Abstract

Efficient cryopreservation of cells at ultralow temperatures requires the use of substances that help maintain viability and metabolic functions post‐thaw. We are developing new technology where plant proteins are used to substitute the commonly‐used, but relatively toxic chemical dimethyl sulfoxide. Recombinant forms of four structurally diverse wheat proteins, TaIRI‐2 (ice recrystallization inhibition), TaBAS1 (2‐Cys peroxiredoxin), WCS120 (dehydrin), and TaENO (enolase) can efficiently cryopreserve hepatocytes and insulin‐secreting INS832/13 cells. This study shows that TaIRI‐2 and TaENO are internalized during the freeze–thaw process, while TaBAS1 and WCS120 remain at the extracellular level. Possible antifreeze activity of the four proteins was assessed. The “splat cooling” method for quantifying ice recrystallization inhibition activity (a property that characterizes antifreeze proteins) revealed that TaIRI‐2 and TaENO are more potent than TaBAS1 and WCS120. Because of their ability to inhibit ice recrystallization, the wheat recombinant proteins TaIRI‐2 and TaENO are promising candidates and could prove useful to improve cryopreservation protocols for hepatocytes and insulin‐secreting cells, and possibly other cell types. TaENO does not have typical ice‐binding domains, and the TargetFreeze tool did not predict an antifreeze capacity, suggesting the existence of nontypical antifreeze domains. The fact that TaBAS1 is an efficient cryoprotectant but does not show antifreeze activity indicates a different mechanism of action. The cryoprotective properties conferred by WCS120 depend on biochemical properties that remain to be determined. Overall, our results show that the proteins' efficiencies vary between cell types, and confirm that a combination of different protection mechanisms is needed to successfully cryopreserve mammalian cells.

Keywords: cryopreservation, plant protein, ice recrystallization inhibition, mammalian cell

Introduction

The transplantation of cells such as hepatocytes1, 2 and pancreatic islets3, 4 is currently being used in clinics as an alternative approach to whole organ transplantation. These approaches are safer and take away the burden of major surgery for patients. In addition, hepatocytes are being used increasingly as cellular models for in vitro drug cytotoxicity testing.5 They are considered to be a reliable indicator of human toxicity during early stages of drug development. Drug‐induced liver injury accounts for the majority of cases of acute liver failure and is a major public health problem in many countries.6 It is costly to the pharmaceutical industry and is one of the most frequent reasons for the withdrawal of an approved drug.5, 7 Therefore, there is an ever‐increasing demand for the availability of cells such as hepatocytes and pancreatic islets.

Cryopreservation, which involves the use of very low subzero temperatures (<−80°C), remains the most common method for long‐term storage of cells and tissues. However, during cryopreservation, cells experience irreparable damage caused by the freezing and thawing process, resulting in reduced post‐thaw cellular integrity.8, 9 Consequently, damaged cells are unable to resume proliferative and metabolic activities after thawing. A major source of cryoinjury associated with poor post‐thaw viabilities in many different cell types is uncontrolled ice growth, a phenomenon called recrystallization.8, 9 Ice recrystallization (IR) is the thermodynamically favoured growth of large ice crystals at the expense of smaller ones and this phenomenon is implicated particularly in the thawing phase of cryopreservation.10 Proteins and other compounds that inhibit this process, ice recrystallization inhibitors (IRI), are necessary to prevent cellular damage during cryopreservation.

Cryopreservation of cells and tissues requires the use of cryoprotectants to alleviate the cellular damage occurring during freezing and thawing. Commonly used cryoprotectants include cell‐permeable substances such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), glycerol and 1,2‐propanediol, and various polymers such as hydroxyethyl starch and polyvinyl pyrrolidone.11 These cryoprotectants reduce cryoinjury by stabilizing cell membranes and mitigating osmotic imbalances. However, there are several drawbacks associated with their use. Firstly, cryoprotectants can interfere with cell‐specific metabolic functions such as insulin secretion by pancreatic β cells and cytochrome P450 metabolism in hepatocytes. Secondly, cell‐permeable cryoprotectants need to be used at high concentrations and this is often associated with toxic effects in cells and tissues. Consequently, they need to be removed from transplant material to avoid toxic reactions in patients. These washing procedures are often extremely laborious and time‐consuming and reduce the number of cells available for transplant. Thirdly, the effectiveness of nonpermeating cryoprotectants is generally limited to narrow and specific cooling/thawing ranges, which restricts their use in clinical settings. Ironically, despite the fact that the uncontrolled growth of ice is directly responsible for the cellular damage associated with cryopreservation, clinically used cryoprotectants fail to efficiently control the growth of ice and recrystallization.

Over the past 15 years, various naturally occurring biological antifreezes having the ability to control ice growth have been investigated as cryoprotectants, but generally very poor outcomes have been observed. Antifreeze proteins and antifreeze glycoproteins (AF(G)Ps) are naturally occurring proteins found in several plant, insect and fish species that provide protection to organisms which inhabit subzero environments.12 AF(G)Ps possess two distinct antifreeze properties—IRI activity (discussed above) and thermal hysteresis (TH) activity. TH is defined as the localized freezing point depression relative to the melting point. The temperature difference is referred to as the TH gap during which ice growth is suppressed. However, at temperatures outside the TH gap (such as those used during cryopreservation), ice growth will resume uncontrollably in the form of spicules.12 This is the reason why AF(G)Ps are poor cryoprotectants and actually increase cryoinjury. Therefore, proteins or molecules which possess IRI activity and which do not possess TH activity show properties that are desirable for a good cryoprotectant.

Given the limitations of currently used cryoprotectants, development of new approaches for the long‐term cryostorage of cells and tissues for clinical applications and drug‐toxicity testing is essential. Towards this goal, we have developed a new technology for the cryopreservation of mammalian cells using proteins produced by plants that tolerate freezing conditions. Hardy varieties of winter wheat are more resistant to extreme freezing conditions compared to their spring counterparts.13 Soluble protein extracts (WPE) from winter wheat were able to successfully cryopreserve hepatocytes14, 15, 16 and insulin‐secreting pancreatic cells.17 The WPE contains a mixture of thousands of different proteins. For identification of cryoactive candidates present in wheat, we first selected proteins known for their association with freezing tolerance. Among these, the recombinant WCS120 dehydrin18 and the TaIRI‐2 ice recrystallization inhibition protein19 proved efficient in cryopreserving several mammalian cell types. To identify novel cryoactive proteins, the wheat protein extracts (WPE) were separated by chromatography and cryoactive fractions were analysed by mass spectrometry. Two additional candidate cryoactive plant proteins were revealed, enolase (TaENO)20 and the 2‐Cys peroxiredoxin BAS1 (renamed TaBAS1).21

The mechanisms by which the WCS120, TaIRI‐2, TaENO, and TaBAS1 plant proteins protect mammalian cells during freezing are not clearly understood. However, it is likely that they protect cells against cryoinjury by multiple mechanisms. This study investigates the physicochemical properties of the four recombinant wheat proteins. The goal was to determine if the proteins act at the intracellular or extracellular level, and whether their cryoprotective activity in rat hepatocytes and insulin‐secreting cells is a result of TH or IRI activities. Elucidating these properties will guide us in developing an optimized cryopreservation medium and procedure to further improve post‐thaw viability and metabolic functions of hepatocytes and insulin‐secreting cells.

