Abstract

Neuropeptides produced from prohormones by selective action of endopeptidases are vital signaling molecules, playing a critical role in a variety of physiological processes, such as addiction, depression, pain, and circadian rhythms. Neuropeptides bind to post-synaptic receptors and elicit cellular effects like classical neurotransmitters. While each neuropeptide could have its own biological function, mass spectrometry (MS) allows for the identification of the precise molecular forms of each peptide without a priori knowledge of the peptide identity and for the quantitation of neuropeptides in different conditions of the samples. MS-based neuropeptidomics approaches have been applied to various animal models and conditions to characterize and quantify novel neuropeptides, as well as known neuropeptides, advancing our understanding of nervous system function over the past decade. Here, we will present an overview of neuropeptides and MS-based neuropeptidomic strategies for the identification and quantitation of neuropeptides.

Keywords: identification, mass spectrometry, neuropeptides, peptidomics, quantitation

Introduction

Neuropeptides, which signal between neurons, are known to be involved in a variety of physiological processes, including addiction, depression, hunger, pain, fear, anxiety, and circadian rhythms [1,2]. Neuropeptides are 3–100 amino acid residues long and up to 50 times larger than classic neurotransmitters [3]. The term "neuropeptides" was first introduced by De Wied [4] in 1971 to describe an endogenous peptide synthesized in nerve cells. While peptide hormones are also considered important intercellular signaling molecules, there are differences between neuropeptides and peptide hormones. That is, neuropeptides are secreted from neuronal cells (primarily neurons but also glia for some peptides) and signal to neighboring cells (primarily neurons), whereas peptide hormones are secreted from neuroendocrine cells and act on distant tissues by traveling through the blood [2,5]. Approximately 100 different neuropeptides are currently known to function in cell-to-cell signaling (http://www.neuropeptides.nl). Neuropeptides bind to post-synaptic receptors and elicit cellular responses like classical neurotransmitters.

