Abstract

For cancer prevention, the World Cancer Research Fund & American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) emphasize recommendations to improve individual behavior including avoidance of tobacco products, maintaining a lean body mass, participating in physical activity, consuming a plant based diet, and minimizing the consumption of calorie dense foods, such as sodas, red and processed meats, and alcohol. In this study of 275 healthy premenopausal women, we explored the association of adherence scores with levels of three biomarkers of antioxidant and inflammation status: serum C-reactive protein (CRP), serum γ-tocopherol, and urinary F2-isoprostane. The statistical analysis applied linear regression across categories of adherence to WCRF/AICR recommendations. Overall, 72 women were classified as low (≤4), 150 as moderate (5–6), and 53 as high adherers (≥7). The unadjusted means for CRP were 2.7, 2.0, and 1.7 mg/L for low, moderate, and high adherers (ptrend=0.03); this association was strengthened after adjustment for confounders (ptrend=0.006). The respective values for serum γ-tocopherol were 1.97, 1.63, and 1.45 μg/mL (ptrend=0.02 before and ptrend=0.03 after adjustment). Only for urinary F2-isoprostane, the lower values in high adherers (16.0, 14.5, and 13.3 ng/mL) did not reach statistical significance (ptrend=0.18). In an analysis by body mass index (BMI), overweight and obese women had higher biomarker levels than normal weight women; the trend was significant for CRP (ptrend<0.001) and γ-tocopherol (ptrend=0.003) but not for F2-isoprostane (ptrend=0.14). These findings suggest that both adherence to the WCRF/AICR guidelines and normal BMI status are associated with lower levels of biomarkers that indicate oxidative stress and inflammation.

Keywords: chronic inflammation, cancer prevention, nutrition, lifestyle, recommendations

INTRODUCTION

Nutritional and lifestyle factors are thought to be associated with a higher risk for cancer and other chronic conditions, but little is known whether guidelines from different agencies are related to indicators of lower disease risk. The World Cancer Research Fund & American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) emphasize recommendations to improve individual behavior including avoidance of tobacco products, maintaining a lean body mass, participating in moderate physical activity, consuming a primarily plant based diet, and minimizing the consumption of calorie dense foods and drinks, red and processed meats, and alcohol(1). In two large cohort studies, participants experienced a 9–10% lower mortality for each WCRF/AICR recommendation that was met(2, 3). Based on evidence that chronic inflammation plays a major role in cancer development(4, 5), we evaluated the diet of 275 healthy premenopausal women who completed a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and explored the association of adherence scores with levels of three biomarkers of antioxidant and inflammation status: serum C-reactive protein (CRP), urinary F2-isoprostane, and serum γ-tocopherol. CRP represents a non-specific indicator of inflammation(6) that has been associated with cancer incidence(7) and survival(8). Among markers of oxidative stress, F2-isoprostanes are considered the “gold standard” because they are stable and specific and are only formed directly by chemical oxidation from nitric oxides (NOx) generated in vivo(9–11). Due to their antioxidant activity, tocopherol isomers may shield against oxidative damage(12, 13). In particular, γ-tocopherol selectively protects cells from the DNA-damaging effects of NOx(14–16), possesses anti-inflammatory activity(17), and rises in response to inflammation(18, 19). High circulating levels of γ-tocopherol, i.e., >2.5 μg/mL, do not appear to reflect dietary intake, rather they represent a response to the presence of an inflammatory stimulus. Individuals with circulating levels of γ-tocopherol > 2.5 μg/mL are considered hyper γ-tocopherolemic(20); such elevated levels are associated with low vitamin D status(20, 21), obesity(22), age(23), smoking(20), and CRP(22). Thus, γ-tocopherol may be an excellent overall marker of health risk. We hypothesized that women with high adherence to the WCRF/AICR recommendations have a more favorable inflammatory biomarker profile. In addition, we explored the association between body mass index (BMI) and the same biomarkers of antioxidant and inflammatory status.

