Abstract

Objectives

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) are considered key elements in the development of effective health promotion. However, there is little research to back the enthusiasm for these partnerships. Our objective was to describe the diversity of visions on PPPs and to assess the links between the authors and corporations engaged in such ventures.

Methods

We reviewed the scientific literature through PubMed in order to select all articles that expressed a position or recommendation on governments and industries engaging in PPPs for health promotion. We included any opinion paper that considered agreements between governments and corporations to develop health promotion. Papers that dealt with healthcare provision or clinical preventive services and those related to tobacco industries were excluded. We classified the articles according to the authors' position regarding PPPs: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree. We related the type of recommendation to authors' features such as institution and conflicts of interest. We also recorded whether the recommendations were based on previous assessments.

Results

Of 46 papers analysed, 21 articles (45.6%) stated that PPPs are helpful in promoting health, 1 was neutral and 24 (52.1%) were against such collaborations. 26 papers (57%) set out conditions to assure positive outcomes of the partnerships. Evidence for or against PPPs was mentioned in 11 papers that were critical or neutral (44%) but not in any of those that advocated collaboration. Where conflicts were declared (26 papers), absence of conflicts was more frequent in critics than in supporters (86% vs 17%).

Conclusions

Although there is a lack of evidence to support PPPs for health promotion, many authors endorse this approach. The prevalence of ideas encouraging PPPs can affect the intellectual environment and influence policy decisions. Public health researchers and professionals must make a contribution in properly framing the PPP issue.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, ETHICS (see Medical Ethics), EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study provides information on an unexplored area: the influence on the scientific environment through editorials and commentaries supporting public–private partnerships between governments and corporations for health promotion.

The study made a highly sensitive bibliographical search and screened a large sample of manuscripts.

However, the study was circumscribed to those engagements between governments and corporations arranged to promote health and excluded other types of public–private partnerships.

Introduction

There is a growing interest in using public–private partnerships (PPPs) to address health-related issues. Most of the actions in global health engage in diverse arrangements that could be considered to be PPPs.1 In provision of healthcare services, these hybrid partnerships have become a common approach. The range of the collaborations in purpose, design and composition is so broad that it challenges the efforts from the academic field to evaluate their merit and efficiency in improving health outcomes. There is a wave of enthusiasm accepting that engagement in partnerships is an ineluctable path towards improvements in population health. This movement has been fuelled by several global institutions and numerous articles in the lay and scientific literature. Buse, in collaboration with other authors,1–3 has made a thorough description of the origin of PPPs at the global level, weighted their risks and opportunities, and has advocated for the evaluation of these so-called global health governance instruments.

Either encouraged by this fervour or working from their own agenda, some governments have introduced partnerships with corporations as a key element of health strategies. Richter,4 in 2004, analysed the movement towards closer interactions of United Nations agencies and the business sector with particular reference to the WHO. She warned of political pressures and the tendency towards weakening rather than strengthening safeguards for public interests when building these public–private interactions. However, these partnerships in health promotion benefit from the halo of theoretical success and respect accrued in global health by providing drugs for neglected diseases and similar endeavours.

Regardless of the potential merits of global health partnerships, the question of governments engaging with corporations in order to promote health is a central issue in present public health and should be the object of careful research. The intellectual environment can be propitious to PPPs if many articles published in scientific journals assume that these agreements are a cornerstone of new public health developments. Consequently, when considering the role of corporations (manufacturers of beverages, food, alcohol, etc) in public health policy, the potential capture of research is worth studying. There is reliable evidence to show how industries have altered science in order to avoid public concern on some health issues.5 Furthermore, the setting up of organisations or research centres committed to partnerships could contribute to an increase in the number of positive articles appearing in the scientific literature.

A review was performed of articles (mainly editorials and commentaries on PPPs published in scientific journals) in order to quantify the diversity of views, and to assess the links between the authors and corporations engaged in such ventures.

