Abstract

Aberrant activation of the developing immune system can have long-term negative consequences on cognition and behavior. Teratogens, such as alcohol, activate microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, which could contribute to the lifelong deficits in learning and memory observed in humans with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) and in rodent models of FASD. The current study investigates the microglial response of the brain 24 hours following neonatal alcohol exposure (postnatal days 4–9, 5.25 g/kg/day). On postnatal day 10, microglial cell counts and area of cell territory were assessed using unbiased stereology in the hippocampal subfields CA1, CA3 and dentate gyrus, and hippocampal expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory genes was analyzed. A significant decrease in microglial cell counts in CA1 and dentate gyrus was found in alcohol-exposed and sham-intubated animals compared to undisturbed suckle controls, suggesting overlapping effects of alcohol exposure and intubation alone on the neuroimmune response. Cell territory was decreased in alcohol-exposed animals in CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus compared to controls, suggesting the microglia have shifted to a more activated state following alcohol treatment. Furthermore, both alcohol-exposed and sham-intubated animals had increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, CD11b, and CCL4; in addition, CCL4 was significantly increased in alcohol-exposed animals compared to sham-intubated as well. Alcohol-exposed animals also showed increased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β compared to both sham-intubated and suckle controls. In summary, the number and activation of microglia in the neonatal hippocampus are both affected in a rat model of FASD, along with increased gene expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. This study shows that alcohol exposure during development induces a neuroimmune response, potentially contributing to long-term alcohol-related changes to cognition, behavior and immune function.

Keywords: FASD, neuroimmune, development, cytokines, pro-inflammatory

1. Introduction

Prenatal alcohol exposure can lead to the development of serious cognitive and behavioral deficits which arise from structural and functional changes in the brain. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) are estimated to affect up to 5% of live births each year (Sampson et al., 1997; May, 2009; CDC, 2015), making prevention and treatment of these disorders of the utmost importance. Brain regions such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex are vulnerable to the teratogenic effects of alcohol during the “brain growth spurt” which occurs during the third trimester of pregnancy in humans and the first two postnatal weeks in rats (Dobbing & Sands, 1979; Mooney et al., 1996; Goodlett and Eilers, 1997; Klintsova et al., 2007), making alcohol exposure during this time window particularly devastating for these brain areas.

Recent work has suggested alcohol-induced neuroinflammation, as measured by increased activation of microglia and levels of associated cytokines, as a potential secondary source of damage in various models of alcohol exposure, both during development and in adulthood (McClain et al., 2011; Saito et al., 2010; Kane et al., 2011; Tiwari & Chopra, 2011; Marshall et al., 2013; Drew et al., 2015; Topper et al., 2015). Alcohol exposure during the third trimester-equivalent induces waves of apoptosis in the hippocampus, possibly triggering microglial migration to the damaged tissue and activation of the resident microglia to phagocytose dying cells and debris (Miller, 1998; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2015). Microglial activation in response to alcohol has been suggested to not only be a consequence of the insult also but a source of inflammation and tissue damage (Marshall et al., 2013).

The rodent immune system begins development during gestation and continues through the first two weeks of neonatal life, with microglia beginning colonization on embryonic days 9–10 in a brain-region specific manner (Chan et al., 2007; Ginhoux et al., 2010). Microglia respond to immune challenges through release of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and phagocytosis of dying neurons and pathogens. Aberrant microglia activation during development can lead to chronically increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines which could lead to neurodevelopmental and psychopathological disorders (Cai et al., 2000; Meyer et al., 2006; Urakubo et al., 2001) or exaggerated immune responses to challenges later in life (Bilbo & Schwarz, 2009; 2012).

Microglia can express both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in response to an immune challenge. The release of cytokine and phagocytosis of debris is linked with microglial morphology (Gehrmann et al., 1995; Neumann et al., 2009). Microglia exhibit various activation states characterized by changes to their physical shape and size. Resting or quiescent microglia are characterized by a small soma and long, thin processes for surveying the local microenvironment for pathogens or injury (Figure 1A). Once a pathogen has been detected the microglia’s soma enlarges and its processes shorten and thicken. A fully activated microglia displays a round, amoeboid shape with either very short or complete lack of processes (Figure 1B; Nimmerjahn et al., 2005; Olah et al., 2011; Fu et al., 2014). Pro-inflammatory cytokines, released by activated microglia and macrophages, have cytotoxic effects and can induce further cell loss and tissue damage, while anti-inflammatory cytokines inhibit expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, initiate cellular repair, and are generally thought to be neuroprotective. A balance between the actions of these cytokines dictates how the brain recovers from immune challenges.

Figure 1.

Representative images of Iba-1+ microglia in the postnatal day 10 rat hippocampus. A) Quiescent microglia with small somas and long, thin processes. B) Fully activated amoeboid microglia with a large, round soma and very short processes. Both images taken with a 40x lens. C) Iba-1 immunostaining in the neonatal rat hippocampal CA1. Image taken with a 20x lens.

The current study investigates whether third trimester-equivalent (postnatal days [PD]) 4–9) binge-like alcohol exposure affects microglial activation in the neonatal rat hippocampus through analysis of subregion-specific microglial number and territory (area) occupied by microglial body and processes. Cell territory provides an indirect measure of activation state, as a smaller area would indicate a more activated morphology (Drew & Kane, 2014). Neuroinflammation was also measured through analysis of gene expression of four pro-inflammatory cytokines: IL-1β, TNF-α, CD11b, and CCL4, and one anti-inflammatory cytokine: TGF-β. We hypothesized that our model of alcohol exposure would increase the number of microglial cells in hippocampus of neonatal rats, activate existing microglia, and increase production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This study will give a starting point for assessing whether aberrant neuroimmune activation via neonatal alcohol exposure could have long-term consequences for the brain and behavior.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1 Animals

Timed-pregnant Long-Evans rat dams were acquired from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and housed in cages of standard dimensions (17 cm high x 145 cm long x 24 cm wide) in a 12/12 hr light cycle (lights on at 9:00 AM) upon arrival. On postnatal day (PD) 3, each litter was culled to eight pups (6 male, 2 female when possible) and markings for pup identification were made by injecting a small volume of non-toxic India black ink into the paws. On PD 4, a split-litter design was used to assign the pups to one of three experimental groups: suckle control (SC), sham-intubated (SI) or alcohol-exposed (AE). AE and SI pups were represented in the same litter and SC pups from a separate litter to allow these pups to be left completely undisturbed aside from daily weighing. Following the alcohol exposure, pups were left undisturbed with the dam until sacrifice on PD10. A total of 60 male pups from 21 litters were used for the data presented here. More specifically, for stereology, 10 AE, 9 SI and 8 SC pups were used; for gene expression, 9 AE, 12 SI and 12 SC pups were used. Animals used for stereology were also administered a 50 mg/kg bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) i.p. injection 2 hours prior to sacrifice to be used to answer additional questions not reported here. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the animal use protocol approved by University of Delaware Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with NIH’s Animal Care Guidelines.