METHODS

Study design and population

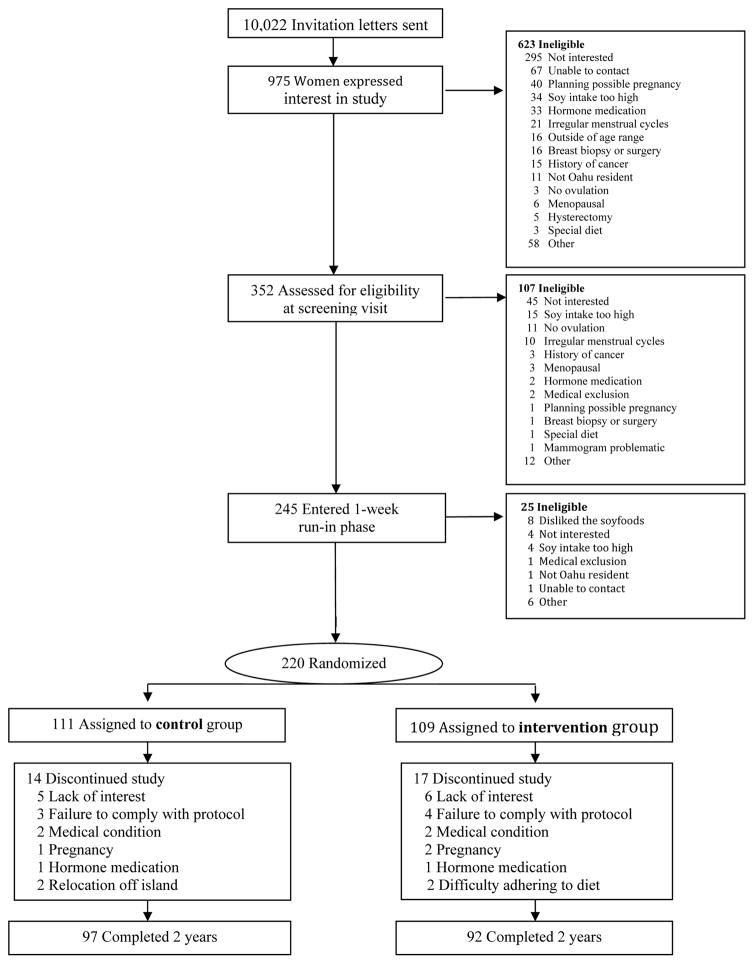

The current analysis used baseline data from two dietary intervention studies (Figure 1): the Breast, Estrogen, and Nutrition (BEAN1), which randomized 220 women to a 2-year clinical trial to examine the effects of 2 daily soy servings on sex steroids and mammographic densities(24), and BEAN2, which was conducted in a cross-over design with 82 women(25). Only data collected at baseline before randomization to an intervention were analyzed. The protocols for both studies were approved by the University of Hawaii Committee on Human Studies and by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating hospitals. All participants signed an informed consent form before entry into the trials. As described in detail previously(24, 25), eligibility criteria for both studies included a normal mammogram, no breast implants, no current oral contraceptive use or pregnancy, no previous cancer diagnosis, intact uterus and ovaries, regular menstrual cycles, and low soy intake. Additional criteria for BEAN2 included the ability to produce at least 10 μL nipple aspirate fluid, one of the study outcomes(25). After exclusion of dropouts and women with incomplete data, the current analysis included 275 women who provided biological samples and complete nutritional information from the baseline FFQ that could be used to score adherence to the WICR/AICR recommendations (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for recruitment and study population of BEAN1 Study (top) and the BEAN2 Study (bottom)

Table 1.

Scoring for WCRF/AICR recommendations based on data from baseline FFQa

| WCRF/AICR recommendation | Associated recommendations used in this study | Met/did not meet recommendation if: | Score | N=275 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body fatness: Be as lean as possible without becoming underweight | Maintain body weight in the normal BMI range | Met: BMI between 18.5 and 25 kg/m2 | 1 | 138 (50.2) |

| Did not meet: BMI <18.5 or ≥25 kg/m2 | 0 | 137 (49.8) | ||

|

| ||||

| Physical activity: Be physically active for at least 30 minutes every day | Be moderately or strenuously physically active at least 3.5 hrs per week | Met: ≥3.5 hrs/week | 1 | 178 (64.7) |

| Did not meet: <3.5 hrs/week | 0 | 97 (35.3) | ||

|

| ||||

| Energy density: Limit consumption of energy dense foods: avoid sugary drinks | Limit the consumption of sugary drinks to less than 250 g per day | Met: <250 g/day | 1 | 196 (71.3) |

| Did not meet: ≥250 g/day | 0 | 79 (28.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Plant foods: Eat more of a variety of vegetables, fruits, whole grains and legumes such as beans | Eat five servings of fruits and vegetables and 1 serving or more of whole grains |

Met: ≥5 servings/day ≥1 serving/day |

1 | 87 (31.6) |

|

Did not meet: ≥5 servings/day <1 serving/day |

0 | 18 (6.5) | ||

| Did not meet: <5 servings/day | 0 | 170 (61.9) | ||

|

| ||||

| Red meat: Limit consumption of red meats (such as beef, pork and lamb) and avoid processed meats | Limit red/processed meat consumption to less than 2.5 servings per day (2.5 servings based on 500 g per week) | Met: <2.5 servings/day | 1 | 243 (88.4) |

| Did not meet: ≥2.5 servings/ day | 0 | 32 (11.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Alcohol: Limit alcoholic drinks | If alcoholic drinks are consumed, limit consumption to no more than one drink per day | Met: ≤1 drink/day | 1 | 248 (90.2) |