Results

Internalization study of fluorescently labeled wheat recombinant proteins in hepatocytes and INS832/13 cells

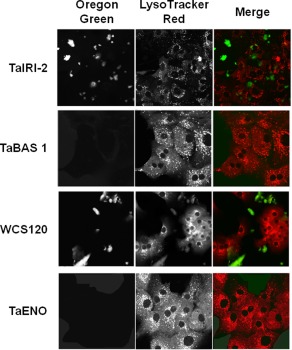

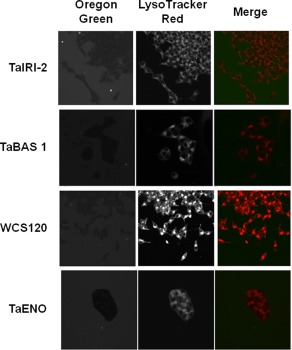

We reported that the wheat proteins WCS120, TaIRI‐2, TaENO, and TaBAS1 showed promising potential for the cryopreservation of hepatocytes and insulin‐secreting cells, but it was unclear if the cryoprotective effects occurred at the intracellular or extracellular level. Given that these proteins are quite big with MWs of 40.7 kDa for TaIRI‐2, 23 kDa for truncated TaBAS1, 39 kDa for WCS120, and 48 kDa for TaENO, it is not certain if they could cross the cytoplasmic membrane and enter cells, either by passive diffusion or endocytosis. Therefore, internalization studies were conducted in hepatocytes (Fig. 1) and INS832/13 cells (Fig. 2) using recombinant wheat proteins that were labeled with Oregon Green 488. Cells were incubated for 30 min at 22°C with each of the fluorescently labeled proteins (left panels) and with LysoTracker Red as a counterstain for lysosomes (middle panels). Images were analyzed by confocal microscopy and merged images (right panels) show that the four proteins remain outside of the two cell types prior to freezing. When hepatocytes were incubated with labeled TaIRI‐2 or WCS120, these proteins formed large aggregates that remained outside of cells and in proximity to the cytoplasmic membrane (Fig. 1). Aggregation did not occur with TaBAS1 or TaENO, which could be seen as a pale green fluorescent background outside of the cells (Fig. 1). When INS832/13 cells were incubated with the labeled proteins, aggregation did not occur and there was a pale green extracellular fluorescent background for each of the proteins (Fig. 2). As a positive control for internalization by endocytosis, cells were incubated with the fluorescent probe pHrodo Green Dextran, using LysoTracker Red as a counterstain. Analysis by confocal microscopy confirmed internalization of the green fluorescence by hepatocytes and INS832/13 cells after 3 min, and colocalization of green fluorescence with red fluorescence for lysosomes (Supporting Information Fig. S1). This indicates that cellular integrity was intact.

Figure 1.

Internalization study of recombinant wheat proteins in hepatocytes. Confocal fluorescence microscopy images of hepatocytes after 30 min of incubation with Oregon green‐labeled recombinant wheat proteins TaIRI‐2, TaBAS1, WCS120, and TaENO (left panels). Lysosomes were stained with LysoTracker Red (middle panels). Merged images of labeled proteins and lysosomes are shown (right panels). Representative images (200×) are from at least three different preparations of proteins tested on five independent cell preparations.

Figure 2.

Internalization study of recombinant wheat proteins in INS832/13 cells. Confocal microscopy images of INS832/13 cells after 30 min of incubation with Oregon green‐labeled recombinant proteins (left panels) and LysoTracker Red (middle panels). Merged images of labeled proteins and lysosomes are shown (right panels). Representative images (400×) are from at least three different preparations of proteins tested on five independent cell preparations.

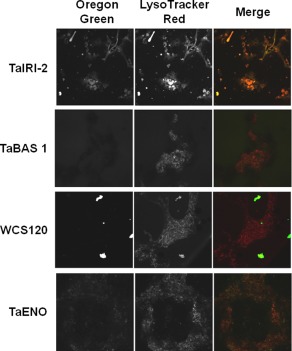

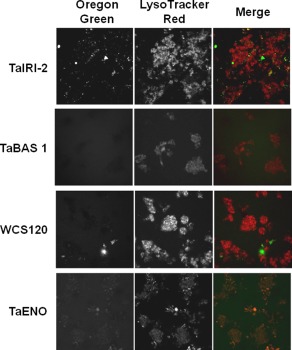

Given that cryopreservation can affect cell membranes,22 we determined if the cryopreservation procedure could affect internalization of the recombinant wheat proteins. Cells were first incubated with LysoTracker Red, fluorescently‐labeled proteins were added, and the mixtures were subjected to our freezing protocol. Confocal microscopy analysis after thawing showed that TaIRI‐2 and TaENO are found inside hepatocytes (Fig. 3) and INS832/13 cells (Fig. 4) after thawing, as revealed by the colocalization of red and green fluorescence (merged images, right panels).

Figure 3.

Internalization study of recombinant wheat proteins in hepatocytes after thawing. Hepatocytes were incubated with LysoTracker Red and Oregon green‐labeled recombinant wheat proteins TaIRI‐2, TaBAS1, WCS120, and TaENO, and then were frozen. After thawing, lysosomes (middle panels) and fluorescent proteins (left panels) were detected by confocal microscopy. Merged images are shown (right panels). Representative images (200×) are from at least three different preparations of proteins tested on five independent cell preparations.

Figure 4.