Neuropeptide Synthesis

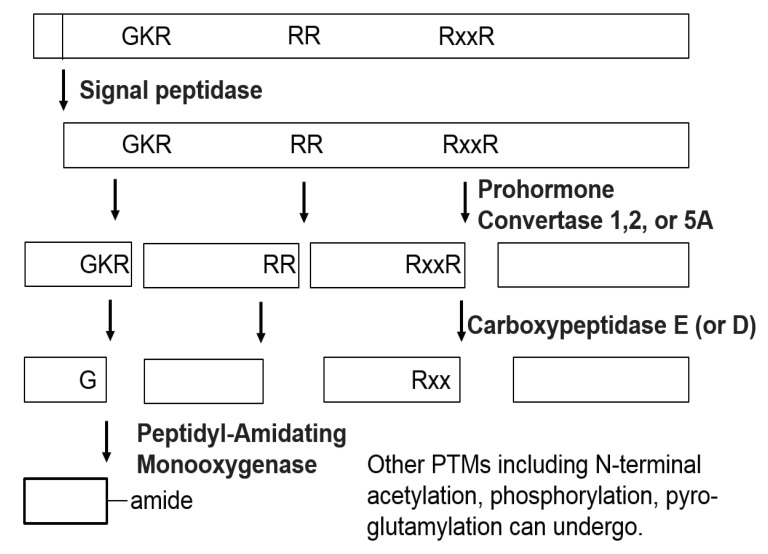

Neuropeptides are produced from precursor proteins (or prohormones) by a series of enzymatic processing steps. The neuropeptide precursors generally do not have functions on their own, requiring processing to generate the active forms. The precursors are synthesized on ribosomes at the endoplasmic reticulum and processed through the Golgi [5]. When the NH2-terminal signal peptide of the neuropeptide precursors is cleaved by signal peptidase, the precursors are routed to the Golgi apparatus and packaged into dense-core secretory vesicles together with processing proteases, termed convertases. Most neuropeptide precursors are first processed by endopeptidases, including prohormone convertase 1 (also known as prohormone convertase 3) and prohormone convertase 2 and, to a lesser extent, prohormone/proprotein convertase 5A (also known as prohormone/proprotein convertase 6A) [6]. The endopeptidases typically cleave at pairs of basic amino acids, usually Lys-Arg (KR) or Arg-Arg (RR) sites, but on occasion, the basic amino acids are separated by 2, 4, or 6 other amino acids (Fig. 1). The next stage of processing is the removal of C-terminal basic residues in the mature secretory vesicle. Carboxypeptidase E is the exopeptidase primarily responsible for removing the C-terminal basic residues, and carboxypeptidase D has also been shown to act in this role. After removal of the C-terminal basic residues, other enzymes perform additional post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as amidation, acetylation, phosphorylation, sulfation, and glycosylation [6]. For example, peptides with a C-terminal glycine are typically converted to the amide by peptidyl-α-amidating monooxygnenase [7], and tyrosine sulfation is known to be mediated by tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase [8]. These final bioactive forms of the peptides are stored within secretory vesicles that are accumulated within the cells. When the cells are stimulated, the secretory vesicles are known to fuse with the cellular membrane to release the neuropeptides into the extracellular environment [2]. The secreted neuropeptides can interact with receptors containing specific binding sites. The receptors are often G-protein-coupled receptors. The interaction of the neuropeptides with the receptors causes a conformational change in the receptor, resulting in the production of a cellular response through a variety of mechanisms, depending on the type of receptor.

Fig. 1. Bioactive neuropeptide synthesis. Adopted from Fricker et al. Mass Spectrom Rev 2006;25:327-344, with permission of John Wiley and Sons [6]. A hypothetical precursor is shown to contain typical processing sites of Lys-Arg (KR), Arg-Arg (RR), or R-Xn-R, where n = 2, 4, or 6. First, a signal peptidase in the endoplasmic reticulum removes the N-terminal signal peptide, and the precursor is routed to the Golgi apparatus and packaged into dense-core secretory vesicles. The prohormone convertase 1, 2, or 5A cleaves the precursor to produce intermediates that contain C-terminal K and/or R residues. Those basic residues are removed by carboxypeptidase E (or D). After removal of the basic residues, peptides with a C-terminal glycine are typically converted to the amide by peptidyl-glycine α-amidating monooxygenase. In addition, a number of other post-translational modifications (PTMs), including N-terminal acetylation, phosphorylation, and pyroglutamylation, have been reported.

While a single neuropeptide precursor often produces multiple neuropeptides, the proteolytic processing of the precursor protein occurs in a tissue-specific and even region-specific manner. A classic example is the processing of the precursor proopiomelanocortin in the pituitary. In the anterior lobe of the pituitary, the precursor is converted into adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which binds to several subtypes of melanocortin receptors, such as MC2R, located in the adrenal gland; this receptor controls the production of glucocorticoids (cortisol) [9,10]. In the intermediate lobe of the pituitary and also in the brain, ACTH is further processed into alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, which binds to melanocortin receptors with completely different affinities [11]. The PTMs can also regulate the bioactivity and stability of the neuropeptides and therefore affect the binding affinities of the neuropeptides for the receptors. For example, acetylation of the N-terminus of β-endorphin removes the ability of the peptide to stimulate opioid receptors and to produce analgesia [6]. Conversely, octanoylation of the peptide ghrelin on a serine residue is essential for the binding of the peptide to its receptor [12]. Although the various aspects of peptide synthesis, including PTMs, lead to an increase in neuropeptide complexity, unveiling new peptides and unreported peptide properties is critical to advancing our understanding of nervous system function.

Clinical Importance of Neuropeptides

While neuropeptides are involved in a wide range of physiological processes, including hunger, food intake, body weight regulation, and circadian rhythms, it has been shown that dysregulation of neuropeptides often results in a variety of neurological disorders [13,14,15]. Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures. Neuropeptides, such as arginine-vasopressin, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), enkephalin, β-endorphin, pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), and tachykinins, were shown to have proconvulsive effects, whereas other neuropeptides, like ACTH, angiotensin, cholecystokinin, somatostatin, and thyrotropin-releasing hormone, were able to suppress seizures in the brain [16]. In addition, neuropeptides, such as dynorphin and substance P, were shown to be involved in the pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease, which is a neurodegenerative disease with motor and non-motor symptoms [17]. Progression to addiction is also known to be influenced by several peptidergic neuromodulators. A few orexigenic neuropeptides, including galanin, enkephalin, and orexin/hypocretin, were shown to have a positive feedback relationship to alcohol, while other hypothalamic neuropeptides, such as dynorphin, CRF, and melanocortins, showed a negative feedback relationship to alcohol intake. Dysregulation of these multiple neuropeptides is assumed to result in alcohol addiction [18]. There was also a report that neuropeptides, such as substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptides, vasoactive intestinal peptide/PACAP, and neuropeptide Y (NPY), are associated with regulation of cutaneous immune responses and tissue maintenance and repair. Due to these diverse functions of neuropeptides, neuropeptides and neuropeptide receptors have been drug targets for the treatment of neurological disorders [3,19].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Neuropeptidomics

