Abstract

PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome refers to a spectrum of disorders caused by mutations in the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) gene. Cowden syndrome, the principal PTEN-related disorder is characterized by multiple neoplasms and hamartomas, mucosal papillomatosis, and skin lesions, trichilemmomas. Trichilemmomas and mucocutaneous papillomatous papules are one of the first signs of the disease. Early recognition of these skin lesions may help on diagnosing an underlying malignancy and early cancer screening.

Keywords: PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS), Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) gene, Cowden syndrome (CS), Multiple neoplasms, Hamartomas, Mucosal papillomatosis, Trichilemmomas, Thyroid adenomatous nodules, Thyroid carcinoma, Adult Lhermitte–Duclos disease

Introduction

Multiple syndromes are now known to be associated with characteristic skin neoplasms. Features of these conditions that may assist in a diagnosis, prior to cancer development can be subtle and difficult to recognize [1]. The recognition of these skin lesions may facilitate the diagnosis of malignancies [2].

PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) is the molecular diagnostic term describing patients with diverse syndromes, comprising a spectrum of lesions that affect skin, mucous membranes, breast, thyroid gland, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract. It is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by a germline mutation in PTEN (phosphatase andtensin homolog, deleted on chromosome 10) (or MMAC1) localized to chromosome 10q22-23; it encodes a dual-specificity phosphatase which functions as a tumor suppressor [3]. While most cases are inherited in a family for generations, following an autosomal dominant pattern, 10 % to about 45 % of cases are due to a new (de novo) mutation.

Diagnostic criteria for Cowden syndrome (CS), the primary PTEN-related disorder, were first documented in 1996 before the identification of the PTEN gene [4]. Cowden syndrome is part of the PHTS, along with Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome (BRRS), Proteus syndrome (PS), and Proteus-like syndrome [5]. Cowden syndrome is a genodermatosis characterized by multiple hamartomas, neoplasms of ectodermal, mesodermal and endodermal origin. A diagnosis of CS is important because it confers a significant risk for cancer. Once a diagnosis of CS is made, there are screening and genetic counseling guidelines outlined by the NCCN [6]. Approximately 85 % of patients with CS harbor intragenic mutations of PTEN or mu-tations in the promoter region.

BRRS is a congenital disorder characterized by macrocephaly, intestinal hamartomatous polyposis, multiple thyroid nodules and tumors, lipomas, and pigmented macules of the glans penis [7].

PS is a complex, highly variable disorder involving congenital malformations and hamartomatous overgrowth of multiple tissues, as well as connective tissue nevi, epidermal nevi, and hyperostoses [8].

Proteus-like syndrome is undefined but refers to individuals with significant clinical features of PS who do not meet the diagnostic criteria for PS.

Discussion

CS is the most common syndrome of the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome diseases. CS is characterized by the development of multiple hamartomas and with a high risk for benign and malignant tumors of the thyroid, breast, and endometrium. Affected individuals usually have macrocephaly, trichilemmomas, and papillomatous papules, and present by the late 20 s.

Clinical criteria for CS based on guidelines put forth by the International Cowden Consortium [3] have been delineated by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). The NCCN has established testing criteria to indicate when PTEN testing is indicated, based on the clinical features present in a patient [6] and include pathognomonic, major, and minor criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical criteria for CS include pathognomonic, major, and minor criteria

| Pathognomonic lesions: operational diagnosis | Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Any single pathognomonic criteria: trichilemmomas, acral keratosis, papillomatous papules or adult Lhermitte–Duclos disease (cerebellar gangliocytomas) | Macrocephaly (>97th percentile) | Mental retardation |

| 6 or more facial papules of which 3 or more trichilemmoma | Breast carcinoma (25–50 % of females) | Fibromas or lipomas; soft tissue tumors |

| Facial papules and oral mucosa papillomatosis | Thyroid carcinoma (3–10 %) | Thyroid hyperplastic nodules, and multiple adenomatous nodules |

| Oral mucosal papillomatosis and acral keratosis | Endometrial carcinoma (5–10 %) | Urogenital tumors, renal cell carcinoma |

| 6 or more acral keratoses | ||

| Two or more major criteria | ||

| One major or three or more minor criteria | ||

| Four or over four minor criteria | ||

| Adult Lhermitte–Duclos disease (cerebellar gangliocytomas) |

Pilarski et al. [5] have reviewed the criteria for Cowden syndrome and PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome and developed a revised, evidence-based criteria for diagnosis, including features of the broader spectrum of PTEN-related syndromes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Revised diagnostic criteria for PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome/Cowden syndrome [5]

