Abstract

Objective

To explore whether older adults with isolated hip fractures benefit from treatment in high-volume hospitals.

Design

Population-based observational study.

Setting

All acute hospitals in California, USA.

Participants

All individuals aged ≥65 that underwent an operation for an isolated hip fracture in California between 2007 and 2011. Patients transferred between hospitals were excluded.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Quality indicators (time to surgery) and patient outcomes (length of stay, in-hospital mortality, unplanned 30-day readmission, and selected complications).

Results

91 401 individuals satisfied the inclusion criteria. Time to operation and length of stay were significantly prolonged in low-volume hospitals, by 1.96 (95% CI 1.20 to 2.73) and 0.70 (0.38 to 1.03) days, respectively. However, there were no differences in clinical outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, 30-day re-admission, and rates of pneumonia, pressure ulcers, and venous thromboembolism.

Conclusions

These data suggest that there is no patient safety imperative to limit hip fracture care to high-volume hospitals.

Keywords: minimum volume standards, volume-outcome, hip fracture

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The California State Inpatient Database captures 98% of patient admissions to acute hospitals in a state of over 39 million people.

Unique patient and hospital identifiers permitted calculation of annual case volumes and tracking patient readmissions to any hospital in California.

This methodological approach adjusted for important patient-level and hospital-level characteristics but may be limited by residual confounding.

Introduction

There are approximately 250 000 hip fractures in the USA1 every year, which are a major cause of mortality and morbidity. High provider case volumes have been associated with improved outcomes across a range of surgical procedures, including major arterial vascular surgery,2 oesophageal resection,3 and elective arthroplasty.4 5 A small number of studies have explored the effect of hospital volume on hip fracture outcomes.6–11 However, these reports reached inconsistent conclusions, with only two identifying a relationship between hospital volume and outcomes.7 10 These studies predominantly used cross-sectional data sets that could not measure longitudinal outcomes such as readmission to hospital and complications following discharge.6 8 10 They also included cases from over 15 years ago7 that are unlikely to reflect modern hip fracture management. Contemporary hip fracture treatment emphasises the use of standardised clinical pathways,12 formal geriatric assessment13 and early operation to expedite mobility.14 It is possible that the increasing standardisation of hip fracture management will have influenced any relationship between clinical outcomes and provider volume.

A recent systematic review called for more studies aimed at characterising volume-outcome relationships for specific orthopaedic patient populations.15 This is necessary to determine the optimal setting for hip fracture patients and to inform both prehospital triage and interhospital referral pathways.

The aim of this study was to explore associations between case volume and outcomes using a comprehensive population database.

Methods

Data source

Hospital discharge records were analysed from the California State Inpatient Database (SID) 2007–2011. The SID is managed by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) which is an initiative of the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) intended for administrative and research purposes. It includes all inpatient discharge records from 98% of hospitals in California,16 regardless of payment source. Unique patient identifiers allow individuals to be tracked between admissions, so permitting longitudinal analysis of patient-level data. The SID was linked to the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey Database so that specific hospital characteristics (eg, trauma centre status) could be included within the analysis.

Study population

Patients with a primary or secondary International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code indicating ‘fracture of neck of femur’ (820.0–820.9) were extracted from the SID. Patients were excluded if they were aged <65 years, treated non-operatively, subject to an inter-hospital transfer, or had any other injury with an Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) severity score ≥2. Age 65 was chosen to exclude higher energy hip fractures in younger patients and because individuals aged ≥65 in the USA are universally insured through Medicare. Patients transferred between hospitals were excluded to minimise selection bias.

Patient and hospital characteristics

Extracted patient characteristics included age, sex, race (white, black, Hispanic, other), payment source (publicly funded, private insurance, self-pay) and weekend admission. AIS and Charlson comorbidity indices were generated using the ICDPIC and CHARLSON modules, respectively, in Stata Statistical Software Release V.13.0 (College Station, Texas, USA). The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) is a weighted score derived from 22 comorbid diagnoses. It is the most widely used comorbidity score for analysing administrative data sets17 and has been shown to predict resource utilisation18 and mortality19 in hip fracture populations.

Hospital characteristics included trauma centre level (1–4, with level 1 representing large regional trauma centres), teaching status (defined as hosting a physician training programme accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)), and hospital bed size (categorised as <200 and ≥200 beds).

