Abstract

Objective

To investigate the epidemiology of road traffic injury (RTI) in Nepal for the period 2001–2013.

Methods

2 approaches, secondary data analysis and systematic literature review, were adopted. RTI data were retrieved from traffic police records and analysed for the incidence of RTI. Electronic databases were searched for published articles that described the epidemiology of RTI in Nepal.

Results

A total of 95 902 crashes, 100 499 injuries and 14 512 deaths were recorded by the traffic police over the 12-year period, 2001–2013. The mortality rate increased from 4/100 000 population in 2001–2002 to 7/100 000 population in 2011–2012. There were relatively more reported crashes yet fewer deaths in Kathmandu valley than the rest of the country. Of the 20 articles related to RTI, only 11 articles met the eligibility criteria, but these were mainly descriptive case series or cross-sectional hospital-based studies. The majority of RTI were reported to occur among motorcyclists and pedestrians, in males, and in the age group 20–40 years. The common sites of injury were lower and upper extremities. Only 3 articles mentioned possible causes of accidents that include pedestrian road behaviour, alcohol consumption and improper bus driving.

Conclusions

Nepal suffers a heavy burden of RTI, with higher fatalities on highways out of Kathmandu valley caused by bus crashes in hilly districts. The majority of published studies on RTI are descriptive and hospital based, indicating the need for more thorough investigation of causes of RTI and systematic recording of crashes for the development of effective interventions.

Keywords: ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, TRAUMA MANAGEMENT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study utilised secondary data analysis and systematic literature review to investigate the specific problems and available information with regard to road traffic injury (RTI) in Nepal, including the urban-rural divide in mortality, the nature of fatal crashes, the shortcomings of police records and the need to detail such investigations.

The secondary data were retrieved from national traffic police records to analyse crash incidence patterns in Kathmandu valley and elsewhere.

The systematic review searched electronic databases to identify and synthesise concepts underlying RTI.

The study strength included the incorporation of national data and published studies over a 12-year period, highlighting trends on incidence and documenting status of RTI.

The main limitation for the secondary data was the lack of details on RTI, especially the cause of crashes. None of the reviewed studies were aetiological with testimonies of drivers or other persons involved in the crashes.

Introduction

Globally, road traffic injury (RTI) is the eighth leading cause of death1 and is projected to rise to the top five by 2030.2 Approximately 90% of the estimated 1.2 million deaths from RTI occur in low-income and middle-income countries.3 In particular, countries in the Western Pacific Region and the South-East Asia Region of the WHO account for more than half of all RTI-related mortalities in the world. The mortality rate in the South-East Asia Region is 18.5/100 000 population and one-third of those deaths involve motorised 2–3 wheelers. About 30% of countries in this region have some policy to promote walking and cycling.3

In Nepal, the population has increased by 15% from 23.2 million in 2001 to 26.6 million in 2011,4 while the registration of vehicles jumped from 317 284 in the fiscal year 2000–2001 to 1 348 995 in 2011–2012, a rise of 325% in the same decade.5 There were almost 2 million vehicles registered throughout Nepal by July 2015. Approximately 80% of these vehicles are two wheelers (motorcycles), followed by light vehicles such as cars, jeeps and pickup vans.5

Similarly, there has been a dramatic increase in the national road network which is classified into two broad categories: strategic road network and local road network.6 The strategic road network comprises national highways and their feeder roads, which are constructed and maintained by the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, with more rapid increases in earthen road length (from 171 km in 2000 to 4173 km in 2012) than blacktop road length (from 2974 km in 2000 to 5573 km in 2012).7 The local road network is managed by the district authorities. These local roads were constructed to access rural villages in the hilly districts. It is estimated that the total length of the local road network in 2013 was 50 943 km, of which 34 766 km (68%) was earthen or gravelled.6

RTI is a common cause of injury and trauma in Nepal.8–10 According to a hospital-based study, among the 1848 patients with a history of trauma in eastern Nepal admitted within 1 year, 38%were due to RTI.11 Moreover, autopsy conducted in hospitals revealed that road accident was a major cause of death.12 13 There are multiple causes of road traffic crashes, mainly related to driving and drivers' behaviour, mechanical condition of the vehicle(s) involved, and the road environment.14 15 Before developing policy and appropriate interventions to curtail and prevent RTI, it is important to understand its epidemiology. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the incidence patterns of RTI in Nepal during the period 2001–2013.