| Major criteria |

| Breast cancer |

| Endometrial cancer (epithelial) |

| Thyroid cancer (follicular) |

| Gastrointestinal hamartomas (including ganglioneuromas, but excluding hyperplastic polyps; ≥ 3) Lhermitte–Duclos disease (adult) |

| Macrocephaly (≥97 percentile: 58 cm for females, 60 cm for males) |

| Macular pigmentation of the glans penis |

| Multiple mucocutaneous lesions (any of the following) |

| Multiple trichilemmomas (≥ 3, at least one biopsy proven) |

| Acral keratoses (≥3 palmoplantar keratotic pits and/or acral hyperkeratotic papules) |

| Mucocutaneous neuromas (≥3) |

| Oral papillomas (particularly on tongue and gingiva), multiple (≥ 3) OR biopsy proven OR dermatologist diagnosed |

| Minor criteria |

| Autism spectrum disorder |

| Colon cancer |

| Esophageal glycogenic acanthosis (≥3) |

| Lipomas (≥3) |

| Mental retardation (ie, IQ ≤ 75) |

| Renal cell carcinoma |

| Testicular lipomatosis |

| Thyroid cancer (papillary or follicular variant of papillary) |

| Thyroid structural lesions (eg, adenoma, multinodular goiter) |

| Vascular anomalies (including multiple intracranial developmental venous anomalies) |

| Operational diagnosis in an individual (either of the following) |

| Three or more major criteria, but one must include macrocephaly, Lhermitte–Duclos disease, or gastrointestinal hamartomas; or |

| Two major and three minor criteria |

| Operational diagnosis in a family where one individual meets revised PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome clinical diagnostic criteria or has a PTEN mutation |

| Any two major criteria with or without minor criteria; or |

| One major and two minor criteria; or |

| Three minor criteria |

From Pilarski et al. [5]

The major criteria include mucocutaneous lesions (trichilemmomas, multiple palmo-plantar keratoses, multifocal or extensive oral mucosal papillomatosis, multiple cutaneous facial pa-pules, and macular pigmentation of the glans penis), macrocephaly, nonmedullary thyroid cancer, breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and multiple gastrointestinal hamartomas or ganglioneuromas. Adult Lhermitte–Duclos disease (LDD), autism spectrum disorder with macrocephaly, and 2 biopsy-proven trichilemmomas are all pathognomonic for CS.

The minor criteria include mental retardation, autism spectrum disorder, fibrocystic disease of the breast, other thyroid lesions (multiple adenomatous nodules, adenomas, and multinodular hyperplasia), lipomas, fibromas, renal cell carci-noma, and uterine fibroids [8]. Pilarski et al. [5] found evidence to include autism spectrum disorders, colon cancer, renal cell carcinoma, penile macules, esophageal glycogenic acanthosis, testicular lipomatosis, and vascular anomalies to the list of criteria for diagnosis [5]. Upon review of the literature, these authors [5] found no evidence to support inclusion of benign breast diseases, uterine leiomyomas, or genitourinary malformations.

The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer is 85 %. The lifetime risk for thyroid follicular carcinoma and less often papillary thyroid carcinoma is approximately 35 %. The risk for endometrial cancer approaches 28 %, for kidney cancer the risk is about 33 %, for colorectal cancer about 9.0 % and for melanoma it is 6 %. Although breast, endometrial, and thyroid malignancies are the most frequent cancers in CS patients, patients with CS may be at increased risk for developing papillary renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and also glial tumors less frequently.

The great majority (almost 100 %) of affected CS individuals, by the third decade of life, develop the mucocutaneous stigmata lesions, as trichilemmomas, papillomatous papules, acral and plantar keratoses.