Traditional methods of neuropeptide analysis

Traditionally, the analysis of neuropeptides was performed by Edman sequencing, in which the N-terminal amino acid is sequentially removed. The method was developed by Edman in 1950 and is used for neuropeptide sequencing in many different species—for example, NPY in the porcine brain [20] and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the dogfish brain [21]. However, analysis by this method is slow and does not allow for the sequencing of neuropeptides containing N-terminal PTMs [22]. Immunological techniques, such as radioimmunoassay (RIA) and immunohistochemistry (IHC), have been used for measuring relative neuropeptide levels and spatial localization. RIA has been a popular tool to quantify neuropeptides in biological samples, such as NPY [23] and galanin in the rat brain [24]. Although RIA is a relatively sensitive technique capable of absolute quantification of peptide levels, it is not always specific for a single-peptide form because of its antibody-based detection method. In addition, unless specific antibodies are available for the different isoforms, RIAs do not distinguish between these modifications. IHC has provided essential information regarding the localization of neuropeptides within the complexity of the brain structure, improving our understanding of the distribution of peptides. However, IHC does not report the actual size or full identity of the peptide, including PTMs. In addition, these antibody-based methods require a priori knowledge of a potential neuropeptide in order to generate antibodies specific to the neuropeptides and only detect peptide sequences with known structures.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Peptidomics

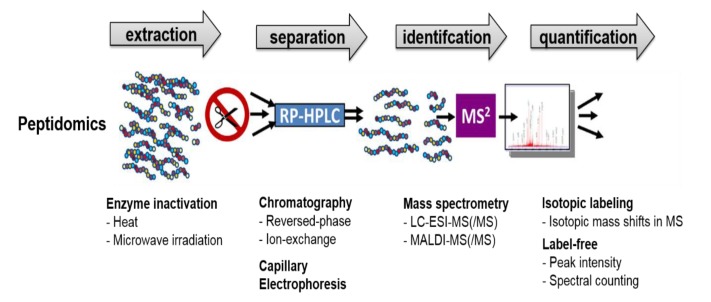

In contrast to immuno-based methods, mass spectrometry (MS) enables one to detect and identify the precise forms of neuropeptides without a priori knowledge of the peptide's identity, resulting in the identification of previously unknown neuropeptides. MS has been used to identify and characterize hundreds of endogenous peptides in various animals [25,26,27,28,29]. The high-throughput discovery of neuropeptides based on MS has made up the field of peptidomics (Fig. 2) [6,30,31,32,33]. While typical proteomic analysis involves the digestion of proteins using proteases, such as trypsin, to generate peptides that can be readily sequenced by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), peptidomics focuses on the analysis of the native peptide forms, including PTMs, without using digestive enzymes. Therefore, it is important to identify and characterize as many neuropeptides as possible, because each peptide can have its own biological function. While MS-based peptidomics can be utilized to characterize a large number of neuropeptides simultaneously, it can be also applied to the quantification of individual neuropeptides.

Fig. 2. Overall workflow of mass spectrometry (MS)-based peptidomics. Adopted from Schrader et al. EuPA Open Proteom 2014;3:171-182, according to Creative Commons License [33]. Peptidomics focuses on analyzing endogenous peptides that are present in biological samples, including brain tissue. In contrast to bottom-up proteomics studies that involve proteolytic digestion, it is important to minimize the activity of proteases that may be present in the samples via heat or microwave irradiation prior to peptide extraction in the peptidomics experiments. While the extracted peptides can be analyzed directly by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)-MS, they are often separated by reversed-phase chromatography or capillary electrophoresis in order to reduce sample complexity. Then, the peptides are analyzed by MS in order to obtain amino acid sequence information of the peptides without a priori knowledge. RP-HPLC, reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography; LC-ESI-MS, liquid chromatography electrospray ionization mass spectrometry.

