Abstract

Introduction

In critically ill patients, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and ventilator-associated conditions (VACs) are associated with increased mortality, survivor morbidity and healthcare resource utilisation. Studies conclusively demonstrate that initial ventilator settings in patients with ARDS, and at risk for it, impact outcome. No studies have been conducted in the emergency department (ED) to determine if lung-protective ventilation in patients at risk for ARDS can reduce its incidence. Since the ED is the entry point to the intensive care unit for hundreds of thousands of mechanically ventilated patients annually in the USA, this represents a knowledge gap in this arena. A lung-protective ventilation strategy was instituted in our ED in 2014. It aims to address the parameters in need of quality improvement, as demonstrated by our previous research: (1) prevention of volutrauma; (2) appropriate positive end-expiratory pressure setting; (3) prevention of hyperoxia; and (4) aspiration precautions.

Methods and analysis

The lung-protective ventilation initiated in the emergency department (LOV-ED) trial is a single-centre, quasi-experimental before-after study testing the hypothesis that lung-protective ventilation, initiated in the ED, is associated with reduced pulmonary complications. An intervention cohort of 513 mechanically ventilated adult ED patients will be compared with over 1000 preintervention control patients. The primary outcome is a composite outcome of pulmonary complications after admission (ARDS and VACs). Multivariable logistic regression with propensity score adjustment will test the hypothesis that ED lung-protective ventilation decreases the incidence of pulmonary complications.

Ethics and dissemination

Approval of the study was obtained prior to data collection on the first patient. As the study is a before-after observational study, examining the effect of treatment changes over time, it is being conducted with waiver of informed consent. This work will be disseminated by publication of full-length manuscripts, presentation in abstract form at major scientific meetings and data sharing with other investigators through academically established means.

Trial registration number

Keywords: mechanical ventilation, ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, ARDS, ventilator-associated conditions

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first trial to specifically implement lung-protective ventilation in the emergency department, and to assess the intervention effect on outcome.

The pragmatic design will allow the enrolment of a large sample of diverse patients, increasing the external validity of findings.

The intervention is simple.

A before-after design can make proving causation difficult and can be affected by temporal changes in care.

There is no mechanistic outcome, which limits the ability to assess why exactly the intervention may be effective.

Introduction

In mechanically ventilated patients, pulmonary complications that occur during the course of critical illness are seminal events that can significantly alter the trajectory of patient outcome.1 2 Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and ventilator-associated conditions (VACs) are two categories of these complications that can occur, and are associated with an increase in mortality, survivor morbidity and healthcare resource utilisation.1 3

There are no treatment options that address the underlying pathophysiology of ARDS. However, increasing data suggest that certain modifiable variables, if addressed early, can prevent progression to ARDS. With a mortality rate of approximately 40%, primary prevention is likely the most effective strategy to improve outcome. Similar measures can prevent VACs, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Healthcare Safety Network (CDC/NHSN) view VACs as a quality measure for the management of mechanically ventilated patients. The emergency department (ED) is the entry point for hundreds of thousands of mechanically ventilated patients annually in the USA4. Many of these patients are at high risk for pulmonary complications, yet the ED remains a relatively unstudied location with respect to the prevention or mitigation of their occurrence. As ventilator-associated lung injury (VALI) has been shown to occur during the first few hours of mechanical ventilation, a preventive intervention in the ED, targeting these high-risk patients, could be the systematic programme needed to improve outcome.5 6

Cyclic alveolar overdistention from positive pressure ventilation is a key element in the pathogenesis of lung injury. VALI promotes inflammatory injury and can cause pulmonary complications in healthy lungs. Lung-protective ventilation, by limiting VALI, reduces mortality in critically ill mechanically ventilated patients.7 There is also a significant amount of data to suggest that initial ventilator settings are in the causal pathway for pulmonary complications after initiation of mechanical ventilation. Observational data, two systematic reviews and two randomised trials show that non lung-protective ventilation, delivered early in the course of respiratory failure, is associated with an increased incidence of pulmonary complications in previously non-injured lungs.2 8–16 Our preliminary data show that the early use of potentially injurious ventilation is common in ED patients.17 18 Furthermore, our data have shown that higher tidal volume delivered in the ED is associated with an increased incidence in pulmonary complications.19 Early initiation of lung-protective ventilation in the ED may therefore be an effective strategy to reduce complications in this vulnerable cohort. This has not been a target of previous research.