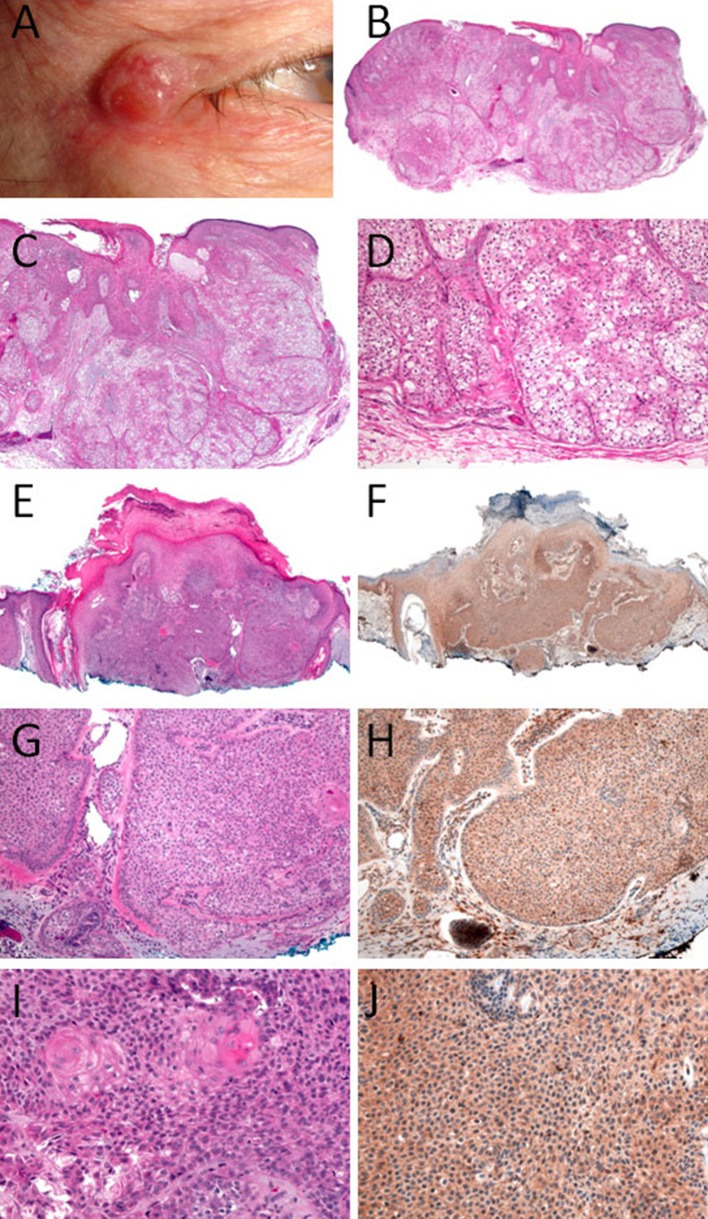

CS was originally felt to be mainly a dermatological disease until increased risks were ultimately shown for breast and other tumors. Facial lesions occur in the majority of patients. Multiple trichilemmomas are present in the central portion of the face, including the eyes, nose, mouth, and forehead. The most distinctive and peculiar facial features of CS consist of multiple small and keratotic papules concentrated around the orifices and are usually connected with hair follicles. A trichilemmoma is rarely a sporadic feature, and the literature regularly reports numerous lesions at presentation in individuals with a clinical and/or genetic diagnosis. Consequently, trichilemmoma is a clinically significant sign of CS when seen in multiplicity (at least ≥ 3), but at least one lesion should be biopsy-proven given the difficulty with clinical diagnosis. Descriptions of trichilemmomas as having either a papular or verruca-like external appearance, often leads to a mistaken clinical diagnosis of a facial wart. Furthermore, trichilemmomas are also clinically indistinguishable from other skin tumors, such as fibrofolliculomas, trichoepitheliomas, trichodiscomas, or other benign lesions involving the pilous and sebaceous units. There is a need to have confirmatory diagnosis by of trichilemmoma by histopathology [5] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Facial Trichilemmomas. a Clinical picture—33 year old male, right upper lateral eyelid lesion. b–d H&E of trichilemmomas of a 33 year old male, right upper lateral eyelid lesion. e, g, i H&E, and f, h, j PTEN IHC stain of trichilemmomas from a 50 year old male, right nasal ala lesion. This patient doe not have Cowden syndrome and the PTEN is maintained

Oral papillomas are a major criterion for diagnosis of CS. Oral papillomas are usually present in the lips and can be found also in the tongue, buccal mucosa, and gingivae [5, 9, 10]. Some authors have reported families with 100 % of patients developed oral papillomas by the second decade. However, diagnoses in these patients were characteristically based on dermatological features [11].

Other studies later confirmed this age of onset in both clinically diagnosed patients and PTEN mutation carriers. Oral papillomas are typically asymptomatic and thus can be distinguished from mucocutaneous neuromas in the same location. Nevertheless a biopsy of the mucosal lesion should be performed in clinically unclear lesions [2].

