Abstract

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) has crucial roles in fatty acid metabolism and is an attractive target for drug discovery against diabetes, cancer and other diseases1–6. Saccharomyces cerevisiae ACC (ScACC) is crucial for the production of very-long-chain fatty acids and the maintenance of the nuclear envelope7,8. ACC contains biotin carboxylase (BC) and carboxyltransferase (CT) activities, and its biotin is linked covalently to the biotin carboxyl carrier protein (BCCP). Most eukaryotic ACCs are 250 kD, multi-domain enzymes and function as homo-dimers and higher oligomers. They contain a unique, 80 kD central region that shares no homology with other proteins. While the structures of the BC, CT and BCCP domains and other biotin-dependent carboxylase holoenzymes are known1,9–14, currently there is no structural information on the ACC holoenzyme. Here we report the crystal structure of the full-length, 500 kD holoenzyme dimer of ScACC. The structure is strikingly different from those of the other biotin-dependent carboxylases. The central region contains five domains and is important for positioning the BC and CT domains for catalysis. The structure unexpectedly reveals a dimer of the BC domain and extensive conformational differences compared to the structure of BC domain alone, which is a monomer. These structural changes explain why the BC domain alone is catalytically inactive and define the molecular mechanism for the inhibition of eukaryotic ACC by the natural product soraphen A15,16 and by phosphorylation of a Ser residue just prior to the BC domain core in mammalian ACC. The BC and CT active sites are separated by 80 Å, and the entire BCCP domain must translocate during catalysis.

The primary sequences of the single-chain, multi-domain eukaryotic ACCs can be divided into three regions of roughly equal sizes. The N-terminal region (residues 1–795 in ScACC, Fig. 1a) contains the BC and BCCP domains, with possibly a BT (BC-CT interaction) domain between them, as observed in the structures of propionyl-CoA carboxylase (PCC)11 and 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase (MCC)12. The C-terminal region (residues 1492–2233) contains the N and C domains of CT17. The structure and function of the central region (residues 796–1491) are currently not known. It is not as well conserved among the eukaryotic ACCs (Extended Data Figs. 1–3). BC catalyzes the MgATP-dependent carboxylation of the N1′ atom of biotin (Extended Data Fig. 4). The carboxybiotin (and BCCP) then translocates to the CT active site, where the substrate acetyl-CoA is carboxylated.

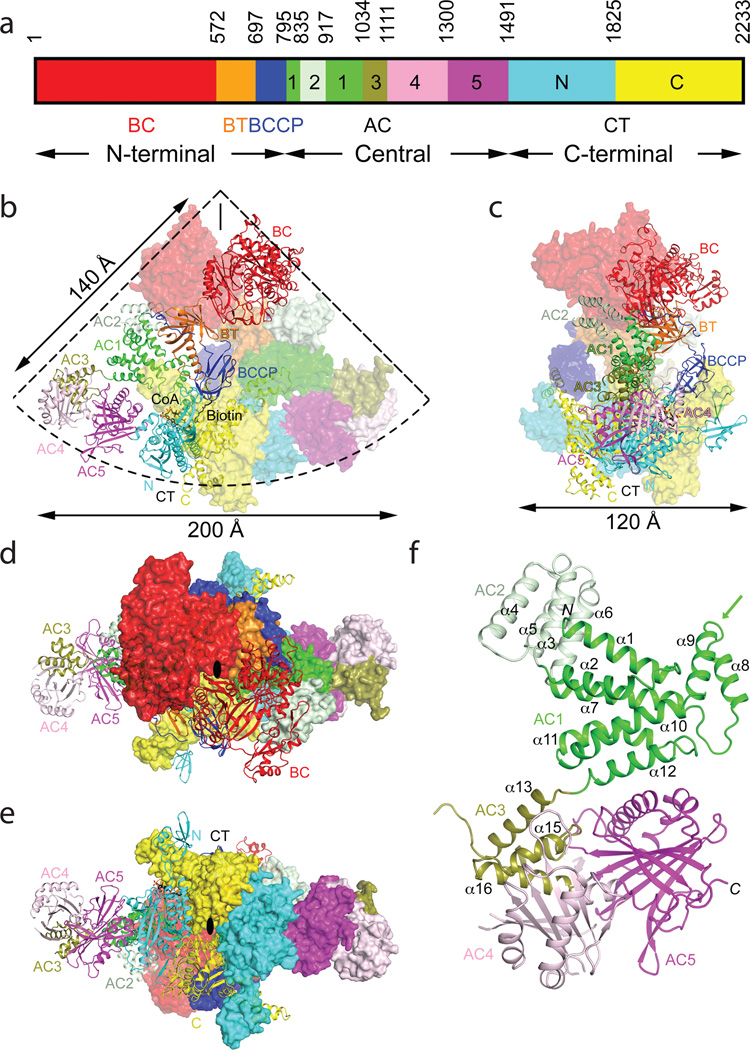

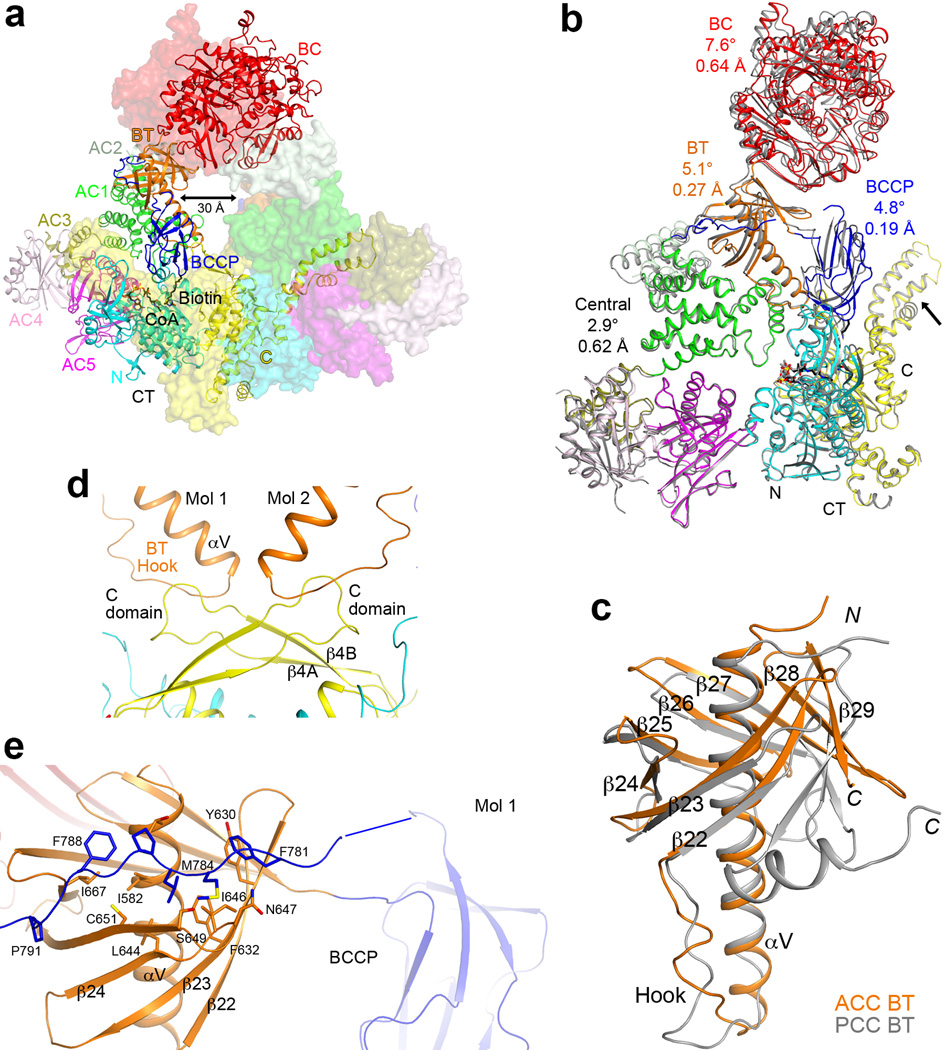

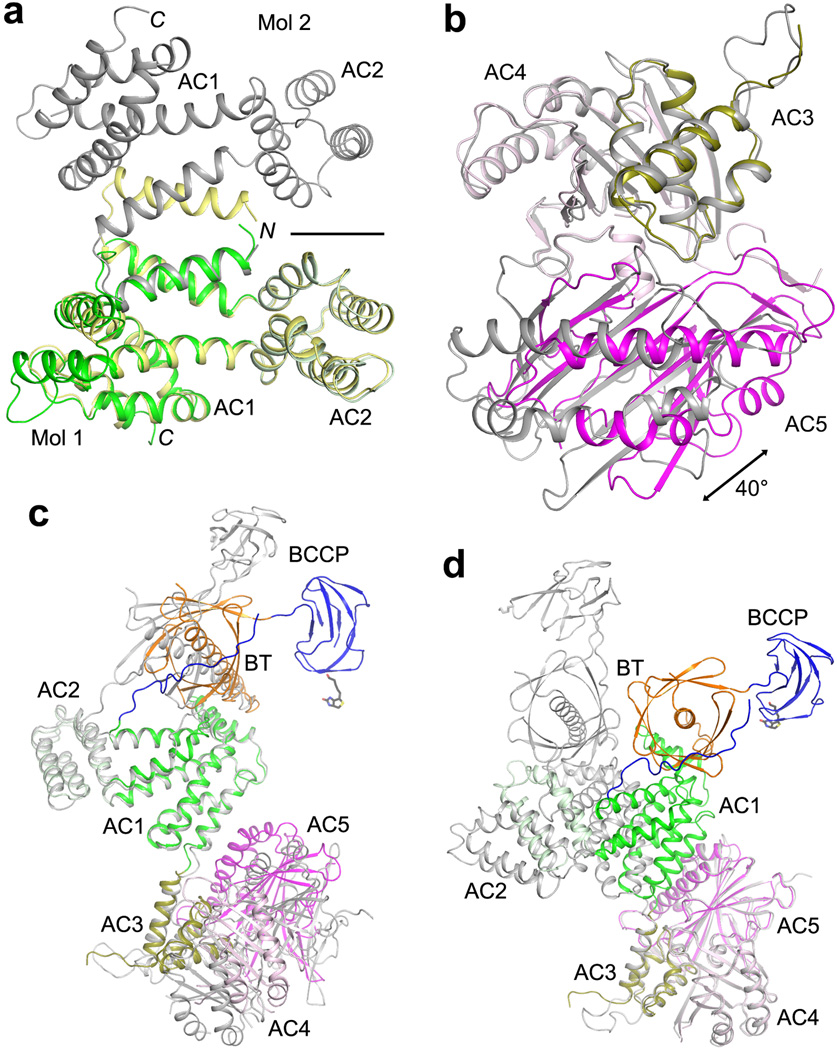

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of the 500 kD yeast acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ScACC) holoenzyme dimer. (a). Domain organization of ScACC. The three regions of the sequence are also indicated. AC: ACC central. (b). Overall structure of ScACC holoenzyme dimer. One protomer is shown as ribbons while the other is shown only as a surface for clarity, both colored according to panel a. The two-fold axis of the dimer is vertical (black line). Overall structure of ScACC holoenzyme, viewed from the side (c), down the BC domain dimer (d), and down the CT domain dimer (e). The two-fold axis is indicated with the black oval. (f). Structure of the five domains (AC1–5) in the central region of ScACC. The arrow points to the helical hairpin insert of AC1. The structure figures were produced with PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