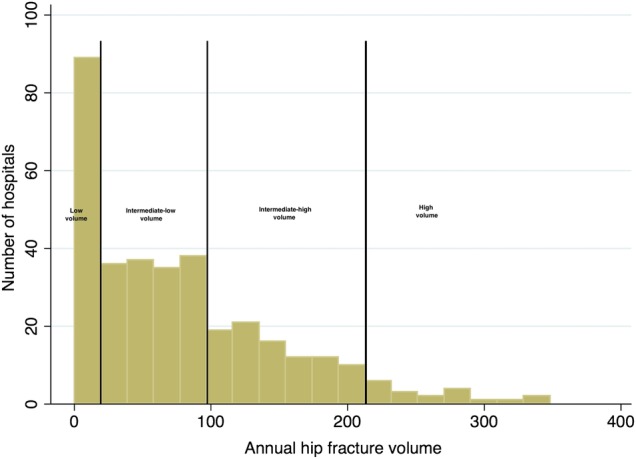

Unique identifiers within the SID were used to determine the annual hip fracture case volume of each hospital. Visual inspection of a histogram (number of hip fracture patients vs the annual volume at each treating hospital) revealed four distinct groups (figure 1). The four volume groups were defined as: low <20, intermediate-low 20–99, intermediate-high 100–215, and high >215 cases per year. Although data from all categories are reported, the principal comparison in this paper was between high and low-volume hospitals.

Figure 1.

A histogram showing the frequency of hospitals in California by annual hip fracture case volume and selected category thresholds.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures included length of stay (LOS), in-hospital mortality, unplanned readmission, and selected complications experienced as an inpatient or within 30 days postdischarge from the hospital. Both days to operation and LOS were measured from time of admission rather than time of injury, which is not available from the SID. Complications were identified by ICD-9-CM codes as venous thromboemboli (deep vein thrombosis 453.4, pulmonary embolus 415.1, pneumonias (480–488) and decubitus ulcers (707.0). These complications were also considered together as a single composite outcome. Only patients discharged alive from the hospital were eligible for calculating LOS and 30-day readmission. Readmissions and sequelae were captured even if the patient presented to a different (non-index) hospital in the state of California rather than the institution that treated their hip fracture.

Sensitivity analysis

As comparatively few patients (and associated adverse events) were anticipated in the low-volume category, a sensitivity analysis was planned with low and intermediate-low-volume categories combined before comparison with the two higher volume groups.

Statistical analysis

Outcome variables were compared between the volume categories using χ2 tests for categorical variables and Kruskall-Wallis one-way analysis of variance for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine the risk-adjusted associations of case volume with mortality, unplanned 30-day readmission, and postoperative complications. Covariates included in regression models were age, sex, race, payment source, weighted CCI (as a continuous covariate), discharge destination, hospital bed size, teaching status and trauma centre level. All models accounted for clustering of patients within hospitals and used robust SEs.

LOS presented as right-skewed data and so risk-adjusted associations were explored using generalised linear regression with a γ distribution20 and link log followed by postestimation of average marginal effects to attain predicted mean differences in LOS. The threshold for statistical significance was set at two-sided p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata V.13.0. The Partners Human Research Committee approved the study protocol (IRB 2014P002072/BWH).

Results

Patient and hospital characteristics

There were 91 401 patients in the final cohort, demographic and admission characteristics for which are shown in table 1. The mean age was 81.7 (SD 8.3) years. The patients were predominantly female (71.7%), white (81.0%), publicly insured (91.1%), admitted during the working week (72.6%), and had a CCI <2 (68.7%). A greater proportion of non-white and male patients were treated in lower volume hospitals. Patients were more commonly treated at a high-volume hospital if presenting during the weekend (27.4% vs 21.4%, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the final hip fracture cohort

| High volume | Intermediate-high volume | Intermediate-low volume | Low volume | Total cohort | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 16 992 | 47 513 | 26 079 | 817 | 91 401 | |

| Age | 82.1 (SD 8.2) | 81.9 (SD 8.2) | 81.2 (SD 8.4) | 78.9 (SD 8.8) | 81.7 (SD 8.3) | <0.001* |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 4764 (28.1%) | 13 251 (28.0%) | 7480 (28.9%) | 255 (32.6%) | 25 750 (28.3%) | 0.003† |

