Abstract

Secondary syphilis develops in approximately 25 % of patients infected with the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum. It typically develops several weeks to several months after the primary infection, which is recognized by a painless chancre. Secondary syphilis is characterized by systemic symptoms, such as malaise and fever as well as a maculopapular rash involving the trunk and extremities including the palms and soles. Condyloma lata, which are raised, fleshy lesions, tend to develop at the site of the primary chancre. Diagnosis is achieved primarily through screening and confirmational serologic testing. Histologic findings seen in condyloma lata are largely non-specific. Therefore, a high index of suspicion should be maintained and immunohistochemical stains specific for T. pallidum should be utilized.

Keywords: Secondary syphilis, Condyloma lata, Treponema pallidum, Immunohistochemical

History

A 29 year-old MSM (men who have sex with men) presented to his primary care provider for a solitary non-painful “blister” involving his palate. At this appointment the patient recounted a sexual encounter with a new partner 2 weeks prior to the development of this lesion. A review of his medical history was significant for numerous sexually transmitted infections. Treatments for previous infections were well documented and the patient stated all his symptoms had resolved. Physical exam at the time revealed a solitary, well-circumscribed, one centimeter ulcerated lesion on the hard palate and white patches on the dorsal tongue. No laboratory tests were performed and the patient was treated for oral candidiasis. The patient continued to be concerned about changes in his palate and 6 weeks later he was evaluated by an otorhinolaryngologist. At that time, he complained of a 1-month history of an enlarging mass involving the hard and soft palate and a rash on his buttocks. Physical exam now revealed a non-ulcerated verruciform, fleshy lesion with focal erythema involving the hard and soft palate (Fig. 1) and a papular rash involving his buttocks. Biopsies of the palatal lesion were performed and submitted to pathology. Concurrent serologic testing for rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was positive and the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) confirmatory test was reactive.

Fig. 1.

Clinical photograph shows the condyloma lata, multiple papillary nodules of the soft and hard palate

Diagnosis

Histologic examination of hematoxylin and eosin stained slides show a non-ulcerated papillomatous lesion. The epithelium shows marked hyperplasia and a diffuse acute inflammatory infiltrate. There is a perivascular and subepithelial inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and abundant plasma cells (Figs. 2, 3). Immunohistochemical stains for spirochetes is positive (Fig. 4). The histologic findings are consistent with condyloma lata and in conjunction with the clinical presentation and serologic tests are consistent with the diagnosis of secondary syphilis.

Fig. 2.

Low power view shows papillary epithelial hyperplasia and a dense inflammatory infiltrate (×40)

Fig. 3.

Moderate power image shows a dense plasma cell and lymphocytic infiltrate (×200)

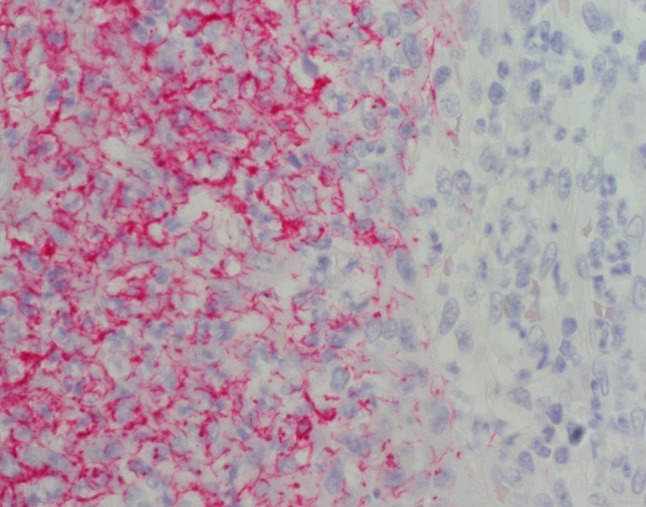

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical stain for Treponema pallidum shows numerous spirochetes (×400)

Discussion

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum. If untreated, the primary infection can progress to the more chronic secondary stage and latent stage infections. The latent stage is characterized by asymptomatic patients that lack physical signs of infection but have positive serology. A detailed discussion of the various stages is beyond the scope of this article, which will focus on secondary syphilis [1].

Secondary syphilis occurs in approximately 25 % of untreated patients, usually several weeks to a few months following the primary stage (painless clean-based chancre and lymphadenopathy). An accurate and thorough patient history is important, however the diagnosis of secondary syphilis requires a high index of clinical suspicion as the primary stage may go undiagnosed. Furthermore, the primary stage of syphilis may not develop in certain circumstances, such as in HIV positive patients [2, 3].