| Did not meet: <1 drink/day | 0 | 27 (9.8) | ||

|

| ||||

| Salty foods: Limit consumption of salt; avoid moldy grains or legumes | Limit consumption of salty and processed foods to less than 2400 mg per day | Met: <2400 mg/day | 1 | 132 (48.0) |

| Did not meet: ≥2400 mg/day | 0 | 143 (52.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Smoking: Do not smoke and avoid tobacco smoke | Do not smoke or quit smoking if you are a present smoker | Met: Never | 1 | 179 (65.1) |

| Met: Past | 1 | 17 (6.2) | ||

| Did not meet: current | 0 | 79 (28.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Supplements: Aim to meet nutritional needs through diet alone | Dietary supplements are not recommended for cancer prevention | Not operationalized | N/A | |

WCRF/AICR: World Cancer Research Fund & American Institute for Cancer Research; FFQ: food frequency questionnaire.

Data collection

All participants completed a previously-validated FFQ at baseline that included questions on habitual dietary intake during the last year, physical activity, smoking status, medical history, and reproductive characteristics(26). The FFQ had 8 frequency categories for foods and 9 for beverages. Respondents could choose from three typical serving sizes and photographs were included to help visualize proportions for selected foods. BMI was calculated from baseline weight and height. The FFQs were analyzed utilizing the Food Composition Table maintained by the Nutrition Support Shared Resource at the Cancer Center(27); the databases represent an extensive list of local foods consumed by the various ethnic populations of Hawaii and the Pacific. Food servings were defined according to the Food Guide Pyramid(28).

Sample collection and assays

Serum and urine samples were collected during the midluteal phase using ovulation kits in BEAN1 and confirmation by serum progesterone levels(24) and self-reported menstruation information in BEAN2(25). For this analysis, CRP and serum γ-tocopherol were available for BEAN1 participants only and urinary F2-isoprostane levels for BEAN2 women only. All specimens were stored at −80°C after aliquoting. The CRP assay was based on a latex particle enhanced immunoturbidimetric method using a Cobas MiraPlus clinical autoanalyser and a kit from Pointe Scientific, Inc, Lincoln Park, MI with a detection limit of 0.1 mg/L(29). Serum samples were analyzed for γ-tocopherol by reverse phase high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with photodiode array detection between 220–600 nm(30, 31). The assay was regularly validated during the analysis by inclusion of external standards within each sample batch and through successful participation in the quality assurance program organized by U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (Gaithersburg, MD). Levels of urinary 15-F2t-isoprostane were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Oxford Biomedical Research, Rochester Hills, MI) in 6 batches(32).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, release 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). A scoring system for 8 of the 10 recommendations by the WCRF/AICR for cancer prevention(1) was modeled similar to a previous publication(3). Participants were given a score of 1 or 0 depending on if they met or did not meet a recommendation (Table 1), and the adherence scores were classified as low (<5), moderate (5–6), and high (≥7). Analyses for BMI status were based on pre-determined BMI categories, normal (<25 kg/m2), overweight (25-<30 kg/m2), and obese (≥30 kg/m2). Because only three women had a BMI <18.5 kg/m2, these participants were excluded from the analyses. An indicator variable with a cut-off of 2.5 μg/mL for hyper γ-tocopherolemic status was created. Means and standard deviations for dietary and lifestyle habits as well as biomarkers were computed by level of adherence and by BMI status. Non-normally distributed variables were log-transformed to obtain p-values for trend tests across categories using analysis of variance. In adjusted models, we included age, parity, ethnicity, and timing of biospecimen collection within the luteal phase (yes or no) as covariates and expressed the differences as least square means with 95% confidence intervals. Finally, we examined the distribution of hyper γ-tocopherolemia by adherence category and computed odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) in a logistic regression model with low adherers as the reference group.

RESULTS

The study population (Table 2) consisted of 41% whites, 36% Asians, 14% Native Hawaiians, and 9% Others with a mean age of 41.9 (SD: 4.5) years. The mean BMI was 26.1 (5.7) kg/m2 with 27% classified as overweight and 22% as obese. Of all biospecimens, 87% were collected during the luteal phase. The majority of participants (Table 1) were never smokers (65%), met the physical activity guideline (65%), and reported drinking ≤1 alcoholic beverage per day (90%). As to nutritional recommendations, 88% adhered to low red/processed meat intake, 71% to low soda intake, but only 48% limited sodium intake to <2400 mg/day, and 32% consumed adequate amounts of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains. The respective means for CRP, γ-tocopherol, and F2-isoprostances were 2.1 mg/L, 1.7 μg/mL, and 14.6 ng/mL. Levels of serum γ-tocopherol and CRP were significantly correlated 0.24 (p=0.001).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of 275 premenopausal women from two intervention studiesa