| Female | 12 172 (71.9%) | 34 092 (72.0%) | 18 415 (71.1%) | 527 (67.4%) | 65 206 (71.7%) | |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 14 784 (88.5%) | 38 284 (82.2%) | 18 674 (74.6%) | 426 (58.6%) | 72 168 (81.0%) | <0.001† |

| Black | 209 (1.3%) | 862 (1.9%) | 771 (3.1%) | 23 (3.2%) | 1865 (2.1%) | |

| Hispanic | 971 (5.8%) | 4452 (9.6%) | 2692 (11.8%) | 245 (33.7%) | 8630 (9.7%) | |

| Other | 736 (4.4%) | 2997 (6.4%) | 2626 (10.5%) | 33 (4.5%) | 6392 (7.2%) | |

| Payment source | ||||||

| Self-pay | 116 (0.7%) | 210 (0.4%) | 253 (0.6%) | 5 (0.6%) | 484 (0.5%) | <0.001† |

| Private | 1192 (7.0%) | 3678 (7.7%) | 1825 (7.0%) | 56 (6.9%) | 6761 (7.4%) | |

| Public | 15 583 (91.7%) | 43 168 (90.9%) | 23 730 (91.0%) | 731 (89.5%) | 83 212 (91.1%) | |

| Other | 101 (0.6%) | 451 (1.0%) | 361 (1.4%) | 25 (3.1%) | 938 (1.0%) | |

| Weekend admission | ||||||

| Yes | 4654 (27.4%) | 13 158 (27.7%) | 7039 (27.0%) | 175 (21.4%) | 25 026 (27.4%) | <0.001† |

| No | 12 338 (72.6%) | 34 355 (72.3%) | 19 040 (73.0%) | 642 (78.6%) | 66 375 (72.6%) | |

| Charlson index | ||||||

| <2 | 11 767 (69.3%) | 32 455 (68.3%) | 18 007 (69.1%) | 589 (72.1%) | 62 818 (68.7%) | 0.009† |

| ≥2 | 5225 (30.8%) | 15 058 (31.7%) | 8072 (31.0%) | 228 (27.9%) | 28 583 (31.3%) | |

*Kruskall-Wallis one-way analysis of variance.

†χ2 test.

Within California, there were 257 individual hospitals that treated hip fractures, characteristics of which are described in table 2. They were predominantly teaching institutions (77.0%) without trauma centre designation (73.2%) and located in a non-rural setting (87.9%). The mean annual case volume was 79.1 (SD 72.6). However, this varied significantly between the categories: low 5.2 (SD 6.0), intermediate-low 59.0 (SD 22.6), intermediate-high 150.0 (SD 34.5), and high volume 276.0 (SD 37.5) cases per year (p<0.001). A higher proportion of low-volume hospitals were rurally situated (23.5% vs 0.0%, p<0.001) and maintained an accredited residency programme (79.4% vs 73.3%, p<0.001) but a lower proportion were designated as a trauma centre (26.8% vs 33.3%, p<0.001). Low-volume hospitals were also smaller in size, ranging from a mean of 109.3 beds in the low volume to 348.8 in the high volume category (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of hospitals treating patients in each volume category

| High volume | Intermediate-high volume | Intermediate-low volume | Low volume | Total cohort | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 15 | 82 | 126 | 34 | 257 | |

| Mean annual volume | 276 (SD 37.5) | 150 (SD 34.5) | 59 (SD 22.6) | 5.2 (SD 6.0) | 79.1 (SD 72.6) | <0.001* |

| Hospital bed size | 348.8 (SD 142.7) | 229.3 (SD 145.8) | 137.9 (SD 100.3) | 109.3 (SD 117.6) | 305.0 (SD 158.7) | <0.001* |

| Trauma centre† | ||||||

| Level 1 | 2 (12.5%) | 7 (8.4%) | 6 (4.5%) | 1 (0.3%) | 16 (6.0%) | |

| Level 2 | 3 (18.8%) | 21 (25.3%) | 10 (7.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 34 (12.8%) | |

| Level 3 | 1 (6.3%) | 3 (3.6%) | 13 (9.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 17 (6.4%) | |