We expressed in E. coli the 250 kD ScACC (residues 22–2233) and determined its crystal structure at 3.2 Å resolution (Extended Data Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 4). The structure of the ScACC holoenzyme is strikingly different from those of the other biotin-dependent carboxylases9–14. The 500 kD holoenzyme dimer obeys two-fold symmetry, and its overall structure is shaped like a quarter of a disk (Fig. 1b), with a radius of ~140 Å and thickness of ~120 Å (Fig. 1c), although there is a large channel measuring ~30 Å across through the center of the holoenzyme (Extended Data Fig. 5). A BC domain dimer (Fig. 1d) is located near the center of the disk, while the CT domain dimer (Fig. 1e) forms a part of the edge of the disk. A BCCP domain is positioned near the center of each face of the holoenzyme, and its biotin is located in the CT active site (Fig. 1b).

We have also determined the structure at 3.1 Å resolution of the holoenzyme where the BCCP domain is not biotinylated (Extended Data Table 1). The overall structure of this dimer is essentially the same as the other structure, with rms distance of 0.45 Å for their 3,928 equivalent Cα atoms, although the BCCP domain is disordered in the absence of biotinylation. Earlier studies showed that biotinylation stabilizes E. coli BCCP18,19. This structure of the holoenzyme will not be discussed further here.

The overall structures of the two protomers of the holoenzyme are similar, with rms distance of 1.1 Å for 1,862 equivalent Cα atoms located within 3 Å of each other after superposition. On the other hand, the rms distance is only 0.76 Å if the CT domains are superposed, and differences in the orientation and position of the other domains are visible, especially for the BC domain, which is located furthest from CT (Extended Data Fig. 4). Within CT, conformational differences in the small inserted domain17 are observed (Extended Data Fig. 5), likely linked to differences in the position of BCCP in the two protomers, as the insert domain has direct contacts with BCCP.

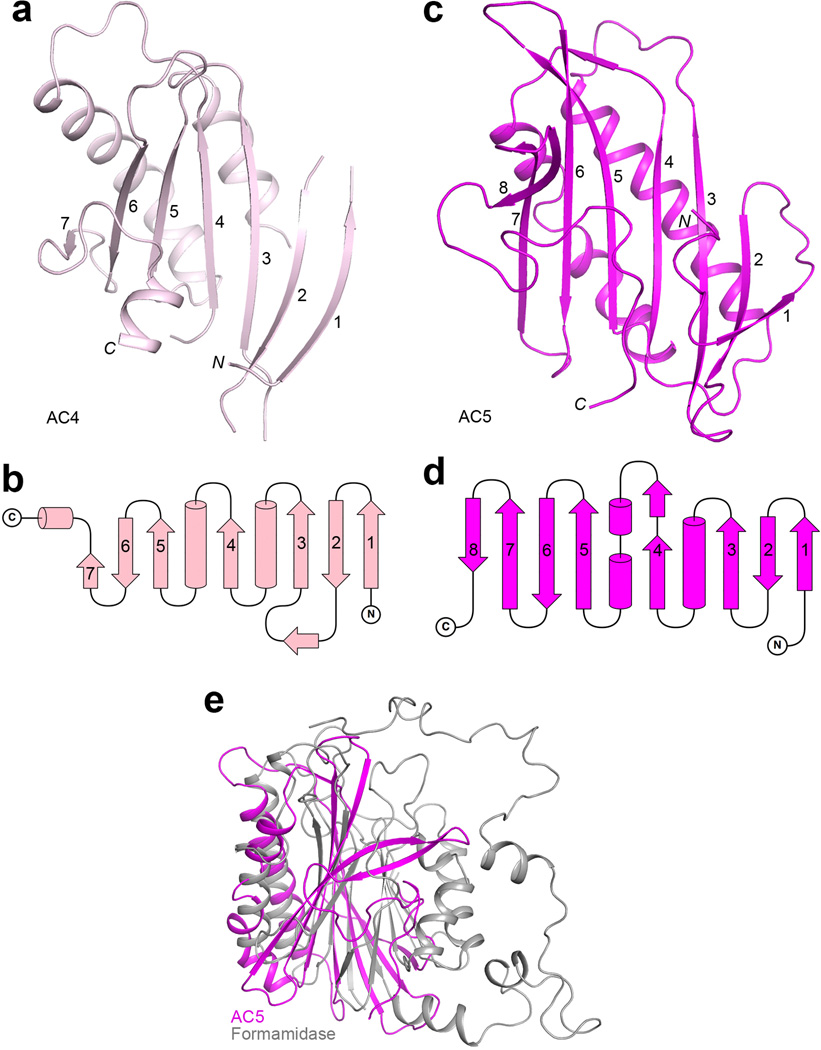

The structure reveals that the central region of ScACC contains five domains, which we have named ACC central (AC) domains AC1 through AC5, giving a total of 10 major domains for each ScACC protomer (Fig. 1a). Domains AC1, AC2 and AC3 are all helical (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 2). AC1 contains three pairs of anti-parallel helices as well as inserts of a four-helical bundle (domain AC2, helices α3–α6) and a helical hairpin (α8–α9, Extended Data Fig. 5). AC3 is also a four-helical bundle but it has no interactions with AC1 and AC2, and instead is positioned between AC4 and AC5, mediating interactions between them. Domain AC4 is located at the end of the disk edge, and is separated from the AC4 domain of the other protomer by ~200 Å (Fig. 1b). Unexpectedly, the structure shows that AC4 and AC5 have similar backbone folds, consisting of a twisted β-sheet flanked on one face by helices (Extended Data Figs. 4, 6). The rms distance is 2.9 Å for their equivalent Cα atoms, but the sequence identity is only 12%. This backbone fold has weak similarity to a part of formamidase20 (Extended Data Fig. 6) and several other enzymes, but the Z score is below 6.5 and the sequence identity is less than 9%21. The active sites of these enzymes are not conserved in AC4 or AC5. Therefore, this structural similarity is unlikely to have any functional significance for ACC.