Hyperkeratotic and verrucous lesions and palmoplantar keratosis are commonly present on the dorsal surface of the hands and feet. Acral keratoses are located on the palmoplantar surfaces and dorsal hands/feet; these are hyperkeratotic wart-like appearing lesions [11]. Acral keratoses have been noted in both pediatric and adult populations of carriers of PTEN mutation. Rare cases were the observed keratoses diagnosed on nonacral sites, such as the face and trunk, but no confirmatory skin biopsy was mentioned. Further studies are needed to determine if keratoses are a common feature in non-acral sites in CS or PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome [5, 12].

Mucocutaneous neuromas (hamartoma of the peripheral nerve sheath) have been reported in the literature [5, 12]. Starink and colleagues reported that more than half of their patients that were diagnosed had developed mucocutaneous neuromas before age of 18 years [11]. Neuromas can also be observed on the face, the hands, palms, shins, and back. At least three mucocutaneous neuromas present on the face or elsewhere on the body, with or without a skin biopsy, should count as a major diagnostic feature of CS/PHTS according to the present findings.

Penile pigmentation is a major criterion in male subjects. Genital benign melanocytic neoplasms or melanosis are reported in up to 15 % of both male and female persons in the population. In the most recent literature, two large cohort studies reported that 48 % of all males with either a clinical diagnosis or a PTEN mutation and a combined 53 % of male PTEN mutation carriers were reported to have clinically significant penile freckling [13]. Based on the rise data, a patient with multiple genital lentigines seems to be especially predictive of PTEN mutation as compared with solitary genital brown macules.

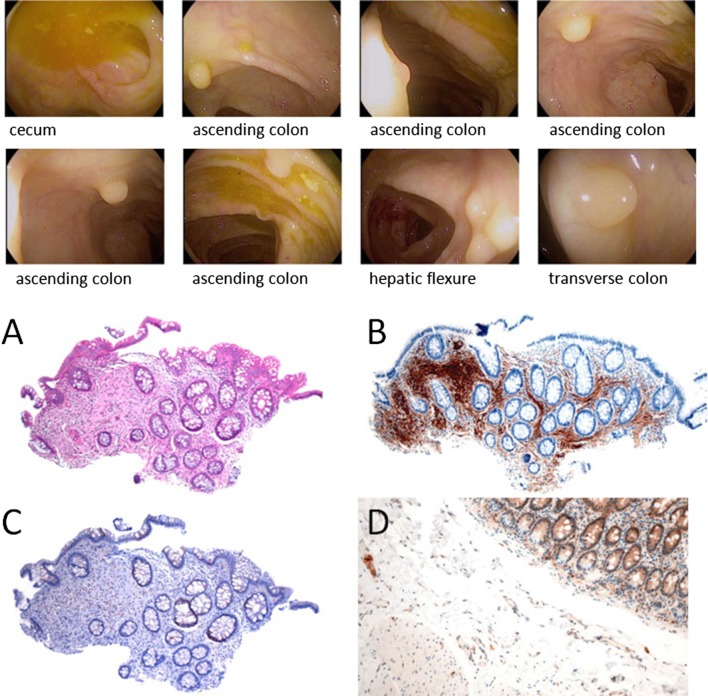

The gastrointestinal involvement in CS is represented by polyps of various histological types. These can be seen from the esophagus to the rectum, and their frequency is of the order of 60–80 % of all cases [14]. Gastrointestinal polyps in CS are hamartomatous; however, adenomatous and carcinomatous changes have also been reported in association with hamartomas [15, 16]. The high prevalence of adenomatous polyps has suggested that adenomas may be a manifestation of CS, rather than a coincidental finding as previously suggested. Besides the classical hamartomatous polyposis, diffuse esophageal acanthosis and ganglioneuromatosis are other findings associated with CS (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Patient with Cowden syndrome and numerous colonic polyps. Above: Endoscopy findings: 48 polyps found and removed. a H&E of one colonic polyp. b S100 immunostain from the same area. c PTEN immunostain from the same area. d PTEN (immunostain control for comparison)

