Abstract

Objective

To determine whether kidney transplants performed during a weekend had worse outcomes than those performed during weekdays.

Design

Retrospective national database study.

Setting

United Network for Organ Sharing database of the USA.

Participants

136 715 adult recipients of deceased donor single organ kidney transplants in the USA between 4/1994 and 9/2010.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcomes were patient survival and death-censored and overall allograft survival. Secondary outcomes included initial length of hospital stay after transplantation, delayed allograft function, acute rejection within the first year of transplant, and patient and allograft survival at 1 month and at 1 year after transplantation. Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the impact of weekend kidney transplant surgery on primary and secondary outcomes, adjusting for multiple covariates.

Results

Among the 136 715 kidney recipients, 72.5% underwent transplantation during a regular weekday (Monday–Friday) and 27.5% during a weekend (Saturday–Sunday). No significant association was noted between weekend transplant status and patient survival, death-censored allograft survival or overall allograft survival in the adjusted analyses (HR 1.01 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.04), 1.012 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.034), 1.012 (95% CI 0.984 to 1.04), respectively). In addition, no significant association was noted between weekend transplant status and the secondary outcomes of patient and graft survival at 1 month and 1 year, delayed allograft function or acute rejection within the first year. Results remained consistent across all definitions of weekend status.

Conclusions

The outcomes for deceased donor kidney transplantation in the USA are not affected by the day of surgery. The operationalisation of deceased donor kidney transplantation may provide a model for other surgeries or emergency procedures that occur over the weekend, and may help reduce length of hospital stay and improve outcomes.

Keywords: kidney transplantation, graft survival, patient survival, weekend effect

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first study to date investigating the ‘weekend effect’ of transplant surgery on kidney transplant outcomes.

Large-scale nationwide study using longitudinally captured long-term data in a robust and one of the largest transplant databases in the world.

Weaknesses inherent to retrospective study design and registry data: a potential for residual confounding from factors that are difficult to measure or bias associated with differences in ascertainment of outcomes.

The rate of postoperative complications by day of transplantation could not be analysed due to incompleteness of data.

The findings reflect transplantation practices in the setting of well-staffed tertiary centres in the USA and may not be generalisable to all geographic regions worldwide.

Introduction

Admissions to hospitals on weekends have been associated with increased morbidity and/or mortality compared with weekday admissions over the past few years, the so called ‘weekend-effect’. A number of studies have shown a significantly worse outcome among patients admitted in emergency on a weekend for various medical and surgical conditions that include myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, gastrointestinal haemorrhage, acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease, pulmonary embolism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, cervical trauma, and many other critical illnesses requiring admissions in the intensive care units.1–14 More recently, similar trends have been observed for elective surgeries and even in palliative care.14–16 Although the weekend effect may be a function of confounding by unmeasured differences in the severity of illness at the time of admission, others have hypothesised that differences in quality of care delivered between weekends and weekdays mediate this effect.1 2 10 11 During the weekend, the hospital staffing may be reduced and/or less experienced medical staff may be working. In addition, restricted availability of diagnostic or therapeutic procedures leading to delays in care may influence patient outcomes.

Organ transplantation from deceased donors (in contrast to live donors) is routinely performed as an emergency procedure, regardless of the time of the day or the day of the week, with timing of surgery largely driven by the timing of donor death. The single study examining the impact of weekend transplant surgery on outcome was in liver transplant recipients, and it showed a modest increase in 1-year allograft failure without any impact on 1-year patient survival.17 However, to the best of our knowledge, to date, no studies have investigated the impact of deceased donor kidney transplantation performed on weekends on patient or kidney allograft survival. In this study, we examined the association between day of kidney transplant surgery (weekend vs weekday) on both short-term and long-term patient and allograft survival utilising data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database of the USA. We hypothesised that kidney transplant surgery performed on weekends in the USA would have inferior outcomes compared to those performed during weekdays.