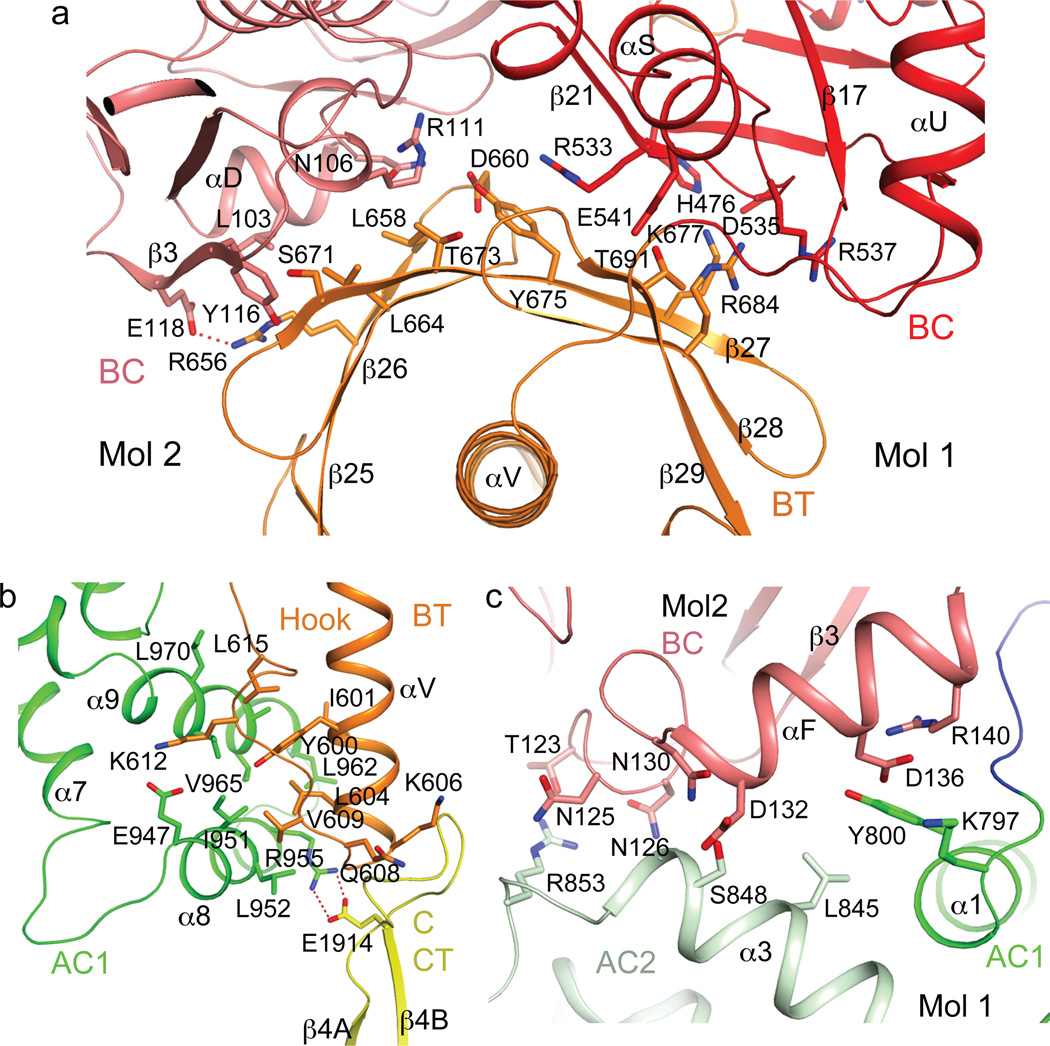

The structure confirms the presence of a BT domain in the N-terminal region of ScACC (Fig. 1a). Its structure is similar to that in PCC11, with a central, long helix (Extended Data Fig. 4) surrounded by an eight-stranded anti-parallel β-barrel (Extended Data Fig. 5). The domain helps to mediate interactions between the BC and CT domains, as there are no direct contacts between them in the holoenzyme (Fig. 1b). Within each protomer, the last three strands of the BT domain β-barrel (β27–β29) faces the BC domain (Figs. 1b, 2a), while the C-terminal end of the long helix and the following loop connecting to the first strand (the hook11) is flanked by the helical hairpin insert of AC1 (α8–α9) on one side and an inserted segment of a long loop between two β-strands (β4A and β4B) in the C domain of CT on the other side (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 4). In addition, a part of the long linker between the BCCP and AC1 domains has hydrophobic interactions with the top of one side of the BT domain β-barrel (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 5).

Figure 2.

Interactions among the domains in the ScACC holoenzyme. (a). The BT domain contacts the BC domain dimer. Side chains of residues in the interfaces between the BT domain (orange) and the BC domain of the same protomer (red) and the BC domain of the other protomer (salmon) are shown as stick models. (b). Interactions between the hook of the BT domain (orange) and the helical hairpin insert of AC1 domain (α8 and α9, green) and the β4A–β4B loop from the C domain of CT (yellow). (c). Interactions between domains AC1 (green) and AC2 (light green) of one protomer with the BC domain (salmon) of the other protomer.

A total of ~9,000 Å2 of the surface area of each protomer is buried in the dimer interface, predominantly from the BC (1,200 Å2, Extended Data Fig. 7) and CT (5,800 Å2, Extended Data Fig. 8) domain dimers. The BC domain contributes an additional 900 Å2 through contacts with the BT domain (500 Å2, Fig. 2a), AC1 (80 Å2) and AC2 (230 Å2, Fig. 2c) of the other protomer. The BCCP domain buries ~400 Å2 in the CT active site, where it contacts the C domain of the other protomer, but it is expected to translocate to the BC active site during catalysis (see below).

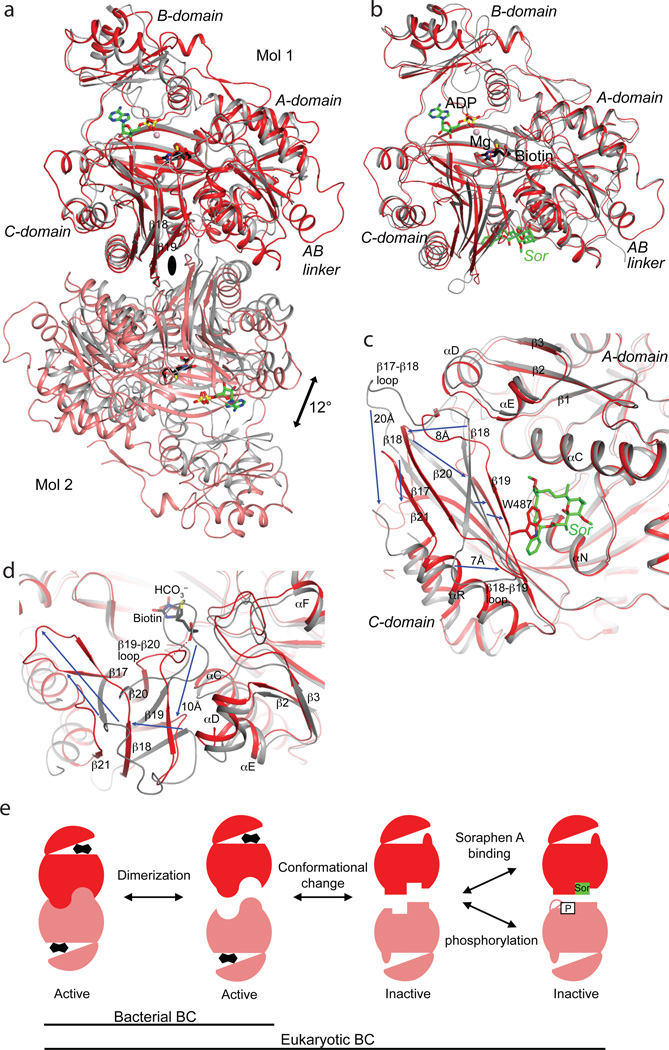

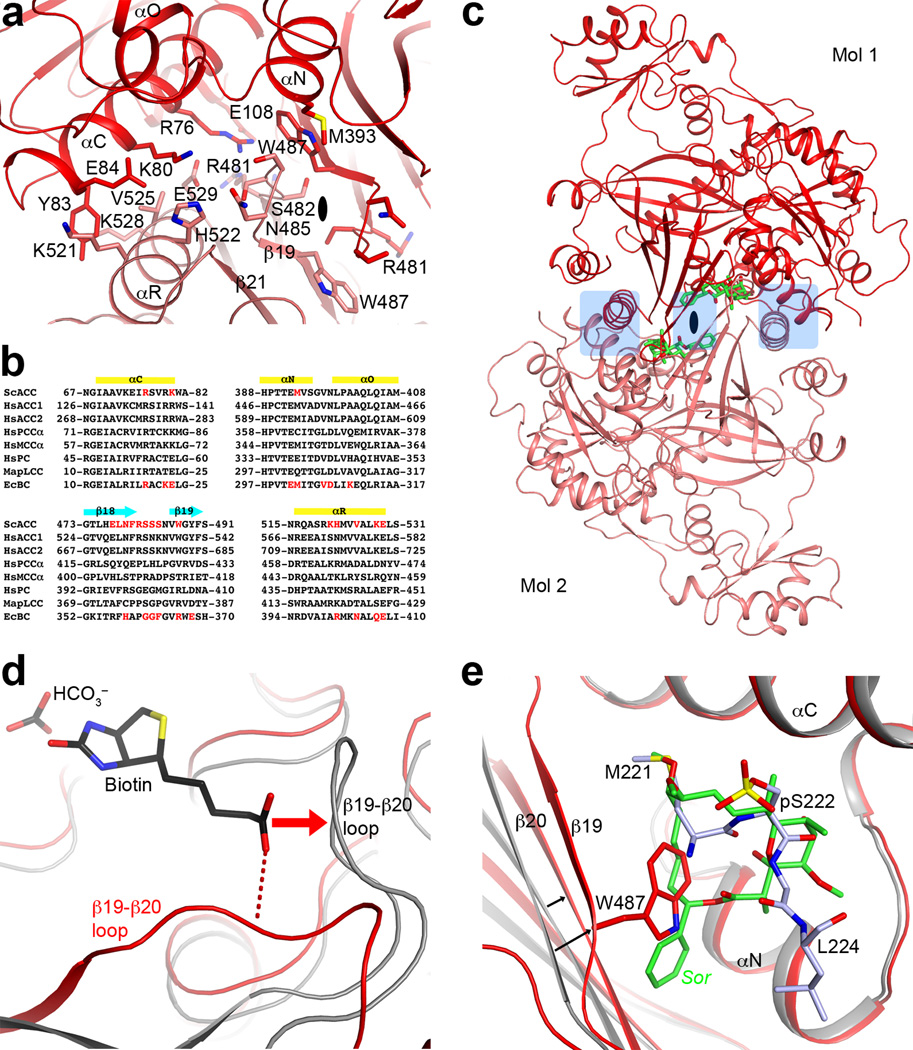

A major surprise from the structure is the observation of a BC domain dimer (Fig. 1d), because the BC domain alone is consistently a monomer and catalytically inactive based on earlier studies15,16,22,23. Moreover, the organization of this BC domain dimer is similar to that of the BC subunit dimer of E. coli ACC24–26 (Fig. 3a), with a mostly hydrophilic interface (Extended Data Fig. 7). However, the structure of BC domain alone is incompatible with such a dimer due to steric clashes between the two molecules16 (Extended Data Fig. 7). Large conformational changes for residues in the dimer interface are therefore necessary for the formation of this dimer, primarily involving the β-strands and connecting loops in the C sub-domain of BC (Fig. 3b). Especially, strand β18 moves by ~8 Å, taking it out of the central β-sheet of the C-domain (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Video 1). β18 instead forms a β-sheet with a new strand, β21, which is not present in the structure of BC domain alone. Residues in the β17–β18 loop move by up to 20 Å, and those in the β18–β19 loop by up to 7 Å (Fig. 3c). In addition, the main chain of neighboring strands β17, β19, and β20 shifts by ~3 Å. The new β18-loop-β19 structure is in the center of the BC domain dimer (Fig. 3a), where the tip of this loop contacts the side chain of Trp487 in the other protomer (Extended Data Fig. 7).

Figure 3.