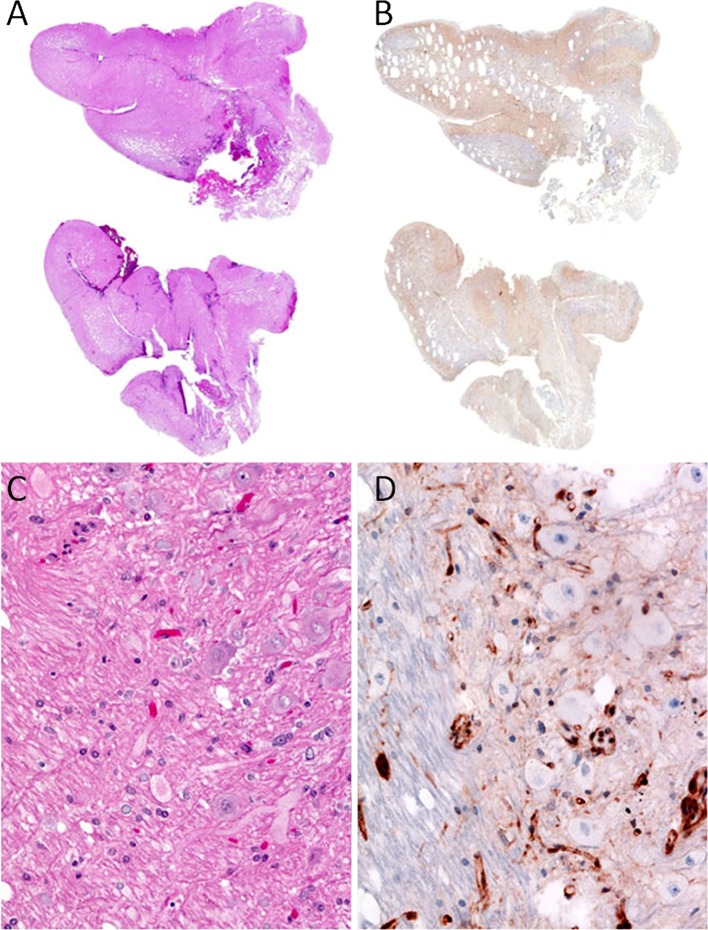

Thyroid pathologic findings in patients with PHTS that normally affect the follicular cells include multinodular goiter, multiple adenomatous nodules (MAN), follicular adenoma, follicular carcinoma, and less frequently papillary carcinoma [7]. Follicular carcinoma is an important feature in CS and BRRS. According to the diagnostic criteria for CS, follicular carcinoma is a major criterion, and multinodular goiter, adenomatous nodules, and follicular adenomas are minor criteria, with a frequency of 50–67 % [7, 17].

In a recent study evaluating thyroidectomy specimens from patients with CS and Bannayan-Riley Ruvalcaba syndrome [7], it was found that multiple adenomatous nodules were the most common finding (present in 75 %), followed by papillary thyroid carcinoma (60 %), lymphocytic thyroiditis (55 %), C-cell hyperplasia (55 %), follicular carcinomas (45 %), follicular adenomas (25 %), and nodular hyper-plasia (25 %) [7].

Multiple adenomatous nodules are characteristic findings in these syndromes and are present in 100 % of patients with CS [2, 15, 17]. They are present grossly as multiple firm yellow-tan well-circumscribed nodules. These nodules are multicentric, bilateral, well-circumscribed unencapsulated features similar to follicular adenomas (Fig. 3). The majority of carcinomas arise in a background of multiple adenomatous nodules [18]. The presence of multiple adenomatous nodules is followed by nodular hyperplasia and lymphocytic thyroiditis in 50 % of patients each, follicular adenomas present in about 38 % of patients, follicular carcinoma (25 %), and papillary thyroid carcinoma in 63 % of patients. The constellation of histologic findings in thyroidectomy specimens from CS is unusual, and although non-specific for CS, raises the possibility of a diagnosis of CS [7].

Fig. 3.

Multinodular thyroid with numerous adenomatous nodules in a 32 year old patient with Cowden syndrome PTEN immunostaining showing compete loss of immunoreactivity for PTEN of the follicular cells in one nodule. The endothelial cells and the adjacent thyroid follicular cells are positive

There were no morphologic differences between the thyroid findings in CS and BRRS. Although cancer risk in BRRS was expected to be similar to the general population, Laury et al. [7] found 4 cases of follicular thyroid carcinoma (67 %), showing that this type of carcinoma was more frequent in the pediatric population. Careful phenotyping gives further support for the suggestion that BRRS and CS are actually one condition, presenting at different stages [7]. Medullary thyroid carcinoma is not considered part of the spectrum of PHTS, however, earlier studies, including two studies by us [7, 18] have identified C-cell hyperplasia in individuals affected with this syndrome.