| Level 4 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 4 (1.5%) | |

| Non-trauma centre | 10 (62.5%) | 52 (62.7%) | 100 (75.8%) | 32 (94.1%) | 194 (73.2%) | <0.001‡ |

| Rural setting | ||||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (6.1%) | 18 (14.3%) | 8 (23.5%) | 31 (12.1%) | |

| No | 15 (100.0%) | 77 (93.9%) | 108 (85.7%) | 26 (76.5%) | 226 (87.9%) | <0.001‡ |

| Teaching hospital | ||||||

| Yes | 11 (73.3%) | 57 (69.5%) | 103 (81.7%) | 27 (79.4%) | 198 (77.0%) | |

| No | 4 (26.7%) | 25 (30.5%) | 23 (18.3%) | 7 (20.6%) | 59 (23.0%) | <0.001‡ |

*Kruskall-Wallis one-way analysis of variance.

†Five institutions changed trauma centre designation between 2007 and 2012.

‡χ2 Test.

Clinical outcomes

The unadjusted outcomes are summarised in table 3 and results of the multivariable regression analyses in table 4.

Table 3.

Unadjusted hip fracture outcomes by hospital case volume

| High volume | Intermediate-high volume | Intermediate-low volume | Low volume | Total cohort | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median time to theatre (days) | 1.0 (IQR 0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | <0.001* |

| Median length of stay (days) | 4.0 (IQR 4.0–6.0) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | <0.001* |

| Discharge destination | ||||||

| Home | 749 (4.5%) | 2060 (4.4%) | 1610 (6.3%) | 99 (12.5%) | 4518 (5.1%) | |

| Short-term hospital | 38 (0.2%) | 186 (0.4%) | 239 (0.9%) | 10 (1.3%) | 473 (0.5%) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 14 431 (86.7%) | 39 992 (86.3%) | 21 255 (83.4%) | 617 (77.9%) | 76 295 (85.5%) | |

| Home healthcare | 1423 (8.6%) | 4089 (8.8%) | 2361 (9.3%) | 66 (8.3%) | 7939 (8.9%) | |

| Against medical advice | 7 (0.0%) | 21 (0.1%) | 22 (0.1%) | 22 (0.1%) | 7 (0.0%) | <0.001† |

| In-hospital mortality | 313 (1.8%) | 886 (1.9%) | 450 (1.7%) | 14 (1.7%) | 1663 (1.8%) | 0.585† |

| Unplanned readmission | 1987 (11.9%) | 4971 (10.7%) | 2829 (11.0%) | 101 (12.6%) | 9888 (11.0%) | <0.001† |

| Postoperative sequelae | ||||||

| All | 1650 (9.7%) | 5046 (10.6%) | 2727 (10.5%) | 90 (11.0%) | 9513 (10.4%) | <0.001† |

| VTE | 400 (2.6%) | 1262 (2.7%) | 515 (2.0%) | 17 (2.1%) | 2194 (2.4%) | <0.001† |

| Decubitus ulcers | 1029 (6.1%) | 3274 (6.9%) | 1874 (7.2%) | 60 (7.3%) | 6237 (6.8%) | <0.001† |

| Pneumonias | 320 (1.9%) | 951 (2.0%) | 575 (2.20%) | 20 (2.5%) | 1866 (2.0%) | <0.001† |

*Kruskall-Wallis one-way analysis of variance.

†χ2 Test.

VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Table 4.

Adjusted hip fracture outcomes by hospital case volume*

| Outcome | Category | Predicted mean difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Time to theatre* | High volume (reference) | – |

| Intermediate-high volume | 0.34 (0.05 to 0.62) | |

| Intermediate-low volume | 1.14 (0.80 to 1.48) | |

| Low volume | 1.96 (1.20 to 2.73) | |

| Length of stay* | High volume (reference) | – |

| Intermediate-high volume | 0.03 (−0.12 to 0.17) | |

| Intermediate-low volume | 0.32 (0.13 to 0.52) | |

| Low volume | 0.70 (0.38 to 1.03) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

| In-hospital mortality† | High volume (reference) | 1.00 |

| Intermediate-high volume | 1.02 (0.86 to 1.22) | |

| Intermediate-low volume | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.27) | |

| Low volume | 1.28 (0.74 to 2.22) | |

| Unplanned readmission† | High volume (reference) | 1.00 |

| Intermediate-high volume | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.98) | |

| Intermediate-low volume | 0.88 (0.73 to 1.05) | |

| Low volume | 1.06 (0.65 to 1.73) | |

| Post-operative sequelae† | High volume (reference) | 1.00 |

| Intermediate-high volume | 1.16 (0.95 to 1.41) | |

| Intermediate-low volume | 1.24 (0.99 to 1.55) | |

| Low volume | 1.45 (0.97 to 2.15) |

*Generalised linear regression model (output as predicted mean difference with 95% CIs).