A dimeric BC domain in the ScACC holoenzyme. (a). Overlay of the BC domain dimer of ScACC (in red and salmon) with the BC subunit dimer of E. coli ACC (gray) in complex with ADP (green), bicarbonate (black), biotin (black), and Mg2+ (pink sphere)26. The two molecules at the top are superposed, and the two molecules at the bottom have ~12° difference in orientation. (b). Overlay of the BC domain of ScACC holoenzyme (in red) with the BC domain alone (in gray) in complex with soraphen A (green, labeled Sor)16. The region of large conformational differences is highlighted in light blue. The view is the same as panel a. (c). Detailed view of the conformational changes in the dimer interface. Blue arrows indicate some of the changes from the BC domain alone (gray) to the BC domain in the holoenzyme (red). (d). Conformational changes near the biotin binding site, especially the β19–β20 loop. This is coupled to changes in the β2 to αF segment. A possible hydrogen bond between the amide linkage of biotin and the β19–β20 loop is indicated with the dashed lines (red). (e). A model for how conformational transitions in the dimer interface affect catalysis and dimerization of the eukaryotic BC domain, updated from an earlier model25. Biotin is shown as the fused black pentagons, while soraphen A and phosphorylated serine are indicated by Sor and P, respectively. Bacterial BC subunit does not undergo the conformational transition, and its monomers can be catalytically active25.

The two distinct conformations of this domain explain why it is catalytically inactive on its own15 and also define the molecular mechanism for the inhibition of eukaryotic ACC by the natural product soraphen A16 and by phosphorylation of a Ser residue just prior to the BC domain core in mammalian ACC (Ser80 in human ACC1 and Ser222 in ACC2)23 (Extended Data Fig. 1). As a part of the conformational change, residues in the β19–β20 loop move by up to 10 Å (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Video 2). This loop in the structure of BC domain alone is likely to interfere with the binding of BCCP-biotin (Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 7), based on the binding mode of biotin to E. coli BC26. Consequently, BC domain alone is catalytically inactive because it assumes a conformation that cannot bind the BCCP-biotin substrate.

Soraphen A recognizes the conformation of isolated BC domain16, and this binding site does not exist in the BC domain dimer in the holoenzyme due to the structural changes (Fig. 3c). For example, strands β19 and β20 move into the binding site, and especially the side chain of Trp487 (β19) is in direct clash with soraphen A (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 7). Therefore, soraphen A inhibits the enzyme allosterically by stabilizing a catalytically inactive conformation of the BC domain. In the context of the holoenzyme, soraphen A binding will disrupt the formation of BC domain dimer (Fig. 1d), as the other protomer has clash with the compound as well (Extended Data Fig. 7). This could also be detrimental for catalysis as the BC domains may not be positioned correctly to accept the BCCP-biotin for carboxylation.

Upon phosphorylation, the peptide segment containing pSer222 of human ACC2 is located in the same binding site as soraphen A23, and the Trp487 side chain in the holoenzyme structure also clashes with this segment (Extended Data Fig. 7). Therefore, phosphorylation of this Ser residue inhibits the enzyme through the same mechanism as that of soraphen A. These structural observations greatly extend a model for the inhibitory mechanism proposed earlier25 (Fig. 3e). ScACC does not have an equivalent phosphorylation site in this region of the sequence.

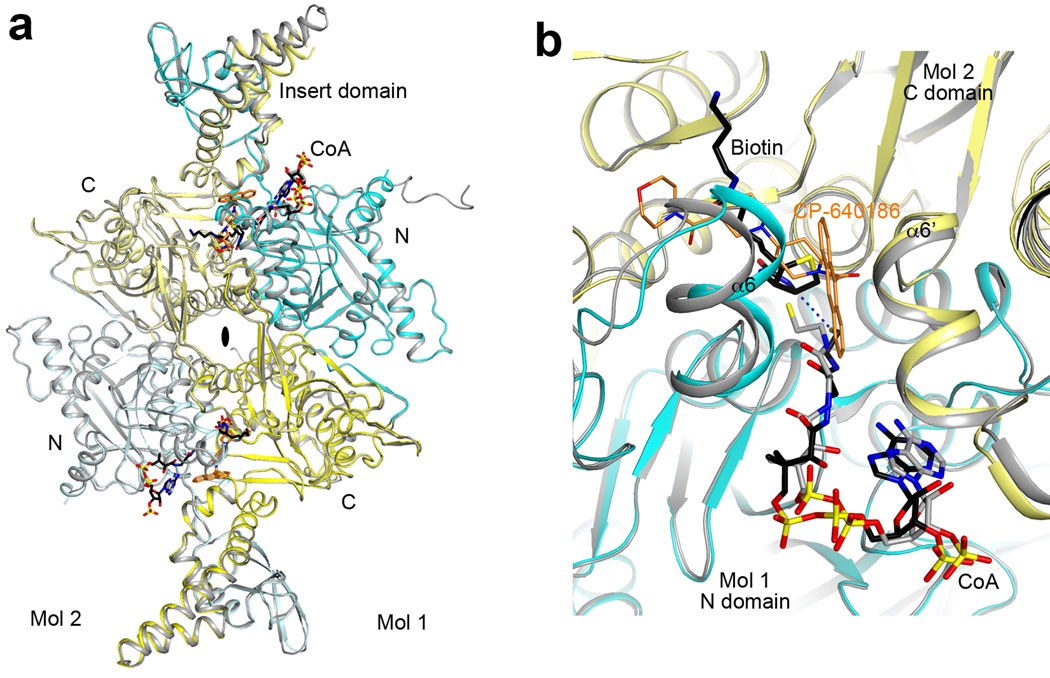

In comparison, the structure of the CT domain dimer in the holoenzyme is essentially the same as that of the domain alone17, with rms distance of 0.61 Å among their equivalent Cα atoms (Extended Data Fig. 8). The binding of both BCCP-biotin and CoA (Extended Data Fig. 4) in one of the CT active sites provides direct insights into the catalysis by this enzyme. The thiol group of CoA is 4.3 Å away from the N1′ atom of biotin (Extended Data Fig. 8). Therefore, the two substrates are likely in the correct positions for catalysis. The position of biotin clashes with that of the compound CP-640186 (Extended Data Fig. 8), a nanomolar inhibitor of mammalian ACCs27, confirming that it functions by blocking biotin binding to the CT active site28.

Prior to the structure determination of the holoenzyme, we obtained the crystal structures for residues 797–1033 (domains AC1–2), 1036–1503 (AC3–5), and 569–1494 (BT, BCCP and the entire central region) (Extended Data Table 1). Comparisons of the structures of these domains alone with that of the holoenzyme reveal substantial variability in the relative positioning of the domains. Domains AC3–4 in the structure of AC3–5 alone can be readily superposed with those in the holoenzyme, but then the orientation of domain AC5 differ by 40° (Extended Data Fig. 9). Even more variability is observed in the structure of BT-BCCP-AC1–5 alone, illustrated by the differences in the positioning of AC1–2 relative to the BT domain and AC3–5 (Extended Data Fig. 9). Interestingly, between the two unique copies of the BT-BCCP-AC1–5 molecule in the crystal, one has a conformation of AC3–5 that is very similar to that in the holoenzyme (Extended Data Fig. 9), while the other is similar to that in AC3–5 alone, suggesting that domains AC3–5 may assume two (or more) distinct conformations.

Another discovery from the structure is that the central region has minimal contributions to the formation of the dimer. Besides the ~300 Å2 surface area burial for AC1 and AC2 (Fig. 2c), the central region has no contacts with the other protomer (Fig. 1b). On the other hand, the structure suggests that the central region is important for maintaining the BC and CT dimers in the correct relative positions for catalysis. The CT domain dimer is sandwiched by AC5 on both sides (Fig. 1e). The BT and AC2 domains of the two protomers form a platform, keeping the BC domain dimer in place and possibly also helping with BC domain dimerization (Fig. 1b). The conformational variability observed for the domains in the central region (Extended Data Fig. 9) might play a role in regulating the activity of the holoenzyme.