Methods

Study population

The UNOS includes extensive recipient-level and donor-level data on all transplants performed in the USA since 1 October 1987. The analysis used data extracted from the UNOS standard transplant analysis and research (STAR) files for transplants performed during the time period of 1 April 1994 through 3 September 2010. Data are collected and compiled by trained data entry personnel. Analyses were restricted to adults older than 18 years of age who underwent deceased donor kidney transplantation from 1 April 1994 to 10 September 2010. Recipients of live donor and multiorgan transplants were excluded. A total of 257 226 kidney transplants among recipients aged ≥18 years were recorded during the approximate 16-year time period. Of these 257 226 transplants, 231 976 underwent single organ kidney transplantation and 136 715 received kidney transplants from deceased donors. The study was approved by UNOS and the institutional review board of the Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, which waived the requirement for informed consent as this study used encrypted patient data.

Study design

The study design was a retrospective cohort study of transplant outcomes and overall survival among adults older than 18 years who underwent deceased donor kidney transplantation from 1 April 1994 through 3 September 2010.

Day of transplant surgery

The date of transplant surgery is collected by UNOS. Weekend surgery was defined as the date of surgery being a Saturday or Sunday and weekday surgery as the date of surgery being Monday to Friday. Sensitivity analyses examined differing definitions of weekend transplant status. For these analyses, we examined weekend transplant status being defined as either ‘Friday–Saturday’ or ‘Sunday–Monday’.

Outcomes and variables

The primary outcomes were patient survival and death-censored and overall allograft survival. Overall allograft survival was defined by death, return to dialysis or retransplantation, as per the standard UNOS ‘composite’ definition.18 Date of allograft failure was ascertained from the UNOS STAR files. Secondary outcomes included initial length of hospital stay after transplantation, delayed allograft function (defined as use of dialysis in the first week after transplantation), acute rejection (if treated for acute rejection, with or without a biopsy) within the first year of transplant and patient and allograft survival at 1 month and at 1 year after transplantation.

Potential confounding factors collected from the UNOS data included recipient age, gender, race, body mass index (BMI), time on waiting list, cause of end-stage renal disease (diabetes, hypertension, glomerulonephritis, cystic kidney disease or other) and prior kidney transplantation. Donor-related variables included donor age, sex and race/ethnicity, BMI, serum creatinine at the time of death, expanded criteria donor (ECD) status and donation after circulatory death (DCD) status. ECD was defined as the deceased donor who was older than 60 years, or between 50–59 years with any two of the following three criteria: (1) hypertension; (2) cerebrovascular cause of brain death; or (3) donor creatinine >1.5 mg/dL; and DCD donor was defined as the donor who did not meet the criteria for brain death but in whom cardiac standstill or cessation of cardiac function occurred before the organs were procured, as per the UNOS definitions.19 Transplant variables included peak panel reactive antibodies (PRA) before transplantation, degree of human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-mismatching, ABO incompatibility, cold ischaemia time, year of transplantation, and use of antibody induction and maintenance immunosuppressants.

Statistical analysis

We compared relevant characteristics by weekend transplant status using the χ2 test for categorical variables, the unpaired t test for continuous variables for data with normal distribution and the Mann-Whitney-U test for data with non-normal distribution. Patient and allograft survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and comparisons of survival rates by weekend transplant status were performed using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models were constructed to assess the association between weekend transplantation and primary and secondary outcomes while simultaneously adjusting for potential confounding factors. The covariates with a p value of less than 0.05 were then entered into a forward stepwise variable selection procedure and the variables selected by this procedure were then included in the final model. Variables with >10% of missing data were also excluded from the multivariate analysis. The only exception was the diagnosis of underlying renal disease that was included despite >10% missing data, due to its importance. Additionally, we analysed the impact of each day of the week separately on the outcome.

The results of the survival analysis are presented as HRs with 95% CIs and their associated p values. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean±SD or median and quartiles, as appropriate. Statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS software V.21. Two-tailed p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Among the 136 715 deceased donor kidney transplant procedures, 99 061 patients underwent transplantation during a regular weekday (Monday–Friday) and 37 654 (27.5%) during a weekend (Saturday–Sunday). The average age of the recipients was 49.6±13.2 years and 60.6% were males. The median follow-up time was 54.6 months. The baseline characteristics in the two groups stratified according to weekend transplantation status are presented in table 1. The two groups were similar with respect to most of the baseline characteristics except for small differences in the cold ischaemia time, the proportion of zero HLA mismatch transplants, ABO-incompatible transplants, donor gender, donor race and DCD donors.

Table 1.