Methods

This study of RTI in Nepal adopted two approaches: (1) secondary data analysis and (2) systematic literature review. In Nepal, road traffic accidents are recorded by the traffic police in each district, and complied for the whole country in the police headquarters in the Nepal capital, Kathmandu. Such raw data were retrieved for the period 2001–2013 for the secondary data analysis. The analysis consists of comparing RTI data between Kathmandu valley and the rest of the country, and producing mortality rates per population, per vehicle and per crash as per the census year. In Nepal, RTI refers to an injury or death event of a road user as a result of a traffic-related crash that involves at least one motor vehicle with two wheels.

For systematic review, electronic databases PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Google Scholar were searched for relevant articles describing epidemiology of RTI in Nepal. Key words used to identify the underlying concepts were: (1) injury (injur*/disab*/hospital/wound/morbid*/mortalit*/death/fatal), (2) road (road/traffic/accident/crash/collision) and (3) population (Nepal/Kathmandu). The literature search was initially conducted by combining the first two concepts in the title and abstract field using Boolean terms and word truncation. Later, the population referring to Nepal was added to the search. All articles extracted were then exported to EndNote for identification of relevant articles. The PRISMA checklist was adopted as the standard for the systematic review. Selected articles were those: (1) published between 1980 and 2014; (2) related to Nepal; (3) published in peer-reviewed journals and (4) described any epidemiological aspect of RTI based on primary data. Review articles were excluded. The full texts of the relevant articles were retrieved and results were finally presented in a tabular format.

Results

Incidence of RTI

Table 1 shows RTI statistics by place and time. There are 95 902 crashes, 100 499 injuries and 14 512 deaths in total over the 12-year period 2001–2013, with the average deaths per year being 1209 (SD 449). The road traffic-related mortality appeared to rapidly increase from 2007 onwards. Table 2 compares mortality rates per population, vehicles and crashes between the two population census years in Nepal. The mortality rate increased from 4/100 000 in 2001–2002 to 7/100 000 in 2011–2012. However, the corresponding deaths per vehicle and deaths per crash decreased over the same period, as shown in table 2.

Table 1.

Road traffic-related deaths and injuries in Nepal, 2001–2013

| Kathmandu valley |

Out of Kathmandu valley |

Total |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal year | Crashes (n) | Deaths (n) | Injuries (n) | Crashes (n) | Deaths (n) | Injuries (n) | Crashes (n) | Deaths (n) | Injuries (n) |

| 2001–2002 | 2180 | 75 | 1520 | 1643 | 804 | 3076 | 3823 | 879 | 4596 |

| 2002–2003 | 2225 | 180 | 2052 | 1639 | 502 | 3175 | 3864 | 682 | 5227 |

| 2003–2004 | 3652 | 86 | 2365 | 1778 | 716 | 3219 | 5430 | 802 | 5584 |

| 2004–2005 | 3709 | 127 | 2323 | 1823 | 681 | 3511 | 5532 | 808 | 5834 |

| 2005–2006 | 1989 | 83 | 2132 | 1905 | 742 | 3389 | 3894 | 825 | 5521 |

| 2006–2007 | 2097 | 93 | 2670 | 2449 | 860 | 5244 | 4546 | 953 | 7914 |

| 2007–2008 | 2211 | 120 | 2774 | 4610 | 1011 | 5134 | 6821 | 1131 | 7908 |

| 2008–2009 | 2765 | 137 | 3168 | 5588 | 1219 | 6898 | 8353 | 1356 | 10 066 |

| 2009–2010 | 4104 | 146 | 3864 | 7643 | 1588 | 7649 | 11 747 | 1734 | 11 513 |

| 2010–2011 | 4914 | 171 | 4185 | 9099 | 1518 | 8336 | 14 013 | 1689 | 12 521 |

| 2011–2012 | 5096 | 148 | 3713 | 9201 | 1689 | 8116 | 14 297 | 1837 | 11 829 |

| 2012–2013 | 4770 | 147 | 3677 | 8812 | 1669 | 8309 | 13 582 | 1816 | 11 986 |

| Total | 39 712 | 1513 | 34 443 | 56 190 | 12 999 | 66 056 | 95 902 | 14 512 | 100 499 |

Table 2.

