Abstract

Intramuscular pressure (IMP), a correlate of muscle tension, may fill an important clinical testing void. A barrier to implementing this measure clinically is its non-uniform distribution, which is not fully understood. Pressure is generated by changes in fluid mass and volume, therefore 3D volumetric strain distribution may affect IMP distribution. The purpose of this study was to develop a method for quantifying 3D volumetric strain distribution in the human tibialis anterior (TA) during passive tension using cine Phase Contrast (CPC) MRI and to assess its accuracy and precision.

Five healthy subjects each participated in three data collections. A custom MRI-compatible apparatus repeatedly rotated the subjects’ ankle between 0 and 26 degrees plantarflexion while CPC MRI data were collected. Additionally, T2-weighted images of the lower leg were collected both before and after the CPC data collection with the ankle stationary at both 0 and 26 degrees plantarflexion for TA muscle segmentation. A 3D hexahedral mesh was generated based on the TA surface before CPC data collection with the ankle at 0 degrees plantarflexion and the node trajectories were tracked using the CPC data. The volumetric strain of each element was quantified.

Three tests were employed to assess the measure accuracy and precision. First, to quantify leg position drift, the TA segmentations were compared before and after CPC data collection. This error was 1.5±0.7 mm. Second, to assess the surface node trajectory accuracy, the deformed mesh surface was compared to the TA segmented at 26 degrees of ankle plantarflexion. This error was 0.6±0.2 mm. Third, the standard deviation of volumetric strain across the three data collections was calculated for each element and subject. The median between-day variability across subjects and mesh elements was 0.06 mm3/mm3 (95% confidence interval 0.01 to 0.18 mm3/mm3). Overall the results demonstrated excellent accuracy and precision.

Keywords: Cine phase contrast, volumetric strain, intramuscular pressure, skeletal muscle, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Musculoskeletal health is an important factor in quality of life. Regular exercise is negatively associated with a number of health risk factors, such as heart disease, obesity, chronic disease, and cardiac death [1–5]. Conversely, skeletal muscle weakness and disease are associated with increased occurrence of falls, reduced independence, reduced mobility, reduced physical activity, and associated psychological and physical health decrements [6–9]. These factors motivate research efforts aimed at improving measures of muscle health and strength.

Intramuscular pressure (IMP) has been identified as a promising means of quantifying tension generated in individual muscles [10–14] and has the potential to fill an important void in clinical testing. Unlike current clinical methods, IMP may be used to quantify the mechanical force generated by an individual muscle during either maximal voluntary contraction [15] or functional dynamic tasks [16]. Additionally, IMP is sensitive to both active and passive tension [17, 18]. Adding IMP measurement to clinical assessment of pathological gait may aid in treatment and intervention specificity.

The relationship between muscle tension and IMP is complex. IMP is non-uniformly distributed in skeletal muscle, increasing with muscle depth and near stiff structures such as tendon and bone [11, 12]. This distribution is hypothesized to be a function of muscle geometry, size, architecture, and boundary conditions [12, 14]. Therefore, the most promising way to establish IMP as a clinical tool for individual muscle force estimation is to develop a muscle-specific computational model [19]. This may be most efficiently accomplished by recognizing the parallels between IMP and strain distribution in skeletal muscle [20–25]. Like IMP, strain is a function of both activation and passive tension, increases with muscle depth, and is highest near the aponeurosis [26], suggesting that a direct relationship may exist. Such a relationship may be expected, because muscle strain, the deformation of the tissue that confines the intramuscular fluid, is mechanically coupled to IMP. Recent scientific progress has been made in modelling the relationship between tension and strain in skeletal muscle [26]. Defining a clear relationship between strain and IMP, therefore, could bridge the gap between tension and IMP and bring this application significantly closer to clinical implementation.

Cine Phase Contrast (CPC) is a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) technique that can be used to quantify skeletal muscle strain [21–25]. Initially developed for cardiac muscle application [27], this sequence acquires a temporal sampling of spatial velocity maps in muscle over a motion cycle. To calculate strain, a mesh is first created within the muscle region of interest, establishing the initial condition of nodes and elements distributed throughout the muscle. Each mesh node displacement trajectory is tracked by integrating its velocity curve over the motion cycle, which is defined by the CPC data. Applying the node displacements to the mesh generates a deformed mesh that represents the muscle deformation. The strain can then be quantified in each element throughout the mesh, providing a measure of muscle strain distribution.