Sample Preparation for Peptidomics Experiment

Although MS allows the identification of a large number of neuropeptides in a high-throughput manner, sample preparation prior to MS is a critical step that affects peptide identification coverage in peptidomics experiments. When the animal is sacrificed and the brain tissue of interest is obtained, proteases rapidly degrade larger proteins into smaller peptides that fall into the mass range of neuropeptides. The presence of degraded products derived from highly abundant proteins often complicates the MS analysis and interferes with the identification of less abundant neuropeptides. Different techniques, including focused microwave irradiation before decapitation, microwave irradiation after decapitation, and boiling the tissue immediately after decapitation, have been used in order to inactivate the proteases responsible for the high background of protein degradation fragments [32,34,35,36,37,38]. In addition to the procedures of protease deactivation, peptide extraction and subsequent treatment are other steps that affect the number of identified neuropeptides. The use of different solvents and procedures can affect the peptide profiles detectable in brain tissue. Che et al. [31] compared different extraction conditions for the recovery of neuropeptides from mouse hypothalamus. They found that sonication and heating in water (70℃ for 20 min), followed by cold acid and centrifugation, enabled the efficient extraction of many neuropeptides without the formation of the protein degradation fragments seen with hot acid extractions. Bora et al. [39] and Lee et al. [37] also showed that multiple stages of peptide extraction, including boiling water, acidified acetone, and acetic acid, were able to maximize the number of identified neuropeptides from their respective analyses of supraoptic nucleus and suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) samples in the rat brain.

MS Analysis

After sample processing, the extracted peptides are subjected to MS analysis. A mass spectrometer consists of an ionization source, a mass analyzer separating the ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), and a detector recording the number of ions at each m/z value. Two commonly used types of ionization are electrospray ionization (ESI) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI). While each approach has its own advantages, MALDI is more tolerant to the presence of salts. Thus, MALDI is often applied to direct tissue profiling or molecular ion imaging from tissue sections. Direct tissue sample analysis by MALDI-based MS is usually performed by a simple sequence of steps, which include placing the tissue of interest on the MALDI plate, applying a droplet of matrix, and irradiating the co-crystallized tissue to cause desorption/ionization of the peptides [30]. MALDI imaging provides valuable information pertaining to the spatial localization of neuropeptides [40]. Although MALDI-MS can be interfaced with separation strategies, such as liquid chromatography (LC) and capillary electrophoresis, ESI-MS can be coupled more easily with the separation methods, because the ions are produced as an aerosol from the liquid phase with a high voltage in ESI. The introduction of a nano-electrospray, based on capillary LC, coupled to MS, significantly increases the sensitivity in LC-ESI-MS, and furthermore, the preferred formation of multiple-charge states in ESI allows for more comprehensive MS/MS fragmentation data.

MS Data Analysis for Neuropeptide Identification

While neuropeptides can be identified by comparing experimental peptide masses obtained from MS data against a list of known neuropeptide masses, they are typically identified with both MS and MS/MS fragmentation data. While collision-induced dissociation is widely used for peptide identification, other fragmentation methods, such as higher energy collision dissociation and electron transfer dissociation, have recently improved the identification capability of peptides and PTM localization [41,42,43]. The automated identification of neuropeptides based on their MS and MS/MS data is pursued by using proteomic-based search engines, such as Mascot, SEQUEST, X!Tandem, Peaks Studio, and ProSightPC [37,44,45,46,47]. Since peptidomics searches typically employ criteria, such as no enzymatic cleavage and various common modifications (e.g., N-terminal acetylation and C-terminal amidation), they often require a larger search space and longer search times for peptide identification. Several neuropeptide prohormone databases, including SwePep, have been constructed to facilitate neuropeptide identification, and cleavage prediction programs, such as NeuroPred, were developed to predict cleavage sites in prohormones and to provide the masses of the resulting peptides [48,49]. In addition to the database search strategies, neuropeptides can be also identified by de novo sequencing, especially when the species of interest does not have a sequenced genome. While peptide spectra are compared with theoretical peptides in the database search strategy, de novo sequencing, which is the direct assignment of the amino acid sequence from the MS/MS spectrum, can be pursued when the database is not available. Although de novo sequencing can be performed manually, the process is labor-intensive and time-consuming. There are several software packages that can perform de novo sequencing directly on MS/MS data, including Lutefisk (http://www.hairyfatguy.com/lutefisk/), Mascot Distiller (Matrix Science), and PEAKS (Bioinformatics Solutions, http://www.bioinformaticssolutions.com/) [30]. The peptide sequences obtained from de novo sequencing are often compared with the nonredundant database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information to establish the peptide identities with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). The BLAST search compares a partial neuropeptide sequence against the database of a closely related species.

