cm H2O supported rapid migration of endothelium along ~20-μm-diameter channels. For example, a representative sample under 1.25 cm H2O demonstrated migration of endothelium at ~17 μm/hr for three days until the channel was completely vascularized; endothelium remained stably attached to the collagen wall from day 3 through day 5 (Fig. 5A, middle). On average, the vascularization profiles under intermediate pressures had peak migration speed of v ≈ 12.5 μm/hr during the first two days of perfusion, until confluent endothelium reached the distal end of channels (Fig. 5B, middle). The success rate of complete vascularization of ~20-μm-diameter, 1-mm-long channels was ~50%.

iii) High pressure (≥ 1.75 cm H2O)

Pressures of at least 1.75 cm H2O also supported rapid migration of endothelium, at an average rate of v ≈ 12 μm/hr during the first two days of perfusion (Fig. 5B, right). Formation of stable vessels, however, did not occur since confluent endothelium exhibited widespread retraction by day 5 (Fig. 5A, right).

Thus, intermediate reverse pressures of 0.75-1.5 cm H2O best supported vessel formation within capillary-scale channels. Above a magnitude of ~1.5 cm H2O, reverse pressure led to significant endothelial retraction (δEC = -423 ± 323 μm) compared to intermediate pressures (p = 0.021) (Fig. 5C). Below a pressure of ~0.75 cm H2O, endothelial cells did not migrate along the channel.

To determine the viability and patency of these 20-μm-diameter “capillaries” under optimized pressure conditions, we perfused the vessels with viability indicators or fluorescent dextran-containing media on day 5, respectively. Channels cultured under intermediate reverse pressure resulted in vessels that contained viable endothelium (Fig. 5E) and open lumens (Fig. 5F).

DISCUSSION

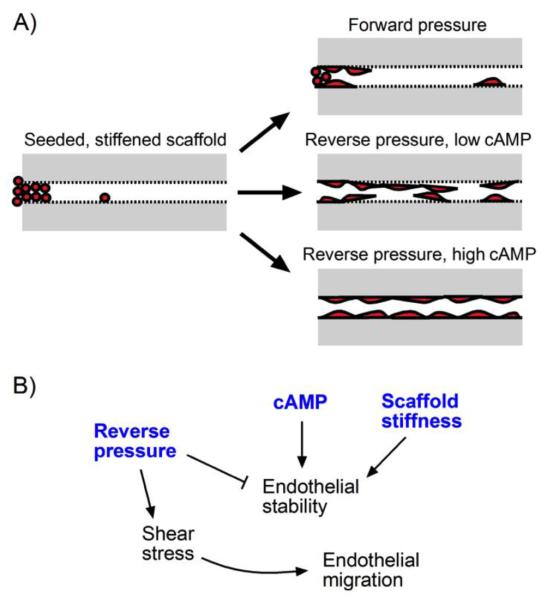

Vessels with diameter less than or equal to ~30 μm cannot be made reproducibly by directly seeding channels in type I collagen gels. Even when individual endothelial cells are smaller than the channel diameter, they can quickly plug the channel and do not spontaneously migrate to vascularize the region adjacent to the plug. Our results indicate that the combination of a stiff gel and culture under intermediate reverse pressure and high cAMP best promotes capillary-scale vascularization (Fig. 6). Crosslinking by genipin was necessary, but not sufficient, for successful vascularization of narrow channels. Reverse pressure promoted migration of endothelium to narrow regions in tapered collagen channels. Enhanced cAMP levels and/or forward pressure promoted endothelial stability (i.e., the smallest confluent diameter remained the same or decreased over time). Twenty-μm-diameter, 1-mm-long channels could be vascularized in three days by the combination of a stiff gel, intermediate reverse pressure, and high cAMP.

FIGURE 6.

Summary of capillary-scale vascularization in type I collagen channels. (A) Modes of vascularization under different culture conditions. (B) Mechanisms that underlie capillary-scale vascularization.

Role of Chemical and Physical Signals in Vascularization

The roles of crosslinking and cAMP in the vascularization of capillary-scale channels are consistent with past studies in much larger channels.6, 38 We used genipin to stiffen type I collagen scaffolds from an elastic modulus of ~260 Pa to ~1330 Pa. This degree of stiffening has been shown previously to improve vascular stability of large endothelial tubes.6 In capillary-scale channels, crosslinking of collagen was required for the stability of endothelium as the cells migrated along a bare channel. Similarly, we have previously shown that elevated cAMP levels allowed large endothelial tubes to maintain patency over weeks, in part through improved barrier function.38 In capillary-scale channels, elevated cAMP levels promoted stability of endothelium, successfully counteracting the destabilization of endothelium by reverse pressure.

