Abstract

Objectives

To explore factors influencing the likelihood of antenatal vaccine acceptance of both routine UK antenatal vaccines (influenza and pertussis) and a hypothetical group B Streptococcus (GBS) vaccine in order to improve understanding of how to optimise antenatal immunisation acceptance, both in routine use and clinical trials.

Setting

An online survey distributed to women of childbearing age in the UK.

Participants

1013 women aged 18–44 years in England, Scotland and Wales.

Methods

Data from an online survey conducted to gauge the attitudes of 1013 women of childbearing age in England, Scotland and Wales to antenatal vaccination against GBS were further analysed to determine the influence of socioeconomic status, parity and age on attitudes to GBS immunisation, using attitudes to influenza and pertussis vaccines as reference immunisations. Factors influencing likelihood of participation in a hypothetical GBS vaccine trial were also assessed.

Results

Women with children were more likely to know about each of the 3 conditions surveyed (GBS: 45% vs 26%, pertussis: 79% vs 63%, influenza: 66% vs 54%), to accept vaccination (GBS: 77% vs 65%, pertussis: 79% vs 70%, influenza: 78% vs 68%) and to consider taking part in vaccine trials (37% vs 27% for a hypothetical GBS vaccine tested in 500 pregnant women). For GBS, giving information about the condition significantly increased the number of respondents who reported that they would be likely to receive the vaccine. Health professionals were the most important reported source of information.

Conclusions

Increasing awareness about GBS, along with other key strategies, would be required to optimise the uptake of a routine vaccine, with a specific focus on informing women without previous children. More research specifically focusing on acceptability in pregnant women is required and, given the value attached to input from healthcare professionals, this group should be included in future studies.

Keywords: pregnancy, attiitudes, clinical trial, Group B streptococcus, maternal immunisation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a large-scale study reporting the responses of over a thousand women of childbearing age in the UK.

A wide range of clinically important questions were included regarding both current antenatal vaccines and potential clinical trials which will be of relevance to practitioners and researchers in the UK and worldwide.

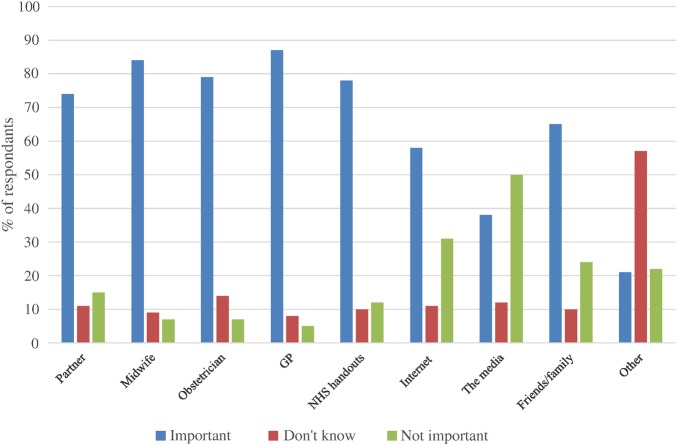

A relatively small proportion of women (2%) were actually pregnant at the time of the study and data on the women's ethnicity were not collected.

Though an online survey enables a large number of participants to be included, it is limiting in terms of the depth of information that can be gathered. However, it can provide a useful preliminary study to a more in-depth investigation using qualitative methods.

Introduction

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is the most common cause of sepsis and meningitis in infants up to the age of 3 months with a significant morbidity and mortality.1 2 Current prevention strategies (using intrapartum antibiotics) are aimed only at early onset group B strep infections (occurring in the first week of life) and there are a number of challenges in their application in developed and developing countries.3 Antenatal vaccination is therefore an attractive prospect, and the clinical trial of a candidate group B strep vaccine is currently in phase II development.

