Abstract

Objectives

Smoking cessation services can help smokers to quit; however, many smoking relapse cases occur over time. Initial relapse prevention should play an important role in achieving the goal of long-term smoking cessation. Several studies have focused on the effect of extended telephone support in relapse prevention, but the conclusions remain conflicting.

Design and setting

From October 2008 to August 2013, a longitudinal, controlled study was performed in a large general hospital of Beijing.

Participants

The smokers who sought treatment at our smoking cessation clinic were non-randomised and divided into 2 groups: face-to-face individual counselling group (FC group), and face-to-face individual counselling plus telephone follow-up counselling group (FCF group). No pharmacotherapy was offered.

Outcomes

The timing of initial smoking relapse was compared between FC and FCF groups. Predictors of initial relapse were investigated during the first 180 days, using the Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

Of 547 eligible male smokers who volunteered to participate, 457 participants (117 in FC group and 340 in FCF group) achieved at least 24 h abstinence. The majority of the lapse episodes occurred during the first 2 weeks after the quit date. Smokers who did not receive the follow-up telephone counselling (FC group) tended to relapse to smoking earlier than those smokers who received the additional follow-up telephone counselling (FCF group), and the log-rank test was statistically significant (p=0.003). A Cox regression model showed that, in the FCF group, being married, and having a lower Fagerström test score, normal body mass index and doctor-diagnosed tobacco-related chronic diseases, were significantly independent protective predictors of smoking relapse.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that additional follow-up telephone counselling might be an effective strategy in preventing relapse. Further research is still needed to confirm our findings.

Keywords: additional follow-up telephone counselling, initial smoking relapse, predictor of relapse, Chinese male smoker

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This longitudinal, controlled study contributes to the limited knowledge of the efficacy of additional follow-up telephone counselling sessions on smoking relapse prevention among Chinese male smokers.

Smokers who did not receive the follow-up telephone counselling tended to relapse to smoking significantly earlier than those smokers who received the additional follow-up telephone counselling.

Given the nature of the intervention, it is impossible to blind the counsellors during the follow-up telephone sessions; thus, socially desirable responses may have been given.

This study involves the recall of the exact date of initial smoking relapse, and thus recall bias cannot be avoided.

Within the limitations of the present study, further research is still needed to confirm our findings.

Introduction

Tobacco consumption remains the leading challenge of global public health, especially in Mainland China. Smoking cessation services can help smokers to quit, however, many smoking relapse cases occur over time. A study performed by Osler et al1 reported that 70–90% of smokers who attempted to quit smoking eventually relapse to smoking within 1 year. Yang et al2 investigated 122 220 Chinese participants and reported that about 12% of current Chinese smokers had quit at least once, but relapsed by the end of the survey. The majority of relapse cases occur during the initial days of quitting.3 Most of those quitters who have experienced an early initial lapse eventually progressed to full relapse.4 Thus, initial relapse prevention should play an important role in achieving the goal of long-term smoking cessation.

Previous studies have reported that supportive telephone counselling might be a possible approach to sustain abstinence.5–7 Telephone follow-up counselling can extend contact after baseline treatment. By teaching skills to cope with temptations of smoking relapse, the extended telephone support might have a positive effect on the continuous success among those smokers who have achieved abstinence from smoking. Several studies have focused on the effect of extended telephone support in relapse prevention, but the conclusions remain conflicting.8–11 One reason is that the complexity of the relapse may differ across different populations and races. Additionally, different studies used a variety of intervention methods, which might also affect the results.

Previous studies have addressed predictors of smoking relapse. Nicotine dependence,12–15 younger age,10 14 16 17 lower income,10 18 social smoking cues,10 12 14 depression symptom13 19 20 and lower abstinence self-efficacy15 19 20 were the most commonly reported predictors of smoking relapse. It is worth noting that all of the above studies were performed in developed Western countries. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the effect of additional follow-up telephone counselling on initial smoking relapse prevention and identified predictors of smoking relapse among Chinese male smokers.

Chinese smokers constitute one-third of the world's smokers. Therefore, smoking cessation in China should play a critical role in reducing the disease burden of tobacco use worldwide. Thus, we conducted the present study to explore the impact of additional telephone follow-up sessions on relapse prevention among smokers who voluntarily sought treatment to a smoking cessation clinic (SCC) in Beijing, China. We hypothesised that the additional telephone follow-up counselling was an effective method to prevent relapse by offering additional support. We conducted Cox regression analysis to further explore the predictors of smoking relapse during the 6 months follow-up period, based on a longitudinal, controlled study.