Methods

The aim of our review was to identify opinion papers on PPPs designed to promote health by collaboration between governments and those industries the products of which are related to disease regardless of the participation of other partners (eg, non-governmental organisations (NGOs)). The term PPP was defined as voluntary and collaborative relationships between various parties, both state and non-state, in which all participants agree to work together to achieve a common purpose or to undertake a specific task, and to share risks, responsibilities, resources, competencies and benefits.6 The term PPP has been used to define many types of interaction that involve a range of different actors and goals. We restricted our study to those agreements of which the objective was health promotion, understood as the process of enabling people to increase control over and to improve their health.7 Therefore, we excluded PPPs of which the objectives were provision of healthcare or clinical preventive services, research, development or distribution of products (drugs, vaccines, etc). We performed a bibliographical search through PubMed in MEDLINE, using keywords from seminal papers on PPPs. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the bibliographical search, keywords employed and search strings. In the first step, we found 665 entries that we reviewed in order to refine the inclusion criteria and to detect inconsistencies between observers in article classification. One complication we encountered was making decisions on whether the papers referred to health promotion and whether the private sector partner involved was related to the causes of disease. In some cases, the papers mentioned health promotion but in fact they dealt with healthcare provision or clinical preventive services. On the other hand, some industries were linked to the origin of disease by their negative externalities, that is, the cost imposed by industries on third parties such as the health costs to the population caused by endocrine disruptors derived from the chemical industry. After this preliminary search and review, we refined our inclusion criteria in order to choose articles that were opinion papers on PPPs (comments, editorials, viewpoints, etc) in which the public partner was from public administration and the private partner any business directly related to the disease that the PPP was intended to prevent, such as producers of sweetened beverages, alcohol or foods containing high transunsaturated fatty acids. Partnerships in industries indirectly related to disease by negative externalities were excluded. We also excluded papers on PPPs of which the objective was scientific research, cooperation for development, healthcare provision or preventive services. We discarded reports on partnerships between either governments or business with NGOs because governments have several capacities, such as regulatory power, that can be captured or modified by industries. Partnerships between industries and NGOs do not endanger these risks. However, we have not excluded papers on PPPs in which NGOs or other civil organisations have participated provided there is at least an agreement between a public administration and an industry. Finally, we did not include papers on the relations between public authorities and the tobacco industry, as they have been extensively studied in the past and rejected as an acceptable option.

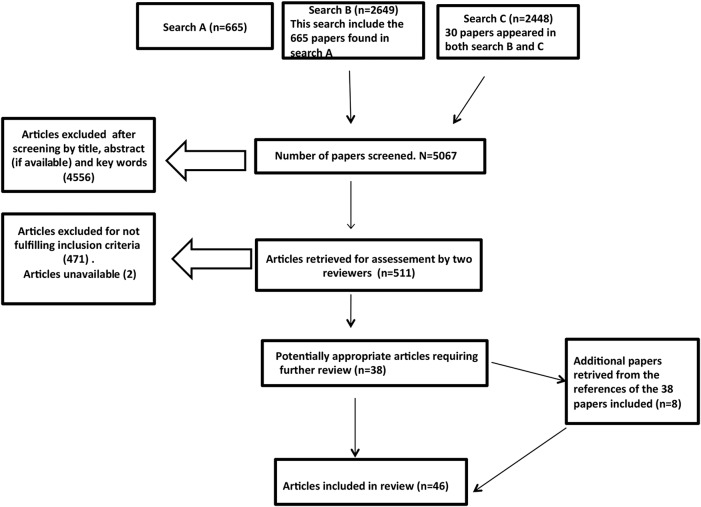

Figure 1.