Previous findings suggest that a mechanical balance at the cell-scaffold interface controls vascular stability in collagen and fibrin gels.36-38 This principle implies that forward pressure would stabilize vessels in capillary-scale channels by reducing the tensile stress at the cell-scaffold interface. Indeed, we found that forward pressure was stabilizing (Fig. 4A), while high reverse pressure was destabilizing (Fig. 5C). This concept also predicts that forward pressure could promote vascularization by “pushing” endothelial cells to smaller channel diameters. Surprisingly, our current findings did not find that forward pressure increased endothelial coverage; on the contrary, reverse pressure promoted migration of cells to distal regions.

How does reverse pressure promote endothelial migration? Several possibilities are plausible. First, the “plugs” of debris that only emerged under forward pressure may physically impede migration. Second, the direction of flow affects endothelial cell migration in vitro.8, 10, 22, 33 Endothelial cells in a confluent monolayer tend to migrate upstream as a sheet, and downstream as dispersed cells.8, 12 In capillary-scale channels, forward pressure often resulted in the migration of single cells downstream, while reverse pressure (in the presence of high cAMP) favored migration of cells as a tube (Fig. 3). Third, the magnitude of shear stress affects cell migration in vitro.22, 31 We found that pressure direction modulated flow rates, and hence the shear stress, in seeded channels: under reverse pressure of 1.5 cm H2O, flow remained steady at ~2 μL/hr (corresponding to a shear of ~5-15 dyn/cm2 over the course of three days, assuming flow obeyed Poiseuille’s Law), while under forward pressure of the same magnitude, flow decreased to ~0.25 μL/hr by day 4 (shear of ~1-3 dyn/cm2).

To elucidate the role of shear stress in capillary-scale vascularization, we correlated shear with endothelial migration rate along ~20-μm-diameter channels. Migration rate over the first two days exhibited a one-phase decay relationship with shear stress magnitude (r2 = 0.59, p = 0.0001) (Fig. 5D). Migration rate reached a maximum of ~14 μm/hr when shears exceeded ~10 dyn/cm2. This result is consistent with a recent study that found a shear threshold of ~10 dyn/cm2 for angiogenic sprouting.9 Altogether, our results suggest that intermediate reverse pressure promotes stable vascularization because the shear stress exceeds a threshold value and the pressure is not high enough to destabilize the vessel wall.

We note that concomitant changes in transmural pressure are unlikely to affect migration speed because the endothelium migrates under reverse pressure as an open tube. Just distal to the furthest endothelium (i.e, just beyond the leading edge of migration), the gel is in direct fluidic contact with bare channel. Thus, the transmural pressure at the furthest endothelium will be effectively zero, regardless of the magnitude of applied pressure.27

Implications for Vascularizing Biomaterials

Our work provides a simple and rapid approach to generate capillary-scale vessels within a biomaterial or engineered tissue. This approach consists of: 1) patterning the material with a capillary-scale channel, 2) stiffening the matrix to an elastic modulus of >1 kPa, and 3) seeding and culturing the scaffold under intermediate reverse pressure and high cAMP. This strategy may be useful when vascularizing capillary-scale channels in reconstituted gels of extracellular matrix and in decellularized whole-organ scaffolds. For instance, successful revascularization on the capillary scale is the main determinant of whether decellularized organs can be perfused with blood without thrombosis or hemorrhage.2 Typical revascularization protocols have relied on forward pressure provided by bioreactors or are driven by gravity.23, 24, 28 These conditions do not yet support complete endothelial coverage of basement membrane channels; recently, endothelial coverage of ~75% was achieved in decellularized lung scaffolds.28 Our results provide one potential remedy, and suggest that stiffening the decellularized scaffold, culturing under reverse pressure, and elevating cAMP levels after seeding may help promote capillary formation.

Many other approaches have been developed to vascularize biomaterials for tissue engineering applications.16 To date, the most popular approaches to vascularization rely on angiogenesis and/or vasculogenesis. These processes do not allow immediate perfusion of an engineered tissue, as endothelial cells must first locally degrade the surrounding extracellular matrix to sprout and/or self-organize into vascular networks. For example, over the course of four days, endothelial sprouts extended at ~6 μm/hr in solid fibrin gels.11 Similarly, cocultured endothelial cells and fibroblasts required 2-3 weeks to form perfusable interconnected networks within ~1 mm3 fibrin gels.20 During this time, cells can only be fed through diffusion and/or interstitial flow. Our work shows that application of elevated cAMP levels and intermediate reverse pressure resulted in rapid vascularization of stiffened ~20-μm-diameter channels. Endothelium migrated along channels at a rate of 10-15 μm/hr, generating perfusable 1-mm-long vessels in three days or less. We note that even before a complete capillary forms along a channel, perfusion can be initiated and maintained.

