Abstract

Many cellular processes are driven by collective forces generated by a team consisting of multiple molecular motor proteins. One aspect that has received less attention is the detachment rate of molecular motors under mechanical force/load. While detachment rate of kinesin motors measured under backward force increases rapidly for forces beyond stall‐force; this scenario is just reversed for non‐yeast dynein motors where detachment rate from microtubule decreases, exhibiting a catch‐bond type behavior. It has been shown recently that yeast dynein responds anisotropically to applied load, i.e. detachment rates are different under forward and backward pulling. Here, we use computational modeling to show that these anisotropic detachment rates might help yeast dynein motors to improve their collective force generation in the absence of catch‐bond behavior. We further show that the travel distance of cargos would be longer if detachment rates are anisotropic. Our results suggest that anisotropic detachment rates could be an alternative strategy for motors to improve the transport properties and force production by the team.

Keywords: motor proteins, dynein, Monte‐Carlo simulation, computational modeling

Introduction

Molecular motors are specialized proteins that are used by cells for transport and force generation. Molecular motors kinesin and dynein move along microtubules (MTs) while myosin motors move along actin filaments.1 These molecular motors often work in a team.2 A team of cytoplasmic dynein motors generates larger forces required during a variety of processes ranging from transport of large vesicular cargos to displacing large objects during various important cellular processes such as cell division and cell growth.3 Cytoplasmic dynein motors have been purified from bovine, murine, yeast, chicken, and other sources for biophysical studies at the level of single molecule.4 The insights gained from single molecules studies have been helpful in understanding their team work when they function in a group for transport and force generation, using theoretical and computational modeling.5, 6 Here, we discuss a recent biophysical measurement of detachment kinetics of cytoplasmic dynein motors derived from yeast by Nicholas et al.,7 and its significance in the field of motor proteins using computational modeling. Several earlier models5, 8, 9, 10 in their simulations assume that both forward as well as backward loads increase the motor detachment rate from the MT tracks in a similar manner, most commonly taken to be exponential. To the best of our knowledge, motor detachment rates have not been probed for forward and backward loads for non‐yeast dynein motors so far. Here, we discuss a recent measurement of detachment rate of yeast dynein motors by Nicholas et al.7 under forward and backward loads and its importance.

Results and Discussion

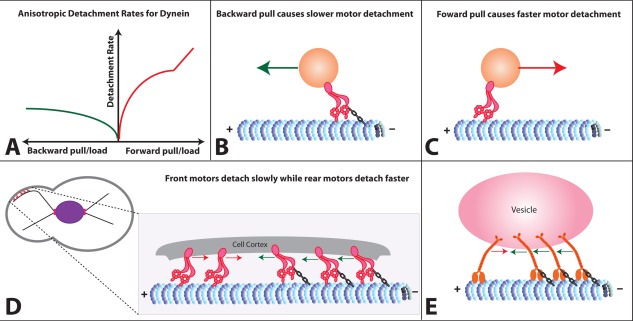

A recent interesting work by Nicholas et al.7 characterizes the MT binding strength of dynein monomers as a function of mechanical tension/load and nucleotide state. The authors have shown that yeast dynein responds anisotropically to applied mechanical tension [Fig. 1(A–C)]. Dynein detaches slowly from MT when pulled backward; detachment rate initially increases up to a load of ∼2 pN and almost saturates thereafter. However, for forward load, it increases more rapidly up to ∼6 pN and linearly thereafter. These results are remarkably different from the experimental reports of dynein catch‐bonding under higher backward pulling/load,3, 8, 11 as well as theoretical assumptions5, 6 that dynein's detachment rates are isotropic, i.e. identical under both forward and backward loads.

Figure 1.

A: Detachment rate of yeast dynein measured under forward and backward pull (load). B: Dynein head detaches slowly from MT under backward pull, this strong MT binding is illustrated using a chain between dynein head and MT. The direction of the backward pull/load is shown using a green arrow. C: Dynein head detaches faster from MT under forward pull whose direction is shown using a red arrow. D: A team of dynein motors is used to re‐position/displace larger objects such as nucleus in yeast.3 For strong pulling, it is desired that front motors which are experiencing a backward pull do not detach faster, while the ones which are experiencing a forward pull detach faster. E: Vesicular cargos can be hauled to longer distances if detachment rates of the motors under backward load are smaller than the detachment rates under forward load.