Despite the promise of antenatal immunisation against group B strep, it is important to be mindful that uptake rates for existing antenatal vaccines are relatively low. In England, antenatal influenza immunisation uptake was 44.1% in 2014/2015,4 despite clear benefits for the mother and child.5 Similarly, although antenatal immunisation against neonatal pertussis has an effectiveness of 91%6 and has been shown to be safe,7 uptake rates in the UK are currently at 56.4%, a contributing factor to the continuing tragedy of infant deaths from this illness.8 It is therefore evident that simply the availability of a safe and effective antenatal vaccine does not guarantee that it will be accepted by pregnant women, and it is important to consider the relevance of this for antenatal group B strep immunisation.

This paper presents further analysis of a previously published online survey,9 in which we reported that 72% of British women of childbearing age described themselves as ‘likely’ to receive a (hypothetical) antenatal vaccine against group B strep, a figure that increased to 82% when further information about invasive group B strep disease was provided. Presented here is a detailed analysis of the relative differences in attitudes across subgroups of age, disease knowledge and parental status to determine factors associated with increased likelihood of vaccine acceptance or refusal.

Methods

An online survey assessed awareness, perceptions of seriousness and acceptability of antenatal vaccines for three conditions: ‘whooping cough (also called pertussis) in newborn babies’, ‘influenza in women while pregnant’ and ‘GBS (group B strep) infection in newborn babies’. Preferred sources of advice about antenatal vaccination were also investigated. The full survey questions and response categories are included in table 1. For the question ‘How serious do you think the following conditions are?’, a non-infectious condition, ‘Heavy bleeding in pregnancy’ was used as a comparison as it was assumed that the majority of women would consider this a serious condition. A five-level Likert scale was used for all questions with the exception of one free-text answer.

Table 1.

Survey questions and possible responses

| Question | Possible responses |

|---|---|

| 1. Which one of the following statements best describes your current situation? |

|

2. How familiar are you with the following conditions?

|

|

3. How serious do you think the following conditions are?

|

|

4. How likely or unlikely would you be willing to receive the following vaccines during pregnancy?

|

|

|

Information provided about group B strep Group B strep is the UK’'s most common cause of meningitis and life-threatening infection in newborn babies. About 20% of UK women carry group B strep bacteria without having any symptoms. Babies can be exposed at birth and afterwards from the mother and from other sources. Most will not develop infection but about 600–700 babies a year in the UK do. Currently, antibiotics can be given during labour if the mother is considered to be at high risk of having a baby with group B strep infection, but this does not prevent all infections. A vaccine for pregnant women to protect their babies against group B strep is being developed. This vaccine has so far been given to many adults and to a small number of pregnant women in research studies. These studies have found no evidence of harm to the women or their unborn babies and the results suggest that the vaccine could prevent most group B strep infections in babies. | |

| 5. After reading the description above, how likely or unlikely would you be willing to receive a vaccine against group B strep during pregnancy? |

|

| 6. Could you explain why you would be likely/unlikely to be willing to receive a vaccine against group B strep during pregnancy? |

|

7. Specifically, how likely or unlikely would you be willing to receive a group B strep vaccine during pregnancy in each of the following situations?

|

|

8. Please indicate how important, or otherwise, you would consider the advice of each of the following in making a decision as to whether or not you would be comfortable to receive (or for your partner to receive) a group B strep vaccine during pregnancy.

|

|

GP, general practitioner; NHS, National Health Service.

A link to the survey was emailed to a nationally representative sample of 1221 women aged between 18 and 44 years in England, Scotland and Wales by a market research company (ComRes, London, 13–17 September 2013). These women had previously agreed to receive emails from ComRes with surveys on a range of topics including health, politics and social issues. Participation was voluntary and no personal identifying information was collected. Owing to the nature of this survey, formal ethical approval was not required.

Demographic details were also collected including age, social class, region and whether or not the respondent had any children or was planning to have more children. No personal identifying information was collected. Respondents were assigned a social class based on their reported occupation according to the Market Research Society guidelines.10 Social classes were defined according to the National Readership Survey classifications (available from http://www.nrs.co.uk/nrs-print/lifestyle-and-classification-data/social-grade/) and ranged from A to E, with A defined as being the highest social class and E the lowest. Weighting adjustments were applied to ensure a nationally representative sample.