Internalization study of recombinant wheat proteins in INS832/13 cells after thawing. INS832/13 cells were incubated with LysoTracker Red and Oregon green‐labeled recombinant wheat proteins TaIRI‐2, TaBAS1, WCS120, and TaENO, and then were frozen. After thawing, lysosomes (middle panels) and fluorescent proteins (left panels) were detected by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Merged images are shown (right panels). Representative images (400×) are from at least three different preparations of proteins tested on five independent cell preparations.

Ice recrystallization inhibition (IRI) and thermal hysteresis (TH) of wheat proteins

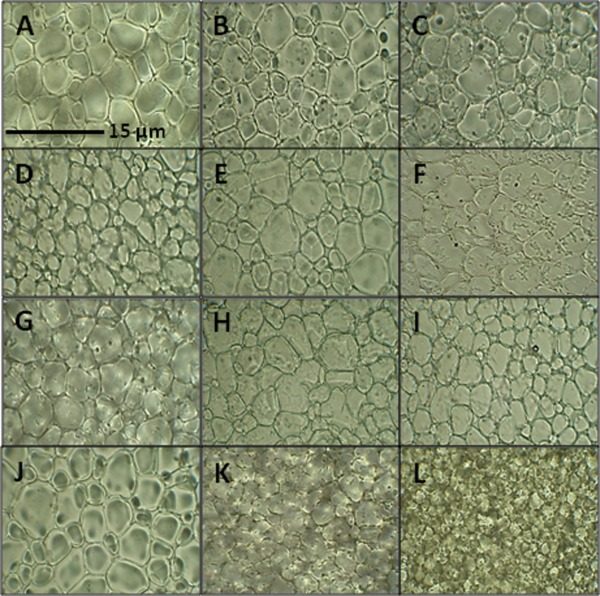

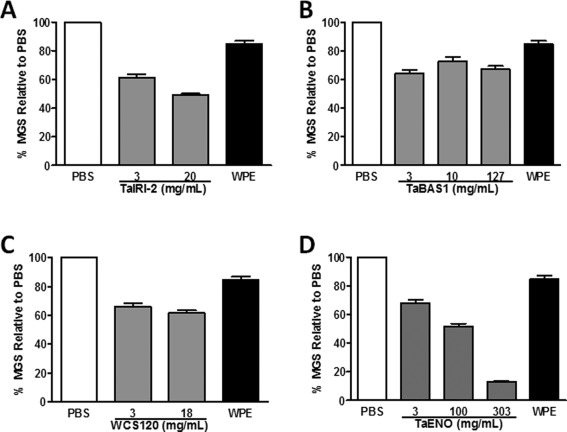

The observation that the four recombinant proteins confer cryoprotection to hepatocytes and INS832/13 cells led us to investigate whether they possess IRI or TH properties. With respect to ice recrystallization, the WPE (3 mg/mL) only caused a slight decrease in the MGS of ice crystals [84.6%; Figs. 5(B) and Fig. 6(A)] compared to the PBS control [Fig. 5(A)]. Regardless of the concentration used, TaBAS1 [Figs. 5(E–G) and 6(B)] and WCS120 [Figs. 5(H–I) and 6(C)] provided modest IRI activity as determined by a MGS between 60 and 70%. TaIRI‐2 at 20 mg/mL [Fig. 5(D) and 6(A)] and 100 mg/mL TaENO [Figs. 5(K) and 6(D)] were more IRI‐active than TaBAS1 and WCS120, decreasing the MGS to 48.9 and 51.8%, respectively, compared to the PBS control. At very high concentration, TaENO (303 mg/mL) exhibited potent IRI activity, as reflected by the very low MGS of 13.2% [Fig. 5(L) and 6(D)].

Figure 5.

Wheat proteins modify ice recrystallization. Light microscope images of ice crystals in the presence of different wheat proteins prepared in PBS following splat‐cooling assay. (A) PBS control solution, (B) WPE—3 mg/mL, (C) TaIRI‐2—3 mg/mL, (D) TaIRI‐2—20 mg/mL, (E) TaBAS1—3 mg/mL, (F) TaBAS1—10 mg/mL, (G) TaBAS1—127 mg/mL, (H) WCS120—3 mg/mL, (I) WCS120—18 mg/mL, (J) TaENO—3 mg/mL, (K) TaENO—100 mg/mL, (L) TaENO—303 mg/mL. Representative images are from three independent experiments.

Figure 6.

IRI activity of wheat proteins. The y axis represents the percent mean grain size (% MGS) of ice crystals formed in the presence of proteins dissolved in PBS at the indicated concentrations, relative to the crystals formed in PBS alone. Data represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments. The % MGS for all protein concentrations is significantly different (P < 0.05) relative to PBS.

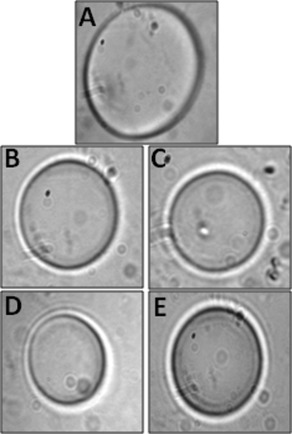

All of the four wheat proteins were investigated for TH activity. Importantly, none of the four proteins or the WPE possessed TH activity (Fig. 7). In addition, none of the four proteins exhibited dynamic ice shaping abilities indicating that they did not bind or interact directly with the surface of ice.

Figure 7.

The wheat proteins do not possess thermal hysteresis capacity. Ice crystal morphologies of water in the presence of (A) WPE—2.5 mg/mL, (B) TaIRI‐2—3.3 mg/mL, (C) TaBAS1—10.0 mg/mL, (D) WCS120–10.0 mg/mL, or (E) TaENO—10.0 mg/mL.