Flow diagram on process of identifying and screening studies for inclusion. Search A: (‘Public Health’ [All Fields] OR ‘Health Promotion’ [All Fields]) AND (‘Public-Private Sector Partnerships’ [All Fields] OR (‘public-private sector partnerships’ [MeSH Terms] OR (‘public-private’ [All Fields] AND ‘sector’ [All Fields] AND ‘partnerships’ [All Fields]) OR ‘public-private sector partnerships’ [All Fields] OR (‘public’ [All Fields] AND ‘private’ [All Fields] AND ‘partnerships’ [All Fields]) OR ‘public private partnerships’ [All Fields])). Search B: public private partnership OR public private partnerships. Search C: (‘Public Health’ [All Fields] OR ‘Health Promotion’ [All Fields]) AND (‘Alcoholic Beverages’ [All Fields] OR ‘Public-Private Sector Partnerships’ [All Fields] OR ‘Public Private Partnerships’ [All Fields] OR (‘chronic disease’ [MeSH Terms] OR (‘chronic’ [All Fields] AND ‘disease’ [All Fields]) OR ‘chronic disease’ [All Fields]) OR ‘Food Industry’ [All Fields] OR ‘Private Sector’ [All Fields] OR ‘Public Sector’ [All Fields] OR ‘Motor Activity’ [All Fields] OR ‘World Health’ [All Fields] OR ‘global health’ [mh] OR ‘Tobacco Industry’ [All Fields] OR ‘Public Policy’ [All Fields]) AND (Editorial[ptyp] OR Comment[ptyp]) AND (Comment[ptyp] OR Editorial[ptyp]).

In a second step, and in order to maximise sensitivity, we performed a simple search with the following terms: ‘public private partnership or public private partnerships’ (figure 1), which produced 2649 papers. As some well-known papers on the field were not detected through this search, we adopted a new strategy using terms from missed papers in the previous search and found 2418 additional papers. After screening (title, key words, abstract if available and full text in case of doubt), we selected 38 papers. Finally, we completed the search through citation tracking of these 38 articles and retrieved 29 new papers, 9 of which fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The final number of papers reviewed was 47.8–53 The search was performed in June 2015. Two papers were unavailable and therefore excluded.

The main variables drawn from the papers were: the position of the paper on PPPs (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree); the full text of the comments on which the stance of the author was based; the conditions for engagement in PPPs, if any; the statement of conflict of interest; and author affiliation. In order to determine whether the author had relations with corporations involved in PPPs, either directly or through any form of partnership, we used author affiliation and statements of conflicts of interest, and, finally, we also performed an extensive Google search.

The initial analysis of papers (n=10) was blind and carried out by the two authors, who agreed on six papers. After consensus on the application of inclusion criteria and assessment of the results on main variables was reached, we completed an additional blind analysis (n=12). The authors agreed on nine papers and proceeded with the remaining articles. The final analysis of all the papers included was performed by both authors.

Results

Forty-six editorials or commentaries in scientific journals argued either for or against PPPs in health promotion. Twenty three of the papers (50%) focused on PPPs in the promotion of healthy nutrition; 8 (17%) were on PPPs related to alcohol use; and 15 (32%) referred to PPPs that considered general rather than specific types of health promotion. Of the 28 journals that published the opinion articles on PPPs, Addiction printed 7, SCN News printed 5 and PLoS Medicine printed 3. The other journals, mainly from the public health field and nutrition, published between 1 and 2.

One of the 46 articles was classified as neutral, 21 (45.6%) supported PPPs, 16 strongly supported partnerships and 24 (51.1%) did not recommend engaging in partnerships; 21 were strongly against.

Most of the papers (19, or 41%) were published in public health journals, of which 10 were in favour of PPPs. Of the 11 papers published in nutrition journals, 8 supported PPPs. In the subject category of substance abuse, five articles out of seven were against PPPs. The articles published in general medicine journals were mainly opposed (five out of six).

As expected, there were differences in the relations of the authors with partnerships. Among advocates of PPPs, 13 (62%) had worked or were working in PPPs, while among critics of PPPs, the figure was 6 (25%). No statement on conflict of interest was included in 20 of the papers (43%), and there was no difference between supporters of PPPs (9–43%) and critics (10–42%). When a declaration of conflicts of interest was required (26 papers), absence of conflicts was acknowledged or proved in 14 (54%); with a significant difference between defenders and critics of PPPs (17% vs 86%).

The main reasons for supporting PPPs can be categorised as follows (table 1): (1) the magnitude of the endeavour is too great and neither the public nor the private sector alone can address the issues; (2) the quality of public and private health actions increases through public–private collaboration; (3) PPPs contribute to putting health on the agenda of other actors/sectors; (4) a PPP is a good instrument for the improvement of self-regulation and (5) PPPs encourage the manufacture of healthful products by industry.

Table 1.