To date skeletal muscle strain distribution analyses have been limited to a 2D plane [20–25]. Although these measures have demonstrated potential correlation with IMP [26], it is expected that 3D volumetric (or dilatational) strain may be a better correlate of interstitial fluid pressure because pressure is generated by changes in fluid mass to volume ratio. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop a method for quantifying 3D volumetric strain distribution in human skeletal muscle using CPC MRI and to assess the accuracy and precision of the method. For method development purposes, we chose to quantify the volumetric strain of the tibialis anterior (TA) during passive tension. This selection was strategic for a couple of reasons. CPC MRI requires uniform cyclic motion for an extended time period (particularly for a 3D measure) and passive tension, which is more easily controlled, is a logical first step in method development. Additionally, the TA is isolated in action (plantarflexion-inversion) and superficial in location, which are ideal characteristics for future IMP studies in the same muscle.

Methods

Subjects

Five subjects (4 F, 25±1 y.o., 22.0±2.0 BMI) with good neuromuscular health consented to participate in this study. The subjects each participated in three identical data collections, scheduled within a one week timeframe to minimize physiological muscle changes. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB #13-002825).

Data collection

Subjects were positioned on a custom MRI-compatible apparatus designed to continuously and passively rotate the right ankle (Figure 1). Twenty-six degrees was found to be the largest end range of plantarflexion motion that a test subject was able to comfortably tolerate for greater than 5 minutes, which is on the order of peak plantarflexion during normal human gait. An approximately 2 second motion cycle was determined to be optimum for a number of relevant factors: for comparability to human stride rate (~1s on average); to allow a high enough CPC sampling rate to reproduce the motion curve (~0.17s temporal resolution using 4 views per second); and to fall well below the speed-torque capabilities of the motor. Therefore the ankle was rotated between 0 (neutral) and 26 degrees of plantarflexion at 30 deg/sec for the ~1200 cycles required for the data collection. The subject’s ankle axis of rotation was carefully aligned with the apparatus axis of rotation so that it could be rotated through the full range of motion with minimal extraneous leg movement. The subject was also positioned as similarly as possible between data collections and the MRI landmark position (which defines the global origin) was marked on the subject’s leg using a surgical marker to ensure consistency between visits. A custom rectangular receive-only two-channel coil was placed over the lower leg such that it covered the length of the TA and remained undisturbed by the ankle motion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Custom MRI-compatible apparatus used to passively rotate the subject’s ankle while minimizing extraneous limb movement. (a) A lead screw was used to convert the motor rotation into linear translation of an 8 ft fiberglass rod which, in turn, controlled rotation of the foot plate. (b) The subject was positioned with slight knee flexion and was supported by foam pads. Straps were used to secure the upper legs and the foot and the coil was placed over the lower right leg. (c) The only component of the apparatus with ferromagnetic parts was the motor, which was positioned at the end of the patient table farthest from the magnet bore. Radiofrequency emissions were contained using a Faraday cage around the motor and a copper mesh sleeve over the extension cable.

MRI data were collected using a commercially available Fast 2D Phase Contrast sequence (Error! Reference source not found.) on a 1.5T scanner (Signa HDX 16.0, GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI). A 0.5 Hz square wave was used to trigger both the custom sawtooth-shaped ankle motion profile and the CPC sequence (via a cardiac simulator). Eight adjacent sagittal image slices were acquired (Error! Reference source not found.) to cover the width of the tibialis anterior (TA). Velocity was encoded in the frequency (S-I), phase (A-P), and through-plane (M-L) directions in turn. The minimum encoding velocity of 50 mm/s was selected; where encoding velocity is the maximum velocity that can be measured before aliasing occurs. It was expected that 50 mm/s would suffice because the maximum TA tendon displacement was expected to be less than 5 cm over the 1 second half cycle. After the data collection it was confirmed that the maximum measured velocity within the region of interest was 34 mm/s.

Additionally, three sets of axial T2-weighted image stacks were collected: two prior to CPC imaging (one at the neutral and one at the 26 degrees plantarflexed ankle position) and one after CPC imaging (at the neutral ankle position). Slices were arranged to cover the length of the TA (5 mm thick, 20 cm FOV, 320×320 in-plane resolution, 41.1 ms TE). Slice spacing was 0 mm prior to CPC imaging and 3 mm after.