†Multivariable logistic regression (output as adjusted ORs with 95% CIs).

Time to operation

The overall median time to the operating theatre was 1.0 days (IQR 0.0–2.00). In the unadjusted analysis, low-volume hospitals had a longer time to theatre (median 1, 90th centile 3 days) than high-volume hospitals (median 1, 90th centile 2 days) (p<0.001). Within a generalised linear regression model, adjusted surgical delay was inversely associated with hospital volume (p<0.001). This was a stepwise association with a higher predicted mean difference observed in each successive volume category relative to high-volume hospitals: intermediate-high 0.34 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.62), intermediate-low 1.14 (0.80 to 1.48), and low 1.96 (1.20 to 2.73). Patients in the lowest volume hospitals therefore reached the operating theatre almost 2 days later than those in the highest volume category (p<0.001).

Length of stay

Median LOS was 5.0 (IQR 4.0–6.0) days but this was inversely associated with case volume in unadjusted and adjusted analyses. In the multivariable regression model, there was no significant difference between the two highest volume categories. However, LOS in the intermediate-low volume and low-volume groups were 0.32 and 0.70 days longer respectively. A higher proportion of patients were discharged to another care facility from high-volume hospitals than from low-volume hospitals (86.9% vs 79.2%, p<0.001).

In-hospital mortality

There were 1663 in-hospital deaths in the cohort, with an overall mortality of 1.8%. There were no significant differences between volume categories in terms of in-hospital mortality, either in the unadjusted (p=0.585) or adjusted (p=0.380) analyses. The sensitivity analysis (high volume vs combined low and intermediate-low-volume hospitals) also did not detect any difference between the combined low volume and high-volume categories (p=0.964).

Thirty-day unplanned readmissions

A total of 9888 (11.0%) patients required unplanned readmission to hospital within 30 days of discharge. Rates of readmission varied between the groups with the highest rate observed in the low-volume category (12.6%, p=0.042). In the multivariable analysis, there was no consistent association between case volume and likelihood of readmission (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.73). This finding was confirmed by the sensitivity analysis with combined low-volume categories (OR 0.88, 0.74 to 1.05).

Hip fracture sequelae

Major hip fracture sequelae (venous thromboembolism (VTE), decubitus ulcers, and pneumonia) were reported in 9513 cases (10.4%). They occurred more commonly in the lowest volume category (11.0 vs 9.7%, p<0.001). However, this difference was not significant in the multivariable regression analysis (table 4).

There were 2194 patients with venous thromboembolism (2.4%), 6237 with decubitus ulcers (6.8%), and 1866 with pneumonia (2.0%). In the unadjusted analyses, decubitus ulcers and pneumonia occurred more commonly in low-volume hospitals while VTE occurred in high-volume hospitals (all p<0.001). However, there were no differences in either the primary adjusted (table 4) or sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

This study found evidence of less efficient hip fracture treatment (delayed operation and prolonged LOS) in low-volume hospitals. However, it did not identify any relationship between volume and clinical outcomes for patients with hip fractures. This is the first study to examine the relationship between hospital case volume and hip fracture outcomes using a contemporary population data set. Importantly, postdischarge complications could be identified if they required admission to any hospital in the state. Previous studies are dated or used cross-sectional databases that could not facilitate longitudinal follow-up of patients between institutions.6–11

In this study, the mean hip fracture case volume was 79.1 per year; with a relatively high number of low-volume (<20 per year) hospitals. Although the mean annual case volume in California was higher than previously described across the USA,7 21 hip fracture cases may be more concentrated in other settings. For example, in the UK, only six hospitals reported annual case volumes <100 in 2014.22