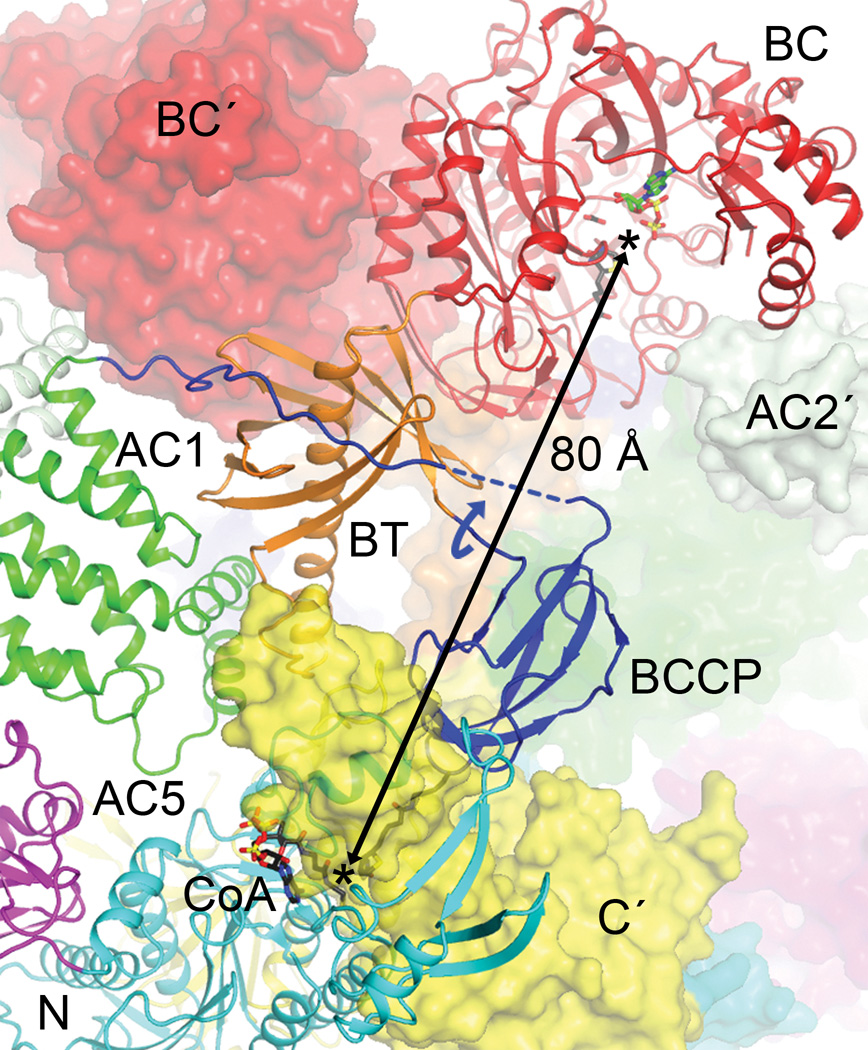

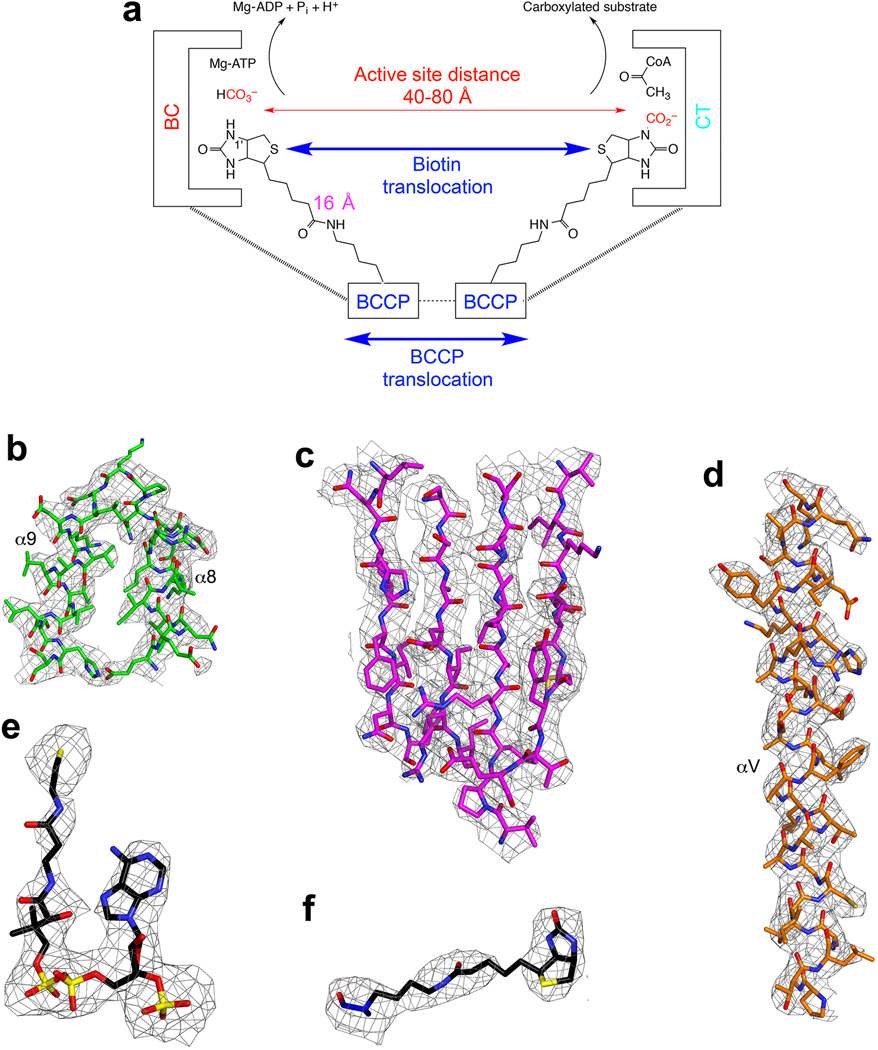

The structural analysis indicates that BCCP-biotin becomes carboxylated in the BC active site of its own protomer, and then translocates to the CT active site at the dimer interface, where it contacts the C domain of the other protomer (Fig. 4). The distance between the BC and CT active sites is ~80 Å, indicating that the entire BCCP domain must translocate during catalysis (swinging-domain model, Extended Data Fig. 4), as has been observed in the other holoenzymes1,9–14. In fact, the linker from BT to BCCP (residues 697–700) is about 45 Å from the N1′ atom of biotin, and therefore a rotation of this linker by ~180° could bring the biotin into the BC active site from the CT active site (Fig. 4). The linker from BCCP to AC1 (residues 770–795) is much longer and can accommodate such a rotation, and part of this linker is disordered in the current structure.

Figure 4.

Translocation of BCCP and biotin during ACC catalysis. The BC and CT active sites (black asterisks) of ScACC are separated by ~80 Å (arrow). A rotation of ~180° around the BT-BCCP linker (curved arrow in blue) could place the biotin into the BC active site. The prime in the labels indicates the second protomer. The binding modes of ADP (green) and biotin (black) to E. coli BC subunit are shown as stick models26.

We introduced mutations in the interfaces in the holoenzyme to assess the structural information. The mutants that could be purified migrated at the same position on a gel filtration column and had nearly the same thermal melting curves as the wild-type enzyme (data not shown). Deletion of the α-helical hairpin (α8–α9, residues 940–972) in domain AC1 (Extended Data Fig. 2) or the β4A–β4B loop in the C domain of CT (residues 1902–1916, Extended Data Fig. 3) abolished the catalytic activity (Table 1), demonstrating their importance in anchoring the hook of the BT domain (Fig. 2b). On the other hand, mutating Gln608 in the hook, which interacts with the main chain of the β4A–β4B loop (Fig. 2b), had little effect on catalysis. Similarly, the R656E mutation at the edge of the BT-BC interface (Fig. 2a) had little effect, suggesting that these single-site mutations are not sufficient to disrupt the holoenzyme or that these regions of contact do not contribute significantly to the interactions.

Table 1.

Effects of mutations in the ScACC holoenzyme interfaces on the catalysis.

| Enzyme | Km (mM)* | kcat (s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type ScACC | 0.053±0.011 | 8.5±0.4 |

| Δ940–972 (α8–α9 hairpin of AC1) | No activity detected | |

| Δ1902–1916 (β4A–β4B loop of CT) | No activity detected | |

| Δ836–918 (AC2) | No expression | |

| K73E | Very low activity | |

| R76E | No activity detected | |

| Y83A | 0.074±0.020 | 1.6±0.1 |

| W487A | Very low activity | |

| Q608R | 0.11±0.02 | 16±1.0 |

| R656E | 0.15±0.07 | 5.0±0.6 |

The errors were obtained from fitting data to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

We introduced the K73E, R76E and W487A mutation in the BC domain dimer interface (Extended Data Fig. 7), and all three essentially abolished the catalytic activity (Table 1). The mutations likely disrupted the BC domain dimer, and the domain changed to the other conformation that is incompatible with catalysis. The K73E and R76E mutants are equivalent to the R16E and R19E mutants of E. coli BC subunit that we characterized earlier25,29. Those mutations greatly destabilized the dimer, but had only a small effect (about 3-fold) on the catalytic activity of the BC subunit alone, likely because E. coli BC monomer does not undergo the conformational transition as observed here for eukaryotic BC (Fig. 3e). However, the R19E mutation had a much larger effect in vivo, likely in the context of the E. coli ACC holoenzyme30.

Overall, our studies have produced the first structural information on the 500 kD yeast ACC holoenzyme dimer. This structure is likely to have relevance for other eukaryotic ACCs, especially the human ACC holoenzymes, as they share 45% sequence identity with yeast ACC. The structures of the BC and CT domains of human and yeast ACCs are highly similar, consistent with their strong sequence conservation (Extended Data Figs. 1, 3). Although the sequence conservation for the central region is weaker, the secondary structure elements in yeast ACC are predicted to be present in human ACC as well, and residues in these secondary structure elements are more conserved than those in the loops (Extended Data Fig. 2). Therefore, the overall structure of human ACC holoenzyme is likely to be similar to that of yeast ACC.

Online Methods

Protein expression and purification

The N-terminal segment of the central region of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ACC (ScACC, gene ACC1, residues 797–1033, AC1–2 domains) was expressed at 20 °C in E. coli BL21(DE3) Star cells for native protein or B384(DE3) cells for selenomethionyl protein, in the presence of a chaperone plasmid pG-KJE8 (TaKaRa). The recombinant protein carried a C-terminal His-tag and was purified by Ni-NTA (Qiagen) and gel filtration chromatography (Sephacryl S-300, GE Healthcare) in buffer A (20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT).

The C-terminal segment of the central region of ScACC (residues 1036–1503, AC3–5 domains) was expressed in E.coli B834(DE3) cells at 25 °C for selenomethionyl protein and purified following the same protocol. The gel filtration buffer contained 10 mM rather than 2 mM DTT.

The segment containing the BT-BCCP-AC domains of ScACC (residues 569–1494) was expressed in BL21(DE3) Rosetta cells at 24 °C. The recombinant protein, with a C-terminal His-tag, was purified by Ni-NTA and gel filtration chromatography in buffer A.

Full-length ScACC (residues 1–2233) was constructed into pET28a (Novagen) by sewing together two PCR fragments with a 900-nt overlap. For structure determination, the segment containing residues 22–2233, with a C-terminal His-tag, was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) Star cells at 25 °C. Protein expression for all the different ScACC segments was driven by the trp promoter and was induced with 3-indoleacrylic acid. However, the endogenous E. coli biotin-protein ligase (BPL, also known as BirA) was not able to biotinylate the ScACC. The ScBPL gene was amplified from the genome and inserted into the pCDFDuet-1 vector (Novagen) multiple cloning site 2 without any affinity tag. Co-expression of ScBPL and the inclusion of 20 mg/l biotin in the media allowed complete biotinylation of ScACC, confirmed by an avidin shift assay. The protein was purified by Ni-NTA and gel filtration chromatography in buffer A. Typically 0.5 mg of biotinylated ScACC (or 3 mg of unbiotinylated ScACC) could be purified from 12 liters of culture.

Protein crystallization

Crystals were obtained at 20 °C using the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method. Native and selenomethionyl crystals of the AC1–2 domains were obtained using a precipitant solution of 90 mM Bis-tris propane and 60 mM citric acid (pH 6.4), and 20% (w/v) PEG3350. The protein concentration was 12 mg/ml, and the crystals took 3 weeks to reach full size.