2.2 Alcohol exposure paradigm

On PD 4–9, AE pups received 5.25 g/kg/day alcohol in a milk formula (11.9% v/v) in 2 doses, 2 hours apart via intragastric intubation. On PD4, AE pups also received two milk-only feedings as a caloric supplement 2 and 4 hours following the second alcohol dose; on PD 5–9, AE pups were given one milk-only feeding two hours following the second alcohol dose. SI pups were intubated alongside the AE rats as an intubation control but received no liquid solution. Previous work has suggested that delivery of milk formula to the SI pups could result in accelerated weight gain. SC pups remained undisturbed with the dam except for daily weighing to insure proper development.

2.3 Blood alcohol concentrations (BACs)

On PD 4, 90 minutes following the second alcohol exposure, blood samples were collected through tail clippings from both the AE and SI groups. Blood samples from the AE group were centrifuged (15,000 rpm/25 minutes) and the plasma collected and stored at −20°C until analysis. BACs were analyzed using an Analox GL5 Alcohol Analyzer (Analox Instruments, Boston, MA).

2.4 Immunohistochemistry

On PD10, animals were deeply anesthetized (ketamine/xylazine cocktail), transcardially perfused (0.1M PBS with heparin followed by 4% paraformaldehyde) and the brains were stored in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours. The brains were then transferred into 30% sucrose in 4% paraformaldehyde until sectioning. Brains were sectioned horizontally at 40 µm through the entirety of the hippocampus and collected in wells maintaining the order. Microglia were identified with microglia-specific marker ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba-1). Briefly, sections were washed in 0.1M Tris-buffered saline (TBS), incubated in 2% H2O2 in 70% methanol for 10 min, blocked in 3% normal goat serum and 1% Triton-X in 0.1M TBS for 1 hr, then transferred into anti-Iba-1 primary antibody (Wako Chemicals; 1:5000) for 48 hours. Sections were incubated in secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG made in goat; 1:200; Sigma) for 1 hr and the immunolabeling was visualized using nickel-enhanced diaminobenzidine (DAB). Two control sections per animal were processed identically to the immunolabeled sections but were placed in blocking solution only instead of primary antibody during the steps listed above; staining of these sections insured antigen-specific labeling.

2.5 Cell quantification

Sections used for cell quantification were selected in a systematic random manner (1/12th sampling fraction). Iba-1+ cells were counted using unbiased stereology within a known volume of CA1, CA3, and the dentate gyrus (DG) subregions of the hippocampus (CA1 shown in Figure 1C), using the optical fractionator probe (Stereo Investigator, MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT). All regions of each hippocampal subfield were included in the analyses (e.g. for DG, the molecular layer, granule cell layer and the hilus were counted). The sampling grid was set to 200 × 200 µm and the counting frame set to 100 × 100 µm. A dissector height of 12 µm and a guard zone of 2 µm on either side of the section was used. For all counts, the mean coefficient of error (CE) did not exceed the recommended 0.1 (Gunderson, 1986).

2.6 Microglial Cell Territory

As an indirect estimate of microglia morphology and activation state, total cell area or “territory” (Drew et al., 2015) was measured for the cell layers of CA1, CA3, and DG using NeuroLucida software (MBF BioScience, Williston, VT). For each section, the area encompassed by an individual microglia was measured by tracing a contour from the tip of each microglial process to the next. Five pseudorandomly selected microglia were traced per section from microglia located within the cell layer or immediately adjacent with at least one process extending into the cell layer. For each animal, 5–8 sections were used per subregion, as the regions were not always present in the most dorsal or ventral sections. The areas of the microglia were then averaged within and across sections. Activated microglia are usually characterized by shorter, thicker processes and a larger soma (Figure 1A) whereas resting microglia have longer, thinner processes (Figure 1B), meaning that smaller microglia cell territory would indicate a more activated morphology.

2.7 Gene expression assays

On PD10, animals were rapidly decapitated and the brains frozen with −20°C 2-methylbutane and stored at −80°C until processing. Dorsal and ventral hippocampus were dissected on dry ice and DNA/RNA were extracted (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Quantification and analysis of nucleic acid quality were performed with spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000, ThermoScientific) and reverse transcription was performed using the Quantitect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was amplified with real-time PCR (Bio-Rad, CFX96). Gene expression for TNF, ITGAM (CD11b), CCL4, IL10, and TGFB1 was assessed using Taqman probes (Life Technologies), and tubulin as a reference gene (Table 1). IL1B gene expression was assessed using SYBR (Bio-Rad) and the appropriate forward and reverse primers, with GAPDH used as a reference gene. The sequences of primers for IL1B and GAPDH were: IL1B forward: GAAGTCAAGACCAAAGTGG, reverse: TGAAGTCAACTATGTCCCG; GAPDH forward: GTTTGTGATGGGTGTGAACC, reverse: TCTTCTGAGTGGCAGTGATG (Posillico & Schwarz, 2015). Levels of tubulin and GAPDH were not altered by neonatal treatment, as determined by one-way analysis of variance (F < 1) (Boschen et al., 2015). All reactions for each gene target and reference were run in triplicate, except for IL1B and GAPDH which were run in duplicate. Product specificity was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis or melt curve (IL1B and GAPDH). Levels of IL10 were not detectable in the PD10 brain and thus will not be discussed in the Results section (see Discussion for further information).

Table 1.

List of gene expression primers.

| Gene | Encoded Protein | Catalog No. |

|---|---|---|

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) | Rn01525859 |

| ITGAM | Cluster of differentiation molecule 11B (CD11b) | Rn00709342 |

| CCL4 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 (CCL4) | Rn00671924 |

| IL1B | Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) | Custom primers |

| IL10 | Interleukin-10 (IL-10) | Rn01483988 |

| TGFB1 | Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) | Rn00572010 |

| Tubulin | Tubulin | Rn01435337 |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) |

Custom primers |

2.8 Statistical Analysis

Animal weights for PD4, 9, and 10 were averaged within neonatal condition and analyzed using a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA; day x neonatal condition) followed by post hoc tests when appropriate. For BACs, average BAC for each animal (2–3 analyses per animal) ± standard error of the mean (SEM) are reported as mg/dl. Microglia number and cell territory were assessed using one-way ANOVA. Post hoc tests (Tukey’s) were used when appropriate. The comparative Ct method was used to obtain the relative fold change in gene expression of experimental (AE or SI) vs. the average of controls (SC) per plate (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Comparisons between the AE and SI groups were performed using unpaired t-tests and comparisons between the experimental (AE and SI) and the control group (SC) were analyzed with a one-sample t-test (hypothetical value set to 1.0) as commonly done in the field (e.g. Roth et al., 2009; Blaze & Roth, 2013; Debruin et al., 2014). Using this method, a mean value of 1 indicates no change in mRNA transcript level compared to the SC group. Raw p-values are listed for the gene expression data; all significant values retain significance using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (q = 0.05) to control for the false discovery rate in multiple comparisons (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Differences were considered to be statistically significant at p < 0.05 and nonsignificant trends at p < 0.1 are also reported. Outliers for each neonatal treatment group were identified using Grubb's test. No outliers were removed for cell count or cell territory; for gene expression data, the number of outliers removed for each gene assay was as follows: CCL4: 3, ITGAM (CDllb): 2, TGFB1: 2, IL1B: 1, TNF: 0. Weights analyses were run using SPSS 16 and all other statistical analyses were run using Prism 6 software (GraphPad Inc.).