Baseline donor and recipient characteristics stratified by weekday and weekend transplantation

| Weekday Tx (N=99 061) | Weekend Tx (N=37 654) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient characteristics | |||

| Age (mean±SD) | 49.6±13.2 | 49.6±13.2 | 0.71* |

| Gender (% males) | 60.6 | 60.6 | 0.87† |

| Race (%) | 0.16† | ||

| White | 52.0 | 52.3 | |

| Black | 30.4 | 30.5 | |

| Hispanic | 12.7 | 12.2 | |

| Other | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| BMI median (IQR) | 25.2 (22.0–29.2) | 25.1 (22.0–29.3) | 0.30‡ |

| Diagnosis of ESRD | 0.29† | ||

| Diabetes | 22.9 | 22.9 | |

| Hypertension | 24.3 | 24.4 | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 23.7 | 24.0 | |

| Cystic kidney disease | 8.8 | 8.9 | |

| Other | 18.5 | 18.0 | |

| Unknown | 1.8 | 1.8 | |

| Days on waiting list, median (IQR) | 559 (228–1069) | 565 (229–1067) | 0.28‡ |

| Peak level of PRA (%) median, (75, 90, 95 centiles) | 2 (16, 78, 93) | 1 (15, 77, 93) | 0.33‡ |

| Prior kidney Tx (%) | 10.6 | 10.3 | 0.119† |

| Cold ischaemia time in hours: median (IQR) | 19 (13–24) | 18 (13–24) | <0.001‡ |

| Zero HLA mismatch (%) | 14.2 | 13.5 | 0.002† |

| Number of HLA mismatches (mean±SD) | 3.5±1.9 | 3.5±1.8 | 0.056* |

| ABO-incompatible Tx | 5.1 | 4.7 | 0.027† |

| Year of transplantation (%) | 0.072§ | ||

| 1994 (April 1)-1995 (n=17 816) | 9.2 | 9.5 | |

| 1996–2000 (n=57, 880) | 27.3 | 27.7 | |

| 2001–2005 (n=71, 353) | 30.5 | 30.0 | |

| 2006–2010 (September 3) (n=72 615) | 32.9 | 32.8 | |

| Donor characteristics | |||

| Age (mean±SD) | 37.3±17.1 | 37.3±17.1 | 0.52* |

| Gender (% males) | 59.6 | 58.7 | 0.003† |

| BMI median (IQR) | 25.2 (22.0–29.2) | 25.1 (22.0–29.3) | 0.30‡ |

| Race | <0.001† | ||

| White | 73.9 | 74.0 | |

| Black | 11.8 | 12.4 | |

| Hispanic | 12.3 | 11.6 | |

| Other | 2.0 | 1.9 | |

| Expanded criteria donor % | 16.4 | 16.4 | 0.89† |

| Donor creatinine mg/dL (mean±SD) | 1.15±1.30 | 1.14±1.33 | 0.70† |

*t-test independent samples.

†χ2-test proportions.

‡Mann-Whitney test.

§χ2-trend test.

BMI, body mass index; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; PRA, panel reactive antibodies; Tx, transplant.