Burden of road traffic injuries in Nepal

| Year | Population | Registered vehicles | Crashes | Deaths | Deaths/population | Deaths/vehicle | Deaths/crash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2002 | 23 151 423 | 317 284 | 3823 | 879 | 4/100 000 | 277/100 000 | 22.9/100 |

| 2011–2012 | 26 620 809 | 1 348 995 | 14 297 | 1837 | 7/100 000 | 136/100 000 | 12.84/100 |

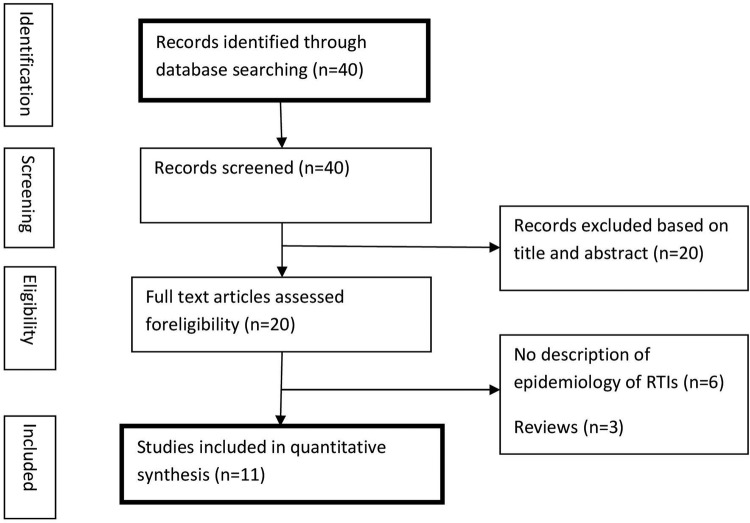

The RTI statistics in table 1 further indicate relatively higher reported crashes yet lesser deaths in Kathmandu valley than the rest of the country. Consequently, the mortality rate per crash in Kathmandu valley was relatively low when compared with elsewhere in Nepal. Figure 1 compares mortality rate per crash by place. The mortality rate per crash was fluctuating throughout the 12-year period 2001–2012, with a decreasing trend evident from 2007 onwards.

Figure 1.

Mortality rate per 100 crashes in Nepal and in Kathmandu valley, 2001–2012.

Studies on RTI in Nepal

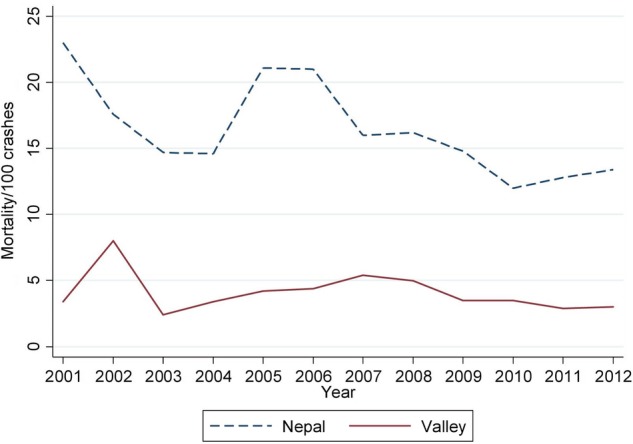

A search of the three concepts (injury, road, population) in the title and abstract field yielded 40 articles. These potential articles were then screened for relevancy. Twenty articles were found to be not related to RTI and were excluded. Of the remaining 20 articles assessed for eligibility, 3 were reviews and 6 studies did not describe epidemiology of RTI; see figure 2. Only 11 articles examined some epidemiological aspect and were subsequently included for our detailed review.13 15–24 Table 3 summarises these 11 articles, of which 8 were hospital-based studies with data derived from hospital cases. All articles were descriptive in nature: eight case series and three cross-sectional studies.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of studies selected for review (RTI, road traffic injury).