3. Results

3.1 Animal weights

Animals were weighted daily during the alcohol exposure paradigm. PD4, 9 and 10 weights were compared to assess potential changes in nutritional status due to neonatal condition. A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of day (F(2,114) = 2278.657, p < 0.001), as all animals increased in body weight across the treatment period. A significant day x neonatal condition interaction was found (F(4,114) = 14.887, p < 0.001). One-way ANOVAs were then run separately for PD4, 9 and 10. For PD4, pups weighed similarly regardless of neonatal condition (F(2,57) = .413, p = 0.664), however on PD9 and 10, a significant main effect of neonatal condition was found (F(2,57) = 7.764, p = 0.001; F(2,57) = 7.243, p = 0.002). Post hoc Tukey’s tests revealed that on PD9 and 10, AE animals weighed significantly less than SI and SC pups (PD9: AE vs. SI: p = 0.001, AE vs. SC: p = 0.024, SI vs. SC: p = 0.499; PD10: AE vs. SI: p = 0.001, AE vs. SC: p = 0.031, SI vs. SC: p = 0.519). Previous work from our lab has shown that this difference in weight gain is limited to the neonatal treatment period, as AE animals are indistinguishable from control animals by PD30 (Hamilton et al., 2012; Boschen et al., 2014).

3.2 Blood alcohol concentrations (BACs)

BACs were collected from a tail clip on PD4, 90 min following the second alcohol dose. One AE animal was excluded due to too little plasma being collected to accurately perform the Analox analysis. The average BAC was 358.97 mg/dl (± 88.14 SEM), which is consistent with other published BAC levels from our lab using the same alcohol exposure model (Boschen et al., 2014; 2015).

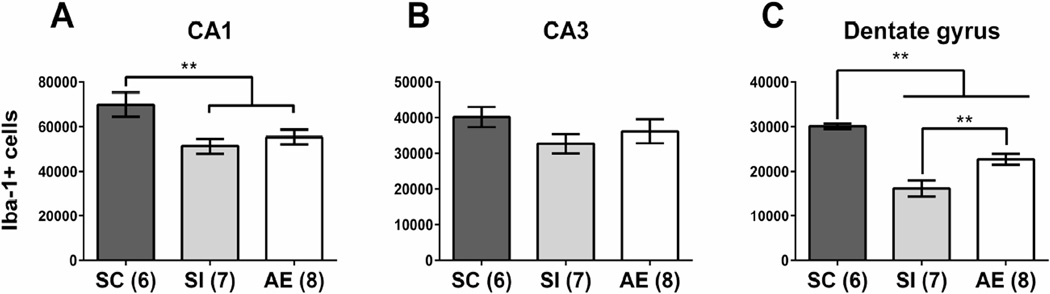

3.3 Microglial number by hippocampal subregion

Total microglial cell counts were estimated using unbiased stereological analysis of Iba-1+ cells in hippocampal CA1, CA3, and DG subregions. Subregion-specific effects were observed, with significant decreases in microglial number found in AE and SI compared to SC in CA1 and DG, but not in CA3 (Figure 2A–C). Specifically, in CA1, a significant main effect of neonatal treatment was also found (F(2,18) = 5.433, p = 0.0143), with significantly decreased cell numbers found for the AE and SI groups compared to SC (p < 0.05, Tukey’s post hoc; Figure 2A). In the DG, there was a main effect of neonatal condition (F(2,18) = 25.56, p = 0.0001), with Tukey’s post hoc analysis finding a significant different between both AE and SI groups and the SC group (p < 0.05; Figure 2C). Notably, while animals from both AE and SI postnatal conditions had a lower number of microglia than SC, a significant higher number of Iba-1+ cells was found in the AE animals compared to the SI (p = 0.005). There were no significant effects in CA3 (p > 0.05, Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Microglial cell counts. Number of Iba-1+ microglia were significantly decreased in hippocampal CA1 (A) of AE and SI animals compared to the SC group. No effect of neonatal treatment was found in CA3 (B). In dentate gyrus (C), AE and SI animals had fewer microglia compared to the SC group, but the AE group also had significantly more microglia compared to the SI animals. AE = alcohol-exposed, SI = sham-intubated, SC = suckle control. ** = p < 0.01.

3.4 Microglial cell territory

Area of cell territory was measured in microglia residing within the cell layer of the CA1, CA3, and DG subregions. Significant decreases in microglial cell territory (measured in µm2) were found in alcohol-exposed animals in CA1 and DG (Figure 3A–C). For CA1, a main effect of neonatal condition was found (F(2,15) = 15.14, p = 0.0003), with Tukey’s post hoc analysis indicating a significant decreased in cell territory in the AE group compared to both the SI and SC groups (p < 0.05 and 0.001, respectively; Figure 3A). SC and SI did not differ in cell territory from one another. In CA3, a main effect of neonatal condition was found (F(2,15) = 7.779, p = 0.0048), showing a significant decrease in cell territory for AE animals compared to both the SI and SC groups (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively; Figure 3B). Again, SI and SC groups did not differ. For DG, there was a main effect of neonatal condition (F(2,15) = 4.487, p = 0.029), with a significant decrease in cell territory in AE animals compared to SC, but not SI, animals (p < 0.05, Figure 3C). SI did not differ significantly from the SC or AE groups.

Figure 3.

Microglia cell territory. A) In CA1, the average area covered by each microglia was decreased in the AE group compared to the SI and SC groups (p < 0.05 and 0.001, respectively). B) In CA3, cell territory was decreased in the AE group compared to SI and SC (p < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively). C) The AE group had significantly smaller microglia in the dentate gyrus (DG) compared to the SC group (p < 0.05), but was not significantly different from SI. Visualization of the size of the microglia measured in each region when categorized as small, medium or large. D) Representative drawings of small, medium, and large microglia. E) CA1, F) CA3, G) DG. AE = alcohol-exposed, SI = sham-intubated, SC = suckle control. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

Microglia were then classified into size categories to better visualize the differences in cell territory between AE and control animals (Figure 3D–G). The microglia were classified as “small” (<1000 µm2), “medium” (1000–2000 µm2), or “large” (>2000 µm2) (representative illustrations shown in Figure 3D) and the percentage of each category was calculated from the total number of cells analyzed for each animal. Most microglia in all regions and neonatal conditions fell into the “medium” classification, but some shifts in microglial size were observable between conditions. For all three regions, one-way ANOVAs were run to analyze shifts in the number of microglia classified as “small” or “large” in each area, as these categories would capture the most activated (“small”) or least activated (“large”) phenotypes. In CA1, a significant main effect of neonatal condition was found for number of “small microglia” (F(2,15) = 5.266, p = 0.019, with post hoc tests (Tukey’s) revealing a significant differences between AE and SI (p < 0.05) and AE and SC (p < 0.05), but not SI and SC. For “large” microglia in CA1, a main effect of neonatal treatment was found (F(2,15) = 8.661, p = 0.003), with significant differences between AE and SC (p < 0.01) and SC and SI (p < 0.05), but not AE and SI. In CA3, a significant effect of neonatal treatment was revealed for “small” microglia (F(2,15) = 3.824, p = 0.0455), with differences between AE and SI (p < 0.05), but not between SC and SI or SC and AE. For “large” microglia in CA3, a significant main effect of treatment was found (F(2,15) = 6.602, p = 0.009), with differences between AE and SI (p < 0.05) and AE and SC (p < 0.05), but not between SI and SC. In DG, there was no main effect of neonatal condition on the percentage of “small” or “large” microglia (p > 0.05), suggesting that the shifts in microglial size in the DG, while sufficient to be statistically significant between SC and AE when assessing average cell territory, were more subtle then the shifts found in the other two brain regions.