While these new experimental results that detachment rates are anisotropic for yeast dynein are interesting, it is not very surprising that yeast dynein motors have this biophysical property that is different from non‐yeast dyneins. It is known that yeast dynein, unlike other non‐yeast dyneins, is not used in vesicular transport, but it is used for displacing/re‐positioning large objects such as nuclei3 [Fig. 1(D)]. Further, experimentally measured biophysical properties of yeast dynein are altogether different from other non‐yeast dyneins, such as higher stall force and lower velocity.12, 13 Thus, it is already well‐known that many biophysical properties of yeast dynein are different from non‐yeast dyneins.

We propose that this novel anisotropic detachment property of yeast dynein becomes extremely important when dynein motors function as a team to exert forces required to displace large objects [Fig. 1(D)]. In this scenario, front motors experience a backward pull while rear motors might feel a forward pull due to tension. For a stronger forward pulling by this team, it is desired that front motors do not detach faster; while rear motors detach faster, so that forces produced by front and rear motors are not antagonistic.

To prove that such anisotropic detachment rates can help a team of motor proteins in generating larger forces in comparison to isotropic detachment rate, we extended the previously developed Stochastic Model of cargo transport5, 8, 9 for anisotropic and isotropic detachment rates. In the Stochastic Model, a cargo is driven by a maximum of N motors whose tails are attached to the cargo at a single spot. Motor proteins are modeled as special linkages of stiffness k, such that they exert a restoring force only when they are stretched beyond their rest length l; and they buckle without any resistance when compressed, similar to kinesin‐1 motors.5, 9, 14, 15 In Stochastic Model, the amount of load shared by a motor is determined by the relative position of that motor with respect to cargo, and motor stiffness. Thus, an external force F applied to a cargo, which is being driven by n bound/engaged motors out of total N motors available on the cargo, is shared stochastically among n engaged motors. Simulations start with all motors attached to the microtubule. At each time step, the engaged motors can step on microtubule with a force dependent stepping rate determined from force–velocity relation, or can detach from microtubule with a force dependent detachment rate, or can remain stationary. Additionally, the detached/unbound motors on cargo can also reattach to microtubule with certain force–independent reattachment rate. The equilibrium position of the cargo at each time step is obtained by using force balance. The cargo continues to move until all motors detach from the microtubule.

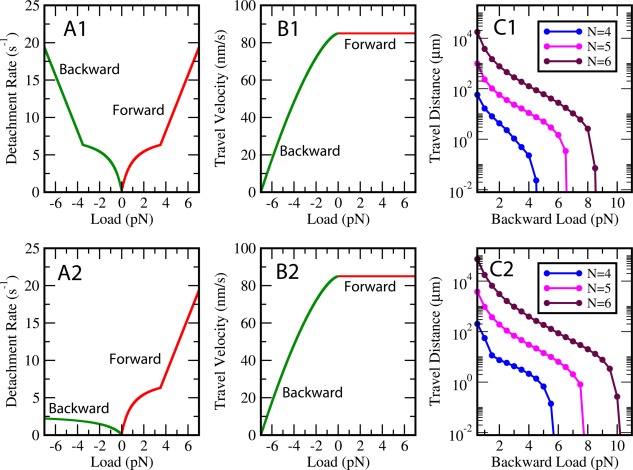

The travel distance of a cargo driven by a maximum of N motors under backward loads for isotropic and anisotropic detachment rates are given in Figure 2(C1,C2), respectively. The backward load at which travel distance becomes equal to 0.008 μm, i.e. 8 nm can be taken as a measure of the maximum force that can be produced by a team of N motors5 (since beyond this force a team of motors cannot move more than single motor step size). A comparison of forces for same N at which travel distance of the cargo becomes 8 nm clearly shows that maximum force produced by a team of N motors will be larger if detachment rates are anisotropic [compare Fig. 2(C2) with Fig. 2(C1)]. We, therefore, hypothesize that this anisotropy could be an evolutionarily‐tuned strategy of yeast dynein motors to produce large forces in the absence of catch‐bond behavior as reported for non‐yeast dynein motors.3, 8, 11

Figure 2.

A1: Isotropic detachment rate and (B1) force–velocity relation used in Stochastic Model to predict (C1) travel distance of a cargo driven by a maximum of N motors under backward loads. A2: Anisotropic detachment rate and (B2) force–velocity relation used in Stochastic Model to predict (C2) travel distance of a cargo driven by a maximum of N motors under backward loads. The origin of vertical axis has been chosen as 0.008 μm, i.e. 8 nm. The backward load at which travel distance becomes equal to 8 nm can be taken as a measure of maximum force that can be produced by a team of N motors.5 An increase in travel distance of the cargo for same value of N can be seen when detachment rates become anisotropic. The total number of configurations and parameter values used in simulations are given in Materials and Methods section.