Quantitative Neuropeptidomics

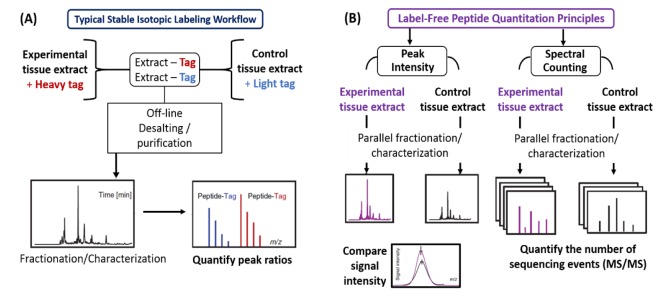

MS-based peptidomic techniques allow for measuring relative levels of peptides in different conditions of the samples, as well as peptide identification. Quantitation of peptides based on MS is generally achieved either by stable isotope labeling or label-free approaches (Fig. 3) [50,51]. In stable isotope labeling, the relative levels of peptides in two different samples are typically examined by labeling the peptides in one sample with a light stable isotope and those in the other sample with a heavy stable isotope; the two samples are then combined and analyzed together. The relative levels of the peptides are calculated by the difference in the MS peaks (peak intensity or peak area) of the two samples. While the stable isotopes can be introduced to the peptides either metabolically or through chemical reactions, isotope labeling through chemical reactions enables one to obtain quantitative information from biological samples, such as brain tissues, for which metabolic labeling is not available. A number of different isotopic tags, including acetic anhydride, succinic anhydride, and trimethylammonium butyrate (TMAB), have been used for quantitative analyses of endogenous peptides in various samples and conditions [6,34,52]. For example, the TMAB tag was used to evaluate the relative changes of endogenous peptides in response to food intake or drug treatment [53,54,55] and to assess the role of protein convertase 1/3 and 2 in the processing of the peptides in mouse models [56,57]. In label-free methods, each sample is prepared separately and then subjected directly to individual LC-MS or LC-MS/MS runs, followed by comparisons of either the mass spectral peak intensities of the detected peptides or the total number of MS/MS spectra identified for a peptide, called spectral counting [51]. Since there is no limit to the number of samples that can be compared, label-free quantitation allows for the comparison of multiple samples or conditions. The approach has been used to measure the changes in the levels of neuropeptides present during the daytime and nighttime in the rat SCN [58,59] and to examine the expression changes of endogenous peptides involved in the embryogenesis of Japanese quail brains [60] and the nucleus accumbens of morphine-dependent rats [61]. In addition, quantitative peptidomic analyses based on peak intensities has enabled us to discover endogenous peptides associated with repeated exposure to amphetamine and with individual variations in sensitivity to the behavioral effects of cocaine in rat models [62,63].

Fig. 3. Workflow of mass spectrometry (MS)-based quantitation of endogenous peptides. Romanova et al. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2013;17:801-808, with permission of Elsevier [51]. Quantitation of endogenous peptides based on MS is generally achieved either by stable isotope labeling (A) or label-free approaches (B). In stable isotope labeling, the endogenous peptides in two different samples are labeled with either a light stable isotope or a heavy stable isotope, and the two samples are then combined and analyzed together. The relative levels of the peptides are calculated by the difference in the MS peaks (peak intensity or peak area) of the two samples. In label-free quantitation, each sample is prepared separately and then subjected to individual liquid chromatography (LC)-MS or LC–tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) runs, followed by comparisons of either the mass spectral peak intensities of the detected peptides or the total number of MS/MS spectra identified for a peptide, called spectral counting.