| Characteristic | BEAN1 & BEAN2 |

|---|---|

| N | 275 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 112 (40.7%) |

| Asian | 99 (36.0%) |

| Native Hawaiian | 38 (13.8%) |

| Other | 26 (9.5%) |

| Age, years | 41.9 (4.5) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.1 (5.7) |

| Parity | |

| No | 204 (74.2%) |

| Yes | 71 (25.8%) |

| Biospecimen collection in luteal phase | |

| No | 37 (13.5%) |

| Yes | 238 (86.5%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 179 (65.1%) |

| Past | 17 (6.2%) |

| Current | 79 (28.7%) |

| Serum C-reactive protein, mg/Lb | 2.1 (3.2) |

| Serum γ-tocopherol, μg/mL b | 1.69 (0.96) |

| Urinary F2-isoprostane, ng/mLb | 14.6 (5.3) |

| Dietary intake from baseline food frequency questionnaire | |

| Total energy, kcal/day | 1911 (893) |

| Red/processed meat, servings/day | 1.3 (1.1) |

| Whole grain, servings/day | 1.9 (1.5) |

| Dietary fiber, g/day | 20.1 (11.6) |

| Total energy from fat, % | 32.6 (6.0) |

| Fruit, servings/day | 1.5 (1.6) |

| Vegetables, servings/day | 3.3 (2.4) |

| Fruit & vegetables, servings/day | 4.8 (3.4) |

| Alcohol, drinks/day | 0.3 (0.6) |

| Regular soda, g/day | 50 (140) |

| Sodium, mg/day | 2781 (1469) |

| Physical activity, hrs/week | 7.7 (8.0) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean (SD). Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Serum γ-tocopherol and CRP were available for BEAN1 only and urinary F2-isoprostane levels for BEAN2 only. Data were missing for serum γ-tocopherol (N=23) and serum CRP (N=12).

Overall, 72 women were classified as low-adherers, 150 as moderate adherers, and 53 as high-adherers (Table 3). The low adherers had a mean BMI of 30.3 (SD: 6.0) kg/m2, while the mean BMI of the high adhering women was 22.2 (2.0) kg/m2. High adherers were also more physically active (ptrend<0.0001), consumed less red/processed meat (ptrend<0.0001), lower percent total energy from fat (ptrend=0.002), less sodium (ptrend<0.0001), and more dietary fiber (ptrend=0.01) and more fruits and vegetables (ptrend=0.002). The unadjusted means for CRP (BEAN1 only) were 2.7, 2.0, and 1.7 mg/L for low, moderate, and high adherers (ptrend=0.03); this association was strengthened after adjustment for potential confounders with least square means for log-transformed CRP values of 1.12, 0.87, and 0.71 mg/L (ptrend=0.006). The respective values for serum γ-tocopherol (BEAN1 only) were 1.97, 1.63, and 1.45 μg/mL (ptrend=0.02) before and 1.10, 0.96, and 0.91 μg/mL (ptrend=0.03) after adjustment. However, for urinary F2-isoprostane (BEAN2 only) the higher values in low adherers (16.0, 14.5, and 13.3 ng/mL) did not reach statistical significance (ptrend=0.18). In the adjusted models, the respective F2-isoprostane values were 2.74, 2.66, and 2.60 ng/mL (ptrend=0.21).

Table 3.

Characteristics of women by adherence to WCRF/AICR recommendationsa

| Low adherence (≤4) | Moderate adherence (5–6) | High adherence (≥7) | P-value, unadjustedc | P-value, adjustedc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 72 | 150 | 53 | ||

| Age, years | 42.8 (3.3) | 41.6 (4.7) | 41.8 (5.0) | 0.15 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.16 | ||||

| White | 23 (31.9%) | 62 (41.3%) | 27 (50.9%) | ||

| Asian | 29 (40.3%) | 51 (34.0%) | 19 (35.9%) | ||

| Native Hawaiian | 12 (16.7%) | 24 (16.0%) | 2 (3.8%) | ||

| Other | 8 (11.1%) | 13 (8.7%) | 5 (9.4%) | ||

| Serum CRP, mg/Lb | 2.7 (3.5) | 2.0 (3.2) | 1.7 (2.7) | 0.03 | 0.006 |

| Serum γ-tocopherol, μg/mLb | 1.97 (1.01) | 1.63 (0.94) | 1.45 (0.83) | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Hyper γ-tocopherolemia (≥2.5 μg/mL) | 12 (25%) | 15 (17%) | 4 (12%) | 0.29 | |

| Urinary F2-isoprostane, ng/mLb | 16.0 (7.2) | 14.5 (4.8) | 13.3 (3.8) | 0.18 | 0.21 |

WCRF/AICR: World Cancer Research Fund & American Institute for Cancer Research. Data are presented as n (%) or mean (SD) unless otherwise noted. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Serum γ-tocopherol and CRP were available for BEAN1 only and urinary F2-isoprostane levels for BEAN2 only. Data were missing for serum γ-tocopherol (N=23) and serum CRP (N=12).