Post‐thaw viability of rat hepatocytes and insulin‐secreting INS832/13 cells cryopreserved with plant proteins

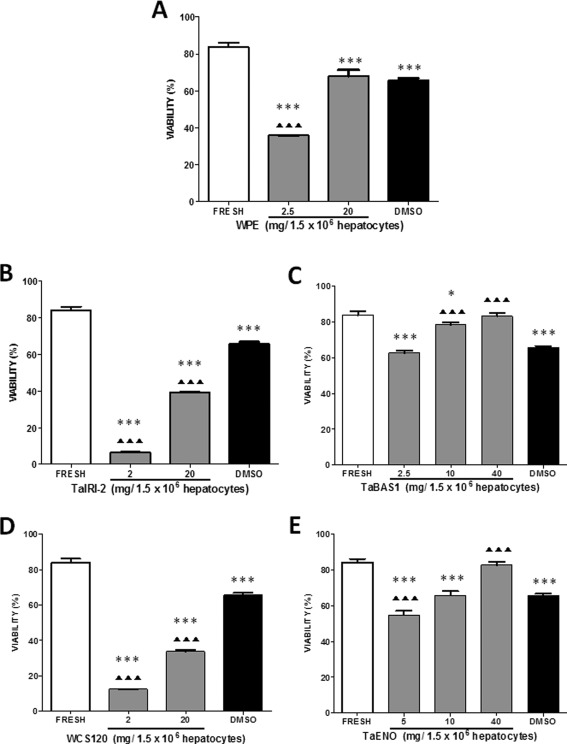

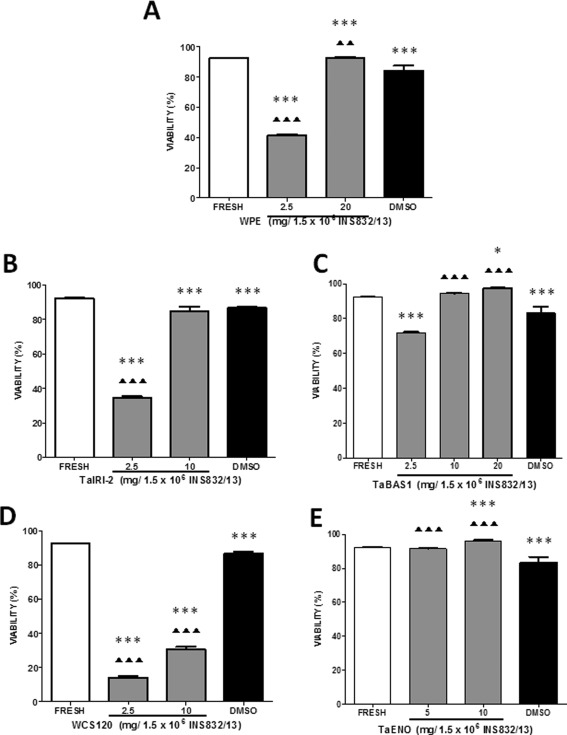

We subsequently determined whether the protein concentrations that revealed IRI activity (Fig. 6) could provide cryoprotection in hepatocytes and INS832/13 cells. Post‐thaw viability was evaluated following cryopreservation with the WPE or each of the four recombinant wheat proteins. Consistent with the lack of IRI activity (Fig. 6), the WPE used at 2.5 mg/1.5 × 106 cells provided low post‐thaw viability of 36 and 41% in hepatocytes and INS832/13 cells, respectively [Figs. 8(A) and 9(A)]. A higher concentration of 20 mg/1.5 × 106 cells provided post‐thaw viabilities that were at least as efficient as DMSO for the two cell types [Figs. 8(A) and 9(A)]. TaIRI‐2 proved to be an efficient cryoprotectant at 10 mg/1.5 × 106 INS832/13 cells (85% post‐thaw viability) [Fig. 9(B)]. However, TaIRI‐2 was not very effective in hepatocytes [Fig. 8(B)]. TaBAS1, used at ≥ 10 mg/1.5 × 106 cells, provided high levels of post‐thaw viability (above 78%) exceeding that for DMSO in both cell types [Figs. 8(C) and 9(C)]. WCS120 was the least effective protein for cryopreservation, as shown by post‐thaw viabilities of 34 and 31% for 20 and 10 mg/1.5 × 106 cells, respectively [Figs. 8(D) and 9(D)]. TaENO was highly efficient for cryopreservation of hepatocytes, providing 83% post‐thaw viability with 40 mg/1.5 × 106 cells [Fig. 8(E)]. TaENO proved even more effective with INS832/13 cells. Post‐thaw viability reached 91% for as low as 5 mg/1.5 × 106 cells [Fig. 9(E)].

Figure 8.

Viability of rat hepatocytes following cryopreservation with different wheat proteins. Hepatocytes were cryopreserved for 7 days with different quantities of (A) wheat protein extract (WPE), or the recombinant proteins (B) TaIRI‐2, (C) TaBAS1, (D) WCS120, or (E) TaENO. Fresh cells served as controls and DMSO (15% + 50% fetal bovine serum (FBS)) as a reference cryoprotectant. Data for post‐thaw viability represent means ± SEM of at least three different preparations of proteins tested on three independent cell preparations. *(P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), ***(P < 0.005): significant difference between cryopreserved cells, and fresh cell controls. ▲(P < 0.05), ▲▲(P < 0.01), ▲▲▲(P < 0.005): significant difference between cells cryopreserved with protein versus DMSO.

Figure 9.

Viability of INS832/13 cells after cryopreservation with wheat proteins. INS832/13 cells were cryopreserved for 7 days with different quantities of (A) wheat protein extract (WPE), (B) TaIRI‐2, (C) TaBAS1, (D) WCS120, or (E) TaENO. Fresh cells served as controls and DMSO (10% + 50% FBS) as a reference cryoprotectant. Data for post‐thaw viability represent means ± SEM of at least three different preparations of proteins tested on three independent cell preparations *(P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), ***(P < 0.005): significant difference between cryopreserved cells and fresh cells. ▲(P < 0.05), ▲▲(P < 0.01), ▲▲▲(P < 0.005): significant difference between cells cryopreserved with protein versus DMSO.

Viability assays could not be performed with the highest protein concentrations used in the IRI assays (PBS buffer) due to a lower solubility of proteins in the WME culture medium used during cryopreservation and viability tests. To rule out a possible effect of the WME culture medium on IRI activity, assays were also performed in WME. For TaBAS1 and TaENO, there was no clear difference between the MGS of crystals observed in WME (Supporting Information Fig. S2) compared to PBS (Fig. 5). Therefore, a possible effect of the culture medium on ice crystal growth can be ruled out, supporting that the IRI effect is probably due to the presence of the recombinant proteins. Overall, these results suggest that there is a lack of correlation between the protein concentrations that exhibited efficient IRI activity and those that were effective in cell cryopreservation.