Owing to the abundance of data showing a strong association between initial ventilator settings and clinical outcomes, as well as the high safety and favourable risk-benefit profile, a default lung-protective ventilator strategy became the standard approach in our ED in 2014.20–22 To increase our understanding of the role of ED-based mechanical ventilation on the incidence of pulmonary complications, we designed the lung-protective ventilation initiated in the emergency department (LOV-ED) trial, a quasi-experimental, before-after study, with the objective of testing the efficacy of ED-based lung-protective ventilation in the prevention of pulmonary complications in mechanically ventilated ED patients.

Methods and analysis

Study design

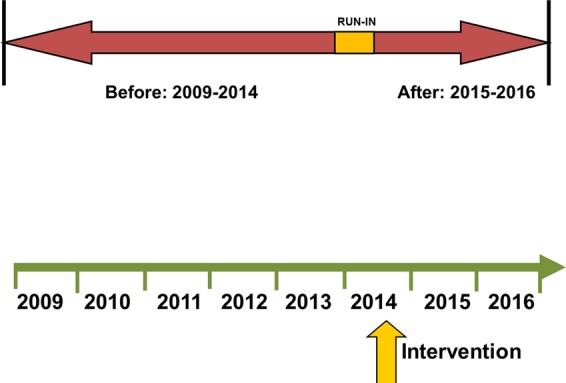

This is a single-centre, quasi-experimental, before-after study, and is reported in compliance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Intervention Trials (SPIRIT) statement (see online supplementary file). A schematic of the before-after trial design appears in figure 1. The hypothesis to be tested is that lung-protective ventilation, initiated in the ED, is associated with a reduced rate of pulmonary complications (ARDS and VACs).

Figure 1.

Schematic of before-after trial design.

bmjopen-2015-010991supp.pdf (313KB, pdf)

Study population

The preintervention group consists of mechanically ventilated ED patients from September 2009 to 2014; the postintervention group includes patients managed after the implementation of an ED-based mechanical ventilator protocol (October 2014). To improve protocol adherence, a run-in period of approximately 6 months was performed prior to study initiation. Inclusion criteria are: (1) adult patients aged ≥18 years; and (2) mechanical ventilation via an endotracheal tube. Exclusion criteria are: (1) death within 24 h of presentation; (2) discontinuation of mechanical ventilation within 24 h of presentation; (3) chronic mechanical ventilation; (4) presence of a tracheostomy; (5) transfer to another hospital from the ED and (6) fulfilment of ARDS criteria at hospital presentation.

Patients will be recruited exclusively from the ED at Barnes-Jewish Hospital/Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis. Based on the demographics of the patient population routinely presenting to our hospital, the resulting study population is expected to be approximately 55% male, 50% white, 45% African-American and 5% other races. We expect a similar distribution, but will enrol patients without regard to gender or race. We therefore expect that the study findings will hold external validity and be applicable to the community as a whole.

For the preintervention arm of the study, the Clinical Investigation Data Exploration Repository (CIDER) will be used to identify patients receiving mechanical ventilation in the ED. CIDER was developed to maintain electronic health records at Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Hospital sites, including both inpatient and outpatient encounters. To maximise the retrieval of all mechanically ventilated patients in the ED from our prespecified timeframe, we investigated three methods, utilising: (1) International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes, (2) current procedural terminology (CPT) codes and (3) a Boolean keyword search of ED documents. Results from a previously published prospective study were used as a test data set in order to validate this methodology and accurately retrieve the study cohort of all patients who were mechanically ventilated while in the ED.18 The Boolean keyword search method was observed to be the superior method over ICD-9 and CPT codes, and yielded retrieval with perfect precision (1.0). Therefore, for the current study, patients will be identified by querying CIDER using keyword extraction from ED documents. The final keyword search to identify the full cohort will be:+(‘intubation’ OR ‘intubated’) AND—(‘rapid sequence intubation induction’ AND ‘intubated patients’) AND+(‘ETT’ OR ‘ventilator settings’ OR ‘endotracheal tube’ OR ‘ET’) AND +(‘ETCO2’ OR ‘color change’ OR ‘ventilator’ OR ‘ventilator order’ OR ‘vent management’ OR ‘ET placement’ OR ‘capnography’ OR ‘sedation’ OR ‘resuscitation’).