Although two previous studies have reported an inverse relationship between hospital volume and hip fracture mortality,7 10 no such finding emerged from this comprehensive population data set. This also conflicts with reports from other distinct surgical populations.2–5 One possibility is that hip fractures are commonly encountered during orthopaedic training23 and so surgeons should therefore be familiar with the needs of this patient group, even in low-volume centres. This might explain why hip fractures do not exhibit the volume-outcome relationship that has been identified for more specialised populations, for example, those undergoing revision arthroplasty surgery.4 5 Hip fracture treatment is also increasingly driven by protocols and pathways, which might reduce variation between hospitals.12 24

There was, however, evidence of higher quality care in high-volume centres. These include reduced delay to the operating theatre and LOS. One possible explanation for this finding is that staff expertise and clinical pathways improve with the experience that results from treating high numbers of similar patients. For example, pathways and processes might have been more developed at higher volume centres. It is important that, although LOS was shorter at high-volume centres, patients were more likely to be discharged to another healthcare facility than their own home. This suggests that relationships with other institutions (such as skilled nursing facilities) may contribute to achieving a shorter LOS. It is also a reminder that discharge from hospital does not necessarily represent the end of each patient journey.

An alternative explanation is proposed by the ‘selective referrals’ hypothesis, which claims that high-quality hospitals are referred a greater number of patients.9 This reverses the presumed direction of causation between volume and outcome. In this study, we controlled for some fixed hospital characteristics (eg, trauma centre status) but unknown hospital-level founding factors might have persisted. However, patients transferred between institutions were excluded to minimise the ‘selective referrals’ effect.

Although prolonged operation time has been associated with hip fracture sequelae (venous thromboembolism, pneumonia, and decubitus ulcers),25 these were not over-represented in the lower volume centres.

This study is not without limitations. As the SID is a retrospective data set, unknown confounding factors might have been omitted from our multivariable regression models. In particular, it was not possible to determine the role of individual surgeon case volume. Previous studies have suggested that surgeon volume may be even more important than hospital volume on patient outcomes. In one series of 173 508 elderly patients undergoing hip hemiarthroplasty for fracture, surgeons in the lowest volume category had an 18% increased mortality compared with those in the highest.10 It also is known that low-volume surgeons cluster in low-volume hospitals across a range of surgical procedures.26 27 However, we accounted for clustering of fixed hospital-level characteristics in the multivariable regression analysis, which should have controlled for such differences. Although we found no hospital-level effect, it is still possible that low-volume surgeons could have worse mortality outcomes, even in the absence of hospital-level differences. Although the California SID does not include the unique surgeon identifiers that would be necessary to calculate surgeon volume, this may be available in other data sets. For example, other SIDs include unique surgeon identifiers that could be used to explore interactions between surgeon and hospital volume. The California SID was selected for this study because its unique patient identifier variable permitted analysis of readmissions to all hospitals in the state. Further data sets may also be sought that can be linked to public death records so as to track deaths occurring outside of hospital. This is important because our study was unable to identify systematic differences in long-term outcomes (eg, 12-month survival) that might be more important to patients than 30-day readmission.

Conclusion

In light of these findings, there is no patient safety imperative to discourage low-volume hospitals from treating patients with hip fractures. However, our data did suggest that patients treated in low-volume hospitals are less likely to undergo prompt operation than those in high-volume institutions. Further work should attempt to determine whether volume could be associated with process differences, costs or long-term outcomes for older adults with hip fractures.