Discussion

The four wheat proteins used in this study were chosen because of the diversity in their structure and anticipated molecular functions. TaENO and TaBAS1 were shown to be highly effective cryoprotectants for both hepatocytes and insulin‐secreting INS832/13 cells.20, 21 TaIRI‐2 was an effective cryoprotectant in INS832/13 cells, but not in hepatocytes [compare Figs. 8(B) and 9(B)]. Much lower viability was obtained for 2 mg TaIRI‐2/1.5 × 106 hepatocytes [Fig. 8(B)] compared to that obtained with a similar quantity of 2.5 mg TaIRI‐2/1.5 × 106 INS832/13 cells [Fig. 9(B)]. WCS120 was not particularly efficient in either cell type. However, when used together, TaIRI‐2 and WCS120 were able to efficiently cryoprotect hepatocytes.14 The fact that efficiency varies between different cell types suggests that diverse protective mechanisms and cellular structural properties (likely at the plasma membrane level) could be involved in cryoprotection. This could also be due to differences in osmotic tolerance between cell types. Other wheat proteins tested such as the chloroplastic dehydrin WCS19, the plasma membrane‐associated acidic dehydrin WCOR410 and the stress‐induced lipocalin TaTIL or bovine serum albumin (BSA) did not provide cryoprotection in hepatocytes.14 We therefore concluded that the efficiency of the wheat proteins discussed here does not result from unspecific protein effects, but rather is due to their inherent biochemical properties. These observations provided an excellent means to study the involvement of the four wheat proteins in the protection against freeze–thaw damage and/or in the repair mechanisms needed to recover from freezing injury.

This study shows that the four wheat proteins do not enter cells during the preincubation step prior to cryopreservation. However, TaIRI‐2 and TaENO entered cells at some point during the freezing and/or thawing processes. This was an unexpected but interesting finding since both intracellular and extracellular mechanisms could be involved in protection against freeze‐thaw damage. At the intracellular level, TaIRI‐2 and TaENO could provide protection through their ability to decrease the growth of ice crystals, thus preventing potential damage to organelles and other structures. Further investigation will be required to determine the protective mechanism(s) involved at the intracellular level. The protection conferred at the extracellular level by TaBAS1 and possibly the TaENO and TaIRI‐2 proteins was expected since in plants, a high antifreeze activity is found in the apoplastic space of cells in freezing tolerant plants, indicating that extracellular protection mechanisms are needed to minimize freezing‐induced injuries.23 This extracellular antifreeze activity is provided by several proteins, including bona fide antifreeze proteins and others with quite diverse structural properties such as glucanases.

Amino acid sequences of the four wheat proteins were analyzed using TargetFreeze, a recently‐developed bioinformatics tool that predicts the likelihood of a protein to possess antifreeze activity.24 This would be suggested if the score obtained is higher than the threshold of 0.66. Values of 0.115 and 0.017 were obtained for TaBAS1 (BAA19099.1) and TaENO (AGH20061.1), respectively, indicating that these two proteins are not predicted to affect ice formation. As anticipated, TaIRI‐2 (AAX81543.1) showed the highest score at 0.840, supporting its antifreeze potential. A slightly below threshold score of 0.643 was obtained for WCS120 (AAA34261.2), suggesting it could possess some antifreeze activity.

Consistent with the bioinformatics prediction, IRI assays confirmed that TaIRI‐2 is able to inhibit ice recrystallization. This was anticipated because a TaIRI‐2 homolog in wheat, TaIRI‐1, also inhibits the growth of ice crystals.19 In accordance, TaIRI‐2 (10 mg/1.5 × 106 cells) provided high post‐thaw viability (85%) in INS832/13 cells. Intriguingly, the 20 mg/1.5 × 106 cells concentration that was efficient for antifreeze activity did not provide good cryoprotection in hepatocytes (39% viability). These results support our observations that cryoprotection mechanisms vary from cell type to cell type. The 43 kDa TaIRI‐2 protein possesses a signal peptide that likely targets the protein to the extracellular space or to the membrane in plants. The mature protein is predicted to have a molecular mass of 40.7 kDa, and has a unique bipartite structure that is not found in other antifreeze proteins. The N‐terminal portion is homologous to leucine‐rich repeat regions present in the receptor domain of receptor‐like protein kinases, and the C‐terminus is homologous to the ice‐binding domain (RI, recrystallization inhibition) of some antifreeze proteins. This RI domain is found in other plant IRI proteins such as the perennial ryegrass LpAFP and the Antarctic hairgrass Deschampsia antarctica.25, 26 TaIRI‐2 possesses six repeats of the xxNxVxG (‘a’ side) and xxNxVx—G (‘b’ side) motifs pair, which were suggested to form active ice‐binding sites.27 The protein's conformation conferred by these motifs is likely responsible for the high IRI activity of TaIRIs. Moreover, the fact that TaIRI recombinant proteins produced in a prokaryotic system (E. coli) show IRI activity supports the finding that protein glycosylation does not play a role in the protein's interaction with ice.28 Intriguingly, some AFPs like the carrot DcAFP possess antifreeze activity but do not have a–b motifs pairs forming an RI domain.29, 30, 31 It is likely that the cryoprotective function of TaIRI‐2 occurs via an interaction with water molecules or ice crystals, or by interactions with membrane proteins or phospholipids.

This study shows that TaBAS1 provides only modest IRI activity, despite its excellent cryoprotective properties in hepatocytes and INS cells. This indicates that the cryoprotective efficiency of TaBAS1 depends on properties other than IRI activity. The 23 kDa TaBAS1 protein possesses conserved motifs and residues that form the thioredoxin reductase domain, and is therefore predicted to function as a 2‐Cys peroxiredoxin (Prx). In plants, BAS1 genes are upregulated by abiotic stresses, which often involve an associated oxidative stress.32 Prxs are abundant in chloroplasts and mitochondria, where their role is likely to prevent oxidative damage that could arise from the high redox activity generated by photosynthesis and respiration.33 In addition to their peroxidase antioxidant function, Prxs display other functions as chaperones (holdase),21 thiol oxidases, redox sensors and modulators of signaling pathways upon oxidation.34, 35, 36 The chaperone activity is of particular interest in cryopreservation since the freeze/thaw process leads to protein denaturation following the increase in solute concentrations (due to ice formation), and changes in pH and protein hydration.37

The 39 kDa WCS120 protein is highly hydrophilic, a characteristic often found in freezing tolerance‐associated proteins.38 Because there exists a strong correlation between the level of WCS120 expression and the capacity of wheat genotypes to develop freezing tolerance,18 WCS120 was expected to be a good cryoprotective agent. However, our data show that WCS120 (up to 18 mg/mL) does not possess IRI activity and is not efficient for cryoprotection of hepatocytes or INS832/13 cells. These observations support those obtained for DHN5, the WCS120 ortholog in barley, which did not show IRI or TH activity.39 The fact that a combination of WCS120 and TaIRI‐2 proteins provides high cryoprotection for hepatocytes compared to either protein used alone,14 and the fact WCS120 does not possess antifreeze activity (this study), indicate that the cryoprotection conferred by WCS120 depends on biochemical properties that remain to be determined.