For the prospective, postintervention arm of the study, screening for enrolment will be facilitated using an automated, electronic pager system (Computer-Assisted Subject Enrollment for the Emergency Department; CASE-ED). This system screens patients 24 h a day, 7 days a week. For the purposes of the current study, it will be programmed to trigger an alert for any one of the following: (1) an order for ventilator settings in the ED; (2) an order for neuromuscular blockers (eg, succinylcholine, rocuronium) or (3) documentation of endotracheal intubation. Furthermore, the bedside respiratory therapist will send a notification via email to the study principal investigator (PI) whenever mechanical ventilation is initiated on any patient. This approach has been used before and allows the capture of every patient receiving mechanical ventilation while in the ED.18

Interventions

A default lung-protective ventilation strategy was instituted in 2014 in our ED. It aims to improve adherence with principles of high-quality mechanical ventilation practice, and address the parameters in need of quality improvement, as demonstrated by our previous research: (1) prevention of volutrauma, (2) appropriate positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) setting, (3) limitation of hyperoxia and (4) aspiration precautions. The ED ventilator protocol is shown in figure 2. Briefly, after endotracheal intubation is accomplished and confirmed, the ED respiratory therapist will obtain an accurate height with a tape measure. Ventilator settings are then established according to the protocol in figure 2, and head-of-bed elevation is performed in all patients, unless specifically contraindicated by clinical care protocols (ie, head of bead elevation may be contraindicated in patients with suspected cervical spine fracture).

Figure 2.

ED protocol for mechanical ventilation in the immediate postintubation period. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ED, emergency department; PBW, predicted body weight; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; BMI, body mass index; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation; PaO2, partial pressure of arterial oxygen; iPEEP, intrinsic PEEP.

We take a pragmatic approach to the study design, and therefore co-interventions (eg, antibiotics and fluid management) that may influence the event rate for the primary outcome will not be standardised, and will be at the discretion of the treating clinician. While this introduces a potential risk of an imbalanced cohort for comparison, and therefore potential to limit the ability to detect an effect of the intervention, we have chosen this approach: (1) to maximise generalisability to the community as a whole; (2) because no systematic differences in care (excluding lung-protective ventilation) that may influence the event rate of interest have been introduced in the ED at Barnes-Jewish Hospital; (3) because an overwhelming majority of mechanically ventilated patients have been excluded in randomised trials, contributing to the poor implementation of critical care research findings in this cohort;23 and (4) because our ED has several processes of care that are already standardised via well-established protocols (ie, quantitative resuscitation for sepsis, transfusion), and/or order sets (ie, rapid sequence intubation, antibiotics, etc), which provides relative assurance for additional standardisation of care with respect to co-interventions. We will statistically analyse any potential differences in baseline characteristics, illness severity and process-of-care variables between the before and after groups.

Additional variables of interest include baseline demographics, comorbid conditions, vital signs at presentation, laboratory variables (including arterial blood gas and baseline oxygenation), illness severity scores (ie, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA)), location of intubation, ED length of stay and indication for initiation of mechanical ventilation. Treatment variables in the ED include intravenous fluid, receipt of blood products, central venous catheter and arterial catheter placement, antibiotics, and vasopressor use. Pertinent clinical data after admission will also be included. Table 1 and figure 3 show a full description of events for this study.

Table 1.