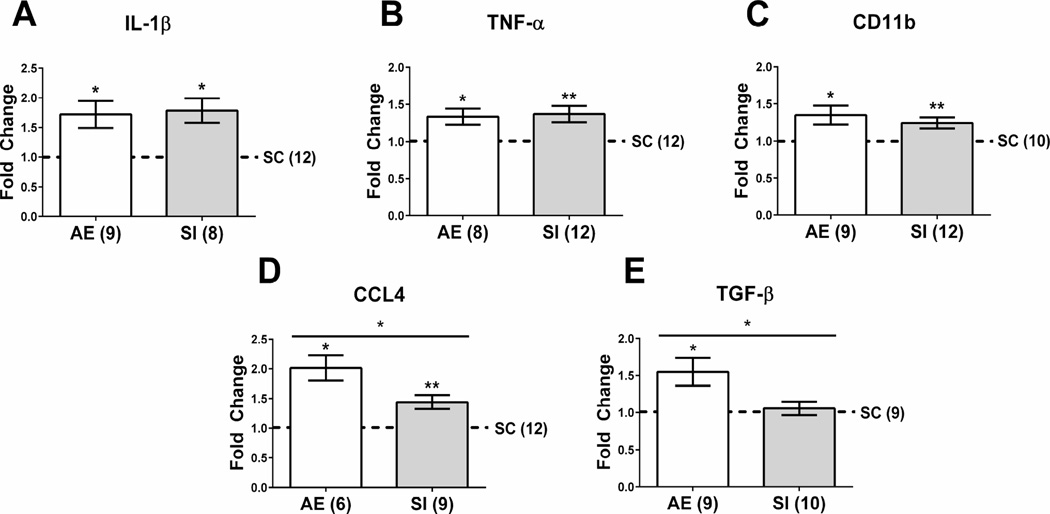

3.5 Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine gene expression

Cytokine gene expression was assessed using whole hippocampal tissue. We found that levels of three of the pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and CD11b) were increased in both AE and SI groups compared to the SC group and unpaired t-tests revealed no significant difference between AE and SI (t < 1, p > 0.05) (Figure 4A–C). For IL-1β, both AE and SI groups had increased levels compared to SC (for AE vs. SC: t(8) = 3.160, p = 0.013; for SI vs. SC: t(7) = 3.778, p = 0.007). For TNF-α, both AE and SI were increased compared to SC (for AE vs. SC: t(7) = 3.096, p = 0.017; for SI vs. SC: t(9) = 3.34, p = 0.009). For CD11b, levels were increased in both AE and SI groups compared to SC (for AE vs. SC: t(8) = 2.73, p = 0.026; for SI vs. SC: t(11) = 3.275, p = 0.007). Interestingly, while pro-inflammatory cytokine CCL4 was significantly increased in both AE and SI compared to the SC group (for AE vs. SC: t(5) = 4.821, p = 0.0048; for SI vs. SC: t(8) = 3.716, p = 0.0059), an unpaired t-test revealed that levels of CCL4 were significantly increased in AE compared to SI animals as well (t(13) = 2.559, p = 0.0238; Figure 4D). Levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β were increased in AE animals vs. SC and SI controls (AE vs. SC: t(8) = 2.927, p = 0.019; AE vs. SI: t(17) = 2.439, p < 0.05; Figure 4E). These results indicate that while the SI group also show increases in some pro-inflammatory cytokine activity was increased in both AE and SI groups in comparison with SC, neonatal AE causes even greater expression of CCL4 and induces an anti-inflammatory response on PD10.

Figure 4.

Pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression in the neonatal hippocampus. Both AE and SI groups had elevated levels of IL-1β (A), TNF-α (B), and CD11b (C) compared to SC. For CCL4 (D), both AE and SI groups showed increased gene expression, however levels of CCL4 in the AE group were significantly higher than in the SI group (p < 0.05). E) Gene expression of anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β were significantly increased in the AE group over the SI and SC animals (p < 0.05). Data is expressed as a fold change from the suckle control (SC) group (shown as 1 on graphs). AE = alcohol-exposed, SI = sham-intubated, SC = suckle control. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

The current study investigated whether third trimester-equivalent binge-like alcohol exposure (PD 4–9) induces microglial response in the neonatal hippocampus. Overall, we found two main factors contributing to increases in neuroinflammation in the neonatal brain: alcohol exposure and stress of handling/intubation. We found both common and unique effects on microglial cell number and activation state. Specifically, PD4–9 alcohol exposure (AE) uniquely decreased microglia cell territory in the DG, CA3 and CA1, indicative of microglia with an activated morphology, and increased CCL4 and TGF-β gene expression compared to both control groups on PD10. We also found fewer microglia in the DG and CA1 subregions of AE and sham-intubated (SI) animals compared to suckle controls (SC), and that these groups showed similarly increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and CD11b. Decreased microglial number and enhanced expression of pro-inflammatory molecules in the AE and SI groups likely represent the brain’s generalized immune response to insult. Importantly, neuroinflammation was enhanced in AE animals as measured by increased microglial activation, increased expression of CCL4, and upregulation of the anti-inflammatory response as measured by TGF-β.

Region-specific decreases in Iba-1+ microglia numbers in the AE and SI groups compared to the SC group were seen in the DG and CA1 regions, but not CA3. These results differ from the previously demonstrated increased proliferation of microglia in response to high alcohol doses in adolescence and adulthood (Ward et al., 2009; McClain et al., 2011; Marshall et al., 2013). However, ethanol has been reported to be toxic to cultured microglia and caused loss of cerebellar microglia in vivo (24 hours following PD3–5 3.5 mg/kg ethanol in the neonatal mouse), with remaining microglia expressing activated morphological characteristics (Kane et al., 2011). Additionally, the stress hormone corticosterone can act on microglial glucocorticoid receptors to inhibit microglial proliferation in culture (Ganter et al., 1992), which could be playing a role in the current study, as our model of alcohol exposure has been previously shown to elevate levels of plasma corticosterone in AE and SI animals (Boschen et al., 2015). The current study cannot discern whether the observed decrease in microglia number was due to decreased proliferation, increased apoptosis of the microglia themselves, or changes to microglial migration. It is possible that the number of microglia across the entire brain remained constant across conditions and the decreases in the hippocampus were due to the microglia being recruited to other brain areas in the SI and AE groups, as amoeboid microglia have been reported to be highly motile (Brockhaus et al., 1996; Stence et al., 2001). Interestingly, a small but significant increase in microglial number was found in the AE group compared to SI in the DG, suggesting that alcohol exposure and stress intubation alone could affect microglial number at differing rates or on a different time course following the first insult. Our lab is currently exploring a more in-depth time course of the neuroimmune response following alcohol exposure to assess how these changes present across days.