Selenomethionine-substituted crystals of the AC3–5 domains were obtained after 2 days. The protein concentration was 3.6 mg/ml, and the precipitant solution contained 80 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 4 % (v/v) MPD, 8 mM sodium citrate, 4% (v/v) glycerol, and 40mM NDSB-201.

Native crystals of the BT-BCCP-AC domains were obtained after 4 days. The protein concentration was 15 mg/ml, and the precipitant solution contained 80 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 9.6% (w/v) PEG6000, 1.6% (v/v) MPD, 60 mM sodium citrate, and 80 mM NaI.

Full-length ACC protein was incubated with 3.3 mM acetyl-CoA and 3.3 mM Mg-ADP for 30 min on ice prior to crystallization. Crystals were obtained after 2 weeks. The protein concentration was 5 mg/ml, and the precipitant solution contained 14% (w/v) PEG3350, 4% (v/v) tert-butanol, and 0.2 M sodium citrate.

Glycerol was used as the cryo-protectant and all crystals were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for data collection at 100K.

Data collection and structure determination

X-ray diffraction data of AC1–2 domains were collected on an ADSC Q315 CCD at the X29A beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS). The diffraction images were processed with the HKL program31. The crystal belonged to space group P65 with cell parameters of a = b = 117.6 Å, and c = 73.8 Å. There is a domain-swapped dimer of the protein in the asymmetric unit. A selenomethionyl single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) data set was collected to 3.0 Å resolution (wavelength 0.979 Å) and a native data set to 2.5 Å resolution (wavelength 1.075 Å). Five Se atoms were located with program Solve32 and used for phasing with program Phenix33. The phase information was then extended to 2.5 Å with solvent flattening, histogram matching and two-fold non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging using the program DM in CCP434. The atomic model was built into the electron density map manually with the program Coot35. Structure refinement was performed with CNS36 and Refmac537.

A selenomethionyl SAD data set to 3.2 Å resolution of AC3–5 domains was collected at the X29A beamline (wavelength 0.979 Å). The crystal belonged to space group P21, with cell parameters of a = 56.8 Å, b = 93.3 Å, c = 111.1 Å, and β = 100.6 °. There are two molecules in the asymmetric unit. Five Se atoms in each molecule were located and employed for phasing with program Phenix. An atomic model was manually built into the electron density map with program Coot, and the structure was refined with Refmac5.

A native diffraction data set to 3.0 Å resolution of BT-BCCP-AC domains was collected at the X29A beamline (wavelength 1.075 Å). The crystal belonged to space group P21, with cell parameters of a = 93.3 Å, b = 149.7Å, c = 95.4Å, and β = 118.4 °. There is a dimer of the protein in the asymmetric unit. The structures of AC1–2 and AC3–5 domains were used as the search models to solve the structure by molecular replacement with the program Phaser38. The BT and BCCP domains were manually built into the electron density map.

A native diffraction data set to 3.1 Å resolution of residues 22–2233 of un-biotinylated ScACC was collected on a Pilatus 6M detector at the X25 beamline of NSLS (wavelength 1.100 Å). There is a dimer of ScACC in the asymmetric unit. The structure was solved by molecular replacement with the program Phaser. The structures of AC1–2, AC3–5, and BT domains reported here and previously published structures of yeast BC16 and CT domains17 were used as the search models. However, no electron density for the BCCP domain was observed based on the crystallographic analysis.

A native diffraction data set to 3.2 Å resolution of biotinylated ScACC was collected at the X25 beamline. The crystal belonged to space group P43212, with cell parameters of a = b = 159.8 Å, and c = 614.1 Å, isomorphous to that of the un-biotinylated ScACC. The final atomic model was built with Coot and refined with Refmac5. NCS restraints were used during the refinement. Crystals of full-length ScACC (residues 1–2233) did not diffract beyond 8 Å resolution even after extensive efforts. The geometry of the final model was validated with MolProbity39.

Mutagenesis and kinetic assays

Site-specific and deletion mutations were introduced with the QuikChange kit (Agilent) and sequenced for confirmation. In deletion mutants, residues 940–972 of the α-helical hairpin (α8–α9) in domain AC1 and residues 836–918 in domain AC2 were replaced by a (GS)3 linker, respectively, while residues 1902–1916 of the β4A–β4B loop in the C domain of CT were replaced by a (GS)2 linker.

The catalytic activity of ACC was determined using a coupled enzyme assay, converting the hydrolysis of ATP to the disappearance of NADH40. The reaction mixture contained 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 8 mM MgCl2, 40 mM KHCO3, 200 mM KCl, 0.2 mM NADH, 0.5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.5 mM ATP, 6 units of lactate dehydrogenase (Sigma), 4 units of pyruvate kinase, 100 nM ACC and various concentrations of acetyl-CoA. The absorbance at 340 nm was monitored for 60 sec.

Extended Data

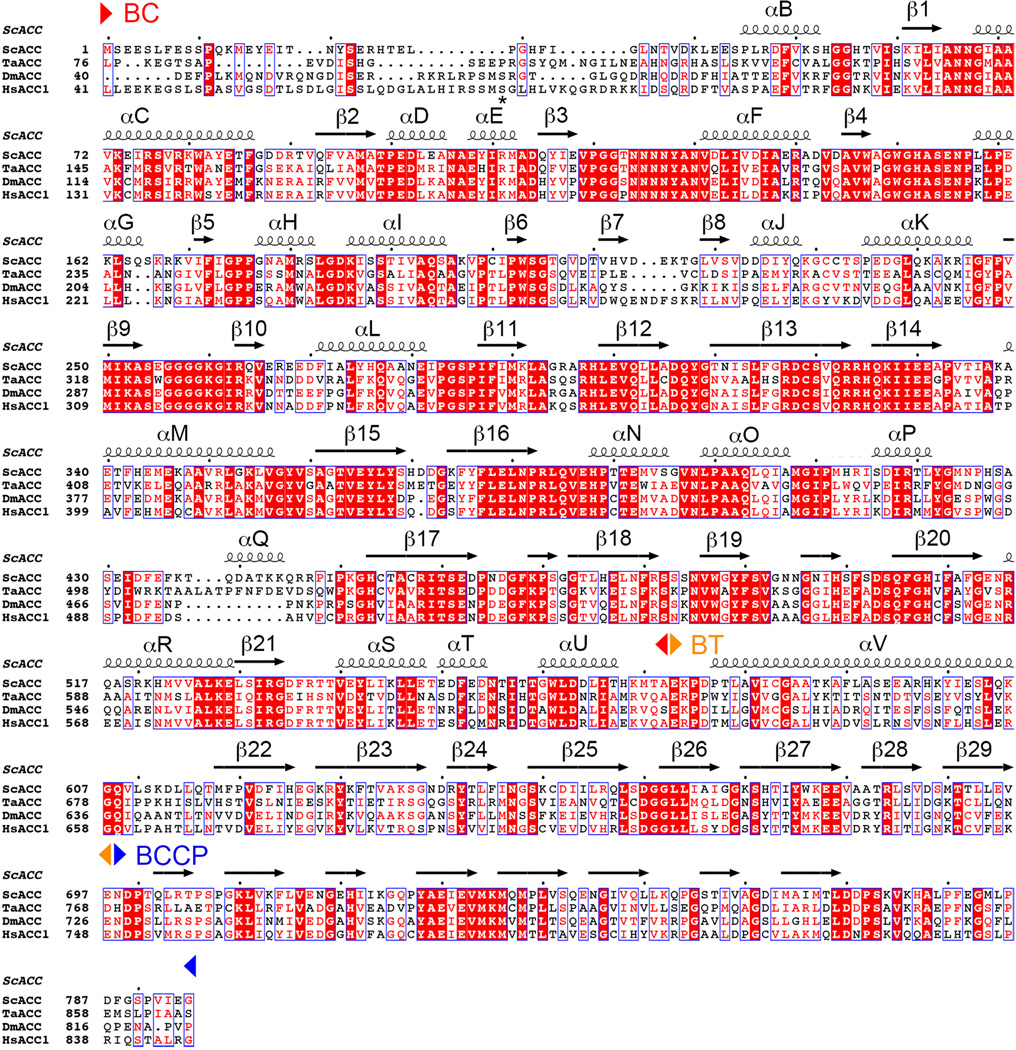

Extended Data Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment of the N-terminal region of eukaryotic, single-chain ACCs. The region includes BC, BT and BCCP domains (indicated). The secondary structure elements in the ScACC holoenzyme structure are shown. The site of phosphorylation in HsACC1 (Ser80) is indicated with a star. This site does not exist in ScACC. ScACC: Saccharomyces cerevisiae ACC, TaACC: Triticum aestivum (wheat) ACC, DmACC: Drosophila melanogaster ACC; HsACC1: Homo sapiens ACC1. Modified from an output from ESPript.41