Methods

This was a post hoc analysis based on a retrospective, non-randomised study, which has been previously reported.21 In brief, we established a SCC in the outpatient department of the People's Liberation Army General Hospital in Beijing, China. The participants were current smokers who voluntarily sought treatment at the SCC.

We included current smokers who smoked at least one cigarette daily for at least 6 months at baseline. Each current smoker (aged 18 years or older) who agreed to participant in our study was asked to sign an informed consent form (the data were used only for scientific research).

Participant recruitment and intervention

We divided all eligible smokers who voluntarily sought treatment from our SCC into two groups: (1) face-to-face individual counselling group (FC group) and (2) face-to-face individual counselling plus follow-up telephone counselling group (FCF group). Each smoker received the same intervention treatment in his or her first visit. No pharmacotherapy was offered. The information about how smokers were divided into these two groups is listed below.

At the first visit, sociodemographic and tobacco-related information of each participant was assessed using a baseline questionnaire in a face-to-face interview. A trained physician then provided individual counselling (lasting for more than 30 min) based on Prochaska's transtheoretical model and on the ‘five A's’.22 Each smoker was provided advice on strategies of overcoming psychological cravings, psychological dependence and social-cultural factors associated with tobacco dependency.23

After the baseline intervention, smokers who visited our clinic from October 2008 to December 2010 (n=254) participated in the telephone conversations at the 1-week, and 1-month, 3-month and 6-month follow-up. At each follow-up session, we conducted additional telephone counselling focused on relapse prevention to offer problem-oriented suggestions or advice. Trained counsellors also encouraged each participant to quit or to continue abstaining from smoking.

We could not perform a randomised controlled trial under real-world clinical conditions as randomly allocating the smokers into two groups with different follow-up interventions would have confused the smokers, as they sought a service and did not expect to be randomised. In studying the effect of the additional follow-up telephone counselling, we ceased the counselling for all of the smokers who first participated in 2011. These smokers were given the same follow-up telephone assessment at 1-week, and 1-month, 3-month and 6-month follow-up; however, no further additional telephone counselling was given. These smokers constituted the FC group (n=149).

After 2011, we resumed the additional follow-up telephone counselling sessions for all of the smokers. Smokers participating from February 2012 to August 2013 (n=144) and those participating from October 2008 to December 2010 formed the FCF group (n=398 in total).

Data collection

Baseline sociodemographic and tobacco-related factors

We collected sociodemographic and tobacco-related information of each eligible participant at the first visit. Baseline demographic data included age, gender, educational level, marital status, occupation and monthly family income. Tobacco-related questions included smoking history, smoking status, readiness to quit smoking, smoking destinations, cessation history, cessation motivations, doctor-diagnosed tobacco-related chronic diseases, alcohol use and self-efficacy (perceived confidence, importance and difficulties associated with quitting).

Exhaled carbon monoxide level was measured following a standard protocol and a Micro CO Smokerlizer.23 Body height and body weight were measured in indoor clothing without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight divided by the square of body height. Waist circumference was measured at the girth midway between lower rib margins.

Follow-up

To analyse the exact smoking or quitting status of each smoker, we designed a telephone follow-up questionnaire. The exact date of each smoking relapse episode was recorded in detail by trained counsellors at 1-week, and 1-month, 3-month and 6-month follow-up. All these data were determined from self-report by each participant via telephone.

Definitions

Quitters were those who achieved a minimum of 24 h abstinence after the baseline treatment.24 25 After achieving 24 h of abstinence, any subsequent smoking episode (even a puff) was defined as a smoking relapse. The date of an initial lapse after the first treatment was counted as the date of smoking relapse.25

Questions related to self-efficacy (perceived confidence, importance and difficulties associated with quitting) were measured based on the question: ‘How confident are you, or how important/difficult is it for you, to quit smoking?’, and the three answer choices were scored based on a scale of 1–100, denoting least to most. Nicotine dependence level was assessed using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), and the dependence level of each smoker was classified as low (0–3), moderate (4–5) or severe (6–10).26 Central obesity was defined as a waist circumference ≥90 cm for males, and ≥80 cm for females. Overweight or obese was defined as a BMI ≥23.0 kg/m2.27

Statistical analysis

The data were entered (double entry) using Epidata (V.3.1) and analysed using SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA) for Windows (19.0). All p values were two sided, and the level of statistical significance was set at a value of 0.05.