P for trend values were computed for continuous variables using log-transformed data except for age and % total energy from fat. P values for categorical variables were computed using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Adjusted model included age, parity, ethnicity, and timing of biospecimen collection within the luteal phase (yes or no) as covariates.

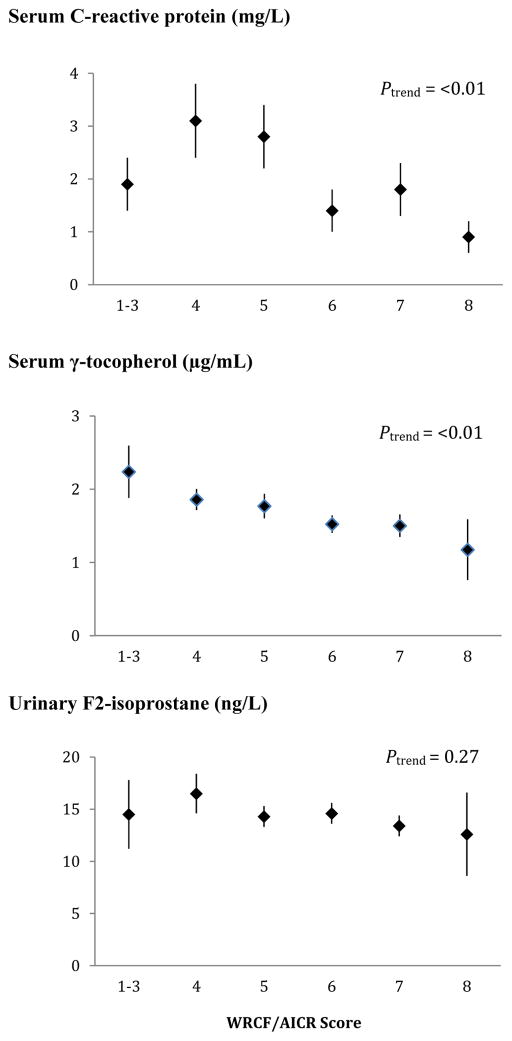

The inverse associations for the biomarkers with higher adherence (Figure 2) were more pronounced for CRP (ptrend<0.01) and γ-tocopherol (ptrend<0.01) than for F2-isoprostane (ptrend=0.27). Whereas the mean levels by adherence score were more or less flat for F2-isoprostane, serum γ-tocopherol showed a continuous decline from >2.0 to <1.5 μg/mL across categories. We observed smaller proportions of women with hyper γ-tocopherolemia among moderate and high adherers than in low adherers (17 and 12% vs. 25%, respectively). However, the respective ORs of 0.60 (95% CI: 0.26, 1.41) and 0.41 (95% CI: 0.12, 1.42) for moderate and high adherers vs. low adherers were not statistically significant. For CRP, the levels were up to twice as high for the three lower categories than for women scoring 6–8.

Figure 2.

Mean biomarker levels and standard errors by World Cancer Research Fund & American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) score. Missing data were recorded for serum γ-tocopherol (N=23) and serum C-reactive protein (N=12). P-for-trend values were computed using log-transformed biomarker levels.

When participants were grouped by BMI category (Table 4), red/processed meat, percent of total energy from fat, and sodium intake were significantly higher and physical activity significantly lower in overweight and obese than normal weight women. AICR scores not including BMI were lowest in the obese group followed by overweight and normal weight women with respective values of 5.7±1.0, 4.8±1.2, and 5.1±1.0. The levels of CRP, γ-tocopherol, and F2-isoprostane were substantially higher in overweight and obese than normal weight women; these trends remained unchanged after adjustment for age, ethnicity, parity, and luteal phase. However, the linear trend was only statistically significant for CRP and γ-tocopherol with log-transformed values of 0.56. 0.96, and 1.38 (ptrend<0.0001) and 7.20, 7.40, and 7.55 (ptrend=0.008), respectively. The respective least square means for F2-isoprostane were 2.64, 2.57, and 2.83 (ptrend=0.21) across BMI categories.

Table 4.