Schedule of events for the intervention study period (after group)

| ED presentation and endotracheal intubation | LPV protocol initiated in ED | ICU admit Day 1 |

Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Day 8–14 | Hospital discharge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | X | ||||||||||

| Demographics | X | ||||||||||

| Comorbidities | X | ||||||||||

| Illness severity scores | X | ||||||||||

| Vitals and laboratory data | X | ||||||||||

| ED treatment variables | X | ||||||||||

| ED ventilator data | X | ||||||||||

| ICU ventilator data (twice daily) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| SOFA score | X | X | |||||||||

| RASS score | X | X | |||||||||

| CAM-ICU | X | X | |||||||||

| Fluid balance | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Transfusion | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| ARDS outcome | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| VAC outcome | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Mortality | X | ||||||||||

| Other secondary outcomes | X |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CAM, confusion assessment method; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; LPV, lung-protective ventilation; RASS, Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; VAC, ventilation-associated condition.

Figure 3.

Planned operations for intervention study period (after group). ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; VAC, ventilator-associated condition; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest is a composite outcome of pulmonary complications after admission: ARDS and VACs. ARDS will be defined according to the Berlin definition, and will be analysed through day 7, as data suggest that the majority of ARDS cases will develop within this time period.17 18 24 25 Adjudication of ARDS status will occur in a systematic fashion, per the previously published standard operating procedure of our research team.18 Each investigator will review a set of training radiographs in order to reduce heterogeneity in X-ray interpretation, and will be blinded to ventilator settings.26 For patients with an equivocal ARDS adjudication status after primary review, an independent (blinded) expert investigator will further review the X-rays. Patients fulfilling ARDS oxygenation criteria within a 24 h window of having bilateral infiltrates not fully explained by myocardial dysfunction or fluid overload, will be deemed to have ARDS. VACs will be defined according to the CDC definition.1 Per these criteria, a patient must be mechanically ventilated for ≥4 days to qualify for a VAC. This includes 2 days of stable or improving ventilator settings, followed by 2 days of worsening oxygenation, represented by an increase in fraction of inspired oxygen of ≥0.20 (20%) or PEEP ≥3 cm H2O. Therefore, the denominator for VACs will be those patients ventilated ≥4 days. For the purposes of this study, the minimum PEEP level to define a VAC will be 2.5 cm H2O, as our experience shows that most PEEP changes at our centre occur in increments of 2.5 cm H2O. VACs will be analysed until day 14, as data suggest that the majority of VACs develop within this time period.1

Secondary outcomes include hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) lengths of stay, ventilator and vasopressor duration, and mortality.

Proposed statistical methods

There are two cohorts of interest: (1) a preintervention group, prior to the implementation of a lung-protective ventilator protocol; and (2) a postintervention group managed with a ventilator protocol as described above, and in figure 2. Categorical characteristics will be compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Continuous characteristics will be compared using the independent samples t test or Wilcoxon's rank-sum test. The primary analysis will compare the proportion of patients in each cohort with and without the occurrence of pulmonary complications (eg, ARDS or VACs) using logistic regression with propensity score (PS) adjustment. Multivariable logistic regression will be used to derive the PS, with cohort as the dependent variable. Cohort 2 patients will be categorizsd into quintile subclasses based on their ranked estimated PS and then matched to cohort 1 patients to achieve a similar distribution of covariates. Unmatched cases in cohort 1 will be discarded. Simple diagnostics and linear regression testing for a quintile by cohort interaction will be used to verify balance, and if not achieved, PSs will be re-estimated using transformations or interactions. In final logistic regression, the treatment effect is defined as the odds of pulmonary complication as a function of cohort, with adjustment for the quintiles of the PS. Development of ARDS and VACs will also be analysed separately. Secondary outcome variables will be compared using PS-adjusted logistic regression (mortality) and PS-adjusted Poisson regression (lengths of ICU/hospital stay, mechanical ventilation days). We will conduct a priori subgroup analyses to further understand the treatment effect and identify subgroups in which heterogeneous treatment effects exist. These subgroups include (but are not limited to) sepsis, trauma, neurological injury and presence of shock. Missing data will be handled by multiple imputation methods. On study completion, other statistical methods will be explored as necessary, and all analyses will be conducted in consultation with a biostatistician.