The baseline characteristics were performed by descriptive statistics. The t test and χ2 test were used to assess differences in the continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier technique and log-rank test were used to compare the timing of relapse between the two groups. Predictors of relapse were investigated during the first 180 days, using the Cox proportional hazards model (Cox regression). The HRs and 95% CIs were provided to assess the association between potential variables and initial smoking relapse.

Results

From 22 October 2008 to 31 August 2013, the baseline sample included a total of 570 smokers (547 males and 23 females). An absolutely higher proportion of males (96.0%) than females (4.0%) were included in the present study. Male smokers had different characteristics from females, and thus the present analysis included only 547 eligible male smokers (149 in the FC group and 398 in the FCF group). Among these males, 36 smokers (11 in the FC group and 25 in the FCF group) did not achieve 24 h abstinence status, and 54 smokers (21 in the FC group and 33 in the FCF group) were not contactable to record their initial lapse episode. The retention rates at the 1-week, and 1-month, 3-month and 6-month follow-up, were 94.9%, 92.8%, 91.0% and 89.4%, respectively. Finally, 457 male smokers were included in the present analysis, of which 117 were from the FC group and 340 from the FCF group.

Demographic and tobacco-related characteristics and other factors

As shown in table 1, the present study examined 457 male smokers. The mean age of the smokers was 41.1 years, with a SD of 10.9. There were no significant differences among the two groups, except that the smokers in the FCF group perceived less difficulty in quitting. Most of the smokers were married (87.7%), had higher educational level (60.2%), were currently employed (80.5%) and had medium or higher nicotine dependence level at baseline (68.9%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and tobacco-related factors of 457 male smokers in two groups

| FC (N=117) | FCF (N=340) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) Mean (SD) |

41.2 (10.0) | 41.0 (11.2) | 0.865 |

| Age (years) Number (%) |

N (%) | N (%) | |

| <31 | 16 (13.7) | 64 (18.8) | 0.123 |

| 31 to 40 | 36 (30.8) | 113 (33.2) | |

| 41 to 50 | 46 (39.3) | 95 (27.9) | |

| >50 | 19 (16.2) | 68 (20.0) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 104 (88.9) | 297 (87.4) | 0.662 |

| Single or divorced | 13 (11.1) | 43 (12.6) | |

| Educational level | |||

| College and above | 74 (63.2) | 201 (59.1) | 0.431 |

| High school and below | 43 (36.8) | 139 (40.9) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Currently employed | 91 (77.8) | 277 (81.5) | 0.384 |