CONCLUSIONS

This work reports physical and chemical signals that promote capillary-scale vascularization of collagen gels. We found that reverse pressure promoted endothelial migration but destabilized the resulting endothelium. Gel stiffening and elevated cAMP levels promoted endothelial stability. Together, these conditions improved vascularization of capillary-scale channels, as cAMP counteracted the destabilization by reverse pressure. By applying these signals when vascularizing 20-μm-diameter channels, we could rapidly generate capillary-scale vessels with precise control over vascular geometry. This result may aid in the formation of capillaries in engineered tissues and in the generation of perfusable capillaries for study of normal and pathological vascularization, such as that observed along tumor basement membrane sleeves following discontinuation of anti-VEGF therapy.17 Our data also imply that a physical limit may exist for vascularization along small channels; a similar result was recently reported for epithelial cell migration along cylindrical wires.39 Additional signals that would allow vascularization along channels narrower than ~20 μm remain to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Cliff Brangwynne and Marina Feric for access to their pipette puller, and Aimal Khankhel for assistance with experiments. This work was supported by Boston University through a Dean’s Catalyst Award (J.T.), a Lutchen Fellowship (R.M.L.), and awards from the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (R.M.L., N.F.B., G.C.). R.M.L. thanks Mr. and Mrs. William Felder for support through a Summer Term Alumni Research Scholarship at Boston University.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Raleigh M. Linville, Nelson F. Boland, Gil Covarrubias, Gavrielle M. Price, and Joe Tien declare that they have no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