Data processing

The TA was manually segmented from each of the axial T2-weighted images (Mimics, Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). An “exact” muscle segmentation was used to compare the TA position before and after CPC data collection (Figure 2). An additional “eroded” segmentation (eroded by 1.5 to 2.5 mm relative to the “exact” segmentation at the muscle boundaries) was created for strain tracking in order to mitigate the edge blurring effects of partial volume and minor (< 1.5 mm) leg drift (Figure 2). Using the anatomical structures visible on the images as a reference, care was taken to ensure that the segmentations were visually consistent between all data collections for each subject. Each segmentation was wrapped, smoothed and exported as a surface mesh (STL) file.

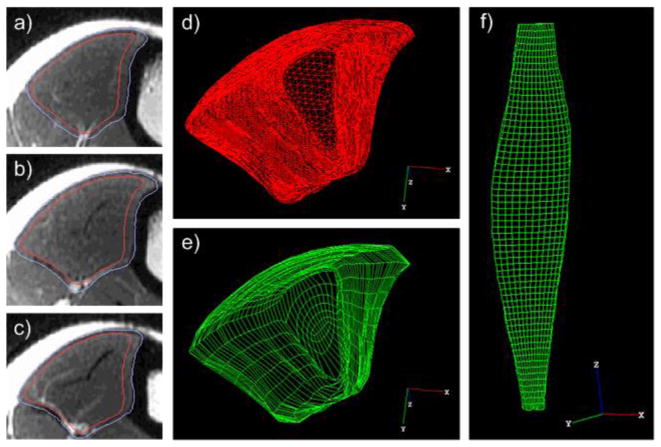

Figure 2.

a–c) Three axial T2-weighted images from one subject along the length of the TA showing the “exact” muscle segmentation (outer line) and “eroded” segmentation (inner line). The segmentation was eroded by ~2.5mm near the cortical bone and ~1.5mm around the rest of the border. d–e) Distal view of the segmented TA and the corresponding 3D hexahedral mesh. f) Frontal view of the 3D hexahedral mesh representation of the TA.

The initial position of the TA was defined by the T2-weighted images collected before CPC imaging with the ankle at neutral position. The “eroded” surface mesh segmented from these images was used to define the 3D mesh boundary. A 3D hexahedral mesh with 11808 elements ranging in size from 0.5 to 22.8 mm3 (mean of 6.4 mm3) was manually generated (TrueGrid, XYZ Scientific, Livermore, CA) for each data collection, ensuring consistent element location relative to the muscle across data collections and subjects (Figure 2). The hex mesh was then output for use in Abaqus (Dassault Systemes Simulia Corp., Providence, RI).

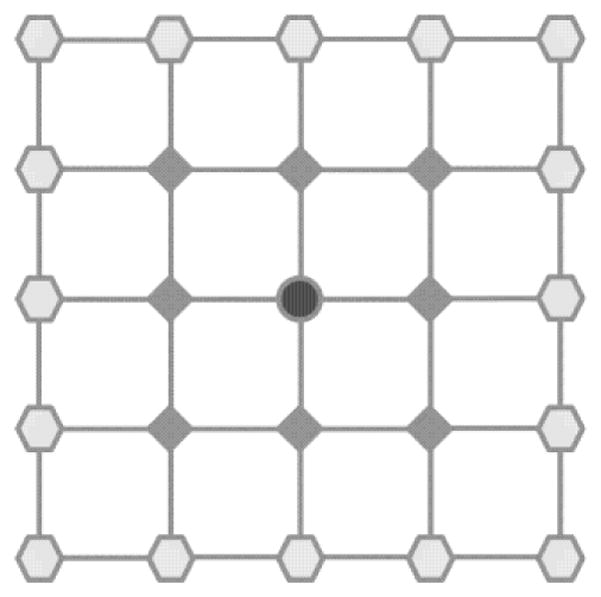

Before beginning post-processing, the CPC-generated velocity maps were smoothed and corrected according to Jensen et al [28]. Next the 3D trajectory of each mesh node was independently tracked according to the forward-backward integration method [29, 30] using custom software (Matlab, The Mathworks, Natick, MA). Velocities were linearly interpolated between pixel centers for finer scale tracking. After completing the mesh node tracking, node trajectories were smoothed using a nearest neighbors technique (Figure 3). The output was a single 3D vector of each node, pointing from its initial position (neutral ankle) to its final position (plantarflexed ankle). The mesh file from TrueGrid was then imported into Abaqus and the 3D node trajectories were applied as boundary conditions to the model in order to obtain the final deformed mesh representing the lengthened TA. Volumetric strain was calculated for each element using a convex hull algorithm and custom code (Abaqus Python; Python v2.7). The surface of the final deformed mesh was exported from Abaqus as a VRML file and then converted to an STL file for comparative analysis [31].