| Student/unemployed/retired/others | 26 (22.2) | 63 (18.5) | |

| Family income per month (Yuan, US$1=¥6) | |||

| <3000 | 43 (36.8) | 123 (36.2) | 0.955 |

| 3000 to 6000 | 31 (26.5) | 95 (27.9) | |

| >6000 | 43 (36.8) | 122 (35.9) | |

| Tobacco-related factors | |||

| Age at initiation of smoking (years) | |||

| <18 | 40 (34.2) | 113 (33.2) | 0.851 |

| ≥18 | 77 (65.8) | 227 (66.8) | |

| Cigarettes smoked on average daily (cig/day) | |||

| ≥20 | 74 (63.2) | 201 (59.1) | 0.711 |

| 10 to 19 | 33 (28.2) | 104 (30.6) | |

| <10 | 10 (8.5) | 35 (10.3) | |

| Smoking duration (years) | |||

| <20 | 46 (39.3) | 153 (45.0) | 0.285 |

| ≥20 | 71 (60.7) | 187 (55.0) | |

| Prior attempts to quit smoking | |||

| 0 | 27 (23.1) | 84 (24.7) | 0.723 |

| ≥1 | 90 (76.9) | 256 (75.3) | |

| Fagerström test score | |||

| Severe (6–10) | 53 (45.3) | 148 (43.5) | 0.569 |

| Moderate (4–5) | 32 (27.4) | 82 (24.1) | |

| Low (0–3) | 32 (27.4) | 110 (32.4) | |

| Exhaled CO level at first visit (mean:12 ppm) | |||

| ≥12 | 60 (51.3) | 164 (48.2) | 0.570 |

| <12 | 57 (48.7) | 176 (51.8) | |

| Stage of quitting smoking | |||

| Contemplation | 33 (28.2) | 76 (22.4) | 0.415 |

| Preparation | 40 (34.2) | 120 (35.3) | |

| Action | 44 (37.6) | 144 (42.4) | |

| Perceived importance of quitting (mean score: 86) | |||

| <86 | 47 (40.2) | 139 (40.9) | 0.893 |

| ≥86 | 70 (59.8) | 201 (59.1) | |

| Perceived difficulty in quitting (mean score: 73) | |||

| ≥73 | 87 (74.4) | 179 (52.6) | <0.001 |

| <73 | 30 (25.6) | 161 (47.4) | |

| Perceived confidence in quitting (mean score: 67) | |||

| <67 | 52 (44.4) | 158 (46.5) | 0.704 |

| ≥67 | 65 (55.6) | 182 (53.5) | |

| Expenditure on cigarettes per day, Yuan (mean: 20) | |||

| <20 | 61 (52.1) | 156 (45.9) | 0.243 |

| ≥20 | 56 (47.9) | 184 (54.1) | |

| Perceived health status at the first visit | |||

| Fair/poor/very poor | 73 (62.4) | 232 (68.2) | 0.247 |

| Very good/good | 44 (37.6) | 108 (31.8) | |

| Number of other smokers in household | |||

| 0 | 98 (83.8) | 273 (80.3) | 0.408 |

| ≥1 | 19 (16.2) | 67 (19.7) | |

| Medical advice to quit | 36 (30.8) | 123 (36.2) | 0.290 |

| Doctor-diagnosed tobacco-related chronic diseases | 62 (53.0) | 183 (53.8) | 0.876 |

| Current drinkers | 82 (70.1) | 228 (67.1) | 0.545 |

| Central obese | 68 (58.1) | 230 (67.6) | 0.062 |

| Overweight/obese | 86 (73.5) | 264 (77.6) | 0.361 |

FC group, face-to-face counselling only; FCF group, face-to-face counselling plus follow-up telephone counselling.

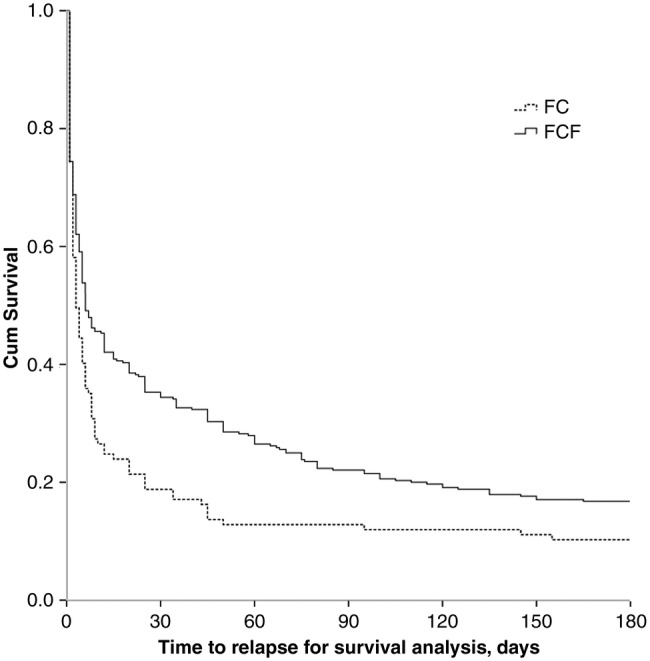

Initial lapse episodes and relapse curve

Of the 457 smokers who successfully achieved 24 h of abstinence, 69 smokers achieved 180 days continuous cessation status. The 180 days continuous abstinence rate was 10.3% in the FC group, lower than that in the FCF group (16.8%), and the difference was borderline significant (p=0.09). Most of the lapse episodes occurred during the first 2 weeks after the quit date, during which the survival rate quickly decreased from 100% to 24.8% in the FC group, and 100% to 39.1% in the FCF group. Figure 1 presents data showing that the smokers who did not receive follow-up telephone counselling (FC group) tended to relapse to smoking earlier than those smokers who received the additional follow-up telephone counselling (FCF group), and the log-rank test was statistically significant (p=0.003).