Statistical comparisons between groups were carried out using χ2 tests, Fisher's exact test or χ2 test for trend using a software package (Graphpad prism V.6). For clarity of presentation in the tables, answers to questions 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 were collapsed into ‘don't know what it is’, ‘know what it is’ and ‘have been directly affected’ for question 2; ‘serious’, ‘not serious’ and ‘don't know’ for question 3; ‘likely’, ‘unlikely’ and ‘don't know’ for questions 4, 5 and 7; and ‘important’, ‘not important’ and ‘don't know’ for question 8. Where significant differences were found between subcategories, for example, ‘never heard of it’ and ‘heard of it but don't know what it is’ in question 2, these are indicated in the text. The full breakdown of answers is publicly available at http://www.comres.co.uk/poll/1028/gbs-vaccination-survey.htm. Free-text responses to the question, ‘Why would you be willing/unwilling to have a group B strep vaccine in pregnancy?’ were analysed for recurrent themes and grouped accordingly, for example, ‘to protect my baby's health’ or ‘do not like/believe in vaccines’.

Quality control measures used to ensure that respondents were paying due attention included a series of logic checks such as matching date of birth with age band and asking participants to identify shapes and colours.

Results

Of the 1221 women surveyed, 1013 returned usable answers (83%). Of those who did not, 138 (11%) did not complete the survey, 13 (1%) did not meet the inclusion criteria (eg, incorrect age or gender), 12 (1%) completed the survey after the recruitment target had been reached and 43 (4%) were discounted as they failed quality control. The proportions of respondents with and without children are shown in figure 1 and the numbers in each age category in table 2. Twenty-five per cent of the respondents were in social classes A and B (higher and intermediate managerial/professional), 29% in C1 (supervisory, clerical and junior managerial/professional), 17% in C2 (skilled manual) and 29% in DE (semiskilled, unskilled and unemployed). These social class percentages are similar to that of the 2011 household census for England and Wales.11

Figure 1.

Distribution of respondents by parental status. N=1013 women aged 18–44 years.

Table 2.

Survey responses by age, parental status and previous knowledge of the condition

| 18–24 years (% of n=239) | 25–34 years (% of n=359) | 35–44 years (% of n=415) | p Value | Children (% of n=570) | No children (% of n=443) | p Value | Know what it is (% of n†) | Don't know what it is (% of n†) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How serious would you consider the following conditions? | ||||||||||

| Heavy bleeding in pregnancy | ||||||||||

| Serious | 91 | 94 | 96 | 0.03 | 96 | 91 | 0.0011 | |||

| Don't know | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 7 | |||||

| Not serious | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0.002 | 1 | 2 | NS | |||

| Pertussis | ||||||||||

| Serious | 82 | 86 | 94 | <0.0001 | 92 | 83 | <0.0001 | 92 | 79 | <0.0001 |

| Don't know | 11 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 12 | 4 | 18 | |||

| Not serious | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0.003 | 3 | 5 | NS | 4 | 3 | NS |

| Influenza | ||||||||||

| Serious | 81 | 80 | 85 | NS | 85 | 80 | NS | 88 | 74 | <0.0001 |

| Don't know | 14 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 21 | |||

| Not serious | 5 | 8 | 6 | NS | 8 | 4 | 0.0268 | 7 | 5 | NS |

| Group B strep | ||||||||||

| Serious | 72 | 75 | 86 | <0.0001 | 84 | 72 | <0.0001 | 92 | 71 | <0.0001 |

| Don't know | 21 | 20 | 12 | 12 | 24 | 4 | 26 | |||

| Not serious | 7 | 4 | 1 | 0.0014 | 3 | 4 | NS | 5 | 3 | NS |

| How likely would you be to have a vaccine for the following conditions in pregnancy? | ||||||||||