Conclusion

Neuropeptides are important signaling molecules that are involved in many kinds of physiological processes, including addiction, depression, mood regulation, and circadian rhythms. Because of their biological significance, neuropeptides have become key targets in drug discovery. While immunological techniques, such as RIA and IHC, require a priori knowledge of neuropeptides and only detect peptide sequences with known structures, MS enables one to detect and identify the precise forms of neuropeptides without a priori knowledge of peptide identity, resulting in the identification of previously unknown neuropeptides. In addition, MS-based quantitative analyses of neuropeptides based on either stable isotope labeling or label-free methods provide information on the relative levels of neuropeptides in different physiological conditions, which can be helpful in understanding the function of the neuropeptides. Continuous efforts to implement current MS-based peptidomics techniques for neuropeptide identification and quantitation are expected to provide more profound insights into the neurochemical communication of neurons in various physiological processes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Brain Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2015M3C7A1064795) and the KIST institutional program.

References

- 1.Hökfelt T, Broberger C, Xu ZQ, Sergeyev V, Ubink R, Diez M. Neuropeptides: an overview. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1337–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fricker LD. Neuropeptides and Other Bioactive Peptides: from Discovery to Function. San Rafael: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hökfelt T, Bartfai T, Bloom F. Neuropeptides: opportunities for drug discovery. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:463–472. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Wied D. Long term effect of vasopressin on the maintenance of a conditioned avoidance response in rats. Nature. 1971;232:58–60. doi: 10.1038/232058a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le TT, Lehnert S, Colgrave ML. Neuropeptidomics applied to studies of mammalian reproduction. Peptidomics. 2013;1:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fricker LD, Lim J, Pan H, Che FY. Peptidomics: identification and quantification of endogenous peptides in neuroendocrine tissues. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25:327–344. doi: 10.1002/mas.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prigge ST, Mains RE, Eipper BA, Amzel LM. New insights into copper monooxygenases and peptide amidation: structure, mechanism and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:1236–1259. doi: 10.1007/PL00000763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huttner WB. Tyrosine sulfation and the secretory pathway. Annu Rev Physiol. 1988;50:363–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.002051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veo K, Reinick C, Liang L, Moser E, Angleson JK, Dores RM. Observations on the ligand selectivity of the melanocortin 2 receptor. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2011;172:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eipper BA, Mains RE. Structure and biosynthesis of pro-adrenocorticotropin/endorphin and related peptides. Endocr Rev. 1980;1:1–27. doi: 10.1210/edrv-1-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eipper BA, Mains RE, Herbert E. Peptides in the nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1986;9:463–468. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–660. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes A, Heilig M, Rupniak NM, Steckler T, Griebel G. Neuropeptide systems as novel therapeutic targets for depression and anxiety disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Pol AN. Neuropeptide transmission in brain circuits. Neuron. 2012;76:98–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swaab DF, Bao AM, Lucassen PJ. The stress system in the human brain in depression and neurodegeneration. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:141–194. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clynen E, Swijsen A, Raijmakers M, Hoogland G, Rigo JM. Neuropeptides as targets for the development of anticonvulsant drugs. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;50:626–646. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8669-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner FM. Classical neurotransmitters and neuropeptides involved in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(Suppl 2):S97. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barson JR, Leibowitz SF. Hypothalamic neuropeptide signaling in alcohol addiction. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;65:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters EM, Ericson ME, Hosoi J, Seiffert K, Hordinsky MK, Ansel JC, et al. Neuropeptide control mechanisms in cutaneous biology: physiological and clinical significance. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1937–1947. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatemoto K. Neuropeptide Y: complete amino acid sequence of the brain peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:5485–5489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.18.5485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovejoy DA, Fischer WH, Ngamvongchon S, Craig AG, Nahorniak CS, Peter RE, et al. Distinct sequence of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in dogfish brain provides insight into GnRH evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:6373–6377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hummon AB, Amare A, Sweedler JV. Discovering new invertebrate neuropeptides using mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25:77–98. doi: 10.1002/mas.