Figure 3.

Validation testing

Leg position drift during CPC MRI data collection can cause unresolvable artifacts because the basic assumptions of cyclic motion repeatability are violated [32]. Therefore, the purpose of the first validation test was to determine whether any drift occurred in the base position of the TA (as defined by the anatomical MRI images taken with the ankle in the neutral position) over the course of the data collection. The RMS error between the “exact” TA segmentation surfaces before and after CPC imaging was calculated using the Hausdorff distance measure (MeshLab v1.3.3, 3D CoForm project) to quantify this drift.

The purpose of the second validation test was to determine the positional accuracy of the final deformed mesh. Although the trajectories of the internal mesh nodes cannot be directly validated, the anatomical images of the TA with the ankle in the plantarflexed position provide information about the expected trajectories of the superficial mesh nodes. The RMS error was calculated between the deformed mesh surface and the segmented TA surface (gold standard), again using the Hausdorff distance measure.

The purpose of the final validation test was to quantify the precision of the volumetric strain output. This was accomplished by measuring the standard deviation of the volumetric strain across the three data collections for each element and subject. This provided a measure of between-day variability.

Results

The RMS error between the neutral TA positions at the beginning and the end of the data collection, averaged across subjects and trials, was 1.5±0.7 mm (Figure 4). The subject- and trial-averaged RMS error between the deformed mesh and the true strained TA (defined by the T2-weighted MRI images) was 0.6±0.2 mm (Figure 4). In contrast, the subject- and trial-averaged RMS error between the deformed mesh and the original unstrained TA surface was 1.2±0.5 mm, which is 0.6±0.4 mm greater (Figure 4). One trial was excluded from the RMS error summary because it failed Grubb’s test for outliers (4.0 mm RMS error between neutral TA positions and 5.5 mm RMS error between deformed mesh and true strained TA).

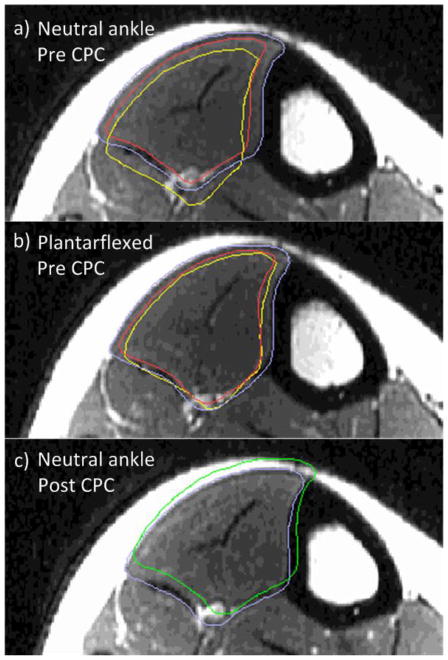

Figure 4.

Example T2-weighted axial image of one subject’s TA with the ankle in neutral position (a) and plantarflexed position (b) before CPC imaging, and neutral position after CPC imaging (c). Outlined in periwinkle is the “exact” and in red is the “eroded” segmentation of the current image. In yellow (a,b) is the cross-section of the deformed mesh, which aligns with the “eroded” segmentation of the TA with the ankle in the plantarflexed position (b), as expected. In green (c) is the neutral ankle position “exact” TA segmentation from before CPC imaging (shown as periwinkle in a), which is being compared to the “exact” segmentation (in periwinkle) after CPC imaging.