Enolase is a 48 kDa glycolytic enzyme whose most‐characterized function is to catalyse the conversion of 2‐phosphoglycerate to phosphoenolpyruvate.40 In addition, enolase possesses several unrelated and less‐characterized functions.40, 41 It is localized at the plasma membrane of several cell types, where it appears to act as a plasminogen receptor and trigger plasmin‐dependent signaling pathways. TaENO can protect cells against oxidative and nitrosative stress incurred during cryopreservation.20 Interestingly, glycolytic activity is not involved in the cryoprotective property of TaENO. The fact that enolase can be found inside cells after thawing suggests that it could act either at the intracellular or extracellular level. Possible functions include acting as a target of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species generated during cryopreservation, thus preventing damage to more important molecules or structures. Another possibility is a role in the stabilization of membrane proteins or phospholipids.42 The most puzzling result from the present study is that TaENO shows high IRI activity. The microscopy images clearly show that TaENO causes a notable decrease in the size of ice crystals, despite the fact that no antifreeze activity was predicted from analysis of the amino acid sequence using the AFP predictor TargetFreeze.24 Even though TargetFreeze analyses multiple protein features, it appears that nontypical antifreeze domains remain to be identified and included in the algorithms used for AFP prediction.

There appear to be multiple cell type‐dependent factors that contribute to cryodamage in cells. These factors include rates of temperature change (cooling and warming), increases in the concentrations of solutes (e.g., salt) that are dissolved in the remaining liquid phase due to the freezing of water, and the recrystallization of ice.8, 9 Ice recrystallization can occur at both the intracellular and extracellular levels. There is strong evidence that the growth of intracellular ice crystals leads to cell death. Faster cooling rates of cells (e.g., 10°C/min.) lead to increased intracellular ice formation compared to slower cooling rates of 1°C/min. At slower cooling rates, the cytoplasm is kept at its freezing point because water quickly moves out of the cells, which prevents intracellular ice formation.9 It has been suggested that under these conditions, freeze‐induced damage would be less a question of ice formation than of the higher solutes concentration resulting from cellular dehydration.8 Intracellular ice formation is unlikely at slower cooling rates such as 1°C/min combined with rapid warming, which were the conditions used in our cryopreservation procedure. However, this slow cooling rate would not prevent the formation of extracellular ice. Although the question is not entirely resolved, it appears that extracellular ice can be damaging to cells during cryopreservation.8, 43 It would therefore be critical to avoid both intracellular and extracellular recrystallization of ice to achieve efficient cryopreservation of living cells, tissues and organs.8 Another question arising from this work is to determine the relative cryoprotective potency of the four proteins. Data were thus analyzed using the units described here (mg/1.5 × 106 cells) and using calculated mM concentrations. Attempts to establish clear links between the two cell types, between each protein, and between the effective concentrations for post‐thaw viability and for IRI proved unsuccessful. Likewise, beyond determining the protein concentration needed to achieve similar or higher cell protection, it is difficult to compare the potencies of the different wheat proteins with that of DMSO. Nevertheless, because of their high IRI activity, the wheat recombinant proteins TaIRI‐2 and TaENO are promising candidates to reduce the growth of ice crystals. They could therefore prove useful to improve cryopreservation protocols for hepatocytes and insulin‐secreting cells, and possibly other cell types.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of wheat protein extracts and recombinant proteins

Winter wheat plants (Triticum aestivum L. cv Clair) were grown for 10 days and proteins were extracted as previously described.14 Partially purified wheat protein extracts (WPE) were prepared by acetone precipitation (55%), dialysis against 10 mM NaCl in ultrapure water and freeze drying.14 Protein integrity was validated and quantified by SDS‐PAGE.

Two wheat cDNAs (WCS120, TaIRI‐2)19, 38 were expressed from the pTrcHis vector in Escherichia coli, as previously described.16 Two other wheat cDNAs (TaENO and TaBAS1) were expressed from the pNew vector in E. coli, as previously described.20 His‐tagged proteins were purified on cobalt‐binding resin using a BioLogic Duo‐Flow system (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, ON).

Oregon green protein labeling and visualization

Purified proteins (4 mg/mL) were solubilized in PBS. Five hundred µl of purified protein (2 mg) and 50 µL of 1M bicarbonate were added to a vial of Oregon Green 488 reactive dye (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The labeled protein was then deposited on the purification resin and protein elution was followed by illumination with a UV lamp. The cells were first incubated with LysoTracker Red DND‐99 (50 nM) (Molecular Probes) in a µ‐dish (35 mm) for confocal microscopy, and then the fluorescently‐labeled protein was added to cells. A time course video was captured during 30 min. In parallel, LysoTracker Red and the fluorescent proteins were added to cells, which were subsequently subjected to our freeze‐thaw protocol (see below) prior to confocal microscopy analysis. As positive control for endocytosis, cells were incubated with pHrodo Green Dextran (50 µg/mL) and LysoTracker Red for 3 min.

IRI activity

Analysis for IRI activity was performed using the “splat cooling” method as previously described.44 The analyte was dissolved in PBS and a 10 μL droplet of this solution was dropped from a height of two meters from a micropipette on to a block of polished aluminum precooled to approximately −80°C. The droplet froze instantly on the polished aluminum block and was approximately 1 cm in diameter and 20 μm thick. This wafer was then carefully removed from the surface of the block and transferred to a cryostage held at −6.4°C for annealing. After a period of 30 min, the wafer was photographed between crossed polarizing filters using a digital camera (Nikon CoolPix 5000) fitted to the microscope. A total of three images were taken from each wafer. Image analysis of the ice wafers was performed using a novel domain recognition software (DRS)45 to generate the mean grain size (MGS) of ice crystals in the sample.

Thermal hysteresis

Nanoliter osmometry was performed using a Clifton nanoliter osmometer (Clifton Technical Physics, Hartford, NY), as described previously.46 All of the measurements were performed in doubly distilled water. Ice crystal morphology was observed through a Leitz compound microscope equipped with an Olympus 20× (infinity‐corrected) objective, a Leitz Periplan 32X photo eyepiece, and a Hitachi KPM2U CCD camera connected to a Toshiba MV13K1 TV/VCR system. Still images and videos were captured directly using a Nikon CoolPix digital camera.