| Pertussis | ||||||||||

| Likely | 75 | 76 | 72 | NS | 79 | 70 | 0.0018 | 77 | 67 | 0.0013 |

| Don't know | 18 | 15 | 19 | 12 | 23 | 44 | 25 | |||

| Unlikely | 6 | 9 | 9 | NS | 9 | 7 | NS | 8 | 8 | NS |

| Influenza | ||||||||||

| Likely | 73 | 72 | 70 | NS | 75 | 68 | 0.0211 | 76 | 65 | 0.0002 |

| Don't know | 18 | 16 | 18 | 12 | 23 | 11 | 26 | |||

| Unlikely | 9 | 12 | 12 | NS | 13 | 9 | 0.0437 | 12 | 9 | NS |

| Group B strep (pre information) | ||||||||||

| Likely | 72 | 72 | 72 | NS | 77 | 65 | <0.0001 | 79 | 67 | <0.0001 |

| Don't know | 22 | 19 | 20 | 14 | 28 | 11 | 25 | |||

| Unlikely | 6 | 10 | 8 | NS | 9 | 7 | NS | 10 | 8 | NS |

| Group B strep (post information) | ||||||||||

| Likely | 80 | 81 | 85 | NS | 86 | 77 | <0.0001 | 86 | 80 | 0.0217 |

| Don't know | 13 | 11 | 10 | 7 | 16 | 7 | 14 | |||

| Unlikely | 6 | 8 | 5 | NS | 6 | 6 | NS | 7 | 6 | NS |

Answers were mutually exclusive and p values indicate differences between groups for that answer versus all other answers.

NS, non-significant, that is, p>0.05. Percentages are rounded to the nearest whole number.

†Know what it is: pertussis n=727, flu n=609, group B strep n=374. Don't know what it is: n=286, flu n=404, group B strep n=639.

Factors influencing awareness and attitudes to pertussis, influenza and group B strep

Though similar proportions of respondents had been directly affected by each of the conditions (pertussis 5%, influenza 3% and group B strep 4%), less was known about group B strep compared with pertussis or influenza (‘never heard of’—pertussis: 6%; influenza: 14%; group B strep: 29%, p<0.0001). Those with children were significantly more likely than those without to know about each condition (see table 2), as were older women compared with younger women. However, as expected, older women were also more likely to have children (percentage with children: 18–24y ears: 26%, 25–34 years: 54%, 35–44 years: 74%, p<0.0001). There were no statistically significant differences in awareness by social class.

Older women, those with children and those with knowledge of the relevant condition were more likely to consider pertussis and group B strep to be serious; for influenza, the differences were not significant (table 2). Generally, a higher proportion of respondents rated pertussis as more serious compared with both influenza and group B strep (pertussis 88% vs influenza 82%, p=0.0002; pertussis 88% vs group B strep 79%, p<0.0001). However, of those who reported that they knew what the specific condition was or had experienced it themselves; 92% rated both pertussis and group B strep as either very serious or fairly serious. A higher proportion of these respondents who knew about group B strep also rated it as very serious, rather than fairly serious compared with pertussis (67% vs 59%, p=0.0037).

Factors influencing attitudes to immunisation and clinical trials

The likelihood of accepting antenatal vaccination for all three conditions was not affected by age (table 2) or social class (pertussis: AB 77%, C1 73%, C2 79%, DE 72%; influenza: AB 74%, C1 69%, C2 77%, DE 69%; and group B strep: AB 75%, C1 68%, C2 76%, DE 70%; all comparisons non-significant). Those who already had children or knew about the condition were significantly more likely to be willing to receive a vaccine in pregnancy (table 2). Giving information about group B strep significantly increased the likelihood of accepting an antenatal vaccine in all groups (table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of providing information about group B strep (see table 1) on likelihood of being willing to receive a group B strep vaccine in pregnancy

| Group | Preinformation (%) | Postinformation (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 years (n=239) | 185 (72) | 208 (80) | 0.0236 |