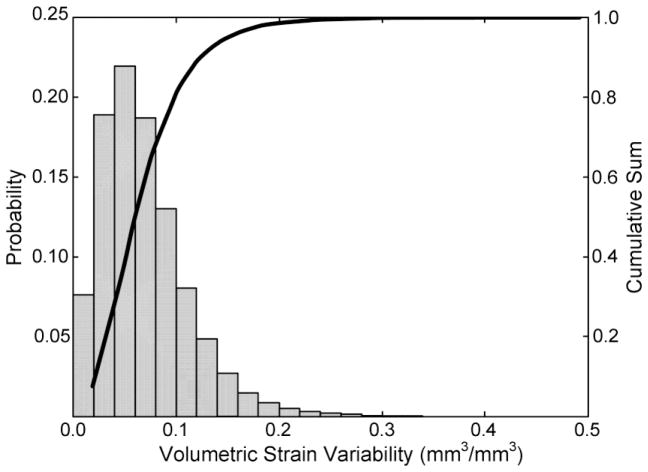

The median between-day volumetric strain variability across all subjects and mesh elements was 0.06 mm3/mm3 (95% confidence interval 0.01 to 0.18 mm3/mm3), with 80 percent of the data falling below 0.1 mm3/mm3 (Figure 5). The subject whose trial was excluded from the RMS error summary was included in the variability analysis because her variability data was on par with the remainder of the subjects (median of 0.06 mm3/mm3; 95% confidence interval 0.01 to 0.19 mm3/mm3). As a comparison, the 95% confidence interval of the volumetric strain across subjects, trials, and mesh elements was −0.09 to 0.22 mm3/mm3.

Figure 5.

Volumetric strain variability distribution for all subjects and mesh elements. Eighty percent of the variability is less than 0.1mm3/mm3.

Discussion

This study demonstrated a novel method of quantifying 3D strain in human skeletal muscle. Anatomical MRI images provided a means of quantifying the accuracy of the deformed mesh boundary and repeated data collections provided a means of quantifying between-day precision. Overall, the demonstrated results suggest validity of the final deformed mesh.

A mean RMS error of 1.5 mm between the TA position before versus after CPC imaging, which is just over the in-plane spatial resolution (1.25 mm), provides evidence for an ideal data collection with minimal drift of the resting leg position and repeatable cyclic motion. This is important for avoiding artifacts due to non-identical repetitions [32]. The strong agreement between the strained mesh and the outline of the TA when the ankle was plantarflexed (0.6±0.2 mm RMS error) indicates good accuracy of the results by demonstrating that the trajectories of the most superficial nodes behaved as expected. In fact, these RMS error values are likely an overestimate of the true error, given that they also encompass human segmentation error. The fact that the Hausdorff distance measure was smaller between the strained mesh and the TA outline when the ankle was planterflexed versus neutral (decrease of 0.6±0.4 mm) indicates that there was enough change in the stretched TA morphology to substantiate this analysis. It can be inferred from the superficial node accuracy that the motion of the internal nodes was also appropriate in both magnitude and direction.

The volumetric strain repeatability measurements are also promising. The targeted application of this method is to provide a way to identify regional differences in volumetric strain in an individual muscle. However, the volumetric strain variability that we were able to obtain was a measure of between-day variability. It must be noted that the 95% confidence interval of the between-day variability is only about 50% lower than the 95% confidence interval of volumetric strain (0.01 to 0.18 versus −0.09 to 0.22 mm3/mm3), but this variability encompasses a number of factors that are not encountered within a single data collection. For example, the between-day variability includes setup variability, minor physiological variability in the subject between days, as well as variability in the manual components of data processing (segmentation and meshing). Therefore it is likely that the within-day variability is sufficiently lower than the measured volumetric strain range to at least allow differentiation between regions of high and low strains.

One of the novel components of the methods described in this study, which has not been discussed in detail previously, is the use of mesh boundary erosion. Two factors that come into play with CPC post-processing are partial volume effects, particularly near cortical bone where the signal is effectively zero, and the small but unavoidable drift in leg position (< 1.5 mm). CPC-related partial volume effects have been discussed previously in relation to laminar flow measurement [33]. In this application, partial volume effects near the bone can cause mesh node tracking errors because of noisy data. The importance of motion repeatability has also been established [32]. Leg position drift can cause tracking errors due to misalignment between the mesh and the relevant anatomy, particularly at boundaries between organs (i.e. the TA and skin or the TA and another muscle). To mitigate these factors, we chose to use an “eroded” segmentation for strain tracking. As muscle boundaries are not targeted for IMP measurements, no important data was lost with this method.