The sample size is calculated for the primary outcome, the development of pulmonary complications. We expect an event rate of approximately 20% in the before group.1 10 18 As a reflection of a decrease in VALI, we expect an absolute risk reduction of 5.4% for pulmonary complications in the after group. This will require a total sample size of postintervention participants of 513 to have 80% power. All tests will be two-tailed, and a p value <0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Data storage and management

All data will be entered by one research assistant and data accuracy will be verified by the study PI. Data quality control measures will include queries to identify missing data, outliers and discrepancies. Only the research assistant and study PI will have access to protected health information. After enrolment, a unique identifier (ID) will be assigned to each study participant. This ID will be linked to the participant's medical record number, and this hard copy roster will be stored in a locked cabinet in the PI's locked private office. All computers will be password-protected and encrypted per university policy. The PI will ensure that the anonymity is maintained. Patients will not be identified by name in any reports on this study. The study PI will have access to the final trial data set, as will a consulting biostatistician (in a de-identified state).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval

The study protocol received ethical approval by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University in St Louis School of Medicine (Institutional Review Board identification number 201409024) prior to beginning the study. As the study is a before-after observational study, examining the effect of treatment changes over time, it was conducted with waiver of informed consent.

Dissemination and data sharing

Sharing of data generated by this project is an essential part of the proposed activities and will be shared with collaborators as soon as available. It will be carried out in several different ways. Data and resources will be shared with other eligible investigators through academically established means. Results will be made available both to the community of scientists interested in mechanical ventilation and ARDS to avoid unintentional duplication of research. Collaboration with others investigators interested in establishing lung-protective ventilation protocols in the ED will be welcomed. On completion of all follow-up data, this work will be published as full-length manuscripts and presented in abstract form at national meetings in critical care medicine and emergency medicine.

Discussion

Critical care medicine has historically been practiced within the walls of the ICU. However, there is increased recognition of the large number of critically ill and at-risk patients cared for outside the ICU (eg, ED, hospital ward, operating room). Provision of time-sensitive therapy prior to ICU arrival can save lives, and providing ‘critical care without walls’ is now recognised as a major priority to improve outcome.27

This has yet to extend on a large scale to the clinical practice or study of mechanical ventilation in the ED. We believe there is opportunity to improve outcome by targeting this cohort, given that: (1) >200 000 patients are ventilated in the ED in the USA annually, and these numbers are increasing4 28 29; (2) lengths of stay in the ED are sufficient to induce lung injury30; (3) there is a clear temporal link between pulmonary complications and admission from the ED17–19 25; (4) initial ventilator management influences outcome, both for patients with, and at risk for, ARDS2 8–16 31; and (5) ventilator settings in the ED are often in the injurious range and have been linked to ARDS development.17–19

The LOV-ED trial was designed to assess the role of ED-based mechanical ventilation on the prevention of pulmonary complications after admission to the ICU. This is the first trial to specifically implement lung-protective ventilation in the ED, and to assess the intervention effect on outcome.

Our study has several strengths. In prior randomised trials of patients with ARDS, 80–90% of screened patients are excluded.23 This likely contributes to poorly generalisable results to the community as a whole, and poor subsequent implementation of lung protection.32 As a pragmatic, quasi-experimental study, the LOV-ED trial will enrol a large sample of diverse patients, and the design will allow capture of all eligible patients, increasing the external validity of findings. Complex critical care interventions have also been implemented poorly in the ED.33 The intervention is also simple and with little-to-no increased cost. It will also be implemented from the initiation of mechanical ventilation by non-physician providers (ie, respiratory therapists), allowing this strategy to be universally applied per protocol in any ED if the LOV-ED trial demonstrates benefit. Finally, the pragmatic design does not mandate the control of co-interventions, increasing its external validity.