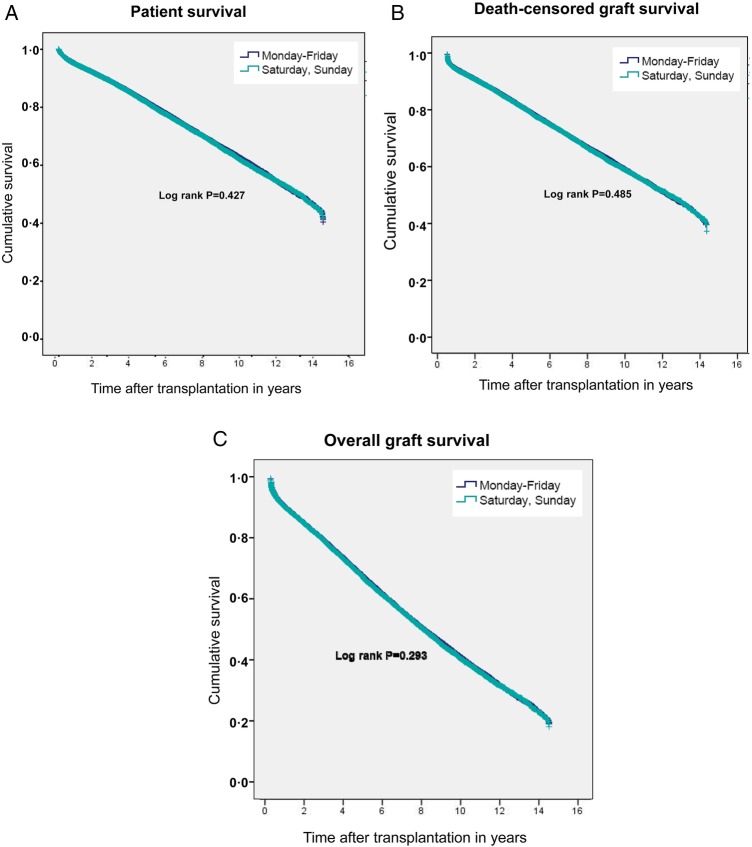

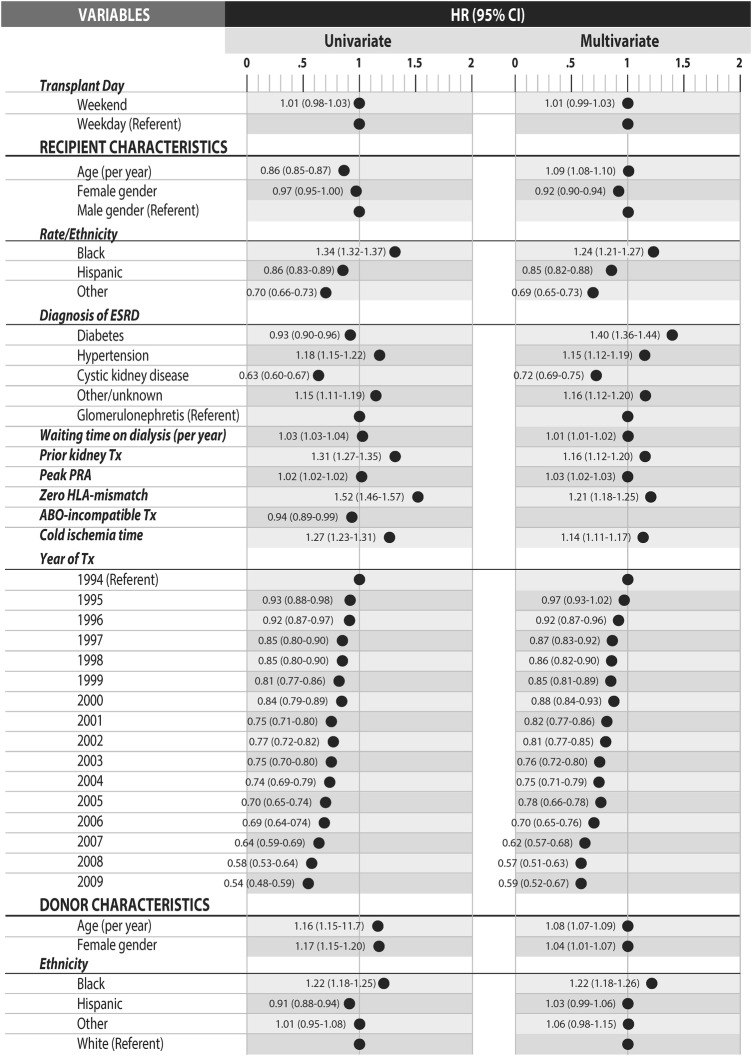

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patient survival (figure 1A), death-censored allograft survival (figure 1B) and overall allograft survival (figure 1C) by weekend status are shown in figure 1. Overall, patient survival, death-censored allograft survival and overall allograft survival appeared similar in the two groups (figure 1 and table 2). In unadjusted analyses, no significant association was noted between weekend transplantation status and patient survival (HR 1.01 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.04)), death-censored allograft survival (HR 1.01 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.03)) or overall allograft survival (HR 1.009 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.03)). The results of the Cox proportional hazards model for death-censored allograft survival are shown as a forest plot in figure 2. Results did not change with adjustment for potential confounding factors (table 2, online supplemental tables S1a,b). Weekend transplant status was also not significantly associated with patient or allograft survival (both death-censored and overall) at 1-month or 1-year following transplantation regardless of adjustment for confounding factors (data not shown). Furthermore, no significant association was noted between weekend transplant status and secondary outcomes including delayed allograft function or acute rejection within the first year of transplant (table 3). Median length of hospital stay was significantly lower (6.0 days (IQR 5–9) vs 7.0 days (IQR 5–10); p=0.008) with transplants performed over the weekend versus weekday.