Advantages of PPPs suggested by authors who support this strategy

| Types of arguments | Quotations from reviewed papers* |

|---|---|

| Threats to health cannot be tackled by governments alone |

|

| PPPs enrich the capacity, quality and reach of public health services. Industries can benefit from public health service expertise |

|

| PPPs help to put health in all policies |

|

| PPPs improve self-regulation |

|

| Reducing unhealthful products and improving the quality of products |

*Some quotations have been abridged for inclusion in the table.

NGO, non-governmental organisation; PPP, public–private partnership.

Authors critical of PPPs give as their main arguments the following (table 2): (1) profits from unhealthful products or services are irreconcilable with public health because of unavoidable conflicts of interests; (2) PPPs confer legitimacy on industries that produce unhealthful commodities; (3) regulatory capture; (4) precautionary principle and lack of evidence and (5) the objectives of PPPs contradict public health priorities.

Table 2.

Main arguments against public–private partnerships (PPPs) suggested by authors critical of this strategy

| Types of arguments | Quotations from reviewed papers* |

|---|---|

| Alliances between public health and the private sector of which the products or services are unhealthful have inherent conflicts of interest that cannot be reconciled. |

|

| Collaboration in health promotion confers legitimacy and credibility on industries that produce disease related products. PPPs can damage the credibility of public health institutions. |

|

| PPPs capture institutions (UN agencies, governments, etc), regulatory bodies and science. |

|

| Precautionary principle due to lack of evidence. |

|

| Objectives of PPPs contradict public health priorities. |

|

*Some quotations have been abridged for inclusion in the table.

Regardless of the attitudes of papers to PPPs, 26 (57%) set out requirements to assure positive outcomes of the partnerships. Some of the recommendations were general, and supported the need for appropriate checks and balances in order to align the financial interests of the industry with the goals of public health. Others were very clear about the conditions for engagement with corporations and two papers gave detailed explanation of the criteria proposed.24 32 The conditions for partnerships with industries can be grouped as follows (table 3): (1) general principles, design and management of PPPs; (2) criteria for partner selection and (3) role of corporations.

Table 3.

Conditions for engaging in PPPs put forward by the authors

| Type of conditions | Quotations from papers reviewed* |

|---|---|

| General principles, design and management of PPPs |

|

| Criteria for partner selection, both type of industry/activity and individual companies |

|

| Role of corporations |

|

*Some quotations have been abridged for inclusion in the table.

NCD, non-communicable disease; PPP, public–private partnership.

When assessing whether or not the statements of the authors regarding PPPs were evidence based, we found that reference to their effectiveness was the exception: only 11 articles (23%) made mention of data supporting their arguments. Reference to evidence was made only by the articles considered as neutral or critical of PPPs (44%). None of the supporters of partnerships mentioned evidence of their effectiveness.

Discussion

PPPs, which emerged in the last century, particularly in global health, are becoming an accepted way to implement health promotion programmes. Our study shows that there are contradictory opinions on the benefits and drawbacks of such partnerships. While most of the authors critical of this endeavour base their arguments on evidence of the effectiveness (or lack of effectiveness) of PPPs, this is much less true of authors supportive of PPPs. Moreover, advocates of partnerships are frequently linked to PPPs or to the companies involved. Regardless of the position of the authors, the impression given by most papers is that PPPs are here to stay. Consequently, many authors offer recommendations for governments when they engage in such partnerships. The main weakness of our study may be related to the ubiquitous use of the term PPP for a wide array of collaborations between different partners and for a broad spectrum of purposes. In fact, PPPs have a positive halo of suitability derived from their application in global health where most partnerships are based on products, product development or service provision. We were interested only in those partnerships built to promote health in which the partners are on the one hand public administration and on the other, corporations of which the products, or some of them, can be considered as harmful. These partnerships fail to exclude products and services that jeopardise the theoretical objective of promoting health. However, it has proven difficult to distinguish completely between those papers that express an opinion on the PPPs of which the goal is exclusively health promotion, and those papers that offer viewpoints on PPPs with any other aims. On the other hand, we think that this is a feature of the field of private public collaborations where some experience supports the general idea that partnerships are good for population health and that they should be included in the main strategies of public health administrations. In any case, we think that our selection of papers has been strict enough to confine the papers revised to those that analyse health promotion. It is possible that we have excluded some relevant papers; however, we have chosen specificity to ensure that we are considering articles that give an opinion on partnerships in health promotion.