The study also has some limitations. The before-after study design can make proving causation difficult. Given the abundance of preclinical and clinical data, including our data from the ED, a randomised trial would have ethical implications with respect to equipoise. Before-after studies are also hindered by temporal changes and imbalance between groups; these will be analysed and reported in our results. The effect of the intervention (and power of the trial) will be reduced if adherence to the protocol is poor and patients do not receive it. Adherence will be assured in several ways. The intervention is relatively simple, easy to apply and well tolerated, which is associated with greater adherence in clinical studies. A run-in period will be used prior to the beginning of the study, in which respiratory therapists and emergency medicine clinicians will be educated regarding the importance of adherence and scientific merit of the intervention. Finally, we will track adherence in real time and provide feedback and recommendations via electronic mail if there was no identifiable reason for protocol non-adherence. The effect of the intervention could also be reduced if ICU ventilator settings are vastly different than those received in the ED. Based on our previous work, we do not expect this to occur.18 The ventilator protocol is also a bundled approach to improving outcome. Without a mechanistic outcome, it will be difficult to tell where an improvement in outcome is exactly being derived from. However, we find this less important than the actual improvement in outcome.

The LOV-ED trial could be a pivotal study in changing how mechanical ventilation is used in the ED. We hope that this is a step forward in the study and care of critically ill mechanically ventilated patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Karen Steger-May, MA, from the Division of Biostatistics, Washington University in St Louis, for assistance with statistical planning and analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: BMF was involved in conception and study design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript; NMM and RSH were involved in study design, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript; IF was involved in conception and study design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript; RJS was involved in acquisition of data, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript; CCB and AAK were involved in acquisition of data, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript; MHK was involved in conception and study design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors have read and given final approval of the submitted manuscript.

Funding: BMF was funded by the KL2 Career Development Award, and this research was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences (Grants UL1 TR000448 and KL2 TR000450) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). BMF was also funded by the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital Clinical and Translational Sciences Research Program (Grant # 8041-88). NMM was supported by grant funds from the Emergency Medicine Foundation and the Health Resources and Services Administration. RJS was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) programme of the NCATS of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Numbers UL1 TR000448 and TL1 TR000449. CCB was supported by the Short-Term Institutional Research Training Grant, NIH T35 (NHLBI). RSH was supported by NIH grants R01 GM44118-22 and R01 GM09839. MHK was supported by the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation.

Disclaimer: Funders played no role (nor will they in the future) in the following features of the trial: study design, data collection, data management, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval: The study protocol received ethical approval by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University in St Louis School of Medicine (Institutional Review Board identification number 201409024) prior to beginning the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: On study completion, de-identified data will be made accessible through standard university repository policy.