Newly described PTEN-related neoplasms include a distinctive soft tissue lesion highly associated with PHTS and termed PHOST (PTEN hamartoma of soft tissue). This lesion is an overgrowth of mingled soft tissue elements, mostly adipose and dense fibrous tissue, myxoid fibrous tissues, and abnormal blood vessels [19].

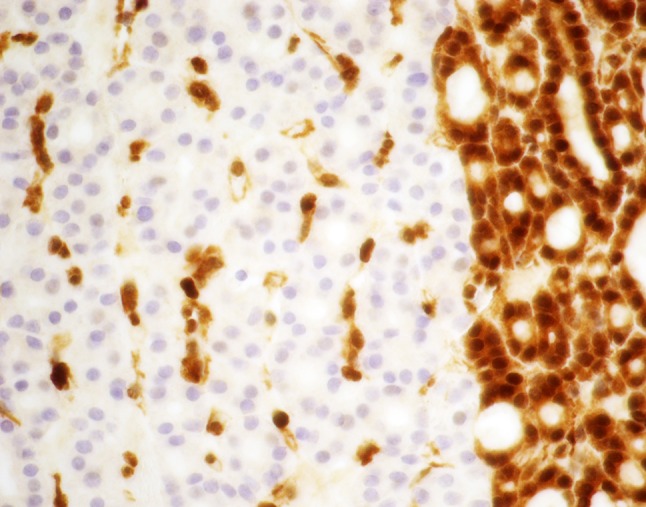

Adult Lhermitte–Duclos disease (LDD) with the diagnosis of dysplastic cerebellar gangliocytoma is pathognomonic for CS. Many of the ganglion cells in these lesions show loss of PTEN expression (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Dysplastic cerebellar gangliocytoma; patient with Lhermitte–Duclos. a, c H&E sections, b, c PTEN IHC immunostain. a Shows folial expansion of cerebellum, where the darkly staining granular cell layer is lost. c Shows the folial expansion corresponds to reduced PTEN expression by IHC. b Shows the granular cell layer being replaced by ganglion cells of varying sizes. d Shows many of the ganglion cells have lost PTEN expression. Note the retention of PTEN expression in background vasculature

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for the assessment of PTEN expression levels supply additional support to the diagnosis of CS.

PTEN IHC in trichilemmomas may be helpful in screening these tumors for association with CS. Scheper et al. [20] demonstrated the reduction or loss of PTEN expression in fibromas of the tongue in a patient with CS. Zabetian and Mehregan [21] described 2 patients with CS and multiple skin lesions. All lesions on these 2 patients had loss of expression of PTEN by IHC while the sporadic controls demonstrated normal PTEN immunoexpression. Al-Zaid et al. [22] have performed IHC for PTEN in six trichilemmomas from patients with CS and 33 biopsies from patients without CS and found complete loss of PTEN in 5/6 CS-associated lesions and 1/33 (3 %) of sporadic non-CS lesions. Jin et al. [23] have performed IHC stain in 102 cases of trichilemmomas in 95 patients; most of them were single lesion on the patient and none of their patients had the diagnosis of CS. They found that PTEN expression may be decreased in some sporadic tumors or associated lesions, as they found decreased expression in 6 cases of sporadic trichilemmomas. None of their cases had complete loss of PTEN [23]. Somatic PTEN loss is rare in sporadic trichilemmoma and demonstration of complete PTEN loss in trichilemmoma by IHC is strongly suggestive of association with CS. However, retention of PTEN staining does not exclude CS [2] (Fig. 1).

PTEN IHC staining of thyroidectomy specimens can aid in the recognition of patients with CS. In particular, the sensitivity and specificity of PTEN staining in thyroidectomy specimens for the detection of CS was found to be 100 and 92.3 %, respectively [24] (Fig. 3).

IHC for PTEN should be used in context with other major and minor defining clinical criteria, family history, genetic counseling, and possibly germline PTEN genotyping to confirm a diagnosis of CS. IHC staining for the assessment of PTEN expression levels provides additional support for the diagnosis of CS. Patients with negative PTEN IHC, patients with thyroid carcinomas, breast carcinoma, chromophobe and papillary renal cell carcinoma should be assessed to determine whether testing for CS or another hereditary syndrome is indicated [25].