Characteristics of women by body mass index (BMI) categorya

| Normal (18.5-<25.0 kg/m2) | Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | Obese (>30 kg/m2) | P-value, unadjustedd | P-value, adjustedd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 138 | 74 | 60 | ||

| Age | 41.6 (4.7) | 42.6 (3.9) | 41.7 (4.6) | 0.62 | |

| Smoking status | 0.13 | ||||

| Never | 96 (68.1%) | 48 (64.8%) | 35 (58.3%) | ||

| Past | 9 (6.4%) | 7 (95%) | 1 (1.7%) | ||

| Current | 36 (25.5%) | 19 (25.7%) | 24 (40.0%) | ||

| Serum CRP, mg/Lb | 1.0 (1.1) | 2.3 (2.8) | 4.7 (4.9) | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Serum γ-tocopherol, μg/mLb | 1.49 (0.91) | 1.79 (1.04) | 2.00 (0.88) | 0.003 | 0.008 |

| Urinary F2-isoprostane, ng/mLb | 14.2 (4.6) | 13.6 (5.0) | 17.4 (6.9) | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| Dietary intakes from baseline food frequency questionnaire | |||||

| Total energy, Kcal/day | 1810 (887) | 1944 (798) | 2069 (1001) | 0.10 | |

| Red/processed meat, servings/day | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.0) | <0.0001 | |

| Whole grains, servings/day | 1.6 (1.8) | 1.8 (1.6) | 1.8 (1.6) | 0.44 | |

| Dietary fiber, g/day | 20.7 (12.8) | 19.4 (9.3) | 19.4 (11.5) | 0.49 | |

| Total energy from fat, % | 31.2 (6.0) | 34.1 (5.1) | 34.1 (6.3) | 0.0003 | |

| Fruit, servings/day | 1.6 (1.8) | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.2) | 0.18 | |

| Vegetables, servings/day | 3.4 (2.7) | 3.4 (2.2) | 2.9 (1.7) | 0.31 | |

| Fruit & vegetables, servings/day | 5.0 (4.0) | 4.9 (3.0) | 4.2 (2.6) | 0.18 | |

| Alcohol, drinks/day | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.17 | |

| Regular soda, g/day | 58 (179) | 30 (68) | 61 (99) | 0.18 | |

| Sodium, mg/day | 2679 (1557) | 2672 (1294) | 3162 (1457) | 0.01 | |

| Physical activity, hrs/week | 8.9 (8.7) | 7.1 (6.8) | 5.7 (7.1) | 0.001 | |

| WCRF/AICR score without BMIc | 5.1 (1.0) | 4.8 (1.2) | 4.3 (1.0) | <0.0001 | |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean (SD) unless otherwise noted. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding. Three women with a BMI <18.5 kg/m2 were not included in the analysis.

Serum γ-tocopherol and C-reactive protein levels are available for BEAN1 only and urinary F2-isoprostane levels are available for BEAN2 only. Missing data were recorded for serum γ-tocopherol (N=23) and Serum C-reactive protein (N-12).

WCRF/AICR: World Cancer Research Fund & American Institute for Cancer Research; body mass index (BMI) individual score was removed from the AICR score.

P for trend values were computed for continuous variables using log-transformed data except for age and % total energy from fat. P values for categorical variables were computed using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Adjusted model included age, parity, ethnicity, and timing of biospecimen collection within the luteal phase (yes or no) as covariates.

DISCUSSION

In this study of multiethnic premenopausal women, many women met a high proportion of the 8 recommendations operationalized according to the WCRF/AICR cancer prevention guidelines, in particular limiting the consumption of energy dense food such as sodas, red/processed meat, and alcohol. Women with lower adherence scores had a higher BMI and reported higher intakes of unfavorable foods and behaviors. The results of this study suggest a weak inverse relation between adherence to nutritional and lifestyle recommendations and two of the three markers of antioxidant and inflammatory status examined. Specifically, γ-tocopherol and CRP but not F2-isoprostane, were lower in women with higher adherence scores. In a similar pattern, overweight and obese women had substantially higher levels of all three biomarkers than normal weight women; in particular CRP was nearly 5-fold higher in obese women. In response to the inflammatory stress marked by low adherence scores and excess body weight, γ-tocopherol appears to rise as a physiological mechanism to protect the body against inflammation-related damage. Although a well-established marker of inflammation, urinary F2-isoprostane showed little association with adherence scores and BMI status.

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to examine the association between WCRF/AICR recommendations and biomarkers of inflammation and antioxidant status. Previous studies investigated adherence to WCRF/AICR recommendations with morbidity and mortality in women. For example, a 22–24% lower cancer-specific mortality for meeting 1–2 recommendations and 61% lower for meeting 5–6 recommendations were reported(3). A larger cohort observed similar results with a 34% lower mortality for individuals who met 6–7 recommendations(2). The association between excess body weight and elevated CRP levels is well known and has been described for many populations(33, 34).