Although the application of this method is ultimately intended for muscle activation, this study was focused on passive tension of the TA. The primary reason for this was the long duration of CPC imaging needed for 3D analyses. Forty minutes is a challenging duration to maintain repeatable muscle activation. In contrast, it is much easier to ensure motion repeatability with motor-controlled passive muscle tension. Focusing this study on passive muscle tension, therefore, allowed for data collection and processing method development and validation without additional motion inconsistency-related variability. Furthermore, the IMP-force and strain-force relationships hold for both active and passive muscle activation [10], therefore the volumetric strain distribution analysis is valuable under passive tension conditions as well.

There are a few limitations and future applications that should be noted in the current study. The range of element sizes in the muscle mesh was rather large (0.5 to 22.8 mm3) due to the tapering shape of the muscle as well as mesh element continuity requirements. This may create regional differences in volumetric strain variability [28]. The accuracy analysis was limited due to the lack of a gold standard on internal muscle dynamics. Additionally, the variability measure was limited to between-day, as previously mentioned, due to the long duration of the data collection.

A future application for this model is to introduce muscle fiber directions using element orientations [20], which would enable analysis of other modes of 3D strain such as along fiber principle and shear strains. The current method focuses on two time points (ankle at neutral and 26 degrees plantarflexion), but the data allow time-resolved analysis of the entire motion, which may be useful for some applications. The demonstrated method also provides a basis for quantifying 3D volumetric strain during active muscle contraction. This could be accomplished either by limiting voluntary activation to low levels and incorporating resting periods or by applying faster CPC sequences for 3D application to reduce the total data collection time [34].

Intramuscular pressure – a demonstrated correlate of muscle force – carries strong potential for clinical application. Yet the ability to quantify muscle force from isolated IMP measurements evades us. Previous studies have attempted to model the relationship between these measures [19], but we still lack a model that aptly characterizes the relationship in vivo. In contrast, the relationship between muscle force and strain distribution has been successfully modelled [26]. This same study points to parallel trends between strain and intramuscular pressure distribution, indicating that a relationship may exist [11, 12, 26]. Identifying such a relationship would substantially advance our ability to model IMP in vivo both because strain distribution can be mapped more thoroughly than IMP and because of previously demonstrated modelling success. Given that pressure is generated by changes in fluid mass to volume ratio, volumetric strain is a more likely correlate of intramuscular pressure than 2D principal or shear strain. This study is the first step toward addressing this hypothesis, as it is the first to demonstrate a method for quantifying volumetric strain in skeletal muscle and has demonstrated good accuracy and repeatability of the measure. With this new ability to characterize volumetric strain distribution, we expect that our understanding of the mechanism behind non-uniform IMP distribution will be advanced as well as our ability to model it.

Table 1.

Cine Phase Contrast MRI imaging parameters.

| Pulse sequence | Vasc PC |

|---|---|

| Imaging options | Gat, Seq, Fast |

| Mode | 2D |

| Orientation | Feet-First Supine |

| Imaging plane | Sagittal |

| Frequency direction | S/I |

| Gradient | Whole |

| X/Y matrix | 192 × 192 |

| Phase FOV | 240 mm |

| X/Y resolution | 1.25 × 1.25 mm |

| Slice thickness | 5.0 mm |

| # Slices | 8 |

| Encoding velocity (venc) | 50 mm/s |

| Views per segment | 4 |

| # Time segments | 12 |

| Data collection duration | 40 min (1:40 per slice and encoding direction) |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant (R01 HD31476) and a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant (T32 AR56950), as well as by the Mayo Graduate School. The authors would like to give a special thanks to John Novotny for technical contributions.