Table 3.

Studies related to epidemiology of road traffic injuries in Nepal

| Reference | Design | Setting | Sample size | Data collection | Aspects studied | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | Case series | Hospital based | 217 | Medical records | Pattern of injuries; characteristics of injured persons | Majority of injuries in motor cyclists followed by pedestrians injured persons were mainly males in the age group 16–30 years; most commonly affected parts were the head and face followed by lower limbs. |

| 17 | Case series | Hospital based | 757 | Medical records | Pattern of injuries; characteristics of injured persons | Pedestrians followed by motorcyclists commonly injured; lower limbs were mostly affected; mostly in the age group 21–40 years. |

| 18 | Case series | Hospital based | 615 | Medical records | Pattern of injuries; timing of accidents; characteristics of injured persons | Most injured were pedestrians in the age group 15–45 years, with lower extremities affected. |

| 19 | Prospective case series | Hospital based | 870 | Proforma-based interviews; medical records | Pattern of injuries; characteristics of injured persons; safety measures | Most affected were males in the age group 20–29 years, and they were pedestrians or passengers in the vehicles; 16.9% drivers consumed alcohol; seat belt not worn by car, jeep and van drivers. |

| 20 | Case series | Hospital based | 75 | Medico-legal autopsy; interview | Pattern of injuries | Fracture was the most common injury followed by laceration. |

| 15 | Cross-sectional | Community based | 365 deaths; 1751 injured persons | Police record and interviews | Characteristics and causes of bus accidents | Bus-only accidents were the most common followed by bus pedestrian and bus vehicle collisions; 75% of bus fatalities and injuries occurred during daylight hours; probable causes include drivers' habits, vehicle condition and road condition. |

| 21 | Case series | Hospital based | 360 | Proforma-based interviews | Characteristics of injured persons; causes of accidents | Most commonly affected were passengers and pedestrians in the age group 15–30 years; personal problems, alcohol consumption and old vehicles were identified. |

| 23 | Cross-sectional | School based | 1557 | Self-administered questionnaire | Causes of pedestrian injury | Road behaviours such as ‘looking both ways along the road before crossing’ or playing on the road or sidewalks are not significantly associated with pedestrian injury except for compliance with green signals. |

| 22 | Cross-sectional | School based | 1557 | Self-administered questionnaire | Types of vehicles; Activities of pedestrian | Injuries caused by motorcycles while crossing the road and walking in urban areas and in semi-urban areas. |

| 13 | Case series | Hospital based | 4383 autopsies | Medicolegal autopsy record | Characteristics of injured persons | About 18% of fatalities due to road traffic accidents; most common were pedestrians followed by occupants of public transport. |

| 24 | Case series | Hospital based | 80 | Medicolegal autopsy record | Characteristics of injured persons; intoxication status | 82% of fatalities due to road traffic accidents commonly involving pedestrians and motorcyclists; 34.8% were intoxicated among fatalities from road traffic deaths. |

The majority of articles described characteristics of the injured persons, types of vehicles involved and injury sites. Only three articles mentioned possible causes of accidents that include pedestrian road behaviour, alcohol consumption and improper bus driving.15 21 23 The common finding from these studies was that the majority of RTI occurred among motorcyclist and pedestrians, in males, and within the age group 20–40 years. The common sites of injury were lower and upper extremities.

Discussion

Nepal suffers a heavy burden of RTI. The number of road traffic fatalities per year is far more than those caused by natural disasters (eg, 614 deaths in 2009–2010)25 or by malaria (eg, 200 deaths in the 2006 epidemic).26 In fact, RTI ranks 11th among the leading causes of disability-adjusted life years and 12th among the leading causes of premature deaths in Nepal.27 The mortality rate per population due to RTI almost doubled from 2001 to 2013, suggesting that RTI is a silent epidemic in Nepal. The mortality rate of 7/100 000 population derived from police data in this study for 2011–2012 is lower than the WHO estimate of 17/100 000 population for the year 2013, which suggests that not all road deaths are captured by police data.