Regarding conflicts of interest and relations of authors with PPPs or corporations engaged directly with PPPs, the scarcity of information provided in the papers makes it difficult to carry out a comprehensive assessment. We opted for a Google search, and we were able to find sufficient information on authors and to identify their relations with corporations. However, there are at least two shortcomings. First, we are unaware of any links between authors and any institution, partnership or corporation if this information is not available on internet. Second, the potential conflicts of interest of PPP critics are more subtle; for instance, civil servants convinced that decision-making in public health belongs exclusively to the government. Consequently, our results on conflicts of interest may have failed to include all factors.

The number of papers finally included was 47, but it should be mentioned that at least three authors who were critical of PPPs have two papers in the list. One author who supported partnerships has three papers and another has two papers. We did not exclude these papers, as arguments and co-authors were not identical.

We are not aware of any research into opinions on PPPs and therefore cannot contrast our results with other studies. One may wonder why opinion papers on PPPs are relevant when we, in public health, tend to rely on evidence. First of all, evidence on PPPs for health promotion is scarce; although some evidence-based reports on the effectiveness of PPPs have appeared,54–57 opinion papers still affect the intellectual environment. As Macintyre58 has pointed out, influences in policy are heterogeneous and evidence is not the main factor. The intellectual environment in which policymakers operate receives many inputs and, consequently, we believe that we need to be aware of any source of influence. Cultural capture is an example of government or regulatory capture—when government or regulatory actions serve the ends of industry.59 In public health policy, the decision-makers' perspectives and actions are likely to be tinged by the prevalent ideas in the public space and relationship networks. A surplus of information favourable to PPPs by think tanks and the permeation in scientific journals of articles encouraging PPPs as the inevitable solution to the main public health challenges could have an impact in policymaking. This hypothesis is difficult to test and our results do not provide an answer. However, we wish to underline the apparent paradox in the number of articles favourable to PPPs when evidence on their effectiveness is scarce and does not support this strategy. If we had not limited the scope of our research to health promotion, the number of favourable articles to PPPs would have been still higher, but this vision could be based on some evidence of PPPs that have been successful in the provision of services or medicines. We think that the general tide in favour of PPPs could be affecting the non-critical incorporation of this strategy in public health policy.

Why does the scientific environment portray an overoptimistic view of PPPs as shown in our results? The decision of some governments, multilateral institutions and regulatory agencies to engage with non-state for-profit actors could be a cause and effect of this environment favourable to PPPs. In fact, the role of the United Nations agencies might have been relevant. As Buse and Harmer1 described so well, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as neoliberal ideologies influenced public policy and attitudes, relationships began to change and influential international organisations acknowledged and championed a greater role for the private sector. During 1990s, there was a clear development of PPPs in the United Nations, including the WHO, of which the causes and landmarks have been well described by Richter.4 In 1990, Gro Harlem Brundtland (Director General of the WHO from 1998 to 2003) had already supported the need for partnerships between all actors as the only acceptable formula to address global challenges. She was also extremely clear on the issue when addressing the Fifty-fifth World Health Assembly: “Only through new and innovative partnerships can we make a difference. And the evidence shows we are. Whether we like it or not, we are dependent on the partners…to bridge the gap and achieve health for all….”49 Several governments around the world, the European Union, and such relevant agencies as the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, have been also promoting partnerships with the private sector.4 18 32 40 Two issues are worth highlighting. First, the claim that partnerships are a strategy based on evidence; and second, the confusion that can arise because of the indiscriminate use of the term ‘partnerships’ to label any type of interaction between governments and industry.