Hepatocyte isolation and INS832/13 cell culture

Hepatocytes were isolated from male Sprague–Dawley rats (140–180 g) (Charles River Canada, Saint‐Constant, QC) by a two‐step collagenase digestion technique,47 and maintained as described.14 Animals were maintained and handled in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals. Cell viability, evaluated by FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) with 2 μM propidium iodide (PI),48 generally exceeded 80%.

Insulin‐secreting INS832/13 cells (passages 30–70) were grown in monolayer in tissue culture plates in RPMI‐1640 medium (pH 7.4) (Gibco/Life Technologies, Burlington, ON) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 10% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Wisent, Montreal QC), 2 mM l‐glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 µM β‐mercaptoethanol, and 50 µg/mL gentamycin («complete RPMI») at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.20, 49

Cell cryopreservation and viability

INS832/13 cells or hepatocytes (1.5 × 106) were added to 1 mL of ice‐cold complete RPMI without antibiotics or WME medium, respectively, and mixed with the WPE or recombinant wheat proteins (TaIRI‐2, TaBAS1, WCS120, TaENO) in cryovials.16 Cells cryopreserved with DMSO (15% + 50% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for hepatocytes; 10% + 50% FBS for INS cells) served as references. Cells were frozen at a cooling rate of 1°C/min in a freezing container (“Mr. Frosty”, Nalgene, Rochester NY) in a −80°C freezer for 24 h, and then transferred to liquid nitrogen for at least 7 days.20 Frozen cells were thawed quickly by gentle agitation in a 37°C water bath. Viability was determined by staining thawed cells with 9 μM SYTOX Green and/or 2 µM PI for 5 min. Cells (10,000) were analyzed by flow cytometry with the Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson).20

Previous studies indicated that efficiency of the wheat recombinant proteins for cryopreservation (viability) appears to depend more on the cell concentration than the volume used in the cryotubes.50 We therefore express the concentrations as mg protein per cell count (1.5 × 106 cells) instead of mg per ml solution. Moreover, previous data showed that about half the protein quantity used for hepatocytes was sufficient to provide similar cryoprotection to insulin‐secreting INS832/13 cells.20 This is likely due to the fact that INS832/13 cells are about half the size of hepatocytes.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between means of cell viability values obtained for the different treatments were performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by the Newman–Keuls post hoc test (P < 0.05 significance level). For IRI data, unpaired Student's t tests were performed to a 95% confidence level.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Emeritus Professor Fathey Sarhan (Université du Québec à Montréal) for helpful discussions and undergraduate students who helped to prepare plant protein extracts and recombinant proteins. MG, JGB and MCSY performed the experimental procedures and participated in data interpretation; DAB, RNB and FO designed the study and interpreted the data; DAB and FO wrote the manuscript. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hughes RD, Mitry RR, Dhawan A (2012) Current status of hepatocyte transplantation. Transplantation 93:342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stephenne X, Najimi M, Sokal EM (2010) Hepatocyte cryopreservation: is it time to change the strategy? World J Gastroenterol 16:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kabelitz D, Geissler EK, Soria B, Schroeder IS, Fandrich F, Chatenoud L (2008) Toward cell‐based therapy of type I diabetes. Trends Immunol 29:68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, Auchincloss H, Lindblad R, Robertson RP, Secchi A, Brendel MD, Berney T, Brennan DC, Cagliero E, Alejandro R, Ryan EA, DiMercurio B, Morel P, Polonsky KS, Reems JA, Bretzel RG, Bertuzzi F, Froud T, Kandaswamy R, Sutherland DE, Eisenbarth G, Segal M, Preiksaitis J, Korbutt GS, Barton FB, Viviano L, Seyfert‐Margolis V, Bluestone J, Lakey JR (2006) International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med 355:1318–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Brien PJ (2014) High‐content analysis in toxicology: screening substances for human toxicity potential, elucidating subcellular mechanisms and in vivo use as translational safety biomarkers. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 115:4–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Keeffe EB (2005) Acute liver failure. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 70:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khan SR, Baghdasarian A, Fahlman RP, Michail K, Siraki AG (2014) Current status and future prospects of toxicogenomics in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 19:562–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pegg DE (2010) The relevance of ice crystal formation for the cryopreservation of tissues and organs. Cryobiology 60:S36–S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mazur P (1984) Freezing of living cells: mechanisms and implications. Am J Physiol 247:C125–C142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davies PL (2014) Ice‐binding proteins: a remarkable diversity of structures for stopping and starting ice growth. Trends Biochem Sci 39:548–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Asghar W, El Assal R, Shafiee H, Anchan RM, Demirci U (2014) Preserving human cells for regenerative, reproductive, and transfusion medicine. Biotechnol J 9:895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeVries AL, Cheng CHC, Antifreeze proteins in polar fishes In: Farrell AP, Steffensen JF, Eds. (2005) Fish physiology. San Diego: Academic Press, pp 155–201. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ouellet F, Charron JB (2013) Cold acclimation and freezing tolerance in plants. Chichester, UK. DOI 10.1002/9780470015902.a0020093.pub2