Figure 1.

(A–C). Kaplan–Meier curves for patient survival, death-censored allograft survival and overall allograft survival, respectively.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and multivariable adjusted HR for allograft and patient survival by weekend transplant status

| Variable |

||

|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Weekday (95% CI) | Weekend (95% CI) |

| Median patient survival in years | 13.52 (13.29 to 13.74) | 13.65 (13.30 to 14.00) |

| HR | ||

| Univariate | 1.00 (referent) | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.04) |

| Multivariate | 1.00 (referent) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) |

| Median death-censored allograft survival in years | 12.73 (12.52 to 12.94) | 12.82 (12.50 to 13.14) |

| HR | ||

| Univariate | 1.00 (referent) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.03) |

| Multivariate | 1.00 (referent) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) |

| Median overall allograft survival (including death) in years | 8.28 (8.18 to 8.37) | 8.24 (8.10 to 8.38) |

| HR | ||

| Univariate | 1.00 (referent) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) |

| Multivariate | 1.00 (referent) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) |

Figure 2.

Forest plot demonstrating the results of the Cox proportional hazards model for death-censored allograft survival. Reference category for the ethnicity was white race; for the diagnosis of ESRD, it was glomerulonephritis, and for the year of Tx it was 1994. HR of PRA refers to an increase of 10. The year 2010 was excluded from the analysis because of the short observation period. ESRD, end-stage renal disease; Tx, transplant; PRA, panel reactive antibodies; HLA, human leucocyte antigen.

Table 3.

Effect of weekend transplant status on secondary outcomes

| Weekday Tx (N=99 061) | Weekend Tx (N=37 654) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delayed allograft function (use of dialysis within first week) % | 24.9% | 24.6% | 0.7* |

| Length of initial hospital stay after Tx in days: median (IQR) (date of discharge–date of admission) | 7.0 (5.0–9.0) | 6.0 (5.0–10.0) | <0.001† |

| Treatment for acute rejection in the first year % | 12.7 | 12.7 | 0.066* |

*χ2 -test proportions.

†Mann-Whitney test.

Tx, transplantation.

bmjopen-2015-010482supp_table.pdf (38.6KB, pdf)

Results did not change when models were repeated with weekend transplant status redefined as either Friday–Saturday or Sunday–Monday. In addition, when each day of the week was examined individually with Monday as the referent group, day of the week was not significantly associated with any of the outcomes after adjustment for multiple covariates (data not shown).

Discussion

In this large study that included over 136 000 deceased donor single organ kidney transplants performed in the USA over two decades, we noted no significant association between weekend transplantation status and patient and allograft outcomes, which was very robust for adjustment for covariates. No matter how we defined it or what variables we added to the model, there was still no association found between the day of the week and outcomes. Although patient and allograft survival are the most important outcome measures for transplantation, assessment of secondary outcomes helps delineate the potential adverse effects associated with weekend kidney transplantation. We did not find any significant impact of weekend transplant surgery on the secondary outcomes including 1-month or 1-year patient or allograft survival, delayed allograft function or acute rejection in the first year. The only difference noted was the slightly lower hospital length of stay with transplants performed over the weekend (Saturday and Sunday) versus the regular workweek (Monday–Friday) after adjustment for confounding factors. However, owing to the very large sample size, the power of our study was extremely large. Consequently, non-significant results very much support the interpretation that there are no differences. On the other hand, significant results have to be checked for relevance, as was the case, for example, for length of stay and cold ischaemia time variables which were both significant but not relevantly different between weekdays and weekends.