| 25–34 years (n=359) | 255 (72) | 289 (81) | 0.0038 |

| 35–44 years (n=415) | 286 (72) | 337 (85) | <0.0001 |

| Children (n=557) | 428 (77) | 481 (86) | <0.0001 |

| No children (n=456) | 297 (65) | 352 (77) | <0.0001 |

| Prior knowledge (n=374) | 297 (79) | 321 (86) | 0.0262 |

| No prior knowledge (n=639) | 429 (67) | 512 (80) | <0.0001 |

Eight-hundred and ninety-eight respondents commented in the free-text section about the reasons why they would or would not accept antenatal group B strep vaccination. Of those who reported that they would be likely to accept the vaccine, the most frequently expressed views were a desire ‘to protect my baby/baby's health’ (27%) and the vaccine being a preventive measure (15%). Forty-three respondents stated that they would need more information before making a final decision and 12 questioned the risks/safety of the vaccine. Of those who would be unwilling to have an antenatal group B strep vaccine, 24% (16/63) stated that they did not like/believe in vaccines with the next most common issue being that they required more information (19%, 13/63) or felt there was a lack of safety evidence (17%, 11/63).

A specific recommendation for use by the National Health Service (NHS), as opposed to the vaccine simply being licensed and available, significantly increased the likelihood of respondents accepting the group B strep vaccine (79% vs 52%, p<0.0001), proportions that remained higher in those with previous knowledge about group B strep (table 4).

Table 4.

Likelihood of accepting group B strep vaccine in four difference scenarios by age, parental status and previous knowledge of group B strep

| How likely would you be to have a group B strep vaccine in the following situations? | 18–24 years (% of n=239) | 25–34y ears (% of n=359) | 35–44 years (% of n=415) | p Value | Children (% of n=557) | No children (% of n=456) | p Value | Know what it is (% of n=374) | Don't know what it is (% of n=639) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Licensed and recommended | ||||||||||

| Likely | 78 | 79 | 80 | NS | 81 | 76 | NS | 83 | 77 | 0.0163 |

| Don't know | 15 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 16 | |||

| Unlikely | 8 | 9 | 6 | NS | 7 | 7 | NS | 7 | 8 | NS |

| Licensed, not specifically recommended | ||||||||||

| Likely | 56 | 52 | 50 | NS | 52 | 52 | NS | 57 | 49 | 0.0132 |

| Don't know | 17 | 19 | 21 | 18 | 21 | 16 | 21 | |||

| Unlikely | 27 | 29 | 29 | NS | 30 | 27 | NS | 27 | 30 | NS |

| Part of a research study, previously tested in 5000 pregnant women | ||||||||||

| Likely | 50 | 44 | 38 | 0.0139 | 46 | 40 | NS | 47 | 41 | NS |

| Don't know | 19 | 15 | 21 | 16 | 21 | 16 | 20 | |||

| Unlikely | 31 | 40 | 41 | 0.0247 | 38 | 38 | NS | 38 | 38 | 0.0246 |

| Research study, previously tested in 500 pregnant women | ||||||||||

| Likely | 34 | 35 | 28 | NS | 37 | 27 | 0.0009 | 36 | 30 | 0.0435 |

| Don't know | 21 | 17 | 24 | 19 | 23 | 18 | 23 | |||

| Unlikely | 45 | 48 | 47 | NS | 44 | 50 | NS | 46 | 47 | NS |

Answers were mutually exclusive and p values indicate differences between groups for that answer versus all other answers.

NS, non-significant, that is, p>0.05.

A smaller proportion of women were likely to receive an antenatal group B strep vaccine as part of a research study than if licensed (42% (if previously given to 5000 women) or 32% (if previously given to 500 pregnant women) vs 52% (if licensed but not routinely recommended)). In early stage development (ie, vaccine administered to fewer than 500 pregnant women), previous knowledge of group B strep increased the likelihood of respondents being willing to take part in a research study; however, it made no difference to this decision if the vaccine had been given to 5000 pregnant women (table 4). Age and social class made no difference to the proportion of women willing to take part in group B strep vaccine research, but a higher percentage of those who already had children reported that they would be likely to be willing to receive a group B strep vaccine as part of a clinical trial (table 4).