References

- 1.Boyer AF, Schoenberg N, Babcock H et al. A prospective evaluation of ventilator-associated conditions and infection-related ventilator-associated conditions. Chest 2015;147:68–81. 10.1378/chest.14-0544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuller BM, Mohr NM, Drewry AM et al. Lower tidal volume at initiation of mechanical ventilation may reduce progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome-a systematic review. Crit Care 2013;17:R11 10.1186/cc11936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1685–93. 10.1056/NEJMoa050333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Easter BD, Fischer C, Fisher J. The use of mechanical ventilation in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:1183–8. 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreyfuss D, Soler P, Basset G et al. High inflation pressure pulmonary edema: respective effects of high airway pressure, high tidal volume, and positive end-expiratory pressure. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988;137:1159–64. 10.1164/ajrccm/137.5.1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webb HH, Tierney DF. Experimental pulmonary edema due to intermittent positive pressure ventilation with high inflation pressures. Protection by positive end-expiratory pressure. Am Rev Respir Dis 1974;110:556–65. 10.1164/arrd.1974.110.5.556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.No authors listed]. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1301–8. 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Determann RM, Royakkers A, Wolthuis EK et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with conventional tidal volumes for patients without acute lung injury: a preventive randomized controlled trial. Crit Care 2010;14:R1 10.1186/cc8230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serpa Neto A, Cardoso SO, Manetta JA et al. Association between use of lung-protective ventilation with lower tidal volumes and clinical outcomes among patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;308:1651–9. 10.1001/jama.2012.13730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Futier E, Constantin JM, Paugam-Burtz C et al. A trial of intraoperative low-tidal-volume ventilation in abdominal surgery. N Engl J Med 2013;369:428–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1301082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gajic O, Dara SI, Mendez JL et al. Ventilator-associated lung injury in patients without acute lung injury at the onset of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2004;32:1817–24. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000133019.52531.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gajic O, Frutos-Vivar F, Esteban A et al. Ventilator settings as a risk factor for acute respiratory distress syndrome in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med 2005;31:922–6. 10.1007/s00134-005-2625-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia X, Malhotra A, Saeed M et al. Risk factors for ARDS in patients receiving mechanical ventilation for > 48 h*. Chest 2008;133:853–61. 10.1378/chest.07-1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yilmaz M, Keegan MT, Iscimen R et al. Toward the prevention of acute lung injury: protocol-guided limitation of large tidal volume ventilation and inappropriate transfusion*. Crit Care Med 2007;35:1660–6; quiz 1667 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269037.66955.F0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mascia L, Zavala E, Bosma K et al. High tidal volume is associated with the development of acute lung injury after severe brain injury: an international observational study*. Crit Care Med 2007;35:1815–20. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000275269.77467.DF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasero DDA, Guerriero F, Rana N et al. High tidal volume as an independent risk factor for acute lung injury after cardiac surgery. Intensive Care Med 2008;34(Suppl1):0398. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuller BM, Mohr NM, Dettmer M et al. Mechanical ventilation and acute lung injury in emergency department patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: an observational study. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:659–69. PMCID: PMC3718493 10.1111/acem.12167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuller BM, Mohr NM, Miller CN et al. Mechanical ventilation and acute respiratory distress syndrome in the emergency department: a multi-center, observational, prospective, cross-sectional, study. Chest 2015;148:365–74. 10.1378/chest.14-2476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dettmer MR, Mohr NM, Fuller BM. Sepsis-associated pulmonary complications in emergency department patients monitored with serial lactate: an observational cohort study. J Crit Care 2015;30:1163–8. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.07.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahn JM, Andersson L, Karir V et al. Low tidal volume ventilation does not increase sedation use in patients with acute lung injury*. Crit Care Med 2005;33:766–71. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000157786.41506.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kilickaya O, Gajic O. Initial ventilator settings for critically ill patients. Crit Care 2013;17:123 10.1186/cc12516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolthuis EK, Veelo DP, Choi G et al. Mechanical ventilation with lower tidal volumes does not influence the prescription of opioids or sedatives. Crit Care 2007;11:R77 10.1186/cc5969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong MN, Ferguson ND. Lung-protective ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. How soon is now? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:125–6. 10.1164/rccm.201412-2250ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT et al. , The ARDS definition task force. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA 2012;307:2526–33. 10.1001/jama.2012.5669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gajic O, Dabbagh O, Park PK et al. Early identification of patients at risk of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:462–70. 10.1164/rccm.201004-0549OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L et al. The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:1573–82. 10.1007/s00134-012-2682-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Society of Critical Care Medicine and The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Sepsis without walls: ensuring all patients receive optimal, time-sensitive care. Baltimore, Maryland, USA: 25 September 2015. Live Event. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herring AA, Ginde AA, Fahimi J et al. Increasing critical care admissions from US emergency departments, 2001–2009*. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1197–204. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c086f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Needham DM, Bronskill SE, Calinawan JR et al. Projected incidence of mechanical ventilation in Ontario to 2026: preparing for the aging baby boomers*. Crit Care Med 2005;33:574–9. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000155992.21174.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hung SC, Kung CT, Hung CW et al. Determining delayed admission to intensive care unit for mechanically ventilated patients in the emergency department. Crit Care 2014;18:485 10.1186/s13054-014-0485-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Needham DM, Yang T, Dinglas VD et al. Timing of low tidal volume ventilation and intensive care unit mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome. A Prospective Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:177–85. 10.1164/rccm.201409-1598OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Needham DM, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA et al. Lung protective mechanical ventilation and two year survival in patients with acute lung injury: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones AE, Kline JA. Use of goal-directed therapy for severe sepsis and septic shock in academic emergency departments. Crit Care Med 2005;33:1888–9. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000166872.78449.B1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010991supp.pdf (313KB, pdf)