Area of cell territory was used in this study as an indirect measure of microglial morphology and activation, as activated microglia have shorter processes with larger cell bodies compared to the long, thin processes found on resting microglia. The current study found that in CA1, CA3, and DG cell layers, the microglia in AE animals covered less territory with their processes, indicating that the microglia are activated following the alcohol exposure. While AE and SI animals both have decreased numbers of microglia in CA1 and DG, neonatal alcohol exposure causes the remaining microglia to exist in a more activated state. A similar method has been used previously to show that neonatal alcohol exposure reduces cell territory in the developing mouse hippocampal CA1, cerebellum and parietal cortex (Drew et al., 2015). The current study extends these results to a commonly used rat model of FASD, and shows increased microglial activation in all three subregions of the hippocampus. Further work is being done to elucidate differences in the time course of microglial activation and cytokine release in AE and SI pups. It is important to consider the potential effect of alcohol withdrawal on microglial activation in the current study, since the physiological signs and symptoms of withdrawal can begin in as little as 6 hours following alcohol administration in adult animals (Becker, 2000) and the pups in the current study were sacrificed 24 hours following the last alcohol exposure. Withdrawal symptoms are linked to neuronal excitotoxicity following a compensatory upregulation of NMDA signaling (Young et al., 2010, Idrus et al., 2014) and multiple withdrawal episodes are thought to act via elevated extracellular glutamate to prime microglia towards a more inflammatory response to subsequent alcohol exposures (Nixon et al., 2008; Ward et al., 2009; McClain et al., 2011), in part explaining why the microglia in the AE group had a more activated phenotype (smaller cell territory) compared to the SI and SC groups.

Alcohol can alter cytokine levels in a variety of tissues other than the brain, such as plasma, lungs, and liver (Crews et al., 2006). Both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines are found in both the peripheral and central nervous systems and can be produced by activated macrophages (including microglia), as well as certain other cell types, including astrocytes (Choi et al., 2014), other immune cells such as leukocytes and lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and, in the case of TNF-α, neurons. The current study found a significant increase in gene expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, CD11b, TNF-α, and CCL4 in both the AE and SI groups compared to the SC group, suggesting that while there were fewer microglia colonizing the hippocampus in both groups, the remaining cells are releasing increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Since there is evidence that astrocytes can also release cytokines (Choi et al., 2014) in response to alcohol in vitro (Blanco et al., 2005), the role of cytokine production in these cells should be investigated as an alternate source of neuroinflammatory signaling. The influence of some cytokines, such as CCL4, seems to be limited to the acute, local inflammatory response, while overexpression of other cytokines, such as IL-1β or TNF-α, can activate pro-apoptotic pathways (Denes et al., 2012; Hogquist et al., 1991; Bilbo & Schwarz, 2009; 2012). Cytokines can have profound effects on cell survival and neuroplasticity, as microglia play an important role in synapse maintenance. In particular, IL-1β is known to be a critical mediator of inflammation involved in cellular processes such as proliferation and apoptosis, with recent work demonstrating an important role for IL-1β in learning and memory (Bilbo & Schwarz, 2009; 2012). Furthermore, IL-1 can induce rapid suppression of the peripheral immune system (Weiss et al., 1989). Aberrant activation of IL-1β or other cytokines during development could contribute to both behavioral deficits and altered immune function in adulthood. Most of the recent neonatal literature, including current study, reports cytokine mRNA levels rather than levels of secreted protein (Drew et al., 2015; Topper et al., 2015). Research suggests that the correlation between cytokine mRNA and protein levels is not always strong and is dependent on the tissue type and cytokine analyzed (Zheng et al., 1991; Hirth et al., 2001). Most analysis of cytokines in the adult rodent brain have assessed protein levels (Marshall et al, 2013; McClain et al., 2011; Tiwari & Chopra, 2011), possibly due to the tissue requirement for successful protein analysis being greater than that needed for RT-PCR. However, future work could use enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which is more sensitive than other protein measures, to correlate protein and mRNA levels of cytokines in the neonatal brain.

Our model of alcohol exposure has been shown to impair long-term neuroplastic and behavioral outcomes related to learning and memory (Johnson & Goodlett, 2002; Klintsova et al., 2007; Hunt et al., 2009; Murawski et al., 2012; Thomas & Tran, 2012; Hamilton et al., 2010; 2011; 2012; 2014; Schreiber et al., 2013; Boschen et al., 2014), though the contribution of immune molecules to these deficits remains to be investigated. Microglia play an important role in synaptic pruning and maintenance, neurogenesis, and apoptosis, and the cytokines expressed by microglia, such as IL-1β, are important mediators of learning-related plasticity (Bilbo & Schwarz, 2009; 2012). During development and adulthood, these processes exist in a balance with optimal levels of cytokines resulting in peak learning performance; deviation from these optimal levels could impair synaptic transmission and maintenance, resulting in reduced long-term potentiation (LTP). Neonatal alcohol exposure has been shown to impair LTP in hippocampal CA1 (Puglia et al., 2010a, b), though a role for cytokines in this deficit has not been established. The long-term activation status of the microglia and cytokine expression in the alcohol-exposed brain must be investigated. Acknowledging neuroinflammation as a secondary source of damage following neonatal alcohol exposure opens up potential therapeutic possibilities which target the immune response.

Age of the alcohol exposure might play an important role in cytokine response, as previous studies of alcohol exposure in adolescent and adult rats found no change in TNF-α expression (Marshall et al, 2013; McClain et al., 2011; Zahr et al., 2010), while this cytokine was upregulated in the neonatal rodent cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum (Drew et al., 2015; Topper et al., 2015). IL-1β gene expression was also increased in all three brain regions in the study from Drew and colleagues (20150), while upregulation was only present in the cerebellum in the report by Topper et al., 2015, possibly due to differences in the exposure paradigm and time points used. Drew and colleagues (2015) also reported that CCL2 expression was increased only in hippocampus and cerebellum, showing region-specific profiles of cytokine release following alcohol exposure via intubation. Tiwari and Chopra (2011) found long-lasting increases in both TNF-α and IL-1β levels in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex on PD28 following PD7–9 alcohol exposure. Combined with the results of the current study, it is likely that cytokine expression is enhanced shortly following the alcohol exposure and remains elevated at least until adolescence, suggesting that alcohol-exposed animals may show other signs of central or peripheral immune dysfunction. Various types of stress have been shown to also affect release of cytokines through glucocorticoid signaling pathways, supporting the increase in cytokine seen in the SI group (Beutler et al., 1986; Minami et al., 1991; Elenkov et al., 1996).