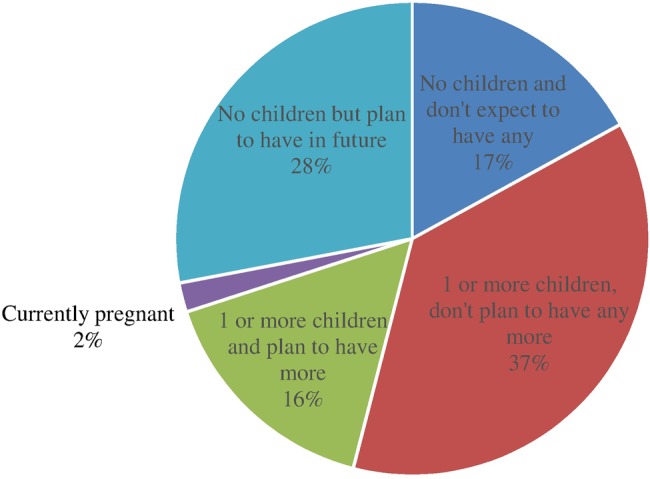

Sources of advice

The importance to women of advice from various sources in making decisions about antenatal vaccination is shown in figure 2. General practitioners (GPs) were the source of advice rated as important by the highest proportion of respondents (87%) closely followed by midwives (84%). Twenty per cent more women felt that written NHS handouts were more important compared with internet sources such as parent forums (78% vs 58%) and half indicated that the media was not an important source of advice for them. Generally, older respondents (35–44 years) were more likely to rate advice from maternity health professionals as important than the youngest age group (midwife: 18–24 years (79%), 35–44 years (87%), p<0.01; obstetrician: 18–24 years (69%), 35–44 years (86%), p<0.0001), women aged 25–34 years also followed this trend (group differences were statistically significant for obstetricians but not midwives). However, younger women were more likely to rate advice from friends and family as important (18–24 years (72%), 25–34 years (64%), 35–44 years (62%), p<0.005). There were no significant age group differences in ratings for partners, the internet or the media. Those with children rated each of the sources as more important than those without children, although those without children were more likely to answer ‘don't know’.

Figure 2.

The important of advice from various sources of information when making decisions on antenatal vaccination. GP, general practitioner; NHS, National Health Service.

Discussion

These findings emphasise the critical importance of information about group B strep to optimise uptake of a potential antenatal vaccine, and that this may need to be specifically targeted at women in their first pregnancy. Even a brief explanation about group B strep increased the likelihood of vaccine acceptance by 7–13% and a specific national recommendation for its use significantly increased the potential uptake rate; however, it is important to combine this information with other strategies to promote uptake. Women of childbearing age rate the importance of advice from healthcare professionals, particularly their GP, very highly.

This survey forms part of a larger project funded by Meningitis Now entitled ‘Preparing the UK for an effective Group B streptococcus vaccine’, and was designed to provide preliminary information on the views of the UK population about GBS and a possible antenatal vaccine. The potential for vaccination against group B strep is particularly important as a trivalent glycoconjugate vaccine has recently been trialled in over 300 pregnant women with no vaccine-related safety concerns and large-scale clinical trials are likely to begin in the near future.12 13 Universal antenatal vaccination against group B strep could have several advantages over intrapartum antibiotics. It would most likely protect against both early-onset and late-onset disease, while intrapartum antibiotics are only able to prevent early-onset infection. Concerns about antibody resistance and the practical issue of administering intravenous antibiotics at least 2 h before birth would no longer be relevant. This is particularly important as in one UK study, 81% of mothers whose babies went on to develop group B strep disease had not received adequate intrapartum antibiotics, despite having risk factors.14 Primary prevention through vaccination could potentially avoid these situations; however, more information is needed on the immunogenicity and safety of the vaccine and, most importantly, whether or not it would be acceptable to pregnant women.