No human or animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auger FA, Gibot L, Lacroix D. The pivotal role of vascularization in tissue engineering. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2013;15:177–200. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071812-152428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badylak SF, Taylor D, Uygun K. Whole-organ tissue engineering: decellularization and recellularization of three-dimensional matrix scaffolds. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2011;13:27–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071910-124743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogorad MI, DeStefano J, Karlsson J, Wong AD, Gerecht S, Searson PC. In vitro microvessel models. Lab on a chip. 2015;15:4242–55. doi: 10.1039/c5lc00832h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Califano JP, Reinhart-King CA. Exogenous and endogenous force regulation of endothelial cell behavior. J. Biomech. 2010;43:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan JM, Zervantonakis IK, Rimchala T, Polacheck WJ, Whisler J, Kamm RD. Engineering of in vitro 3D capillary beds by self-directed angiogenic sprouting. PloS one. 2012;7:e50582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan KLS, Khankhel AH, Thompson RL, Coisman BJ, Wong KHK, Truslow JG, Tien J. Crosslinking of collagen scaffolds promotes blood and lymphatic vascular stability. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2014;102:3186–95. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chrobak KM, Potter DR, Tien J. Formation of perfused, functional microvascular tubes in vitro. Microvasc. Res. 2006;71:185–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewey CF, Bussolari SR, Gimbrone MA, Davies PF. The dynamic response of vascular endothelial cells to fluid shear stress. J. Biomech. Eng. 1981;103:177–85. doi: 10.1115/1.3138276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galie PA, Nguyen DH, Choi CK, Cohen DM, Janmey PA, Chen CS. Fluid shear stress threshold regulates angiogenic sprouting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014;111:7968–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310842111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu PP, Li S, Li YS, Usami S, Ratcliffe A, Wang X, Chien S. Effects of flow patterns on endothelial cell migration into a zone of mechanical denudation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;285:751–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S, Lee H, Chung M, Jeon NL. Engineering of functional, perfusable 3D microvascular networks on a chip. Lab on a chip. 2013;13:1489–500. doi: 10.1039/c3lc41320a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiosses WB, McKee NH, Kalnins VL. Evidence for the migration of aortic endothelial cells towards the heart. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997;2891:2891–96. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koike N, Fukumura D, Gralla O, Au P, Schechner JS, Jain RK. Creation of long-lasting blood vessels. Nature. 2004;428:138–39. doi: 10.1038/428138a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung AD, Wong KHK, Tien J. Plasma expanders stabilize human microvessels in microfluidic scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2012;100:1815–22. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levenberg S, Rouwkema J, Macdonald M, Garfein ES, Kohane DS, Darland DC, Marini R, van Blitterswijk CA, Mulligan RC, D'Amore PA, Langer R. Engineering vascularized skeletal muscle tissue. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:879–84. doi: 10.1038/nbt1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovett M, Lee K, Edwards A, Kaplan DL. Vascularization strategies for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. B. 2009;15:353–70. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mancuso MR, Davis R, Norberg SM, O'Brien S, Sennino B, Nakahara T, Yao VJ, Inai T, Brooks P, Freimark B, Shalinsky DR, Hu-Lowe DD, McDonald DM. Rapid vascular regrowth in tumors after reversal of VEGF inhibition. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2610–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI24612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan JP, Delnero PF, Zheng Y, Verbridge SS, Chen J, Craven M, Choi NW, Diaz-Santana A, Kermani P, Hempstead B, Lopez JA, Corso TN, Fischbach C, Stroock AD. Formation of microvascular networks in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:1820–36. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morin KT, Smith AO, Davis GE, Tranquillo RT. Aligned human microvessels formed in 3D fibrin gel by constraint of gel contraction. Microvasc. Res. 2013;90:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moya ML, Hsu YH, Lee AP, Hughes CC, George SC. In vitro perfused human capillary networks. Tissue Eng. C. 2013;19:730–7. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nichol JW, Koshy ST, Bae H, Hwang CM, Yamanlar S, Khademhosseini A. Cell-laden microengineered gelatin methacrylate hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5536–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostrowski MA, Huang NF, Walker TW, Verwijlen T, Poplawski C, Khoo AS, Cooke JP, Fuller GG, Dunn AR. Microvascular endothelial cells migrate upstream and align against the shear stress field created by impinging flow. Biophys. J. 2014;106:366–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.11.4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ott HC, Clippinger B, Conrad C, Schuetz C, Pomerantseva I, Ikonomou L, Kotton D, Vacanti JP. Regeneration and orthotopic transplantation of a bioartificial lung. Nat. Med. 2010;16:927–33. doi: 10.1038/nm.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen TH, Calle EA, Zhao L, Lee EJ, Gui L, Raredon MB, Gavrilov K, Yi T, Zhuang ZW, Breuer C, Herzog E, Niklason LE. Tissue-engineered lungs for in vivo implantation. Science. 2010;329:538–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1189345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettersson A, Nagy JA, Brown LF, Sundberg C, Morgan E, Jungles S, Carter R, Krieger JE, Manseau EJ, Harvey VS, Eckelhoefer IA, Feng D, Dvorak AM, Mulligan RC, Dvorak HF. Heterogeneity of the angiogenic response induced in different normal adult tissues by vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor. Lab. Invest. 2000;80:99–115. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price GM, Chrobak KM, Tien J. Effect of cyclic AMP on barrier function of human lymphatic microvascular tubes. Microvasc. Res. 2008;76:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price GM, Wong KHK, Truslow JG, Leung AD, Acharya C, Tien J. Effect of mechanical factors on the function of engineered human blood microvessels in microfluidic collagen gels. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6182–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren X, Moser PT, Gilpin SE, Okamoto T, Wu T, Tapias LF, Mercier FE, Xiong L, Ghawi R, Scadden DT, Mathisen DJ, Ott HC. Engineering pulmonary vasculature in decellularized rat and human lungs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:1097–102. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scarritt ME, Pashos NC, Bunnell BA. A review of cellularization strategies for tissue engineering of whole organs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2015;3:43. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2015.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang MD, Golden AP, Tien J. Molding of three-dimensional microstructures of gels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12988–9. doi: 10.1021/ja037677h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teichmann J, Morgenstern A, Seebach J, Schnittler HJ, Werner C, Pompe T. The control of endothelial cell adhesion and migration by shear stress and matrix-substrate anchorage. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1959–69. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Truslow JG, Price GM, Tien J. Computational design of drainage systems for vascularized scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4435–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vickerman V, Kamm RD. Mechanism of a flow-gated angiogenesis switch: early signaling events at cell-matrix and cell-cell junctions. Integr. Biol. 2012;4:863–74. doi: 10.1039/c2ib00184e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whisler JA, Chen MB, Kamm RD. Control of perfusable microvascular network morphology using a multiculture microfluidic system. Tissue Eng. C. 2014;20:543–52. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2013.0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong KHK, Chan JM, Kamm RD, Tien J. Microfluidic models of vascular functions. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012;14:205–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071811-150052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong KHK, Truslow JG, Khankhel AH, Chan KLS, Tien J. Artificial lymphatic drainage systems for vascularized microfluidic scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2013;101:2181–90. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong KHK, Truslow JG, Khankhel AH, Tien J. Biophysical mechanisms that govern the vascularization of microfluidic scaffolds. In: Brey EM, editor. Vascularization. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2014. pp. 109–24. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong KHK, Truslow JG, Tien J. The role of cyclic AMP in normalizing the function of engineered human blood microvessels in microfluidic collagen gels. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4706–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yevick HG, Duclos G, Bonnet I, Silberzan P. Architecture and migration of an epithelium on a cylindrical wire. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015;112:5944–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418857112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng Y, Chen J, Craven M, Choi NW, Totorica S, Diaz-Santana A, Kermani P, Hempstead B, Fischbach-Teschl C, Lopez JA, Stroock AD. In vitro microvessels for the study of angiogenesis and thrombosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:9342–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201240109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]