The current study is one of the first to investigate gene expression levels of an anti-inflammatory cytokine following neonatal alcohol exposure. Expression of anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β was increased only in the AE group, suggesting compensatory processes in the brain to minimize long-term alcohol-induced damage through release of anti-inflammatory molecules. Microglia that release anti-inflammatory cytokines are thought to serve a neuroprotective role, and are thus classified as exhibiting an M2, or alternative, microglia phenotype as compared to the classic M1 phenotype associated with the pro-inflammatory response (Olah et al., 2011). Microglia with M2 classification fight inflammation through downregulation of pro-inflammatory factors and mediation of tissue repair (Varin & Gordon 2009). This response is a natural and necessary transition following M1 classical microglial activation and inflammation, continual production of pro-inflammatory cytokines can lead to continued neurotoxicity and cell death if not kept in check (Kigerl et al., 2009). Increased TGF-β gene expression might represent a neuroprotective immune response, as prolonged elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines induce apoptosis and tissue damage. Following an insult, TGF-β can reduce production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-2 and proliferation of T helper immune cells (Su et al., 2012). TGF-β is increased in the liver during alcohol-induced hepatic disease (Meyer et al., 2010; Gerjevic et al., 2012), but its role in the brain’s response to alcohol exposure has yet to be fully investigated. Recent work from the Valenzeula group (Topper et al., 2015) found no changes to TGF-β in the hippocampus and cerebellum of rats exposed to alcohol vapor during the neonatal period, possibly indicating an influence of route of administration or timing of analysis on the anti-inflammatory response. The results from our current study are in line with previous work in our lab has shown that our model of FASD increases bdnf gene expression and TrkB receptor protein levels (Boschen et al., 2015), which could indicate a neuroprotective response following neonatal alcohol exposure. The alcohol-specific effect on TGF- β compared to the classic pro-inflammatory cytokines which were upregulated in both AE and SI animals was very intriguing. Glucocorticoids have no effect on levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, suggesting that stress could play less of a role in TGF-β expression following an insult compared to pro-inflammatory molecule expression (Elenkov et al., 1996). Interestingly, levels of IL-10 were undetectable in the PD10 hippocampus when we attempted to assess this cytokine in this study, supporting other literature in human infants showing that the anti-inflammatory response is immature in the neonatal brain and IL-10 might not play a large role in the brain’s neuroimmune response during development (Schultz et al., 2004). Recent work by Topper et al., 2015 measured levels of IL-10 in the hippocampus and cerebellum in neonatal animals following exposure to alcohol vapor and found no changes in either brain region. However, increased levels of IL-10 have been reported following severe sepsis in human neonates (Ng et al., 2003), indicating that IL-10 response might be restricted to the most severe immune challenges or infections.

Along with other recent work from our lab (Boschen et al., 2015), the current study shows that the short-term effects of the alcohol exposure and sham-intubation overlap more than previously realized. As discussed above, our lab has shown that both AE and SI groups have elevated plasma corticosterone levels on PD10 (Boschen et al., 2015). Additionally, we reported that both AE and SI groups have increased hippocampal BDNF protein and total gene expression levels on PD10, though exon I-specific bdnf gene expression and levels of TrkB protein are specifically increased in AE animals alone. Combined with the current study, these data suggest that alcohol exposure and sham-intubation can impact the brain similarly on short-term measures that respond to stress as well as alcohol exposure. However, our findings do not necessarily indicate that stress is the driving force behind these overlapping effects. Instead, it is more likely that both alcohol exposure and sham-intubation activate the neuroinflammatory response, which presents in a similar way independent of the cause (ex. drug exposure, stress, pollution, viral infection). Early life stress has been shown to alter cytokine expression in the neonatal and adult brain. Specifically, two studies using maternal separation stress from PD1–14 showed increased IL-1β concentrations in hippocampus on PD16 (no reported changes to IL-6 and TNF-α) (Roque et al., in press) and upregulation of both IL-10 and TNF-α in the adult hippocampus (Pinheiro et al., 2015). Interestingly, this manipulation increased microglial activation and decreased number of astrocytes in the neonatal hippocampus (Roque et al., in press). Both studies show that early life stress paradigms can increase levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, dependent on cytokine and timing of tissue analysis. In the current study, both the AE and SI groups show increased levels of plasma corticosterone, indicating that stress likely contributes to the overlapping effects, but the number of effects unique to alcohol exposure (in this study, microglial cell territory and increased expression of CCL4 and TGF-β) discount stress as the sole factor driving the neuroinflammatory response in our model.

4.1 Conclusion

The current study found that in a rodent model of drinking during the third trimester of pregnancy, alcohol exposure on PD4–9 significantly decreases microglial cell number, decreases microglia cell territory indicating enhanced activation, increases pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine gene expression in the hippocampus on PD10. How long the neuroimmune activation persists following cessation of the alcohol exposure is not known; current work in our lab is pursuing this line of research. Furthermore, how glucocorticoid activation interacts with the neuroimmune response in the current study remains to be elucidated. The interaction between the immune system and cognitive function is still being explored, but current evidence supports that alcohol’s effects on microglia and cytokine production could have a significant impact on alcohol-related deficits in learning and memory, particularly if there is long-term dysregulation of the immune response or if the individual is faced with another immune challenge later in life. Investigation of long-term neuroimmune function following neonatal alcohol exposure and the effect on cognitive and behavioral outcomes is an essential next step. Importantly, further insults, such as exposure to alcohol or infection during adulthood, would give important information regarding whether early aberrant microglial activation primes later abnormal immune function. In summary, these data add important information regarding developing immune system and how microglia in the neonatal brain respond to teratogens, such as alcohol exposure.

Highlights.

We use a rat model of third trimester-equivalent binge alcohol exposure.

We investigated microglia number and activation state in the neonatal hippocampus.

Both neonatal alcohol and intubation decreased microglial number in CA1 and dentate gyrus.

Neonatal alcohol decreased cell territory in CA1, CA3 and dentate gyrus due to increased microglia activation.

Alcohol increased expression of cytokines CCL4 and TGF-β, while alcohol and intubation both increased IL-1β, TNF-α and CD11b.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank J.M. Schwarz for the use of cytokine primers, T.L. Roth for the use of RT-PCR equipment, Z. Hussain and S. Shareeq for assistance with spectrophotometry and gel electrophoresis, and all the undergraduate assistants for their help with animal generation and care. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/NIGMS COBRE: The Delaware Center for Neuroscience Research 1P20GM103653 – 01A1 to AYK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Karen E. Boschen, Email: kboschen@psych.udel.edu.

Michael J. Ruggiero, Email: mruggiero@psych.udel.edu.

Anna Y. Klintsova, Email: aklintsova@psych.udel.edu.