Many recent studies5, 8 suggest that cargo travel distance is determined by motor's detachment rate under load. Figure 2 also shows an increase in travel distance of the cargo for all N when detachment rates become anisotropic [compare values of travel distance for same N in Fig. 2(C2) with Fig. 2(C1)]. If detachment rate of motors under forward load is higher than that under backward load, then rear motors would antagonize minimally with front motors, resulting in longer travel distances [Fig. 1(E)]. The travel distance of a team of yeast dynein motors becoming larger than 100 μm in small load regime does not have a direct physiological relevance for yeast cells as they are not involved in intra‐cellular transport. However, this is an indicative of the impressively large travel distances that can be achieved by a team of molecular motors whose biophysical properties are similar to yeast dynein motors. Since the detachment rates of most motors involved in vesicular transport have not been measured precisely, anisotropy in detachment rates might be discovered in future for some other motor proteins too.

To summarize, here we discussed a recent biophysical measurement of detachment kinetics of cytoplasmic dynein motors derived from yeast. We discussed the significance of observed anisotropy in detachment rates for forward and backward load using computational modeling. The anistropic detachment rates can help a team of motor proteins to increase their collective force production and travel distance. We hypothesize that such anisotropy could be an alternative strategy for yeast dynein motors to increase the collective force production in the absence of catch‐bond behavior. We further hypothesize that this alternative strategy can be also utilized by other types of motors for enhanced force production and longer travel distances. This, in turn, demands a careful investigation of detachment rates of various motor proteins involved in vesicular transport as well as force‐production.

Materials and Methods

In our Monte‐Carlo model, we do not model the two‐headed dynein motors explicitly. Each dynein motor is assumed to be single‐headed and is modeled as a linkage of rest length l. We further assume that detachment rate of single‐headed dynein, as measured by Nicholas et al.,7 is a fairly good estimate of collective detachment rate of a two‐headed motor, because only a single head of the two‐headed motor remains attached to the microtubule during its stepping.

In the Stochastic Model, N motor proteins are put on the cargo such that the motor tails are attached to the cargo via the linkages. Each linkage exerts a restoring force (according to Hooke's law) when attached to the microtubule and stretched beyond its rest length. The linkages have no compressional rigidity, i.e., they exert no force when compressed. Initially, cargo's center of mass was kept at the origin and all motors were allowed to attach to any discrete binding site on the track within distance l on either side of the cargo. Once all motors get attached to the microtubule, the initial position of the cargo's center of mass is determined using force balance, i.e., net force on the cargo is equal to zero.

In order to calculate travel distance, we simulated motion of multiple dynein driven cargo using Gillespie algorithm.16 Gillespie algorithm makes simulations faster by using two uniformly distributed random numbers—the first random number is used to determine when the next event would happen, and second random number is used to determine which event will happen out of all possible events. For a cargo instantaneously driven by n motors out of total N motors available on cargo, there are possible events, i.e., one of the n attached motors can step, or one of the n attached motors can detach, or one of the (N – n) detached motors can reattach.

During simulation, each of the N motors available on cargo is visited to determine their current states (attached or detached) and positions on the microtubule. After visiting each motor, we find out the instantaneous rates of events such as stepping, detachment, and reattachment associated with each motor. A currently detached motor can reattach with a force‐independent reattachment rate, to any binding site on the microtubule within distance l on either side of the cargo's center of mass. The reattachment rate was assumed to be 5/s.5, 17 The load felt by a currently attached motor was obtained by multiplying the extension of its linkage by the linkage stiffness k. In addition, for a currently attached motor there are two possible events—the attached motor can detach or step. The rates of these two events are determined by the current load on the motor which were calculated from single motor properties, i.e. detachment rates and force–velocity relation: (i) Rates of detachment were calculated from detachment rates of single motor for forward and backward loads, (ii) Rates of stepping were calculated using force–velocity relation of single dynein motor. The time of the next event depends on the sum of rates of all possible events. The probabilities of possible events are determined by dividing their corresponding rates by the sum of rates of all possible events.16

The force–velocity relation of dynein motors in the model was assumed to be super‐linear of the form for backward load,9, 17 with unloaded velocity v 0 = 85 nm/s and stall force F s = 7 pN.12, 13 The stepping rate was obtained by dividing the force velocity relation by the step size, i.e., 8 nm for backward loads less than stall force F s; for backward loads greater than F s stepping rate was taken to be zero as single motors stall for forces beyond F s. It was further assumed that motors move with unloaded velocity v 0 when pulled forward.5, 8 The unloaded travel distance of a single motor was assumed to be 1900 nm.13 The anisotropic detachment rates were obtained by fitting the experimental data by Nicholas et al.7 In the Stochastic Model with isotropic detachment rates, the detachment rate for backward load was assumed to be same as that for forward load. The rest length l of single dynein motors was taken as 60 nm and stiffness k was assumed to be 0.32 pN/nm as used in earlier models of transport by a team of dynein motors.6, 18 If the motor stepped, its position was incremented by its step size. Finally, the cargo position was updated using force balance.