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stenfors C, Mathé AA, Theodorsson E. Chromatographic and immunochemical characterization of rat brain neuropeptide Y-like immunoreactivity (NPY-LI) following repeated electroconvulsive stimuli. J Neurosci Res. 1995;41:206–212. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490410208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theodorsson A, Theodorsson E. Estradiol increases brain lesions in the cortex and lateral striatum after transient occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in rats: no effect of ischemia on galanin in the stroke area but decreased levels in the hippocampus. Peptides. 2005;26:2257–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hummon AB, Richmond TA, Verleyen P, Baggerman G, Huybrechts J, Ewing MA, et al. From the genome to the proteome: uncovering peptides in the Apis brain. Science. 2006;314:647–649. doi: 10.1126/science.1124128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Kelley WP, Billimoria CP, Christie AE, Pulver SR, Sweedler JV, et al. Mass spectrometric investigation of the neuropeptide complement and release in the pericardial organs of the crab, Cancer borealis. J Neurochem. 2003;87:642–656. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romanova EV, Roth MJ, Rubakhin SS, Jakubowski JA, Kelley WP, Kirk MD, et al. Identification and characterization of homologues of vertebrate beta-thymosin in the marine mollusk Aplysia californica. J Mass Spectrom. 2006;41:1030–1040. doi: 10.1002/jms.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Predel R, Wegener C, Russell WK, Tichy SE, Russell DH, Nachman RJ. Peptidomics of CNS-associated neurohemal systems of adult Drosophila melanogaster: a mass spectrometric survey of peptides from individual flies. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:379–392. doi: 10.1002/cne.20145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturm RM, Dowell JA, Li L. Rat brain neuropeptidomics: tissue collection, protease inhibition, neuropeptide extraction, and mass spectrometric analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;615:217–226. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-535-4_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Sweedler JV. Peptides in the brain: mass spectrometry-based measurement approaches and challenges. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2008;1:451–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.113053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Che FY, Zhang X, Berezniuk I, Callaway M, Lim J, Fricker LD. Optimization of neuropeptide extraction from the mouse hypothalamus. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:4667–4676. doi: 10.1021/pr060690r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Svensson M, Sköld K, Svenningsson P, Andren PE. Peptidomics-based discovery of novel neuropeptides. J Proteome Res. 2003;2:213–219. doi: 10.1021/pr020010u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schrader M, Schulz-Knappe P, Fricker LD. Historical perspective of peptidomics. EuPA Open Proteom. 2014;3:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Che FY, Lim J, Pan H, Biswas R, Fricker LD. Quantitative neuropeptidomics of microwave-irradiated mouse brain and pituitary. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1391–1405. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500010-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theodorsson E, Stenfors C, Mathé AA. Microwave irradiation increases recovery of neuropeptides from brain tissues. Peptides. 1990;11:1191–1197. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(90)90151-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dowell JA, Heyden WV, Li L. Rat neuropeptidomics by LC-MS/MS and MALDI-FTMS: Enhanced dissection and extraction techniques coupled with 2D RP-RP HPLC. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:3368–3375. doi: 10.1021/pr0603452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JE, Atkins N, Jr, Hatcher NG, Zamdborg L, Gillette MU, Sweedler JV, et al. Endogenous peptide discovery of the rat circadian clock: a focused study of the suprachiasmatic nucleus by ultrahigh performance tandem mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:285–297. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900362-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nylander I, Stenfors C, Tan-No K, Mathé AA, Terenius L. A comparison between microwave irradiation and decapitation: basal levels of dynorphin and enkephalin and the effect of chronic morphine treatment on dynorphin peptides. Neuropeptides. 1997;31:357–365. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(97)90072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bora A, Annangudi SP, Millet LJ, Rubakhin SS, Forbes AJ, Kelleher NL, et al. Neuropeptidomics of the supraoptic rat nucleus. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:4992–5003. doi: 10.1021/pr800394e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen R, Jiang X, Conaway MC, Mohtashemi I, Hui L, Viner R, et al. Mass spectral analysis of neuropeptide expression and distribution in the nervous system of the lobster Homarus americanus. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:818–832. doi: 10.1021/pr900736t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia C, Lietz CB, Ye H, Hui L, Yu Q, Yoo S, et al. A multi-scale strategy for discovery of novel endogenous neuropeptides in the crustacean nervous system. J Proteomics. 2013;91:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sasaki K, Osaki T, Minamino N. Large-scale identification of endogenous secretory peptides using electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:700–709. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.017400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayakawa E, Menschaert G, De Bock PJ, Luyten W, Gevaert K, Baggerman G, et al. Improving the identification rate of endogenous peptides using electron transfer dissociation and collision-induced dissociation. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:5410–5421. doi: 10.1021/pr400446z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Craig R, Beavis RC. TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1466–1467. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma B, Zhang K, Hendrie C, Liang C, Li M, Doherty-Kirby A, et al. PEAKS: powerful software for peptide de novo sequencing by tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:2337–2342. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fälth M, Sköld K, Norrman M, Svensson M, Fenyö D, Andren PE. SwePep, a database designed for endogenous peptides and mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:998–1005. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500401-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Southey BR, Amare A, Zimmerman TA, Rodriguez-Zas SL, Sweedler JV. NeuroPred: a tool to predict cleavage sites in neuropeptide precursors and provide the masses of the resulting peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W267–W272. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romanova EV, Sweedler JV. Peptidomics for the discovery and characterization of neuropeptides and hormones. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romanova EV, Dowd SE, Sweedler JV. Quantitation of endogenous peptides using mass spectrometry based methods. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hou X, Xie F, Sweedler JV. Relative quantitation of neuropeptides over a thousand-fold concentration range. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:2083–2093. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Che FY, Vathy I, Fricker LD. Quantitative peptidomics in mice: effect of cocaine treatment. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;28:265–275. doi: 10.1385/JMN:28:3:265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Che FY, Yuan Q, Kalinina E, Fricker LD. Peptidomics of Cpe fat/fat mouse hypothalamus: effect of food deprivation and exercise on peptide levels. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4451–4461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Décaillot FM, Che FY, Fricker LD, Devi LA. Peptidomics of Cpefat/fat mouse hypothalamus and striatum: effect of chronic morphine administration. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;28:277–284. doi: 10.1385/JMN:28:3:277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wardman JH, Zhang X, Gagnon S, Castro LM, Zhu X, Steiner DF, et al. Analysis of peptides in prohormone convertase 1/3 null mouse brain using quantitative peptidomics. J Neurochem. 2010;114:215–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang X, Pan H, Peng B, Steiner DF, Pintar JE, Fricker LD. Neuropeptidomic analysis establishes a major role for prohormone convertase-2 in neuropeptide biosynthesis. J Neurochem. 2010;112:1168–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee JE, Zamdborg L, Southey BR, Atkins N, Jr, Mitchell JW, Li M, et al. Quantitative peptidomics for discovery of circadian-related peptides from the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:585–593. doi: 10.1021/pr300605p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Southey BR, Lee JE, Zamdborg L, Atkins N, Jr, Mitchell JW, Li M, et al. Comparing label-free quantitative peptidomics approaches to characterize diurnal variation of peptides in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Anal Chem. 2014;86:443–452. doi: 10.1021/ac4023378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scholz B, Alm H, Mattsson A, Nilsson A, Kultima K, Savitski MM, et al. Neuropeptidomic analysis of the embryonic Japanese quail diencephalon. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rossbach U, Nilsson A, Fälth M, Kultima K, Zhou Q, Hallberg M, et al. A quantitative peptidomic analysis of peptides related to the endogenous opioid and tachykinin systems in nucleus accumbens of rats following naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1091–1098. doi: 10.1021/pr800669g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Romanova EV, Lee JE, Kelleher NL, Sweedler JV, Gulley JM. Comparative peptidomics analysis of neural adaptations in rats repeatedly exposed to amphetamine. J Neurochem. 2012;123:276–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Romanova EV, Lee JE, Kelleher NL, Sweedler JV, Gulley JM. Mass spectrometry screening reveals peptides modulated differentially in the medial prefrontal cortex of rats with disparate initial sensitivity to cocaine. AAPS J. 2010;12:443–454. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9204-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]