In terms of the former, such claims are striking as, to date, we lack adequate evidence to recommend or reject PPPs. There are certainly some evaluations on the effects of PPPs as aforementioned54–57; however, it is too early to conclude that partnerships with the private sector are a healthy alternative to compulsory approaches. Our results show that advocates of PPPs seldom mention any evidence to endorse their opinions. Authors critical of partnerships refer more often to evidence. The policy implication of the aforementioned evaluations and of our own results is that more assessments of PPPs, and more evidence synthesis on the effectiveness and safety of these types of collaborations are needed. Nevertheless, until more sound scientific evidence is available, governments should be cautious before engaging in collaboration with industries that are responsible for the main health problems.

Regarding the latter—the identification of partnerships—we agree with those authors who call for clarification in the use of this term.4 9 The concept of partnership has been used inaccurately to refer to any relationship, including governments, multilateral institutions and industries. This fact could sow confusion on the roles and obligations of the different actors in collaborations. Partnership implies that the actors involved have the same status, which contributes to the trend of giving voice to corporations at the policy table. Richter suggests renaming PPPs as public–private interactions or using less value-laden terms that identify the category or subcategory of the interaction that best facilitates identification of conflicts of interest. She also recommends clear and effective institutional policies and measures that put the public interest at centre stage in all public–private interactions.4 The clear identification of any interaction of governments with industry might prevent non-evidence-based collaboration and allow the application of appropriate criteria when interaction with industry or any other stakeholder is required.

In fact, the availability of sound principles would be valuable in interactions with private corporations. However, we think that there is a requisite regarding the presence of corporations at the policy decision table. Some authors are very clear on this point60 61: Galea and McKee24 point out: “It should never be the case that governments abdicate their responsibility for policy making to the corporate sector.” This reasonable restriction is linked to concerns about accountability, which is avoided if policy decisions are transferred to PPPs. This does not constitute a veto of any interaction with corporations. On the contrary, practical policy should consider all relevant inputs, whenever equity in democratic participation of all stakeholders is guaranteed.

Our results refer to partnerships for health promotion. In this area, the first test proposed by Galea and McKee is wholly pertinent: “are the core products and services provided by the corporation health enhancing or health damaging?” Although some could raise doubts on the potential deleterious effects of some commodities such as some foods or alcohol, the portrayal must be completed with the overall health impact of corporate practices. As has been highlighted, public health researchers should pay more attention to corporate practices as a social determinant of health.62

The suggestion that PPPs favour intersectoral action, given as a reason to support them, should be taken with caution. The argument invoked is that promoting health, for instance by favouring healthful diets and physical activity, requires a shared responsibility across many sectors, including government and industry. In public health, such sectors mean primarily non-health areas. On the other hand, of course, all stakeholders should have a voice in the process. Unfortunately, to date, industries have more opportunities and resources to reach centres of decision-making compared with wide sectors of the population. Furthermore, sharing responsibility could embrace many arrangements, and PPPs for health promotion have not shown relevant positive effects in population health.

In conclusion, our results show that, in spite of the scarcity of evidence on effectiveness, many comments or editorials in the scientific literature are clearly favourable to partnerships for health promotion between governments and industries the products of which are among the causes of major health problems. We think that rather than being anecdotal, this is a reflection of a growing general opinion in favour of PPPs regardless of their appropriateness for population health. The critics of the recent WHO position reflect the tension on this relevant global health question.63 In our view, this is a form of intellectual—scientific—capture. We agree with those authors who emphasise that the precautionary principle is fully applicable in this field as there is no evidence that the partnership of alcohol and ultraprocessed food and drink industries is safe or effective.10 46

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers for their useful comments and Jonathan Whitehead for language editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: IH-A contributed to the original design. IH-A and GAZ organised and carried out the systematic literature research and analysis of papers retrieved. IH-A drafted the manuscript, which was reviewed and approved by both authors. IH-A is the guarantor for this study.