Patients typically manifest secondary syphilis with systemic symptoms including malaise, fatigue, fever, and headache as well as the hallmark rash, which is classically a maculopapular rash diffusely involving the trunk and extremities including the palms and soles. However, it is important to note that the rash may be localized, as was presumably the situation in the present case. Individual lesions are usually “copper” pigmented and may be pustular [4].

Mucosal involvement of the oral cavity, genital tract, or both, is common in the form of condyloma lata, which are raised, fleshy, white to gray lesions. Condyloma lata often develop within the vicinity of the primary chancre. Other manifestations of secondary syphilis to beware of include lymphadenopathy, alopecia, gastrointestinal symptoms secondary to ulcerations as well as renal and neurologic complications [2, 4].

Serologic testing remains the mainstay for diagnosis of syphilis as T. pallidum cannot be cultured. The traditional algorithm uses a nontreponemal serologic test for screening followed by a specific treponemal antigen serologic test for confirmation if the screening test is positive [3].

Nonspecific serologic tests rely on a serum antibody reaction to a non-treponemal cardiolipin-cholesterol-lecithin antigen. Available tests include Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and RPR. They are reported as a titer reflecting both IgM and IgG antibodies and can be used following treatment to demonstrate treatment response. False negative results may be seen in immunocompromised patients. False positive results have been reported in patients with various other infections, including non-treponemal spirochete infections and tuberculosis. False positive results have also been reported in intravenous drug users and pregnant women, and several other scenarios [2, 3].

Several treponemal serologic tests are available for confirmation, including the FTA-ABS (previously mentioned and used in the present case) as well as T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) and enzyme immunoassay (EIA). These tests identify antibodies directed to treponemal-specific antigens. Automation of these antigen specific tests, in particular the treponemal EIA, has resulted in some institutions switching from the traditional algorithm to using the specific treponemal antigen tests up front for screening. This reverse sequence testing approach may be more cost effective for institutions with a high volume of testing and it may be more valuable in previously treated patients where a repeat infection is suspected. For a complete review of screening recommendations please visit the Center for Disease Control and Prevention website [2, 3].

Direct diagnosis of syphilis can be accomplished by detecting organisms using dark field microscopy or direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) techniques. There are also investigational methods available including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and rapid point of care serologic tests, which will not be discussed in detail [2].

Histologic findings in both chancres and condyloma lata are largely non-specific and represent the progression of the body’s reaction to the infection. The obvious and largest distinction between chancres and condyloma lata are ulceration and papillomatosis, respectively. Both lesions classically show an acutely inflamed epithelium with numerous neutrophils as well as an underlying mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate rich with plasma cells. The hyperplastic epithelium seen in condyloma lata may be mistaken for condyloma acuminatum and other papillomatous lesions. Immunohistochemical stains specific for T. pallidum are available and should be utilized to assist the pathologist. Warthin Starry special stains for spirochetes are available as well, however these stains maybe inconsistent and more importantly they are non-specific as the normal oral flora includes numerous non-pathologic spirochetes. Of note, these non-pathologic spirochetes reside on the surface of the mucosa and are not seen invading into the mucosa. Since the histologic findings of primary and secondary syphilis are non-specific, a high index of suspicion is required by the pathologist and communication with the treating clinician is recommended as is the utilization of T. pallidum specific immunohistochemical stains.

In conclusion, syphilis is an infection caused by the bacterium T. pallidum and depending on the stage at presentation, has a spectrum of symptoms and signs. While a resurgence of syphilis has been suggested by some, it may be argued that it never went away, especially in high risk groups. The CDC reports an epidemiologic shift with an increase in the number of cases seen among young MSM. Awareness of at-risk populations will help to ensure proper tests are performed. As demonstrated in the present case, the diagnosis is usually made through serologic tests, however it must be emphasized that suspicion needs to be maintained by both clinicians and pathologists as the clinical and histologic findings may be subtle and mistaken for other more common diagnoses [3].

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author and are not to be construed as official or representing the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Koneman EW. Color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hicks CB and Sparling PF. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and treatment of early syphilis. 2013. Retrieved from http://www.uptodate.com.

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2014, January 7). Syphilis—CDC fact sheet. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov.

- 4.Singh AE, Romanowski B. Review with emphasis on clinical epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:187–209. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]