References

- 1.Morris JN, et al. Vigorous exercise in leisure-time: protection against coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1980;2(8206):1207–10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manson JE, et al. A prospective study of walking as compared with vigorous exercise in the prevention of coronary heart disease in women. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;341(9):650–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jolliffe JA, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2000;(4):CD001800. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouchard C, Depres JP, Tremblay A. Exercise and obesity. Obesity research. 1993;1(2):133–47. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in chronic disease. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2006;16(Suppl 1):3–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLean RR, et al. Criteria for clinically relevant weakness and low lean mass and their longitudinal association with incident mobility impairment and mortality: the foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) sarcopenia project. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2014;69(5):576–83. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busse ME, Wiles CM, van Deursen RW. Community walking activity in neurological disorders with leg weakness. Journal of neurology neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2006;77(3):359–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.074294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Ross R. Low relative skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) in older persons is associated with functional impairment and physical disability. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50(5):889–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfson L, et al. Strength is a major factor in balance, gait, and the occurrence of falls. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 1995;50(Spec No):64–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.special_issue.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winters TM, et al. Correlation between isometric force and intramuscular pressure in rabbit tibialis anterior muscle with an intact anterior compartment. Muscle & nerve. 2009;40(1):79–85. doi: 10.1002/mus.21298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aratow M, et al. Intramuscular pressure and electromyography as indexes of force during isokinetic exercise. Journal of applied physiology. 1993;74(6):2634–40. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.6.2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sejersted OM, et al. Intramuscular fluid pressure during isometric contraction of human skeletal muscle. Journal of applied physiology: respiratory environmental and exercise physiology. 1984;56(2):287–95. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis J, Kaufman KR, Lieber RL. Correlation between active and passive isometric force and intramuscular pressure in the isolated rabbit tibialis anterior muscle. Journal of biomechanics. 2003;36(4):505–12. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadamoto T, Bonde-Petersen F, Suzuki Y. Skeletal muscle tension, flow, pressure, and EMG during sustained isometric contractions in humans. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology. 1983;51(3):395–408. doi: 10.1007/BF00429076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sejersted OM, Hargens AR. Intramuscular pressures for monitoring different tasks and muscle conditions. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1995;384:339–50. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1016-5_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballard RE, et al. Leg intramuscular pressures during locomotion in humans. Journal of applied physiology. 1998;84(6):1976–81. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.6.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumann JU, Sutherland DH, Hanggi A. Intramuscular pressure during walking: an experimental study using the wick catheter technique. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1979;(145):292–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufman KRS, DH Dynamic intramuscular pressure measurement during gait. Operative techniques in sports medicine. 1995;3(4):250–255. doi: 10.1016/s1060-1872(95)80022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkyn TR, et al. Finite element model of intramuscular pressure during isometric contraction of skeletal muscle. Physics in medicine and biology. 2002;47(22):4043–61. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/22/309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blemker SS, Delp SL. Three-dimensional representation of complex muscle architectures and geometries. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2005;33(5):661–73. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-1433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pappas GP, et al. Nonuniform shortening in the biceps brachii during elbow flexion. Journal of applied physiology. 2002;92(6):2381–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00843.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong X, et al. Imaging two-dimensional displacements and strains in skeletal muscle during joint motion by cine DENSE MR. Journal of biomechanics. 2008;41(3):532–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silder A, Reeder SB, Thelen DG. The influence of prior hamstring injury on lengthening muscle tissue mechanics. Journal of biomechanics. 2010;43(12):2254–2260. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinugasa R, et al. Phase-contrast MRI reveals mechanical behavior of superficial and deep aponeuroses in human medial gastrocnemius during isometric contraction. Journal of applied physiology. 2008;105(4):1312–20. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90440.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finni T, et al. Nonuniform strain of human soleus aponeurosis-tendon complex during submaximal voluntary contractions in vivo. Journal of applied physiology. 2003;95(2):829–37. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00775.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blemker SS, Pinsky PM, Delp SL. A 3D model of muscle reveals the causes of nonuniform strains in the biceps brachii. Journal of biomechanics. 2005;38(4):657–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelc NJ, Glover GH. G.E. Company, editor. Method for fast scan cine NMR imaging. United States: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen ER, et al. Error analysis of cine phase contrast MRI velocity measurements used for strain calculation. Journal of biomechanics. 2015;48(1):95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelc NJ, et al. Tracking of cyclic motion with phase-contrast cine MR velocity data. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 1995;5(3):339–45. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880050319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou H, Novotny JE. Cine phase contrast MRI to measure continuum Lagrangian finite strain fields in contracting skeletal muscle. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2007;25(1):175–84. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Min P, editor. MeshConv: 3D model converter. Available from: http://www.cs.princeton.edu/~min/meshconv/

- 32.Sinha S, et al. Computer-controlled, MR-compatible foot-pedal device to study dynamics of the muscle tendon complex under isometric, concentric, and eccentric contractions. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2012;36(2):498–504. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinha S, et al. Muscle kinematics during isometric contraction: development of phase contrast and spin tag techniques to study healthy and atrophied muscles. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2004;20(6):1008–19. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson KM, et al. Improved 3D phase contrast MRI with off-resonance corrected dual echo VIPR. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;60(6):1329–36. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]