Figure 1.

Relapse curve of smokers in the two groups. FCF group, face-to-face counselling plus follow-up telephone counselling; FC group, face-to-face counselling only.

Predictors of relapse

To diminish the confounding property of population differences, all factors in table 1 were entered into the Cox regression model, with the exception of cigarette consumption. As shown in table 2, the additional follow-up telephone counselling was a significantly independent protective predictor of smoking relapse. Other predictors associated with decreased risk of relapse included being married, a lower Fagerström test score, a normal BMI and doctor-diagnosed tobacco-related chronic diseases.

Table 2.

Predictors of smoking relapse at 180 days

| Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | p Value | p For trend | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||

| FC | 1.00 | ||

| FCF | 0.73 (0.58 to 0.93) | 0.009 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 1.00 | ||

| Single or divorced | 1.65 (1.16 to 2.34) | 0.005 | |

| Fagerström test score | |||

| Severe (6–10) | 1.00 | 0.003 | |

| Moderate (4–5) | 0.80 (0.61 to 1.05) | 0.109 | |

| Low (0–3) | 0.64 (0.49 to 0.82) | 0.001 | |

| Doctor-diagnosed tobacco-related chronic diseases | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.72 (0.56 to 0.92) | 0.009 | |

| BMI | |||

| Normal | 1.00 | ||

| Overweight/obese | 1.38 (1.03 to 1.86) | 0.033 | |

*All factors in table 1 were entered into the model, with the exception of cigarette consumption.

BMI, body mass index; FC group, face-to-face counselling only; FCF group, face-to-face counselling plus follow-up telephone counselling.

Compared with smokers who did not receive the follow-up telephone counselling (FC group), the HR (95% CI) of those smokers who received the telephone follow-up counselling (FCF group) for smoking relapse was 0.73 (0.58 to 0.93), p=0.009. The Fagerström test score exhibited a negative dose–response relationship, where the HRs (95% CIs) of the moderate level and low level were 0.80 (0.61 to 1.05) and 0.64 (0.49 to 0.82), respectively. For single or divorced smokers versus those who were married, the HR (95% CI) for relapse was 1.65 (1.16 to 2.34). In smokers with tobacco-related chronic diseases, the HR (95% CI) for relapse was 0.72 (0.56 to 0.92), compared with that of healthy smokers. In smokers who were overweight or obese versus those smokers with normal BMI, the HR (95% CI) for relapse was 1.38 (1.03 to 1.86).

Discussion

Using systematically collected data, we found that the smokers who did not receive follow-up telephone counselling (FC group) tended to relapse to smoking earlier than those smokers who received the additional follow-up telephone counselling (FCF group). Being married, and having a lower Fagerström test score, a normal BMI and doctor-diagnosed tobacco-related chronic diseases, were also significantly independent protective predictors of smoking relapse.

In accordance with the results of previous studies, our results have demonstrated that the additional telephone follow-up counselling is an effective way to prevent smoking relapse, even after adjusting for potential confounding factors. A study by Cui et al10 reported that at least three postcessation follow-up calls actively decreased the relapse rate among veteran smokers. Yasin et al11 reported that participants who attended three sessions had a lower likelihood of relapse after 6 months follow-up. Relapse rates, with no smoking cessation medications, appeared to be a bit higher compared with the reports aforementioned. Additionally, another reason for the higher relapse rates is that we set regular follow-up sessions at 1-week, and 1-month, 3-month and 6-month follow-up. Hence, more intensive telephone support delivered closer to the targeted quit date may be more effective in preventing smoking relapse.

A higher nicotine dependence level at baseline was a significantly independent predictor of smoking relapse, which is consistent with previous reports.12–14 Smokers with higher nicotine dependence level had more serious withdrawal symptoms, and thus relapsed earlier than those smokers with lower nicotine dependence level. Our results suggested that smokers who were counted as overweight or obese at baseline were more likely to relapse to smoking. Weight gain is a common phenomenon after quitting cigarettes.28 Smokers already overweight or obese at baseline might have concerns about weight gain after cessation, and thus may tend to more often relapse to smoking after short-term smoking cessation.12 However, body weight is a dynamic factor that changes over time. In consideration of the lack of detailed data of weight change after the baseline treatment, we could not assess the influence of body weight in the process of smoking cessation. Moreover, those smokers with normal weight at baseline might also have concerns about weight gain after stopping smoking. Therefore, the observed results of the present study were probably influenced by other undetected factors beyond concerns about weight gain. Further prospective studies are needed to authenticate the assumption regarding the relationship between weight status and relapse. We also detected that being married and having doctor-diagnosed tobacco-related chronic diseases were negatively related to smoking relapse. Smokers with tobacco-related chronic diseases may be concerned about their health status, and thus have a greater intention to quit smoking.29 Married smokers often receive support from their family members, and are thus more likely to maintain cessation status than are single smokers.30