References

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the royal statistical society. Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B, Krochin N, Milsark IW, Luedke C, Cerami A. Control of cachectin (tumor necrosis factor) synthesis: mechanisms of endotoxin resistance. Science (New York, NY) 1986;232:977–980. doi: 10.1126/science.3754653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. Early-life programming of later-life brain and behavior: a critical role for the immune system. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2009;3:14. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.014.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 2012;33:267–286. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco AM, Valles SL, Pascual M, Guerri C. Involvement of TLR4/type I IL-1 receptor signaling in the induction of inflammatory mediators and cell death induced by ethanol in cultured astrocytes. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2005;175:6893–6899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaze J, Roth TL. Exposure to caregiver maltreatment alters expression levels of epigenetic regulators in the medial prefrontal cortex. International journal of developmental neuroscience : the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience. 2013;31:804–810. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschen KE, Criss KJ, Palamarchouk V, Roth TL, Klintsova AY. Effects of developmental alcohol exposure vs. intubation stress on BDNF and TrkB expression in the hippocampus and frontal cortex of neonatal rats. International journal of developmental neuroscience : the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience. 2015;43:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschen KE, Hamilton GF, Delorme JE, Klintsova AY. Activity and social behavior in a complex environment in rats neonatally exposed to alcohol. Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY) 2014;48:533–541. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus J, Moller T, Kettenmann H. Phagocytozing ameboid microglial cells studied in a mouse corpus callosum slice preparation. Glia. 1996;16:81–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199601)16:1<81::AID-GLIA9>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Pan ZL, Pang Y, Evans OB, Rhodes PG. Cytokine induction in fetal rat brains and brain injury in neonatal rats after maternal lipopolysaccharide administration. Pediatric research. 2000;47:64–72. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASDs) 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chan WY, Kohsaka S, Rezaie P. The origin and cell lineage of microglia: new concepts. Brain research reviews. 2007;53:344–354. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SS, Lee HJ, Lim I, Satoh J, Kim SU. Human astrocytes: secretome profiles of cytokines and chemokines. PloS one. 2014;9:e92325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debruin EJ, Hughes MR, Sina C, Lu A, Cait J, Jian Z, Lopez M, Lo B, Abraham T, McNagny KM. Podocalyxin regulates murine lung vascular permeability by altering endothelial cell adhesion. PloS one. 2014;9:e108881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denes A, Lopez-Castejon G, Brough D. Caspase-1: is IL-1 just the tip of the ICEberg? Cell death & disease. 2012;3:e338. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early human development. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew PD, Johnson JW, Douglas JC, Phelan KD, Kane CJ. Pioglitazone blocks ethanol induction of microglial activation and immune responses in the hippocampus, cerebellum, and cerebral cortex in a mouse model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2015;39:445–454. doi: 10.1111/acer.12639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew PD, Kane CJM. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders and Neuroimmune Changes. International review of neurobiology. 2014;118:41–80. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801284-0.00003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov IJ, Papanicolaou DA, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP. Modulatory effects of glucocorticoids and catecholamines on human interleukin-12 and interleukin-10 production: clinical implications. Proceedings of the Association of American Physicians. 1996;108:374–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu R, Shen Q, Xu P, Luo JJ, Tang Y. Phagocytosis of microglia in the central nervous system diseases. Molecular neurobiology. 2014;49:1422–1434. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganter S, Northoff H, Mannel D, Gebicke-Harter PJ. Growth control of cultured microglia. Journal of neuroscience research. 1992;33:218–230. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490330205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann J, Banati RB, Wiessner C, Hossmann KA, Kreutzberg GW. Reactive microglia in cerebral ischaemia: an early mediator of tissue damage? Neuropathology and applied neurobiology. 1995;21:277–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1995.tb01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerjevic LN, Liu N, Lu S, Harrison-Findik DD. Alcohol Activates TGF-Beta but Inhibits BMP Receptor-Mediated Smad Signaling and Smad4 Binding to Hepcidin Promoter in the Liver. International journal of hepatology. 2012;2012:459278. doi: 10.1155/2012/459278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, Mehler MF, Conway SJ, Ng LG, Stanley ER, Samokhvalov IM, Merad M. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science (New York, NY) 2010;330:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett CR, Eilers AT. Alcohol-induced Purkinje cell loss with a single binge exposure in neonatal rats: a stereological study of temporal windows of vulnerability. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1997;21:738–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ. Stereology of arbitrary particles. A review of unbiased number and size estimators and the presentation of some new ones, in memory of William R. Thompson. Journal of microscopy. 1986;143:3–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton GF, Boschen KE, Goodlett CR, Greenough WT, Klintsova AY. Housing in environmental complexity following wheel running augments survival of newly generated hippocampal neurons in a rat model of binge alcohol exposure during the third trimester equivalent. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2012;36:1196–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton GF, Jablonski SA, Schiffino FL, St Cyr SA, Stanton ME, Klintsova AY. Exercise and environment as an intervention for neonatal alcohol effects on hippocampal adult neurogenesis and learning. Neuroscience. 2014;265:274–290. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton GF, Murawski NJ, St Cyr SA, Jablonski SA, Schiffino FL, Stanton ME, Klintsova AY. Neonatal alcohol exposure disrupts hippocampal neurogenesis and contextual fear conditioning in adult rats. Brain research. 2011;1412:88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton GF, Whitcher LT, Klintsova AY. Postnatal binge-like alcohol exposure decreases dendritic complexity while increasing the density of mature spines in mPFC Layer II/III pyramidal neurons. Synapse (New York, NY) 2010;64:127–135. doi: 10.1002/syn.20711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirth A, Skapenko A, Kinne RW, Emmrich F, Schulze-Koops H, Sack U. Cytokine mRNA and protein expression in primary-culture and repeated-passage synovial fibroblasts from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis research. 2002;4:117–125. doi: 10.1186/ar391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogquist KA, Nett MA, Unanue ER, Chaplin DD. Interleukin 1 is processed and released during apoptosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:8485–8489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt PS, Jacobson SE, Torok EJ. Deficits in trace fear conditioning in a rat model of fetal alcohol exposure: dose-response and timing effects. Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY) 2009;43:465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, Bittigau P, Ishimaru MJ, Wozniak DF, Koch C, Genz K, Price MT, Stefovska V, Horster F, Tenkova T, Dikranian K, Olney JW. Ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration and fetal alcohol syndrome. Science (New York, NY) 2000;287:1056–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TB, Goodlett CR. Selective and enduring deficits in spatial learning after limited neonatal binge alcohol exposure in male rats. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2002;26:83–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane CJ, Phelan KD, Han L, Smith RR, Xie J, Douglas JC, Drew PD. Protection of neurons and microglia against ethanol in a mouse model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2011;(25 Suppl 1):S137–S145. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:13435–13444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klintsova AY, Helfer JL, Calizo LH, Dong WK, Goodlett CR, Greenough WT. Persistent impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis in young adult rats following early postnatal alcohol exposure. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2007;31:2073–2082. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (San Diego, Calif) 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SA, McClain JA, Kelso ML, Hopkins DM, Pauly JR, Nixon K. Microglial activation is not equivalent to neuroinflammation in alcohol-induced neurodegeneration: The importance of microglia phenotype. Neurobiology of disease. 