While it is encouraging that over 70% of respondents reported that they would be likely to have antenatal vaccinations against the three conditions surveyed, in reality vaccine uptake is much lower. The peak uptake for antenatal pertussis vaccine in England was 61.5% in November 2013 and has since fallen,8 15 despite guidelines that it should be routinely offered to all pregnant women in the UK between 28 and 38 weeks' gestation.16 The percentage of pregnant women receiving the influenza vaccine, which is recommended for all pregnant women in the UK regardless of gestation during the influenza season, is only around 44.1%.4 The reasons for these low rates are varied and much of the published work has focused on influenza vaccination in pregnancy.

A number of strategies to promote antenatal vaccine uptake have been tried, again particularly focusing on immunisation against influenza. In Stockport, Greater Manchester, UK, antenatal influenza vaccination uptake increased by almost 15% over 1 year through concentrated efforts using local media/social media, establishing links between midwifery and GP services, improving IT services, education of staff and good leadership.17 Similarly, an Australian campaign based on raising health professionals' awareness of antenatal influenza vaccination through lectures and meetings, new patient information booklets and visual reminders on patient notes increased influenza vaccine uptake from 30% to 40%.18 Our results also indicate that knowledge about the condition being prevented and support from healthcare professionals are key, and even brief interventions, such as the short paragraph about group B strep used in this survey, can significantly impact on the likelihood of vaccine uptake.

There is less information regarding attitudes towards antenatal group B strep vaccination, but this is a growing area of research. A recently published survey of 231 pregnant or recently delivered women in the USA showed remarkably similar results to this survey in that 79% of respondents indicated that they would be likely to have a group B strep vaccine in pregnancy.19 Although 90% indicated that they were concerned about the safety of new antenatal vaccines, 95% of those surveyed responded that they generally followed their healthcare professional's recommendations. A Canadian qualitative study also found that a healthcare professional's recommendation would be a major factor in whether or not they would accept the vaccine, and concerns about safety were also raised.20 Our findings suggest that while there are certain groups who may be more receptive to antenatal vaccination, there are others, such as women in their first pregnancy, who may require additional input to encourage vaccine uptake. These women may be more accepting if the antenatal vaccines are nationally recommended and may require extra time and provision of information to optimise discussion of vaccination options, particularly those focusing on the nature and seriousness of the conditions that are being vaccinated against.

There are a number of limitations to these findings that must be acknowledged. Respondents to the survey had volunteered to receive such questionnaires on multiple occasions and on various topics and therefore may be more open to research in general. There were few pregnant women within the sample and it is the views of these women, for whom the questions are not merely theoretical, which are key. However, the sample was relatively large and representative in terms of age, geography and social class, and therefore provides a useful framework on which to build future work. Of note, data on the women's ethnicity were not collected, which may be an important factor. The nature of an online survey also means that in-depth exploration of the decision-making process is not possible and more detail is needed on women's information requirements and how this should be delivered. Other details are lacking, such as how women self-defined being directly affected by the condition and why such a high proportion of women who did not know what the conditions were still rated them as serious. The rates reported here are higher than the invasive disease rates and some of those without children also considered themselves to have been directly affected by each of the conditions suggesting response bias. This may have been the result of confusion over what was being asked in this question or this group may contain relatives/friends of affected parents or women who have had a positive group B strep swab in pregnancy, rather than an affected child. However, this is consistent across all the conditions surveyed and it seems that this experience is sufficient to sway attitudes towards group B strep.

It is with these limitations in mind that further research on the acceptability of group B strep immunisation in pregnant women in the UK is being conducted using focus groups, interviews and questionnaires to specifically obtain the views of pregnant women and maternity healthcare professionals. If these findings support the data presented here, then, depending on the development of an effective and safe vaccine, immunisation of pregnant women against group B strep could be the next major breakthrough in the prevention of neonatal sepsis and meningitis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the respondents to the online survey and E Di Antonio and Holly Wicks (ComRes) for assistance with survey preparation.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Jane Plumb at @JanePlumb

Contributors: FM wrote the article which was reviewed by all authors. Data analysis was performed by FM, MDS and MV. All authors contributed to the design of the online survey.

Funding: This survey was funded by a grant from Meningitis Now (formerly Meningitis UK), grant number 6000.