The only previous study that has looked at the impact of weekend transplantation status on patient and allograft survival was in liver transplant recipients.17 In this analysis from the UNOS database of nearly 100 000 liver transplants, the impact of both weekends and night-time on transplant outcomes at 30, 90 and 365 days was assessed. No adverse impact of night-time or weekend transplantation was found on patient survival. Only a modest increase in allograft failure (HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.11) was found at 365 days for weekend transplants. The authors consider their findings to be a testimony to the safety of current practices covering weekend and off-hour transplant procedures. However, the long-term allograft and patient survival was not assessed in this study. In the current study, both long-term and short-term outcomes for deceased donor kidney transplantation did not differ by weekday or weekend transplant status, but we could not assess the impact of night-time transplantation on the outcome owing to the lack of data on the time of transplantation in the UNOS database. A few single centre studies have shown conflicting results regarding the effect of night-time transplant surgery on outcome after kidney transplantation; however, the impact of weekend surgery was not assessed in any of these studies.20–22

Delivery of care in the perioperative period of deceased donor kidney transplantation can be complex and challenging. Efficiency and a high level of coordination and technical skills are required throughout the process of transplantation from harvest of the allograft to its implantation into the recipient. Shortfalls in any of these steps during weekends may potentially affect outcomes of transplantation. There may be several possible explanations for the lack of ‘weekend effect’ on outcomes after kidney transplantation in this study. The setting of deceased donor kidney transplantation differs from acute critical illness in that the patients coming for transplantation are typically clinically stable. Therefore, in this situation, confounding due to differences in severity of illness at the time of admission is much less likely compared to other clinical situations. Furthermore, the presence of well-defined protocols for every aspect of care in these patients, routine performance of kidney transplants over weekends, slower pace of the surgery compared to other emergency procedures, urgent management of all transplant-related procedures and performance of the surgery by experienced surgeons may make this group of patients less susceptible to the ‘weekend effect’. One may argue that the use of the conventional designation of a weekend, Saturday–Sunday, may not be the right time frame to analyse the ‘weekend effect’ of the immediate preoperative or postoperative care on the outcome. However, even on examining other definitions of weekend transplant status such as ‘Friday-Saturday’ or ‘Sunday-Monday’, no effect was noted between weekend transplant status and primary or secondary outcomes. In fact, the outcome was essentially not affected by any day of the week, indicating that the quality of hospital care delivered to kidney transplant recipients was consistent across all days of the week including the weekends. These results underscore the importance of a collaborative and dedicated team approach to care and the availability of standardised protocols for transplantation throughout the week. The lack of the weekend effect found on the outcomes in this setting is reassuring and alleviates concerns that may exist regarding the outcome of kidney transplantation performed during weekends. It would also be important to determine the association between weekend surgery and outcomes after transplantation of other organs such as heart, lungs or small bowel, where the patients are much sicker and the surgical procedure is more complicated than kidney transplantation.

Our study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that examined the impact of kidney transplant surgery performed on weekends versus weekdays on patient and allograft survival. Furthermore, we also evaluated the long-term outcomes. Our study used a nationally representative cohort of deceased donor single organ kidney transplant recipients. Our analyses adjusted for multiple confounding factors and findings were similar regardless of adjustment for covariates. Furthermore, we also looked at other definitions of weekend, that is, Friday–Saturday and Sunday–Monday, to investigate the impact of immediate preoperative or postoperative care because of the weekend on the previous or the following day, respectively. However, there are also some limitations, which are mostly inherent to the retrospective design and use of registry data. There is a potential for residual confounding from factors that are not captured in the database (eg, the working hours of the surgeons), or are difficult to measure or if there is a bias associated with differences in ascertainment of outcomes (eg, biopsy-proven acute rejection). The analyses are based on the assumption that coding errors and missing data are stochastic. Owing to incompleteness of reporting, we could not assess the rate of postoperative complications by day of transplantation. Furthermore, we could not analyse for centre-specific effects in this study, since data provided by UNOS to outside individual (non-UNOS or Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients) investigators have centre identifiers removed at the time of data transfer. However, since the overall results were null, we did not expect any significant centre-specific effects. Overall, our findings reflect transplantation practices in the setting of well-staffed tertiary centres in the USA that perform deceased donor kidney transplantation routinely, and may not be generalisable to all geographic regions worldwide. Therefore, further work will be required to assess whether deceased donor kidney transplants performed during weekends in other settings have similar outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, on the basis of the observations from this large retrospective study using US national registry data, we conclude that performance of kidney transplant surgery on weekends does not negatively affect short-term or long-term patient outcomes. The operationalisation of deceased donor kidney transplantation may provide a model for other procedures and surgeries that occur over the weekend, and may help reduce the length of hospital stay and improve outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-370011C.