Notably, there was a significant difference regarding perceived difficulty of quitting between the groups at baseline. After adjusting for confounding variables in the Cox model, this factor was not found to be a predictor of relapse in the present study, which indicates that other detected predictors might have a stronger relationship with smoking relapse than the variable of perceived difficulty of quitting. Additionally, the null association might result from the limited number of included smokers. Furthermore, we did not detect other predictors of smoking relapse reported in previous studies, such as higher frequency of smoking intention, younger age, a deficiency of willingness to quit smoking, lower social class, lower educational level and negative emotional state.15–20 Owing to the various population characteristics, different intervention methods and other undetected factors, results on predictors were often not totally consistent. For example, in China's current alcohol and tobacco culture, smokers are usually social entertained with drinking and smoking together. Besides, tobacco products are relatively cheaper in China than in developed Western countries. These social factors aforementioned might partially affect our findings. More research with larger sample size and more detailed data are warranted to detect more predictors associated with smoking relapse in China.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, smokers visiting the SCC were not assigned randomly. There was a significant difference regarding perceived difficulty of quitting between the groups at baseline. To avoid these potentially confounding factors, we adjusted all detected variables in the Cox proportional hazards model. However, differences between unmeasured covariates, or other dynamic factors (changed over time) may have affected the results of the present study. Second, because approximately 65% of the smokers resided outside of Beijing, it was not convenient for them to attend the face-to-face interviews. We invited all the participants who self-reported abstaining from smoking to attend a face-to-face interview for biochemical verification (exhaled carbon monoxide test). However, only approximately 9% of the smokers eventually came back to our SCC and underwent the test. As a result, we used the self-reported smoking status as the outcome measurement. Third, given the nature of the intervention, it was impossible to blind the counsellors during the follow-up telephone sessions. Furthermore, the counsellors delivering the follow-up telephone counselling were also responsible for collecting the outcome data. Therefore, socially desirable responses could not be avoided. Actually, our counsellors were not informed of the objectives of the research as a whole, in order to record tobacco use status with minimal subjective bias. Lastly, this study involved recall of the exact date of initial smoking relapse, and thus recall bias might have existed. The smoking relapse process is dynamic, and the full process of smoking relapse may not be exactly recalled by each participant, and not be fully recorded by the counsellors. To avoid bias, we only recorded the initial relapse episode of each participant after the baseline treatment, which might be more impressive than other relapse episodes.

Within the limitations of this longitudinal, non-randomised, controlled study, it can be concluded that additional follow-up telephone counselling might be an effective method in preventing further relapse. Further research is required to identify effective methods to help individuals with high risk of smoking relapse.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Li Xiao, Jinghong Zhu and Jing Feng for their research assistance with the follow-up interview; Tai-hing Lam and Sophia SC Chan contributed to the establishment of the clinic and design of the interventions and provided training.

Footnotes

Contributors: LW and YH designed the study and analysed the data. BJ, FZ, QL, CZ and LZ helped with data collection and field operations. LW wrote the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, 81373080; Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission, Z121107001012070; Clinical Research Grants of Chinese PLA General Hospital, 2013FC-TSYS-1021, MJ201447.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Independent Ethics Committee of the Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital (S2013-066-01).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data on the quality appraisal of the included studies are available by emailing wlyg0118@163.com.