The association of overweight with the biomarkers may be due to cytokines produced in adipose tissue or due to direct effects of dietary components associated with a high BMI. For example, obese women consumed more red/processed meat, fat, and sodium, food components that were related to higher γ-tocopherol in a previous report(35). While dietary intake of γ-tocopherol and blood levels are poorly correlated(36–39), red/processed meat consumption is thought to be related to inflammatory responses during digestion, which may lead to an increase in circulating γ-tocopherols(40). The stimulation of inflammatory cytokines by excess adiposity may also influence γ-tocopherol levels(20, 41). Among antioxidants, γ-tocopherol appears to be unique in that higher circulating levels are directly associated with oxidative stress, whereas most antioxidants are reduced under conditions of oxidative stress(18, 19). The wide range of adverse conditions associated with elevated γ-tocopherol, and the general correlation with risk factors in the present study indicate it may be a useful integrative marker for assessing future disease risk. The occurrence of hyper γ-tocopherolemia was weakly related to lower overall adherence scores without reaching statistical significance, suggesting a higher cutoff for defining this state might be indicated. Since very few supplements contain γ-tocopherol, it is unlikely that high circulating γ-tocopherol levels are due to supplement intake. While γ-tocopherol accounts for 80% of tocopherols in the diet, most is excreted or metabolized in healthy people(36, 39).

Strengths of the present study include the ethnic diversity of the women, as well as the use of a previously-validated FFQ(26). We analyzed baseline nutritional data prior to implementation of the study interventions, thereby capturing usual dietary and lifestyle habits from the year before dietary changes were initiated. Given the generally good health status of the participants, it is unlikely that unknown, underlying conditions affected the biomarker levels. On the other hand, given the healthy status of the women, their high adherence to lifestyle recommendations, and the strict eligibility criteria, the participants probably represented a relatively narrow range in biomarker levels. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to a population with a higher prevalence of chronic conditions. The study was also limited by the small sample size and the low statistical power, the lack of a general energy-density variable, and the absence of information on dietary supplement intake.

Diet-disease associations are difficult to determine due to the length of time required for quantifiable symptoms to be expressed and chronic diseases to develop. Elevated levels of biomarkers in healthy people may help to identify persons at a higher risk for chronic disease development later in life. The fact that WCRF/AICR adherence scores and BMI status showed similar associations with the three biomarkers suggests that the type of foods consumed may be less important in determining future disease risk than the excess body weight resulting from poor dietary patterns. The current findings suggest that adherence to the WCRF/AICR guidelines is associated with lower levels of biomarkers that indicate oxidative stress and inflammatory status, in particular serum CRP and γ-tocopherol, and may lower future disease risk.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the dedicated study participants.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This work was supported by grants R01CA80843 (PI: G. Maskarinec) and P30CA71789 (PI: M. Carbone) from the National Cancer Institute. The funding agency had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this article.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP

G. M. conceived the original studies, obtained funding, supervised the data analysis and finalized the manuscript. R.V.C. and A.A.F. provided laboratory results and interpreted the results. Y.M. and F.B. collated the statistical information and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the findings of the study.