Footnotes

Contributors: SB-A provided substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, data acquisition and analysis, interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. PM provided substantial contributions to the data acquisition and analysis, interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. HK provided substantial contributions to data acquisition and analysis, interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the work for important intellectual content. HF provided substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the work for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services and nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organisations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med 2001;345:663–8. 10.1056/NEJMsa003376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW et al. . Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1099–109. 10.1056/NEJMoa063355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoh BL, Chi YY, Waters MF et al. . Effect of weekend compared with weekday stroke admission on thrombolytic use, in-hospital mortality, discharge disposition, hospital charges, and length of stay in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample Database, 2002 to 2007. Stroke 2010;41:2323–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.591081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horwich TB, Hernandez AF, Liang L et al. . Weekend hospital admission and discharge for heart failure: association with quality of care and clinical outcomes. Am Heart J 2009;158:451–8. 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James MT, Wald R, Bell CM et al. . Weekend hospital admission, acute kidney injury, and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;21:845–51. 10.1681/ASN.2009070682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaheen AA, Kaplan GG, Myers RP. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from gastrointestinal hemorrhage caused by peptic ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:303–10. 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ensminger SA, Morales IJ, Peters SG et al. . The hospital mortality of patients admitted to the ICU on weekends. Chest 2004;126:1292–8. 10.1378/chest.126.4.1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakhuja A, Schold JD, Kumar G et al. . Outcomes of patients receiving maintenance dialysis admitted over weekends. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;62:763–70. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nandyala SV, Marquez-Lara A, Fineberg SJ et al. . Comparison of perioperative outcomes and cost of spinal fusion for cervical trauma: weekday versus weekend admissions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:2178–83. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang J, Saposnik G, Silver FL et al. . Association between weekend hospital presentation and stroke fatality. Neurology 2010;75:1589–96. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fb84bc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nanchal R, Kumar G, Taneja A et al. . Pulmonary embolism: the weekend effect. Chest 2012;142:690–6. 10.1378/chest.11-2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suissa S, Dell'Aniello S, Suissa D et al. . Friday and weekend hospital stays: effects on mortality. Eur Respir J 2014;44:627–33. 10.1183/09031936.00007714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orandi BJ, Selvarajah S, Orion KC et al. . Outcomes of nonelective weekend admissions for lower extremity ischemia. J Vasc Surg 2014;60:1572–9 e1. 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.08.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruiz M, Bottle A, Aylin PP. The Global Comparators project: international comparison of 30-day in-hospital mortality by day of the week. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:492–504. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aylin P, Alexandrescu R, Jen MH et al. . Day of week of procedure and 30 day mortality for elective surgery: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics. BMJ 2013;346:f2424 10.1136/bmj.f2424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voltz R, Kamps R, Greinwald R et al. . Silent night: retrospective database study assessing possibility of “weekend effect” in palliative care. BMJ 2014;349:g7370 10.1136/bmj.g7370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orman ES, Hayashi PH, Dellon ES et al. . Impact of nighttime and weekend liver transplants on graft and patient outcomes. Liver Transpl 2012;18:558–65. 10.1002/lt.23395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/ContentDocuments/OPTN_Policies.pdf (accessed 2015).

- 19.Rao PS, Ojo A. The Alphabet Soup of Kidney Transplantation: SCD, DCD, ECD—Fundamentals for the Practicing Nephrologist. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1827–31. 10.2215/CJN.02270409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seow YY, Alkari B, Dyer P et al. . Cold ischemia time, surgeon, time of day, and surgical complications. Transplantation 2004;77:1386–9. 10.1097/01.TP.0000122230.46091.E2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fechner G, Pezold C, Hauser S et al. . Kidney's nightshift, kidney's nightmare? Comparison of daylight and nighttime kidney transplantation: impact on complications and graft survival. Transplant Proc 2008;40:1341–4. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.02.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kienzl-Wagner K, Schneiderbauer S, Bösmüller C et al. . Nighttime procedures are not associated with adverse outcomes in kidney transplantation. Transpl Int 2013;26:879–85. 10.1111/tri.12125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010482supp_table.pdf (38.6KB, pdf)