Competing interests: PTH serves as a consultant to Novartis Vaccines regarding group B strep vaccine development. MDS has participated in advisory boards and/or been an investigator on clinical trials of vaccines sponsored by vaccine manufacturers including Novartis Vaccines, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Crucell and Sanofi Pasteur. Payment for these services was made to the University of Oxford Department of Paediatrics. MDS has had travel and accommodation expenses paid to attend conferences by Novartis Vaccines and GlaxoSmithKline. JP is the Chief Executive of Group B Strep Support, a charity which offers support and information to families affected by group B strep. She informs health professional about the prevention of group B strep infection and supports research into preventing these infections in newborn babies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Okike IO, Ribeiro S, Ramsay ME et al. Trends in bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal meningitis in England and Wales 2004–11: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:301–7. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70332-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Sánchez PJ et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Early onset neonatal sepsis: the burden of group B Streptococcal and E. coli disease continues. Pediatrics 2011;127:817–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, The prevention of early-onset Group B streptococal disease. 2012: Green Top guidelines No 36. 2nd Edition published 01 July 2012. https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg36/ (accessed 02 Feb 2016).

- 4. Public Health England. Influenza immunisation programme for England: data collection survey season 2014–2015. 2015: PHE publications gateway number: 2015046. published May 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/429612/Seasonal_Flu_GP_Patient_Groups_Annual_Report_2014_15.pdf (accessed 14 Apr 2016).

- 5.Zaman K, Roy E, Arifeen SE et al. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1555–64. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H et al. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet 2014;384:1521–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60686-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donegan K, King B, Bryan P. Safety of pertussis vaccination in pregnant women in UK: observational study. BMJ 2014;349:g4219 10.1136/bmj.g4219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Public Health England. Prenatal pertussis immunisation programme 2014/2015: annual vaccine coverage report for England. 2015, PHE publications gateway number 2015282. published September 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/457733/PrenatalPertussis_Final.pdf (accessed 14 Apr 2016).

- 9.McQuaid F, Jones C, Stevens Z et al. Attitudes towards vaccination against group B streptococcus in pregnancy. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:700–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Market Research Society. Occupational Groupings: a Job Dictionary. Sixth ed. London: Market Research Society, 2006.

- 11.Office of National Statistics. 2011 Census: quick statistics for England and Wales based on national identity, passports held and country of birth 2013. (cited 5 Feburary 2016). http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-286348

- 12.Madhi SA, Leroux-Roels G, Koen A et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an investigational maternal trivalent vaccine to prevent perinatal group B streptococcus (GBS) infection. ESPID conference; 30 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slobod K. Novartis group B streptococcus vaccine programme. Meningitis Research Foundation Conference London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vergnano S, Embleton N, Collinson A et al. Missed opportunities for preventing group B streptococcus infection. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2010;95:F72–3. 10.1136/adc.2009.160333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Public Health England, P.H., Pertussis vaccine coverage for pregnant women by month 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pertussis-immunisation-in-pregnancy-vaccine-coverage-estimates-in-england-october-2013-to-march-2014/pertussis-vaccination-programme-for-pregnant-women-vaccine-coverage-estimates-in-england-october-2013-to-march-2014 (accessed 6 Feb 2016).

- 16. Public Health England, Pertussis (whooping cough) immunisation for pregnant women. Updated March 2014. http://www.hpa.org.uk/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/WhoopingCough/ImmunisationForPregnantWomen/

- 17.Baxter D. Approaches to the vaccination of pregnant women: experience from Stockport, UK, with prenatal influenza. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013;9:1360–3. 10.4161/hv.25525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy EA, Pollock WE, Nolan T et al. Improving influenza vaccination coverage in pregnancy in Melbourne 2010-2011. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2012;52:334–41. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2012.01428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dempsey AF, Pyrzanowski J, Donnelly M et al. Acceptability of a hypothetical group B strep vaccine among pregnant and recently delivered women. Vaccine 2014;32:2463–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patten S, Vollman AR, Manning SD et al. Vaccination for group B streptococcus during pregnancy: attitudes and concerns of women and health care providers. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:347–58. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]