References

- 1.World Cancer Research Fund. WCRF/AICR Expert Report, Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vergnaud AC, Romaguera D, Peeters PH, et al. Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research guidelines and risk of death in Europe: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Nutrition and Cancer cohort study1,4. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:1107–1120. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.049569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hastert TA, Beresford SA, Sheppard L, et al. Adherence to the WCRF/AICR cancer prevention recommendations and cancer-specific mortality: results from the Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:541–552. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0358-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi AK, Moore SC, Hildesheim A. Invited commentary: circulating inflammation markers and cancer risk--implications for epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:14–19. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albers R, Antoine JM, Bourdet-Sicard R, et al. Markers to measure immunomodulation in human nutrition intervention studies. Br J Nutr. 2005;94:452–481. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ollberding NJ, Kim Y, Shvetsov YB, et al. Prediagnostic leptin, adiponectin, C-reactive protein, and the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6:188–195. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooney RV, Chai W, Franke AA, et al. C-reactive protein, lipid-soluble micronutrients, and survival in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1278–1288. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magalhaes LM, Segundo MA, Reis S, et al. Methodological aspects about in vitro evaluation of antioxidant properties. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;613:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsimikas S. Measures of oxidative stress. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26:571–5vi. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cracowski JL, Durand T, Bessard G. Isoprostanes as a biomarker of lipid peroxidation in humans: physiology, pharmacology and clinical implications. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:360–366. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ju J, Picinich SC, Yang Z, et al. Cancer-preventive activities of tocopherols and tocotrienols. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:533–542. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Constantinou C, Papas A, Constantinou AI. Vitamin E and cancer: An insight into the anticancer activities of vitamin E isomers and analogs. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:739–752. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooney RV, Franke AA, Harwood PJ, et al. Gamma-tocopherol detoxification of nitrogen dioxide: superiority to alpha-tocopherol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1771–1775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christen S, Woodall AA, Shigenaga MK, et al. gamma-tocopherol traps mutagenic electrophiles such as NO(X) and complements alpha-tocopherol: physiological implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3217–3222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka Y, Cooney RV. Chemical and biologic properties of tocopherols and their relation to cancer incidence and progression. In: Preedy V, Watson R, editors. The Encyclopedia of Vitamin E. New Yort: CABI Publishing; 2007. pp. 853–863. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Q, Ames BN. Gamma-tocopherol, but not alpha-tocopherol, decreases proinflammatory eicosanoids and inflammation damage in rats. FASEB J. 2003;17:816–822. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0877com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang Q, Lykkesfeldt J, Shigenaga MK, et al. Gamma-tocopherol supplementation inhibits protein nitration and ascorbate oxidation in rats with inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1534–1542. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka Y, Wood LA, Cooney RV. Enhancement of intracellular gamma-tocopherol levels in cytokine-stimulated C3H 10T1/2 fibroblasts: relation to NO synthesis, isoprostane formation, and tocopherol oxidation. BMC Chem Biol. 2007;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6769-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooney RV, Franke AA, Wilkens LR, et al. Elevated plasma gamma-tocopherol and decreased alpha-tocopherol in men are associated with inflammatory markers and decreased plasma 25-OH vitamin D. Nutr Cancer. 2008;60(Suppl 1):21–29. doi: 10.1080/01635580802404162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chai W, Bostick RM, Ahearn TU, et al. Effects of vitamin D3 and calcium supplementation on serum levels of tocopherols, retinol, and specific vitamin D metabolites. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64:57–64. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.630552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chai W, Maskarinec G, Cooney RV. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and mammographic density among premenopausal women in a multiethnic population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:652–654. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chai W, Novotny R, Maskarinec G, et al. Serum coenzyme Q(1)(0), alpha-tocopherol, gamma-tocopherol, and C-reactive protein levels and body mass index in adolescent and premenopausal females. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33:192–197. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2013.862490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maskarinec G, Franke AA, Williams AE, et al. Effects of a 2-year randomized soy intervention on sex hormone levels in premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1736–1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maskarinec G, Morimoto Y, Conroy SM, et al. The volume of nipple aspirate fluid is not affected by 6 months of treatment with soy foods in premenopausal women. J Nutr. 2011;141:626–630. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.133769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stram DO, Hankin JH, Wilkens LR, et al. Calibration of the dietary questionnaire for a multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:358–370. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy SP. Unique nutrition support for research at the Cancer Research Center of Hawaii. Hawaii Med J. 2002;61:15, 17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma S, Murphy SP, Wilkens LR, et al. Extending a multiethnic food composition table to include standardized food group servings. J Food Composition Analysis. 2003;16:485–495. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maskarinec G, Steude JS, Franke AA, et al. Inflammatory markers in a 2-year soy intervention among premenopausal women. J Inflamm (Lond) 2009;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franke AA, Custer LJ, Cooney RV. Synthetic carotenoids as internal standards for plasma micronutrient analysis by HPLC. J Chromatography B. 1993;614:43–57. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)80222-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franke AA, Cooney RV, Henning SM, et al. Bioavailability and antioxidant effects of orange juice components in humans. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:5170–5178. doi: 10.1021/jf050054y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sen C, Morimoto Y, Heak S, et al. Soy foods and urinary isoprostanes: results from a randomized study in premenopausal women. Food Funct. 2012;3:517–521. doi: 10.1039/c2fo10251j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das UN. Is obesity an inflammatory condition? Nutrition. 2001;17:953–966. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fogarty AW, Glancy C, Jones S, et al. A prospective study of weight change and systemic inflammation over 9 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:30–35. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fung TT, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, et al. Association between dietary patterns and plasma biomarkers of obesity and cardiovascular disease risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:61–67. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Institute of Medicine FaNB. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids. 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Office of Dietary Supplements NIoH. Dietary supplement fact sheet: Vitamin E. 2011 http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminE-HealthProfessional/

- 38.Dietrich M, Traber MG, Jacques PF, et al. Does gamma-tocopherol play a role in the primary prevention of heart disease and cancer? A review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25:292–299. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herrera E, Barbas C. Vitamin E: action, metabolism and perspectives. J Physiol Biochem. 2001;57:43–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montonen J, Boeing H, Fritsche A, et al. Consumption of red meat and whole-grain bread in relation to biomarkers of obesity, inflammation, glucose metabolism and oxidative stress. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52:337–345. doi: 10.1007/s00394-012-0340-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allin KH, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated C-reactive protein in the diagnosis, prognosis, and cause of cancer. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2011;48:155–170. doi: 10.3109/10408363.2011.599831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]