- 14. Grondin M, Hamel F, Averill‐Bates DA, Sarhan F (2009) Wheat proteins improve cryopreservation of rat hepatocytes. Biotechnol Bioeng 103:582–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grondin M, Hamel F, Averill‐Bates DA, Sarhan F (2009) Wheat proteins enhance stability and function of adhesion molecules in cryopreserved hepatocytes. Cell Transplant 18:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grondin M, Hamel F, Sarhan F, Averill‐Bates DA (2008) Metabolic activity of cytochrome P450 isoforms in hepatocytes cryopreserved with wheat protein extract. Drug Metab Dispos 36:2121–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grondin M, Robinson I, Do Carmo S, Ali‐Benali MA, Ouellet F, Mounier C, Sarhan F, Averill‐Bates DA (2013) Cryopreservation of insulin‐secreting INS832/13 cells using a wheat protein formulation. Cryobiology 66:136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Houde M, Daniel C, Lachapelle M, Allard F, Laliberte S, Sarhan F (1995) Immunolocalization of freezing‐tolerance‐associated proteins in the cytoplasm and nucleoplasm of wheat crown tissues. Plant J 8:583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tremblay K, Ouellet F, Fournier J, Danyluk J, Sarhan F (2005) Molecular characterization and origin of novel bipartite cold‐regulated ice recrystallization inhibition proteins from cereals. Plant Cell Physiol 46:884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grondin M, Chow‐shi‐yee M, Ouellet F, Averill‐Bates DA (2015) Wheat enolase demonstrates potential as a non‐toxic cryopreservation agent for liver and pancreatic cells. Biotechnol J 10:801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chow‐shi‐yee M, Grondin M, Averill‐Bates DA, Ouellet F (2016) Plant protein 2‐Cys peroxiredoxin TaBAS1 alleviates oxidative and nitrosative stresses incurred during cryopreservation of mammalian cells. Biotechnol Bioeng Online. DOI: 10.1002/bit.25921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Storey KB, Storey JM (2013) Molecular biology of freezing tolerance. Comp Physiol 3:1283–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Antikainen M, Griffith M, Zhang J, Hon WC, Yang D, Pihakaski‐Maunsbach K (1996) Immunolocalization of antifreeze proteins in winter rye leaves, crowns, and roots by tissue printing. Plant Physiol 110:845–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. He X, Han K, Hu J, Yan H, Yang JY, Shen HB, Yu DJ (2015) TargetFreeze: Identifying antifreeze proteins via a combination of weights using sequence evolutionary information and pseudo amino acid composition. J Membr Biol 248:1005–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sidebottom C, Buckley S, Pudney P, Twigg S, Jarman C, Holt C, Telford J, McArthur A, Worrall D, Hubbard R, Lillford P (2000) Heat‐stable antifreeze protein from grass. Nature 406:256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. John UP, Polotnianka RM, Sivakumaran KA, Chew O, Mackin L, Kuiper MJ, Talbot JP, Nugent GD, Mautord J, Schrauf GE, Spangenberg GC (2009) Ice recrystallization inhibition proteins (IRIPs) and freeze tolerance in the cryophilic Antarctic hair grass Deschampsia antarctica E. Desv. Plant Cell Environ 32:336–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuiper MJ, Davies PL, Walker VK (2001) A theoretical model of a plant antifreeze protein from Lolium perenne . Biophys J 81:3560–3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pudney PD, Buckley SL, Sidebottom CM, Twigg SN, Sevilla MP, Holt CB, Roper D, Telford JH, McArthur AJ, Lillford PJ (2003) The physico‐chemical characterization of a boiling stable antifreeze protein from a perennial grass (Lolium perenne). Arch Biochem Biophys 410:238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Worrall D, Elias L, Ashford D, Smallwood M, Sidebottom C, Lillford P, Telford J, Holt C, Bowles D (1998) A carrot leucine‐rich‐repeat protein that inhibits ice recrystallization. Science 282:115–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meyer K, Keil M, Naldrett MJ (1999) A leucine‐rich repeat protein of carrot that exhibits antifreeze activity. FEBS Lett 447:171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smallwood M, Worrall D, Byass L, Elias L, Ashford D, Doucet CJ, Holt C, Telford J, Lillford P, Bowles DJ (1999) Isolation and characterization of a novel antifreeze protein from carrot (Daucus carota). Biochem J 340:385–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheng Z, Dong K, Ge P, Bian Y, Dong L, Deng X, Li X, Yan Y (2015) Identification of leaf proteins differentially accumulated between wheat cultivars distinct in their levels of drought tolerance. PLoS One 10:e0125302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baier M, Dietz KJ (1999) Protective function of chloroplast 2‐cysteine peroxiredoxin in photosynthesis. Evidence from transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 119:1407–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. König J, Muthuramalingam M, Dietz KJ (2012) Mechanisms and dynamics in the thiol/disulfide redox regulatory network: transmitters, sensors and targets. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15:261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Poynton RA, Hampton MB (2014) Peroxiredoxins as biomarkers of oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840:906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sevilla F, Camejo D, Ortiz‐Espin A, Calderon A, Lazaro JJ, Jimenez A (2015) The thioredoxin/peroxiredoxin/sulfiredoxin system: current overview on its redox function in plants and regulation by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. J Exp Bot 66:2945–2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pikal‐Cleland KA, Rodriguez‐Hornedo N, Amidon GL, Carpenter JF (2000) Protein denaturation during freezing and thawing in phosphate buffer systems: monomeric and tetrameric beta‐galactosidase. Arch Biochem Biophys 384:398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Houde M, Danyluk J, Laliberte JF, Rassart E, Dhindsa RS, Sarhan F (1992) Cloning, characterization, and expression of a cDNA encoding a 50‐kilodalton protein specifically induced by cold acclimation in wheat. Plant Physiol 99:1381–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hughes SL, Schart V, Malcolmson J, Hogarth KA, Martynowicz DM, Tralman‐Baker E, Patel SN, Graether SP (2013) The importance of size and disorder in the cryoprotective effects of dehydrins. Plant Physiol 163:1376–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Diaz‐Ramos A, Roig‐Borrellas A, Garcia‐Melero A, Lopez‐Alemany R (2012) alpha‐Enolase, a multifunctional protein: its role on pathophysiological situations. J Biomed Biotechnol. Article ID 156795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pancholi V (2001) Multifunctional alpha‐enolase: its role in diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 58:902–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kimelberg HK (1978) Influence of lipid phase transitions and cholesterol on protein–lipid interaction. Cryobiology 15:222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pegg DE (2007) Principles of cryopreservation. Methods Mol Biol 368:39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Knight CA, Hallett J, DeVries AL (1988) Solute effects on ice recrystallization: an assessment technique. Cryobiology 25:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jackman J, Noestheden M, Moffat D, Pezacki JP, Findlay S, Ben RN (2007) Assessing antifreeze activity of AFGP 8 using domain recognition software. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 354:340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chakrabartty A, Hew CL (1991) The effect of enhanced alpha‐helicity on the activity of a winter flounder antifreeze polypeptide. Eur J Biochem 202:1057–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guillemette J, Marion M, Denizeau F, Fournier M, Brousseau P (1993) Characterization of the in vitro hepatocyte model for toxicological evaluation: repeated growth stimulation and glutathione response. Biochem Cell Biol 71:7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reader S, Marion M, Denizeau F (1993) Flow cytometric analysis of the effects of tri‐n‐butyltin chloride on cytosolic free calcium and thiol levels in isolated rainbow trout hepatocytes. Toxicology 80:117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel‐Rieger R, Prentki M, Newgard CB (2000) Isolation of INS‐1‐derived cell lines with robust ATP‐sensitive K+ channel‐dependent and ‐independent glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 49:424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hamel F, Grondin M, Denizeau F, Averill‐Bates DA, Sarhan F (2006) Wheat extracts as an efficient cryoprotective agent for primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Biotechnol Bioeng 95:661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information