Conclusion

The great majority of affected CS individuals develop the mucocutaneous stigmata lesions, as trichilemmomas, papillomatous papules, acral and plantar keratoses. Facial lesions occur in the majority of patients. The most typical and peculiar facial features of CS consist of multiple small and keratotic papules concentrated around the orifices and are associated with hair follicles. Immunohistochemical staining on these lesions showing loss of PTEN expression supports the diagnosis of CS. Germline PTEN genotyping confirms the diagnosis of CS.

A diagnosis of CS is important because it confers a significant risk for cancer. Early recognition of these skin lesions may help in an early diagnosis of the underlying malignancies that occur in CS patients and cancer screening and genetic counseling can be initiated.

References

- 1.Tan MH, Mester JL, Ngeow J, et al. Lifetime cancer risks in individuals with germline PTEN mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(2):400–407. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponti G, Pellacani G, Seidenari S, et al. Cancer-associated genodermatoses: skin neoplasms as clues to hereditary tumor syndromes. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;85(3):239–256. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonneau D, Longy M. Mutations of the human PTEN gene. Hum Mutat. 2000;16(2):109–122. doi: 10.1002/1098-1004(200008)16:2<109::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelen MR, Padberg GW, Peeters EA, et al. Localization of the gene for Cowden disease to chromosome 10q22-23. Nat Genet. 1996;13(1):114–116. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilarski R, Burt R, Kohlman W, et al. Cowden syndrome and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: systematic review and revised diagnostic criteria. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(21):1607–1616. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network I. The NCCN Guidelines Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. http://www.nccn.org.

- 7.Laury AR, Bongiovanni M, Tille JC, et al. Thyroid pathology in PTEN-hamartoma tumor syndrome: characteristic findings of a distinct entity. Thyroid. 2011;21(2):135–144. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biesecker LG, Happle R, Mulliken JB, et al. Proteus syndrome: diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and patient evaluation. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84(5):389–395. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19990611)84:5<389::AID-AJMG1>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starink TM, Hausman R. The cutaneous pathology of facial lesions in Cowden’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1984;11(5):331–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1984.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jornayvaz FR, Philippe J. Mucocutaneous papillomatous papules in Cowden’s syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33(2):151–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starink TM, van der Veen JP, Arwert F, et al. The Cowden syndrome: a clinical and genetic study in 21 patients. Clin Genet. 1986;29(3):222–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1986.tb00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferran M, Bussaglia E, Lazaro C, et al. Acral papular neuromatosis: an early manifestation of Cowden syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(1):174–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan MH, Mester J, Peterson C, et al. A clinical scoring system for selection of patients for PTEN mutation testing is proposed on the basis of a prospective study of 3042 probands. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haggitt RC, Reid BJ. Hereditary gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10(12):871–887. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198612000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanich PP, Owens VL, Sweetser S, et al. Colonic polyposis and neoplasia in Cowden syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(6):489–492. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marra GAF, Vecchio FM, Percesepe A, Anti M. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;16:1–6. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith JR, Marqusee E, Webb S, et al. Thyroid nodules and cancer in children with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):34–37. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zambrano E, Holm I, Glickman J, et al. Abnormal distribution and hyperplasia of thyroid C-cells in PTEN-associated tumor syndromes. Endocr Pathol. 2004;15(1):55–64. doi: 10.1385/EP:15:1:55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurek KC, Howard E, Tennant LB, et al. PTEN hamartoma of soft tissue: a distinctive lesion in PTEN syndromes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(5):671–687. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824dd86c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheper MA, Nikitakis NG, Sarlani E, et al. Cowden syndrome: report of a case with immunohistochemical analysis and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101(5):625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zabetian S, Mehregan D. Cowden syndrome: report of two cases with immunohistochemical analysis for PTEN expression. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34(6):632–634. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31824a22f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg JS, Prieto VG, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39(5):493–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2012.01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin M, Hampel H, Pilarski R, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homolog immunohistochemical staining and clinical criteria for Cowden syndrome in patients with trichilemmoma or associated lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35(6):637–640. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31827e28f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barletta JA, Bellizzi AM, Hornick JL. Immunohistochemical staining of thyroidectomy specimens for PTEN can aid in the identification of patients with Cowden syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(10):1505–1511. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31822fbc7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mester JL, Zhou M, Prescott N, et al. Papillary renal cell carcinoma is associated with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Urology. 2012;79(5):1187e1–1187e7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]