The rapid increase in deaths, especially from 2007 onwards, may be attributed to the overall increase in vehicles as well as road tracks, mostly earthen roads in hilly districts, which incur delay in accessing hospital emergency services in the event of a crash. On the other hand, the apparent reduction in mortality per vehicle or per crash merely reflects the dramatic increases in vehicle registration and associated number of non-fatal crashes.

In Nepal, the death tolls due to road traffic crashes mainly occur on highways and district roads out of Kathmandu valley or other major cities. The majority of such crashes concern bus passengers in hilly districts. The most common form of crashes involves bus-only, where the bus goes off the road in hilly terraces.15 Owing to the hilly and rocky terrain, the chance of occupant survival is low. Therefore, it is important to ensure maintenance of district village roads for the safe operation of local buses.

The nature of bus-only crashes also indicates driving-related issues as probable causes. Such issues include high speed, overtaking, overload, overwork and use of alcohol. Indeed, traffic crash data suggested driving-related issues are far more relevant than mechanical fault or pedestrian negligence.6 Alcohol drinking and motorcycle riding were strongly associated with the risk of experiencing an RTI in Vietnam.28 Travel in open-back utility vehicles, overcrowding and alcohol consumption were the main factors for RTI in Pacific Island countries.29 Surveillance by traffic police should be increased to enforce compliance of traffic laws and regulations. Since most of the accidents are related to drivers and driving behaviours, these aspects should be the key focus for any future intervention.

Apart from the traffic police data, the other sources of RTI data are derived from hospital medical records. Previous hospital-based studies found that persons in the age group 20–40 years, males, pedestrians and motorcyclists contribute to the majority of RTI, consistent with findings from China,30 India31 and Vietnam.28 This is somewhat expected considering the popularity of motorcycles among the age group 20–40 years. Drivers of vehicles are predominantly males in Nepal. Traffic education should be strengthened through public campaigning and safety promotion in schools targeting young novice motorcyclists.

Several limitations should be considered. Although none of the studies included in our review are aetiological, few have examined possible causes of crashes. The traffic police recorded data provide information on RTI in Nepal, but further analysis of the raw data is not feasible due to the restricted data access. Minor injuries or crashes without any dispute or property damage may not have been reported. However, fatal crashes are likely to be reported and captured by traffic police for legal actions. Currently, updated epidemiological data on road traffic crashes are lacking in Nepal. A thorough investigation on causes of RTI with detailed account of drivers and persons involved would provide useful insights for the prevention of RTI in Nepal.

Conclusion

Nepal suffers a heavy burden of RTI, with fatalities occurring mainly on highways caused by bus crashes in hilly districts out of Kathmandu valley. Traffic police data and hospital medical records provide the sources for RTI information. The majority of published studies on RTI in Nepal are descriptive and hospital based, suggesting that persons in the age group 20–40 years, males, pedestrians and motorcyclists are commonly injured. A thorough investigation of causes of crashes, especially bus-only crashes on highways, and systematic recording of road accidents are recommended for the development of effective intervention(s) to curtail and prevent RTI in Nepal.

Footnotes

Contributors: RK conceived the study design, performed analysis and drafted the manuscript. AHL assisted with data interpretation and revised the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: RTI data in Nepal are accessible on the traffic police website (http://traffic.nepalpolice.gov.np/) and in a document prepared by the department of roads (http://www.dor.gov.np/documents/Status_Paper%20_2013.pdf).