The data for travel distance was obtained from 5000 configurations, where each configuration was started with the initial condition that all N are attached to the microtubule. In yeast, dynein motors work in a team consisting of several motors and therefore we started our simulations from N = 4 and above. Simulation for each configuration was stopped when all motors had detached from the microtubule. Error bars (S.E.M.) were calculated for each data point shown in Figure 2(C1,C2). Since error bars were smaller than symbol sizes used to plot these data points, they are not shown in Figure 2(C1,C2).

Supporting information

Supporting Information.

References

- 1. Mallik R, Gross SP (2006) Molecular motors as cargo transporters in the cell “The good, the bad and the ugly”. Phys A 372:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gross SP, Vershinin M, Shubeita GT (2007) Cargo transport: two motors are sometimes better than one. Curr Biol 17:R478–R486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mallik R, Rai AK, Barak P, Rai A, Kunwar A (2013) Teamwork in microtubule motors. Trends Cell Biol 23:575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xu J, Gross SP, Biophysics of dynein in vivo In: King SM, Ed. (2011) Dyneins: structure, biology and disease, London: Elsevier, pp190–206. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kunwar A, Vershinin M, Xu J, Gross SP (2008) Stepping, strain gating, and an unexpected force‐velocity curve for multiple‐motor‐based transport. Curr Biol 18:1173–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McKenney RJ, Vershinin M, Kunwar A, Vallee RB, Gross SP (2010) LIS1 and NudE induce a persistent dynein force‐producing state. Cell 141:304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nicholas MP, Berger F, Rao L, Brenner S, Cho C, Gennerich A (2015) Cytoplasmic dynein regulates its attachment to microtubules via nucleotide state‐switched mechanosensing at multiple AAA domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:6371–6376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kunwar A, Tripathy SK, Xu J, Mattson MK, Anand P, Sigua R, Vershinin M, McKenney RJ, Yu CC, Mogilner A, Gross SP (2011) Mechanical stochastic tug‐of‐war models cannot explain bidirectional lipid‐droplet transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:18960–18965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kunwar A, Mogilner A (2010) Robust transport by multiple motors with non‐linear force‐velocity relations and stochastic load sharing. Phys Biol 7:016012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mller MJ, Klumpp S, Lipowsky R (2008) Tug‐of‐war as a cooperative mechanism for bidirectional cargo transport by molecular motors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:4609–4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leidel C, Longoria RA, Gutierrez FM, Shubeita GT (2012) Measuring molecular motor forces in vivo: implications for tug‐of‐war models of bidirectional transport. Biophys J 103:492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gennerich A, Carter AP, Reck‐Peterson SL, Vale RD (2007) Force‐induced bidirectional stepping of cytoplasmic dynein. Cell;131:952–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reck‐Peterson SL, Yildiz A, Carter AP, Gennerich A, Zhang N, Vale RD (2006) Single‐molecule analysis of dynein processivity and stepping behavior. Cell 126:335–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shojania Feizabadi M, Janakaloti Narayanareddy BR, Vadpey O, Jun Y, Chapman D, Rosenfeld S, Gross SP (2015) Microtubule C‐terminal tails can change characteristics of motor force production. Traffic 16:1075–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu J, King SJ, Lapierre‐Landry M, Nemec B (2013) Interplay between velocity and travel distance of kinesin‐based transport in the presence of tau. Biophys J 105:L23–L25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gillespie DT (1977) Exact stochastic simulation of coupled chemical reactions. J Phys Chem 81:2340–2361. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rai AK, Rai A, Ramaiya AJ, Jha R, Mallik R (2013) Molecular adaptations allow dynein to generate large collective forces inside cells. Cell 152:172182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ori‐McKenney KM, Xu J, Gross SP, Vallee RB (2010) A cytoplasmic dynein tail mutation impairs motor processivity. Nat Cell Biol 12:1228–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information.