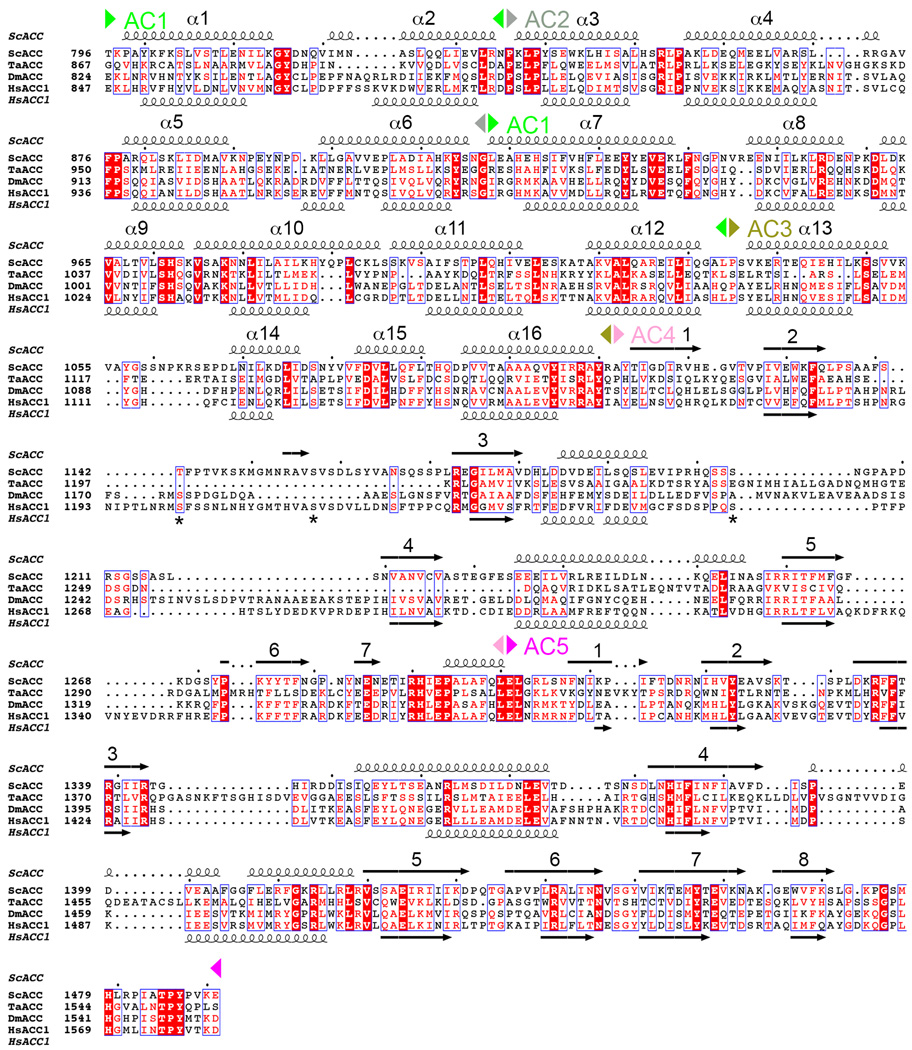

Extended Data Fig. 2.

Sequence alignment of the central region of eukaryotic, single-chain ACCs. The AC1–5 domains are indicated. Predicted secondary structure elements in HsACC1 are also shown, and they generally match those in the structure of ScACC. The helices in AC1–3 are numbered consecutively. Three sites of phosphorylation in HsACC1 are indicated with stars.

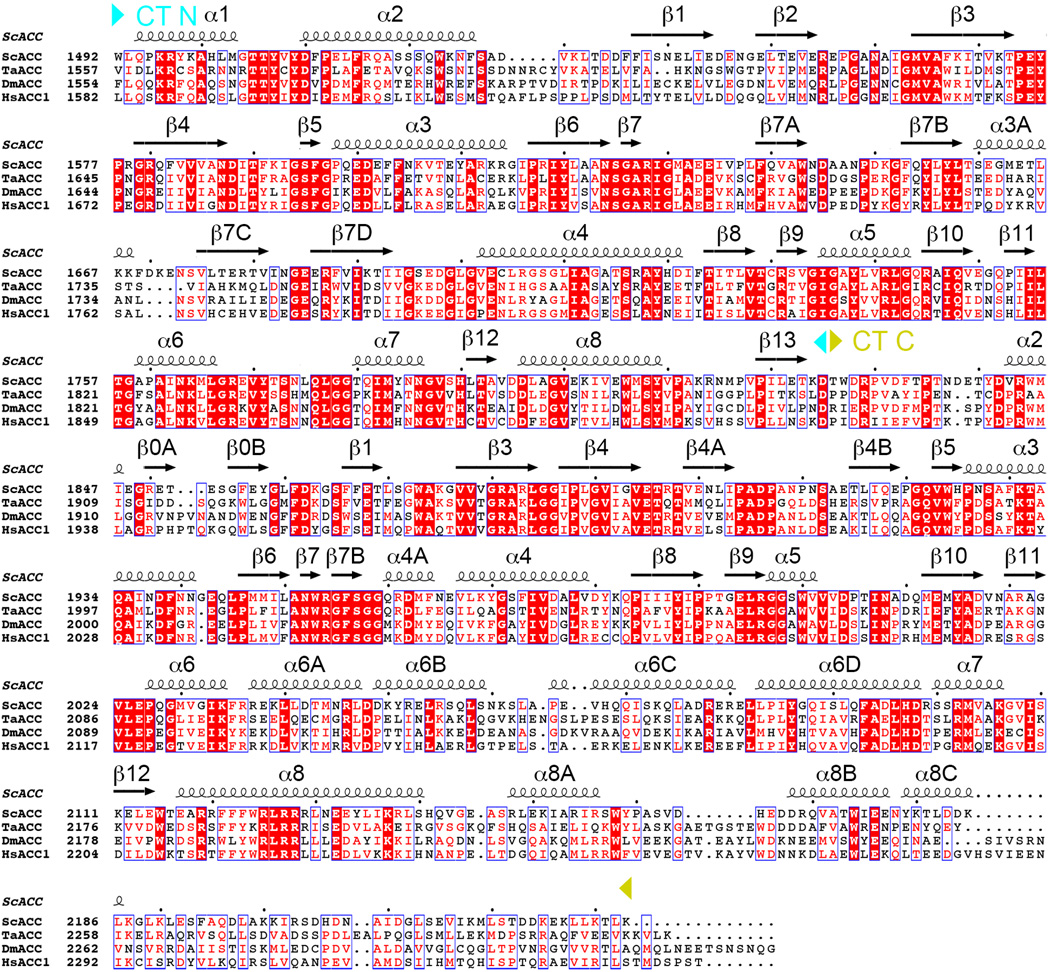

Extended Data Fig. 3.

Sequence alignment of the C-terminal region of eukaryotic, single-chain ACCs. The region includes N and C domains of CT (indicated).

Extended Data Fig. 4.

Electron density for various regions of the ScACC holoenzyme structure. (a). Schematic of the two-step reaction in the catalysis by biotin-dependent carboxylases. Biotin is carboxylated in the BC active site, and then translocates to the CT active site where the substrate is carboxylated. The longest distance from the N1′ atom of biotin to the Cα atom of the Lys residue covalently attached to biotin is ~16 Å, giving a reach of ~30 Å for biotin (swinging-arm model). The actual distance between the BC and CT active sites are larger than 30 Å, suggesting that BCCP needs to translocate in addition to the biotin (swinging-domain model).

(b). 2Fo–Fc electron density for the helical hairpin insert (α8–α9) of domain AC1 at 3.2 Å resolution, contoured at 1σ. (c). 2Fo–Fc electron density for the β-sheet of domain AC5. (d). 2Fo–Fc electron density for the central helix (αV) of the BT domain. (e). Omit Fo–Fc electron density for CoA at 3.2 Å resolution, contoured at 2.5σ. (f). Omit Fo–Fc electron density for biotin at 3.2 Å resolution.

Extended Data Fig. 5.

Overall structure of the ScACC holoenzyme. (a). A large channel in the center of the ScACC holoenzyme dimer. The view is related to that of Fig. 1b by an ~30° rotation around the vertical axis. (b). Overlay of the structures of the two protomers of ScACC holoenzyme dimer. One protomer is shown in color and other in gray. The overlay is based on the CT domain. Differences in the orientations of the other domains are indicated, as well as the rms distance for their equivalent Cα atoms. The arrow points to conformational differences in the insert domain of CT, linked to differences in the BCCP binding mode. (c). Overlay of the BT domain of ScACC (in orange) and the BT domain of PCC (in gray). The ‘hook’, connecting the end of the helix (αV) to the first strand of the β-barrel (β22), is labeled. The last three strands of the β-barrel (β27–β29) are splayed further away from the central helix in ScACC compared to PCC. (d). Interactions between the hook of the BT domain and the β4A–β4B loop from the C domain of CT, an inserted segment that projects away from the rest of the domain. (e). The BCCP-AC1 linker has hydrophobic interactions with the top of one side of the BT domain β-barrel. The disordered segment of the linker is indicated with the blue line.

Extended Data Fig. 6.

Domains AC4 and AC5 share a common backbone fold. (a). Structure of AC4 domain of ScACC. (b). Topological drawing of AC4 domain. (c). Structure of AC5 domain. (d). Topological drawing of AC5 domain. (e). Overlay of the structures of AC5 domain (magenta) and formamidase (gray). Formamidase has a four-layered αββα structure, and AC5 matches only half of the structure.

Extended Data Fig. 7.

Structure of the BC domain dimer of ScACC. (a). Interactions in the BC dimer interface. The BC domain of protomer 1 is in red, and that of protomer 2 in pink. (b). Residues in the BC dimer interface (in red) of ScACC and E. coli BC (EcBC) are weakly conserved among the biotin-dependent carboxylases. MapLCC: long-chain acyl-CoA carboxylase of Mycobacterium avium subspecies tuberculosis. (c). A BC domain dimer is constructed by superposing the structure of BC domain alone (in complex with soraphen A, green) onto that of the BC dimer. Regions of steric clashes between the two monomers are highlighted in light blue. (d). Closeup view of the binding site of biotin. The β19–β20 loop in the structure of BC domain alone (gray) clashes with biotin (red arrow), and cannot interact with the amide group of the biotin linkage (red dashed lines). (e). Closeup view of the soraphen A (green) binding site. The movement of strands β19 and β20 from the structure of BC domain alone in complex with soraphen A (gray) is indicated with the arrows. Trp487 side chain in the holoenzyme structure clashes with soraphen A as well as the phosphorylated peptide segment containing pSer222 (light blue).

Extended Data Fig. 8.

Structure of the CT domain dimer of ScACC. (a). Overlay of the CT domain dimer in the ScACC holoenzyme (cyan and yellow for N and C domains of protomer 1, light cyan and light yellow for protomer 2) in complex with CoA (black) with the CT domain alone in complex with CoA (gray). Biotin is shown in black and BCCP is omitted for clarity. The bound position of the CP-640186 inhibitor (gold) is shown for reference. A conformational change for the insert domain at the top is due to the binding of BCCP in the holoenzyme, while the insert domain at the bottom shows essentially no change because the BCCP-biotin is not bound as deeply into this active site. (b). Overlay of the CT active site (cyan and yellow) of ScACC holoenzyme with that of CT alone in complex with CoA (gray). The CP-640186 inhibitor (gold) clashes with the bound position of biotin (black). The thiol group of CoA in the holoenzyme complex is 4.3 Å from the N1 atom of biotin (dashed line in blue). The thiol group of CoA in the CT domain alone complex is in a different position, likely due to the absence of biotin in the active site.