Footnotes

Contributors: DM conceived the study idea, undertook the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. OO, BG, CZ, MBH, DCP, AS and MLC contributed to the study design, interpretation of findings, and made critical revisions to the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Partners Healthcare Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Liporace FA, Egol KA, Tejwani N et al. What's new in hip fractures? Current concepts. Am J Orthop 2005;34:66–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Killeen SD, Andrews EJ, Redmond HP et al. Provider volume and outcomes for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, carotid endarterectomy, and lower extremity revascularization procedures. J Vasc Surg 2007;45:615–26. 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Cowan JA et al. Surgical volume and quality of care for esophageal resection: do high-volume hospitals have fewer complications? Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:337–41. 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04409-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravi B, Jenkinson R, Austin PC et al. Relation between surgeon volume and risk of complications after total hip arthroplasty: propensity score matched cohort study. BMJ 2014;348:g3284 10.1136/bmj.g3284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavernia CJ, Guzman JF. Relationship of surgical volume to short-term mortality, morbidity, and hospital charges in arthroplasty. J Arthoplasty 1995;10:133–40. 10.1016/S0883-5403(05)80119-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavernia CJ. Hemiarthroplasty in hip fracture care: effects of surgical volume on short-term outcome. J Arthroplasty 1998;13:774–8. 10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90029-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forte ML, Virnig BA, Swiontkowski MF et al. Ninety-day mortality after intertrochanteric hip fracture: does provider volume matter? J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:799–806. 10.2106/JBJS.H.01204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browne JA, Pietrobon R, Olson SA. Hip fracture outcomes: does surgeon or hospital volume really matter? J Trauma 2009;66:809–14. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31816166bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton BH, Ho V. Does practice make perfect? Examining the relationship between hospital surgical volume and outcomes for hip fracture patients in Quebec. Med Care 1998;36:892–903. 10.1097/00005650-199806000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah SN, Wainess RM, Karunakar MA. Hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture in the elderly surgeon and hospital volume-related outcomes. J Arthroplasty 2005;20:503–8. 10.1016/j.arth.2004.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sund R. Modeling the volume-effectiveness relationship in the case of hip fracture treatment in Finland. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:238 10.1186/1472-6963-10-238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgers PT, Van Lieshout EM, Verhelst J et al. Implementing a clinical pathway for hip fractures; effects on hospital length of stay and complication rates in five hundred and twenty six patients. Int Orthop 2014;38:1045–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grigoryan KV, Javedan H, Rudolph JL. Orthogeriatric care models and outcomes in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 2014;28:e49–55. 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182a5a045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung F, Lau TW, Kwan K et al. Does timing of surgery matter in fragility hip fractures? Osteoporos Int 2010;21 4):529–34. 10.1007/s00198-010-1391-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shervin N, Rubash HE, Katz JN. Orthopaedic procedure volume and patient outcomes: a systematic literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;457:35–41. 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180375514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacNeil A, Holman RC, Yorita KL et al. Evaluation of seasonal patterns of Kawasaki syndrome- and rotavirus-associated hospitalizations in California and New York, 2000–2005. BMC Pediatr 2009;9:65 10.1186/1471-2431-9-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharabiani MT, Aylin P, Bottle A. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for administrative data. Med Care 2012;50:1109–18. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825f64d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson DJ, Greenberg SE, Sathiyakumar V et al. Relationship between the Charlson Comorbidity Index and cost of treating hip fractures: implications for bundled payment. J Orthop Traumatol 2015;16:209–13. 10.1007/s10195-015-0337-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karres J, Heesakkers NA, Ultee JM et al. Predicting 30-day mortality following hip fracture surgery: evaluation of six risk prediction models. Injury 2015;46:371–7. 10.1016/j.injury.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faddy M, Graves N, Pettitt A. Modeling length of stay in hospital and other right skewed data: comparison of phase-type, gamma and log-normal distributions. Value Health 2009;12:309–14. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00421.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller BJ, Lu X, Cram P. The trends in treatment of femoral neck fractures in the Medicare population from 1991 to 2008. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:e132 10.2106/JBJS.L.01163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Royal College of Physicians. National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) Annual Report 2014. London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jameson SS, Lamb A, Wallace WA et al. Trauma experience in the UK and Ireland: analysis of orthopaedic training using the FHI eLogbook. Injury 2008;39:844–52. 10.1016/j.injury.2008.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su EP, Su SL. Femoral neck fractures: a changing paradigm. Bone Joint J 2014;96-B(Suppl A):43–7. 10.1302/0301-620X.96B11.34334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefaivre KA, Macadam SA, Davidson DJ et al. Length of stay, mortality, morbidity and delay to surgery in hip fractures. Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91-B:922–7. 10.1302/0301-620X.91B7.22446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang CM, Yin WY, Wei CK et al. The combined effects of hospital and surgeon volume on short-term survival after hepatic resection in a population-based study. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e86444 10.1371/journal.pone.0086444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harmon JW, Tang DG, Gordon TA et al. Hospital volume can serve as a surrogate for surgeon volume for achieving excellent outcomes in colorectal resection. Ann Surg 1999;230:404–11. 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]