2013;54:239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Kalberg WO, Robinson LK, Buckley D, Manning M, Hoyme HE. Prevalence and epidemiologic characteristics of FASD from various research methods with an emphasis on recent in-school studies. Developmental disabilities research reviews. 2009;15:176–192. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClain JA, Morris SA, Deeny MA, Marshall SA, Hayes DM, Kiser ZM, Nixon K. Adolescent binge alcohol exposure induces long-lasting partial activation of microglia. Brain, behavior, and immunitySuppl. 2011;(25 Suppl 1):S120–S128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer C, Meindl-Beinker NM, Dooley S. TGF-beta signaling in alcohol induced hepatic injury. Frontiers in bioscience (Landmark edition) 2010;15:740–749. doi: 10.2741/3643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer U, Feldon J, Schedlowski M, Yee BK. Immunological stress at the maternal-foetal interface: a link between neurodevelopment and adult psychopathology. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2006;20:378–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on the development of cerebral cortex: I. Neuronal generation. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1988;12:440–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami M, Kuraishi Y, Yamaguchi T, Nakai S, Hirai Y, Satoh M. Immobilization stress induces interleukin-1 beta mRNA in the rat hypothalamus. Neurosci Lett. 1991;123:254–256. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90944-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney SM, Napper RM, West JR. Long-term effect of postnatal alcohol exposure on the number of cells in the neocortex of the rat: a stereological study. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1996;20:615–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murawski NJ, Klintsova AY, Stanton ME. Neonatal alcohol exposure and the hippocampus in developing male rats: effects on behaviorally induced CA1 c-Fos expression, CA1 pyramidal cell number, and contextual fear conditioning. Neuroscience. 2012;206:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann H, Kotter MR, Franklin RJ. Debris clearance by microglia: an essential link between degeneration and regeneration. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2009;132:288–295. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Li K, Wong RP, Chui K, Wong E, Li G, Fok TF. Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine responses in preterm infants with systemic infections. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition. 2003;88:F209–F213. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.3.F209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science (New York, NY) 2005;308:1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon K, Kim DH, Potts EN, He J, Crews FT. Distinct cell proliferation events during abstinence after alcohol dependence: microglia proliferation precedes neurogenesis. Neurobiology of disease. 2008;31:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olah M, Biber K, Vinet J, Boddeke HW. Microglia phenotype diversity. CNS & neurological disorders drug targets. 2011;10:108–118. doi: 10.2174/187152711794488575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro RM, de Lima MN, Portal BC, Busato SB, Falavigna L, Ferreira RD, Paz AC, de Aguiar BW, Kapczinski F, Schroder N. Long-lasting recognition memory impairment and alterations in brain levels of cytokines and BDNF induced by maternal deprivation: effects of valproic acid and topiramate. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996) 2015;122:709–719. doi: 10.1007/s00702-014-1303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posillico CK, Schwarz JM. An investigation into the effects of antenatal stressors on the postpartum neuroimmune profile and depressive-like behaviors. Behavioural brain research. 2015;298:218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglia MP, Valenzuela CF. Ethanol acutely inhibits ionotropic glutamate receptor-mediated responses and long-term potentiation in the developing CA1 hippocampus. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2010;34:594–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglia MP, Valenzuela CF. Repeated third trimester-equivalent ethanol exposure inhibits long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region of neonatal rats. Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY) 2010;44:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roque A, Ochoa-Zarzosa A, Torner L. Maternal separation activates microglial cells and induces an inflammatory response in the hippocampus of male rat pups, independently of hypothalamic and peripheral cytokine levels. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth TL, Lubin FD, Funk AJ, Sweatt JD. Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene. Biological psychiatry. 2009;65:760–769. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Chakraborty G, Mao RF, Paik SM, Vadasz C, Saito M. Tau phosphorylation and cleavage in ethanol-induced neurodegeneration in the developing mouse brain. Neurochemical research. 2010;35:651–659. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-0116-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson PD, Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Little RE, Clarren SK, Dehaene P, Hanson JW, Graham JM., Jr Incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome and prevalence of alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder. Teratology. 1997;56:317–326. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199711)56:5<317::AID-TERA5>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber WB, St Cyr SA, Jablonski SA, Hunt PS, Klintsova AY, Stanton ME. Effects of exercise and environmental complexity on deficits in trace and contextual fear conditioning produced by neonatal alcohol exposure in rats. Developmental psychobiology. 2013;55:483–495. doi: 10.1002/dev.21052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz C, Temming P, Bucsky P, Gopel W, Strunk T, Hartel C. Immature anti-inflammatory response in neonates. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2004;135:130–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CC, Guevremont D, Williams JM, Napper RM. Apoptotic cell death and temporal expression of apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bax in the hippocampus, following binge ethanol in the neonatal rat model. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2015;39:36–44. doi: 10.1111/acer.12606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stence N, Waite M, Dailey ME. Dynamics of microglial activation: A confocal time-lapse analysis in hippocampal slices. Glia. 2001;33:256–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su DL, Lu ZM, Shen MN, Li X, Sun LY. Roles of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of SLE. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology. 2012;2012:347141. doi: 10.1155/2012/347141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JD, Tran TD. Choline supplementation mitigates trace, but not delay, eyeblink conditioning deficits in rats exposed to alcohol during development. Hippocampus. 2012;22:619–630. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari V, Chopra K. Resveratrol prevents alcohol-induced cognitive deficits and brain damage by blocking inflammatory signaling and cell death cascade in neonatal rat brain. Journal of neurochemistry. 2011;117:678–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topper LA, Baculis BC, Valenzuela CF. Exposure of neonatal rats to alcohol has differential effects on neuroinflammation and neuronal survival in the cerebellum and hippocampus. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12 doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0382-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urakubo A, Jarskog LF, Lieberman JA, Gilmore JH. Prenatal exposure to maternal infection alters cytokine expression in the placenta, amniotic fluid, and fetal brain. Schizophrenia research. 2001;47:27–36. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varin A, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: immune function and cellular biology. Immunobiology. 2009;214:630–641. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RJ, Colivicchi MA, Allen R, Schol F, Lallemand F, de Witte P, Ballini C, Corte LD, Dexter D. Neuro-inflammation induced in the hippocampus of 'binge drinking' rats may be mediated by elevated extracellular glutamate content. Journal of neurochemistry. 2009;111:1119–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JM, Sundar SK, Becker KJ, Cierpial MA. Behavioral and neural influences on cellular immune responses: effects of stress and interleukin-1. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 1989;(50 Suppl):43–53. discussion 54-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahr NM, Luong R, Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A. Measurement of serum, liver, and brain cytokine induction, thiamine levels, and hepatopathology in rats exposed to a 4-day alcohol binge protocol. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2010;34:1858–1870. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng RQH, Abney E, Chu CQ, Field M, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Maini RN, Feldmann M. Detection of interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 production in human thyroid epithelial cells by non-radioactive in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical methods. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 1991;83:314–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]