References

- 1.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R et al. . Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameratunga S, Hijar M, Norton R. Road-traffic injuries: confronting disparities to address a global-health problem. Lancet 2006;367:1533–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68654-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Global status report on road safety 2013. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Central Bureau of Statistics. National population and housing census 2011. Kathmandu: National Planning Commission Secretariat, Central Bureau of Statistics, Government of Nepal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.GoN. Vehicle registration record. Kathmandu: Nepal Government, Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thapa A. Status paper on road safety in Nepal. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.GoN. Road statistics data. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shrestha R, Shrestha SK, Kayastha SR et al. . A comparative study on epidemiology, spectrum and outcome analysis of physical trauma cases presenting to emergency department of Dhulikhel Hospital, Kathmandu University Hospital and its outreach centers in rural area. Kathmandu Univ Med J 2013;11:241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishra SR, Neupane D, Bhandari PM et al. . Burgeoning burden of non-communicable diseases in Nepal: a scoping review. Global Health 2015;11:32 10.1186/s12992-015-0119-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi SK, Shrestha S. A study of injuries and violence related articles in Nepal. J Nepal Med Assoc 2009;48:209–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajracharya A, Agrawal A, Yam B et al. . Spectrum of surgical trauma and associated head injuries at a university hospital in eastern Nepal. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2010;1:2–8. 10.4103/0976-3147.63092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subedi N, Yadav BN, Jha S et al. . A profile of abdominal and pelvic injuries in medico-legal autopsy. J Forensic Leg Med 2013;20:792–6. 10.1016/j.jflm.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma G, Shrestha PK, Wasti H et al. . A review of violent and traumatic deaths in Kathmandu, Nepal. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2006;13:197–9. 10.1080/17457300500373523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nantulya VM, Reich MR. The neglected epidemic: road traffic injuries in developing countries. BMJ 2002;324:1139–41. 10.1136/bmj.324.7346.1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maunder D, Pearce T. Bus accidents in the Kingdom of Nepal: attitudes and causes. Indian J Transport Manag 1998;22:123–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agnihotri AK, Joshi HS. Pattern of road traffic injuries: one year hospital-based study in Western Nepal. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2006;13:128–30. 10.1080/17457300500310236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banthia P, Koirala B, Rauniyar A et al. . An epidemiological study of road traffic accident cases attending emergency department of teaching hospital. J Nepal Med Assoc 2006;45:238–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dulal P, Khadka SB. Victims of road traffic crashes attending the emergency department of Kathmandu Medical College Teaching Hospital. Kathmandu Univ Med J 2004;2:301–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jha N, Agrawal CS. Epidemiological study of road traffic accident cases. A study from Eastern Nepal. Regional Health Forum, WHO South-East Asia Region, 2004:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandal BK, Yadav BN. Pattern and distribution of pedestrian injuries in fatal road traffic accidental cases in Dharan, Nepal. J Nat Sci Biol Med 2014;5:320–3. 10.4103/0976-9668.136175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishra B, Sinha ND, Sukhla S et al. . Epidemiological study of road traffic accident cases from Western Nepal. Indian J Community Med 2010;35:115 10.4103/0970-0218.62568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poudel-Tandukar K, Nakahara S, Ichikawa M et al. . Relationship between mechanisms and activities at the time of pedestrian injury and activity limitation among school adolescents in Kathmandu, Nepal. Accid Anal Prev 2006;38:1058–63. 10.1016/j.aap.2006.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poudel-Tandukar K, Nakahara S, Ichikawa M et al. . Unintentional injuries among school adolescents in Kathmandu, Nepal: a descriptive study. Public Health 2006;120:641–9. 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subedi N, Yadav BN, Jha S et al. . An autopsy study of liver injuries in a tertiary referral centre of eastern Nepal. J Clin Diagn Res 2013;7:1686–8. 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5913.3220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Central Bureau of Statistics. Nepal in figures. Kathmandu, Nepal: Government of Nepal, National Planning Commission, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.MoHP [Nepal]. Annual report of department of health services (2012/2013). Kathmandu: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Health and Population, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Health Matrics and Evaluation. GBD profile: Nepal. Washington: University of Washington, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le LC, Blum RW. Road traffic injury among young people in Vietnam: evidence from two rounds of national adolescent health surveys, 2004–2009. Glob Health Action 2013;6:1–9. 10.3402/gha.v6i0.18757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herman J, Ameratunga S, Jackson R. Burden of road traffic injuries and related risk factors in low and middle-income Pacific Island countries and territories: a systematic review of the scientific literature (TRIP 5). BMC Public Health 2012;12:479 10.1186/1471-2458-12-479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Xiang H, Jing R et al. . Road traffic injuries in the People's Republic of China, 1951–2008. Traffic Inj Prev 2011;12:614–20. 10.1080/15389588.2011.609925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsiao M, Malhotra A, Thakur JS et al. . Road traffic injury mortality and its mechanisms in India: nationally representative mortality survey of 1.1 million homes. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002621 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]