Extended Data Fig. 9.

Comparisons of the structures of ACC central region alone with that in the holoenzyme. (a). Overlay of AC1–2 in the holoenzyme (color) with AC1–2 alone (yellow and gray). The first helix is swapped between two monomers in the structure of AC1–2 alone, and the two-fold axis of that dimer is indicated with the black line. (b). Overlay of AC3–5 in the holoenzyme (color) with AC3–5 alone (gray), based on AC3–4. A large difference is seen for the orientation of AC5. (c). Overlay of BT-BCCP-AC1–5 in the holoenzyme (color) with these domains alone (gray), based on AC1–2. Large differences are seen for BT, BCCP and AC3–5. (d). Overlay of BT-BCCP-AC1–5 in the holoenzyme (color) with these domains alone (gray), based on AC3–4. Large differences are seen for BT, BCCP and AC1–2, although AC5 has essentially the same position.

Extended Data Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| ScACC holoenzyme |

ScACC (unbiotinylated) |

AC1–2 | AC3–5 | BT-BCCP-AC1–5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Space group | P43212 | P43212 | P65 | P21 | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 159.8, 159.8, 614.1 | 159.9, 159.9, 615.5 | 117.6, 117.6, 73.8 | 56.8, 93.3, 111.1 | 93.3, 149.7, 95.4 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 100.6, 90 | 90, 118.4, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–3.2 (3.3–3.2)* | 50–3.1 (3.2–3.1) | 50–2.5 (2.6–2.5) | 50–3.2 (3.3–3.2) | 50–3.0 (3.1–3.0) |

| Rmerge | 14.8 (90.1) | 10.9 (88.1) | 7.1 (41.6) | 7.5 (40.5) | 8.8 (44.9) |

| CC1/2 | (0.448) | (0.452) | (0.965) | (0.848) | |

| I/σI | 7.0 (1.0) | 8.2 (1.1) | 18.6 (2.6) | 21.9 (5.1) | 13.7 (2.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 98 (87) | 93 (90) | 100 (99) | 100 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Redundancy | 3.0 (2.7) | 2.3 (2.3) | 4.2 (3.6) | 7.6 (7.6) | 3.4 (3.4) |

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 50–3.2 | 50–3.1 | 50–2.5 | 50–3.2 | 50–3.0 |

| No. reflections | 122,246 | 129,166 | 19,205 | 18,134 | 42,803 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 21.9 / 26.6 | 21.7 / 28.1 | 21.4 / 26.9 | 23.8 / 28.6 | 23.0 / 28.9 |

| No. atoms | |||||

| Protein | 32,651 | 31,816 | 3,370 | 6,353 | 13,699 |

| Ligand/ion | 126 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Water | 0 | 0 | 45 | 0 | 0 |

| B-factors | |||||

| Protein | 96.8 | 93.2 | 79.2 | 87.9 | 74.9 |

| Ligand/ion | 106.2 | – | – | – | – |

| Water | – | – | 61.0 | – | – |

| R.m.s deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

One crystal was used for data collection.

Highest resolution shell is shown in parenthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Martin Bush, Chi-Yuan Chou, Yang Shen, Linda Yu and Hailong Zhang for carrying out initial studies in this project; R. Jackimowicz, B. Nolan, N. Whalen, A. Heroux and H. Robinson for access to the X29A and X25 beamlines at the NSLS; S. Banerjee, K. Perry, R. Rajashankar, J. Schuermann, N. Sukumar for access to NE-CAT 24-C and 24-E beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source; W. Rice and E. Eng at New York Structural Biology Center for assistance with electron microscopy. The in-house X-ray diffraction instrument was purchased with an NIH grant to LT (S10OD012018). This research was supported in part by a grant from the NIH (R01DK067238) to LT.

Footnotes

Author Contributions. JW carried out protein expression, purification, crystallization, data collection, structure determination and refinement, site-directed mutagenesis and enzymatic assays. LT initiated the project, supervised the entire research, and analyzed the results. JW and LT wrote the paper.

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 5CS0 for AC1–2, 5CS4 for AC3–5, 5CSA for BT-BCCP-AC1–5, 5CSK for unbiotinylated ACC, and 5CSL for ACC holoenzyme.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Tong L. Structure and function of biotin-dependent carboxylases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013;70:863–891. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1096-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waldrop GL, Holden HM, St. Maurice M. The enzymes of biotin dependent CO2 metabolism: what structures reveal about their reaction mechanisms. Prot. Sci. 2012;21:1597–1619. doi: 10.1002/pro.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cronan JE, Jr, Waldrop GL. Multi-subunit acetyl-CoA carboxylases. Prog. Lipid Res. 2002;41:407–435. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(02)00007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polyak SW, Abell AD, Wilce MCJ, Zhang L, Booker GW. Structure, function and selective inhibition of bacterial acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;93:983–992. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3796-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramson HN. The lipogenesis pathway as a cancer target. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:5615–5638. doi: 10.1021/jm2005805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wakil SJ, Abu-Elheiga LA. Fatty acid metabolism: target for metabolic syndrome. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:S138–S143. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800079-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneiter R, et al. A yeast acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase mutant links very-long-chain fatty acid synthesis to the structure and function of the nuclear membrane-pore complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:7161–7172. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.7161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoja U, Wellein C, Greiner E, Schweizer E. Pleiotropic phenotype of acetyl-CoA-carboxylase-defective yeast cells Viability of a BPL1-amber mutation depending on its readthrough by normal tRNA(Gln)(CAG) Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;254:520–526. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.St. Maurice M, et al. Domain architecture of pyruvate carboxylase, a biotin-dependent multifunctional enzyme. Science. 2007;317:1076–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.1144504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang S, Tong L. Crystal structures of human and Staphylococcus aureus pyruvate carboxylase and molecular insights into the carboxyltransfer reaction. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:295–302. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang CS, et al. Crystal structure of the a6b6 holoenzyme of propionyl-coenzyme A carboxylase. Nature. 2010;466:1001–1005. doi: 10.1038/nature09302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang CS, Ge P, Zhou ZH, Tong L. An unanticipated architecture of the 750-kDa a6b6 holoezyme of 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase. Nature. 2012;481:219–223. doi: 10.1038/nature10691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan C, Chou C-Y, Tong L, Xiang S. Crystal structure of urea carboxylase provides insights into the carboxyltransfer reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:9389–9398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.319475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tran TH, et al. Structure and function of a single-chain, multi-domain long-chain acyl-CoA carboxylase. Nature. 2015;518:120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature13912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weatherly SC, Volrath SL, Elich TD. Expression and characterization of recombinant fungal acetyl-CoA carboxylase and isolation of a soraphen-binding domain. Biochem. J. 2004;380:105–110. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen Y, Volrath SL, Weatherly SC, Elich TD, Tong L. A mechanism for the potent inhibition of eukaryotic acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase by soraphen A, a macrocyclic polyketide natural product. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:881–891. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Yang Z, Shen Y, Tong L. Crystal structure of the carboxyltransferase domain of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase. Science. 2003;299:2064–2067. doi: 10.1126/science.1081366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman-Smith A, Forbes BE, Wallace JC, Cronan JE., Jr Covalent modification of an exposed surface turn alters the global conformation of the biotin carrier domain of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26017–26022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.26017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solbiati J, Chapman-Smith A, Cronan JE., Jr Stabilization of the biotinoyl domain of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase by interactions between the attached biotin and the protruding "thumb" structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21604–21609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hung CL, et al. Crystal structure of Helicobacter pylori formamidase AmiF reveals a cysteine-glutamate-lysine catalytic triad. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:12220–12229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holm L, Kaariainen S, Rosenstrom P, Schenkel A. Searching protein structure databases with DaliLite v.3. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2780–2781. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raymer B, et al. Synthesis and characterization of a BODIPY-labeled derivative of soraphen A that binds to acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:2804–2807. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho YS, et al. Molecular mechanism for the regulation of human ACC2 through phosphorylation by AMPK. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;391:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waldrop GL, Rayment I, Holden HM. Three-dimensional structure of the biotin carboxylase subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Biochem. 1994;33:10249–10256. doi: 10.1021/bi00200a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen Y, Chou C-Y, Chang G-G, Tong L. Is dimerization required for the catalytic activity of bacterial biotin carboxylase? Mol. Cell. 2006;22:807–818. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou C-Y, Yu LPC, Tong L. Crystal structure of biotin carboxylase in complex with substrates and implications for its catalytic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:11690–11697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805783200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harwood HJ, Jr, et al. Isozyme-nonselective N-substituted bipiperidylcarboxamide acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitors reduce tissue malonyl-CoA concentrations, inhibit fatty acid synthesis, and increase fatty acid oxidation in cultured cells and in experimental animals. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:37099–37111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304481200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Tweel B, Li J, Tong L. Crystal structure of the carboxyltransferase domain of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase in complex with CP-640186. Structure. 2004;12:1683–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou C-Y, Tong L. Structural and biochemical studies on the regulation of biotin carboxylase by substrate inhibition and dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:24417–24425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.220517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith AC, Cronan JE. Dimerization of the bacterial biotin carboxylase subunit is required for acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase activity in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:72–78. doi: 10.1128/JB.06309-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References for Online Methods

- 31.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Method Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terwilliger TC. SOLVE and RESOLVE: Automated structure solution and density modification. Meth. Enzymol. 2003;374:22–37. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: building a new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2002;D58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CCP4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emsley P, Cowtan KD. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. 2004;D60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR System: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Cryst. 1998;D54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Cryst. 1997;D53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Cryst. 2010;D66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blanchard CZ, Lee YM, Frantom PA, Waldrop GL. Mutations at four active site residues of biotin carboxylase abolish substrate-induced synergism by biotin. Biochem. 1999;38:3393–3400. doi: 10.1021/bi982660a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Extended Data References

- 41.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.