References

- 1.Osler M, Prescott E, Godtfredsen N et al. . Gender and determinants of smoking cessation: a longitudinal study. Prev Med 1999;29:57–62. 10.1006/pmed.1999.0510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang G, Ma J, Chen A et al. . Smoking cessation in China: findings from the 1996 national prevalence survey. Tob Control 2001;10:170–4. 10.1136/tc.10.2.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 2004;99:29–38. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiffman S, Hickcox M, Paty JA et al. . Progression from a smoking lapse to relapse: prediction from abstinence violation effects, nicotine dependence, and lapse characteristics. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:993–1002. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajek P, Stead LF, West R et al. . Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;8:CD003999 10.1002/14651858.CD003999.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Perera R et al. . Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;8:CD002850 10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lando HA, Pirie PL, Roski J et al. . Promoting abstinence among relapsed chronic smokers: the effect of telephone support. Am J Public Health 1996;86:1786–90. 10.2105/AJPH.86.12.1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandon TH, Collins BN, Juliano LM et al. . Preventing relapse among former smokers: a comparison of minimal interventions through telephone and mail. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68:103–13. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segan CJ, Borland R. Does extended telephone callback counselling prevent smoking relapse? Health Educ Res 2011;26:336–47. 10.1093/her/cyr009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui Y, Wen W, Moriarty CJ et al. . Risk factors and their effects on the dynamic process of smoking relapse among veteran smokers. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:967–81. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yasin SM, Moy FM, Retneswari M et al. . Timing and risk factors associated with relapse among smokers attempting to quit in Malaysia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2012;16:980–5. 10.5588/ijtld.11.0748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou X, Nonnemaker J, Sherrill B et al. . Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addict Behav 2009;34:365–73. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Killen JD, Fortmann SP, Kraemer HC et al. . Interactive effects of depression symptoms, nicotine dependence, and weight change on late smoking relapse. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:1060–7. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Mhamdi S, Sriha A, Bouanene I et al. . Predictors of smoking relapse in a cohort of adolescents and young adults in Monastir (Tunisia). Tob Induc Dis 2013;11:12 10.1186/1617-9625-11-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herd N, Borland R, Hyland A. Predictors of smoking relapse by duration of abstinence: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction 2009;104:2088–99. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02732.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura M, Oshima A, Ohkura M et al. . Predictors of lapse and relapse to smoking in successful quitters in a varenicline post hoc analysis in Japanese smokers. Clin Ther 2014;36:918–27. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salive ME, Cornoni-Huntley J, LaCroix AZ et al. . Predictors of smoking cessation and relapse in older adults. Am J Public Health 1992;82:1268–71. 10.2105/AJPH.82.9.1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernández E, Schiaffino A, Borrell C et al. . Social class, education, and smoking cessation: long-term follow-up of patients treated at a smoking cessation unit. Nicotine Tob Res 2006;8:29–36. 10.1080/14622200500264432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gökbayrak NS, Paiva AL, Blissmer BJ et al. . Predictors of relapse among smokers: transtheoretical effort variables, demographics, and smoking severity. Addict Behav 2015;42:176–9. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vangeli E, Stapleton J, West R. Smoking intentions and mood preceding lapse after completion of treatment to aid smoking cessation. Patient Educ Couns 2010;81:267–71. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu L, He Y, Jiang B et al. . Relationship between education levels and booster counselling sessions on smoking cessation among Chinese smokers. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007885 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prochaska JO, Goldstein MG. Process of smoking cessation. Implications for clinicians. Clin Chest Med 1991;12:727–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdullah AS, Hedley AJ, Chan SS et al. , Hong Kong council on smoking and health Smoking Cessation Health Centre (SCHC) steering group. Establishment and evaluation of a smoking cessation clinic in Hong Kong: a model for the future service provider. J Public Health (Oxf) 2004;26:239–44. 10.1093/pubmed/fdh147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hufford MR, Witkiewitz K, Shields AL et al. . Relapse as a nonlinear dynamic system: application to patients with alcohol use disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 2003;112: 219–27. 10.1037/0021-843X.112.2.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abrantes AM, Strong DR, Lejuez CW et al. . The role of negative affect in risk for early lapse among low distress tolerance smokers. Addict Behav 2008;33:1394–401. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fagerström KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav 1978;3:235–41. 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series 894 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aubin H-J, Farley A, Lycett D et al. . Weight gain in smokers after quitting cigarettes: meta-analysis. BMJ 2012;345:e4439 10.1136/bmj.e4439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azevedo RC, Fernandes RF. Factors relating to failure to quit smoking: a prospective cohort study. Sao Paulo Med J 2011;129:380–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wenig JR, Erfurt L, Kröger CB et al. . Smoking cessation in groups-who benefits in the long term? Health Educ Res 2013;28:869–88. 10.1093/her/cyt086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]