Funding: This research was funded by the Ciber de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), which did not have any role in the decision to submit this manuscript or in its writing.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Buse K, Harmer AM. Seven habits of highly effective global public-private health partnerships: practice and potential. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:259–71. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buse K, Walt G. Global public-private partnerships: part II—what are the health issues for global governance? Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:699–709. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buse K, Walt G. Global public-private partnerships: part I—a new development in health? Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:549–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richter J. Public-private partnerships and international policy-making. How can public interests be safeguarded? Helsinki: Hakapaino Oy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiist WH. The corporate play book, health, and democracy: the snack food and beverage industry's tactics in context. In: Stuckler D, Siegel K, eds. Sick societies. Responding to the global challenge of chronic disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011:204–16. [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations. Enhanced cooperation between the United Nations and all relevant partners, in particular the private sector. Report of the Secretary-General to the General Assembly. Item 47 of the provisional agenda: Towards global partnerships. UN Doc. A/58/227 New York, 2003:4 http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N03/461/70/PDF/N0346170.pdf?OpenElement [Google Scholar]

- 7.Word Health Organization. Ottawa charter for health promotion. Geneva: WHO, 1986. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babor TF. Partnership, profits and public health. Addiction 2000;95:193–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brady M, Rundall P. Governments should govern, and corporations should follow the rules. SCN News 2011;39:51–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brownell KD. Thinking forward: the quicksand of appeasing the food industry. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001254 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruno K. Perilous partnerships: the UN's corporate outreach program. J Public Health Policy 2000;21:388–93. 10.2307/3343280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannon G. Out of the box. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:732 10.1017/S1368980009005370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmona RH. Foundations for a healthier United States. J Am Diet Assoc 2006;106:341 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciccone DK. Arguing for a centralized coordination solution to the public-private partnership explosion in global health. Glob Health Promot 2010;17:48–51. 10.1177/1757975910365224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa Coitinho D. Editorial. SCN News 2011;39:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dangour AD, Diaz Z, Sullivan LM. Building global advocacy for nutrition: a review of the European and US landscapes. Food Nutr Bull 2012;33:92–8. 10.1177/156482651203300202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Easton A. Public-private partnerships and public health practice in the 21st century: looking back at the experience of the Steps Program. Prev Chronic Dis 2009;6:A38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elinder LS. Obesity and chronic diseases, whose business? Eur J Public Health 2011;21:402–3. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fillmore KM, Roizen R. The new Manichaeism in alcohol science. Addiction 2000;95:188–90.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher JC. Can we engage the alcohol industry to help combat sexually transmitted disease? Int J Public Health 2010;55:147–8. 10.1007/s00038-010-0142-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedhoff Y, Hébert PC. Partnerships between health organizations and the food industry risk derailing public health nutrition. CMAJ 2011;183:291–2. 10.1503/cmaj.110085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freedhoff Y. The food industry is neither friend, nor foe, nor partner. Obes Rev 2014;15:6–8. 10.1111/obr.12128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedl KE, Rowe S, Bellows LL et al. . Report of an EU–US symposium on understanding nutrition-related consumer behavior: strategies to promote a lifetime of healthy food choices. J Nutr Educ Behav 2014;46:445–50. 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galea G, McKee M. Public–private partnerships with large corporations: setting the ground rules for better health. Health Policy 2014;115:138–40. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilmore AB, Fooks G. Global Fund needs to address conflict of interest. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:71–2. 10.2471/BLT.11.098442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilmore AB, Savell E, Collin J. Public health, corporations and the new responsibility deal: promoting partnerships with vectors of disease? J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33:2–4. 10.1093/pubmed/fdr008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomes F, Lobstein T. Food and beverage transnational corporations and nutrition policy. SCN News 2011;39:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawkes C, Buse K. Public-private engagement for diet and health: addressing the governance gap. SCN News 2011;39:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernández Aguado I, Lumbreras Lacarra B. [Crisis and the independence of public health policies. SESPAS report 2014]. Gac Sani 2014;28(Suppl 1):24–30. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jernigan DH. The global alcohol industry: an overview. Addiction 2009;104(Suppl 1):6–12. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jernigan D, Mosher J. Permission for profits. Addiction 2000;95:190–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kickbusch I, Quick J. Partnerships for health in the 21st century. World Health Stat Q 1998;51:68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.KraaK VI, Swinburn B, Lawrence M et al. . The accountability of public-private partnerships with food, beverage and quick-serve restaurant companies to address global hunger and the double burden of malnutrition. SCN News 2011;39:11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraak VI, Kumanyika SK, Story M. The commercial marketing of healthy lifestyles to address the global child and adolescent obesity pandemic: prospects, pitfalls and priorities. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:2027–36. 10.1017/S1368980009990267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraak VI, Story M. A public health perspective on healthy lifestyles and public-private partnerships for global childhood obesity prevention. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:192–200. 10.1016/j.jada.2009.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Lancet. Editorial. Trick or treat or UNICEF Canada. Lancet 2010;376:1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lang T, Rayner G. Corporate responsibility in public health. BMJ 2010;341:c3758 10.1136/bmj.c3758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lemmens P. Critical independence and personal integrity. Addiction 2000;95:187–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ludwig DS, Nestle M. Can the food industry play a constructive role in the obesity epidemic? JAMA 2008;300:1808–11. 10.1001/jama.300.15.1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Majestic E. Public health's inconvenient truth: the need to create partnerships with the business sector. Prev Chronic Dis 2009;6:A39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCreanor T, Casswell S, Hill L. ICAP and the perils of partnership. Addiction 2000;95:179–85. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9521794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKinnon R. A case for public-private partnerships in health: lessons from an honest broker. Prev Chronic Dis 2009;6:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mello MM, Pomeranz J, Moran P. The interplay of public health law and industry self-regulation: the case of sugar-sweetened beverage sales in schools. Am J Public Health 2008;98:595–604. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.107680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller D, Harkins C. Corporate strategy, corporate capture: food and alcohol industry lobbying and public health. Crit Soc Pol 2010;30:564–89. 10.1177/0261018310376805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monteiro CA, Cannon G. The impact of transnational “Big Food” companies on the south: a view from Brazil. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001252 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moodie R, Stuckler D, Monteiro C et al. . Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet 2013;381:670–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62089-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raw M. Real partnerships need trust. Addiction 2000;95:196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Remick AP, Kendrick JS. Breaking new ground: the Text4baby program. Am J Health Promot 2013;27:S4–6. 10.4278/ajhp.27.3.c2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richter J. Public–private partnerships for health: a trend with no alternatives? Development 2004;47:43–8. 10.1057/palgrave.development.1100043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singer PA, Ansett S, Sagoe-Moses I. What could infant and young child nutrition learn from sweatshops? BMC Public Health 2011;11:276 10.1186/1471-2458-11-276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuckler D, Nestle M. Big food, food systems, and global health. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001242 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yach D, Feldman ZA, Bradley DG et al. . Can the food industry help tackle the growing global burden of undernutrition? Am J Public Health 2010;100:974–80. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yach D, Khan M, Bradley D et al. . The role and challenges of the food industry in addressing chronic disease. Global Health 2010;6:10 10.1186/1744-8603-6-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roehrich JK, Lewis MA, George G. Are public-private partnerships a healthy option? A systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med 2014;113:110–19. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bryden A, Petticrew M, Mays N et al. . Voluntary agreements between government and business—a scoping review of the literature with specific reference to the Public Health Responsibility Deal. Health Policy 2013;110:186–97. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knai C, Petticrew M, Durand MA et al. . Are the Public Health Responsibility Deal alcohol pledges likely to improve public health? An evidence synthesis. Addiction 2015;110:1232–46. 10.1111/add.12855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Panjwani C, Caraher M. The Public Health Responsibility Deal: brokering a deal for public health, but on whose terms? Health Policy 2014;114:163–73. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Macintyre S. Evidence in the development of health policy. Public Health 2012;126:217–19. 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwak J. Cultural capture and the financial crisis. In: Carpenter D, Moss DA, eds. Preventing regulatory capture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014:71–98. [Google Scholar]

- 60.McPherson K. Can we leave industry to lead efforts to improve population health? No. BMJ 2013;346:f2426 10.1136/bmj.f2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hasting G. Why corporate power is a public health priority. BMJ 2012;345:e5124 10.1136/bmj.e5124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Freudenberg N, Galea S. The impact of corporate practices on health: implications for health policy. J Public Health Policy 2008;29:86–104; discussion 105 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richter J. Time to turn the tide: WHO's engagement with non-state actors and the politics of stakeholder governance and conflicts of interest. BMJ 2014;348:g3351 10.1136/bmj.g3351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]